Quality of Life and Experience of Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Their Caregivers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

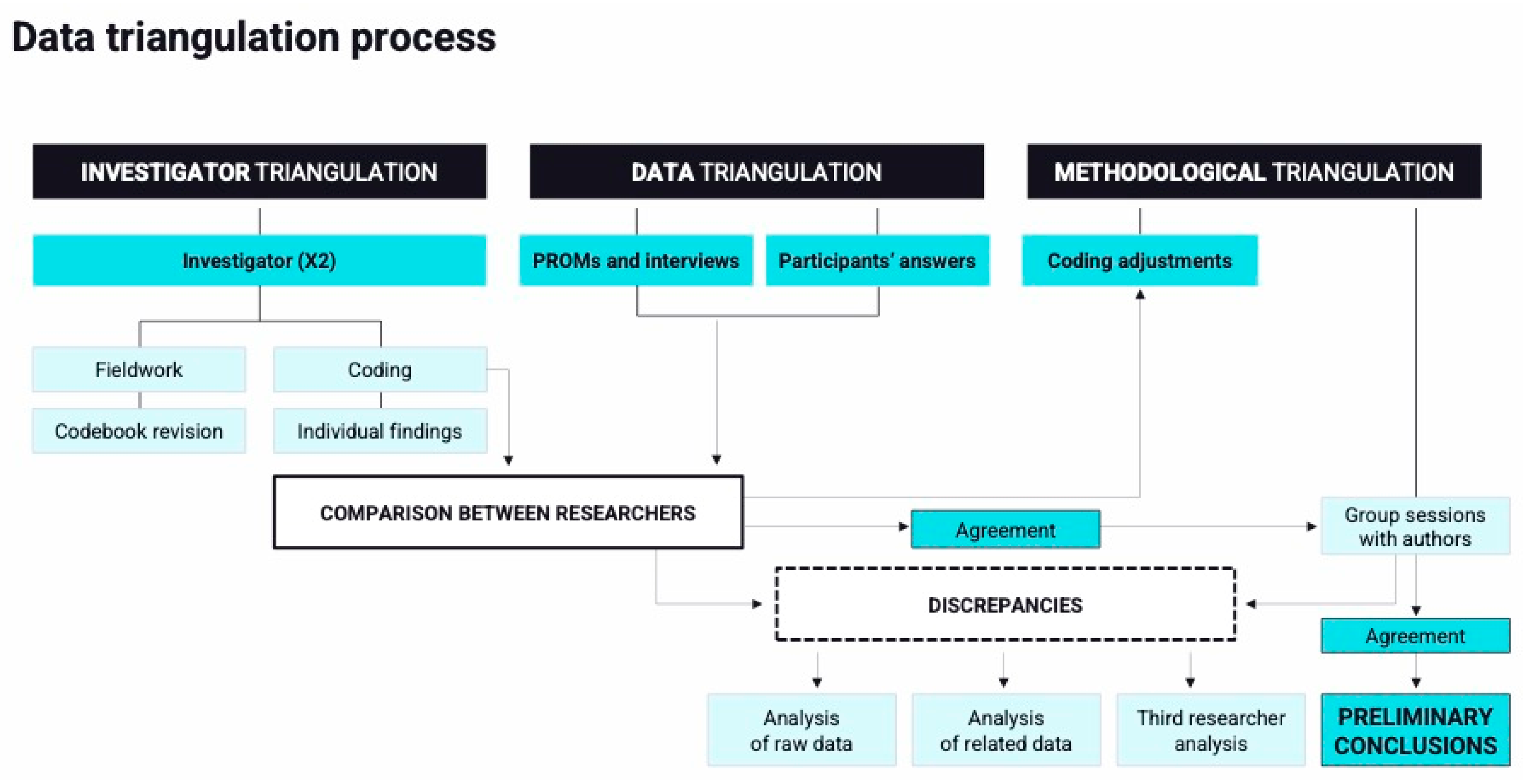

2.4.1. Qualitative

2.4.2. Mixed-Methods Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

3.2. Qualitative Findings

3.2.1. Theme 1: Impact of HF on QoL

- (a)

- Fear of physical/psychological decline/fast progression

- (b)

- Loss of agency

- (c)

- Sense of isolation

3.2.2. Theme 2: The New Role of Informal Caregiving

3.2.3. Theme 3: The Increasing Value of Multidisciplinary Care

- (a)

- New relationships with primary care (PC) physician

- (b)

- Provision of specialized support from HCPs

- (c)

- Provision of nursing care by a registered nurse

3.3. Descriptive Quantitative Data

| Thematic Domains | Sub-Themes | Verbatim Code | Nyha Class | Examples of Verbatim Quotations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain 1. The impact of HFpEF on QoL | ||||

| Fear of decline and progression | 101 | I | If I had to live my whole life with this, I’d feel really bad. I hope it gets better. | |

| 101 | I | Quality of life for me means being strong and taking good care of myself to help my family in whatever way I can, and my children and grandchildren. | ||

| 201 | II | Since I was admitted I feel that I have not gotten back on my feet. | ||

| 203 | II | He has to begin to accept that s/he is getting older, that he has hit a slump with the heart thing. That part is hard for him to accept. [Caregiver] | ||

| 303 | III | Today for example I feel fine, tomorrow I don’t know. There are days that I feel very low energy, without motivation. It’s not that I’m depressed, but just mad at myself because I’m not feeling well. There are days when I don’t do anything, I can’t go anywhere very far. I don’t even feel like reading because I get tired. | ||

| 304 | III | The night before an appointment with the doctor, I don’t sleep. I have been hospitalized so many times unexpectedly that I am always afraid to go, in case they see that I am not well and I have to be hospitalized. | ||

| 401 | IV | It has gotten worse and worse, now my daughters have sent me a lady to come and help me at home. For the past year I can no longer do things alone, neither get dressed nor clean myself. | ||

| Loss of agency | 103 | I | We used to travel a lot around the country and abroad, but now this limits us. If we go on vacation or on a daytrip, we do it around here. We get scared. We no longer want to be too far from the hospital. [Caregiver] | |

| 205 | II | Quality of life is being independent. Walking, being able to drink beer with my friends and do everyday things without getting tired. | ||

| 204 | II | If I’m walking down the street and I feel a little sick or short of breath, I put the wheelchair on the turbo setting and come home. | ||

| 305 | III | For me, quality of life it is being independent. I suffer because now I am not able to go to the supermarket, make my bed, prepare meals or clean the house. | ||

| 301 | III | How can I have any quality of life? My legs have been giving me a lot of trouble for several years now. I have rheumatism and osteoarthritis in my knees and it’s never going to get cured. No doctor has cured my osteoarthritis, and with my heart I can’t walk like I used to, or I have to walk slowly. | ||

| Sense of isolation | 0201 | III | Before COVID-19, even if I was already feeling unwell, I would go out, I would go to places, on Sundays I would go to the movies. Now with Covid, since we spent more than a year without being able to go out, I feel depressed. | |

| 306 | III | I miss having the independence to be able to meet and catch up with my friends. Now I ride an electric scooter, but I can’t spend much time away from home because I can’t get up from the scooter. | ||

| 303 | III | I have always been very social. Now I don’t see my friends because I can’t keep up when they meet up for a walk. | ||

| Domain 2. The new role of informal caregiving | ||||

| 203 | II | He no longer dares to go out alone, he always has to go with me. I have also learned how to give him the rescue medication and I am in charge of keeping track of the visits and phone calls with the hospital. [Caregiver] | ||

| 206 | II | I have a notebook in which every morning I write down her weight, meals, and medications. I always carry it with me during medical visits. [Caregiver] | ||

| 301 | III | My sisters and I have had to organize ourselves, and I have had to bring him/her food home, making sure s/he eats and that s/he eats well. Lately s/he doesn’t have an appetite, so I can tell how s/he is doing from the lunch boxes she leaves. [Caregiver] | ||

| 306 | III | It is difficult for me to have to depend on my wife. I have always been very independent and now I depend on my wife for everything, like washing or dressing. [Patient about her caregiver] | ||

| 401 | IV | She has already been admitted several times and I have learned to know when to call an ambulance. The last time I called because I noticed that my mother was moving as if she was in slow motion. I asked her to touch her nose with her hand, but she was asleep with her hand up, she didn’t have the strength to open her eyes. My mother never complains or says anything when they call her … So since I have telecare [remote care device], as soon as I see something strange, the first thing I do is press the button. When they arrived, she had arrhythmia and was taken to the hospital. At any rate, I am not a nurse and I am afraid that at some point something could go wrong. [Caregiver] | ||

| 401 | IV | I also have a house and a family, but I also have my mother. That’s why I had to appoint a caregiver who would go every day, otherwise I would have been overworked from Monday to Friday. [Caregiver] | ||

| Domain 3. The value of multidisciplinary care | ||||

| The new relationship with primary care | 101 | I | Partly due to the pandemic, when I phone my primary care physician, they rarely ever pick up. My heart problem was detected by the anesthesiologist who was getting me ready for a cataract operation. He saw something strange with the coagulation and referred me to the cardiologist at the hospital. If it were up to outpatient care, I’d still be waiting. | |

| 204 | II | With many of these health professionals, we have no communication. That’s why I have to say no to almost everything. The two of us are here to take care of each other, I take care of him and he takes care of me because we are both sick. [Caregiver] | ||

| 201 | II | I overwhelm my primary care physician, the poor thing. I start by telling her one thing and then another, and another, and another. I say that I overwhelm her because there are so many things. When it’s not for low blood sugar, then it’s for an embolism, a heart problem, a kidney problem or high blood pressure. I say that it is a lot for them to take on in the outpatient facility. | ||

| 201 | II | Neither my doctor nor the outpatient nurse know how to monitor my blood sugar. They tell me that I better monitor it myself because I know myself better than they do. Before, they gave me more guidance. They told me “have a little less, have a little more”. Since being admitted, not anymore. | ||

| 301 | III | When one has a disease, they usually seek out the cause in order to treat it. With my mother, the specialists do look into it more, but the primary care ones don’t look into it. They haven’t seen what causes everything that happens to my mother. [Caregiver] | ||

| 303 | III | The relationship with primary care has been really bad. When I call, I get music and then they hang up on me. I don’t feel like I can count on them if I get worse. | ||

| 401 | IV | Her family doctor isn’t really paying attention and doesn’t know about it. The ones closest to her are the paramedics and nurses who come to the house, who are more vigilant. But when I talk to her doctor and ask her about something that has happened, she never knows what’s going on. I get the impression that they don’t communicate with each other. [Caregiver] | ||

| Provision of clinical support from HCPs | 101 | I | During the first visit [in the cardiology unit] they explained to us that the fatigue could be due to several causes. So the first thing was to look at her medication and adjust it. The internal medicine specialist taught her how to take the thyroid medication that we knew she was taking incorrectly. The cardiologist did the ultrasound right then and there and explained to us about the deficiency, and the nurse told her how to weigh herself and measure her blood pressure. They told us that from then on they were going to take her directly from the hospital for a follow-up. This gave me a lot of peace of mind. [Caregiver] | |

| 204 | II | Now he is much more monitored than before because this team of cardiologists has taken her on and they have fine-tuned her treatment. We spent an hour with these doctors who visited with her, and I liked it and thought they treated her well. You don’t have to go from one specialist to another. They see everything that is heart-related. [Caregiver] | ||

| 202 | II | Both the cardiologist and the nurse talk to me a lot about what is going on with me and make recommendations about medication and diet. | ||

| 202 | II | They have treated me wonderfully, they even called me from the hospital to see how I am doing. | ||

| 304 | III | My doctor has a very serious personality, but she is wonderful, a very good person. It is very difficult for a transplant recipient to spend several years like this. I don’t see her as my doctor, I see her as a family member. | ||

| 302 | III | The primary care physician is very nice, but since they took me to cardiology, I haven’t seen him and I haven’t continued with him. Well, they are all nice, very attentive. The nurses too. I have no complaints. | ||

| 302 | III | I trust the doctor a lot, I ask him to please treat me as if I were his mother. | ||

| Provision of nursing care by a registered nurse | 201 | II | This week, the hospital nurses have already called several times. I feel that they care about me, they usually call every week to see how I am doing. | |

| 203 | II | The nurse always calls us. We have even done video calls from our house in the countryside, since I took him there in spring, and well, he had wonderful views sitting there at the door of his farmhouse, doing a video call with the nurse. I told him, you won’t have complaints about the care. [Caregiver] | ||

| NYHA I–II (n = 11) | NYHA III–IV (n = 9) | All NYHA (n = 20) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D-5L | |||

| EQ-ED-5L, patients reporting no problems, n (%) | |||

| Mobility | 4 (40%) | 0 | 4 (21%) |

| Self-care | 6 (60%) | 4 (44.4%) | 10 (53%) |

| Usual activities | 2 (20%) | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (16%) |

| Pain/discomfort | 6 (60%) | 0 | 6 (32%) |

| Anxiety/depression | 5 (50%) | 4 (44.4%) | 9 (47%) |

| EQ-ED-5L, patients reporting slight or moderate problems, n (%) | |||

| Mobility | 5 (50%) | 6 (66.6%) | 11 (58%) |

| Self-care | 3 (30%) | 3 (33.3%) | 6 (32%) |

| Usual activities | 7 (70%) | 4 (44.4%) | 11 (58%) |

| Pain/discomfort | 2 (20%) | 7 (77.8%) | 9 (47%) |

| Anxiety/depression | 5 (50%) | 3 (33.3%) | 8 (42%) |

| EQ-ED-5L, patients reporting severe or extreme problems, n (%) | |||

| Mobility | 1 (10%) | 3 (33.3%) | 4 (21%) |

| Self-care | 1 (10%) | 2 (22.2%) | 3 (16%) |

| Usual activities | 1 (10%) | 4 (44.4%) | 5 (26%) |

| Pain/discomfort | 2 (20%) | 2 (22.2%) | 4 (21%) |

| Anxiety/depression | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (11%) |

| EQ-ED-5L global, mean (SD) | |||

| Index value | 0.68 (0.26) | 0.34 (0.46) | 0.52 (0.40) |

| Quality of life visual analogue scale | 74 (13.56) | 51.6 (23.4) | 63.42 (23.05) |

| KCCQ, mean (SD) | |||

| Physical limitation | 62.42 (33.04) | 31.25 (29.28) | 47.65(33.04) |

| Symptom stability | 67.50 (23.72) | 52.78 (26.35) | 60.53 (25.43) |

| Symptom frequency | 73.96 (16.56) | 41.44 (28.29) | 58.55 (27.77) |

| Symptom burden | 71.67 (16.66) | 47.22 (23.94) | 60.09 (23.83) |

| Self-efficacy | 82.50 (24.44) | 86.11 (14.58) | 84.21 (19.91) |

| Quality of life | 59.17 (24.36) | 28.70 (29.50) | 44.74 (30.46) |

| Social limitation | 68.75(24.79) | 24.77 (34.68) | 47, 92 (36.75) |

| KCCQ, global scores, mean (SD) | |||

| Overall summary | 65.79 (21.59) | 32.26 (26.27) | 59.91 (28.90) |

| Clinical summary | 67.61 (22.13) | 37.79 (23.40) | 53.49 (26.88) |

| Total symptom | 72.81 (16.31) | 44.33 (25.11) | 59.32 (25.03) |

| PGIS, patient’s response, n (%) | |||

| No symptoms, very slightly, slightly | 7 (70%) | 5 (55.5%) | 12 (63%) |

| Moderate, intense, extreme | 3 (30%) | 4 (44.4%) | 7 (37%) |

| IEXPAC mean (SD) | |||

| Caregiver * | 5.38 (2.65) | 5.79 (2.55) * | 5.55 (2.54) |

| Conditional questions | 6.71 (2.25) | 6.25 (3.75) | 6.46 (2.99) |

| Patients | 6.75 (1.08) | 6.46 (1.80) | 6.61 (1.43) |

| Conditional questions | 7.97 (2.36) | 5.68 (2.36) | 6.60 (2.52) |

3.4. Complementarity and Discrepancies Between Qualitative and Quantitative Findings

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Metra, M.; Lund, L.H.; Milicic, D.; Costanzo, M.R.; Filippatos, G.; Gustafsson, F.; Tsui, S.; Barge-Caballero, E.; De Jonge, N.; et al. Advanced Heart Failure: A Position Statement of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 1505–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziaeian, B.; Fonarow, G.C. Epidemiology and Aetiology of Heart Failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré, N.; Vela, E.; Clèries, M.; Bustins, M.; Cainzos-Achirica, M.; Enjuanes, C.; Moliner, P.; Ruiz, S.; Verdú-Rotellar, J.M.; Comín-Colet, J. Medical Resource Use and Expenditure in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure: A Population-based Analysis of 88 195 Patients. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayago-Silva, I.; García-López, F.; Segovia-Cubero, J. Epidemiology of Heart Failure in Spain Over the Last 20 Years. Rev. Española Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2013, 66, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, R.; Palacios, B.; Varela, L.; Fernández, R.; Camargo Correa, S.; Estupiñan, M.F.; Calvo, E.; José, N.; Ruiz Muñoz, M.; Yun, S.; et al. Quality of Life and Disease Experience in Patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction in Spain: A Mixed-Methods Study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e053216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xin, Y.; Hu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Y. Quality of Life and Outcomes in Heart Failure Patients with Ejection Fractions in Different Ranges. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapelios, C.J.; Shahim, B.; Lund, L.H.; Savarese, G. Epidemiology, Clinical Characteristics and Cause-Specific Outcomes in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Card. Fail. Rev. 2023, 9, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-N.; Park, S.-M. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Insights from Recent Clinical Researches. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 514–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.; Fonarow, G.C.; Zile, M.R.; Lam, C.S.; Roessig, L.; Schelbert, E.B.; Shah, S.J.; Ahmed, A.; Bonow, R.O.; Cleland, J.G.F.; et al. Developing Therapies for Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2014, 2, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.-H.; Kraus, S.G.; Jowsey, T.; Glasgow, N.J. The Experience of Living with Chronic Heart Failure: A Narrative Review of Qualitative Studies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, R.; Glogowska, M.; McLachlan, S.; Cramer, H.; Sanders, T.; Johnson, R.; Kadam, U.; Lasserson, D.; Purdy, S. Unplanned Admissions and the Organisational Management of Heart Failure: A Multicentre Ethnographic, Qualitative Study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, R.E.; Jones, J.; Ho, P.M.; Bekelman, D.B. Caregivers’ Perceived Roles in Caring for Patients with Heart Failure: What Do Clinicians Need to Know? J. Card. Fail. 2014, 20, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, I.B. Linking Clinical Variables with Health-Related Quality of Life: A Conceptual Model of Patient Outcomes. JAMA 1995, 273, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comín-Colet, J.; Garin, O.; Lupón, J.; Manito, N.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Gómez-Bueno, M.; Ferrer, M.; Artigas, R.; Zapata, A.; Elosua, R. Validation of the Spanish Version of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire. Rev. Española Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2011, 64, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, J.J.; Nuño-Solinís, R.; Guilabert-Mora, M.; Solas-Gaspar, O.; Fernández-Cano, P.; González-Mestre, M.A.; Contel, J.C.; Del Río-Cámara, M. Development and Validation of an Instrument for Assessing Patient Experience of Chronic Illness Care. Int. J. Integr. Care 2016, 16, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigioni, F.; Carigi, S.; Grandi, S.; Potena, L.; Coccolo, F.; Bacchi-Reggiani, L.; Magnani, G.; Tossani, E.; Musuraca, A.C.; Magelli, C.; et al. Distance between Patients’ Subjective Perceptions and Objectively Evaluated Disease Severity in Chronic Heart Failure. Psychother. Psychosom. 2003, 72, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, S.; Lennie, T.A.; Okoli, C.; Moser, D.K. Quality of Life in Patients with Heart Failure: Ask the Patients. Heart Lung 2009, 38, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Aarons, G.A.; Horwitz, S.; Chamberlain, P.; Hurlburt, M.; Landsverk, J. Mixed Method Designs in Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2011, 38, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.C.; Caracelli, V.J.; Graham, W.F. Toward a Conceptual Framework for Mixed-Method Evaluation Designs. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1989, 11, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakdizaji, S.; Hassankhni, H.; Mohajjel Agdam, A.; Khajegodary, M.; Salehi, R. Effect of Educational Program on Quality of Life of Patients with Heart Failure: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Caring Sci. 2013, 2, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracso, D.; Bourrel, G.; Jorgensen, C.; Fanton, H.; Raat, H.; Pilotto, A.; Baker, G.; Pisano, M.M.; Ferreira, R.; Valsecchi, V.; et al. The Chronic Disease Self-Management Programme: A Phenomenological Study for Empowering Vulnerable Patients with Chronic Diseases Included in the EFFICHRONIC Project. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcimartín, P.; Astals-Vizcaino, M.; Badosa, N.; Linas, A.; Ivern, C.; Duran, X.; Comín-Colet, J. The Impact of Motivational Interviewing on Self-Care and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2022, 37, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample Sizes for Saturation in Qualitative Research: A Systematic Review of Empirical Tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Saturation in qualitative research. In SAGE Research Methods Foundations; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M. A Simple Method to Assess and Report Thematic Saturation in Qualitative Research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.G.; Fischhoff, B.; Bostrom, A.; Atman, C.J. Risk Communication: A Mental Models Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Coats, A.J.; Tsutsui, H.; Abdelhamid, M.; Adamopoulos, S.; Albert, N.; Anker, S.D.; Atherton, J.; Böhm, M.; Butler, J.; et al. Universal Definition and Classification of Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2021, 27, 387–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universal Definition and Classification of Heart Failure: A Step in the Right Direction from Failure to Function. American College of Cardiology. Available online: https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2021/07/12/12/31/http%3a%2f%2fwww.acc.org%2fLatest-in-Cardiology%2fArticles%2f2021%2f07%2f12%2f12%2f31%2fUniversal-Definition-and-Classification-of-Heart-Failure (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tuomilehto, J.; Jousilahti, P.; Antikainen, R.; Mähönen, M.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Hu, G. Lifestyle Factors in Relation to Heart Failure Among Finnish Men and Women. Circ. Heart Fail. 2011, 4, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Wal, M.H.L.; Jaarsma, T.; Van Veldhuisen, D.J. Non-compliance in Patients with Heart Failure; How Can We Manage It? Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2005, 7, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Goñi, J.M.; Craig, B.M.; Oppe, M.; Ramallo-Fariña, Y.; Pinto-Prades, J.L.; Luo, N.; Rivero-Arias, O. Handling Data Quality Issues to Estimate the Spanish EQ-5D-5L Value Set Using a Hybrid Interval Regression Approach. Value Health 2018, 21, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viktrup, L.; Hayes, R.P.; Wang, P.; Shen, W. Construct Validation of Patient Global Impression of Severity (PGI-S) and Improvement (PGI-I) Questionnaires in the Treatment of Men with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Secondary to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. BMC Urol. 2012, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilabert, M.; Amil, P.; González-Mestre, A.; Gil-Sánchez, E.; Vila, A.; Contel, J.; Ansotegui, J.; Solas, O.; Bacigalupe, M.; Fernández-Cano, P.; et al. The Measure of the Family Caregivers’ Experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EQ-5D-5L. EuroQol. Available online: https://euroqol.org/information-and-support/euroqol-instruments/eq-5d-5l/ (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Kuan, W.C.; Chee, K.H.; Kasim, S.; Lim, K.K.; Dujaili, J.A.; Lee, K.K.-C.; Teoh, S.L. Validity and Measurement Equivalence of EQ-5D-5L Questionnaire Among Heart Failure Patients in Malaysia: A Cohort Study. J. Med. Econ. 2024, 27, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boczor, S.; Eisele, M.; Rakebrandt, A.; Menzel, A.; Blozik, E.; Träder, J.-M.; Störk, S.; Herrmann-Lingen, C.; Scherer, M.; for the RECODE-HF Study Group; et al. Prognostic Factors Associated with Quality of Life in Heart Failure Patients Considering the Use of the Generic EQ-5D-5LTM in Primary Care: New Follow-up Results of the Observational RECODE-HF Study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, C.P.; Porter, C.B.; Bresnahan, D.R.; Spertus, J.A. Development and Evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: A New Health Status Measure for Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 35, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, Y.; Khariton, Y.; Tang, Y.; Nassif, M.E.; Chan, P.S.; Arnold, S.V.; Jones, P.G.; Spertus, J.A. Association of Serial Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Assessments with Death and Hospitalization in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 1315–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassif, M.; Fine, J.T.; Dolan, C.; Reaney, M.; Addepalli, P.; Allen, V.D.; Sehnert, A.J.; Gosch, K.; Spertus, J.A. Validation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in Symptomatic Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. JACC Heart Fail. 2022, 10, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magouliotis, D.E.; Bareka, M.; Rad, A.A.; Christodoulidis, G.; Athanasiou, T. Demystifying the Value of Minimal Clinically Important Difference in the Cardiothoracic Surgery Context. Life 2023, 13, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinera Elorriaga, K.; Arteagoitia González, M.; González Llinares, R.; Lamiquiz Linares, E. IEXPAC, a Tool to Assess Patient Experience. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafl, K.A. Patton, M.Q. (1990). Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 532 pp., $28.00 (Hardcover). Res. Nurs. Health 1991, 14, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.; Bryant-Lukosius, D.; DiCenso, A.; Blythe, J.; Neville, A.J. The Use of Triangulation in Qualitative Research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHorney, C.A.; Mansukhani, S.G.; Anatchkova, M.; Taylor, N.; Wirtz, H.S.; Abbasi, S.; Battle, L.; Desai, N.R.; Globe, G. The Impact of Heart Failure on Patients and Caregivers: A Qualitative Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J.S.; Graven, L.J. Problems Experienced by Informal Caregivers of Individuals with Heart Failure: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 80, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell-Davies, F.; Goyder, C.; Gale, N.; Hobbs, F.D.R.; Taylor, C.J. The Role of Informal Carers in the Diagnostic Process of Heart Failure: A Secondary Qualitative Analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2019, 19, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoz, R.; Proudfoot, C.; Fonseca, A.F.; Loefroth, E.; Corda, S.; Jackson, J.; Cotton, S.; Studer, R. Caregivers of Patients with Heart Failure: Burden and the Determinants of Health-Related Quality of Life. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2021, 15, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, W.W.; Kitko, L.A.; Hupcey, J.E. Intergenerational Caregivers of Parents with End-Stage Heart Failure. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2018, 32, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, S.A.; Grigsby, M.E.; Riegel, B.; Bekelman, D.B. The Impact of Relationship Quality on Health-Related Outcomes in Heart Failure Patients and Informal Family Caregivers: An Integrative Review. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2015, 30, S52–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusdal, A.K.; Josefsson, K.; Adolfsson, E.T.; Martin, L. Informal Caregivers’ Experiences and Needs When Caring for a Relative with Heart Failure: An Interview Study. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 31, E1–E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirta, S.B.; Balas, B.; Proenca, C.C.; Bailey, H.; Phillips, Z.; Jackson, J.; Cotton, S. Perceptions of Heart Failure Symptoms, Disease Severity, Treatment Decision-Making and Side Effects by Patients and Cardiologists: A Multinational Survey in a Cardiology Setting. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2018, 14, 2265–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, K.M.; Bixby, M.B.; Naylor, M.D. Advanced Practice Nurse Strategies to Improve Outcomes and Reduce Cost in Elders with Heart Failure. Dis. Manag. 2006, 9, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordóñez-Piedra, J.; Ponce-Blandón, J.A.; Robles-Romero, J.M.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Jiménez-Picón, N.; Romero-Martín, M. Effectiveness of the Advanced Practice Nursing Interventions in the Patient with Heart Failure: A Systematic Review. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 1879–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comín-Colet, J.; Verdú-Rotellar, J.M.; Vela, E.; Clèries, M.; Bustins, M.; Mendoza, L.; Badosa, N.; Cladellas, M.; Ferré, S.; Bruguera, J. Efficacy of an Integrated Hospital-Primary Care Program for Heart Failure: A Population-Based Analysis of 56 742 Patients. Rev. Española Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2014, 67, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raat, W.; Smeets, M.; Janssens, S.; Vaes, B. Impact of Primary Care Involvement and Setting on Multidisciplinary Heart Failure Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 802–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, V.U.; Bhasin, A.; Vargas, J.; Arun Kumar, V. A Multidisciplinary Approach to Heart Failure Care in the Hospital: Improving the Patient Journey. Hosp. Pract. 2022, 50, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maryniak, A.; Maisuradze, N.; Ahmed, R.; Biskupski, P.; Jayaraj, J.; Budzikowski, A.S. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Update: A Review of Clinical Trials and New Therapeutic Considerations. Cardiol. J. 2022, 29, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahhan, A.S.; Vaduganathan, M.; Kumar, S.; Okafor, M.; Greene, S.J.; Butler, J. Design Elements and Enrollment Patterns of Contemporary Trials in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Systematic Review. JACC Heart Fail. 2018, 6, 714–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.; Olazo, K.; Sierra, M.; Tarver, M.E.; Caldwell, B.; Saha, A.; Lisker, S.; Lyles, C.; Sarkar, U. Do Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Measure up? A Qualitative Study to Examine Perceptions and Experiences with Heart Failure Proms among Diverse, Low-Income Patients. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2022, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwaltney, C.; Pro, S.; Slagle, A.; Martin, M.L.; Ariely, R.; Brede, Y. Hearing the Voice of the Heart Failure Patient: Key Experiences Identified in Qualitative Interviews. Br. J. Cardiol. 2012, 19, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants (n = 19) | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 80 (7) | |

| Range (minimum–maximum) | 67–92 | |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 8 | 42 |

| Time since diagnosis, years, mean (SD) | 3.3 (5.7) | |

| Recent diagnosis (less than 2 months), n (%) | 2 | 10 |

| NYHA classification, n (%) | ||

| I | 4 | 21 |

| II | 6 | 32 |

| III | 7 | 37 |

| IV | 2 | 10 |

| LVEF, mean (SD) | 64 (7.3) | |

| Range (minimum–maximum) | 50–78 |

| Verbatim Code | NYHA | Age | Gender | Educational Level | Marital Status | Main Caregiver | Number of Cohabitants * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101 | I | 80 | Female | Elementary | Widow | Daughter | 0 |

| 103 | I | 76 | Male | Elementary | Married | Wife | 1 |

| 104 | I | 80 | Male | University | Married | Wife | 2 |

| 105 | I | 71 | Female | Elementary | Married | Husband | 2 |

| 201 | II | 67 | Female | Elementary | Married | Husband | 1 |

| 202 | II | 86 | Male | Elementary | Married | Wife | 1 |

| 203 | II | 86 | Male | Elementary | Married | Wife | 2 |

| 204 | II | 77 | Male | Elementary | Married | Wife | 1 |

| 205 | II | 67 | Male | Elementary | Married | Wife | 1 |

| 206 | II | 92 | Female | Elementary | Widow | Daughter | 1 |

| 301 | III | 88 | Male | Elementary | Widow | Daughter | 0 |

| 302 | III | 82 | Female | Elementary | Widow | Son | 1 |

| 303 | III | 82 | Female | Elementary | Single | Niece | 0 |

| 304 | III | 72 | Female | Elementary | Single | Brother | 0 |

| 305 | III | 85 | Female | Elementary | Widow | Daughter | 0 |

| 306 | III | 77 | Male | Elementary | Married | Wife | 1 |

| 307 | III | 87 | Female | Elementary | Widow | Son | 1 |

| 401 | IV | 83 | Female | Elementary | Widow | Daughter | 1 |

| 402 | IV | 85 | Female | University | Widow | Son | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rubio, R.; Palacios, B.; Varela, L.; Gutiérrez Ibañez, M.; Camargo Correa, S.; Calvo Barriuso, E.; José, N.; Yun Viladomat, S.; Soria Gómez, M.T.; Montero Hernández, E.; et al. Quality of Life and Experience of Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Their Caregivers. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4715. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134715

Rubio R, Palacios B, Varela L, Gutiérrez Ibañez M, Camargo Correa S, Calvo Barriuso E, José N, Yun Viladomat S, Soria Gómez MT, Montero Hernández E, et al. Quality of Life and Experience of Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Their Caregivers. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(13):4715. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134715

Chicago/Turabian StyleRubio, Raül, Beatriz Palacios, Luis Varela, Martín Gutiérrez Ibañez, Selene Camargo Correa, Elena Calvo Barriuso, Nuria José, Sergi Yun Viladomat, María Teresa Soria Gómez, Esther Montero Hernández, and et al. 2025. "Quality of Life and Experience of Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Their Caregivers" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 13: 4715. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134715

APA StyleRubio, R., Palacios, B., Varela, L., Gutiérrez Ibañez, M., Camargo Correa, S., Calvo Barriuso, E., José, N., Yun Viladomat, S., Soria Gómez, M. T., Montero Hernández, E., Hidalgo, E., Enjuanes, C., Rueda, Y., San Saturnino, M., Garcimartín, P., López-Ibor, J. V., Segovia-Cubero, J., & ComínColet, J. (2025). Quality of Life and Experience of Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Their Caregivers. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(13), 4715. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134715