Greek Version of the Distress Thermometer for Parents of Children with Dysphagia: A Validation Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instrument

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Psychometric Characteristics of the DT-P

3.2.1. Internal Consistency and Validity

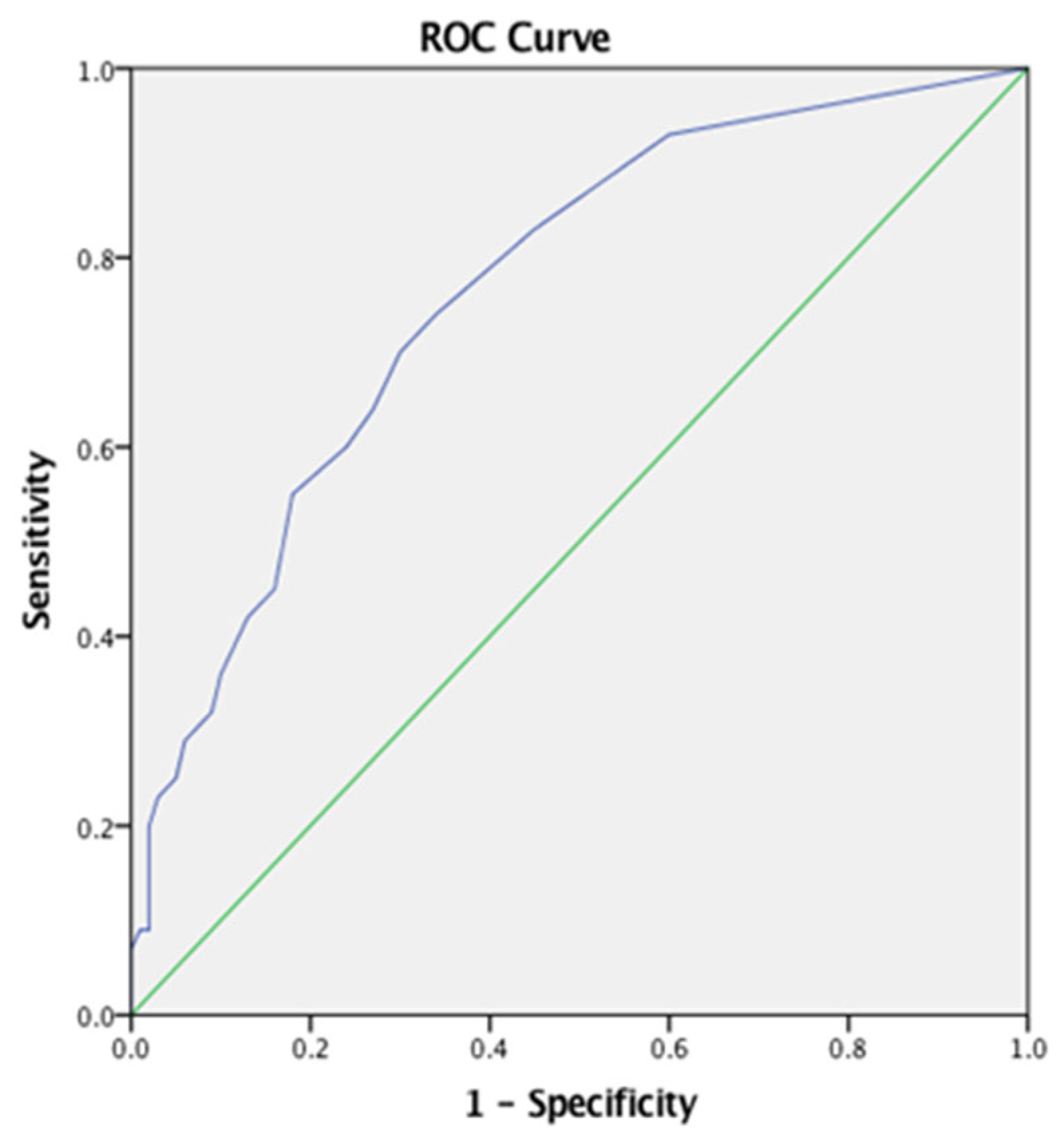

3.2.2. Sensitivity and Specificity

3.2.3. Comparison of Means Between Groups

3.2.4. Construct Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Strengths

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yach, D.; Hawkes, C.; Gould, C.L.; Hofman, K.J. The global burden of chronic diseases: Overcoming impediments to prevention and control. JAMA 2004, 291, 2616–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yach, D.; Beaglehole, R. Globalization of risks for chronic diseases demands global solutions. Perspect. Glob. Dev. Technol. 2004, 3, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaire, P. Disease, illness and health: Theoretical models of the disablement process. Bull. World Health Organ. 1992, 70, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Van Der Lee, J.H.; Mokkink, L.B.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Heymans, H.S.; Offringa, M. Definitions and measurement of chronic health conditions in childhood: A systematic review. JAMA 2007, 297, 2741–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowrick, C.; Dixon-Woods, M.; Holman, H.; Weinman, J. What is chronic illness? Chronic Illn. 2005, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, J.B.; Fernández, C.S.; de Oliveira, M.B.; Lagos, C.M.; Martínez, M.T.; Hernández, C.L.; del Cura González, I. Chronic diseases in the paediatric population: Comorbidities and use of primary care services. An. Pediatr. (Engl. Ed.) 2020, 93, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oers, H.A.; Schepers, S.A.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Haverman, L. Dutch normative data and psychometric properties for the Distress Thermometer for Parents. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablotsky, B.; Black, L.I.; Maenner, M.J.; Schieve, L.A.; Danielson, M.L.; Bitsko, R.H.; Blumberg, S.J.; Kogan, M.D.; Boyle, C.A. Prevalence and trends of developmental disabilities among children in the United States: 2009–2017. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20190811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beacham, B.L.; Deatrick, J.A. Children with chronic conditions: Perspectives on condition management. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015, 30, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfon, N.; Newacheck, P.W. Evolving notions of childhood chronic illness. JAMA 2010, 303, 665–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesey, S. Dysphagia and quality of life. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2013, 18, S14–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourin, P.F.; Puech, M.; Woisard, V. Pediatric aspect of dysphagia. In Dysphagia: Diagnosis and Treatment; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, C.M.; Choi, S. Diagnosis and management of pediatric dysphagia: A review. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 146, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.; Pitceathly, R.D.; Rose, M.R.; McGowan, S.; Hill, M.; Badrising, U.A.; Hughes, T. Interventions for dysphagia in long-term, progressive muscle disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD004303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, L.; Battles, H.; Zadeh, S.; Widemann, B.C.; Pao, M. Validity, specificity, feasibility, and acceptability of a brief pediatric distress thermometer in outpatient clinics. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, J.; Atwood, C.; Gnagi, S.; Teufel, R.; Clemmens, C. Temporal trends of pediatric dysphagia in hospitalized patients. Dysphagia 2018, 33, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.J. The neurobiology of swallowing and dysphagia. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2008, 14, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platis, C.; Papagianni, A.; Stergiannis, P.; Messaropoulos, P.; Intas, G. Attitudes of the general population regarding patient information for a chronic and life-threatening disease: A cross-sectional study. In GeNeDis 2020: Geriatrics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvedson, J.C. Assessment of pediatric dysphagia and feeding disorders: Clinical and instrumental approaches. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2008, 14, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goday, P.S.; Huh, S.Y.; Silverman, A.; Lukens, C.T.; Dodrill, P.; Cohen, S.S.; Delaney, A.L.; Feuling, M.B.; Noel, R.J.; Gisel, E.; et al. Pediatric feeding disorder: Consensus definition and conceptual framework. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 68, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy Salem, S.; Graham, R.J. Chronic illness in pediatric critical care. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 686206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.L.; McIntyre, L.L.; Blacher, J.; Crnic, K.; Edelbrock, C.; Low, C. Pre-school children with and without developmental delay: Behaviour problems and parenting stress over time. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2003, 47, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, J.; Caravale, B.; Marcelli, M.; Franco, F.; Colver, A. Parenting stress and children with cerebral palsy: A European cross-sectional survey. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2011, 53, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, N.; Neece, C.L. Parenting stress and emotion dysregulation among children with developmental delays: The role of parenting behaviors. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 4071–4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, M.; Palikara, O.; Van Herwegen, J. Comparing parental stress of children with neurodevelopmental disorders: The case of Williams syndrome, Down syndrome and autism spectrum disorders. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 32, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, A.; Siafaka, V.; Tsapara, A.; Tafiadis, D.; Kotsis, K.; Skapinakis, P.; Tzoufi, M. Measuring parental stress, illness perceptions, coping and quality of life in families of children newly diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. BJPsych Open 2023, 9, e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, A.; Fouska, S.; Tafiadis, D.; Trimmis, N.; Plotas, P.; Siafaka, V. Psychometric properties of the Greek version of the Autism Parenting Stress Index (APSI) among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, N.O.; Carter, A.S. Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2008, 38, 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, A.; Olson, E.; Sullivan, K.; Greenson, J.; Winter, J.; Dawson, G.; Munson, J. Parenting-related stress and psychological distress in mothers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Dev. 2013, 35, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Yen, H.C.; Tseng, M.H.; Tung, L.C.; Chen, Y.D.; Chen, K.L. Impacts of autistic behaviors, emotional and behavioral problems on parenting stress in caregivers of children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovagnoli, G.; Postorino, V.; Fatta, L.M.; Sanges, V.; De Peppo, L.; Vassena, L.; De Rose, P.; Vicari, S.; Mazzone, L. Behavioral and emotional profile and parental stress in preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 45, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, P.; Ding, Y.; Chen, E.C.; Cho, S.J.; Wang, C.; Hwang, J. Parenting styles, parenting stress, and behavioral outcomes in children with autism. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2021, 42, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Tuinman, M.A.; Gazendam-Donofrio, S.M.; Hoekstra-Weebers, J.E. Screening and referral for psychosocial distress in oncologic practice: Use of the Distress Thermometer. Cancer 2008, 113, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abidin, R.; Flens, J.R.; Austin, W.G. The Parenting Stress Index; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 297–328. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.O.; Jones, W.H. Parental Stress Scale (PSS); American Psychological Association (APA): Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittingham, K.; Wee, D.; Sanders, M.R.; Boyd, R. Predictors of psychological adjustment, experienced parenting burden and chronic sorrow symptoms in parents of children with cerebral palsy. Child Care Health Dev. 2013, 39, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, B.C. Validation of a caregiver strain index. J. Gerontol. 1983, 38, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varni, J.W.; Seid, M.; Kurtin, P.S. PedsQL™ 4.0: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Version 4.0 Generic Core Scales in healthy and patient populations. Med. Care 2001, 39, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varni, J.W.; Burwinkle, T.M.; Seid, M. The PedsQL TM 4.0 as a school population health measure: Feasibility, reliability, and validity. Qual. Life Res. 2006, 15, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E., Jr.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, G.R.; Neto, J.F.; de Camargo, S.M.; Lucchetti, A.L.G.; Espinha, D.C.M.; Lucchetti, G. Caregiving across the lifespan: Comparing caregiver burden, mental health, and quality of life. Psychogeriatrics 2015, 15, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Courten, M.; de Courten, B.; Egger, G.; Sagner, M. The epidemiology of chronic disease. In Lifestyle Medicine; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCubbin, M.A.; Huang, S.T. Family strengths in the care of handicapped children: Targets for intervention. Fam. Relat. 1989, 38, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverman, L.; van Oers, H.A.; Limperg, P.F.; Houtzager, B.A.; Huisman, J.; Darlington, A.S.; Maurice-Stam, H.; Grootenhuis, M.A. Development and validation of the distress thermometer for parents of a chronically ill child. J. Pediatr. 2013, 163, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaleontiou, A.; Siafaka, V.; Voniati, L.; Georgiou, R.; Tafiadis, D. Psychometric Properties of the “Distress Thermometer for Parents (DT-P)” Questionnaire in Greek-Cypriot Parents: A Pilot Study. Poster Presented at the 8th Congress on Neurobiology, Psychopharmacology & Treatment Guidance, Thessaloniki, Greece, 17–19 February 2023. Available online: https://psychiatry.gr/8icnpepatg/images/final.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0. Armonk, NY. IBM Corp; 2023. The jamovi Project (2023). jamovi (Version 2.4) [Computer Software]. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Kyranou, M.; Varvara, C.; Papathanasiou, M.; Diakogiannis, I.; Zafeiropoulos, K.; Apostolidis, M.; Papandreou, C.; Syngelakis, M. Validation of the Greek version of the distress thermometer compared to the clinical interview for depression. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, F.J.; Hashem, Z.; Stegmann, R.; Aoun, S.M. The support needs of parent caregivers of children with a life-limiting illness and approaches used to meet their needs: A scoping review. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, C.B.; Dehnadi, M.; Snow, M.E.; Clark, N.; Lui, M.; McLean, J.; Mamdani, H.; Kooijman, A.L.; Bubber, V.; Hoefer, T.; et al. Themes for evaluating the quality of initiatives to engage patients and family caregivers in decision-making in healthcare systems: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e050208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, K.D.; Jones, B.L. Supporting parent caregivers of children with life-limiting illness. Children 2018, 5, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, J.; Wolfe, K.; Hock, R.; Scopano, L. Advances in supporting parents in interventions for autism spectrum disorder. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 69, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Group (n = 100) | Control Group (n = 100) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Children’s Age (years) | 7.60 (4.25–10.90) | 6.85 (4.25–9.40) | 0.407 + |

| Parents’ Age (years) | |||

| Maternal Age | 39.00 (35.00–42.00) | 37.00 (35.00–41.50) | 0.498 + |

| Paternal Age | 41.00 (36.00–46.00) | 40.00 (37.00–43.00) | 0.980 + |

| Parents’ Gender, N (%) | |||

| Male | 25 (25.0%) | 13 (13.0%) | 0.498 ++ |

| Female | 75 (75.0%) | 87 (87.0%) | 0.980 ++ |

| Children’s Gender, N (%) | |||

| Male | 72 (72.0%) | 56 (56.0%) | |

| Female | 28 (28.0%) | 44 (44.0%) |

| Medical Group N (%) | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Acquired Disorders N = 8 (8%) | Cerebellar Atrophy (N = 5), Left Side Lobotomy (N = 1), Medial Agenesis (N = 1), PKU (N = 1), |

| Developmental Disorders N = 44 (44%) | ASD (N = 40), SLI (N = 2), Neurodevelopmental Disorder (N = 2), |

| Genetic Syndromes N = 15 (15%) | Fragile X Syndrome (N = 2), Coffin-Siris Syndrome (N = 1) DiGeorge Syndrome(N = 1), Down Syndrome (N = 5), Dandy-Walker Syndrome (N = 1), Mowat Wilson Syndrome (N = 1), Rett Syndrome (N = 2), 1q44 Syndrome (N = 1), ArCapa Syndrome (N = 1) |

| Cerebral Palsy Ν = 15 (15%) | Cerebral Palsy (N = 15) |

| Other Medical Conditions N = 18 (18%) | Hard of Hearing (N = 1), Severe delays in Development (N = 17) |

| Feeding/Swallowing Disorder, N (100%) | Oral Sensory Feeding Disorder 41 (41%) Oral Motor Feeding Disorder 43 (43%) Oropharyngeal Dysphagia 16 (16%) |

| DT-P | n | M | S.D. | Cronbach’s α | No. of Items | Possible Scores | Observed Scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Min | Max | ||||||

| Thermometer score (overall distress) | 200 | 3.67 | 2.89 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | ||

| Practical problems | 200 | 1.79 | 2.12 | 0.827 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Family/social problems | 200 | 0.49 | 0.92 | 0.676 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Emotional problems | 200 | 2.03 | 2.28 | 0.820 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 8 |

| Physical problems | 200 | 1.84 | 2.05 | 0.825 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Cognitive problems | 200 | 0.54 | 0.77 | 0.674 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Parenting ≥ 2 years old child | 188 | 0.97 | 1.46 | 0.805 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Parenting < 2 years old child | 12 | 1.67 | 2.15 | 0.880 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Total score (5 domains) | 200 | 6.68 | 6.78 | 0.928 | 29 | 0 | 29 | 0 | 27 |

| Total score ≥ 2 y (6 domains) | 188 | 7.70 | 7.70 | 0.934 | 34 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 31 |

| Total score < 2 y (6 domains) | 12 | 7.50 | 7.82 | 0.936 | 35 | 0 | 35 | 0 | 25 |

| Enough support (yes) | 200 | 192 | 96.0% | ||||||

| Wish for referral (yes/maybe) | 200 | 57 | 28.5% | ||||||

| Clinical | Typical | t | df | p-Value | Eta | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | S.D. | n | Mean | S.D. | |||||

| Practical problems | 100 | 2.74 | 2.28 | 100 | 0.83 | 1.43 | 7.11 | 166.50 | <0.001 | 0.203 |

| Emotional problems | 100 | 2.88 | 2.46 | 100 | 1.18 | 1.71 | 5.67 | 176.33 | <0.001 | 0.140 |

| Family/social problems | 100 | 0.82 | 1.13 | 100 | 0.15 | 0.46 | 5.49 | 130.57 | <0.001 | 0.132 |

| Physical problems | 100 | 2.42 | 2.14 | 100 | 1.26 | 1.77 | 4.17 | 191.31 | <0.001 | 0.081 |

| Cognitive problems | 100 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 100 | 0.31 | 0.60 | 4.42 | 177.58 | <0.001 | 0.090 |

| Parenting ≥ 2 years old child | 93 | 1.55 | 1.61 | 95 | 0.40 | 1.04 | 5.82 | 156.77 | <0.001 | 0.155 |

| Parenting < 2 years old child | 7 | 2.57 | 2.37 | 5 | 1.40 | 0.40 | 2.21 | 8.15 | 0.057 | 0.271 |

| Total score (5 domains) | 100 | 9.63 | 7.12 | 100 | 3.73 | 4.90 | 6.83 | 175.48 | <0.001 | 0.190 |

| Total score ≥ 2 y (6 domains) | 93 | 11.33 | 8.13 | 95 | 4.15 | 5.23 | 7.19 | 156.50 | <0.001 | 0.219 |

| Total score < 2 y (6 domains) | 7 | 10.14 | 8.73 | 5 | 3.80 | 4.97 | 1.45 | 10.00 | 0.177 | 0.174 |

| Thermometer score (overall distress) | 100 | 5.17 | 2.53 | 100 | 2.16 | 2.42 | 8.61 | 198.00 | <0.001 | 0.272 |

| Factor | KMO Measure of Sampling Adequacy | Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Percentage of Variance Explained (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approx. Chi-Square | df | p-Value | |||

| Practical problems | 0.837 | 426.071 | 21 | <0.001 | 49.162 |

| Family/social problems | 0.653 | 140.833 | 6 | <0.001 | 51.343 |

| Emotional problems | 0.828 | 527.417 | 36 | <0.001 | 41.781 |

| Physical problems | 0.849 | 433.768 | 21 | <0.001 | 49.655 |

| Cognitive problems | 0.500 | 59.774 | 1 | <0.001 | 75.551 |

| Parenting ≥ 2 years old child | 0.811 | 283.110 | 10 | <0.001 | 56.373 |

| Parenting < 2 years old child | --- | --- | --- | --- | 67.696 |

| Total score (5 domains) | 0.872 | 2728.621 | 406 | <0.001 | 34.265 |

| Total score ≥ 2 y (6 domains) | 0.865 | 3192.034 | 561 | <0.001 | 32.372 |

| Total score < 2 y (6 domains) | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papaleontiou, A.; Siafaka, V.; Voniati, L.; Gryparis, A.; Georgiou, R.; Tafiadis, D. Greek Version of the Distress Thermometer for Parents of Children with Dysphagia: A Validation Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4260. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124260

Papaleontiou A, Siafaka V, Voniati L, Gryparis A, Georgiou R, Tafiadis D. Greek Version of the Distress Thermometer for Parents of Children with Dysphagia: A Validation Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(12):4260. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124260

Chicago/Turabian StylePapaleontiou, Andri, Vassiliki Siafaka, Louiza Voniati, Alexandros Gryparis, Rafaella Georgiou, and Dionysios Tafiadis. 2025. "Greek Version of the Distress Thermometer for Parents of Children with Dysphagia: A Validation Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 12: 4260. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124260

APA StylePapaleontiou, A., Siafaka, V., Voniati, L., Gryparis, A., Georgiou, R., & Tafiadis, D. (2025). Greek Version of the Distress Thermometer for Parents of Children with Dysphagia: A Validation Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(12), 4260. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124260