The REVIVE Project: From Survival to Holistic Recovery—A Prospective Multicentric Evaluation of Cognitive, Emotional, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Survivors

Abstract

1. Introduction

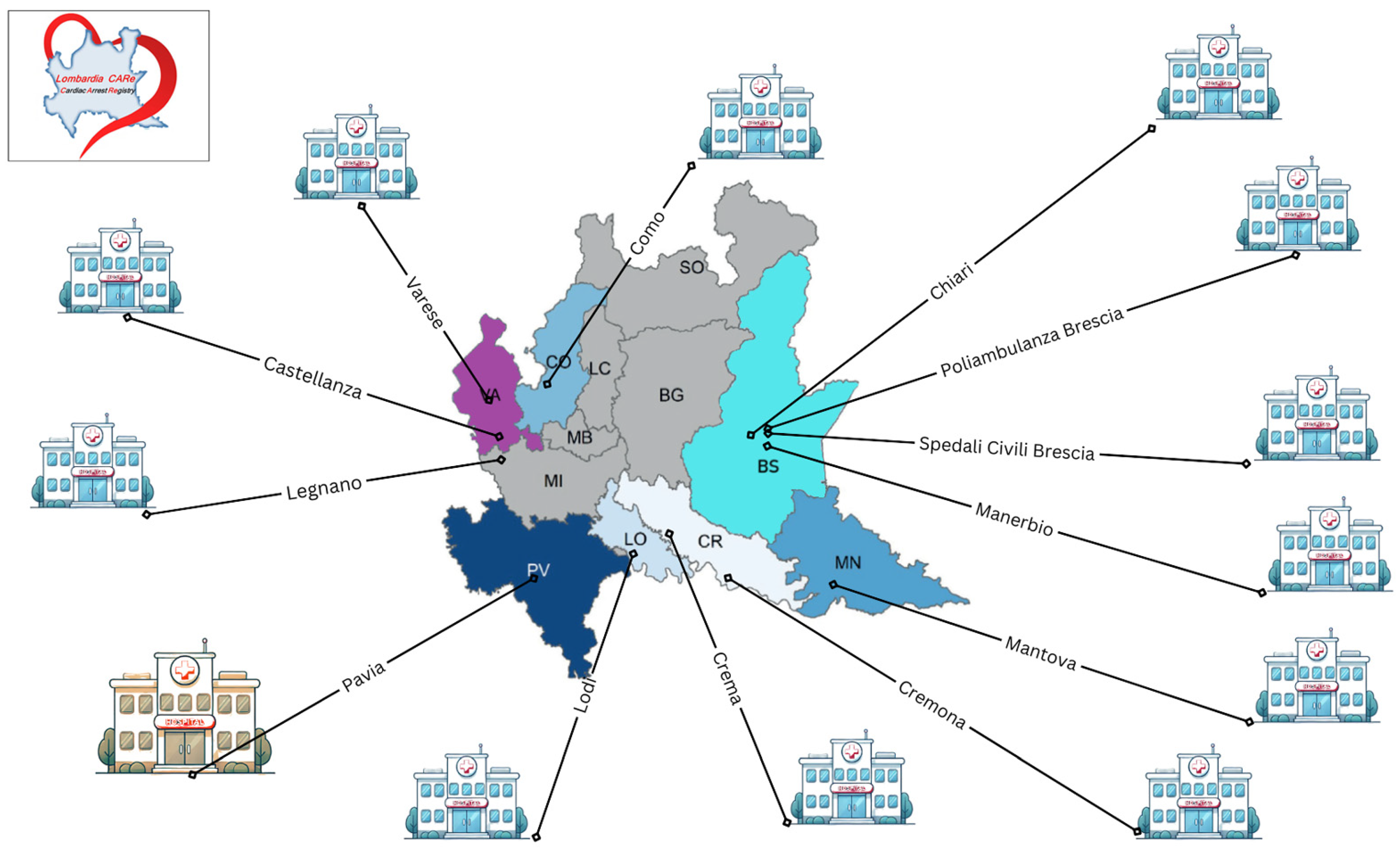

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.1.3. Enrolment and Assessments

2.2. Criteria for Feasibility and Acceptability

2.3. Data Management

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Expected Results

3.1. Investigation of the Feasibility and Acceptability of a Sub-Regional “Hub and Spoke” Model of Post-Discharge Care Delivery

3.2. Identification of Prevalence of Mood Disorders in OHCA Survivors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OHCA | Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest |

| CPC | Cerebral Performance Category |

| mRS | modified Rankin Scale |

| MoCa | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| IES-R | Impact of Event Scale-Revised |

| EQ-5D-5L | EuroQol-5 Dimensions-5 Levels |

| IRC | Italian Resuscitation Council |

| T0, T1, T2, T3, T4 | Time0, Time1, Time2, Time3, Time4 |

| ROSC | Return of Spontaneous Circulation |

Appendix A

| Semi-Structured Clinical Interview (English Translation) |

|---|

|

| Intervista clinica semi-strutturata (original italian version) |

|

| Expected Proportion | Absolute Precision with 95% Confidence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.10 | |

| 0.01 | 381 | 96 | 43 | 24 | 16 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| 0.11 | 3761 | 941 | 418 | 236 | 151 | 105 | 77 | 59 | 47 | 38 |

| 0.21 | 6373 | 1594 | 709 | 399 | 255 | 178 | 131 | 100 | 79 | 64 |

| 0.31 | 8217 | 2055 | 913 | 514 | 329 | 229 | 168 | 129 | 102 | 83 |

| 0.41 | 9293 | 2324 | 1033 | 581 | 372 | 259 | 190 | 146 | 115 | 93 |

| 0.51 | 9600 | 2400 | 1067 | 600 | 384 | 267 | 196 | 150 | 119 | 96 |

| 0.61 | 9139 | 2285 | 1016 | 572 | 366 | 254 | 187 | 143 | 113 | 92 |

| 0.71 | 7910 | 1978 | 879 | 495 | 317 | 220 | 162 | 124 | 98 | 80 |

| 0.81 | 5913 | 1479 | 657 | 370 | 237 | 165 | 121 | 93 | 73 | 60 |

| 0.91 | 3147 | 787 | 350 | 197 | 126 | 88 | 65 | 50 | 39 | 32 |

References

- Gräsner, J.T.; Wnent, J.; Herlitz, J.; Perkins, G.D.; Lefering, R.; Tjelmeland, I.; Koster, R.W.; Masterson, S.; Rossell-Ortiz, F.; Maurer, H.; et al. Survival after Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest in Europe—Results of the EuReCa TWO Study. Resuscitation 2020, 148, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiguchi, T.; Okubo, M.; Nishiyama, C.; Maconochie, I.; Ong, M.E.H.; Kern, K.B.; Wyckoff, M.H.; McNally, B.; Christensen, E.; Tjelmeland, I.; et al. Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest across the World: First Report from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR). Resuscitation 2020, 152, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, F.R.; Primi, R.; Baldi, E.; Compagnoni, S.; Mare, C.; Contri, E.; Reali, F.; Bussi, D.; Facchin, F.; Currao, A.; et al. Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest and Ambient Air Pollution: A Dose-Effect Relationship and an Association with OHCA Incidence. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilja, G.; Ullén, S.; Dankiewicz, J.; Friberg, H.; Levin, H.; Nordström, E.B.; Heimburg, K.; Jakobsen, J.C.; Ahlqvist, M.; Bass, F.; et al. Effects of Hypothermia vs Normothermia on Societal Participation and Cognitive Function at 6 Months in Survivors After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. JAMA Neurol. 2023, 80, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blennow Nordström, E.; Vestberg, S.; Evald, L.; Mion, M.; Segerström, M.; Ullén, S.; Bro-Jeppesen, J.; Friberg, H.; Heimburg, K.; Grejs, A.M.; et al. Neuropsychological Outcome after Cardiac Arrest: Results from a Sub-Study of the Targeted Hypothermia versus Targeted Normothermia after out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest (TTM2) Trial. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.P.; Sandroni, C.; Böttiger, B.W.; Cariou, A.; Cronberg, T.; Friberg, H.; Genbrugge, C.; Haywood, K.; Lilja, G.; Moulaert, V.R.M.; et al. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Guidelines 2021: Post-Resuscitation Care. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 369–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dichman, C.K.; Wagner, M.K.; Joshi, L.V.; Bernild, C. Feeling Responsible but Unsupported: How Relatives of Cardiac Arrest Survivors Experience the Transition from Hospital to Daily Life—A Focus Group Study. Nurs. Open 2020, 8, 2520–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstin, M.; Martina, G.; Theresa, T.; Seraina, H.; Christoph, B.; Tanja, L.; Roshaani, R.; Aurelio, B.; Kai, T.; Christian, E.; et al. Depression and Anxiety in Relatives of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Patients: Results of a Prospective Observational Study. J. Crit. Care 2019, 51, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.K.; Mikkelsen, R.; Budin, S.H.; Lamberg, D.N.; Thrysoe, L.; Borregaard, B. With Fearful Eyes: Exploring Relatives’ Experiences With Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2023, 38, E12–E19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resuscitation Council UK Quality Standards: Survivors|Resuscitation Council UK. Available online: https://www.resus.org.uk/library/quality-standards-cpr/quality-standards-survivors (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Bradfield, M.; Goodfellow, J.; Graham, N.; Haywood, K.; Joshi, V.; Keeble, T.R.; Leckey, S.; MacInnes, L.; Maclean, F.; Menzies, S.; et al. Standard Di Qualità: Sopravvissuti; Resuscitation Council (UK): London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, S.; Presciutti, A.; Anbarasan, D.; Golding, L.; Pavol, M. Abstract 302: NeuroCardiac Comprehensive Care Clinic Seeks to Define and Detect Neurological, Psychiatric, and Functional Sequelae in Cardiac Arrest Survivors. Circulation 2018, 136, A302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mion, M.; Al-Janabi, F.; Islam, S.; Magee, N.; Balasubramanian, R.; Watson, N.; Potter, M.; Karamasis, G.V.; Harding, J.; Seligman, H.; et al. Care After REsuscitation: Implementation of the United Kingdom’s First Dedicated Multidisciplinary Follow-Up Program for Survivors of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Ther. Hypothermia Temp. Manag. 2019, 10, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.K.; Christensen, J.; Christensen, K.A.; Dichman, C.; Gottlieb, R.; Kolster, I.; Hansen, C.M.; Hoff, H.; Hassager, C.; Folke, F.; et al. A Multidisciplinary Guideline-Based Approach to Improving the Sudden Cardiac Arrest Care Pathway: The Copenhagen Framework. Resusc. Plus 2024, 17, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gräsner, J.T.; Herlitz, J.; Tjelmeland, I.B.M.; Wnent, J.; Masterson, S.; Lilja, G.; Bein, B.; Böttiger, B.W.; Rosell-Ortiz, F.; Nolan, J.P.; et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Epidemiology of Cardiac Arrest in Europe. Resuscitation 2021, 161, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mion, M.; Simpson, R.; Johnson, T.; Oriolo, V.; Gudde, E.; Rees, P.; Quinn, T.; Von Vopelius-Feldt, J.; Gallagher, S.; Mozid, A.; et al. British Cardiovascular Intervention Society Consensus Position Statement on Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest 2: Post-Discharge Rehabilitation. Interv. Cardiol. Rev. Res. Resour. 2022, 7, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, K.N.; Camp-Rogers, T.R.; Kotini-Shah, P.; Del Rios, M.; Gossip, M.R.; Moitra, V.K.; Haywood, K.L.; Dougherty, C.M.; Lubitz, S.A.; Rabinstein, A.A.; et al. Sudden Cardiac Arrest Survivorship: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, E654–E685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, E.; Vanini, B.; Savastano, S.; Danza, A.I.; Martinelli, V.; Politi, P. Depression after a Cardiac Arrest: An Unpredictable Issue to Always Investigate For. Resuscitation 2018, 127, e10–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, H.; Lundqvist, C.; Šaltytė Benth, J.; Stavem, K.; Andersen, G.; Henriksen, J.; Drægni, T.; Sunde, K.; Nakstad, E.R. Health-Related Quality of Life after out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest—A Five-Year Follow-up Study. Resuscitation 2021, 162, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deasy, C.; Bray, J.; Smith, K.; Harriss, L.; Bernard, S.; Cameron, P. Functional Outcomes and Quality of Life of Young Adults Who Survive Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Emerg. Med. J. 2013, 30, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isern, C.B.; Nilsson, B.B.; Garratt, A.; Kramer-Johansen, J.; Tjelmeland, I.B.M.; Berge, H.M. Health-Related Quality of Life in Young Norwegian Survivors of out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Related to Pre-Arrest Exercise Habits. Resusc. Plus 2023, 16, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.F.; Pickard, A.S.; Golicki, D.; Gudex, C.; Niewada, M.; Scalone, L.; Swinburn, P.; Busschbach, J. Measurement Properties of the EQ-5D-5L Compared to the EQ-5D-3L across Eight Patient Groups: A Multi-Country Study. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, D.S.; Marmar, C.R. The Impact of Event Scale-Revised. In Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD: A Practitioner’s Handbook; Wilson, J.P., Keane, T.M., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Meregaglia, M.; Malandrini, F.; Finch, A.P.; Ciani, O.; Jommi, C. EQ-5D-5L Population Norms for Italy. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2022, 21, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourke, S.; Bennett, B.; Oluboyede, Y.; Li, T.; Longworth, L.; O’Sullivan, S.B.; Braverman, J.; Soare, I.A.; Shaw, J.W. Estimating the Minimally Important Difference for the EQ-5D-5L and EORTC QLQ-C30 in Cancer. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2024, 22, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Corral, T.; Fabero-Garrido, R.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Navarro-Santana, M.J.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; López-de-Uralde-Villanueva, I. Minimal Clinically Important Differences in EQ-5D-5L Index and VAS after a Respiratory Muscle Training Program in Individuals Experiencing Long-Term Post-COVID-19 Symptoms. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the Framework Method for the Analysis of Qualitative Data in Multi-Disciplinary Health Research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memenga, F.; Sinning, C. Emerging Evidence in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest—A Critical Appraisal of the Cardiac Arrest Center. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cho, Y.; Oh, J.; Kang, H.; Lim, T.H.; Ko, B.S.; Yoo, K.H.; Lee, S.H. Analysis of Anxiety or Depression and Long-Term Mortality Among Survivors of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e237809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| |

|---|---|

| Main Recruiters | Secondary Recruiters |

| Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia | ASST Valle Olona—Ospedale di Gallarate, Gallarate |

| ASST dei Sette Laghi Ospedale di Circolo e Fondazione Macchi, Varese | ASST di Mantova—Ospedale di Asola, Castiglione delle Stiviere |

| ASST di Mantova—Ospedale Carlo Poma, Mantova | Ospedale Sacra Famiglia Fatebenefratelli, Erba |

| ASST Spedali Civili di Brescia—Presidio Spedali Civili, Brescia | ASST di Lecco—Ospedale Alessandro Manzoni, Lecco |

| ASST Lariana—Ospedale Sant’Anna, Como | Ospedale Valduce, Como |

| ASST di Lodi—Ospedale Maggiore, Lodi | Ospedale Moriggia-Pelascini, Gravedona |

| Fondazione Poliambulanza Istituto Ospedaliero, Brescia | ASST Papa Giovanni XXIII—Ospedale Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo |

| ASST Ovest Milanese—Ospedale Civile, Legnano | ASST Valle Olona—Ospedale di Busto Arsizio, Busto Arsizio |

| ASST di Crema—Ospedale Maggiore, Crema | ASST dei Sette Laghi—Ospedale di Cittiglio, Cittiglio |

| ASST di Cremona—Ospedale di Cremona, Cremona | ASST Valtellina e Alto Lario—Ospedale Civile, Sondrio |

| Humanitas Mater Domini, Castellanza | ASST Lariana—Ospedale Sant’Antonio Abate, Cantù |

| Ospedale di Manerbio, ASST Garda, Manerbio, Brescia, Italy | ASST dei Sette Laghi—Ospedale di Tradate, Tradate |

| Ospedale di Chiari, ASST Franciacorta, Chiari, Brescia, Italy | ASST di Pavia—Ospedale Civile, Vigevano |

| Ospedale Erba-Renaldi, Menaggio | |

| Humanitas Research Hospital, Milano | |

| ASST di Pavia—Ospedale di Varzi, Varzi | |

| ASST Melegnano e Martesana—Ospedale di Melegnano, Melegnano | |

| ASST di Mantova—Ospedale di Pieve di Coriano, Pieve di Coriano | |

| ASST di Pavia—Ospedale Civile, Voghera | |

| Assessment Tool | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | Screens for cognitive deficits in memory, executive functions, visuospatial abilities, attention, language, and orientation. |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Screens for anxiety and depression (7 items each). A subscale score > 8 suggests clinically relevant symptoms. |

| EuroQol-5 Dimensions-5 Levels (EQ-5D-5L) | Assesses health-related quality of life across five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression), each on five severity levels. Includes a visual analogue scale (EQ VAS) indicating overall perceived health. |

| Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) | Assesses post-traumatic stress symptoms related to a life-threatening event (e.g., OHCA). A total score ≥ 33 frequently indicates clinically significant distress. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mandrini, A.; Mion, M.; Primi, R.; Bendotti, S.; Currao, A.; Ulmanova, L.; Arnò, C.; Dossi, F.; Fava, C.; Ghiraldin, D.; et al. The REVIVE Project: From Survival to Holistic Recovery—A Prospective Multicentric Evaluation of Cognitive, Emotional, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Survivors. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3631. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113631

Mandrini A, Mion M, Primi R, Bendotti S, Currao A, Ulmanova L, Arnò C, Dossi F, Fava C, Ghiraldin D, et al. The REVIVE Project: From Survival to Holistic Recovery—A Prospective Multicentric Evaluation of Cognitive, Emotional, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Survivors. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(11):3631. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113631

Chicago/Turabian StyleMandrini, Alice, Marco Mion, Roberto Primi, Sara Bendotti, Alessia Currao, Leila Ulmanova, Carlo Arnò, Filippo Dossi, Cristian Fava, Daniele Ghiraldin, and et al. 2025. "The REVIVE Project: From Survival to Holistic Recovery—A Prospective Multicentric Evaluation of Cognitive, Emotional, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Survivors" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 11: 3631. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113631

APA StyleMandrini, A., Mion, M., Primi, R., Bendotti, S., Currao, A., Ulmanova, L., Arnò, C., Dossi, F., Fava, C., Ghiraldin, D., Pegorin, D., Genoni, P., Maffeo, D., Dossena, C., Affinito, S., Bertazzoli, G., Cipullo, F., Fantoni, C., Della Torre, M., ... all the LombardiaCARe Researchers. (2025). The REVIVE Project: From Survival to Holistic Recovery—A Prospective Multicentric Evaluation of Cognitive, Emotional, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Survivors. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(11), 3631. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113631