Dental Adaptation Strategies for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder—A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focused Question

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection of Studies

2.4. Data Extraction

2.4.1. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

2.4.2. Quality Assessment

2.5. Evidence Quality Assessment

3. Results

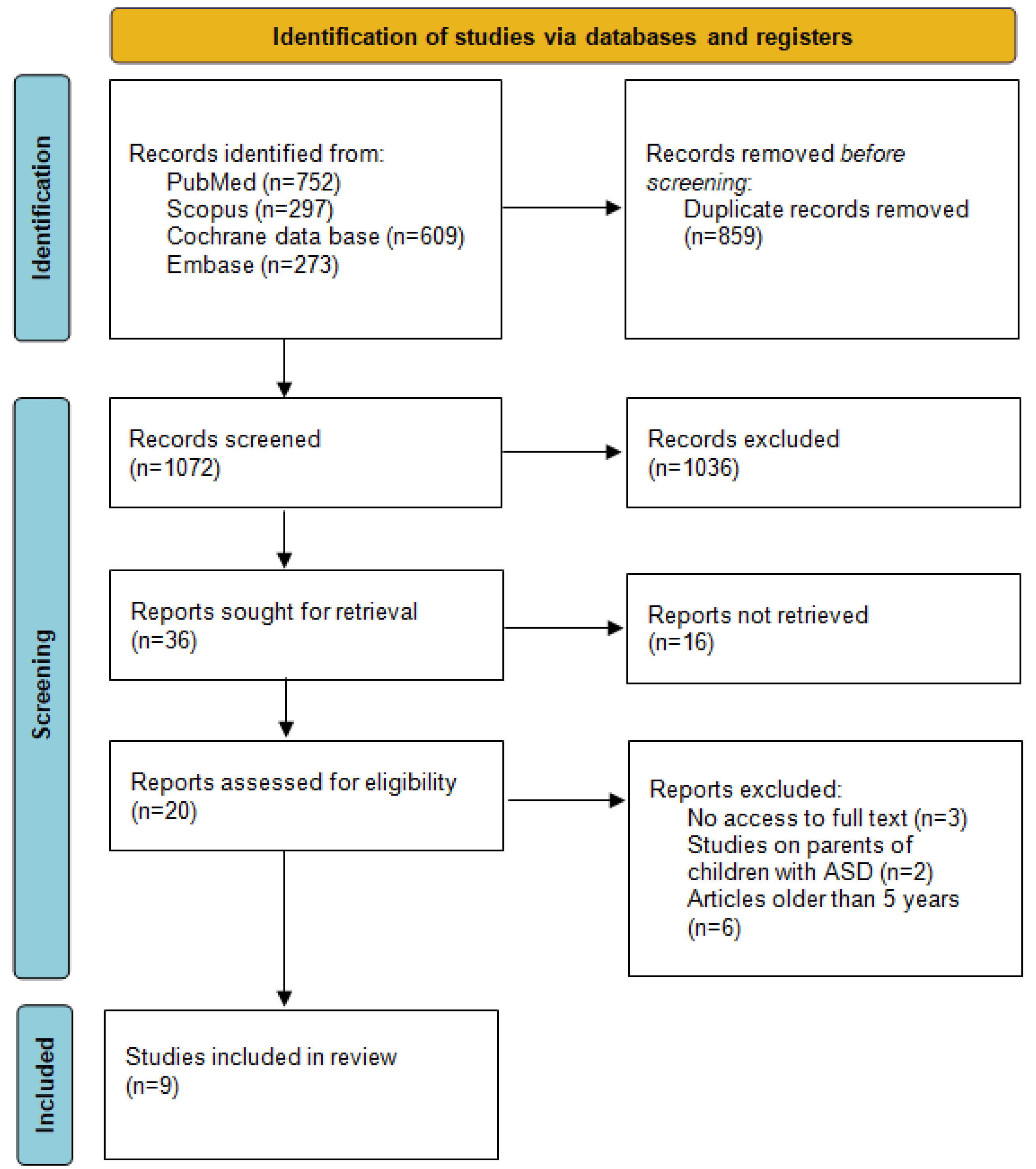

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Risk of Bias Across Studies

3.3. General Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.4. Study Outcomes

3.4.1. Oral Hygiene

3.4.2. Anxiety and Stress Reduction

3.4.3. Behavioral Improvement

3.5. GRADE Ratings

4. Discussion

4.1. General Interpretation and Comparison

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Strengths of the Study

4.4. Implications of the Results for Practice, Policy, and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campisi, L.; Imran, N.; Nazeer, A.; Skokauskas, N.; Azeem, M.W. Autism Spectrum Disorder. Br. Med. Bull. 2018, 127, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, C.Y.; Graham, R.M.; Hughes, C.V. Behaviour Guidance in Dental Treatment of Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2009, 19, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, R.E. A Personalized Multidisciplinary Approach to Evaluating and Treating Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klintwall, L.; Holm, A.; Eriksson, M.; Carlsson, L.H.; Olsson, M.B.; Hedvall, Å.; Gillberg, C.; Fernell, E. Sensory Abnormalities in Autism. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Than, A.; Patterson, G.; Cummings, K.K.; Jung, J.; Cakar, M.E.; Abbas, L.; Bookheimer, S.Y.; Dapretto, M.; Green, S.A. Sensory Over-responsivity and Atypical Neural Responses to Socially Relevant Stimuli in Autism. Autism Res. 2024, 17, 1328–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.-J.; Nagai, Y.; Kumagaya, S.; Ayaya, S.; Asada, M. Atypical Auditory Perception Caused by Environmental Stimuli in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Approach to the Evaluation of Self-Reports. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 888627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, L.I.; Polido, J.C.; Mailloux, Z.; Coleman, G.G.; Cermak, S.A. Oral Care and Sensory Sensitivities in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Spec. Care Dent. 2011, 31, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Brugha, T.S.; Charman, T.; Cusack, J.; Dumas, G.; Frazier, T.; Jones, E.J.H.; Jones, R.M.; Pickles, A.; State, M.W.; et al. Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Shohaimi, S.; Jafarpour, S.; Abdoli, N.; Khaledi-Paveh, B.; Mohammadi, M. The Global Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talantseva, O.I.; Romanova, R.S.; Shurdova, E.M.; Dolgorukova, T.A.; Sologub, P.S.; Titova, O.S.; Kleeva, D.F.; Grigorenko, E.L. The Global Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1071181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, U.; Nowak, A.J. Characteristics of Patients with Autistic Disorder (AD) Presenting for Dental Treatment: A Survey and Chart Review. Spec. Care Dent. 1999, 19, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limeres-Posse, J.; Castano-Novoa, P.; Abeleira-Pazos, M.; Ramos-Barbosa, I. Behavioural Aspects of Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) That Affect Their Dental Management. Med. Oral 2014, 19, e467–e472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, R.; Ruxmohan, S.; Puranik, C.P. Association Between Autism Spectrum Disorder and Dental Anomalies of the Permanent Dentition. Pediatr. Dent. 2021, 43, 307–312. [Google Scholar]

- Suhaib, F.; Saeed, A.; Gul, H.; Kaleem, M. Oral Assessment of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Autism 2019, 23, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, S.N.; Gimenez, T.; Souza, R.C.; Mello-Moura, A.C.V.; Raggio, D.P.; Morimoto, S.; Lara, J.S.; Soares, G.C.; Tedesco, T.K. Oral Health Status of Children and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2017, 27, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carli, E.; Pasini, M.; Pardossi, F.; Capotosti, I.; Narzisi, A.; Lardani, L. Oral Health Preventive Program in Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Children 2022, 9, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piraneh, H.; Gholami, M.; Sargeran, K.; Shamshiri, A.R. Oral Health and Dental Caries Experience among Students Aged 7–15 Years Old with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Tehran, Iran. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hariyani, N.; Oktarina; Shoaib, L.A.; Rohani, M.M.; Hanna, K.M.B.; Lee, H. Caregivers’ Perceptions, Beliefs and Behavior Influence Dental Caries Experience in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Qualitative Study. Saudi Dent. J. 2024, S1013905224002712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.-J.; Hsu, J.-W.; Huang, K.-L.; Bai, Y.-M.; Su, T.-P.; Chen, T.-J.; Chen, M.-H. Autism Spectrum Disorder and Periodontitis Risk. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2023, 154, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlOtaibi, A.; Ben Shaber, S.; AlBatli, A.; AlGhamdi, T.; Murshid, E. A Systematic Review of Population-Based Gingival Health Studies among Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Saudi Dent. J. 2021, 33, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel Júnior, N.S.; De Barros, S.G.; De Jesus Filho, E.; Vianna, M.I.P.; Santos, C.M.L.; Cangussu, M.C.T. Oral Health-Care Practices and Dental Assistance Management Strategies for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Integrative Literature Review. Autism 2024, 28, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshatrat, S.M.; Al-Bakri, I.A.; Al-Omari, W.M. Dental Service Utilization and Barriers to Dental Care for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Jordan: A Case-Control Study. Int. J. Dent. 2020, 2020, 3035463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenney, M.K.; Kogan, M.D.; Crall, J.J. Parental Perceptions of Dental/Oral Health Among Children With and Without Special Health Care Needs. Ambul. Pediatr. 2008, 8, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallea, A.; Vetri, L.; L’Episcopo, S.; Bartolone, M.; Zingale, M.; Di Fatta, E.; d’Albenzio, G.; Buono, S.; Roccella, M.; Elia, M.; et al. Oral Health and Quality of Life in People with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallea, A.; Zuccarello, R.; Roccella, M.; Quatrosi, G.; Donadio, S.; Vetri, L.; Calì, F. Sensory-Adapted Dental Environment for the Treatment of Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Children 2022, 9, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemczyk, W.; Balicz, A.; Lau, K.; Morawiec, T.; Kasperczyk, J. Factors Influencing Peri-Extraction Anxiety: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popple, B.; Wall, C.; Flink, L.; Powell, K.; Discepolo, K.; Keck, D.; Mademtzi, M.; Volkmar, F.; Shic, F. Brief Report: Remotely Delivered Video Modeling for Improving Oral Hygiene in Children with ASD: A Pilot Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 2791–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, H.K.; Weissman, L.; Friedlaender, E.Y.; Neumeyer, A.M.; Friedman, A.J.; Spence, S.J.; Rotman, C.; Krauss, S.; Broder-Fingert, S.; Weitzman, C. Optimizing Care for Autistic Patients in Health Care Settings: A Scoping Review and Call to Action. Acad. Pediatr. 2024, 24, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO Framework to Improve Searching PubMed for Clinical Questions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.F.; Petrie, A. Method Agreement Analysis: A Review of Correct Methodology. Theriogenology 2010, 73, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An Emerging Consensus on Rating Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zink, A.G.; Molina, E.C.; Diniz, M.B. Communication Application for Use During the First Dental Visit for Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Am. Acad. Pediatr. Dent. 2018, 40, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nilchian, F.; Shakibaei, F.; Jarah, Z.T. Evaluation of Visual Pedagogy in Dental Check-Ups and Preventive Practices Among 6–12-Year-Old Children with Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, J.W.; Tsang, P. Visual Schedule System in Dental Care for Patients with Autism: A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2016, 40, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, O.; Lindemann, R. Assessment of the Autistic Patient’s Dental Needs and Ability to Undergo Dental Examination. ASDC J. Dent. Child. 1985, 52, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Isong, I.A.; Rao, S.R.; Holifield, C.; Iannuzzi, D.; Hanson, E.; Ware, J.; Nelson, L.P. Addressing Dental Fear in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study Using Electronic Screen Media. Clin. Pediatr. 2014, 53, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermak, S.A.; Stein Duker, L.I.; Williams, M.E.; Dawson, M.E.; Lane, C.J.; Polido, J.C. Sensory Adapted Dental Environments to Enhance Oral Care for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 2876–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 6.5 (Updated August 2024); Cochrane: London, UK, 2024. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Gandhi, R.; Jackson, J.; Puranik, C.P. A Comparative Evaluation of Video Modeling and Social Stories for Improving Oral Hygiene in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Study. Spec. Care Dent. 2024, 44, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piraneh, H.; Gholami, M.; Sargeran, K.; Shamshiri, A.R. Social Story Based Toothbrushing Education Versus Video-Modeling Based Toothbrushing Training on Oral Hygiene Status Among Male Students Aged 7–15 Years Old with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Tehran, Iran: A Quasi-Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2023, 53, 3813–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljubour, A.; AbdElBaki, M.; El Meligy, O.; Al Jabri, B.; Sabbagh, H. Effect of Culturally Adapted Dental Visual Aids on Oral Hygiene Status during Dental Visits in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Children 2022, 9, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljubour, A.; AbdElBaki, M.; El Meligy, O.; Al-Jabri, B.; Sabbagh, H. Effect of Culturally Adapted Dental Visual Aids on Anxiety Levels in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Children 2023, 10, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljubour, A.A.; AbdElBaki, M.; El Meligy, O.; Al Jabri, B.; Sabbagh, H. Culturally Adapted Dental Visual Aids Effect on Behavior Management during Dental Visits in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2024, 25, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva Moro, J.; Rodrigues, T.D.; Kammer, P.V.; De Camargo, A.R.; Bolan, M. Efficacy of the Video Modeling Technique as a Facilitator of Non-Invasive Dental Care in Autistic Children: Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2024, 54, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirio, S.; Salerno, C.; Mbanefo, S.; Oberti, L.; Paniura, L.; Campus, G.; Cagetti, M.G. Use of Visual Pedagogy to Help Children with ASDs Facing the First Dental Examination: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Children 2022, 9, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalabi, M.A.S.A.; Khattab, N.M.A.; Elheeny, A.A.H. Picture Examination Communication System Versus Video Modelling in Improving Oral Hygiene of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Prospective Randomized Clinical Trial. Pediatr. Dent. 2022, 44, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Stein Duker, L.I.; Como, D.H.; Jolette, C.; Vigen, C.; Gong, C.L.; Williams, M.E.; Polido, J.C.; Floríndez-Cox, L.I.; Cermak, S.A. Sensory Adaptations to Improve Physiological and Behavioral Distress During Dental Visits in Autistic Children: A Randomized Crossover Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2316346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla-Mehta, S.; Miller, T.; Callahan, K.J. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Video Instruction on Social and Communication Skills Training for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review of the Literature. Focus. Autism Other Dev. Disabl. 2010, 25, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccin, S.; Crippa, A.; Nobile, M.; Hardan, A.Y.; Brambilla, P. Video Modeling for the Development of Personal Hygiene Skills in Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 27, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljubour, A.; AbdElBaki, M.A.; El Meligy, O.; Al Jabri, B.; Sabbagh, H. Effectiveness of Dental Visual Aids in Behavior Management of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Child. Health Care 2021, 50, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshid, E.Z. Effectiveness of a Preparatory Aid in Facilitating Oral Assessment in a Group of Saudi Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2017, 38, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagetti, M.; Mastroberardino, S.; Campus, G.; Olivari, B.; Faggioli, R.; Lenti, C.; Strohmenger, L. Dental Care Protocol Based on Visual Supports for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Med. Oral 2015, 20, e598–e604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermak, S.A.; Stein Duker, L.I.; Williams, M.E.; Lane, C.J.; Dawson, M.E.; Borreson, A.E.; Polido, J.C. Feasibility of a Sensory-Adapted Dental Environment for Children With Autism. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 69, 6903220020p1–6903220020p10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duker, L.S.; Polido, J.; Cermak, S. Sensory Adapted Dental Environments to Enhance Oral Care for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics 2021, 147, 779–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.F.; Tengku Azmi, T.M.A.; Malek, W.M.S.W.A.; Mallineni, S.K. The Effect of Multisensory-Adapted Dental Environment on Children’s Behavior toward Dental Treatment: A Systematic Review. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2021, 39, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, J.A.; Ingeholm, J.E.; Wohltjen, S.; Collins, M.; Riddell, C.D.; Gotts, S.J.; Kenworthy, L.; Wallace, G.L.; Simmons, W.K.; Martin, A. Neural Correlates of Taste Reactivity in Autism Spectrum Disorder. NeuroImage Clin. 2018, 19, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerman, N.; Zotti, F.; Chirumbolo, S.; Zangani, A.; Mauro, G.; Zoccante, L. Insights on Dental Care Management and Prevention in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). What Is New? Front. Oral Health 2022, 3, 998831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Batayneh, O.B.; Nazer, T.S.; Khader, Y.S.; Owais, A.I. Effectiveness of a Tooth-Brushing Programme Using the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) on Gingival Health of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2020, 21, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zink, A.G.; Diniz, M.B.; Rodrigues Dos Santos, M.T.B.; Guaré, R.O. Use of a Picture Exchange Communication System for Preventive Procedures in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Pilot Study. Spec. Care Dent. 2016, 36, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, L.M.; Martínez-Sanchis, S.; Silvestre, F.J. Training Adults and Children with an Autism Spectrum Disorder to Be Compliant with a Clinical Dental Assessment Using a TEACCH-Based Approach. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHumaid, J.; Tesini, D.; Finkelman, M.; Loo, C.Y. Effectiveness of the D-TERMINED Program of Repetitive Tasking for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Dent. Child. 2016, 83, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rapin, I.; Tuchman, R.F. Autism: Definition, Neurobiology, Screening, Diagnosis. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 55, 1129–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaber, M.A. Dental Caries Experience, Oral Health Status and Treatment Needs of Dental Patients with Autism. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2011, 19, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraru, D.; Ciuhodaru, T.; Iorga, M. Providing dental care for children with autism spectrum disorders. Int. J. Med. Dent. 2017, 7, 124–130. [Google Scholar]

| Source | Search Term | Filters | Number of Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medline via PubMed | (“autism” OR “autism disorder” OR “autistic disorder” OR “Asperger syndrome” OR “Rett syndrome” OR “autism” OR “autism spectrum disorders” OR “Asperger” OR “developmental disorder” OR “pervasive child development disorders” OR “pervasive developmental disorder” OR “early infantile autism” OR “Kanner syndrome” OR “infantile autism” OR “ASD”) AND (“dentophobia” OR “dental fear” OR “dental anxiety” OR “dental anxieties” OR “adaptation” OR “modeling” OR “dental phobia” OR “odontophobia”) | Randomized Controlled Trials | 752 |

| Web of Science Scopus | (“autism” OR “autism disorder” OR “autistic disorder” OR “Asperger syndrome” OR “Rett syndrome” OR “autism spectrum disorders” OR “Asperger” OR “developmental disorder” OR “pervasive child development disorders” OR “pervasive developmental disorder” OR “early infantile autism” OR “Kanner syndrome” OR “infantile autism” OR “ASD”) AND (“dentophobia” OR “dental fear” OR “dental anxiety” OR “dental anxieties” OR “adaptation” OR “modeling” OR “dental phobia” OR “odontophobia”) | Randomized Controlled Trials | 297 |

| Cochrane database | (“autism” OR “autism disorder” OR “autistic disorder” OR “Asperger syndrome” OR “Rett syndrome” OR “autism” OR “autism spectrum disorders” OR “Asperger” OR “developmental disorder” OR “ASD”) AND (“dentophobia” OR “dental fear” OR “dental anxiety” OR “dental anxieties” OR “adaptation” OR “modeling” OR “dental phobia” OR “odontophobia”) | Trials | 609 |

| Embase | (‘autism’ OR ‘autism disorder’ OR ‘autistic disorder’ OR ‘asperger syndrome’ OR ‘rett syndrome’ OR ‘autism spectrum disorders’ OR ‘asperger’ OR ‘developmental disorder’ OR ‘pervasive child development disorders’ OR ‘pervasive developmental disorder’ OR ‘early infantile autism’ OR ‘kanner syndrome’ OR ‘infantile autism’ OR ‘asd’) AND (‘dentophobia’ OR ‘dental fear’ OR ‘dental anxiety’ OR ‘dental anxieties’ OR ‘adaptation’ OR ‘modeling’ OR ‘dental phobia’ OR ‘odontophobia’) | Randomized Controlled Trials | 273 |

| Inclusion criteria: Full text available English language Randomized trials Patients aged <18 years Low or moderate risk of bias Autism spectrum disorder diagnosis confirmed Published in last 5 years | Exclusion criteria: Case reports/Case series Narrative reviews Systematic reviews Meta-analysis Non-English language publications Letters to editor Conference papers Non-peer-reviewed literature Gray literature Studies based on parents’ education |

| Study | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Aljubour et al. (2022) [42] | Aljubour et al. (2023) [43] | Aljubour et al. (2024) [44] | Cirio et al. (2022) [46] | Da Silva Moro et al. (2024) [45] | Gandhi et al. (2024) [40] | Piraneh et al. (2023) [41] | Shalabi et al. (2022) [47] | Stein Duker et al. (2023) [48] |

| Random allocation |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Study was blinded |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Calculated study group |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Balanced study groups (+/−10%) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria clearly defined |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Autism spectrum disorder diagnosis confirmed |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Patients not excluded due to ASD severity |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Primary clinical outcome(s) measured objectively |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Adequate statistical analysis |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Total | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Risk of bias | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low |

—Indicates that the article has met the criterion;

—Indicates that the article has met the criterion;  —Indicates that the article has not met the criterion.

—Indicates that the article has not met the criterion.| Author/Year | Country | Study Desing | Sample Size Calculation | Patients | Sex | Age (Years) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Mean (±SD) | Range | |||||

| Aljubour et al. (2022) [42] | Saudi Arabia | BRCT | Yes | 64 | 21 | 43 | 8.2 | 6–12 |

| Aljubour et al. (2023) [43] | Saudi Arabia | BRCT | Yes | 64 | 21 | 43 | 8.2 | 6–12 |

| Aljubour et al. (2024) [44] | Saudi Arabia | BRCT | Yes | 64 | 21 | 43 | 8.2 | 6–12 |

| Cirio et al. (2022) [46] | Italy | BRCT | Yes | 84 | 12 | 72 | 7.54 ± 2.42 | 3–15 |

| Da Silva Moro et al. (2024) [45] | Brazil | BRCT | Yes | 40 | 4 | 36 | 7.12 ± 2.24 | 4–12 |

| Gandhi et al. (2024) [40] | USA | RCT | No | 25 | 2 | 23 | 9.5 ± 3.1 | 4–17 |

| Piraneh et al. (2023) [41] | Iran | RCT | Yes | 133 | 0 | 133 | 11.57 ± 2.29 | 7–15 |

| Shalabi et al. (2022) [47] | Egypt | RCT | Yes | 50 | 15 | 35 | 8.6±1.1 | <18 |

| Stein Duker et al. (2023) [48] | USA | RCT | No | 138 | 24 | 114 | 9.16 ±1.99 | 6–12 |

| Author/Year | Treatment Groups | Number of Dental Visits | Evaluation | Main Results | Follow-Up Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aljubour et al. (2022) [42] | 1. Control group—regular DVA 2. Test group—culturally adapted DVA | 2 | Plaque Index Scores | There was a notable enhancement in the oral health status of both groups following the utilization of the dental visual aids (p < 0.001, p < 0.001), respectively. A significant improvement in OH status was observed in the test group in comparison to the control group (p = 0.030). The two dental visual aids demonstrated efficacy in enhancing oral health status in children with autism spectrum disorder. | 4 weeks |

| Aljubour et al. (2023) [43] | 1. Control group—regular DVA 2. Test group—culturally adapted DVA | 2 | Anxiety Scale for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder | A statistically significant reduction in anxiety levels was observed in the test group compared to the control group (p < 0.001). The culturally adapted dental visual aids were demonstrated to effectively reduce anxiety levels in children with autism spectrum disorder during dental visits. | 4 weeks |

| Aljubour et al. (2024) [44] | 1. Control group—regular DVA 2. Test group—culturally adapted DVA | 2 | Observational Scale of Behavioral Distress | There was a notable alteration in behavioral patterns among the test group (p < 0.001), whereas no statistically significant change was observed in the control group (p = 0.077). Concerning behavioral patterns, the experimental group demonstrated a significantly superior performance compared to the control group (p < 0.001). | 4 weeks |

| Cirio et al. (2022) [46] | 1. Video Group 2. Photo Group | 1 | Frankl Behavioral Scale; Evaluation of the steps needed to complete first dental examination (1–8) | The video group demonstrated a greater number of steps achieved; however, the comparison between groups was statistically significant only for the preliminary steps (p = 0.04). The proportion of subjects who were rated as cooperative was comparable between the two groups. The findings of this study reinforce the notion that behavioral intervention should be employed as an efficacious strategy to equip subjects with ASDs with the requisite skills to undergo a dental examination. | - |

| Da Silva Moro et al. (2024) [45] | 1. Control group—did not watch video before consultation 2. Test group—watched the video | Up to 5 | Frankl Behavioral Scale; Mean service time of each visit; Mean number of visits to the dentist required to complete all steps (1–12) of oral physical examination and dental prophylaxis | The results demonstrated that the mean number of consultations in the intervention group was 1.5 (±1.53), while in the control group, it was 2 (±1.77) (p ≤ 0.05). The utilization of the video modeling technique has the potential to reduce the frequency of dental consultations in children with autism. | Up to five visits |

| Gandhi et al. (2024) [40] | 1. VM 2. TSS | 2 | Plaque scores; Gingival scores; The effectiveness of the intervention was based on a 5-point Likert Scale | Significant improvements in plaque and gingival scores were observed for the VM (0.68 ± 0.20; 0.59 ± 0.15) and TSS (0.50 ± 0.11; 0.40 ± 0.10) groups at the post-intervention stage when compared to the pre-intervention visits. No statistically significant differences were observed in plaque or gingival scores between the VM and TSS groups. The VM group demonstrated encouraging outcomes in terms of caregivers’ perceptions regarding their children’s acceptance of oral hygiene practices. | 4 weeks |

| Piraneh et al. (2023) [41] | 1. Control group—Social story 2. Test group—VM | 2 | OHI-S; Oral health knowledge and attitude scores of the parents | The improvement in OHI-S was markedly greater in the intervention group. The use of video modeling based on modern technologies in an educational intervention for tooth brushing can result in a greater improvement in oral hygiene status than traditional social stories (standard education) in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). | 4 weeks |

| Shalabi et al. (2022) [47] | 1. VM 2. PECS | 4 | OHI-S; CI-s; DI-s | The VM group exhibited a statistically significant reduction in mean OHI-S scores in comparison to the PECS group over the follow-up period (p < 0.001). At the three-, six-, and 12-month marks, the mean differences in the OHI-S scores were 0.30, 0.58, and 0.57, respectively. For both groups, there was a moderate correlation between the severity of ASD and OHI-S scores at 12 months. | 12 months |

| Stein Duker et al. (2023) [48] | 1. RDE 2. SADE | 2 | Electrodermal activity; Tonic skin conductance level; Frequency per minute of nonspecific skin conductance responses; Children’s Dental Behavior Rating Scale | Children showed less stress during dental care in SADE than in RDE. There was a notable decrease in sympathetic activity and an increase in relaxation during SADE dental care. No significant differences were observed in the non-specific skin conductance responses. The frequency and duration of behavioral distress were significantly lower in the SADE group. There was a correlation between physiological stress and behavioral distress during the dental cleaning. | 6 months |

| Outcome | Number of Studies | Number of Patients | Study Design | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Quality of Evidence | Importance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Hygiene | Four | 272 | RCT | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | None detected | High | Critical |

| Anxiety and Stress | Two | 88 | RCT | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | None detected | Moderate | Critical |

| Behavioral Improvement | Five | 237 | RCT | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | None detected | High | Important |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prynda, M.; Pawlik, A.A.; Niemczyk, W.; Wiench, R. Dental Adaptation Strategies for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder—A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7144. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237144

Prynda M, Pawlik AA, Niemczyk W, Wiench R. Dental Adaptation Strategies for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder—A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(23):7144. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237144

Chicago/Turabian StylePrynda, Magdalena, Agnieszka Anna Pawlik, Wojciech Niemczyk, and Rafał Wiench. 2024. "Dental Adaptation Strategies for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder—A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 23: 7144. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237144

APA StylePrynda, M., Pawlik, A. A., Niemczyk, W., & Wiench, R. (2024). Dental Adaptation Strategies for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder—A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(23), 7144. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237144