Rectal Cancer following Local Excision of Rectal Adenomas with Low-Grade Dysplasia—A Multicenter Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

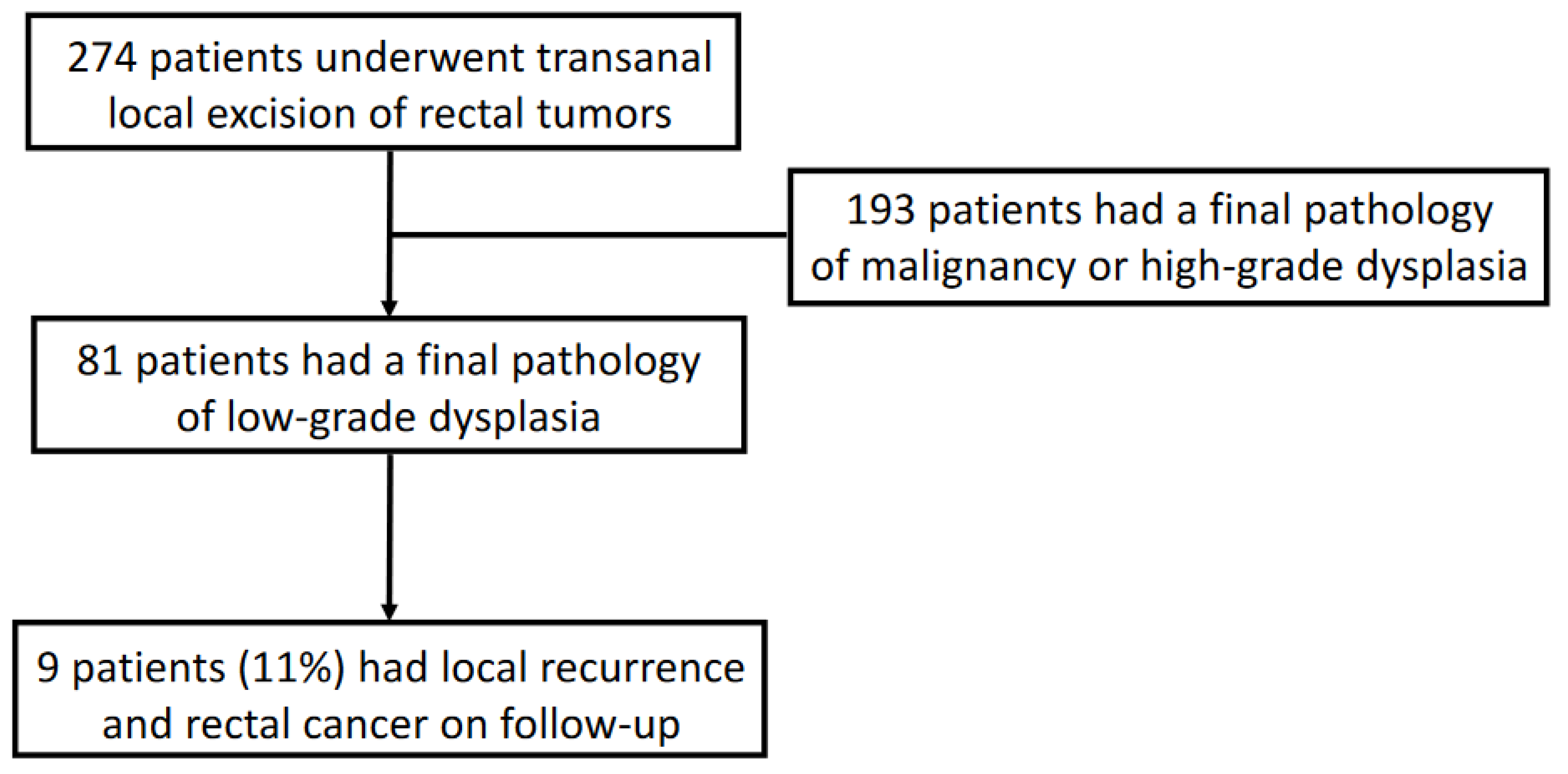

3. Results

3.1. Preoperative Workup

3.2. Surgical Techniques and Operational Findings

3.3. Complication and Pathology Reports

3.4. Follow-Up, Recurrence, and Rectal Cancer Rate

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vogelstein, B.; Fearon, E.R.; Hamilton, S.R.; Kern, S.E.; Preisinger, A.C.; Leppert, M.; Smits, A.M.; Bos, J.L. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 319, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Winawer, S.J.; Zauber, A.G.; O’Brien, M.J.; Ho, M.N.; Gottlieb, L.; Sternberg, S.S.; Waye, J.D.; Bond, J.; Schapiro, M.; Stewart, E.T.; et al. Randomized Comparison of Surveillance Intervals after Colonoscopic Removal of Newly Diagnosed Adenomatous Polyps. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 328, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, D.J.; Greenberg, E.R.; Beach, M.; Sandler, R.S.; Ahnen, D.; Haile, R.W.; Burke, C.A.; Snover, D.C.; Bresalier, R.S.; McKeown-Eyssen, G.; et al. Colorectal cancer in patients under close colonoscopic surveillance. Gastroenterology 2005, 129, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arditi, C.; Gonvers, J.-J.; Burnand, B.; Minoli, G.; Oertli, D.; Lacaine, F.; Dubois, R.; Vader, J.-P.; Filliettaz, S.S.; Peytremann-Bridevaux, I.; et al. Appropriateness of colonoscopy in Europe (EPAGE II) – Surveillance after polypectomy and after resection of colorectal cancer. Endoscopy 2009, 41, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lieberman, D.A.; Rex, D.K.; Winawer, S.J.; Giardiello, F.M.; Johnson, D.A.; Levin, T.R. Guidelines for Colonoscopy Surveillance After Screening and Polypectomy: A Consensus Update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 844–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waye, J.D.; Braunfeld, S. Surveillance Intervals after Colonoscopic Polypectomy. Endoscopy 1982, 14, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winawer, S.J.; Zauber, A.G.; Fletcher, R.H.; Stillman, J.S.; O’Brien, M.J.; Levin, B.; Smith, R.A.; Lieberman, D.A.; Burt, R.W.; Levin, T.R.; et al. Guidelines for Colonoscopy Surveillance after Polypectomy: A Consensus Update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American Cancer Society. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2006, 56, 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Affi Koprowski, M.; Lu, K.C. Colorectal Cancer Screening and Postpolypectomy Surveillance. Dis. Colon Rectum 2021, 64, 932–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, S.; Keller, D. Why the conventional parks transanal excision for early stage rectal cancer should be abandoned. Dis. Colon Rectum 2015, 58, 1211–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, D.; Colin, J.-F.; Remue, C.; Jamart, J.; Kartheuser, A. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: Long-term experience, indication expansion, and technical improvements. Surg. Endosc. 2012, 26, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, W.; Igov, I.; Issa, N.; Gimelfarb, Y.; Duek, S.D. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for upper rectal tumors. Surg. Endosc. 2014, 28, 2066–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavien, P.A.; Barkun, J.; De Oliveira, M.L.; Vauthey, J.N.; Dindo, D.; Schulick, R.D.; De Santibañes, E.; Pekolj, J.; Slankamenac, K.; Bassi, C.; et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: Five-year experience. Ann. Surg. 2009, 250, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonithon-Kopp, C.; Piard, F.; Fenger, C.; Cabeza, E.; O’Morain, C.; Kronborg, O.; Faivre, J. Colorectal adenoma characteristics as predictors of recurrence. Dis. Colon Rectum 2004, 47, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Stolk, R.U.; Beck, G.J.; Baron, J.A.; Haile, R.; Summers, R.; Group, P.P.S. Adenoma characteristics at first colonoscopy as predictors of adenoma recurrence and characteristics at follow-up. Gastroenterology 1998, 115, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, S.D.; Kim, H.M.; Schoenfeld, P. Incidence of advanced adenomas at surveillance colonoscopy in patients with a personal history of colon adenomas: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006, 64, 614–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordero, C.; Leo, E.; Cayuela, A.; Bozada, J.M.; Garcia, E.; Pizarro, M.A. Validity of early colonoscopy for the treatment of adenomas missed by initial endoscopic examination. Rev. Esp. De Enferm. Dig. 2001, 93, 519–528. [Google Scholar]

- Nusko, G.; Mansmann, U.; Kirchner, T.; Hahn, E.G. Risk related surveillance following colorectal polypectomy. Gut 2002, 51, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schatzkin, A.; Lanza, E.; Corle, D.; Lance, P.; Iber, F.; Caan, B.; Shike, M.; Weissfeld, J.; Burt, R.; Cooper, M.R.; et al. Lack of Effect of a Low-Fat, High-Fiber Diet on the Recurrence of Colorectal Adenomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Perez, B.; Andrade-Ribeiro, G.D.; Hunter, L.; Atallah, S. A systematic review of transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) from 2010 to 2013. Tech. Coloproctol. 2014, 18, 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, D.K.; Boland, C.R.; Dominitz, J.A.; Giardiello, F.M.; Johnson, D.A.; Kaltenbach, T.; Levin, T.R.; Lieberman, D.; Robertson, D.J. Colorectal Cancer Screening: Recommendations for Physicians and Patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, S.R.; Hull, T.L.; Hyman, N.; Maykel, J.A.; Read, T.E.; Whitlow, C.B. The ASCRS Manual of Colon and Rectal Surgery; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Provenzale, D.; Ness, R.M.; Llor, X.; Weiss, J.M.; Abbadessa, B.; Cooper, G.; Early, D.S.; Friedman, M.; Giardiello, F.M.; Glaser, K.; et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Colorectal Cancer Screening, Version 2.2020. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020, 18, 1312–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, R.; Duek, S.D.; Issa, N.; Khoury, W. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for large benign rectal tumors; where are the limits? Int. J. Surg. 2016, 29, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosty, C.; Webster, F.; Nagtegaal, I.D.; Dataset Authoring Committee for the development of the IDfPRoCEB. Pathology Reporting of Colorectal Local Excision Specimens: Recommendations from the International Collaboration on Cancer Reporting (ICCR). Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | (n = 81) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 81 |

| Age at operation (years)—mean ± SD | 65 ± 11 |

| Male sex—n (%) | 52 (64%) |

| Body mass index (BMI)—mean ± SD | 26.6 ± 4.8 |

| Co-morbidities ≥ 1 − n (%) | 54 (67%) |

| ASA class I—n (%) | 6 |

| ASA class II—n (%) | 47 |

| ASA class III—n (%) | 8 |

| ASA class IV—n (%) | 3 |

| Missing data on ASA | 17 |

| Preoperative assessment (Endoscopy) | |

| Distance from anal verge (cm)—mean ± SD | 7 ± 3.5 |

| Largest diameter of lesion (cm)—mean ± SD | 3.3 ± 3.1 |

| Type of polyp | |

| Sessile polyp—n (%) | 40 (49%) |

| Pedunculated polyp—n (%) | 13 (16%) |

| Missing data—n (%) | 28 (35%) |

| Preoperative biopsy report | |

| Low-grade dysplasia (LGD) | 49 (60%) |

| High-grade dysplasia (HGD) | 12 (15%) |

| Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma | 3 (4%) |

| Moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma | 2 (2%) |

| Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma | 0 |

| Missing data | 15 (19%) |

| Preoperative imaging | |

| ERUS was performed—n (%) | 37 (46%) |

| MRI Pelvis was performed—n (%) | 8 (10%) |

| Characteristic | (n = 81) |

|---|---|

| Operative technique | |

| TAE—n (%) | 20 (25%) |

| TAMIS—n (%) | 36 (44%) |

| TEM—n (%) | 25 (31%) |

| Distance from anal verge (cm)—mean ± SD | 7.2 ± 4.3 |

| Largest diameter of lesion (cm)—mean ± SD | 2.8 ± 1.6 |

| Predominant rectal wall location | |

| Posterior wall | 19 (23%) |

| Anterior wall | 18 (22%) |

| Lt lateral wall | 21 (26%) |

| Rt lateral wall | 13 (16%) |

| Unknown | 10 (13%) |

| Depth of resection | |

| Full-thickness resection | 68 (84%) |

| Partial-thickness resection | 6 (7%) |

| Mucosal resection | 4 (5%) |

| Piecemeal (in >1 piece) | 3 (4%) |

| Defect closure approach | |

| Running suture | 49 (61%) |

| Interrupted sutures | 27 (33%) |

| Defect left open | 5 (6%) |

| Intra-operative complications | 0 |

| Laparoscopy added—no complication found | 1 (1%) |

| LOS—Length of stay (days)—mean ± SD | 3.6 ± 1.8 |

| Postoperative complications | 12 (15%) |

| Bleeding | 2 (2%) |

| Wound infection/Abscess | 6 (7%) |

| Cardiac/Respiratory complication | 2 (2%) |

| Transient fecal incontinence | 2 (2%) |

| Clavien-Dindo ≥ 3B | 4 (5%) |

| Final pathology | |

| Largest diameter of lesion (cm)—mean ± SD | 3.2 ± 1.8 |

| Margins | |

| Clear margins >3 mm | 47 (58%) |

| Clear margins <3 mm | 18 (22%) |

| Involved margins | 4 (5%) |

| Missing data | 12 (15%) |

| Added treatment after pathology—Redo LE | 1 (1%) |

| Characteristic | (n = 9) |

|---|---|

| Local recurrence | 9 |

| Systemic recurrence | 0 |

| Time interval from LE to cancerous recurrence (months)—mean ± SD (range) | 19.3 ± 14.5 (5.2–54) |

| Number of patients that recurred under 24 months | 7 (78%) |

| Original largest diameter of lesion (cm)—mean (range) | 3.5 (1.5–7) |

| Original margins | |

| Clear margins >3 mm | 6/9 |

| Clear margins <3 mm | 0 |

| Involved margins | 3/9 |

| Original depth of resection | |

| Full-thickness resection | 4/9 |

| Partial-thickness resection | 1/9 |

| Mucosal resection | 1/9 |

| Piecemeal (in >1 piece) | 3/9 |

| Original operative platform used | |

| TAE—p/n | 6/9 |

| TAMIS—p/n | 1/9 |

| TEM—p/n | 2/9 |

| Treatment after recurrence | |

| Re-do local excision | 7 |

| LAR | 1 |

| Radiotherapy | 1 |

| Follow-up time (months)—mean ± SD | 25.3 ± 22.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rudnicki, Y.; Horesh, N.; Harbi, A.; Lubianiker, B.; Green, E.; Raveh, G.; Slavin, M.; Segev, L.; Gilshtein, H.; Khalifa, M.; et al. Rectal Cancer following Local Excision of Rectal Adenomas with Low-Grade Dysplasia—A Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031032

Rudnicki Y, Horesh N, Harbi A, Lubianiker B, Green E, Raveh G, Slavin M, Segev L, Gilshtein H, Khalifa M, et al. Rectal Cancer following Local Excision of Rectal Adenomas with Low-Grade Dysplasia—A Multicenter Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(3):1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031032

Chicago/Turabian StyleRudnicki, Yaron, Nir Horesh, Assaf Harbi, Barak Lubianiker, Eraan Green, Guy Raveh, Moran Slavin, Lior Segev, Haim Gilshtein, Muhammad Khalifa, and et al. 2023. "Rectal Cancer following Local Excision of Rectal Adenomas with Low-Grade Dysplasia—A Multicenter Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 3: 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031032

APA StyleRudnicki, Y., Horesh, N., Harbi, A., Lubianiker, B., Green, E., Raveh, G., Slavin, M., Segev, L., Gilshtein, H., Khalifa, M., Barenboim, A., Wasserberg, N., Khaikin, M., Tulchinsky, H., Issa, N., Duek, D., Avital, S., & White, I. (2023). Rectal Cancer following Local Excision of Rectal Adenomas with Low-Grade Dysplasia—A Multicenter Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(3), 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031032