The Relationship between Oral Health and Schizophrenia in Advanced Age—A Narrative Review in the Context of the Current Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

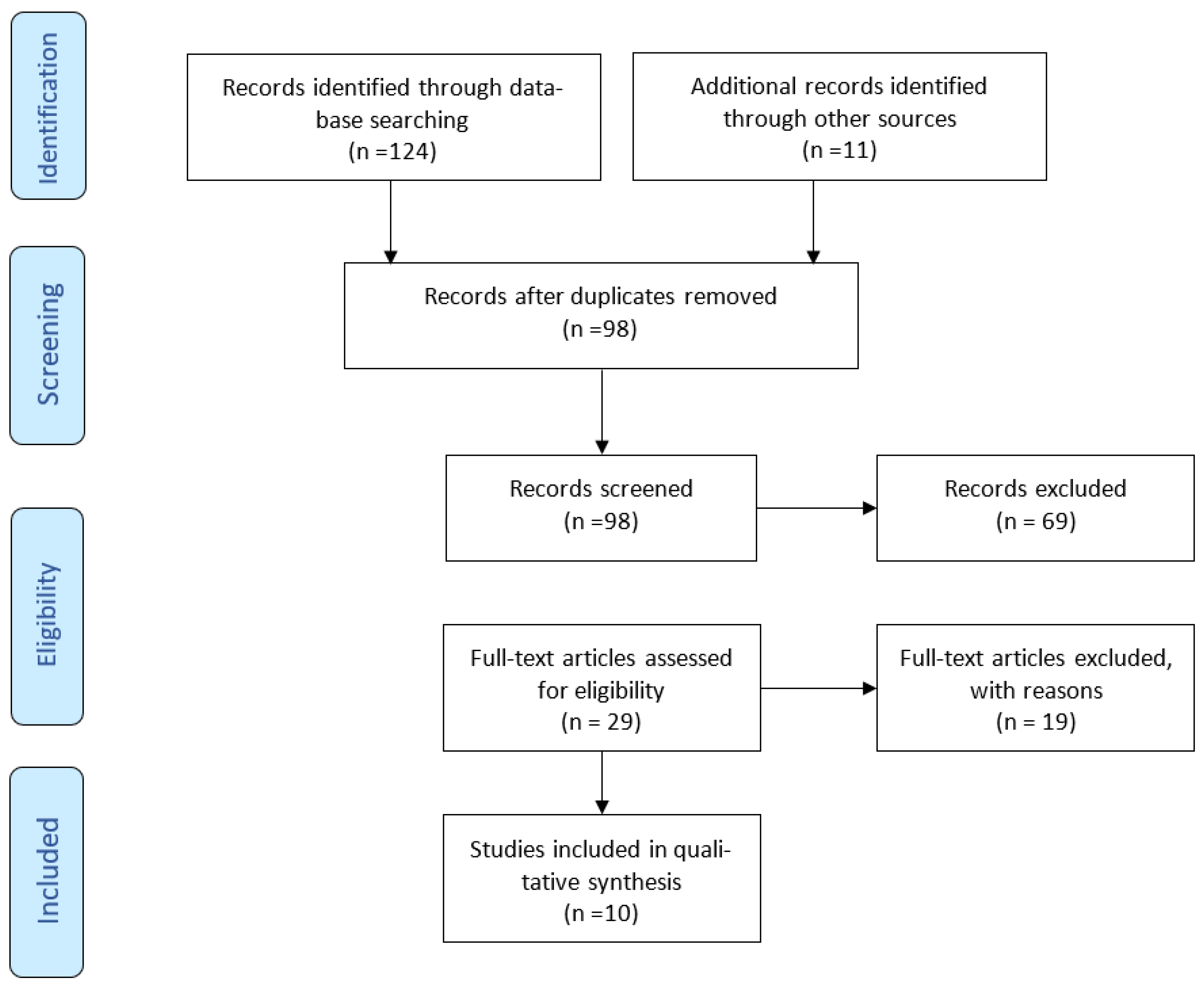

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Relationship between Etiology of Schizophrenia and Oral Health

4.2. Oral Manifestations

4.2.1. Dental Caries

4.2.2. Deficient Oral Hygiene

4.2.3. Xerostomia

4.2.4. Effects of Tobacco

4.2.5. Temporomandibular Disorders

4.2.6. Tardive Dyskinesia

4.3. Dental Management

5. Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, T.; Fang, Y.; Wang, L.; Gu, L.; Tang, J. Exosome and exosomal contents in schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2023, 163, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics, 11th ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mueser, K.T.; McGurk, S.R. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2004, 363, 2063–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Horvitz-Lennon, M.; Post, E.P.; McCarthy, J.F.; Cruz, M.; Welsh, D.; Blow, F.C. Oral health in Veterans Affairs patients diagnosed with serious mental illness. J. Public Health Dent. 2007, 67, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiyak, H.A.; Reichmuth, M. Barriers to and Enablers of Older Adults’ Use of Dental Services. J. Dent. Educ. 2005, 69, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Pk, P.; Gupta, R. Necessity of oral health intervention in schizophrenic patients—A review. Nepal J. Epidemiol. 2016, 6, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, F.B.; McNary, S.W.; Brown, C.H.; Kreyenbuhl, J.; Goldberg, R.W.; Dixon, L.B. Somatic Healthcare Utilization Among Adults With Serious Mental Illness Who Are Receiving Community Psychiatric Services. Med. Care 2003, 41, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janardhanan, T.; Cohen, C.I.; Kim, S.; Rizvi, B.F. Dental Care and Associated Factors Among Older Adults With Schizophrenia. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2011, 142, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Miyabe, S.; Ishibashi, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Goto, M.; Hasegawa, S.; Miyachi, H.; Fujita, K.; Nagao, T. Oral hygiene status and factors related to oral health in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2022, 20, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, D.Y.J.; Thomson, W.M.; Subramaniam, M.; Abdin, E.; Ang, K.-Y. The oral health of long-term psychiatric inpatients in Singapore. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 266, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zusman, S.P.; Ponizovsky, A.M.; Dekel, D.; Masarwa, A.-E.; Ramon, T.; Natapov, L.; Grinshpoon, A. An assessment of the dental health of chronic institutionalized patients with psychiatric disease in Israel. Spéc. Care Dent. 2010, 30, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, F.; Siu-Paredes, F.; Maitre, Y.; Amador, G.; Rude, N. A qualitative study on experiences of persons with schizophrenia in oral-health-related quality of life. Braz. Oral Res. 2021, 35, e050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinshpoon, A.; Zusman, S.P.; Weizman, A.; Ponizovsky, A.M. Dental Health and the Type of Antipsychotic Treatment in Inpatients with Schizophrenia. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2015, 52, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wey, M.C.; Loh, S.; Doss, J.G.; Abu Bakar, A.K.; Kisely, S. The oral health of people with chronic schizophrenia: A neglected public health burden. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2016, 50, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tani, H.; Uchida, H.; Suzuki, T.; Shibuya, Y.; Shimanuki, H.; Watanabe, K.; Den, R.; Nishimoto, M.; Hirano, J.; Takeuchi, H.; et al. Dental conditions in inpatients with schizophrenia: A large-scale multi-site survey. BMC Oral Health 2012, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, K.-Y.; Yang, N.-P.; Chou, P.; Chiu, H.-J.; Chi, L.-Y. Factors associated with dental caries among institutionalized residents with schizophrenia in Taiwan: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, K.-Y.; Yang, N.-P.; Chou, P.; Chi, L.-Y.; Chiu, H.-J. The Relationship between Body Mass Index, the Use of Second-Generation Antipsychotics, and Dental Caries among Hospitalized Patients with Schizophrenia. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2011, 41, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joury, E.; Kisely, S.; Watt, R.; Ahmed, N.; Morris, A.; Fortune, F.; Bhui, K. Mental Disorders and Oral Diseases: Future Research Directions. J. Dent. Res. 2023, 102, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Price, J.; Ryder, S.; Siskind, D.; Solmi, M.; Kisely, S. Prevalence of dental disorders among people with mental illness: An umbrella review. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2022, 56, 949–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahli, B.F.; Alrasheed, N.M.; Alabdulrazaq, R.S.; Alasmari, D.S.; Ahmed, M.M. Association between schizophrenia and periodontal disease in relation to cortisol levels: An ELISA-based descriptive analysis. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2021, 57, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, U.; Schwarz, M.J.; Müller, N. Inflammatory processes in schizophrenia: A promising neuroimmunological target for the treatment of negative/cognitive symptoms and beyond. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 132, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saetre, P.; Emilsson, L.; Axelsson, E.; Kreuger, J.; Lindholm, E.; Jazin, E. Inflammation-related genes up-regulated in schizophrenia brains. BMC Psychiatry 2007, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, D.J.; Benjet, C.; Gureje, O.; Lund, C.; Scott, K.M.; Poznyak, V.; van Ommeren, M. Integrating mental health with other non-communicable diseases. BMJ 2019, 364, l295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senusi, A.; Higgins, S.; Fortune, F. The influence of oral health and psycho-social well-being on clinical outcomes in Behçet’s disease. Rheumatol. Int. 2018, 38, 1873–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomaa, N.; Tenenbaum, H.; Glogauer, M.; Quiñonez, C. The Biology of Social Adversity Applied to Oral Health. J. Dent. Res. 2019, 98, 1442–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashioka, S.; Inoue, K.; Miyaoka, T.; Hayashida, M.; Wake, R.; Oh-Nishi, A.; Inagaki, M. The Possible Causal Link of Periodontitis to Neuropsychiatric Disorders: More Than Psychosocial Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matevosyan, N.R. Oral Health of Adults with Serious Mental Illnesses: A Review. Community Ment. Health J. 2009, 46, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco-Ortega, E.; Segura-Egea, J.; Cordoba-Arenas, S.; Jimenez-Guerra, A.; Monsalve-Guil, L.; Lopez-Lopez, J. A comparison of the dental status and treatment needs of older adults with and without chronic mental illness in Sevilla, Spain. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cirugía Bucal 2013, 18, e71–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keepers, G.A.; Fochtmann, L.J.; Anzia, J.M.; Benjamin, S.; Lyness, J.M.; Mojtabai, R.; Servis, M.; Walaszek, A.; Buckley, P.; Lenzenweger, M.F.; et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 33, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Stroup, T.S.; Gray, N. Management of common adverse effects of antipsychotic medications. World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterer, G. Why do patients with schizophrenia smoke? Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2010, 23, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Yang, Y.; Dutra, E.H.; Robinson, J.L.; Wadhwa, S. Temporomandibular Joint Disorders in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 1213–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbuz, O.; Alatas, G.; Kurt, E. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder signs in patients with schizophrenia. J. Oral Rehabil. 2009, 36, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowsky, J.M.; Thomas, E.; Simmons, R.K.; Edwards, L.P.; Johnson, C.D. 4 case reports: Dental management of patients with drug induced Tardive Dyskinesia (TD). J. Dent. Health Oral Disord. Ther. 2014, 1, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Swager, L.; Morgan, S. Psychotropic-induced dry mouth: Don’t overlook this potentially serious side effect. Curr. Psychiatry 2011, 10, 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, A.; Miyachi, H.; Tanaka, K.; Chikazu, D.; Miyaoka, H. Relationship between xerostomia and psychotropic drugs in patients with schizophrenia: Evaluation using an oral moisture meter. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2016, 41, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, D.; Randall, C.; Baker, S.; Borrelli, B.; Burgette, J.; Gibson, B.; Heaton, L.; Kitsaras, G.; McGrath, C.; Newton, J. Consensus Statement on Future Directions for the Behavioral and Social Sciences in Oral Health. J. Dent. Res. 2022, 101, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Literature | Age (Years) | Participants | Measurements | Type of Study | Dental Challenge | Dental Manifestation | Dental Consideration | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kurokawa et al. [9] | 63 (SD = 13) | 249 hospitalized PWS | Oral hygiene (DMFT, calculus index, debris Index) and Revised Oral Assessment Guide. Related factors: hospitalization, chlorpromazine equivalents [CPZE], age, Barthel index [BI], frequency of cleaning teeth, and self-oral hygiene ability. | Cross-sectional | Positive correlation: Age and DMFT. Males have worse oral hygiene than females. High doses of antipsychotics associated with a decline in OH. | Poor oral hygiene. Being a male and having low activities of daily living were associated with poor oral hygiene. Advanced age associated with dental caries. | Male patients and patients with low ADL, advanced age, and inability to perform OH. | Older male patients with poor activities of daily living and low self-oral hygiene abilities have poor oral hygiene. |

| Joanna Ngo et al. [10] | 24–80 (Age group: 60–80 = 64 patients) | 191 inpatients (88.5% diagnosed with schizophrenia); 64 out of 191 subjects were elderly (age 60–80). | DMFT, salivary flow, soft tissue, gum inflammation, calculus. Medication, number of years since admission, dental visit status. | Cross-sectional | Dental caries experience > in older pts. Smokers were first-time visits. Most take antipsychotics with anticholinergics = dry mouth. | Males and older people had higher caries experience. Salivary gland hypofunction (SGH) associated with higher DMFT. Classical antipsychotics lower mean saliva flow and SGH. Pain (27.7%). | Pts needed scaling, OHI, dentures, extractions, mandibular dyskinesia, and restorations. Changing from reactive dentistry to preventive dentistry. | Poor OH. Males are at greater risk of dental caries. Pts are suffering from dry mouth, and typical antipsychotics and anticholinergics should be used with caution. |

| Zusman et al. [11] | 53 (SD = 16) | 254 patients; 64 out of 254 subjects were elderly (age 55–91). | Psychiatric diagnosis: majority 82.3% schizophrenia. Dental status: DMFT | Cross-sectional | The highest DMFT score was found in the 75–91 age group. Schizophrenia patients had the highest mean of carious and missing teeth. | Caries, missing teeth, high number of extractions due to caries/pain. Dentists are unwilling to invest in complex conservative or rehabilitative treatments because of the difficulty in treating psychiatric patients. High number of decayed and missing teeth. | Improving the oral health of the chronic psychotic patient. Dental treatment must be made available for these patients. More preventive and restorative care is needed. Dental services must be available in hospital/institution systems. | Need for prevention of dental disease and provision of dental treatment in long-term inpatients with psychiatric disease. |

| Denis et al. [12] | 45.8 (SD = 9.5) | 20 PWS | Experience of oral symptoms: dental and facial pain, oral dysfunctions, side effects of treatment. The stress created by dental care. Attitudes. Autonomy dimension in oral health. | Qualitative | Patient management. More extractions. | Dental pain, jaw pain, disfunctions: swallowing, chewing, talking. Dry mouth, burning sensation, taste of food changed due to medications, anxiety regarding treatment, trismus. Anticholinergic drugs on OHRQoL in older people and PWS. Side effects of antipsychotic drugs. | Poor oral health and OHRQoL. Support patients with daily oral hygiene. | PWS views and experiences are based on dimensions related to the experience of oral symptoms. |

| Grinshpoon et al. [13] | 51.4 (SD = 14.5) | 348 hospitalized patients from 14 psychiatric institutions in Israel. | DMFT index. Data on medication (typical or atypical antipsychotics). | Cross-sectional | Missing teeth and decayed teeth. | Medications: typical antipsychotics affect fine motor movements, decreasing the ability to brush. Both (typ/atyp) cause tardive dyskinesia (megative effect on teeth and occlusion). Both have anticholinergic side effects, causing xerostomia (caries). They take anticholinergics to reduce the extrapyramidal effects of typical antipsychotics. | Monotherapy with atypicals is superior to both atypical/typical. The choice is on the psychiatrist but the benefit of atypicals regarding dental health should be considered. | Patients taking atypicals have better dental health than patients on typical or with a combination of both. |

| Janarthanan et al. [8] | 61.5 (SD = 5.6) | 198 patients living in New York City. | Krause’s model of illness behavior in later life | Cross-sectional | <2 dental visits/year. Financial strain and lower executive cognitive function | “Denture or teeth problems”, higher levels of oral dyskinesia. | Targeting people with financial and cognitive problems to provide dental care. | Old schizophrenic adults did not receive two dental visits per year. |

| Chek Wey et al. [14] | 54.8 (SD = 16) | 543 PWS from a psychiatric institution. | DMFT, CPITN, and DI. | Cross-sectional | Poor oral hygiene, side effects of psychotropic medications, smoking and difficulty in optimal dental care (<access) | Increase in DMFT, gingival bleeding, and periodontal disease. | Preventive care, promotion of oral hygiene. | Levels of decay and periodontal disease were greatest in older patients due to neglect. |

| Tani et al. [15] | 55.6 (SD = 13.4) | 523 PWS from psychiatric hospitals in Japan. | DMFT, smoking status, daily intake of sweets, dry mouth, frequency of daily tooth brushing, and tremor. | Cross-sectional. | Smoking, tremor burden, and less frequent tooth brushing. | Increase in DMFT and increased risk of physical comorbidities. | Physicians be aware of aged smoking patients with schizophrenia and caregivers should be advised to encourage and help patients to perform tooth brushing more frequently. | Older age, smoking, severe tremor, and less frequent tooth brushing were negatively related with dental condition in patients with schizophrenia. |

| Kuan-Yu Chu et al. [16] | 65+ | 122 PWS from psychiatric hospital in Taiwan. | DMFT, NRT, and care index. | Cross-sectional | Effects of FGA, older age, lower educational level, and longer hospital stays. | NRT being <24 and high levels of dental caries | No effects of FGA. Prolonged stay in institutions when decision-makers are planning for preventive strategies of oral health for institutionalized residents with schizophrenia | Older age had an independent effect on the risk of a high DMFT score. |

| Yu Chu et al. [17] | 50.6 (SD = 10.88) | 878 PWS from psychiatric hospital in Taiwan. | DMFT and BMI | Cross-sectional | Effects of SGA, older age and underweight. | Increase in DMFT | No effects of SGA. Psychologists and dentists should pay attention to the relationship between BMI and dental caries among hospitalized schizophrenic patients. | Older age and being underweight is a significant factor associated with the increased risk of dental caries in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santhosh Kumar, S.; Cantillo, R.; Ye, D. The Relationship between Oral Health and Schizophrenia in Advanced Age—A Narrative Review in the Context of the Current Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6496. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206496

Santhosh Kumar S, Cantillo R, Ye D. The Relationship between Oral Health and Schizophrenia in Advanced Age—A Narrative Review in the Context of the Current Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(20):6496. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206496

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanthosh Kumar, Sanjana, Raquel Cantillo, and Dongxia Ye. 2023. "The Relationship between Oral Health and Schizophrenia in Advanced Age—A Narrative Review in the Context of the Current Literature" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 20: 6496. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206496

APA StyleSanthosh Kumar, S., Cantillo, R., & Ye, D. (2023). The Relationship between Oral Health and Schizophrenia in Advanced Age—A Narrative Review in the Context of the Current Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(20), 6496. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206496