Exploring the Association between Gambling-Related Offenses, Substance Use, Psychiatric Comorbidities, and Treatment Outcome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Treatment

2.3. Measures

- DSM-5M-5 [1]

- South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) [31]

- Symptom Checklist-Revised (SCL-90-R) [33]

- Impulsive Behavior Scale (UPPS-P) [35]

- Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised (TCI-R) [37]

- Other sociodemographic and clinical variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Sample

3.2. Comparison of the Clinical Profile between the Groups

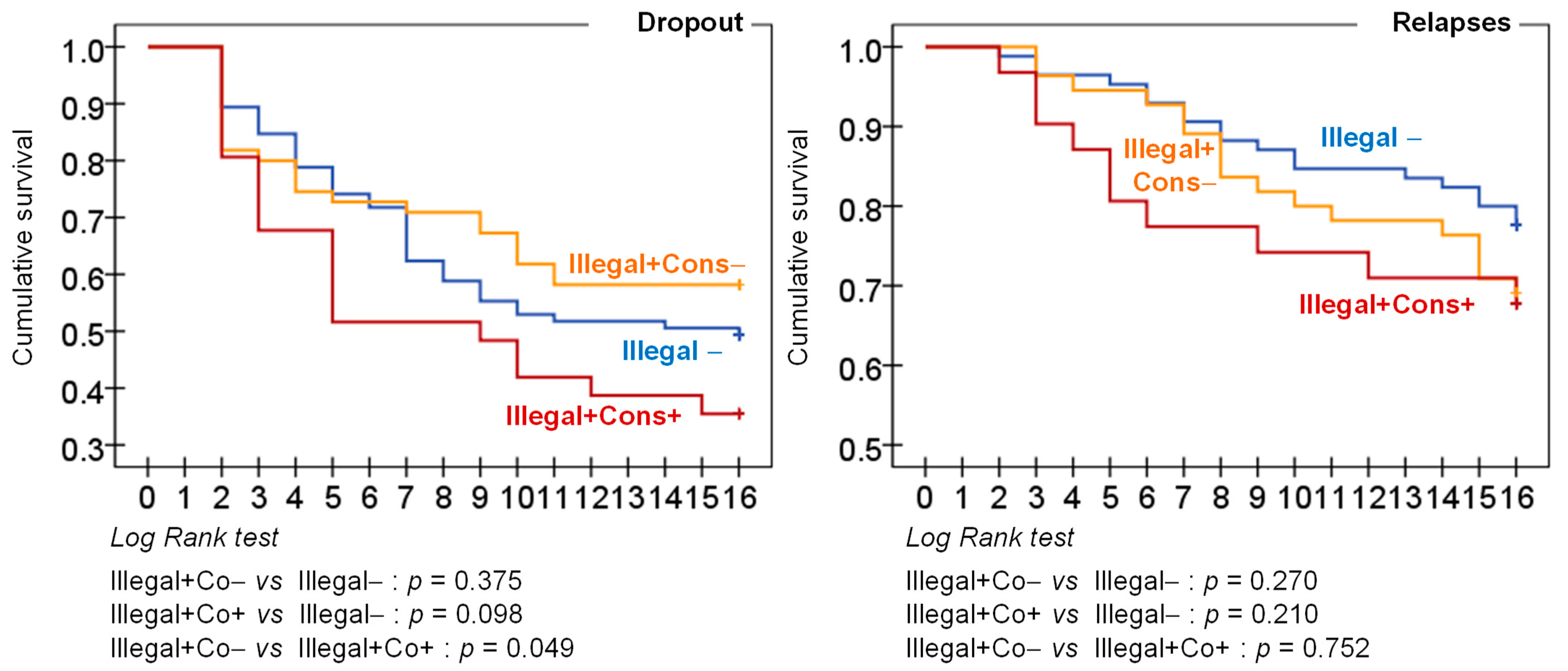

3.3. Comparison of the Therapy Outcomes between the Groups

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Potenza, M.N.; Balodis, I.M.; Derevensky, J.; Grant, J.E.; Petry, N.M.; Verdejo-Garcia, A.; Yip, S.W. Gambling Disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2019, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauth-Bühler, M.; Mann, K.; Potenza, M.N. Pathological Gambling: A Review of the Neurobiological Evidence Relevant for Its Classification as an Addictive Disorder. Addict. Biol. 2017, 22, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miela, R.; Cubała, W.J.; Mazurkiewicz, D.W.; Jakuszkowiak-Wojten, K. The Neurobiology of Addiction. A Vulnerability/Resilience Perspective. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2018, 32, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, H.; Tsurumi, K.; Murao, T.; Mizuta, H.; Kawada, R.; Murai, T.; Takahashi, H. Framing Effects on Financial and Health Problems in Gambling Disorder. Addict. Behav. 2020, 110, 106502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miela, R.J.; Cubała, W.J.; Jakuszkowiak-Wojten, K.; Mazurkiewicz, D.W. Gambling Behaviours and Treatment Uptake among Vulnerable Populations during COVID-19 Crisis. J. Gambl. Issues 2021, 48, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, C.R.; Finkeldey, J.G.; Rocheleau, G.C. Confounding Bias in the Relationship Between Problem Gambling and Crime. J. Gambl. Stud. 2021, 37, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolphe, A.; Khatib, L.; van Golde, C.; Gainsbury, S.M.; Blaszczynski, A. Crime and Gambling Disorders: A Systematic Review. J. Gambl. Stud. 2018, 35, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, B.; Plauborg, R.; Ekholm, O.; Larsen, C.V.L.; Juel, K. Problem Gambling Associated with Violent and Criminal Behaviour: A Danish Population-Based Survey and Register Study. J. Gambl. Stud. 2016, 32, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folino, J.O.; Abait, P.E. Pathological Gambling and Criminality. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2009, 22, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero, R.; Penelo, E.; Stinchfield, R.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Aymamí, N.; Gómez-Peña, M.; Fagundo, A.B.; Sauchelli, S.; Islam, M.A.; Menchón, J.M.; et al. Contribution of Illegal Acts to Pathological Gambling Diagnosis: DSM-5 Implications. J. Addict. Dis. 2014, 33, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, N.M.; Blanco, C.; Stinchfield, R.; Volberg, R. An Empirical Evaluation of Proposed Changes for Gambling Diagnosis in the DSM-5. Addiction 2013, 108, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, N.E.; Stinchfield, R.; McCready, J.; McAvoy, S.; Ferentzy, P. Endorsement of Criminal Behavior Amongst Offenders: Implications for DSM-5 Gambling Disorder. J. Gambl. Stud. 2016, 32, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestre-Bach, G.; Granero, R.; Vintró-Alcaraz, C.; Juvé-Segura, G.; Marimon-Escudero, M.; Rivas-Pérez, S.; Valenciano-Mendoza, E.; Mora-Maltas, B.; del Pino-Gutierrez, A.; Gómez-Peña, M.; et al. Youth and Gambling Disorder: What about Criminal Behavior? Addict. Behav. 2021, 113, 106684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorsane, M.A.; Reynaud, M.; Vénisse, J.L.; Legauffre, C.; Valleur, M.; Magalon, D.; Fatséas, M.; Chéreau-Boudet, I.; Guilleux, A.; Challet-Bouju, G.; et al. Gambling Disorder-Related Illegal Acts: Regression Model of Associated Factors. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre-Bach, G.; Steward, T.; Granero, R.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Talón-Navarro, M.T.; Cuquerella, À.; Baño, M.; Moragas, L.; del Pino-Gutiérrez, A.; Aymamí, N.; et al. Gambling and Impulsivity Traits: A Recipe for Criminal Behavior? Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- April, L.M.; Weinstock, J. The Relationship Between Gambling Severity and Risk of Criminal Recidivism. J. Forensic Sci. 2018, 63, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.D.; Lister, J.J.; Struble, C.A.; Cairncross, M.; Carr, M.M.; Ledgerwood, D.M. Client and Clinician-Rated Characteristics of Problem Gamblers with and without History of Gambling-Related Illegal Behaviors. Addict. Behav. 2018, 84, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potenza, M.N.; Steinberg, M.A.; McLaughlin, S.D.; Wu, R.; Rounsaville, B.J.; O’Malley, S.S. Illegal Behaviors in Problem Gambling: Analysis of Data from a Gambling Helpline. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2000, 28, 389–403. [Google Scholar]

- Mestre-Bach, G.; Steward, T.; Granero, R.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Talón-Navarro, M.T.; Cuquerella, À.; del Pino-Gutiérrez, A.; Aymamí, N.; Gómez-Peña, M.; Mallorquí-Bagué, N.; et al. Sociodemographic and Psychopathological Predictors of Criminal Behavior in Women with Gambling Disorder. Addict. Behav. 2018, 80, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Granero, R.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Sauvaget, A.; Fransson, A.; Hakansson, A.; Mestre-Bach, G.; Steward, T.; Stinchfield, R.; Moragas, L.; et al. A Comparison of DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Gambling Disorder in a Large Clinical Sample. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, D.L.; McAvoy, S.; Saunders, C.; Gillam, L.; Saied, A.; Turner, N.E. Problem Gambling and Mental Health Comorbidity in Canadian Federal Ofenders. Crim. Justice Behav. 2012, 39, 1373–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, G.; Stadler, M.A. Criminal Behavior Associated with Pathological Gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 1999, 15, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledgerwood, D.M.; Weinstock, J.; Morasco, B.J.; Petry, N.M. Clinical Features and Treatment Prognosis of Pathological Gamblers with and without Recent Gambling-Related Illegal Behavior. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2007, 35, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vintró-Alcaraz, C.; Mestre-Bach, G.; Granero, R.; Cuquerella, À.; Talón-Navarro, M.T.; Valenciano-Mendoza, E.; Mora-Maltas, B.; del Pino-Gutiérrez, A.; Gómez-Peña, M.; Moragas, L.; et al. Identifying Associated Factors for Illegal Acts among Patients with Gambling Disorder and ADHD. J. Gambl. Stud. 2021, 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apa. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; Volume 1, ISBN 0-89042-334-2. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Aymamí-Sanromà, M.N.; Gómez-Peña, M.; Álvarez-Moya, E.M.; Vallejo, J. Protocols de Tractament Cognitivoconductual Pel Joc Patològic i d’altres Addiccions No Tòxiques. [Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment Protocols for Pathological Gambling and Other Nonsubstance Addictions]; Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge: Barcelona, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Tremblay, J.; Stinchfield, R.; Granero, R.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Mestre-Bach, G.; Steward, T.; del Pino-Gutiérrez, A.; Baño, M.; Moragas, L.; et al. The Involvement of a Concerned Significant Other in Gambling Disorder Treatment Outcome. J. Gambl. Stud. 2016, 33, 937–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre-Bach, G.; Steward, T.; Granero, R.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; del Pino-Gutiérrez, A.; Mallorquí-Bagué, N.; Mena-Moreno, T.; Vintró-Alcaraz, C.; Moragas, L.; Aymamí, N.; et al. The Predictive Capacity of DSM-5 Symptom Severity and Impulsivity on Response to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Gambling Disorder: A 2-Year Longitudinal Study. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 55, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.W.; Wölfling, K.; Dickenhorst, U.; Beutel, M.E.; Medenwaldt, J.; Koch, A. Recovery, Relapse, or Else? Treatment Outcomes in Gambling Disorder from a Multicenter Follow-up Study. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 43, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesieur, H.R.; Blume, S.B. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A New Instrument for the Identification of Pathological Gamblers. Am. J. Psychiatry 1987, 144, 1184–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeburúa, E.; Báez, C.; Fernández, J.; Páez, D. Cuestionario de Juego Patológico de South Oaks (SOGS): Validación Española. Análisis y Modif. Conduct. 1994, 74, 769–791. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.R. SCL-90-R: Symptom Checklist-90-R. Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manuall—II for the Revised Version; Clinical Psychometric Research: Towson, MD, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.R. SCL-90-R: Cuestionario de 90 Síntomas-Manual; TEA Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside, S.P.; Lynam, D.R.; Miller, J.D.; Reynolds, S.K. Validation of the UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale: A Four Factor Model of Impulsivity. ProQuest Diss. Theses 2001, 574, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdejo-García, A.; Lozano, Ó.; Moya, M.; Alcázar, M.Á.; Pérez-García, M. Psychometric Properties of a Spanish Version of the UPPS–P Impulsive Behavior Scale: Reliability, Validity and Association With Trait and Cognitive Impulsivity. J. Pers. Assess. 2010, 92, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloninger, C. The Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised; Washington University: St Louis, MS, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Zotes, J.A.; Bayón, C.; Montserrat, C.; Valero, J.; Labad, A.; Cloninger, C.R. Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised (TCI-R). Standardization and Normative Data in a General Population Sample. Actas Españolas Psiquiatr. 2004, 32, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead, A.B. Four Factor Index of Social Status. Yale Journal of Sociology. 2011, 8, 21–51. [Google Scholar]

- Stata-Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17; Stata Press Publication, StataCorp LLC.: College Station, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Finner, H.; Roters, M. On the False Discovery Rate and Expected Type I Errors. Biometrical J. 2001, 43, 985–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, J.B.; Willett, J.B. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, C.; Hasin, D.S.; Petry, N.; Stinson, F.S.; Grant, B.F. Sex Differences in Subclinical and DSM-IV Pathological Gambling: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, S.; Thomas, S.L.; Bellringer, M.E.; Cassidy, R. Women and Gambling-Related Harm: A Narrative Literature Review and Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Services 16 Studies in Human Society 1605 Policy and Administration. Harm Reduct. J. 2019, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, S. Study of Gambling and Health in Victoria: Findings from the Victorian Prevalence Study 2014; Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation: Victoria, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Swisher, R.R.; Dennison, C.R. Educational Pathways and Change in Crime Between Adolescence and Early Adulthood. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2016, 53, 840–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández de Frutos, T. Social Stratification and Delinquency. Forty Years of Sociological Discrepancy. Rev. Int. Sociol. 2006, 45, 199–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Farrington, D. Age and Crime. In Crime Justice; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero, A.; Farrington, D.; Blumstein, A. Key Issues in Criminal Career Research: New Analyses of the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kuoppamäki, S.M.; Kääriäinen, J.; Lind, K. Examining Gambling-Related Crime Reports in the National Finnish Police Register. J. Gambl. Stud. 2013, 30, 967–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.E.; Preston, D.L.; Saunders, C.; McAvoy, S.; Jain, U. The Relationship of Problem Gambling to Criminal Behavior in a Sample of Canadian Male Federal Offenders. J. Gambl. Stud. 2009, 25, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinchfield, R. Reliability, Validity, and Classification Accuracy of the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS). Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 27, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Toneatto, T.; Potenza, M.N.; Petry, N.; Ladouceur, R.; Hodgins, D.C.; El-Guebaly, N.; Echeburua, E.; Blaszczynski, A. A Framework for Reporting Outcomes in Problem Gambling Treatment Research: The Banff, Alberta Consensus. Addiction 2006, 101, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniaci, G.; La Cascia, C.; Picone, F.; Lipari, A.; Cannizzaro, C.; La Barbera, D. Predictors of Early Dropout in Treatment for Gambling Disorder: The Role of Personality Disorders and Clinical Syndromes. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 257, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronzitti, S.; Soldini, E.; Smith, N.; Clerici, M.; Bowden-Jones, H. Gambling Disorder: Exploring Pre-Treatment and In-Treatment Dropout Predictors. A UK Study. J. Gambl. Stud. 2017, 33, 1277–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neale, J.; Nettleton, S.; Pickering, L. Gender Sameness and Difference in Recovery from Heroin Dependence: A Qualitative Exploration. Int. J. Drug Policy 2014, 25, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (n = 171) | Illegal− (n = 85) | Illegal + Cons− (n = 55) | Illegal + Cons+ (n = 31) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | p | ||

| Gender | Women | 12 | 7.0% | 7 | 8.2% | 4 | 7.3% | 1 | 3.2% | 0.643 |

| Men | 159 | 93.0% | 78 | 91.8% | 51 | 92.7% | 30 | 96.8% | ||

| Education | Primary | 88 | 51.5% | 42 | 49.4% | 31 | 56.4% | 15 | 48.4% | 0.740 |

| Secondary | 77 | 45.0% | 41 | 48.2% | 22 | 40.0% | 14 | 45.2% | ||

| University | 6 | 3.5% | 2 | 2.4% | 2 | 3.6% | 2 | 6.5% | ||

| Civil status | Single | 82 | 48.0% | 33 | 38.8% | 31 | 56.4% | 18 | 58.1% | 0.163 |

| Married | 64 | 37.4% | 39 | 45.9% | 17 | 30.9% | 8 | 25.8% | ||

| Divorced | 25 | 14.6% | 13 | 15.3% | 7 | 12.7% | 5 | 16.1% | ||

| Social Index | Mean-high | 1 | 0.6% | 1 | 1.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.965 |

| Mean | 13 | 7.6% | 6 | 7.1% | 4 | 7.3% | 3 | 9.7% | ||

| Mean-low | 66 | 38.6% | 32 | 37.6% | 23 | 41.8% | 11 | 35.5% | ||

| Low | 91 | 53.2% | 46 | 54.1% | 28 | 50.9% | 17 | 54.8% | ||

| Employment | Unemployed | 68 | 39.8% | 32 | 37.6% | 22 | 40.0% | 14 | 45.2% | 0.764 |

| Employed | 103 | 60.2% | 53 | 62.4% | 33 | 60.0% | 17 | 54.8% | ||

| Age (years-old); mean-SD | 41.38 | 13.40 | 45.86 | 14.00 | 36.31 | 10.90 | 38.10 | 11.82 | <0.001 * | |

| Illegal− (n = 85) | Illegal + Cons− (n = 55) | Illegal + Cons+ (n = 31) | Illegal + Co− vs. Illegal− | Illegal + Co+ vs. Illegal− | Illegal + Co+ vs. Illegal + Co− | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p | |d| | p | |d| | p | |d| | |

| Age (years-old) | 45.86 | 14.00 | 36.31 | 10.90 | 38.10 | 11.82 | <0.001 * | 0.76 † | 0.004 * | 0.60 † | 0.531 | 0.16 |

| Onset GD (years-old) | 31.35 | 12.62 | 25.42 | 8.87 | 25.18 | 8.18 | 0.003 * | 0.54 † | 0.008 * | 0.58 † | 0.922 | 0.03 |

| Duration GD (years) | 6.05 | 7.32 | 5.87 | 6.09 | 7.74 | 6.64 | 0.883 | 0.03 | 0.238 | 0.24 | 0.224 | 0.29 |

| DSM-5 criteria | 6.47 | 2.06 | 7.53 | 1.78 | 7.74 | 1.73 | 0.002 * | 0.55 † | 0.002 * | 0.67 † | 0.619 | 0.12 |

| SOGS-total | 9.69 | 2.99 | 11.53 | 3.21 | 12.55 | 3.36 | 0.001 * | 0.59 † | <0.001 * | 0.90 † | 0.149 | 0.31 |

| Debts (euros) | 5757 | 9943 | 9914 | 14,639 | 9219 | 14,195 | 0.050 * | 0.33 | 0.049 * | 0.28 | 0.744 | 0.05 |

| SCL-90R Somatization | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 1.47 | 0.90 | 0.694 | 0.07 | 0.001 * | 0.70 † | 0.003 * | 0.63 † |

| SCL-90R Obsessive-comp. | 1.05 | 0.86 | 1.37 | 0.88 | 1.53 | 0.89 | 0.037 * | 0.36 | 0.009 * | 0.55 † | 0.395 | 0.19 |

| SCL-90R Sensitivity | 0.93 | 0.89 | 1.13 | 0.80 | 1.49 | 0.83 | 0.176 | 0.24 | 0.002 * | 0.65 † | 0.060 | 0.45 |

| SCL-90R Depression | 1.37 | 0.98 | 1.69 | 0.87 | 2.01 | 0.92 | 0.052 | 0.34 | 0.001 * | 0.68 † | 0.123 | 0.36 |

| SCL-90R Anxiety | 0.93 | 0.82 | 1.09 | 0.70 | 1.50 | 0.94 | 0.246 | 0.21 | 0.001 * | 0.65 † | 0.025 * | 0.50 † |

| SCL-90R Hostility | 0.77 | 0.87 | 1.18 | 1.00 | 1.14 | 0.83 | 0.011 * | 0.43 | 0.056 | 0.43 | 0.860 | 0.04 |

| SCL-90R Phobic anxiety | 0.46 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 0.71 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.646 | 0.08 | 0.005 * | 0.55 † | 0.023 * | 0.45 |

| SCL-90R Paranoia | 0.78 | 0.80 | 1.12 | 0.82 | 1.33 | 0.88 | 0.020 * | 0.41 | 0.002 * | 0.65 † | 0.245 | 0.25 |

| SCL-90R Psychotic | 0.81 | 0.76 | 1.05 | 0.74 | 1.30 | 0.91 | 0.070 | 0.33 | 0.003 * | 0.59 † | 0.155 | 0.30 |

| SCL-90R GSI | 0.96 | 0.74 | 1.19 | 0.68 | 1.51 | 0.78 | 0.073 | 0.32 | <0.001 * | 0.72 † | 0.052 | 0.44 |

| SCL-90R PST | 42.08 | 23.48 | 50.51 | 20.60 | 57.77 | 18.84 | 0.027 * | 0.38 | 0.001 * | 0.74 † | 0.140 | 0.37 |

| SCL-90R PSDI | 1.82 | 0.64 | 2.00 | 0.54 | 2.25 | 0.70 | 0.101 | 0.30 | 0.001 * | 0.64 † | 0.077 | 0.40 |

| UPPS-P Premeditation | 23.35 | 5.23 | 24.42 | 6.33 | 26.26 | 5.96 | 0.285 | 0.18 | 0.017 * | 0.52 † | 0.155 | 0.30 |

| UPPS-P Perseverance | 21.84 | 4.93 | 23.13 | 5.30 | 23.97 | 4.19 | 0.132 | 0.25 | 0.041 * | 0.47 | 0.449 | 0.18 |

| UPPS-P Sensation | 25.79 | 7.64 | 29.93 | 8.36 | 29.94 | 7.73 | 0.003 * | 0.52 † | 0.013 * | 0.54 † | 0.996 | 0.00 |

| UPPS-P Positive urgency | 28.96 | 7.79 | 32.60 | 10.67 | 34.39 | 9.69 | 0.023 * | 0.39 | 0.005 * | 0.62 † | 0.386 | 0.18 |

| UPPS-P Negative urgency | 30.06 | 6.55 | 32.76 | 8.00 | 34.97 | 5.61 | 0.025 * | 0.37 | 0.001 * | 0.81 † | 0.157 | 0.32 |

| UPPS-P Total | 129.4 | 21.40 | 142.8 | 24.15 | 149.6 | 21.03 | 0.001 * | 0.59 † | <0.001 * | 0.96 † | 0.175 | 0.30 |

| TCI-R Novelty seeking | 106.1 | 11.96 | 110.5 | 13.41 | 118.0 | 14.19 | 0.052 | 0.34 | <0.001 * | 0.91 † | 0.009 * | 0.55 † |

| TCI-R Harm avoidance | 101.7 | 18.91 | 100.0 | 17.36 | 104.3 | 13.20 | 0.577 | 0.09 | 0.487 | 0.16 | 0.281 | 0.28 |

| TCI-R Reward dependence | 99.1 | 13.47 | 96.1 | 14.76 | 95.0 | 10.46 | 0.196 | 0.21 | 0.150 | 0.34 | 0.727 | 0.08 |

| TCI-R Persistence | 103.7 | 19.38 | 106.1 | 17.27 | 111.0 | 16.83 | 0.463 | 0.13 | 0.061 | 0.40 | 0.233 | 0.29 |

| TCI-R Self-directedness | 134.2 | 20.26 | 123.9 | 22.10 | 116.4 | 20.34 | 0.005 * | 0.52 † | <0.0001 * | 0.88 † | 0.109 | 0.36 |

| TCI-R Cooperativeness | 132.4 | 16.46 | 129.7 | 16.68 | 124.1 | 14.83 | 0.335 | 0.16 | 0.017 * | 0.53 † | 0.132 | 0.35 |

| TCI-R Self-transcendence | 60.2 | 13.69 | 63.4 | 13.88 | 66.3 | 13.27 | 0.185 | 0.23 | 0.037 * | 0.45 | 0.348 | 0.21 |

| Illegal− (n = 85) | Illegal + Cons− (n = 55) | Illegal + Cons+ (n = 31) | Illegal + Co− vs. Illegal− | Illegal + Co+ vs. Illegal− | Illegal + Co+ vs. Illegal + Co− | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p | |φ| | p | |φ| | p | |φ| | |

| Any mental disorder | 16 | 18.8% | 18 | 32.7% | 6 | 19.4% | 0.061 | 0.158 † | 0.948 | 0.006 | 0.184 | 0.143 † |

| Depression | 5 | 5.9% | 4 | 7.3% | 1 | 3.2% | 0.743 | 0.028 | 0.568 | 0.053 | 0.441 | 0.083 |

| Anxiety | 4 | 4.7% | 4 | 7.3% | 1 | 3.2% | 0.553 | −0.050 | 0.289 | 0.098 | 0.450 | 0.081 |

| Bipolar | 3 | 3.5% | 1 | 1.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.523 | 0.054 | 0.728 | 0.032 | 0.441 | 0.083 |

| Other | 3 | 3.5% | 9 | 16.4% | 3 | 9.7% | 0.008 * | 0.224 † | 0.186 | 0.123 † | 0.390 | 0.093 |

| Any substance | 46 | 54.1% | 38 | 69.1% | 19 | 61.3% | 0.077 | 0.149 † | 0.491 | 0.064 | 0.463 | 0.079 |

| Tobacco | 41 | 48.2% | 35 | 63.6% | 16 | 51.6% | 0.074 | 0.151 † | 0.747 | 0.030 | 0.276 | 0.118 † |

| Alcohol | 11 | 12.9% | 6 | 10.9% | 5 | 16.1% | 0.719 | 0.030 | 0.659 | 0.041 | 0.486 | 0.075 |

| Illegal drugs | 1 | 1.2% | 8 | 14.5% | 5 | 16.1% | 0.002 * | 0.266 † | 0.001 * | 0.299 † | 0.844 | 0.021 |

| Illegal− (n = 85) | Illegal + Cons− (n = 55) | Illegal + Cons+ (n = 31) | Illegal + Co− vs. Illegal− | Illegal + Co+ vs. Illegal− | Illegal + Co+ vs. Illegal + Co− | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p | |φ| | p | |φ| | p | |φ| | ||

| Dropout | Present | 43 | 50.6% | 23 | 41.8% | 20 | 64.5% | 0.310 | 0.086 | 0.183 | 0.124 † | 0.043 * | 0.218 † |

| Absent | 42 | 49.4% | 32 | 58.2% | 11 | 35.5% | |||||||

| Relapses | Present | 19 | 22.4% | 17 | 30.9% | 10 | 32.3% | 0.258 | 0.096 | 0.276 | 0.101 † | 0.897 | 0.014 |

| Absent | 66 | 77.6% | 38 | 69.1% | 21 | 67.7% | |||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vintró-Alcaraz, C.; Mestre-Bach, G.; Granero, R.; Caravaca, E.; Gómez-Peña, M.; Moragas, L.; Baenas, I.; del Pino-Gutiérrez, A.; Valero-Solís, S.; Lara-Huallipe, M.; et al. Exploring the Association between Gambling-Related Offenses, Substance Use, Psychiatric Comorbidities, and Treatment Outcome. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4669. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11164669

Vintró-Alcaraz C, Mestre-Bach G, Granero R, Caravaca E, Gómez-Peña M, Moragas L, Baenas I, del Pino-Gutiérrez A, Valero-Solís S, Lara-Huallipe M, et al. Exploring the Association between Gambling-Related Offenses, Substance Use, Psychiatric Comorbidities, and Treatment Outcome. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(16):4669. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11164669

Chicago/Turabian StyleVintró-Alcaraz, Cristina, Gemma Mestre-Bach, Roser Granero, Elena Caravaca, Mónica Gómez-Peña, Laura Moragas, Isabel Baenas, Amparo del Pino-Gutiérrez, Susana Valero-Solís, Milagros Lara-Huallipe, and et al. 2022. "Exploring the Association between Gambling-Related Offenses, Substance Use, Psychiatric Comorbidities, and Treatment Outcome" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 16: 4669. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11164669

APA StyleVintró-Alcaraz, C., Mestre-Bach, G., Granero, R., Caravaca, E., Gómez-Peña, M., Moragas, L., Baenas, I., del Pino-Gutiérrez, A., Valero-Solís, S., Lara-Huallipe, M., Mora-Maltas, B., Valenciano-Mendoza, E., Guillen-Guzmán, E., Codina, E., Menchón, J. M., Fernández-Aranda, F., & Jiménez-Murcia, S. (2022). Exploring the Association between Gambling-Related Offenses, Substance Use, Psychiatric Comorbidities, and Treatment Outcome. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(16), 4669. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11164669