Defining the Impact of Social Drivers on Health Outcomes for People with Inherited Bleeding Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

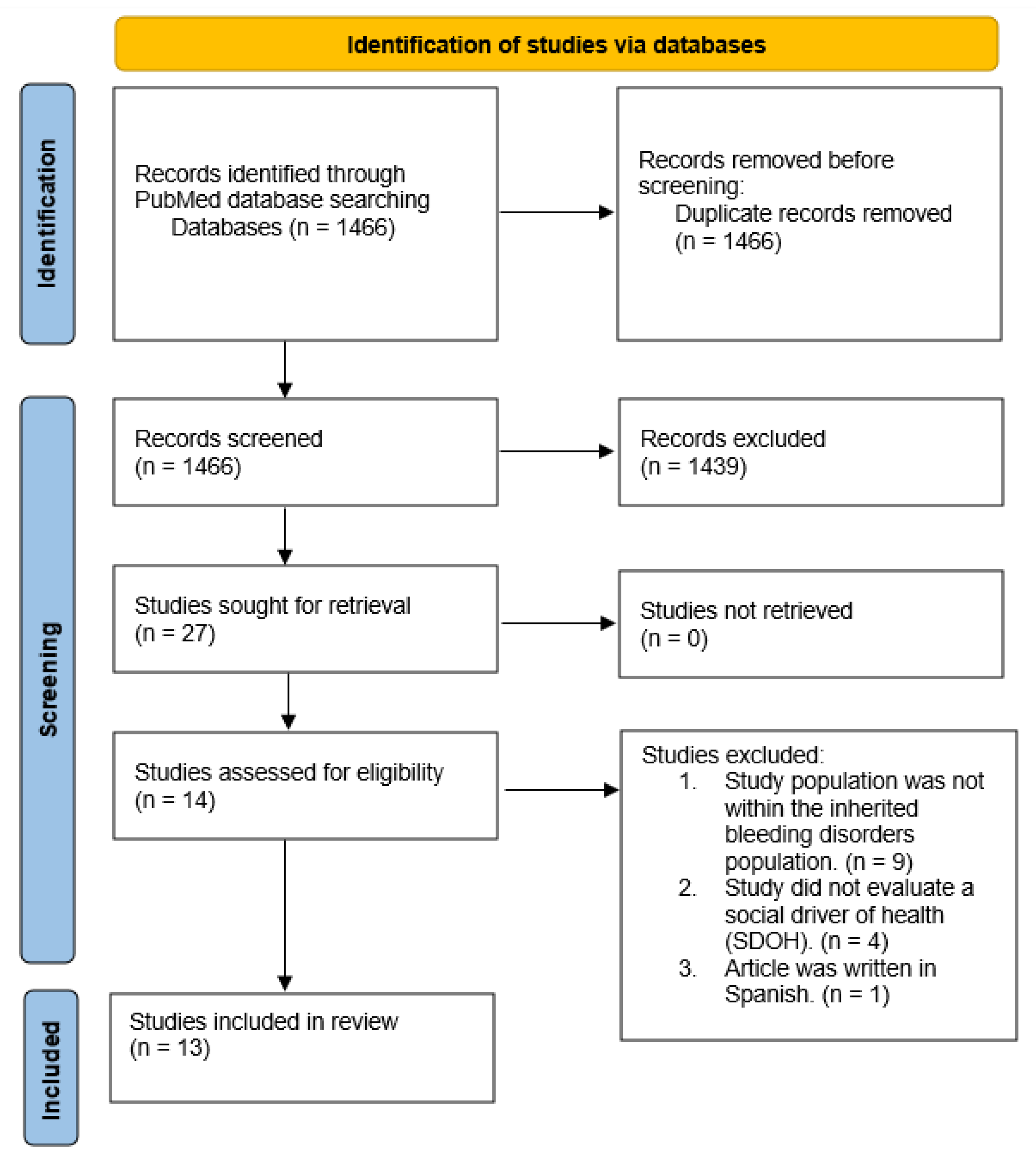

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Process

- Bleeding Frequency: The main clinical manifestation of a bleeding disorder is an increased bleeding tendency, either spontaneous or related injury, surgery, or physical trauma [8].

- Chronic Pain: Usually caused by arthritis in joints, a consequence of bleeds that have damaged the joint’s cartilage [12].

- Mortality: Inheritable bleeding disorders can lead to fatal complications if left untreated. Early detection and treatment can impact a person’s quality of life, thus impacting the SDOH [8].

- Cost: Considering that the total annual cost of treatment for many people with hemophilia is more than $250,000 per adult patient in the United States [16], cost can be an important consideration for the impact of the SDOH on PwIBDs.

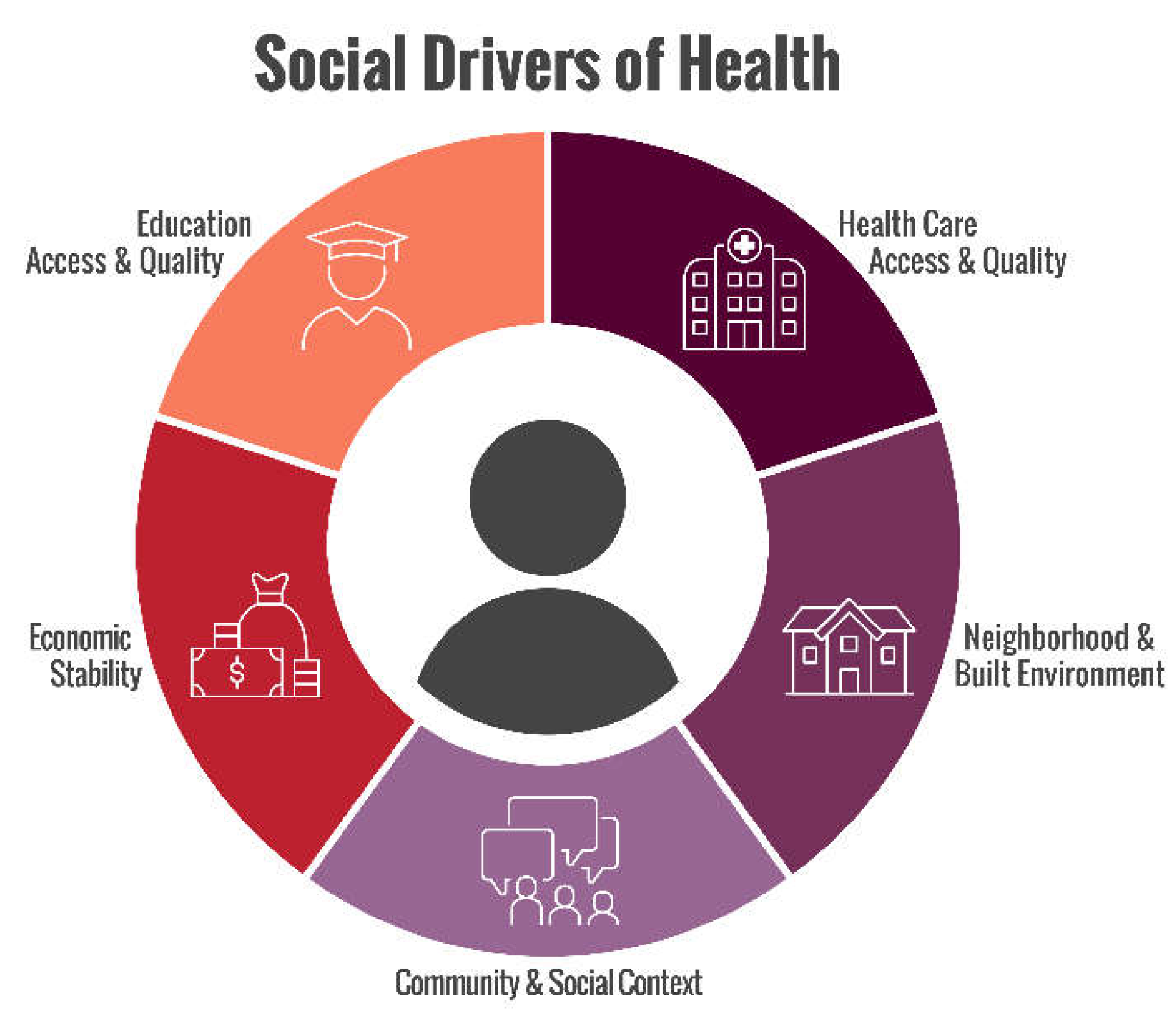

- Health Care System: access to healthcare and its quality (i.e., health insurance coverage and quality of care) [3].

- Economic Stability: finances (i.e., employment and income) [3]

- Neighborhood/physical environment: housing, environment (i.e., transportation, walkability, and safety) [3].

- Community/social context: ways a person lives, works, plays, and learns (i.e., social integration, support systems, and community engagement [3].

- Education: access to education and its quality (i.e., literacy and language) [3].

- Food: access to healthy/nutritious food (i.e., hunger) [3].

2.4. Data Collection Process and Study Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics and Outcomes of Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence by SDOH

4.2. Summary of Evidence by Clinical/Non-Clinical Health Outcome

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

7. Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Healthy People 2030. Social Determinants of Health. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Think Anthem. Social Drivers vs. Social Determinants of Health: Unstacking the Deck. 2022. Available online: https://www.thinkanthem.com/healthequity/social-drivers-vs-social-determinants-of-health-unstacking-the-deck/ (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Artiga, S.; Hinton, E. Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity. 2018. Available online: https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/ (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Arya, S.; Wilton, P.; Page, D.; Boma-Fischer, L.; Floros, G.; Dainty, K.N.; Winikoff, R.; Sholzberg, M. Healthcare provider perspectives on inequities in access to care for patients with inherited bleeding disorders. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill-Briggs, F.; Adler, N.E.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Chin, M.H.; Gary-Webb, T.L.; Navas-Acien, A.; Thornton, P.L.; Haire-Joshu, D. Social Determinants of Health and Diabetes: A Scientific Review. Diabetes Care 2020, 44, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreatsoulas, C.; Anand, S.S. The impact of social determinants on cardiovascular disease. Can. J. Cardiol. 2010, 26, 8C–13C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Personalized Hematology/Oncology of Wake Forest. Seeing Red: Bleeding Disorders Explained. Available online: https://www.hemoncnc.com/hematology/bleeding-disorders-explained (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Saxena, K. Barriers and perceived limitations to early treatment of hemophilia. J. Blood Med. 2013, 4, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The Voice of the Patient; FDA: Silver Spring, MA, USA, 2016.

- Thornton, R.L.J.; Glover, C.M.; Cené, C.W.; Glik, D.C.; Henderson, J.A.; Williams, D.R. Evaluating Strategies for Reducing Health Disparities by Addressing the Social Determinants of Health. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, J.M.; Lambing, A.; Witkop, M.L.; Anderson, T.L.; Munn, J.; Tortella, B. Racial Differences in Chronic Pain and Quality of Life among Adolescents and Young Adults with Moderate or Severe Hemophilia. J. Racial Ethn. Health Dispar. 2015, 3, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, T.W.; Bocharova, I.; Hagan, K.; Bensimon, A.G.; Yang, H.; Wu, E.Q.; Sawyer, E.K.; Li, N. Health care resource utilization and cost burden of hemophilia B in the United States. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 1954–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, T.; Asghar, S.; O’Hara, J.; Sawyer, E.K.; Li, N. Clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of severe hemophilia B in the United States: Results from the CHESS US and CHESS US+ population surveys. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Social Determinants of health-mesh NCBI: National Center for Biotechnology Information. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/?term=social%2Bdeterminants%2Bof%2Bhealth (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Okide, C.C.; Eseadi, C.; Koledoye, U.L.; Mbagwu, F.; Ekwealor, N.E.; Okeke, N.M.; Osilike, C.; Okeke, P.M. Challenges facing community-dwelling adults with hemophilia: Implications for community-based adult education and nursing. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 48, 300060519862101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, P.R.; Paredes, A.C.; Pedras, S.; Costa, P.; Crato, M.; Fernandes, S.; Lopes, M.; Carvalho, M.; Almeida, A. Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Psychosocial Characteristics of People with Hemophilia in Portugal: Findings from the First National Survey. TH Open 2018, 2, e54–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Atiq, F.; Mauser-Bunschoten, E.P.; Eikenboom, J.; Van Galen, K.P.M.; Meijer, K.; De Meris, J.; Cnossen, M.H.; Beckers, E.A.M.; Gorkom, B.A.P.L.-V.; Nieuwenhuizen, L.; et al. Sports participation and physical activity in patients with von Willebrand disease. Haemophilia 2018, 25, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, L.; Benson, G.; Lambert, J.; Benmedjahed, K.; Zak, M.; Lee, X.Y. Real-world utilities and health-related quality-of-life data in hemophilia patients in France and the United Kingdom. Patient Preference Adher. 2019, 13, 941–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, L.; Paroskie, A.; Gailani, D.; DeBaun, M.R.; Sidonio, R.F. Haemophilia A carriers experience reduced health-related quality of life. Haemophilia 2015, 21, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, M.; Takedani, H.; Yokota, K.; Haga, N. Strategies to encourage physical activity in patients with hemophilia to improve quality of life. J. Blood Med. 2016, 7, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govorov, I.; Ekelund, L.; Chaireti, R.; Elfvinge, P.; Holmström, M.; Bremme, K.; Mints, M. Heavy menstrual bleeding and health-associated quality of life in women with von Willebrand’s disease. Exp. Ther. Med. 2016, 11, 1923–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limperg, P.F.; Haverman, L.; Maurice-Stam, H.; Coppens, M.; Valk, C.; Kruip, M.J.H.A.; Eikenboom, J.; Peters, M.; Grootenhuis, M.A. Health-related quality of life, developmental milestones, and self-esteem in young adults with bleeding disorders. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 27, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauser-Bunschoten, E.P.; Kadir, R.A.; Laan, E.T.M.; Elfvinge, P.; Haverman, L.; Teela, L.; Degenaar, M.E.L.; van de Putte, D.E.F.; D’Oiron, R.; van Galen, K.P.M. Managing women-specific bleeding in inherited bleeding disorders: A multidisciplinary approach. Haemophilia 2020, 27, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, J.M.; Munn, J.E.; Anderson, T.L.; Lambing, A.; Tortella, B.; Witkop, M.L. Predictors of quality of life among adolescents and young adults with a bleeding disorder. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuner, B.; von Mackensen, S.; Holzhauer, S.; Funk, S.; Klamroth, R.; Kurnik, K.; Krümpel, A.; Halimeh, S.; Reinke, S.; Frühwald, M.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Hereditary Bleeding Disorders and in Children and Adolescents with Stroke: Cross-Sectional Comparison to Siblings and Peers. BioMed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 1579428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, L.A.; Baker, J.; Butler, R.; Escobar, M.; Frick, N.; Karp, S.; Koulianos, K.; Lattimore, S.; Nugent, D.; Pugliese, J.N.; et al. Integrated Hemophilia Patient Care via a National Network of Care Centers in the United States: A Model for Rare Coagulation Disorders. J. Blood Med. 2021, 12, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentino, L.A.; Blanchette, V.; Negrier, C.; O’Mahony, B.; Bias, V.; Sannié, T.; Skinner, M.W. Personalising haemophilia management with shared decision making. J. Haemoph. Prac. 2021, 8, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, R.L.; McCauley, L.A.; Koller, C.F. Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: A Report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. JAMA 2021, 325, 2437–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Search Number | Search Terms | Number of Articles Retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Blood Coagulation Disorders” [Mesh] OR “inherited bleeding disorder*” [tw] OR IBDs [tw], OR “bleeding disorder*” [tw] | 6441 |

| 2 | “Social Determinants of Health” [Mesh] OR “Social determinants of health*” [tw] OR SDOH [tw] OR “social determinant of health” [tw] | 10,114 |

| 3 | #1 AND access healthcare AND avail * healthcare AND access care AND avail * care | 12 |

| 4 | #1 AND “Geography” [Mesh] or “zip code*” [tw] | 3292 |

| 5 | #1 AND “Literacy” [Mesh] | 0 |

| 6 | #1 AND “ESL” [tw] AND “English Second Language*” [tw] | 0 |

| 7 | #1 AND “Cultural Competency” [Mesh] OR “cultural competence*” [tw] OR “cultural sensitivity *” [tw] | 3956 |

| 8 | #1 AND “Social Support” [Mesh] | 11 |

| 9 | #1 AND “Quality of Life” [Mesh] OR “QOL *” [tw] | 44,222 |

| 10 | #1 AND “Food Insecurity” [Mesh] OR food insecurity * | 5706 |

| 11 | #1 AND “Health Personnel” [Mesh] AND “quality” | 18 |

| 12 | #1 AND #2 | 10,114 |

| 13 | #1 AND #2-#12 | 6441 |

| 14 | #1 AND #13 Filters: Free full text, from 2011 - 2021 | 1466 |

| Author/Year | Title | Study Design | Objective | Number of Participants | Sample Population | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burke et al., 2021 [14] | Clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of severe hemophilia B in the United States: results from the CHESS US and CHESS US+ population surveys | Cross-sectional | Used the CHESS US and CHESS US+ data to analyze the clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of hemophilia B for patients treated with factor IX prophylaxis between 2017 and 2019 in the US. | 44 patient records in CHESS US and 57 patient records in CHESS US+ | Hemophilia B patients | Nearly all patients (85%) reported chronic pain, and the mean EQ-5D-5L utility value was 0.76 (0.24). The mean annual direct medical cost was $614,886, driven by factor IX treatment (mean annual cost, $611,971). Subgroup analyses showed mean annual costs of $397,491 and $788,491 for standard and extended half-life factor IX treatment, respectively. The mean annual non-medical direct costs and indirect costs of hemophilia B were $2371 and $6931. |

| Okide et al., 2020 [17] | Challenges facing community-dwelling adults with hemophilia: Implications for community-based adult education and nursing | Literature review | Discussed the challenges facing community-dwelling adults with hemophilia and the implications for community-based adult education and nursing. | Final number of articles reviewed were not disclosed | Community dwelling adults with hemophilia | Sustainable efforts are needed in the provision of local, national and international leadership and educational resources to improve and sustain health care for community-dwelling adults with hemophilia. |

| Pinto et al., 2018 [18] | Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Psychosocial Characteristics of People with Hemophilia in Portugal: Findings from the First National Survey | Cross-sectional | Describe sociodemographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics of PWH of all ages in Portugal | 146 males with hemophilia | 106 adults, 21 children/teenagers between 10 and 17 years, 11 children between 6 and 9 years, and 8 children between 1 and 5 years | High prevalence of joint deterioration and pain, with the ankles and the knees being the most affected joints among all age groups. A significant impact of hemophilia on professional and economic levels was particularly evident. Moreover, significant anxiety and depression symptoms were found on 36.7% and 27.2% of adults, respectively, and a belief of chronicity and symptoms unpredictability was particularly prominent among adults and children/teenagers. QoL was moderately affected among adults, but less affected in teenagers and children. |

| Author/Year | Title | Study Design | Objective | Number of Participants | Sample Population | Impact on Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arya et al., 2020 [5] | Healthcare provider perspectives on inequities in access to care for patients with inherited bleeding disorders | Cross-sectional | Understand healthcare provider perspectives regarding access to care and diagnostic delay amongst this patient population. | 70 respondents | Healthcare providers | Rural location was felt to be a significant contributor to both delayed diagnosis and decreased access to care. Such results are supported by our group’s presently ongoing qualitative interviews with patients with bleeding disorders, in which geographical barriers are a recurrent theme. |

| Author/Year | Title | Study Design | SDOH Evaluated | Objective | Number of Participants | Sample Population | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okide et al., 2020 [17] | Challenges facing community-dwelling adults with hemophilia: Implications for community-based adult education and nursing | Literature review | 1.Education 2. Health care system 3. Economic stability 4. Community, Safety, and Social Context | Discussed the challenges facing community-dwelling adults with hemophilia and the implications for community-based adult education and nursing. | Final number of articles reviewed were not disclosed | Community dwelling adults with hemophilia | Sustainable efforts are needed in the provision of local, national and international leadership and educational resources to improve and sustain health care for community-dwelling adults with hemophilia. |

| Pinto et al., 2018 [18] | Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Psychosocial Characteristics of People with Hemophilia in Portugal: Findings from the First National Survey | Cross-sectional | 1. Neighborhood and Physical Environment 2. Community, Safety, and Social Context 3. Education 4. Health care System 5. Economic Stability | Describe sociodemographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics of PWH of all ages in Portugal | 146 males with hemophilia | 106 adults, 21 children/teenagers between 10 and 17 years, 11 children between 6 and 9 years, and 8 children between 1 and 5 years | High prevalence of joint deterioration and pain, with the ankles and the knees being the most affected joints among all age groups. A significant impact of hemophilia on professional and economic levels was particularly evident.Moreover, significant anxiety and depression symptoms were found on 36.7% and 27.2% of adults, respectively, and a belief of chronicity and symptoms unpredictability was particularly prominent among adults and children/teenagers. QoL was moderately affected among adults, but less affected in teenagers and children. |

| Author/Year | Title | Study Design | Objective | Number of Participants | Sample Population | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atiq et al., 2018 [19] | Sports participation and physical activity in patients with von Willebrand disease | Cross-sectional | Assessed the sports participation and physical activity of a large cohort of VWD patients. | 798 VWD patients | 474 had type 1, 301 type 2 and 23 type 3 VWD. The mean age was 39 ± 20 (standard deviation) years | Type 3 VWD patients more often did not participate in sports due to fear of bleeding and physical impair- ment, respectively, OR = 13.24 (95% CI: 2.45–71.53) and OR = 5.90 (95% CI: 1.77–19.72). Patients who did not participate in sports due to physical impairment had a higher bleeding score item for joint bleeds 1.0 (±1.6) vs 0.5 (±1.1) (p = 0.036). Patients with type 3 VWD and patients with a higher bleeding score frequently had severe limitations during daily activities, respectively, OR = 9.84 (95% CI: 2.83–34.24) and OR = 1.08 (95% CI: 1.04–1.12). |

| Okide et al., 2020 [17] | Challenges facing community-dwelling adults with hemophilia: Implications for community-based adult education and nursing | Literature review | Discussed the challenges facing community-dwelling adults with hemophilia and the implications for community-based adult education and nursing. | Final number of articles reviewed were not disclosed | Community dwelling adults with hemophilia | Sustainable efforts are needed in the provision of local, national and international leadership and educational resources to improve and sustain health care for community-dwelling adults with hemophilia. |

| Pinto et al., 2018 [18] | Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Psychosocial Characteristics of People with Hemophilia in Portugal: Findings from the First National Survey | Cross-sectional | Describe sociodemographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics of PWH of all ages in Portugal | 146 males with hemophilia | 106 adults, 21 children/teenagers between 10 and 17 years, 11 children between 6 and 9 years, and 8 children between 1 and 5 years | High prevalence of joint deterioration and pain, with the ankles and the knees being the most affected joints among all age groups. A significant impact of hemophilia on professional and economic levels was particularly evident. Moreover, significant anxiety and depression symptoms were found on 36.7% and 27.2% of adults, respectively, and a belief of chronicity and symptoms unpredictability was particularly prominent among adults and children/teenagers. QoL was moderately affected among adults, but less affected in teenagers and children. |

| Burke et al., 2021 [14] | Clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of severe hemophilia B in the United States: results from the CHESS US and CHESS US+ population surveys | Cross-sectional | Used the CHESS US and CHESS US+ data to analyze the clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of hemophilia B for patients treated with factor IX prophylaxis between 2017 and 2019 in the US. | 44 patient records in CHESS US and 57 patient records in CHESS US+ | Hemophilia B patients | Nearly all patients (85%) reported chronic pain, and the mean EQ-5D-5L utility value was 0.76 (0.24). The mean annual direct medical cost was $614,886, driven by factor IX treatment (mean annual cost, $611,971). Subgroup analyses showed mean annual costs of $397,491 and $788,491 for standard and extended half-life factor IX treatment, respectively. The mean annual non-medical direct costs and indirect costs of hemophilia B were $2371 and $6931. |

| Carroll et al., 2019 [20] | Real-world utilities and health-related quality-oflife data in hemophilia patients in France and the United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | Collect health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) and health-utility data from hemophilia patients with differing disease severity | 122 patients in France and 62 in the UK = 184 participants | Patients with hemophilia aged ≥12 years | The collected utility values reflected real-world data and can potentially serve as health-state weights in future cost–utility analyses, although it is important not to use EQ-5D-3L-, EQ-5D-5L-, and SF-6D-derived utility values interchangeably. The HRQoL data further documented the physical burden linked to hemophilia and its complications. |

| Gilbert et al., 2015 [21] | Haemophilia A Carriers Experience Reduced Health-Related Quality of Life | Cross-sectional | Test the hypothesis that haemophilia A carriers have reduced HR-QOL related to bleeding symptoms. | 42 haemophilia A carriers and 36 control subjects = 78 | Case subjects were obligated or genetically verified haemophilia A carriers age 18 to 60 years. Control subjects were mothers of children with cancer who receive care at the Vanderbilt pediatric hematology-oncology clinic. | Haemophilia A carriers had significantly lower median scores for the domains of “Pain” (73.75 versus 90; p = 0.02) and “General health” (75 versus 85; p = 0.01) compared to control subjects. Such findings highlight the need for further investigation of the effect of bleeding on HR-QOL in this population. |

| Goto et al., 2016 [22] | Strategies to encourage physical activity in patients with hemophilia to improve quality of life | Literature review | Discuss strategies to encourage physical activity (PA) through a behavior change approach by focusing on factors relevant to hemophilia, such as benefits and bleeding risk of PA, risk management of bleeding, PA characteristics, and difficulty with exercise adherence. | 14 articles reviewed | Patients with hemophilia | For patients who find it difficult to participate in PA, it is necessary to plan individual behavior change approaches and encourage improvement in self-efficacy. |

| Govorov et al., 2015 [23] | Heavy menstrual bleeding and health-associated quality of life in women with von Willebrand’s disease | Cross-sectional | Investigate whether women with VWD experienced heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) and an impaired health-associated quality of life. | 30 women | Women with VWD | Of the 30 women (18–52 years) that were included in the present study, 50% suffered from HMB, although the majority received treatment for HMB. In addition, almost all the included women perceived limitations in the overall life activities due to menstruation. The health-associated quality of life for women with HMB was significantly lower (p < 0.10) with regards to ‘bodily pain’ compared with Swedish women of the general population. |

| Limperg et al., 2018 [24] | Health-related quality of life, developmental milestones, and selfesteem in young adults with bleeding disorders | Cross-sectional | Assessed HRQOL, developmental milestones, and self-esteem in Dutch young adults (YA) with bleeding disorders compared to peers. | 112 YA | Ninety-five YA (18–30 years) with bleeding disorders (78 men; mean 24.7 years, SD 3.5) and 17 women (mean 25.1 years, SD 3.8) | This study demonstrates that YA men with bleeding disorders show slight impairments in total HRQOL, physical functioning, school/work functioning (PedsQL_YA), and self-esteem (RSES), in comparison to their (healthy, sex-matched) peers. |

| Mauser-Bunschoten et al., 2021 [25] | Managing women-specific bleeding in inherited bleeding disorders: A multidisciplinary approach | Case study | To support appropriate multidisciplinary care for WBD in haemophilia treatment centers. | Two cases | Women and girls with bleeding disorders | Multidisciplinary management is important to preserve quality of life and social participation for women from menarche onwards. |

| McLaughlin et al., 2017 [26] | Predictors of quality of life among adolescents and young adults with a bleeding disorder | Cross-sectional | Describe factors related to HRQoL in adolescents and young adults with hemophilia A or B or von Willebrand disease. | 108 respondents | Volunteers aged 13 to 25 years with hemophilia or von Willebrand disease | Efforts should be made to prevent and manage chronic pain, which was strongly related to physical and mental HRQoL, in adolescents and young adults with hemophilia and von Willebrand disease. |

| Neuner et al., 2016 [27] | Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Hereditary Bleeding Disorders and in Children and Adolescents with Stroke: Cross-Sectional Comparison to Siblings and Peers | Cross-sectional | Compare self-reported measures of HrQoL in a group of children and adolescents with a chronic medical condition, but no expected functional restrictions, hereditary bleeding disorder (HBD), to their siblings and peers. | 144 patients | 74 were patients with HBD (51.4%) and 70 were patients with stroke or TIA (48.6%) | The most relevant finding in this investigation was the overall good health-related quality of life (HrQoL)—as measured with a generic instrument, the KINDL-R questionnaire—in children with hereditary bleeding disorders |

| Author/Year | Title | Study Design | Objective | Number of Participants | Sample Population | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arya et al., 2020 [5] | Healthcare provider perspectives on inequities in access to care for patients with inherited bleeding disorders | Cross-sectional | Understand healthcare provider perspectives regarding access to care and diagnostic delay amongst this patient population. | 70 respondents | Healthcare providers | HCPs felt that there were diagnostic delays for patients with mild symptomatology (71%, N = 50), women presenting with abnormal uterine bleeding as their only or primary symptom (59%, N = 41), and patients living in rural Canada (50%, N = 35). Fewer respondents felt that factors such as socioeconomic status (46%, N = 32) or race (21%, N = 15) influenced access to care, particularly as compared to the influence of rural location (77%, N = 54). |

| Burke et al., 2021 [14] | Clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of severe hemophilia B in the United States: results from the CHESS US and CHESS US+ population surveys | Cross-sectional | Used the CHESS US and CHESS US+ data to analyze the clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of hemophilia B for patients treated with factor IX prophylaxis between 2017 and 2019 in the US. | 44 patient records in CHESS US and 57 patient records in CHESS US+ | Hemophilia B patients | Nearly all patients (85%) reported chronic pain, and the mean EQ-5D-5L utility value was 0.76 (0.24). The mean annual direct medical cost was $614,886, driven by factor IX treatment (mean annual cost, $611,971). Subgroup analyses showed mean annual costs of $397,491 and $788,491 for standard and extended half-life factor IX treatment, respectively. The mean annual non-medical direct costs and indirect costs of hemophilia B were $2371 and $6931. |

| Okide et al., 2020 [17] | Challenges facing community-dwelling adults with hemophilia: Implications for community-based adult education and nursing | Literature review | Discussed the challenges facing community-dwelling adults with hemophilia and the implications for community-based adult education and nursing. | Final number of articles reviewed were not disclosed | Community dwelling adults with hemophilia | Sustainable efforts are needed in the provision of local, national and international leadership and educational resources to improve and sustain health care for community-dwelling adults with hemophilia. |

| Pinto et al., 2018 [18] | Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Psychosocial Characteristics of People with Hemophilia in Portugal: Findings from the First National Survey | Cross-sectional | Describe sociodemographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics of PWH of all ages in Portugal | 146 males with hemophilia | 106 adults, 21 children/teenagers between 10 and 17 years, 11 children between 6 and 9 years, and 8 children between 1 and 5 years | High prevalence of joint deterioration and pain, with the ankles and the knees being the most affected joints among all age groups. A significant impact of hemophilia on professional and economic levels was particularly evident. Moreover, significant anxiety and depression symptoms were found on 36.7% and 27.2% of adults, respectively, and a belief of chronicity and symptoms unpredictability was particularly prominent among adults and children/teenagers. QoL was moderately affected among adults, but less affected in teenagers and children. |

| Study Author, Year | Bleed Frequency | Chronic Pain | Mortality | Cost | Quality of Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Stability | |||||

| Burke et al., 2021 [14] | The mean annual bleed rate (ABR) from CHESS US was 1.73 (SD 1.39; median 2.0; Table 2). At least one bleed-related hospitalization was reported by 9.1% of CHESS US patients in the previous year, with a mean length of stay of 0.3 days. | The mean reported EQ-5D-5L score was 0.74 (SD 0.26). More than one-quarter (28%) of patients from CHESS US+ reported chronic pain ratings ≥ 6/10, and half (56%) reported pain 1–5/10 on average over the past year. | Total annual direct medical costs of hemophilia B from CHESS US were $614,886, driven almost entirely by the cost of FIX treatment ($611,971). The annual direct medical cost of hemophilia B excluding FIX treatment was $2885. | Hemophilia B is known to cause substantial functional limitations and reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL). | |

| Okide et al., 2020 [17] | Many community-dwelling adults with hemophilia may choose to work in jobs that are unsuitable for them, so as to obtain or maintain insurance coverage. At the same time, many with insurance coverage face rising costs of co-payments and lifetime restrictions. In addition to uncertainty about their ability to keep working, health insurance concerns can be distressing to people with hemophilia and their families. | ||||

| Pinto et al., 2018 [18] | The occurrence of bleeding episodes in the previous year was reported by 71 (67%) adults, 15 (71.4%) children /teenagers, and 6 (54.5%) and 4 (50%) young children, with the mean number of bleeding episodes varying from 4.53 (SD = 3.36) in the group of children/teenagers to 14.94 (SD = 16.90) among adults. | Pain was reported by a vast majority of participants of all age groups (>18 years: 82 [77.4%]; 10–17 years: 16 [76.2%]; 6–9 years: 9 [81.8%]; 1–5 years: 4 [50%]). Pain in the lower limbs was considered to have the greatest impact, namely, in the ankles (>18 years: 31 [37.8%]; 10–17 years: 7 [43.9%]; 6–9 years: 5 [55.5%]; 1–5 years: 1 [25%]). Pain showed a wide duration range, varying from 1 month in three age groups to 612 months (51 years) in the adults group. | A36 Hemofilia-QoL global mean score was 96.45 (SD = 27.33), with subscale scores for each specific domain also being reported. Considering CHO-KLAT, mean scores were 75.63 (SD = 12.06) for the 10 to 17 years old group and 76.32 (SD = 11.89) for the 6 to 9 years old group. | ||

| Neighborhood and Physical Environment | |||||

| Arya et al., 2020 [5] | With regards to which factors might affect care received by women with inherited bleeding disorders, the majority of respondents felt that lack of patient awareness around “normal” versus “abnormal bleeding” (90%, N = 63) and lack of HCP awareness (73%, N = 51) were the main barriers to care. For almost all respondents (71%, N = 49), symptoms of excessive bleeding were the most common reason for referral, followed by a positive family history (14%, N = 10) and abnormalities seen on routine bloodwork (13%, N = 9) | When asked how satisfied they thought their patients were with their quality of life, 3% of respondents (N = 2) felt that their patients were very satisfied, 58% (N = 40) felt they were satisfied, 20% (N = 14) felt they were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 1.5% (N = 1) felt they were dissatisfied, and none felt that they were very dissatisfied. Seventeen percent (N = 12) were uncertain. With regards to how long they estimated their patients’ travel time to clinic appointments to be, approximately half (48%, N = 34) estimated 30 minutes to one hour; 33% (N = 23) indicated one hour to two hours, 11% (N = 8) estimated over two hours, and a minority (6%, N = 4) said it took less than 30 minutes. When then asked whether they thought that access to a multidisciplinary clinic could improve quality of care for women with inherited bleeding disorders, the vast majority (90%, N = 63) indicated yes; one respondent (1.5%) indicated no, and 6 respondents (8%) were unsure. | |||

| Education | |||||

| Okide et al., 2020 [17] | See health outcome summary above | ||||

| Pinto et al., 2018 [18] | See health outcome summary above | See health outcome summary above | See healh outcome summary above | ||

| Community and Social Context | |||||

| Atiq et al., 2018 [19] | Patients who participated in sports had a higher bleeding score item for muscle haematoma 0.38 ± 0.95 vs 0.24 ± 0.75 (p = 0.023), which remained significant after correction for age and sex (OR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.04-1.53). | Authors found a linear association between more hours of physical activity per week and a better general health status (p < 0.001). | |||

| Okide et al., 2020 [17] | See healh outcome summary above | ||||

| Pinto et al., 2018 [18] | See health outcome summary above | See health outcome summary above | See healh outcome summary above | ||

| Burke et al., 2021 [14] | See health outcome summary above | See health outcome summary above | See health outcome summary above | See healh outcome summary above | |

| Carroll et al., 2019 [20] | Participants reporting a higher frequency of joint pain and history of joint surgery had statistically significantly lower EQ-5D-3L utility values than participants who did not experience joint pain or who had not had joint surgery previously (p < 0.001). | Participants with a history of long hospital stays due to hemophilia reported significantly lower SF-36 PCS scores (p = 0.002) than those without such a history. Also, patients with more frequent visits to medical professionals regarding hemophilia reported significantly lower SF-36 PCS scores (p = 0.004) than those with less frequent visits. In contrast, no significant differences were found for SF-36 MCS scores. | |||

| Gilbert et al., 2015 [21] | Haemophilia A carriers reported more severe bleeding symptoms than control subjects. The median Tosetto bleeding score of haemophilia A carriers was significantly higher than for women in the control arm (5 versus 1; p < 0.001). Also, haemophilia A carriers reported greater menstrual blood loss than controls as indicated by a significantly higher median pictorial blood assessment chart score (423 versus 182.5; p = 0.01). | Haemophilia A carriers had significantly lower scores in the “Pain” and “General Health” domains of the Rand 36-item Health Survey 1.0 than controls. Haemophilia A carriers had a median “Pain” score of 73.75 compared to a median score of 90 for control subjects (p = 0.02). | Our analysis indicates that haemophilia A carriers tend to have poorer HR-QOL than women who are not haemophilia A carriers, particularly in the areas of pain and general health. | ||

| Goto et al., 2016 [22] | Physical activity (PA) level has been positively correlated with bleeding risk among patients with severe and moderate hemophilia. In addition, significant differences were found in the prevalence of bleeding events, as those who exercised strenuously were more likely to incur bleeds due to trauma, and 55% of PWH actively engaged in sports reported bleeding episodes associated with PA. On the other hand, there was no significant correlation between PA level and bleeding frequency of target joints or joint function, suggesting that the risk of bleeding is dependent on bleeding history, hemostatic control, and sport participation. | Physical inactivity is the fourth leading risk factor for mortality, accounting for 6% fo deaths globally. | Continuous PA, rather than the type of exercise, is an important determinant of health-related quality of life, even for people with hemophilia. | ||

| Govorov et al., 2015 [23] | In the study population, 66.7% of the women with VWD type 1 reported HMB compared with 36.4% of the women with VWD type 2 and 25.0% of the women with VWD type 3. | In the dimension of bodily pain, the group of women with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) had significantly lower scores compared with those of women in the general Swedish population. This implies that the women in the study population with HMB experienced an impaired health-associated quality of life due to pain. | The health-associated quality of life according to SF-36 appeared to be lower in the study population compared with Swedish women in the general population. However, the differences in median SF-36 scores were not statistically significant. | ||

| Limperg et al., 2018 [24] | YA men with severe hemophilia (median 81.25, mean 78.86, SD 19.39) reported lower physical functioning than men with non-severe hemophilia (median 93.75, mean 93.06, SD 7.21, p < 0.01, r = 0.45) on the PedsQL_YA. HRQOL scores did not differ on the other PedsQL_YA scales between severity groups. | ||||

| Mauser-Bunschoten et al., 2021 [25] | HMB and post-partum haemorrhages are the most frequent bleeding episodes seen associated with lower quality of life and iron deficiency anaemia. | The health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in 13 years old girls with a bleeding disorder is lower compared to their healthy peers. In contrast, there is no apparent difference in psychosocial functioning and HRQoL between young adult women with a bleeding disorder compared to peers. | |||

| McLaughlin et al., 2017 [26] | Compared with patients with no to mild chronic pain, those with moderate to severe chronic pain had 25.5-point (95% CI: 17.2, 33.8; p < 0.001) and 10.0-point (95% CI: 0.8, 19.2; p = 0.03) reductions in median PCS and MCS, respectively. | Adolescent and young adult (AYA) females with a bleeding disorder reported lower physical HRQoL when compared with AYA men in this study, even after adjustment for other sociodemographic and clinical factors. | |||

| Neuner et al., 2016 [27] | Multivariate analyses within patients, siblings, and peers revealed no differences in self-reported overall wellbeing and all KINDL-R subdimensions in group 1 (see Figure 1; all p > 0.05). In group 2, differences occurred inmultivariate analyses in self-reported overall wellbeing and all subdimensions (overall wellbeing p < 0.001, physical wellbeing p = 0.016, emotional wellbeing p = 0.007, self-worth p = 0.046, family relatedwellbeing p = 0.010, friend-related wellbeing p < 0.001, and school-related wellbeing p = 0.003). | ||||

| Health Care System | |||||

| Arya et al., 2020 [5] | See health outcome summary above | See health outcome summary above | |||

| Burke et al., 2021 [14] | See health outcome summary above | See health outcome summary above | See health outcome summary above | See health outcome summary above | |

| Okide et al., 2020 [17] | See health outcome summary above | ||||

| Pinto et al., 2018 [18] | See health outcome summary above | See health outcome summary above | See health outcome summary above | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopez, K.; Norris, K.; Hardy, M.; Valentino, L.A. Defining the Impact of Social Drivers on Health Outcomes for People with Inherited Bleeding Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4443. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11154443

Lopez K, Norris K, Hardy M, Valentino LA. Defining the Impact of Social Drivers on Health Outcomes for People with Inherited Bleeding Disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(15):4443. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11154443

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopez, Karina, Keri Norris, Marci Hardy, and Leonard A. Valentino. 2022. "Defining the Impact of Social Drivers on Health Outcomes for People with Inherited Bleeding Disorders" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 15: 4443. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11154443

APA StyleLopez, K., Norris, K., Hardy, M., & Valentino, L. A. (2022). Defining the Impact of Social Drivers on Health Outcomes for People with Inherited Bleeding Disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(15), 4443. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11154443