Parents’ Perspectives on Counseling for Fetal Heart Disease: What Matters Most?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Sample Structure and Counseling Success

3.2. Multiple Linear Regression

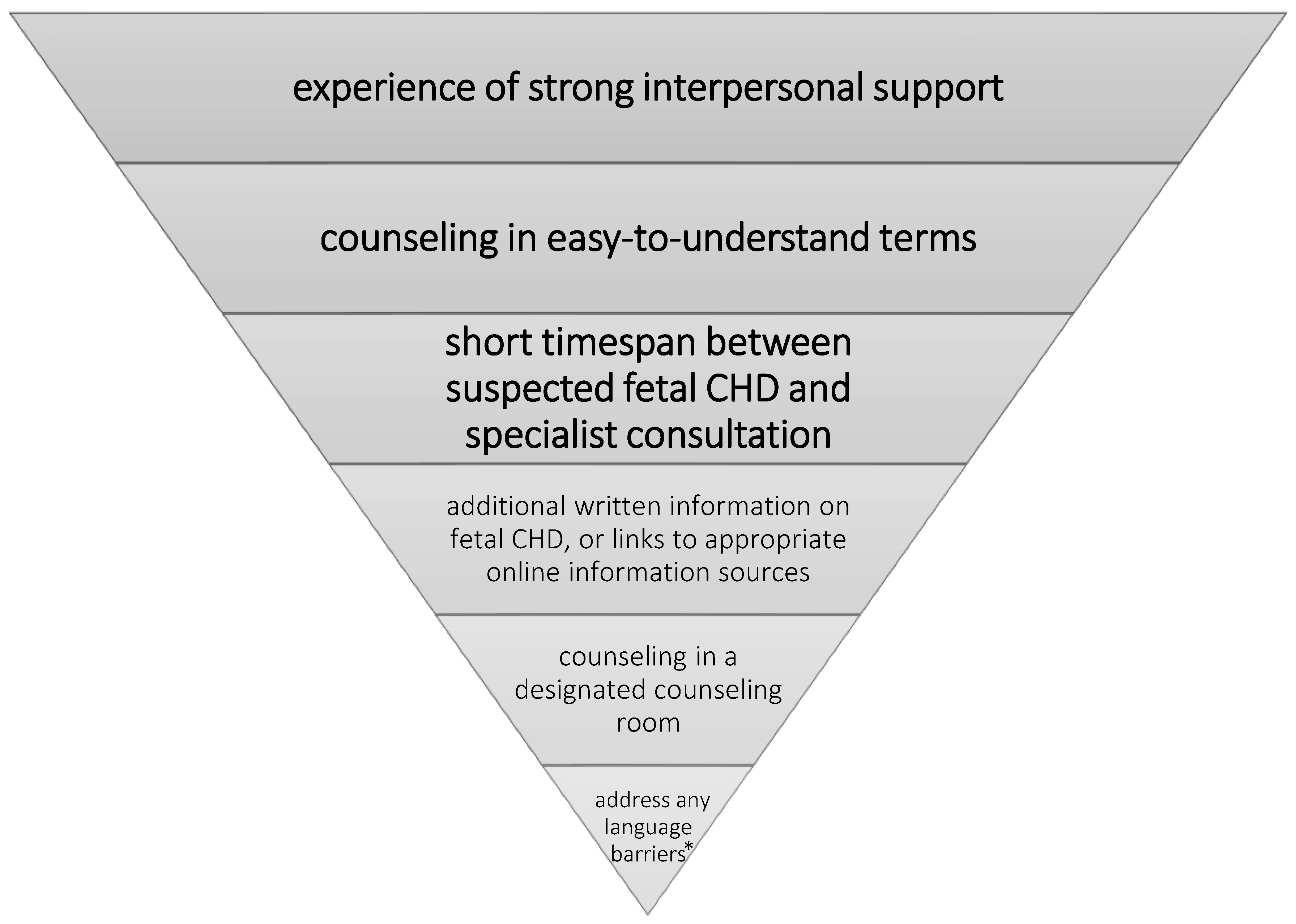

3.2.1. Overall Counseling Success

- “Little time was lost between a potential cardiac diagnosis and the proper counseling after making the correct diagnosis by a specialist” (temporal aspect); β = 0.135 **, p = 0.006.

- “During the conversation, the topic was explained to me in an easy and understandable way (for example, without technical terms or phrases)” (social aspect); β = 0.249 ***, p = 0.000.

- “I experienced strong support from the physician who conducted the conversation” (social aspect); β = 0.616 ***, p = 0.000.

- The location of the treatment center β = 0.102 *, p = 0.037.

3.2.2. Effects on Subdimensions

Social Factors

Spatiotemporal Factors

Informational Factors

Control Variables

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Expression | Valid % * |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 59.3 |

| Male | 40.7 | |

| Age | Mean value (years) | 34.63 |

| Median (years) | 35 | |

| SD | 5.404 | |

| Permanent relationship | Yes | 90.3 |

| No | 9.7 | |

| ISCED ** | Low | 6.2 |

| Medium | 38.2 | |

| High | 55.6 | |

| Social status *** | Low | 27.6 |

| Medium | 43.3 | |

| High | 29.0 | |

| German first language | Yes | 83.2 |

| No | 16.8 | |

| Preexisting medical knowledge | Yes | 31.1 |

| No | 68.9 | |

| Sorrows **** | Major sorrows | 35.8 |

| Intermediate sorrows | 25.0 | |

| Low sorrows | 39.3 | |

| Location | Location A: centers 1 + 2 | 35.8 |

| Location B: centers 3 + 4 | 64.2 | |

| Counseling during the COVID-19-pandemic | Yes | 25.2 |

| No | 74.8 | |

| Gestational age at fetal cardiac diagnosis | Mean value (weeks + days) | 24 + 1 |

| Median (weeks + days) | 23 | |

| Minimum (weeks + days) | 9 | |

| Maximum (weeks + days) | 38 | |

| SD (weeks + days) | 6+1 | |

| Severity of fetal CHD ***** | Low | 11.6 |

| Medium | 31.3 | |

| High | 57.1 |

| Fetal Cardiac Diagnosis | Genetic or Extra-Cardiac Findings | Number of Cases |

|---|---|---|

| AVSD | Trisomy 21 | 6 |

| AVSD | 5 | |

| AVSD, ARSA | Trisomy 21 | 1 |

| AVSD, hypoplastic aortic arch, coarctation | 1 | |

| AVSD, TOF | Trisomy 21 | 1 |

| Coarctation | 5 | |

| Coarctation | Turner syndrome | 1 |

| Coarctation, ARSA | 1 | |

| Suspicion for coarctation, ventricular disproportion | 2 | |

| Coarctation, aortic stenosis | 1 | |

| Critical aortic stenosis | 2 | |

| Critical aortic stenosis, severe mitral regurgitation, coarctation | 1 | |

| Aortic stenosis, aortic arch hypoplasia, Perimembranous VSD | 1 | |

| Borderline left ventricle, hypoplastic aortic arch, coarctation, LSVC | 1 | |

| Critical pulmonary stenosis, severe tricuspid regurgitation | 1 | |

| Severe pulmonary stenosis, severe tricuspid regurgitation | 1 | |

| DILV, MGA, aortic arch hypoplasia | 1 | |

| DILV, MGA, aortic arch hypoplasia, bilateral SVC | 1 | |

| DORV | 4 | |

| DORV, aortic arch hypoplasia, coarctation | 1 | |

| DORV, MGA, right aortic arch, hypoplastic aortic arch, coarctation | 1 | |

| DORV, subpulmonary stenosis | 1 | |

| DORV, TGA | 1 | |

| DORV, TGA, PA | 1 | |

| DORV, TGA, subpulmonary stenosis | 1 | |

| DORV, TOF type, right aortic arch, MAPCA | 1 | |

| Severe Ebstein´s anomaly of the tricuspid valve | 1 | |

| Ebstein´s anomaly of the tricuspid valve | 2 | |

| Heterotaxy syndrome, AVSD, absent right AV connection, pulmonary stenosis, MGA, bilateral SVCs | Situs inversus abdominalis, asplenia | 1 |

| Heterotaxy syndrome, AVSD, pulmonary stenosis, MGA, right aortic arch | 1 | |

| Heterotaxy syndrome, dextrocardia, DORV, pulmonary stenosis, MGA | 1 | |

| Heterotaxy syndrome, HLHS, TAPVR, azygos continuation | 1 | |

| HLHS | 8 | |

| HLHS, DORV | 1 | |

| HLHS, VSD | 1 | |

| Hypoplastic aortic arch | 2 | |

| Hypoplastic aortic arch, borderline LV | 1 | |

| Hypoplastic aortic arch, coarctation | 2 | |

| Hypoplastic aortic arch, perimembranous VSD | 1 | |

| Hypoplastic aortic arch, VSD | * MCAD | 1 |

| Hypoplastic aortic arch, VSD muscular, PAPVR | 1 | |

| IAA, borderline left ventricle | DiGeorge-syndrome | 1 |

| IAA, VSD | 1 | |

| LAI, dextrocardia, hypoplastic right ventricle, tricuspid atresia, pulmonary stenosis, VSD, MGA | 1 | |

| LSVC | 1 | |

| LSVC, * ASD | Trisomy 21 | 1 |

| * ASD | Trisomy 21 | 1 |

| Mild tricuspid regurgitation | 1 | |

| Non-compaction cardiomyopathy | 1 | |

| PA, IVS | 2 | |

| PA, IVS, sinusoids | 1 | |

| PA, VSD | 4 | |

| PA, VSD, MAPCAs | 1 | |

| PA, VSD, TGA | 1 | |

| PA/IVS, bipartite right ventricle, right ventricular hypertrophy | 1 | |

| Pulmonary stenosis | 1 | |

| Right aortic arch | 1 | |

| TGA (complex) | 10 | |

| TGA (simple) | 8 | |

| ccTGA | 2 | |

| TOF | Trisomy 21 | 1 |

| TOF | 6 | |

| TOF, right aortic arch | DiGeorge-syndrome | 1 |

| Tricuspid atresia | 2 | |

| Tricuspid atresia Ib | 1 | |

| Tricuspid valve dysplasia, moderate regurgitation, mild pulmonary stenosis, LSVC | Trisomy 21 | 1 |

| Tricuspid valve dysplasia, prenatal duct closure | 1 | |

| VSD | renal agenesis | 1 |

| VSD | 4 | |

| VSD | * Reciprocal translocation chromosome 1 and 7; deletions: 1q43 and 7p15.3–p21.1 | 1 |

| VSD | * Cystic fibrosis | 1 |

| VSD, hypoplastic aortic arch, coarctation, LSVC | 1 | |

| VSD, inlet | 1 | |

| VSD, muscular | 1 | |

| VSD, perimembranous | 1 |

| Counseling Success: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Successful * | Satisfying * | Unsuccessful * | |

| (a) Overall counseling success: | 47.5% | 52% | 0.5% |

| (b) Subdimensions: | |||

| Transfer of medical knowledge | 49.1% | 49.5% | 1.4% |

| Trust in medical staff | 72.8% | 24.4% | 2.8% |

| Transparency regarding the treatment process | 63.8% | 35.3% | 0.9% |

| Coping resources | 50.5% | 45.0% | 4.6% |

| Perceived situational control | 45.7% | 32.6% | 21.7% |

References

- Van Der Linde, D.; Konings, E.E.; Slager, M.A.; Witsenburg, M.; Helbing, W.A.; Takkenberg, J.J.; Roos-Hesselink, J.W. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 2241–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bonnet, D.; Coltri, A.; Butera, G.; Fermont, L.; Le Bidois, J.; Kachaner, J.; Sidi, D. Detection of Transposition of the Great Arteries in Fetuses Reduces Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality. Circulation 1999, 99, 916–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tworetzky, W.; McElhinney, D.B.; Reddy, V.M.; Brook, M.M.; Hanley, F.L.; Silverman, N.H. Improved Surgical Outcome After Fetal Diagnosis of Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. Circulation 2001, 103, 1269–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Franklin, O.; Burch, M.; Manning, N.; Sleeman, K.; Gould, S.; Archer, N. Prenatal diagnosis of coarctation of the aorta improves survival and reduces morbidity. Heart 2002, 87, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holland, B.J.; Myers, J.A.; Woods, C.R. Prenatal diagnosis of critical congenital heart disease reduces risk of death from cardiovascular compromise prior to planned neonatal cardiac surgery: A meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 45, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donofrio, M.T.; Moon-Grady, A.J.; Hornberger, L.K.; Copel, J.A.; Sklansky, M.S.; Abuhamad, A.; Cuneo, B.F.; Huhta, J.C.; Jonas, R.A.; Krishnan, A.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of fetal cardiac disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014, 129, 2183–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, L.D.; Huggon, I.C. Counselling following a diagnosis of congenital heart disease. Prenat. Diagn. 2004, 24, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, L.; Dangel, J.; Fesslova, V.; Marek, J.; Mellander, M.; Oberhänsli, I.; Oberhoffer, R.; Sharland, G.; Simpson, J.; Sonesson, S.E. Recommendations for the practice of fetal cardiology in Europe. Association for European Paediatric Cardiology. Cardiol. Young 2004, 14, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, B.; Glickstein, J.S.; Levasseur, S.M.; Williams, I.A. Parents of Children with Congenital Heart Disease Prefer More Information than Cardiologists Provide. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2013, 8, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bratt, E.L.; Järvholm, S.; Ekman-Joelsson, B.M.; Mattson, L.Å.; Mellander, M. Parent’s experiences of counselling and their need for support following a prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease—A qualitative study in a Swedish context. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carlsson, T.; Bergman, G.; Wadensten, B.; Mattsson, E. Experiences of informational needs and received information following a prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defect. Prenat. Diagn. 2016, 36, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychik, J.; Donaghue, D.D.; Levy, S.; Fajardo, C.; Combs, J.; Zhang, X.; Szwast, A.; Diamond, G.S. Maternal Psychological Stress after Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease. J. Pediatr. 2013, 162, 302–307.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklansky, M.; Tang, A.; Levy, D.; Grossfeld, P.; Kashani, I.; Shaughnessy, R.; Rothman, A. Maternal psychological impact of fetal echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2002, 15, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, K.B.; Monk, C.; Glickstein, J.S.; Levasseur, S.M.; Simpson, L.L.; Kleinman, C.S.; Williams, I.A.; Simpson, L.L. Referral for fetal echocardiography is associated with increased maternal anxiety. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 31, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T.; Diego, M.; Hernandez-Reif, M.; Schanberg, S.; Kuhn, C.; Yando, R.; Bendell, D. Pregnancy anxiety and comorbid depression and anger: Effects on the fetus and neonate. Depress. Anxiety 2003, 17, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T. Prenatal depression effects on early development: A review. Infant Behav. Dev. 2011, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, E.J.H.; de Medina, P.G.R.; Huizink, A.C.; Bergh, B.R.H.V.D.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Visser, G.H.A. Prenatal maternal stress: Effects on pregnancy and the (unborn) child. Early Hum. Dev. 2002, 70, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, M. The potential influence of maternal stress hormones on development and mental health of the offspring. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2005, 19, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talge, N.M.; Neal, C.; Glover, V. Early Stress, Translational Research and Prevention Science Network: Fetal and neonatal experience on child and adolescent mental health. Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: How and why? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2007, 48, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizink, A.C.; De Medina, P.G.R.; Mulder, E.; Visser, G.H.; Buitelaar, J.K. Stress during pregnancy is associated with developmental outcome in infancy. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2003, 44, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacevic, A.; Bär, S.; Starystach, S.; Simmelbauer, A.; Elsässer, M.; Müller, A.; Mohammadi Motlagh, A.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Ostermayer, E.; Ewert, P.; et al. Objective Assessment of Counselling for Fetal Heart Defects: An Interdisciplinary Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kovacevic, A.; Simmelbauer, A.; Starystach, S.; Elsässer, M.; Müller, A.; Bär, S.; Gorenflo, M. Counseling for Prenatal Congenital Heart Disease—Recommendations Based on Empirical Assessment of Counseling Success. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (WHO Europe). Health Literacy. The Solid Facts. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/128703/e96854.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H.; (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kovacevic, A.; Simmelbauer, A.; Starystach, S.; Elsässer, M.; Sohn, C.; Müller, A.; Bär, S.; Gorenflo, M. Assessment of Needs for Counseling After Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease—A Multidisciplinary Approach. Klinische Pädiatrie 2018, 230, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, C.; Best, H. (Eds.) Handbuch der Sozialwissenschaftlichen Datenanalyse; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; 249p. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Classifying Educational Programmes. Manual for ISCED-97 Implementation in OECD Countries. 1999. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/41/42/1841854.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Kovacevic, A.; Bär, S.; Starystach, S.; Elsässer, M.; van der Locht, T.; Mohammadi Motlagh, A.; Ostermayer, E.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Ewert, P.; Gorenflo, M.; et al. Fetal Cardiac Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: How Does It Affect Parental Counseling? J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacevic, A.; Elsässer, M.; Fluhr, H.; Müller, A.; Starystach, S.; Bär, S.; Gorenflo, M. Counseling for fetal heart disease—current standards and best practice. Transl. Pediatr. 2021, 10, 2225–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousquet, G.; Orri, M.; Winterman, S.; Brugière, C.; Verneuil, L.; Revah-Levy, A. Breaking Bad News in Oncology: A Metasynthesis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2437–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storstein, A. Communication and neurology—bad news and how to break them. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2011, 124, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1. Transfer of Medical Knowledge (sum-score range = 5 to 25; α = 0.798, good) |

|

| 2. Transparency regarding the Treatment Process (sum-score range = 4 to 20; α = 0.808, very good) |

|

| 3. Trust in Medical Staff (sum-score range = 3 to 15; α = 0.811, very good) |

|

| 4. Perceived Situational Control (sum-score range = 1 to 5, α not applicable as only one item) |

|

| 5. Coping Resources (sum-score range = 3 to 15, α = 0.743, good) |

|

| Overall Counseling Success | Trust in Medical Staff | Transfer of Medical Knowledge | Coping Resources | Transparency Regarding the Treatment Process | Perceived Situational Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Factors | ||||||

| Interpersonal support by the physician during counseling | 0.616 *** | 0.670 *** | 0.288 *** | 0.567 *** | 0.462 *** | 0.317 *** |

| Frequent interruptions of the counseling by the physician | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | −0.223 *** | n.s. |

| Counseling in easy-to-understand terms | 0.249 *** | n.s. | 0.374 *** | 0.160 ** | 0.129 * | n.s. |

| Spatiotemporal Factors | ||||||

| Short period of time between suspected diagnosis and counseling | 0.135 ** | n.s. | n.s. | 0.149 ** | 0.150 ** | n.s. |

| No appropriate room during the consultation | n.s. | −0.119 * | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Informational Factors | ||||||

| Information materials received | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Unfulfilled need to receive information material | n.s. | n.s. | −0.253 *** | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Information materials helped to answer upcoming questions independently | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.157 ** | n.s. |

| Information how to obtain psychological support received | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Age | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.166 * |

| First language German | n.s. | 0.131 * | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Gender | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Sorrows | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Permanent relationship | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Social status | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| ISCED + | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Pre-existing medical knowledge | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Severity of fetal CHD ++ | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.132 * | n.s. | n.s. |

| Location | 0.102 * | 0.112 * | n.s. | n.s. | 0.103 * | n.s. |

| Counseling during COVID-19 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Corrected R2 | 0.557 | 0.478 | 0.410 | 0.462 | 0.384 | 0.141 |

| n +++ | 191 | 208 | 213 | 206 | 187 | 218 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kovacevic, A.; Wacker-Gussmann, A.; Bär, S.; Elsässer, M.; Mohammadi Motlagh, A.; Ostermayer, E.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Ewert, P.; Gorenflo, M.; Starystach, S. Parents’ Perspectives on Counseling for Fetal Heart Disease: What Matters Most? J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11010278

Kovacevic A, Wacker-Gussmann A, Bär S, Elsässer M, Mohammadi Motlagh A, Ostermayer E, Oberhoffer-Fritz R, Ewert P, Gorenflo M, Starystach S. Parents’ Perspectives on Counseling for Fetal Heart Disease: What Matters Most? Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(1):278. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11010278

Chicago/Turabian StyleKovacevic, Alexander, Annette Wacker-Gussmann, Stefan Bär, Michael Elsässer, Aida Mohammadi Motlagh, Eva Ostermayer, Renate Oberhoffer-Fritz, Peter Ewert, Matthias Gorenflo, and Sebastian Starystach. 2022. "Parents’ Perspectives on Counseling for Fetal Heart Disease: What Matters Most?" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 1: 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11010278

APA StyleKovacevic, A., Wacker-Gussmann, A., Bär, S., Elsässer, M., Mohammadi Motlagh, A., Ostermayer, E., Oberhoffer-Fritz, R., Ewert, P., Gorenflo, M., & Starystach, S. (2022). Parents’ Perspectives on Counseling for Fetal Heart Disease: What Matters Most? Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(1), 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11010278