Experimental Performances of Titanium Redox Electrodes as the Substitutes for the Ruthenium–Iridium Coated Electrodes Used in the Reverse Electrodialysis Cells for Hydrogen Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Chemicals and Equipment

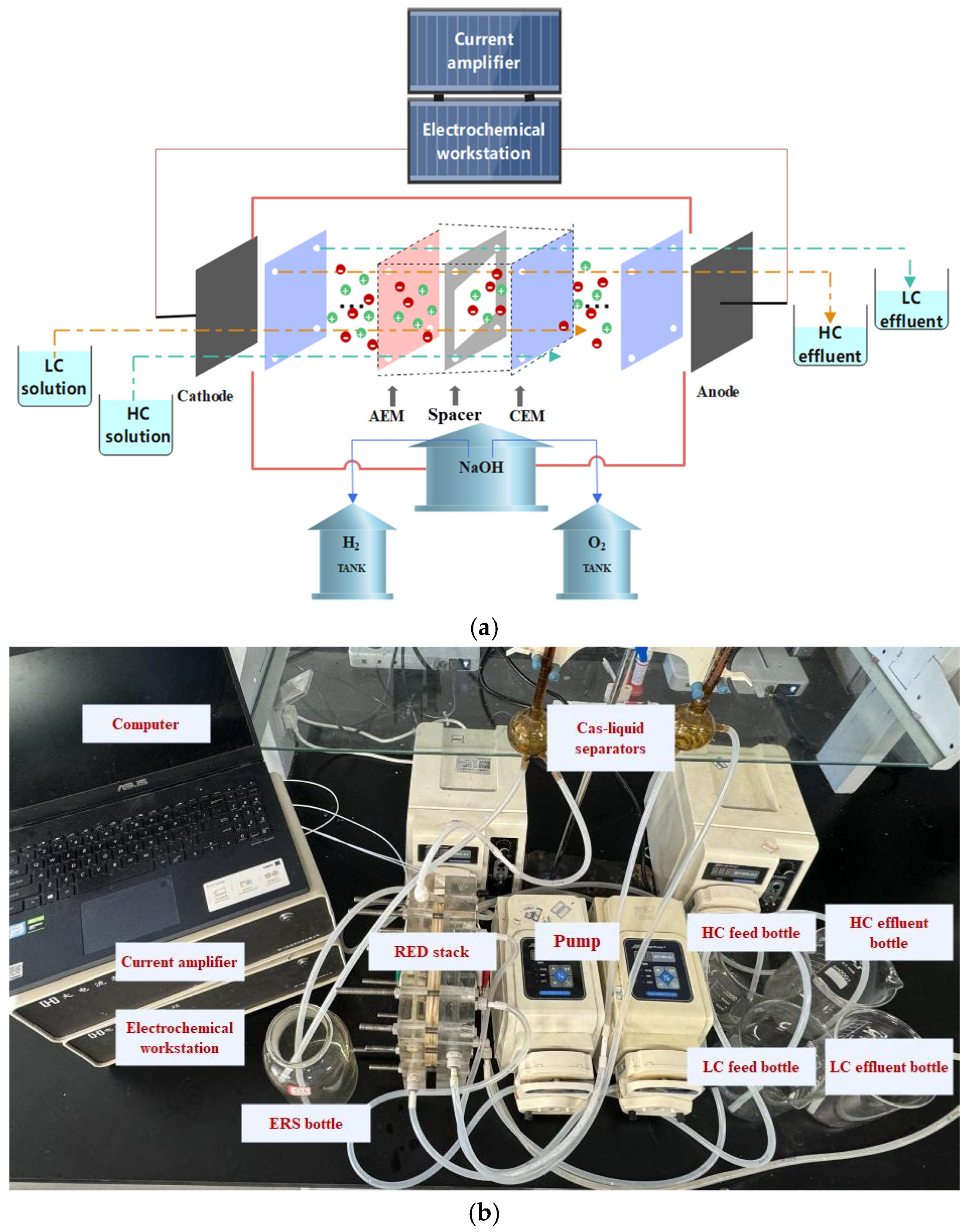

2.2. Design of Experimental System

2.3. RED Evaluation Methods

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Performance of the Mesh Titanium Plate Coated Oxide Iridium and Oxide Ruthenium as Electrodes

3.2. Performance of the Titanium Redox Electrodes with Specially Designed Structure

3.2.1. Under Varying HER Temperature Conditions

3.2.2. Under Varying ERS Concentration Conditions

3.2.3. Under Varying ERS Flow Conditions

3.3. Performance of the RED System Under the Comprehensive Optimum Conditions

4. Conclusions

- -

- Based on the present study, the hydrogen evolution efficiency of conventional Ti mesh electrodes reaches only 78.56% of the Ru-Ir-coated Ti mesh electrode. The introduction of a spiked Ti mesh structure increases the efficiency by 5.46%.

- -

- Building on the spiked structure of electrodes, increasing the ERS temperature from 15 °C to 45 °C enhances hydrogen production by 14.1%; raising the ERS concentration from 0.1 M to 0.7 M slightly increases oxygen evolution but reduces hydrogen production; decreasing the ERS flow rate from 130 mL·min−1 to 50 mL·min−1 cuts down the power generation performance but decreases the hydrogen evolution efficiency.

- -

- Considering all operating parameters, the optimal conditions were determined as an ERS temperature of 45 °C, a concentration of 0.1 M, and a flow rate of 50 mL·min−1, under which hydrogen production reaches 89.7% of that of Ti-coated Ru-Ir electrodes. Moreover, the redox electrodes’ cost decreases over 60%, confirming the feasibility of replacing noble-metal electrodes with low-cost electrodes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Logan, B.E.; Elimelech, M. Membrane-based processes for sustainable power generation using water. Nature 2012, 488, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, J.W.; Hamelers, H.V.M.; Buisman, C.J.N. Energy recovery from controlled mixing salt and fresh water with a reverse electrodialysis system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5785–5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrino, A.; Campisi, G.; Proietto, F.; Tamburini, A.; Cipollina, A.; Galia, A.; Micale, O.; Scialdone, O. Green hydrogen production via reverse electrodialysis and assisted reverse electrodialysis electrolyser: Experimental analysis and preliminary economic assessment. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 76, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranade, A.; Singh, K.; Tamburini, A.; Micale, G.; Vermaas, D.A. Feasibility of producing electricity, hydrogen, and chlorine via reverse electrodialysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 16062–16072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerman, J.; Saakes, M.; Metz, S.J.; Harmsen, G.J. Reverse electrodialysis: A validated process model for design and optimization. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 166, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, T. Electrodialysis of concentrated brine from RO plant to produce coarse salt and freshwater. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 450, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guler, E.; van Baak, W.; Saakes, M.; Nijmeijer, K. Monovalent-ion-selective membranes for reverse electrodialysis. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 455, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattle, R.E. Production of electric power by mixing fresh and salt water in the hydroelectric pile. Nature 1954, 174, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufa, R.A.; Rugiero, E.; Chanda, D.; Hnát, J.; van Baak, W.; Veerman, J.; Fontananova, E.; Di Profio, G.; Drioli, E.; Bouzek, K.; et al. Salinity gradient power-reverse electrodialysis and alkaline polymer electrolyte water electrolysis for hydrogen production. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 514, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, T. Storable hydrogen production by reverse electro-electrodialysis. Membranes 2017, 544, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiang, C.; Shehzad, M.A.; Wang, Y.; Feng, H.; Yang, Z.; Xu, T. Water-dissociation-assisted electrolysis for hydrogen production in a salinity power cell. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 13023–13030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, A.A. Uphill transport in improved reverse electrodialysis by removal of divalent cations in the dilute solution: A Nernst-Planck based study. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 598, 117784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, S.B.; Zimmermann, P.; Wilhelmsen, Ø.; Lamb, J.J.; Bock, R.; Burheim, O.S. Heat to hydrogen by reverse electrodialysis—Using a non-equilibrium thermodynamics model to evaluate hydrogen production concepts utilising waste heat. Energies 2022, 15, 6011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Solberg, S.B.B.; Tekinalp, Ö.; Lamb, J.J.; Wilhelmsen, Ø.; Deng, L.; Burheim, O.S. Heat to hydrogen by RED—Reviewing membranes and thermolytic solutions for the RED heat engine concept. Energies 2021, 14, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzell, M.C.; Ivanov, I.; Cusick, R.D.; Zhu, X.; Logan, B.E. Comparison of hydrogen production and electrical power generation for energy capture in closed-loop ammonium bicarbonate reverse electrodialysis systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 1632–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, C.; Pintossi, D.; Saakes, M.; Borneman, Z.; Brilman, W.; Nijmeijer, K. Electrode segmentation in reverse electrodialysis: Improved power and energy efficiency. Desalination 2020, 492, 114604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.A.; Hubert, M.A.; Capuano, C.; Manco, J.; Danilovic, N.; Valle, E.; Hellstern, T.R.; Ayers, K.; Jaramillo, T.F. A non-precious metal hydrogen catalyst in a commercial polymer electrolyte membrane electrolyser. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2022, 17, 1071–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wu, X.; Xu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Leng, Q. Methyl orange degradation and hydrogen production simultaneously by a reverse electrodialysis–electrocoagulation coupling system powered by salinity gradient energy. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 318, 116550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Zhu, X.; Wu, X.; Guan, H. Ion-Exchange Membrane Permselectivity: Experimental Evaluation of Concentration Dependence, Ionic Species Selectivity, and Temperature Response. Separations 2025, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Jeong, N.; Kim, C.S.; Hwang, K.S.; Kim, H.; Nam, J.Y.; Jwa, E.; Yang, S.; Choi, J. Reverse electrodialysis (RED) using a bipolar membrane to suppress inorganic fouling around the cathode. Water Res. 2019, 166, 115078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Huang, Y.; Yip, N.Y. Advancing the conductivity–permselectivity trade-off of electrodialysis ion-exchange membranes with sulfonated CNT nanocomposites. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 610, 118259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufa, R.A.; Pawlowski, S.; Veerman, J.; Bouzek, K.; Fontananova, E.; Di Profio, G.; Velizarov, S.; Crespo, J.G.; Nijmeijer, K.; Curcio, E. Progress and prospects in reverse electrodialysis for salinity gradient energy conversion and storage. Appl. Energy 2018, 225, 290–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Xu, S.; Leng, Q.; Wang, S. A serial system of multi-stage reverse electrodialysis stacks for hydrogen production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 251, 114932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Liang, Y.; Gao, P.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B. Titanium substitution effects on the structure, activity, and stability of nanoscale ruthenium oxide oxygen evolution electrocatalysts: Experimental and computational study. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 11752–11775. [Google Scholar]

- Thangamuthu, M.; Kohlrausch, E.C.; Li, M.; Speidel, A.; Clare, A.T.; Plummer, R.; Geary, P.; Murray, J.W.; Khlobystov, A.N.; Fernandes, J.A. From scrap metal to highly efficient electrodes: Harnessing the nanotextured surface of swarf for effective utilisation of Pt and Co for hydrogen production. J. Mater. Chem. 2024, 12, 15137–15144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakhella, K.W.; Bock, R.; Burheim, O.S.; Seland, F.; Einarsrud, K.E. Heat to H2: Using waste heat for hydrogen production through reverse electrodialysis. Energies 2019, 12, 3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gao, H.; Chen, Y. Enhanced ionic conductivity and power generation using ion-exchange resin beads in a reverse-electrodialysis stack. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 14717–14724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, S.; Hamann, C.H. The pH-dependence of the hydrogen exchange current density at smooth platinum in alkaline solution. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 1975, 60, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A.; Koper, M.T.M. The interrelated effect of cations and electrolyte pH on the hydrogen evolution reaction on gold electrodes in alkaline media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 13452–13462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, J.; Li, M.; Wang, H. A novel hydrogen production system based on multistage reverse electrodialysis heat engine. Sci. Technol. Energy Transit. 2025, 80, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo-Castaño, S.; Sánchez-Sáenz, C.I. Design and optimization of a reverse electrodialysis stack for energy generation through salinity gradients. Dyna 2017, 84, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lv, Y.; Sun, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, S. Effects of electrode rinse solution on performance of hydrogen and electricity cogeneration system by reverse electrodialysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 287, 117122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, X.; Li, B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H. Toward redox-free reverse electrodialysis with carbon-based flow electrodes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 12845–12855. [Google Scholar]

| Equipment | Model | Precision | Range | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peristaltic pump for working solution | KCP | ±5% | 50~260 mL | Kamoer, Shanghai, China |

| Electrode liquid peristaltic pump | BT300-2J | 0.1 rpm | 0~300 rpm | Longer, London, UK |

| Conductivity meter | FiveEasy Plus | ±0.5% | 0~500 ms·cm−1 | Mettler Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland |

| Electrochemical workstation | CHI660E | 0.2% | 0~0.25 A | CH Instruments, Bee Cave, TX, USA |

| Current amplifier | CHI660C | ±2 A | CH Instruments, USA | |

| Electronic balance | AR124N | 0.0001 g | 0~120 g | Ohaus, Parsippany, NJ, USA |

| Constant temperature water tank | F34-ME | ±0.05 °C | −30–150 °C | JULABO, Seelbach, Germany |

| Magnetic stirrer | RS-6DN | N/A | 100~1500 rpm | ASONE, Osaka, Japan |

| Spacer Material | Thick Spacer δ | Porosity ε (%) | Shielding Coefficient | Resistance Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET | 220 μm | 67 | 1.73 | 2.02 |

| Membrane Type | δm (μm) | α * (%) | Ion-Exchange Capacity (meq·g−1) | AR ** (Ω·cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEM-Type 10 | 135 | 99 | 1.5 | 2 |

| AEM-Type 10 | 125 | 95 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Han, Z.; Wu, X.; Xu, L.; He, P. Experimental Performances of Titanium Redox Electrodes as the Substitutes for the Ruthenium–Iridium Coated Electrodes Used in the Reverse Electrodialysis Cells for Hydrogen Production. Membranes 2026, 16, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010026

Han Z, Wu X, Xu L, He P. Experimental Performances of Titanium Redox Electrodes as the Substitutes for the Ruthenium–Iridium Coated Electrodes Used in the Reverse Electrodialysis Cells for Hydrogen Production. Membranes. 2026; 16(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Zhaozhe, Xi Wu, Lin Xu, and Ping He. 2026. "Experimental Performances of Titanium Redox Electrodes as the Substitutes for the Ruthenium–Iridium Coated Electrodes Used in the Reverse Electrodialysis Cells for Hydrogen Production" Membranes 16, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010026

APA StyleHan, Z., Wu, X., Xu, L., & He, P. (2026). Experimental Performances of Titanium Redox Electrodes as the Substitutes for the Ruthenium–Iridium Coated Electrodes Used in the Reverse Electrodialysis Cells for Hydrogen Production. Membranes, 16(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010026