Towards a Circular Economy in Electroless Pore-Plated Pd/PSS Composite Membranes: Pd Recovery and Porous Support Reuse

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fabrication of the Original Pd/CeO2/PSS Composite Membranes

2.2. Pd Layer Removal via Nitric Acid Leaching and Preparation of a New Membrane from the Recovered Support

2.3. Permeation Tests

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Original Pd/CeO2/PSS Membranes

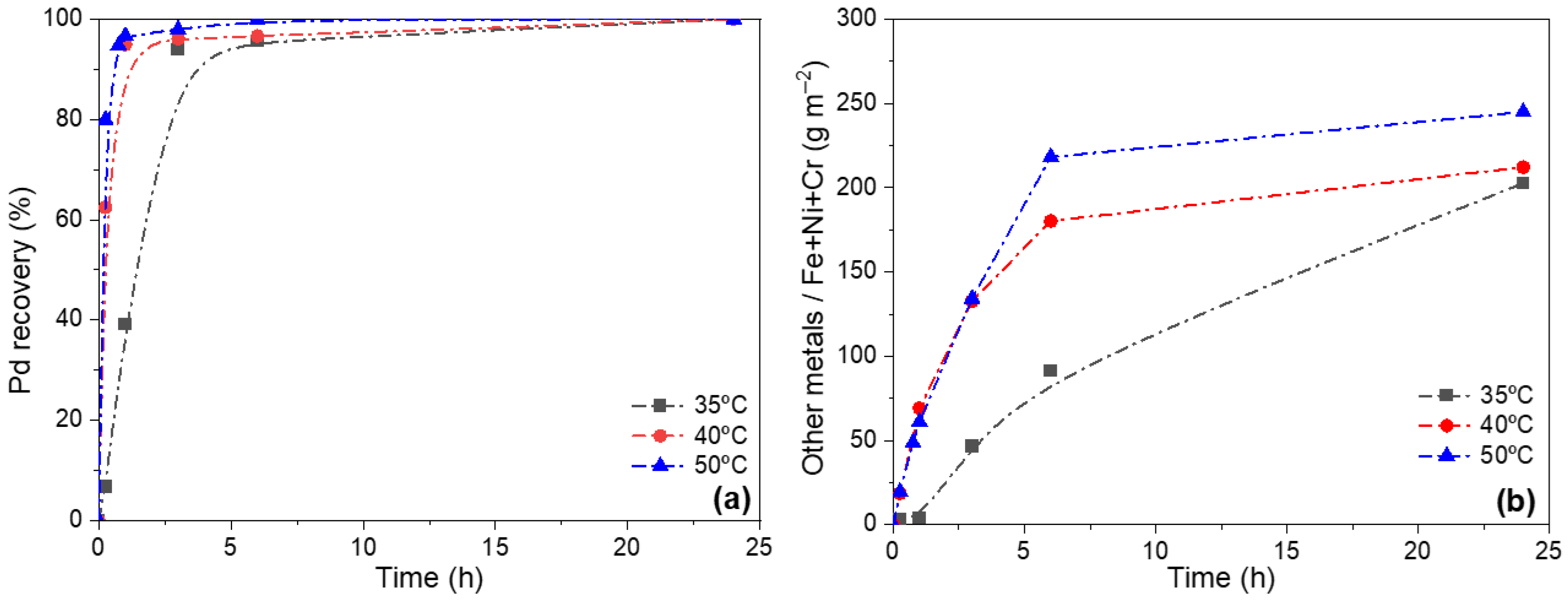

3.2. Effect of Temperature in Leaching Treatment for Pd Release from Pd/CeO2/PSS Membranes

3.3. Effect of HNO3 Concentration in Leaching Treatment for Pd Release from Pd/CeO2/PSS Membranes

3.4. Process for the Manufacture of a New Membrane with a Recycled Support

3.4.1. Characterization of the Recovered Membrane Support

3.4.2. Characterization and Performance of the Recycled Membrane

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olkuski, T.; Suwała, W.; Wyrwa, A.; Zyśk, J.; Tora, B. Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends. Open Chem. 2021, 19, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumar, P.; Kumar, A.; Afzal, M.; Bhogilla, S.; Sharma, P.; Parida, A.; Jana, S.; Kumar, E.A.; Pai, R.K.; Jain, I.P. Review on large-scale hydrogen storage systems for better sustainability. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 33223–33259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groll, M. Can climate change be avoided? Vision of a hydrogen-electricity energy economy. Energy 2023, 264, 126029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodkhe, R.G.; Shrivastava, R.L.; Soni, V.K.; Chadge, R.B. A review of renewable hydrogen generation and proton exchange membrane fuel cell technology for sustainable energy development. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2023, 18, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeje, S.O.; Marazani, T.; Obiko, J.O.; Shongwe, M.B. Advancing the hydrogen production economy: A comprehensive review of technologies, sustainability, and future prospects. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 78, 642–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, D.; Capocelli, M.; De Falco, M.; Franchi, G.; Piemonte, V. Mass transfer coefficient in multi-stage reformer/membrane modules for hydrogen production. Membranes 2018, 8, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, F.; Fernandez, E.; Corengia, P.; van Sint Annaland, M. Recent advances on membranes and membrane reactors for hydrogen production. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 92, 40–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hönig, F.; Rupakula, G.D.; Duque-Gonzalez, D.; Ebert, M.; Blum, U. Enhancing the Levelized Cost of Hydrogen with the Usage of the Byproduct Oxygen in a Wastewater Treatment Plant. Energies 2023, 16, 4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabuddin, M.; Rhamdhani, M.A.; Brooks, G.A. Technoeconomic Analysis for Green Hydrogen in Terms of Production, Compression, Transportation and Storage Considering the Australian Perspective. Processes 2023, 11, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetinović, D.; Erić, A.; Anđelković, J.; Ćetenović, N.; Jovanović, M.; Bakić, V. Economic Viability of Hydrogen Production via Plasma Thermal Degradation of Natural Gas. Processes 2025, 13, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, A.; Gajec, M.; Holewa-Rataj, J.; Kukulska-Zając, E.; Rataj, M. Hydrogen Purification Technologies in the Context of Its Utilization. Energies 2024, 17, 3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zou, D.; Pan, Q.; Jiang, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, C. Effect of single atomic layer graphene film on the thermal stability and hydrogen permeation of Pd-coated Nb composite membrane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 8359–8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, B.; Goswami, N.; Parida, S.C.; Singha, A.K.; Rath, B.N.; Sodaye, H.S.; Bindal, R.C.; Kar, S. Tantalum membrane reactor for enhanced HI decomposition in Iodine-Sulphur (IS) thermochemical process of hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 5719–5732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryi, S.K.; Park, J.S.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, S.H. Methane steam reforming with a novel catalytic nickel membrane for effective hydrogen production. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 339, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimov, V.N.; Bobylev, I.V.; Busnyuk, A.O.; Kolgatin, S.N.; Kuzenov, S.R.; Peredistov, E.U.; Livshits, A.I. Extraction of ultrapure hydrogen with V-alloy membranes: From laboratory studies to practical applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 13318–13327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzenov, S.R.; Alimov, V.N.; Busnyuk, A.O.; Peredistov, E.U.; Livshits, A.I. Hydrogen transport through V-Fe alloy membranes: Permeation, diffusion, effects of deviation from Sieverts’ law. J. Membr. Sci. 2023, 674, 121504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, G.; Araújo, T.; da Silva Lopes, T.; Sousa, J.; Mendes, A. Recent advances in membrane technologies for hydrogen purification. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 7313–7338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Diaz, D.; Alique, D.; Calles, J.A.; Sanz, R. Pd-thickness reduction in electroless pore-plated membranes by using doped-ceria as interlayer. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 7278–7289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Feng, Z.; Wang, X. Palladium-related metallic membranes for hydrogen separation and purification: A review. Fuel 2025, 386, 134192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alique, D.; Leo, P.; Martinez-Diaz, D.; Calles, J.A.; Sanz, R. Environmental and cost assessments criteria for selection of promising palladium membranes fabrication strategies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marcoberardino, G.; Knijff, J.; Binotti, M.; Gallucci, F.; Manzolini, G. Techno-economic assessment in a fluidized bed membrane reactor for small-scale H2 production: Effect of membrane support thickness. Membranes 2019, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinzadeh, M.; Petersen, J. Recovery of Pt, Pd, and Rh from spent automotive catalysts through combined chloride leaching and ion exchange: A review. Hydrometallurgy 2024, 228, 106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ding, W.; Jin, X.; Yu, J.; Hu, X.; Huang, Y. Toward extensive application of Pd/ceramic membranes for hydrogen separation: A case study on membrane recycling and reuse in the fabrication of new membranes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 3528–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, L.; Moscardini, E.; Baldassari, L.M.; Forte, F.; Coletta, J.; Palo, E.; Cosentino, V.; Angelini, F.; Arratibel, A. Regeneration of Exhausted Palladium-Based Membranes: Recycling Process and Economics. Membranes 2022, 12, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Y.; Yang, F.; Pan, J.; Wang, S. Study on the Corrosion Resistance Mechanism of Nitric Acid Passivation on 316L and SUS329J3L Duplex Stainless Steels in a Denitrification Agent. Langmuir 2025, 41, 7669–7683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Carballes, A.J.; Vizcaíno, A.J.; Sanz, R.; Calles, J.A.; Alique, A. Continuous flowing electroless pore-plating to fabricate H2-selective Pd-membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 377, 134508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furones, L.; Alique, D. Interlayer Properties of In-Situ Oxidized Porous Stainless Steel for Preparation of Composite Pd Membranes. ChemEngineering 2017, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, B.; Cook, P.; Hobbs, J.; Engelberg, D.L. Corrosion Behavior of Cold Rolled Type 316L Stainless Steel in HCl-Containing Environments. Corrosion 2017, 73, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, J.; Ikeda, T.; Tanaka, D.A.P.; Sato, K.; Suzuki, T.M.; Mizukami, F. An investigation of thermal stability of thin palladium-silver alloy membranes for high temperature hydrogen separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 366, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnolin, S.; Melendez, J.; Di Felice, L.; Gallucci, F. Surface roughness improvement of Hastelloy X tubular filters for H2 selective supported Pd-Ag alloy membranes preparation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 28505–28517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, M.; Afra, B.; Dehghani-Mobarake, M.; Bahmani, M. Preparation of a Pd membrane on a WO3 modified Porous Stainless Steel for hydrogen separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 333, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidifar, M.; Babaluo, A.A. Hydrogen flux improvement through palladium and its alloy membranes: Investigating influential parameters—A review. Fuel 2025, 379, 133038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Villanueva, D.; Alique, D.; Vizcaíno, A.J.; Calles, J.A.; Sanz, R. On the long-term stability of Pd-membranes with TiO2 intermediate layers for H2 purification. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 11402–11416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M1 | M2 | [26] | RSD (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-Cr oxides layer (g·m−2) | 96.9 | 86.5 | 89.1 | 6.0 |

| Pd-CeO2 (g·m−2) | 9.2 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 8.3 |

| Pd (g·m−2) | 95.2 | 102.2 | 110.6 | 7.5 |

| Pd gravimetric thickness (µm) | 7.9 | 8.5 | 9.2 | 7.6 |

| Element | Leaching Temperature | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 35 °C | 40 °C | 50 °C | |

| O | 17.3 ± 1.2 | 16.9 ± 0.5 | 15.3 ± 1.3 |

| Cr | 13.9 ± 1.7 | 17.5 ± 0.4 | 17.3 ± 2.4 |

| Fe | 37.6 ± 5.6 | 50.5 ± 0.8 | 50.2 ± 3.5 |

| Ni | 5.0 ± 0.6 | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 6.8 ± 0.5 |

| Pd | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Ce | 25.8 ± 6.7 | 8.7 ± 1.6 | 10.2 ± 5.9 |

| Element | HNO3 Concentration (vol.%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15% | 30% | 45% | 65% | |

| O | 13.4 ± 1.3 | 17.3 ± 1.2 | 21.7 ± 2.2 | 17.0 ± 0.5 |

| Cr | 18.8 ± 1.5 | 13.9 ± 1.7 | 21.0 ± 3.1 | 17.5 ± 0.4 |

| Fe | 49.4 ± 0.4 | 37.6 ± 5.6 | 50.2 ± 1.6 | 50.6 ± 0.9 |

| Ni | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.6 | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 6.3 ± 0.2 |

| Pd | 0.8 ± 0.2 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Ce | 10.0 ± 3.0 | 25.8 ± 6.7 | 15.5 ± 15.0 | 8.5 ± 1.8 |

| Geometry | Support | Interlayer | Selective Layer | Thickness (µm) | T (°C) | ∆P (kPa) | k (mol s−1 m−2 Pa−0.5) | Ea (kJ mol−1) | αH2/N2 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planar | Al2O3 | - | Pd-Ag | 3.7 | 550 | 101.3 | 3.53 × 10−6 | 8.6 | >1000 | [29] |

| Tubular | Hastelloy X | Bohemite | Pd-Ag | 6.8 | 500 | 100 | 4.47 × 10−4 a | 6.53 | 512 | [30] |

| Planar | PSS | WO3 | Pd-Ag | 12 | 500 | 900 | 2.06 × 10−8 a | 14.7 | >1000 | [31] |

| Tubular | PSS | SAPO-34 | Pd | 9 | 450 | 100 | 0.71 × 10−6 a | 17.1 | 866 | [32] |

| Tubular | PSS | Pd-TiO2 | Pd | 9.7 | 400 | 200 | 2.97 × 10−4 | 14.9 | >10,000 | [33] |

| Tubular | PSS | Pd-CeO2 | Pd | 9.1 | 400 | 100 | 6.26 × 10−4 | 13.1 | >10,000 | [18] |

| Planar | PSS | Pd-CeO2 | Pd | 9.2 | 400 | 150 | 3.88 × 10−4 4.28 × 10−4 | 8.2–9.8 | >10,000 | [26] |

| Planar | PSS | Pd-CeO2 | Pd | 8.5 | 400 | 150 | 3.57 × 10−4 3.83 × 10−4 | 14.1–15 | >10,000 | This work |

| Planar | Recycled PSS | Pd-CeO2 | Pd | 9.9 | 400 | 150 | 3.77 × 10−4 4.01 × 10−4 | 9.5–12.4 | >10,000 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Santos-Carballes, A.J.; Alique, D.; Sanz, R.; Vizcaíno, A.J.; Calles, J.A. Towards a Circular Economy in Electroless Pore-Plated Pd/PSS Composite Membranes: Pd Recovery and Porous Support Reuse. Membranes 2026, 16, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010028

Santos-Carballes AJ, Alique D, Sanz R, Vizcaíno AJ, Calles JA. Towards a Circular Economy in Electroless Pore-Plated Pd/PSS Composite Membranes: Pd Recovery and Porous Support Reuse. Membranes. 2026; 16(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos-Carballes, Alejandro J., David Alique, Raúl Sanz, Arturo J. Vizcaíno, and José A. Calles. 2026. "Towards a Circular Economy in Electroless Pore-Plated Pd/PSS Composite Membranes: Pd Recovery and Porous Support Reuse" Membranes 16, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010028

APA StyleSantos-Carballes, A. J., Alique, D., Sanz, R., Vizcaíno, A. J., & Calles, J. A. (2026). Towards a Circular Economy in Electroless Pore-Plated Pd/PSS Composite Membranes: Pd Recovery and Porous Support Reuse. Membranes, 16(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010028