Experimental and Modeling Study of a Semi-Continuous Slurry Reactor–Pervaporator System for Isoamyl Acetate Production Using a Commercial Pervaporation Membrane

Abstract

1. Introduction

Historical Background and Evolution of Reactive Pervaporation

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Catalyst

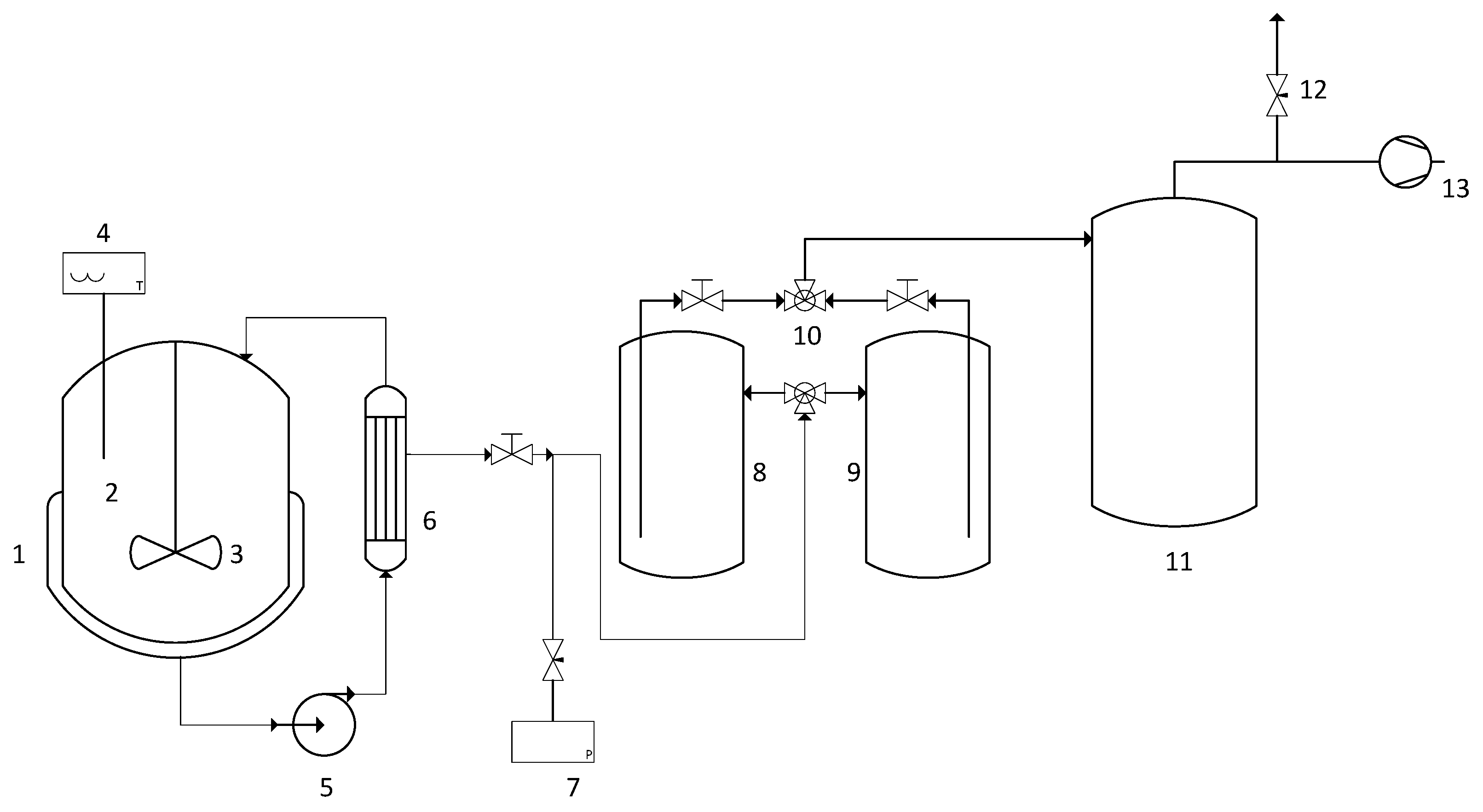

2.2. Experimental Setup

2.3. Hydrodynamic Analysis

2.4. Experimental Procedure

2.5. Analytical Methods

2.6. Membrane Characterization

3. Modeling Approach

3.1. Thermodynamic Model

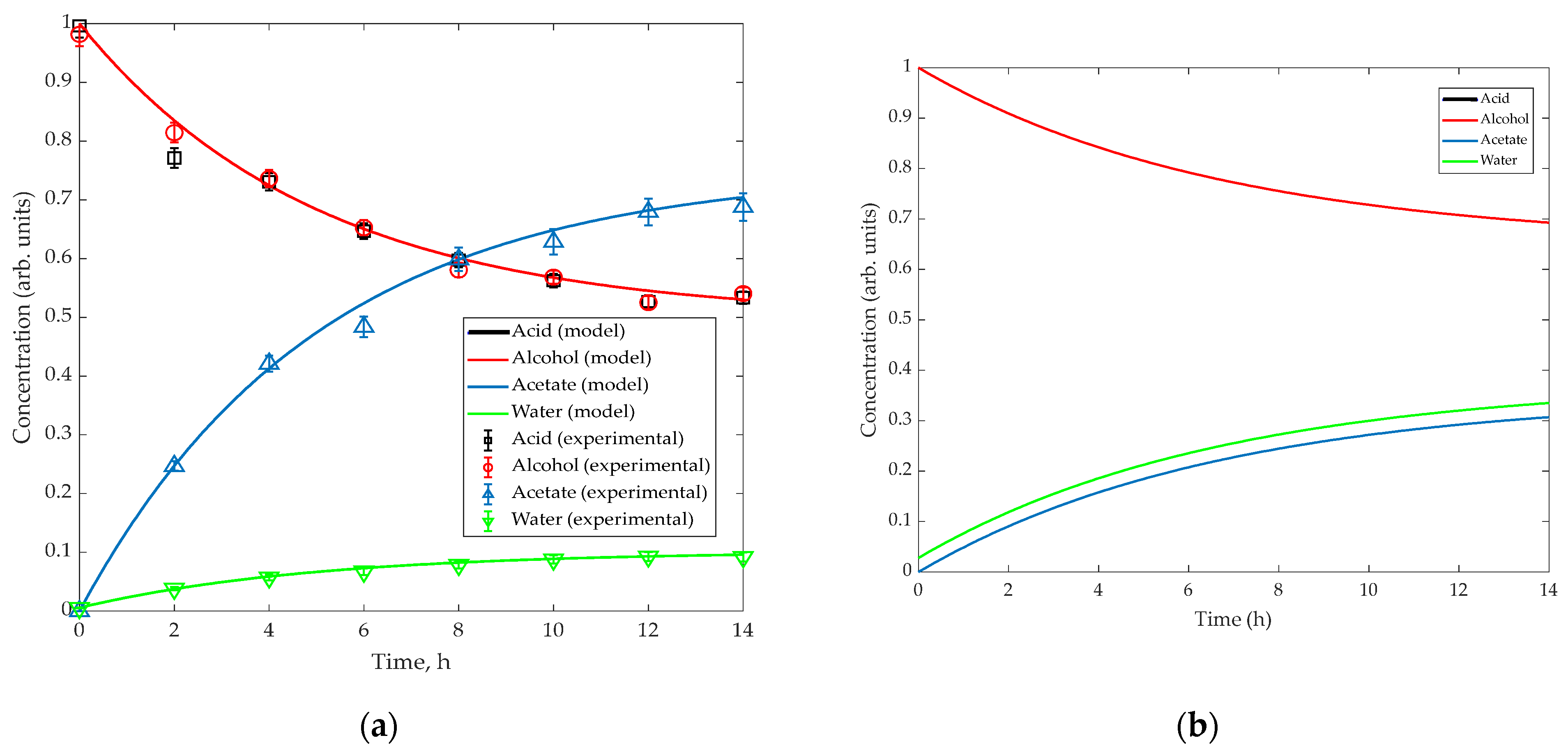

3.2. Kinetic Model

3.3. Membrane Transport Model

3.4. Reactor and System Mass Balances

3.5. Dimensionless Design Parameters

3.6. Numerical Solution

4. Prototype Design and Simulation

4.1. Dimensionless Analysis

4.2. Parameter Ranges and Simulation Matrix

4.3. Simulation Results

4.4. Design Guidance

- For membrane areas below 40 cm2 L−1 (low ), conversion becomes limited by dehydration capacity.

- For 50 cm2 L−1, the equilibrium shift becomes significant, and conversions above 70% can be theoretically achieved at moderate catalyst loadings (40–50 g L−1).

5. Experimental Results and Discussion

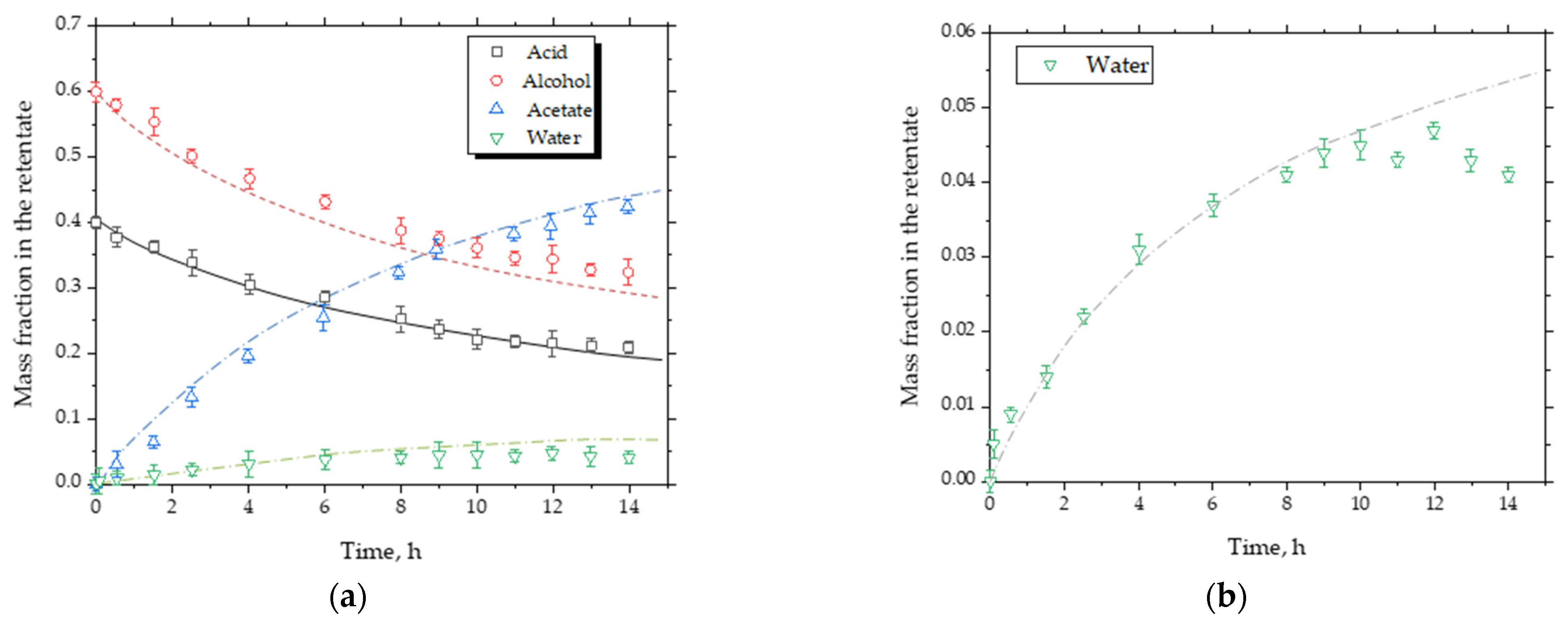

5.1. Validation of Model-Based Design

5.2. Conversion and Water Removal Behavior

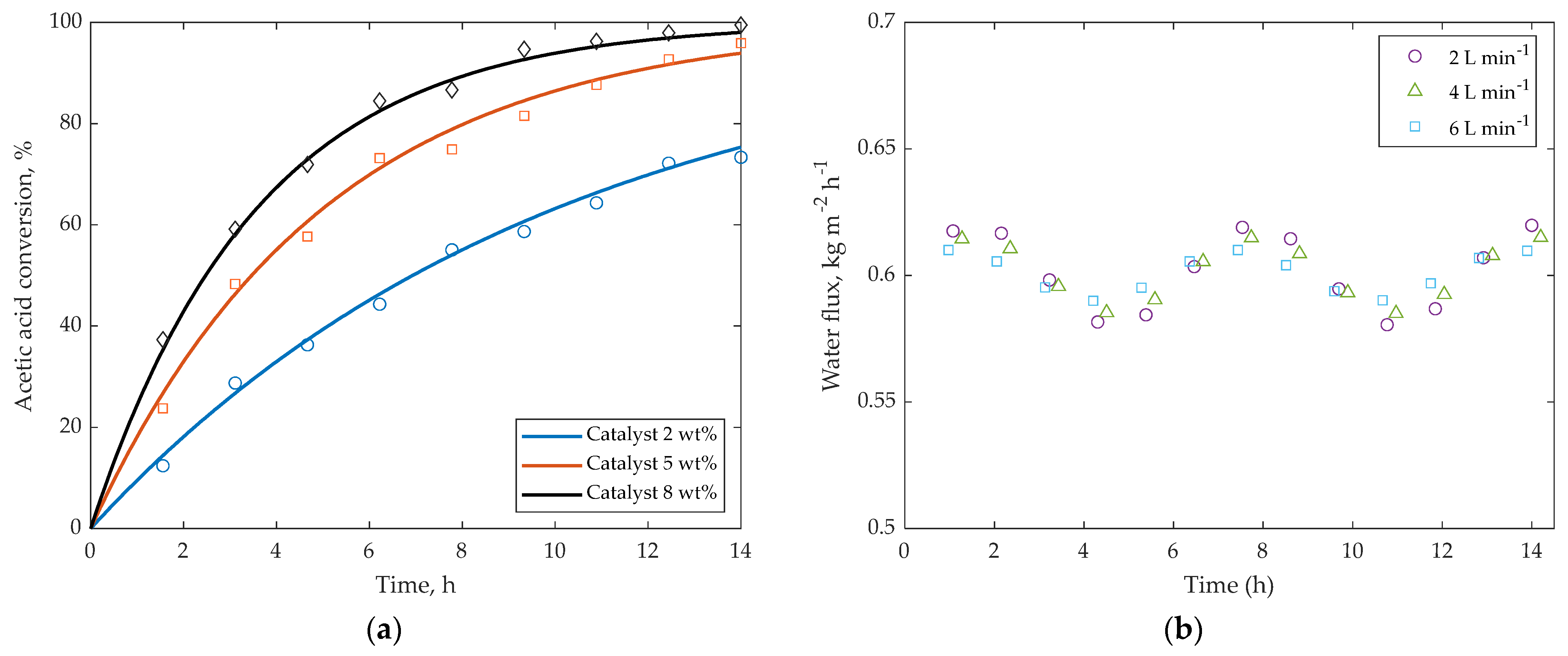

5.3. Membrane Performance

5.3.1. Flux and Selectivity

5.3.2. Membrane Stability Considerations

5.4. Effect of Catalyst Loading and Hydrodynamics

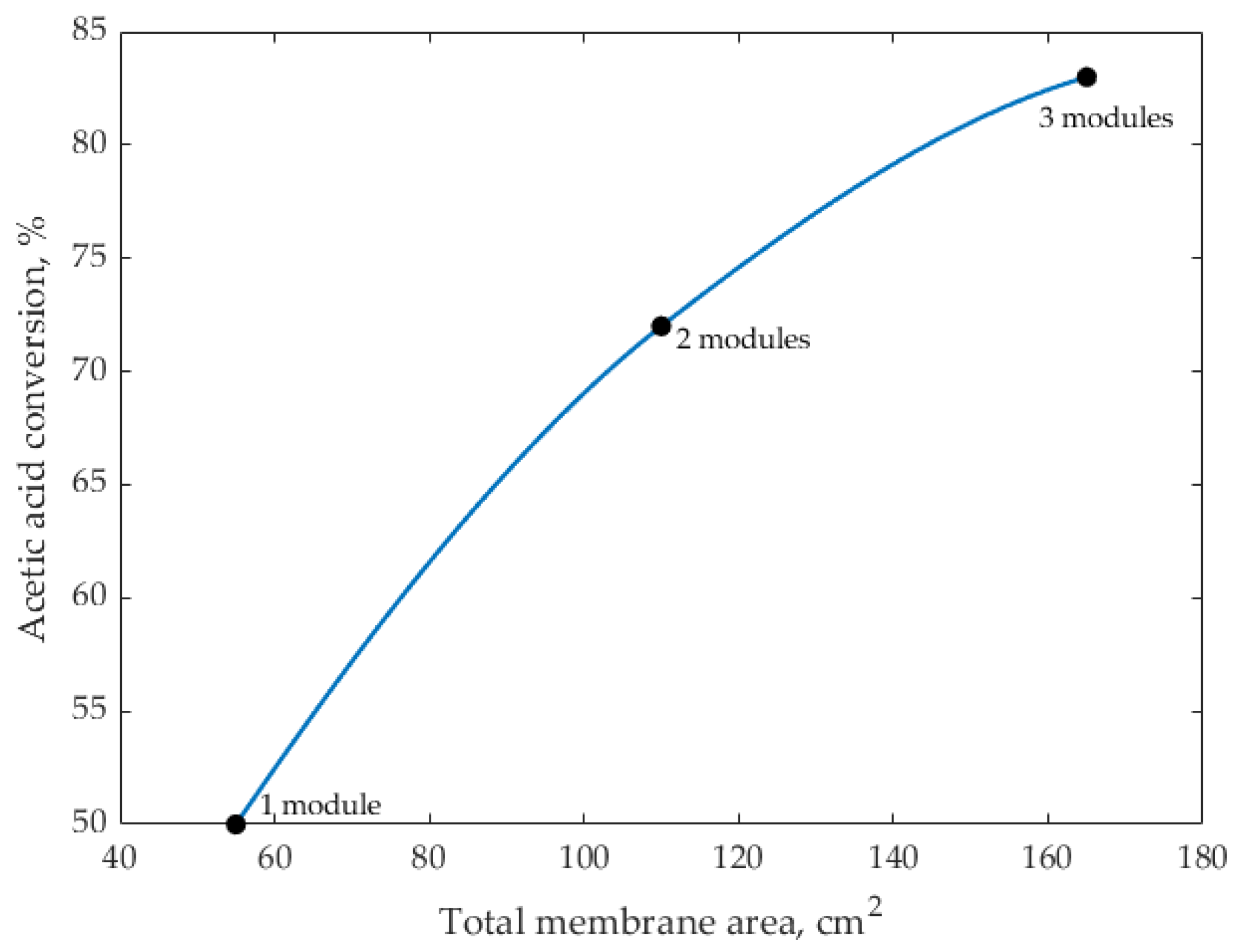

5.5. Scale-Up Analysis

5.6. Comparison with Literature and Process Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Symbols | |

| Surface area | |

| a | Liquid-phase activity |

| k | Rate constant |

| Keq | Chemical equilibrium constant |

| J | Membrane flux |

| Total reactive mass (initial) | |

| N | Number of mol |

| r | Reaction rate |

| t | Time |

| T | Temperature |

| Reactor volume | |

| w | Mass |

| x | Molar fraction |

| X | Fractional conversion |

| Z | Membrane thickness |

| Subscripts | |

| i | Component |

| j | Component |

| m | Membrane |

| Abbreviations | |

| HAc | Acetic acid |

| E | Isoamyl acetate |

| hom | Homogeneous |

| het | Heterogeneous |

| liq | Liquid |

| NRTL | Non-Random Two-Liquid |

| ROH | Isoamyl alcohol |

| W | Water |

References

- Tse, T.J.; Chen, C.; Huang, D. Value-Added Products from Ethanol Fermentation—A Review. Fermentation 2021, 7, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardebili, S.M.S.; Ardebili, Z.O.; Hesaraki, S.; Darvishnia, M. A Review on Higher Alcohols of Fusel Oil as a Renewable Fuel. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 128, 109914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel-Morgenstern, S. Membrane Reactors: Distributing Reactants to Improve Selectivity and Yield; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Diban, N.; Aguayo, A.T.; Bilbao, J.; Urtiaga, A.; Ortiz, I. Membrane Reactors for In Situ Water Removal: A Review of Applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 10342–10354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.A.; Gil, I.D.; Rodríguez, G. Fluid Phase Equilibria for the Isoamyl Acetate Production by Reactive Distillation. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2020, 518, 112647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremani, M.; Ghasemzadeh, K.; Jalilnejad, E.; Iulianelli, A. A Theoretical Analysis on a Multi-Bed Pervaporation Membrane Reactor during Levulinic Acid Esterification Using the Computational Fluid Dynamic Method. Membranes 2021, 11, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandane, V.S.; Rathod, A.P.; Sonawane, S.S.; Kodape, S.M. Esterification processes in membrane reactors. In Current Trends and Future Developments on (Bio-) Membranes. Recent Achievements in Chemical Processes in Membrane Reactor; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, C.; Liu, C.; Ying, Y.; Lu, L.; Zhang, C.; Baeyens, J.; Si, Z.; Zhang, X.; Qin, P. Recent progress in hydrophobic pervaporation membranes for phenol recovery. Green Energy Environ. 2025, 10, 1828–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, K.L.; Eisenacher, M. Process Intensification Strategies for Esterification: Kinetic Modeling, Reactor Design, and Sustainable Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, G.; Keshav, A.; Anandkumar, J. Review on Pervaporation: Theory, Membrane Performance, and Application to Intensification of Esterification Reaction. J. Eng. 2015, 2015, 927068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Javed, F.; Shamair, Z.; Hafeez, A.; Fazal, T.; Aslam, A.; Zimmerman, W.B.; Rehman, F. Current developments in esterification reaction: A review on process and parameters. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 103, 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, A.; Gallucci, F. Membranes for Membrane Reactors: Preparation, Optimization and Selection; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: West Sussex, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Penkova, A.; Polotskaya, G.; Toikka, A. Pervaporation Composite Membranes for Ethyl Acetate Production. Chem. Eng. Process. 2015, 87, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.T.; Gmehling, J. Esterification of Acetic Acid with Isopropanol Coupled with Pervaporation. Part I: Kinetics and Pervaporation Studies & Part II: Study of a Pervaporation Reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2006, 123, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Gan, L.; Liu, S.; Zhou, H.; Wei, W.; Jin, W. PDMS/Ceramic Composite Membrane for Pervaporation Separation of Acetone–Butanol–Ethanol (ABE) Aqueous Solutions and Its Application in Intensification of ABE Fermentation Process. Chem. Eng. Process. 2014, 86, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.Y.; Park, B.; Hung, F.; Sahimi, M.; Tsotsis, T.T. Design Issues of Pervaporation Membrane Reactors for Esterification. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2002, 57, 4933–4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Arias, J.D.; Dobrosz-Gómez, I.; de Lasa, H.; Gómez-García, M.-Á. Pervaporation Membrane–Catalytic Reactors for Isoamyl Acetate Production. Catalysts 2023, 13, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-F.; Zhen, P.-Y.; Wu, J.-K.; Wang, N.-X.; An, Q.-F.; Lee, K.-R. Polyelectrolyte complexes/silica hybrid hollow fiber membrane for fusel oils pervaporation dehydration processes. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 545, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, L.; Wei, G. Fabrication, Properties, Performances, and Separation Application of Polymeric Pervaporation Membranes: A Review. Polymers 2020, 12, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Guo, H.; Liang, Y. Recent Advanced Development of Acid-Resistant Thin-Film Composite Nanofiltration Membrane Preparation and Separation Performance in Acidic Environments. Separations 2023, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauwaert, J.; Van de Steene, E.; Vermeir, P.; de Clercq, J.; Thybaut, J.W. Critical Assessment of the Thermodynamics in Acidic Resin-Catalyzed Esterifications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 22079–22091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Wang, Z.; Qian, M.; Deng, Q.; Sun, P. Kinetic Aspects of Esterification and Transesterification in Microstructured Reactors. Molecules 2024, 29, 3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-García, M.-Á.; Dobrosz-Gómez, I.; Osorio-Viana, W. Experimental Assessment and Simulation of Isoamyl Acetate Production Using a Batch Pervaporation Membrane Reactor. Chem. Eng. Process. 2017, 122, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HybSi. Technology Proposition. Available online: https://www.hybsi.com/technology-proposition/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Waldburger, R.M.; Wildmer, F. Membrane reactors in chemical production processes and the application to the pervaporation-assisted esterification. Chem. Eng. Technol. 1996, 19, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Marcano, J.G.; Tsotsis, T.T. Catalytic Membranes and Membrane Reactors; Wiley-VCH GmbH: Weinheim, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kujawski, W.; Warszawski, A.; Ratajczak, W.; Porebski, T.; Capala, W.; Ostrowska, I. Removal of phenol from wastewater by different separation techniques. Desalination 2004, 163, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Viana, W.; Duque-Bernal, M.; Quintero-Arias, J.D.; Dobrosz-Gómez, I.; Fontalvo, J.; Gómez-García, M.-Á. Activity Model and Consistent Thermodynamic Features for Acetic Acid–Isoamyl Alcohol–Isoamyl Acetate–Water Reactive System. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2013, 345, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Bernal, M.; Quintero-Arias, J.D.; Osorio-Viana, W.; Dobrosz-Gómez, I.; Fontalvo, J.; Gómez-García, M.-Á. Kinetic Study on the Homogeneous Esterification of Acetic Acid with Isoamyl Alcohol. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 2013, 45, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Viana, W.; Duque-Bernal, M.; Quintero-Arias, J.D.; Dobrosz-Gómez, I.; Fontalvo, J.; Gómez-García, M.-Á. Kinetic Study on the Catalytic Esterification of Acetic Acid with Isoamyl Alcohol over Amberlite IR-120. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 101, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervatech® Datasheet Tubular Hybrid Silica HybSi® Acid Resistant Membrane. Available online: https://pervatech.com/products (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- La Rocca, T.; Carretier, E.; Dhaler, D.; Louradour, E.; Truong, T.; Moulin, P. Purification of Pharmaceutical Solvents by Pervaporation through Hybrid Silica Membranes. Membranes 2019, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Veen, H.M.; Rietkerk, M.D.A.; Shanahan, D.P.; van Tuel, M.M.A.; Kreiter, R.; Castricum, H.L.; ten Elshof, J.E.; Vente, J.F. Pushing membrane stability boundaries with HybSi® pervaporation membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 380, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, M.S.; Reddy, K.R.; Soontarapa, K.; Naveen, S.; Raghu, A.V.; Kulkarni, R.V.; Suhas, D.P.; Shetti, N.P.; Nadagouda, M.N.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Membranes for dehydration of alcohols via pervaporation. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 242, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halloub, A.; Kujawski, W. Recent Advances in Polymeric Membrane Integration for Organic Solvent Mixtures Separation: Mini-Review. Membranes 2025, 15, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemimoghadam, M.; Mohammadi, T. Evaluation of pervaporation condition and synthesis gels for NaA zeolite membranes. Desalination Water Treat. 2014, 52, 2966–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Symbol | Flux (kg m−2 h−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Acetic acid | HAc | 0.0020 |

| Isoamyl alcohol | ROH | 0.0020 |

| Isoamyl acetate | E | 0.0020 |

| Water | W | 1.8850 |

| Parameter | Units | Min. | Average | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cm2 | - | - | 55 | |

| L | 1 | 1.57 | 3.7 | |

| cm2 L−1 | 15 | 35 | 55 | |

| g L−1 | 0 | 40 | 89 | |

| % | 0 | 4.5 | 10 |

| Parameter | Value/Description |

|---|---|

| Membrane type | Hybrid silica (HybSi®, Pervatech) |

| Membrane configuration | Tubular stainless-steel support |

| Effective membrane area | 55 cm2 |

| Reactor working volume | 1.57 L |

| Operating temperature | 74 °C |

| Vacuum pressure (permeate side) | 3 mbar |

| Recirculation flow rate | 4 L·min−1 (Re ≈ 6370, fully turbulent) |

| Catalyst type | Amberlite IR-120 (H+ form) |

| Catalyst loading | 5 wt% (≈40 g L−1) |

| Water flux | 0.55–0.62 kg m−2 h−1 |

| Organic fluxes (HAc, ROH, E) | ~0.002 kg m−2 h−1 |

| Relative water selectivity () | 250–380 (peak then decreasing) |

| Permeation–Selectivity Index (PSI) | 0.45–0.72 (composition-dependent) |

| Initial water mass fraction (retentate) | ~2.8 wt% |

| Final water mass fraction (retentate) | ~0.9 wt% |

| Conversion without pervaporation | ~34–35% |

| Conversion with pervaporation | ~50% |

| Conversion enhancement | 15–20% |

| Limiting factor | Membrane area/volume ratio (≈ 35 cm2 L−1) |

| Model/experiment agreement | Good; deviations < 5–7% |

| Membrane Type | T (°C) | Water Flux (kg m−2 h−1) | Organic Flux (kg m−2 h−1) | Water/Organic Selectivity | Reported Conversion | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid silica | 70–90 | 0.4–0.7 | 0.005–0.01 | 100–500 | 40–55% | [33] |

| PVA (esterification PV) | 70–80 | 0.2–0.6 | 0.02–0.05 | 5–15 | 20–40% (with PV) | [34] |

| PDMS (alcohol–water PV) | 70 | 0.5–0.8 | 0.1–0.3 | 3–8 | – | [35] |

| Zeolite NaA | 75 | 0.05–0.15 | <0.001 | >100 | 30–60% | [36] |

| This work (HybSi®) | 74 | 0.55–0.62 | 0.0006 | ≈940 | 50% | Present study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gómez-García, M.-Á.; Dobrosz-Gómez, I.; Osorio Viana, W. Experimental and Modeling Study of a Semi-Continuous Slurry Reactor–Pervaporator System for Isoamyl Acetate Production Using a Commercial Pervaporation Membrane. Membranes 2026, 16, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010025

Gómez-García M-Á, Dobrosz-Gómez I, Osorio Viana W. Experimental and Modeling Study of a Semi-Continuous Slurry Reactor–Pervaporator System for Isoamyl Acetate Production Using a Commercial Pervaporation Membrane. Membranes. 2026; 16(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleGómez-García, Miguel-Ángel, Izabela Dobrosz-Gómez, and Wilmar Osorio Viana. 2026. "Experimental and Modeling Study of a Semi-Continuous Slurry Reactor–Pervaporator System for Isoamyl Acetate Production Using a Commercial Pervaporation Membrane" Membranes 16, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010025

APA StyleGómez-García, M.-Á., Dobrosz-Gómez, I., & Osorio Viana, W. (2026). Experimental and Modeling Study of a Semi-Continuous Slurry Reactor–Pervaporator System for Isoamyl Acetate Production Using a Commercial Pervaporation Membrane. Membranes, 16(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010025