Do Family Physicians’ Recommendations for Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccines Impact the Elderly Aged ≥60 Years? A Cross-Sectional Study in Six Chinese Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

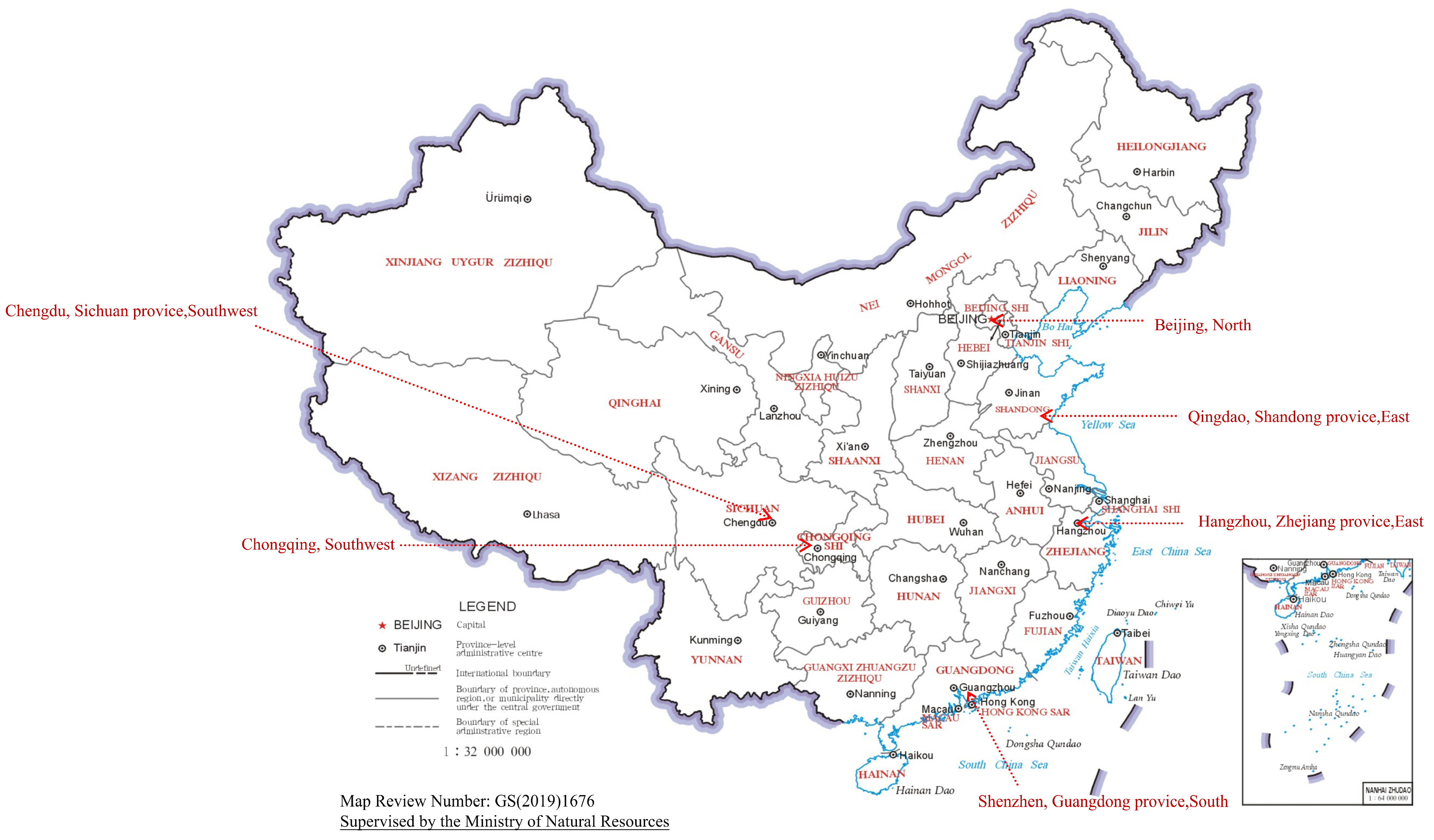

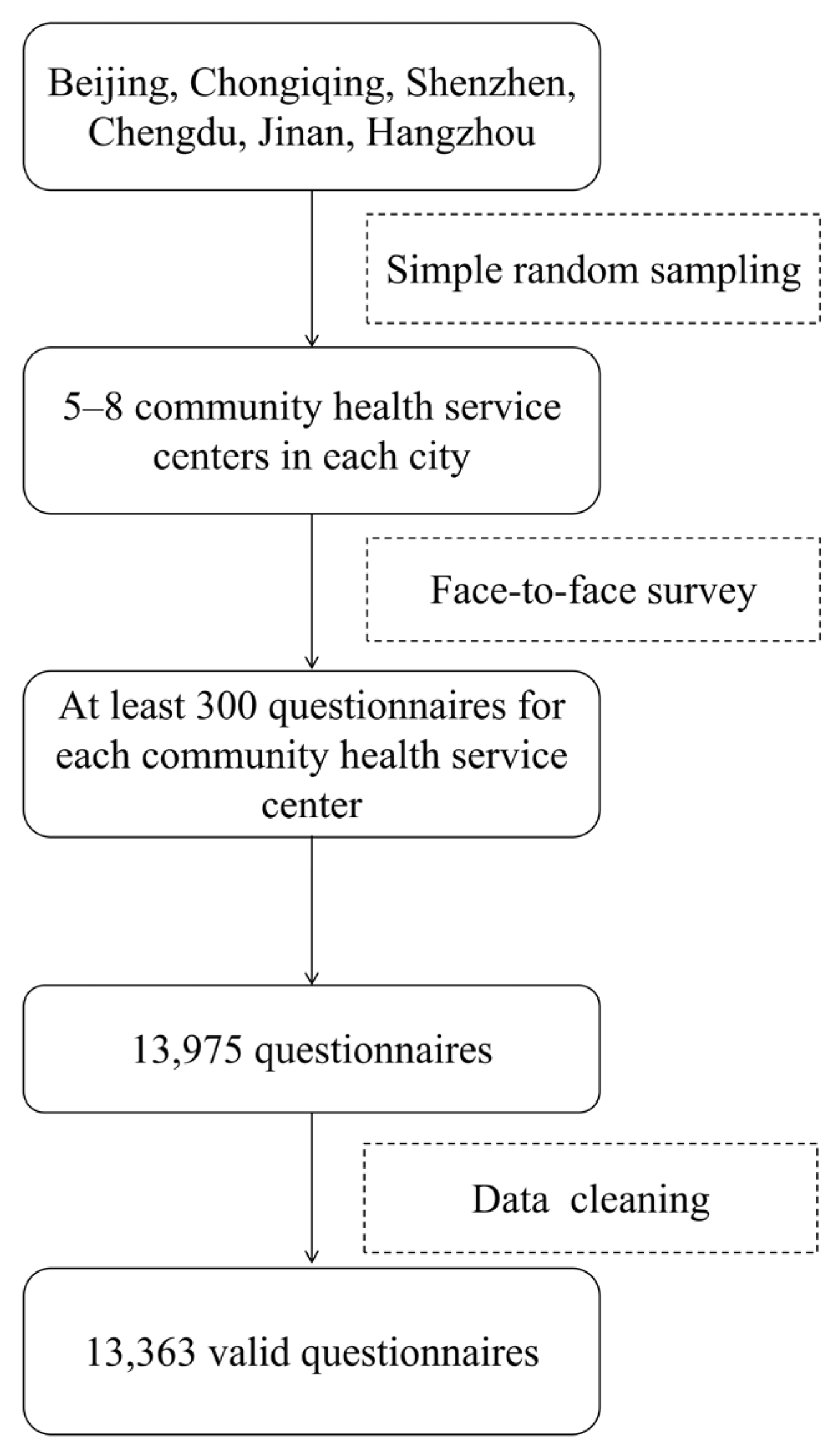

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Population Characteristics and Factors Associated with Vaccination

3.2. Analysis of Marginal Effects of Family Physicians’ Recommendations

3.3. Vaccine Policy Differences in the Probability of Influenza Vaccine and Pneumococcal Vaccine with Family Physician’s Recommendation and No Family Physician’s Recommendation

3.4. Age-Group Differences in the Probability of Influenza Vaccine and Pneumococcal Vaccine with Family Physician Recommendation and No Family Physician Recommendation

3.5. Gender Differences in the Probability of Influenza Vaccine and Pneumococcal Vaccine with Family Physician Recommendation and No Family Physician Recommendation

3.6. Monthly Income Differences in the Probability of Influenza Vaccine and Pneumococcal Vaccine with Family Physician Recommendation and No Family Physician Recommendation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Voordouw, B.C.; van der Linden, P.D.; Simonian, S.; van der Lei, J.; Sturkenboom, M.C.; Stricker, B.H. Influenza vaccination in community-dwelling elderly: Impact on mortality and influenza-associated morbidity. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003, 163, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, N.; Storch, J.; Mikolajetz, A.; Lehmann, T.; Reinhart, K.; Pletz, M.W.; Forstner, C.; Vollmar, H.C.; Freytag, A.; Fleischmann-Struzek, C. Preventive effects of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in the elderly—Results from a population-based retrospective cohort study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 1844–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorrington, M.G.; Bowdish, D.M.E. Immunosenescence and novel vaccination strategies for the elderly. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Influenza Strategy 2019–2030[EB/OL]. 15 September 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241515320 (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Al-Jumaili, A.; Dawood, H.N.; Ikram, D.; Al-Jabban, A. Pneumococcal disease: Global disease prevention strategies with a focus on the challenges in iraq. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2023, 16, 2095–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pneumococcal Disease Surveillance and Trends|Pneumococcal|CDC[EB/OL]. 9 September 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/php/surveillance/index.html (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Zhou, M.; Zhan, J.; Kong, N.; Campy, K.S.; Chen, Y. Factors associated with intention to uptake pneumococcal vaccines among Chinese elderly aged 60 years and older during the early stage of COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Health Med. 2022, 27, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunhua, B.; Peng, B.; Shuping, L.; Zheng, Z. A narrative review on vaccination rate and factors associated with the willingness to receive pneumococcal vaccine in Chinese adult population. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2139123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameli, C.; Cocchi, I.; Fumagalli, M.; Zuccotti, G. Influenza vaccination: Effectiveness, indications, and limits in the pediatric population. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Recommendations for Routine Immunization—Summary Tables [EB/OL]. 1 December 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/policies/who-recommendations-for-routine-immunization---summary-tables (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Theidel, U.; Kuhlmann, A.; Braem, A. Pneumococcal vaccination rates in adults in germany: An analysis of statutory health insurance data on more than 850,000 individuals. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2013, 110, 743–750. [Google Scholar]

- Flu Vaccination Coverage, United States, 2020–2021 Influenza Season|FluVaxView|CDC[EB/OL]. 3 September 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/fluvaxview/coverage-by-season/2020-2021.html (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Surveillance of Influenza and Other Seasonal Respiratory Viruses in the UK, Winter 2022 to 2023[EB/OL]. 29 May 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-flu-reports/surveillance-of-influenza-and-other-seasonal-respiratory-viruses-in-the-uk-winter-2022-to-2023 (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Kohlhammer, Y.; Schnoor, M.; Schwartz, M.; Raspe, H.; Schäfer, T. Determinants of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in elderly people: A systematic review. Public Health 2007, 121, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, A.; Ashur, C.; Washer, L.; Hofmann Bowman, M. Impact of the influenza vaccine on COVID-19 infection rates and severity. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelli, M.; Pignataro, G.; Gullì, A.; Nista, E.; Petrucci, M.; Saviano, A.; Marchesini, D.; Covino, M.; Ojetti, V. Effect of influenza vaccine on COVID-19 mortality: A retrospective study. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2021, 16, 1849–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.; Lyu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fang, H. PPSV-23 recommendation and vaccination coverage in China: A cross-sectional survey among healthcare workers, older adults and chronic disease patients. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2022, 21, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Atkins, K.E.; Feng, L.; Pang, M.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Cowling, B.J.; Yu, H. Seasonal influenza vaccination in China: Landscape of diverse regional reimbursement policy, and budget impact analysis. Vaccine 2016, 34, 5724–5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yang, P.; Wang, Q.; Peng, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, S.; Yi, Z.; Ying, S.; Wei, D.; et al. Influenza vaccination in preventing outbreaks in schools: A long-term ecological overview. Vaccine 2017, 35, 7133–7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principi, N.; Camilloni, B.; Esposito, S. Influenza immunization policies: Which could be the main reasons for differences among countries? Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazargan, M.; Martinez-Hollingsworth, A.; Cobb, S.; Kibe, L.W. Correlates of influenza vaccination among underserved Latinx middle-aged and older adults: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, M.; Gu, Z.; Zhou, X.; Cao, H.; Wu, F.; Liang, M.; Zheng, L.; Xian, J.; et al. Factors associated with influenza vaccination coverage and willingness in the elderly with chronic diseases in Shenzhen, China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2133912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, L.; Gu, H.; Liu, D.; Zhu, A.; Xu, H.; Hao, L.; Ye, C. Barriers to influenza vaccination among different populations in shanghai. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Yao, X.; Liu, G.; Wu, J.; Lv, M.; Pang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Huang, Y. Barriers and facilitators to uptake and promotion of influenza vaccination among health care workers in the community in Beijing, China: A qualitative study. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2202–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Commission; National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Guiding Opinions on Regulating the Management of Family Doctor Contracted Services (Document No. 35 [2018]). 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2018-12/31/content_5435461.htm (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Lu, P.J.; Srivastav, A.; Amaya, A.; Dever, J.; Roycroft, J.; Kurtz, M.; O’Halloran, A.; Williams, W. Association of provider recommendation and offer and influenza vaccination among adults aged ≥18 years—United states. Vaccine 2018, 36, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.D.; Cheng, Y.; Wong, B.; Gong, N.; Nie, J.B.; Zhu, W.; McLaughlin, M.M.; Xie, R.; Deng, Y.; Huang, M. Patient-physician mistrust and violence against physicians in Guangdong province, China: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Li, Z.; Niu, Q.; Wang, C.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Bai, Y.; Ou, L.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of the vaccination status of three non-immunization program vaccines among people aged 50 and above in Henan Province, 2020–2023. Mod. Prev. Med. 2025, 36, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Xu, E.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Du, J.; Zhang, X.; Che, X.; Gu, W. Factors associated with pneumococcal vaccination among an urban elderly population in China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2014, 10, 2994–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mui, L.W.H.; Chan, A.Y.S.; Lee, A. Cross-sectional study on attitudes among general practitioners towards pneumococcal vaccination for middle-aged and elderly population in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- State Administration of Foreign Exchange. [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.safe.gov.cn/safe/rmbhlzjj/index.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine (PPSV23)—What You Need to Know: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia[EB/OL]. 30 December 2019. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/007607.htm (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- The Weekly Epidemiological Record (WER)[EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/journals/weekly-epidemiological-record (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Influenza Infection (flu)—CDNA National Guidelines for Public Health Units [EB]; Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care: Woden, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Technical guidelines for influenza vaccination in China (2023–2024). Chin. J. Viral Dis. 2024, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Li, L.; Cao, L.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, Z. Analysis of the vaccination status of three non-immunization program vaccines among people aged ≥60 years in China, 2019–2023. Chin. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 25, 592–597. [Google Scholar]

- Al Rifai, M.; Khalid, U.; Misra, A.; Liu, J.; Nasir, K.; Cainzos-Achirica, M.; Mahtta, D.; Ballantyne, C.; Petersen, L.; Virani, S. Racial and geographic disparities in influenza vaccination in the U.S. among individuals with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: Renewed importance in the setting of COVID-19. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 5, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Outcalt, D.; Jeffcott-Pera, M.; Carter-Smith, P.; Schoof, B.K.; Young, H.F. Vaccines provided by family physicians. Ann. Fam. Med. 2010, 8, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, V.S. Physicians’ recommendation affects HPV vaccination uptake. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, e592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridda, I.; Motbey, C.; Lam, L.; Lindley, I.R.; McIntyre, P.B.; MacIntyre, C.R. Factors associated with pneumococcal immunisation among hospitalised elderly persons: A survey of patient’s perception, attitude, and knowledge. Vaccine 2008, 26, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, A.; Chanyasanha, C.; Sujirarat, D.; Matsumoto, N.; Nakazato, M. Factors associated with pneumococcal vaccination in elderly people: A cross-sectional study among elderly club members in Miyakonojo city, Japan. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launch of Influenza Vaccination in the City. [EB/OL]. 13 September 2024. Available online: https://www.beijing.gov.cn/fuwu/bmfw/sy/jrts/202409/t20240913_3865950.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Shenzhen Municipal Health Commission. [EB/OL]. 7 November 2023. Available online: https://wjw.sz.gov.cn/ztzl/ymjz/xgzc/content/post_10938913.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- de Boer, P.T.; van Werkhoven, C.H.; van Hoek, A.J.; Knol, M.J.; Sanders, E.M.; Wallinga, J.; de Melker, H.E.; Steens, A. Higher-valency pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in older adults, taking into account indirect effects from childhood vaccination: A cost-effectiveness study for the NETHERLANDS. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minghuang, J.; Pengchao, L.; Xuelin, Y.; Khezar, H.; Yilin, G.; Shan, Z.; Jin, P.; Xinke, S.; Zhaojing, P.; Yifan, H.; et al. Preference of influenza vaccination among the elderly population in Shaanxi province, China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 3119–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, M.S.; Alshehri, A.A.; Baali, F.H.; Gong, Y.; Zhu, S.; Peng, J.; Shi, X.; Pu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Fang, Y. Public perceptions and influencing factors of seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in Makkah region, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1534176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiding Opinions on Promoting the High-Quality Development of Family Doctor Contracted Services. [EB/OL]; 3 March 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-03/15/content_5679177.htm (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Briggs, L.; Fronek, P.; Quinn, V.; Wilde, T. Perceptions of influenza and pneumococcal vaccine uptake by older persons in Australia. Vaccine 2019, 37, 4454–4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Michaud, C.; Li, Z.; Dong, Z.; Sun, B.; Zhang, J.; Cao, D.; Wan, X.; Zeng, C.; Wei, B. Transformation of the education of health professionals in China: Progress and challenges. Lancet 2014, 384, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| City | Beijing | 2180 | 16.31 |

| Chengdu | 2059 | 15.41 | |

| Hangzhou | 2208 | 16.52 | |

| Qingdao | 2140 | 16.01 | |

| Shenzhen | 2253 | 16.86 | |

| Chongqing | 2523 | 18.88 | |

| Gender | Male | 6048 | 45.26 |

| Female | 7315 | 54.74 | |

| Age | 60–69 | 7678 | 57.46 |

| 70–79 | 4302 | 32.19 | |

| ≥80 | 1383 | 10.35 | |

| Ethnicity | Han | 13,073 | 97.83 |

| Minorities | 290 | 2.17 | |

| Education Level | Primary School and Below | 3720 | 27.84 |

| Junior High School | 3992 | 29.87 | |

| Senior High School | 3461 | 25.90 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 2050 | 15.34 | |

| Postgraduate | 140 | 1.05 | |

| Monthly Income (CNY *) | ≤2500 | 3850 | 28.81 |

| 2501–5000 | 5829 | 43.62 | |

| 5001–7500 | 2457 | 18.39 | |

| >7500 | 1227 | 9.18 | |

| Health Status | Very Poor | 215 | 1.61 |

| Poor | 1188 | 8.89 | |

| Fair | 5367 | 40.16 | |

| Good | 5421 | 40.57 | |

| Very Good | 1172 | 8.77 | |

| Vaccine Price (Influenza Vaccination) | Self-pay | 8813 | 65.95 |

| Free | 4550 | 34.05 | |

| Vaccine Price (Pneumococcal Vaccination) | Self-pay | 10,317 | 77.21 |

| Free | 3046 | 22.79 | |

| Vaccine Uptake (Influenza Vaccination) | No | 8813 | 65.95 |

| Yes | 4550 | 34.05 | |

| Vaccine Uptake (Pneumococcal Vaccination) | No | 10,317 | 77.21 |

| Yes | 3046 | 22.79 | |

| Family Physician Vaccination Recommendation (Influenza Vaccination) | No | 6845 | 51.22 |

| Yes | 6518 | 48.78 | |

| Family Physician Vaccination Recommendation (Pneumococcal Vaccination) | No | 9546 | 71.44 |

| Yes | 3817 | 28.56 | |

| Variable | Influenza Vaccine | Pneumococcal Vaccine | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Vaccinated | Vaccinated | p-Value | χ2 | Non-Vaccinated | Vaccinated | p-Value | χ2 | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||||

| City | Beijing | 1472 (67.52%) | 708 (32.48%) | <0.001 | 187.684 | 1659 (76.10%) | 521 (23.90%) | <0.001 | 271.66 |

| Chengdu | 1414 (68.67%) | 645 (31.33%) | 1367 (66.39%) | 692 (33.61%) | |||||

| Hangzhou | 1195 (54.12%) | 1013 (45.88%) | 1655 (74.95%) | 553 (25.05%) | |||||

| Qingdao | 1540 (71.96%) | 600 (28.04%) | 1637 (76.50%) | 503 (23.50%) | |||||

| Shenzhen | 1470 (65.25%) | 783 (34.75%) | 1934 (85.84%) | 319 (14.16%) | |||||

| Chongqing | 1722 (68.25%) | 801 (31.75%) | 2065 (81.85%) | 458 (18.15%) | |||||

| Gender | Male | 3938 (65.11%) | 2110 (34.89%) | 0.063 | 3.458 | 4635 (76.64%) | 1413 (23.36%) | 0.154 | 2.031 |

| Female | 4875 (66.64%) | 2440 (33.36%) | 5682 (77.68%) | 1633 (22.32%) | |||||

| Age | 60–69 | 5038 (65.62%) | 2640 (34.38%) | 1.383 | 0.501 | 5929 (77.22%) | 1749 (22.78%) | 0.318 | 2.289 |

| 70–79 | 2846 (66.16%) | 1456 (33.84%) | 3300 (76.71%) | 1002 (23.29%) | |||||

| ≥80 | 929 (67.17%) | 454 (32.83%) | 1088 (78.67%) | 295 (21.33%) | |||||

| Ethnicity | Han Chinese | 8628 (66.00%) | 4445 (34.00%) | 0.433 | 0.007 | 10,100 (77.26%) | 2973 (22.74%) | 0.329 | 0.953 |

| Minorities | 185 (63.79%) | 105 (36.21%) | 217 (74.83%) | 73 (25.17%) | |||||

| Education Level | Primary School and Below | 2677 (71.96%) | 1043 (28.04%) | <0.001 | 99.695 | 2972 (79.89%) | 748 (20.11%) | <0.001 | 59.038 |

| Junior High School | 2609 (65.36%) | 1383 (34.64%) | 3100 (77.66%) | 892 (22.34%) | |||||

| Senior High School | 2205 (63.71%) | 1256 (36.29%) | 2680 (77.43%) | 781 (22.57%) | |||||

| Bachelor’s Degree | 1243 (60.63%) | 807 (39.37%) | 1472 (71.80%) | 578 (28.20%) | |||||

| Postgraduate | 79 (56.43%) | 61 (43.57%) | 93 (66.43%) | 47 (33.57%) | |||||

| Monthly Income (CNY) | ≤2500 | 2849 (74.00%) | 1001 (26.00%) | <0.001 | 157.152 | 3095 (80.39%) | 755 (19.61%) | <0.001 | 36.476 |

| 2501—5000 | 3676 (63.06%) | 2153 (36.94%) | 4458 (76.48%) | 1371 (23.52%) | |||||

| 5001—7500 | 1520 (61.86%) | 937 (38.14%) | 1824 (74.24%) | 633 (25.76%) | |||||

| ≥7500 | 768 (62.59%) | 459 (37.41%) | 940 (76.61%) | 287 (23.39%) | |||||

| Health Status | Very Poor | 125 (58.14%) | 90 (41.86%) | 0.004 | 15.594 | 132 (61.40%) | 83 (38.60%) | <0.001 | 52.851 |

| Poor | 813 (68.43%) | 375 (31.57%) | 954 (80.30%) | 234 (19.70%) | |||||

| Fair | 3599 (67.06%) | 1768 (32.94%) | 4214 (78.52%) | 1153 (21.48%) | |||||

| Good | 3519 (64.91%) | 1902 (35.09%) | 4157 (76.68%) | 1264 (23.32%) | |||||

| Very Good | 757 (64.59%) | 415 (35.41%) | 860 (73.38%) | 312 (26.62%) | |||||

| Family Physician Vaccination Recommendation | No | 5405 (78.96%) | 1440 (21.04%) | <0.001 | 1058.091 | 8145 (85.32%) | 1401 (14.68%) | <0.001 | 1251.479 |

| Yes | 3408 (52.29%) | 3110 (47.71%) | 2172 (56.90%) | 1645 (43.10%) | |||||

| Vaccine Price | Self-pay | 5871 (66.62%) | 2942 (33.38%) | 0.476 | 0.509 | 4279 (41.48%) | 6038 (58.52%) | 0.445 | 0.584 |

| Free | 3059 (67.23%) | 1491 (32.77%) | 1287 (42.25%) | 1759 (57.75%) | |||||

| Family Physician Recommendation | Vaccine Price | Influenza Vaccine | Pneumococcal Vaccine | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||||||||||

| Vaccinated (%) | p-Value | Vaccinated (%) a | Effect of Vaccine Price by Family Physician Recommendation (pp) b | 95% CI | Effect of Physician Family Recommendation by Vaccine Price (pp) c | 95% CI | Vaccinated (%) | p-Value | Vaccinated (%) a | Effect of Vaccine Price by Family Physician Recommendation (pp) b | 95% CI | Effect of Family Physician Recommendation by Vaccine Price (pp) c | 95% CI | ||

| No | Self-pay | 18.50% | <0.001 | 19.89% | reference | reference | 14.90% | 0.622 | 14.38% | reference | reference | ||||

| Free | 24.40% | 21.53% | 1.64% | (0.002,0.031) * | reference | 14.50% | 14.53% | 0.15% | (−0.010, 0.011) | reference | |||||

| Yes | Self-pay | 46.50% | <0.001 | 47.36% | reference | 27.47% | (0.259, 0.290) * | 41.60% | 0.103 | 43.16% | reference | 28.78% | (0.266, 0.304) * | ||

| Free | 51.70% | 49.86% | 2.50% | (0.003,0.047) * | 28.33% | (0.265, 0.301) * | 44.30% | 43.44% | 0.28% | (−0.019, 0.023) | 28.91% | (0.267, 0.305) * | |||

| Family Physician Recommendation | Age | Influenza Vaccine | Pneumococcal Vaccine | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||||||||||

| Vaccinated (%) | p-Value | Vaccinated (%) a | Effect of Age by Family Physician Recommendation (pp) b | 95% CI | Effect of Family Physician Recommendation by Age (pp) c | 95% CI | Vaccinated (%) | p-Value | Vaccinated (%) a | Effect of Age by Family Physician Recommendation (pp) b | 95% CI | Effect of Family Physician Recommendation by Age (pp) c | 95% CI | ||

| No | 60–69 | 19.70% | 0.004 | 21.37% | reference | reference | 14.20% | 0.025 | 14.12% | reference | reference | ||||

| 70–79 | 23.30% | 22.28% | 0.91% | (−0.005,0.024) | reference | 16.00% | 15.41% | 1.29% | (0.001,0.025) * | reference | |||||

| ≥80 | 20.90% | 20.47% | −0.90% | (−0.030,0.013) | reference | 13.10% | 13.93% | −0.19% | (−0.020,0.016) | reference | |||||

| Yes | 60–69 | 49.30% | 0.004 | 49.48% | reference | 28.11% | (0.267, 0.300) * | 43.60% | 0.643 | 42.68% | reference | 28.56% | (0.267, 0.304) * | ||

| 70–79 | 46.30% | 50.81% | 1.33% | (−0.008,0.034) | 28.53% | (0.270, 0.305) * | 42.70% | 45.21% | 2.53% | (0.002,0.049) * | 29.80% | (0.277, 0.317) * | |||

| ≥80 | 43.30% | 48.12% | −1.36% | (−0.046,0.019) | 27.65% | (0.260, 0.298) * | 41.30% | 42.30% | −0.38% | (0.033,0.838) * | 28.37% | (0.277, 0.317) * | |||

| Family Physician Recommendation | Gender | Influenza Vaccine | Pneumococcal Vaccine | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||||||||||

| Vaccinated (%) | p-Value | Vaccinated (%) a | Effect of Gender by Family Physician Recommendation (pp) b | 95% CI | Effect of Family Physician Recommendation by Gender (pp) c | 95% CI | Vaccinated (%) | p-Value | Vaccinated (%) a | Effect of Gender by Family Physician Recommendation (pp) b | 95% CI | Effect of Family Physician Recommendation by Gender (pp) c | 95% CI | ||

| No | Male | 20.30% | 0.188 | 19.72% | reference | reference | 14.50% | 0.651 | 14.48% | reference | reference | ||||

| Female | 21.60% | 20.02% | 0.30% | (−0.009, 0.015) | reference | 14.80% | 14.56% | 0.08% | (−0.010, 0.012) | reference | |||||

| Yes | Male | 49.10% | 0.029 | 47.11% | reference | 27.39% | (0.262, 0.296) * | 44.40% | 0.114 | 43.36% | reference | 28.88% | (0.270, 0.306) * | ||

| Female | 46.40% | 47.57% | 0.46% | (−0.014, 0.024) | 27.55% | (0.264, 0.298) * | 41.90% | 43.51% | 0.15% | (−0.020, 0.023) | 28.95% | (0.271, 0.307) * | |||

| Family Physician Recommendation | Monthly Income (CNY) | Influenza Vaccine | Pneumococcal Vaccine | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||||||||||

| Vaccinated (%) | p-Value | Vaccinated (%) a | Effect of Monthly Income by Family Physician Recommendation (pp) b | 95% CI | Effect of Family Physician Recommendation by Monthly Income (pp) c | 95% CI | Vaccinated (%) | p-Value | Vaccinated (%) a | Effect of Monthly Income by Family Physician Recommendation (pp) b | 95% CI | Effect of Family Physician Recommendation by Monthly Income (pp) c | 95% CI | ||

| No | <2500 | 13.70% | <0.001 | 15.83% | reference | reference | 13.23% | <0.001 | 12.25% | reference | reference | ||||

| 2500–5000 | 22.10% | 21.37% | 5.54% | (0.041, 0.070) * | reference | 14.06% | 14.41% | 2.16% | (0.010,0.034) * | reference | |||||

| 5000–7500 | 25.70% | 22.36% | 6.53% | (0.044, 0.087) * | reference | 16.09% | 18.08% | 5.83% | (0.042,0.075) * | reference | |||||

| >7500 | 29.30% | 20.16% | 4.33% | (0.016, 0.070) * | reference | 13.28% | 16.23% | 3.98% | (0.019,0.061) * | reference | |||||

| Yes | <2500 | 40.00% | <0.001 | 40.39% | reference | 24.56% | (0.232, 0.266) * | 40.92% | <0.001 | 38.54% | reference | 27.69% | (0.256, 0.297) * | ||

| 2500–5000 | 50.10% | 49.48% | 9.09% | (0.067, 0.115) * | 28.11% | (0.267, 0.300) * | 42.62% | 43.06% | 4.52% | (0.020,0.070) * | 28.56% | (0.267, 0.304) * | |||

| 5000–7500 | 54.00% | 50.92% | 10.53% | (0.072, 0.139) * | 28.56% | (0.270, 0.306) * | 46.55% | 49.79% | 11.25% | (0.082,0.144) * | 30.46% | (0.282, 0.326) * | |||

| >7500 | 47.20% | 47.63% | 7.24% | (0.029, 0.116) * | 27.47% | (0.258, 0.297) * | 41.01% | 46.53% | 7.99% | (0.040,0.120) * | 27.73% | (0.250, 0.304) * | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Dai, J.; Yuan, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Liu, G.; Zeng, Q.; Qiu, Q.; Luo, C.; et al. Do Family Physicians’ Recommendations for Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccines Impact the Elderly Aged ≥60 Years? A Cross-Sectional Study in Six Chinese Cities. Vaccines 2025, 13, 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13080886

Wang Y, Dai J, Yuan S, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Zhu L, Liu G, Zeng Q, Qiu Q, Luo C, et al. Do Family Physicians’ Recommendations for Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccines Impact the Elderly Aged ≥60 Years? A Cross-Sectional Study in Six Chinese Cities. Vaccines. 2025; 13(8):886. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13080886

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yuxing, Jianing Dai, Shuai Yuan, Ying Chen, Zhujiazi Zhang, Ling Zhu, Gang Liu, Qiang Zeng, Qian Qiu, Chunyu Luo, and et al. 2025. "Do Family Physicians’ Recommendations for Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccines Impact the Elderly Aged ≥60 Years? A Cross-Sectional Study in Six Chinese Cities" Vaccines 13, no. 8: 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13080886

APA StyleWang, Y., Dai, J., Yuan, S., Chen, Y., Zhang, Z., Zhu, L., Liu, G., Zeng, Q., Qiu, Q., Luo, C., Deng, R., & You, L. (2025). Do Family Physicians’ Recommendations for Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccines Impact the Elderly Aged ≥60 Years? A Cross-Sectional Study in Six Chinese Cities. Vaccines, 13(8), 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13080886