Retrospective Analysis of HPV Vaccination Attitudes and Uptake Among Medical Students: Implications for Preventive Healthcare

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Setting

2.2. Questionnaire Development and Validation

2.3. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Concerns

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

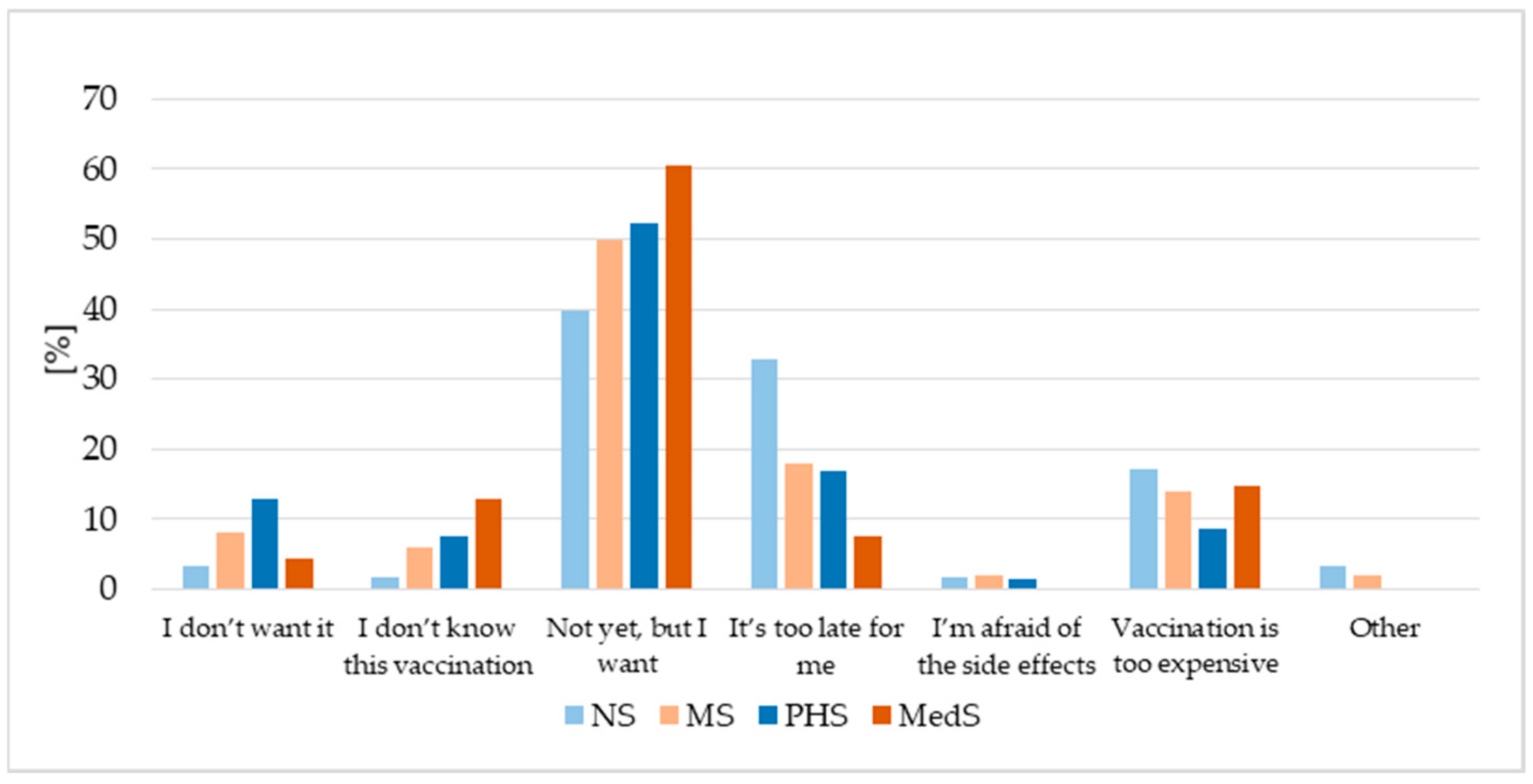

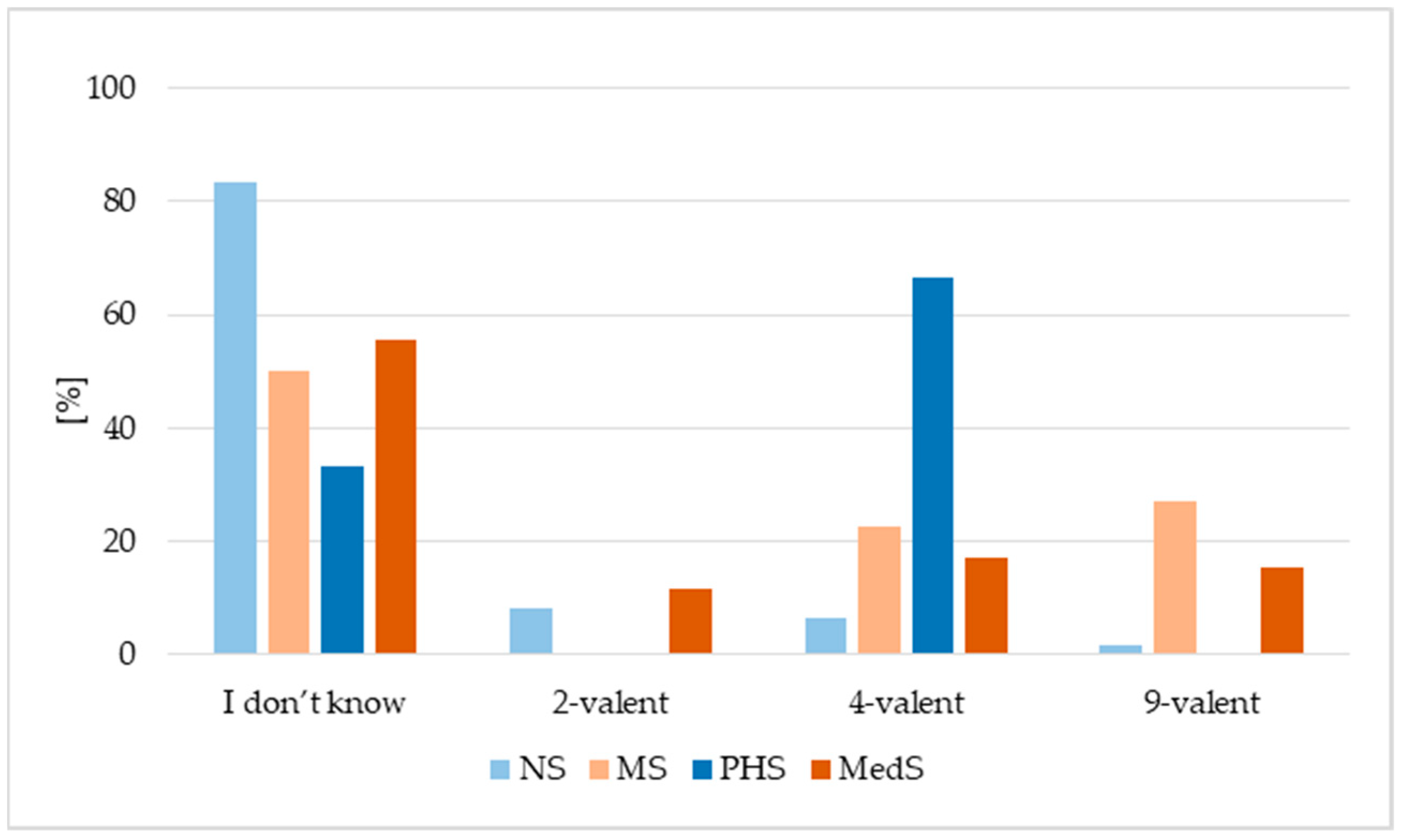

3.2. HPV Vaccination Status

3.3. Age at First Dose of HPV Vaccine

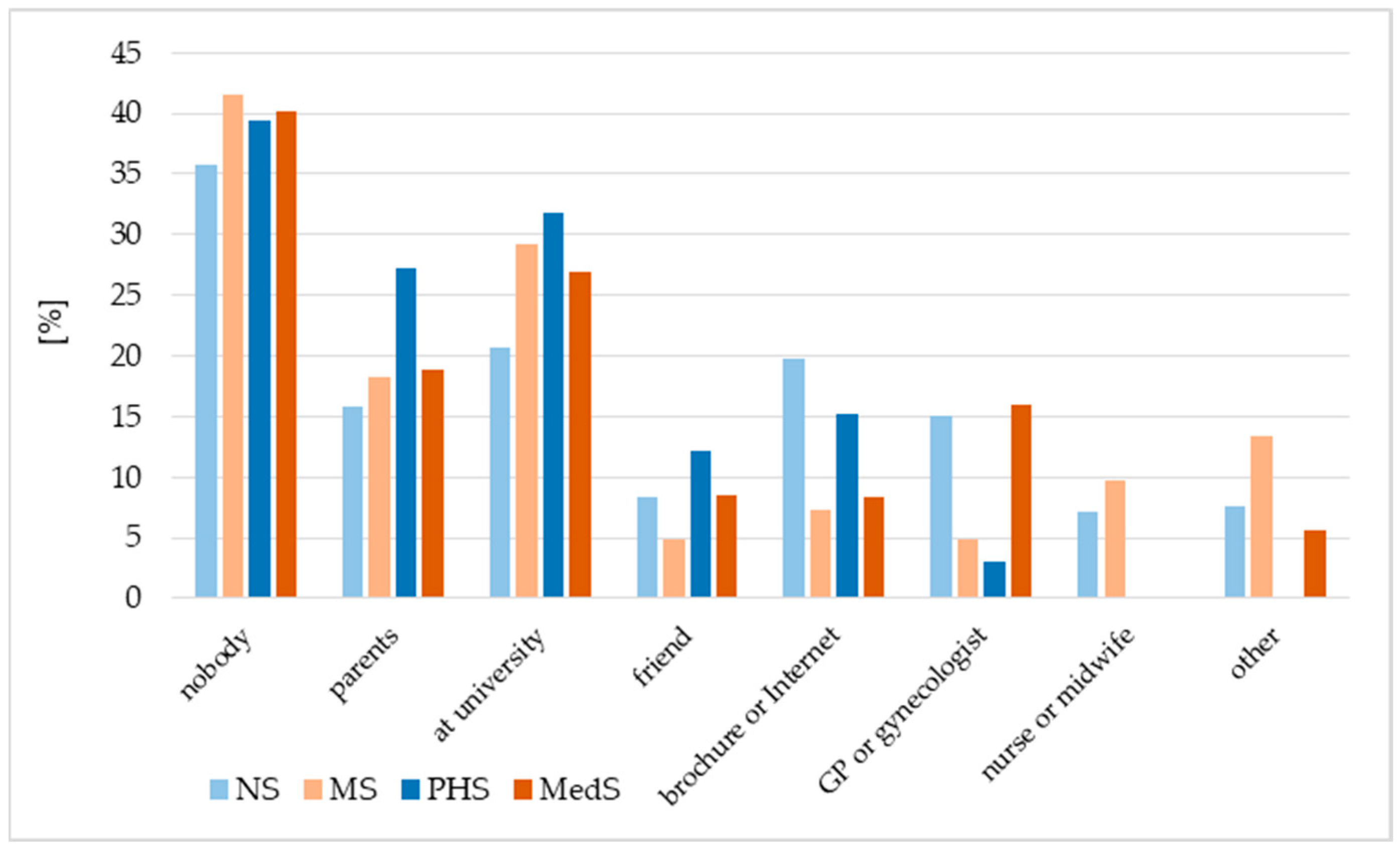

3.4. Information Source on HPV Vaccination

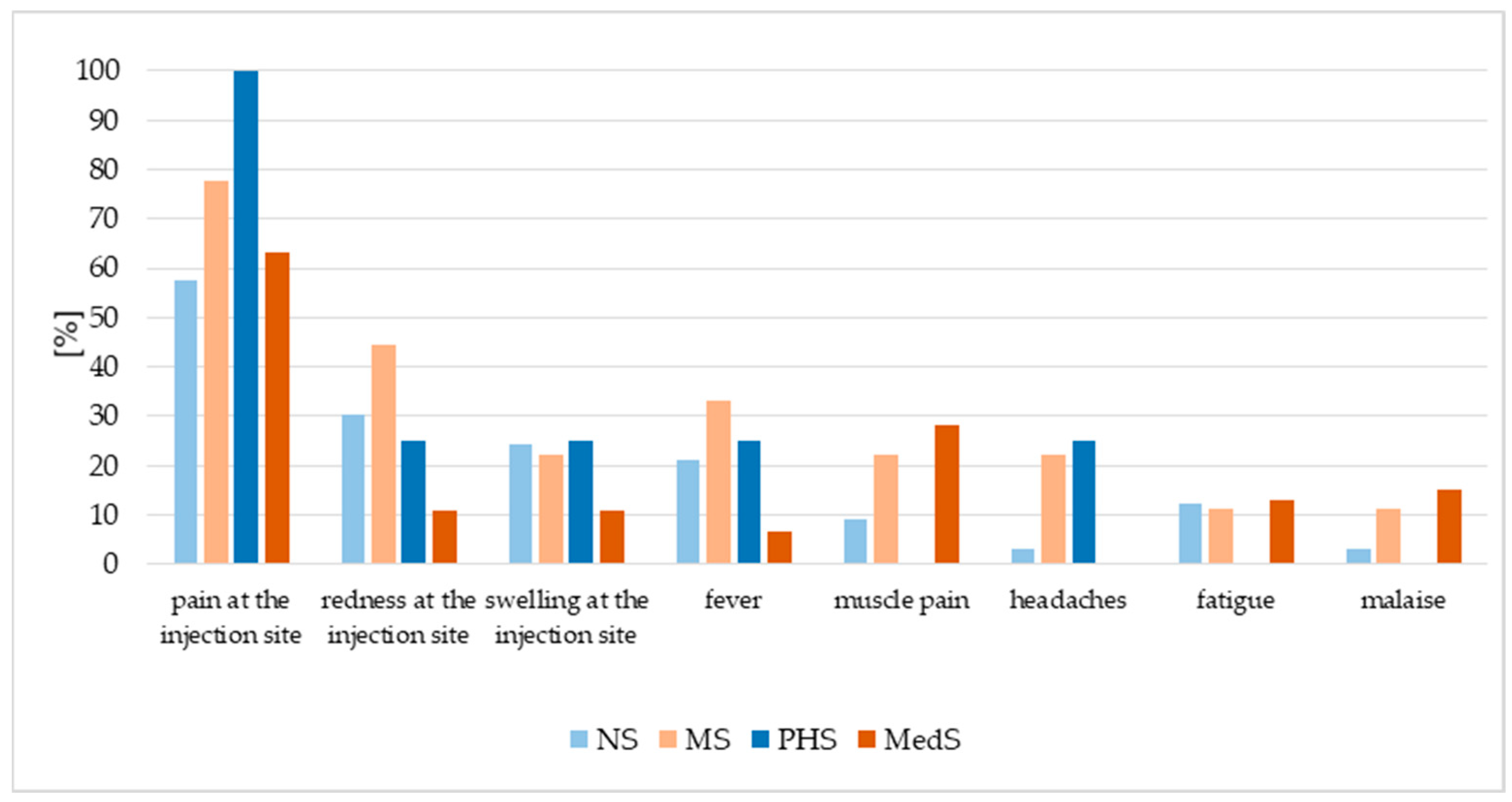

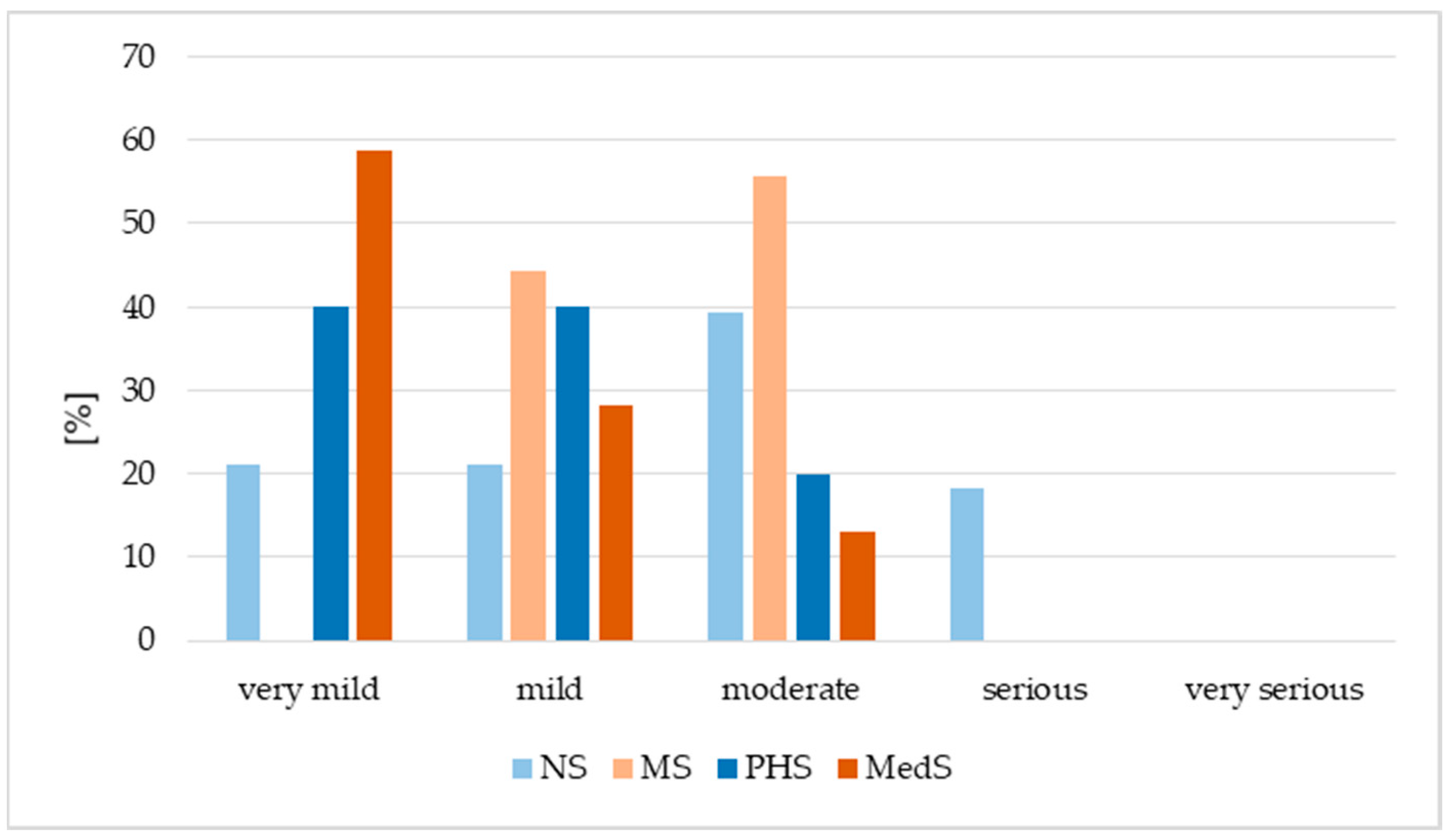

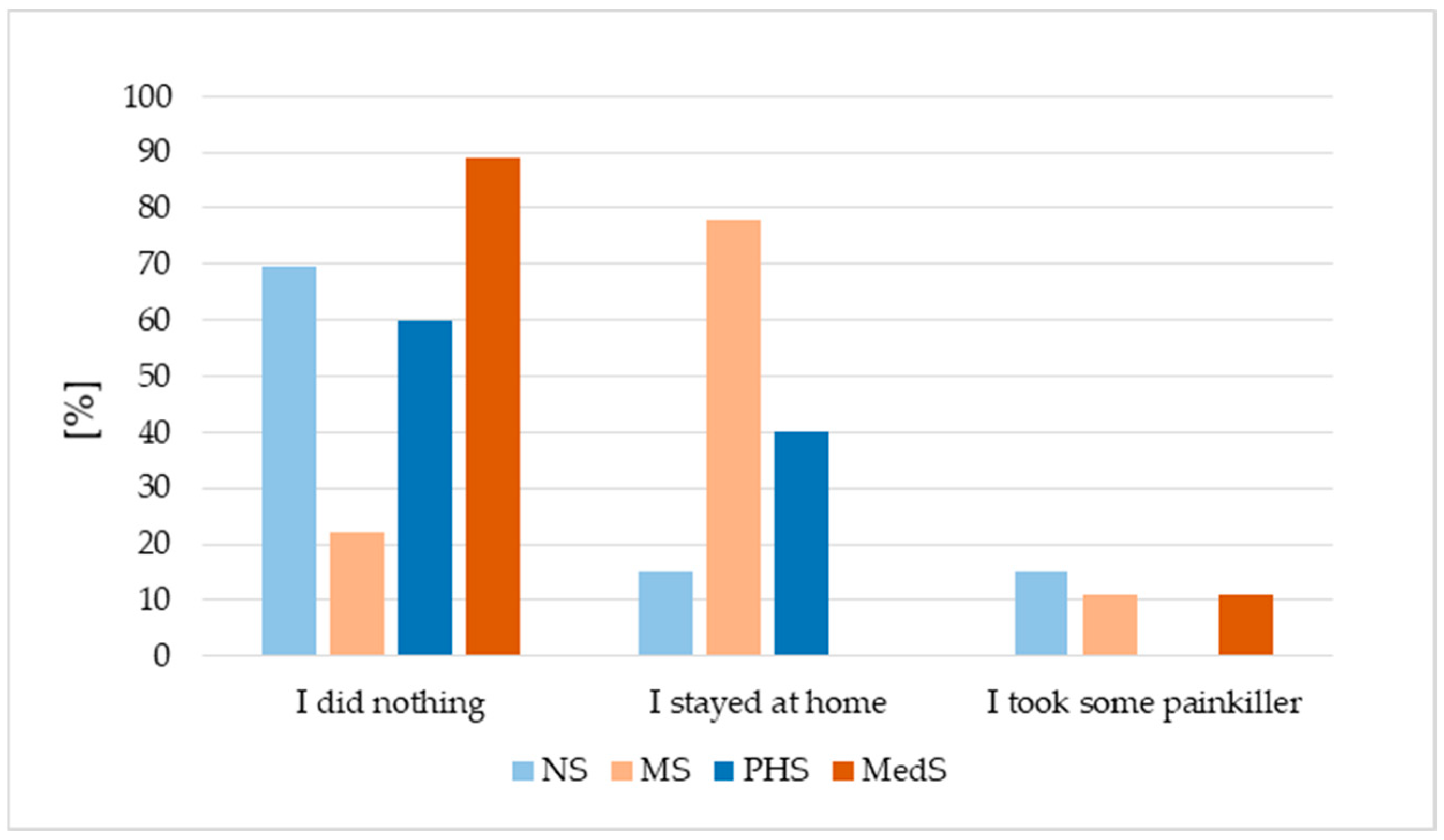

3.5. HPV Vaccination Adverse Events and Future Vaccination Intentions

3.6. Factors Associated with HPV Vaccination Status

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dufour, L.; Carrouel, F.; Dussart, C. Human Papillomaviruses in Adolescents: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Pharmacists Regarding Virus and Vaccination in France. Viruses 2023, 15, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunade, K.S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 40, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Factsheet About Human Papillomavirus. 2018. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/human-papillomavirus/factsheet (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Seweryn, M.; Leszczyńska, A.; Jakubowicz, J.; Banaś, T. Cervical cancer in Poland—Epidemiology, prevention, and treatment pathways. Oncol. Clin. Pract. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikala, M.; Burzyńska, M. Trends in mortality due to malignant neoplasms of female genital organs in Poland in the period 2000–2021—A population-based study. Cancers 2024, 16, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Sherrah, M.; Sultana, F.; Castle, P.E.; Arbyn, M.; Gertig, D.; Caruana, M.; Wrede, C.D.; Saville, M.; Canfell, K. National experience in the first two years of primary human papillomavirus (HPV) cervical screening in an HPV vaccinated population in Australia: Observational study. BMJ 2022, 376, e068582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L.; Saura-Lázaro, A.; Montoliu, A.; Brotons, M.; Alemany, L.; Diallo, M.S.; Afsar, O.Z.; LaMontagne, O.S.; Mosina, L.; Contreras, M.; et al. HPV vaccination introduction worldwide and WHO and UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage 2010–2019. Prev. Med. 2021, 144, 106399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minister of Health. Regulation of the Minister of Health of 16 September 2010 on the List of Recommended Protective Vaccinations and the Method of Financing and Documenting Recommended Protective Vaccinations Required by International Health Regulations 2010. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20101801215 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Ministry of Health, Poland. HPV Vaccination Guidelines. Gov.pl. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/zdrowie/hpv (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Kałucka, S.; Kusideł, E.; Głowacka, A.; Oczoś, P.; Grzegorczyk-Karolak, I. Pre-vaccination stress, post-vaccination adverse reactions, and attitudes towards vaccination after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine among health care workers. Vaccines 2022, 10, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattray, J.; Jones, M.C. Essential elements of questionnaire design and development. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem. 2020. Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/4e245e89-ddcc-488f-97c7-9de5e08524ef/content (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance. Annual Immunisation Coverage Report 2023—Summary. NCIRS, 2024. Available online: https://ncirs.org.au/immunisation-coverage-data-and-reports/annual-immunisation-coverage-report-2023-summary (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Borowska, M.; Koczkodaj, P.; Mańczuk, M. HPV vaccination coverage in the European Region. Nowotw. J. Oncol. 2024, 74, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Guidance on HPV Vaccination in EU Countries: Focus on Boys, People Living with HIV and 9-Valent HPV Vaccine Introduction. ECDC, Stockholm, 2020. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/guidance-hpv-vaccination-eu-focus-boys-people-living-hiv-9vHPV-vaccine (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Han, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Cai, R.; Li, M.; Dai, Y.; Dang, L.; Chen, H.; et al. Global HPV vaccination programs and coverage rates: A systematic review. eClinicalMedicine 2025, 84, 103290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhao, D.; Zi, T.; Huang, R.; Zhao, F.; Li, L.; Zheng, J.; Wang, L. Evolving trends in HPV vaccination coverage among women aged 9–45 in Chengdu, China: Insights from 2017 to 2023. Vaccine 2025, 62, 127579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Speech by Naomi Kitahara, UNFPA Representative in Viet Nam, at the Workshop to Launch the Results of the Investment Case Study on HPV Vaccination in Viet Nam. UNFPA, Viet Nam, 2021. Available online: https://vietnam.unfpa.org/en/news/speech-naomi-kitahara-unfpa-representative-viet-nam-workshop-launch-results-investment-case (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Yap, J.; Satria, F.B.; Alona, I.; Siregar, I.M.; Chen, S.; Yung, C.F.; Davis, C.; Lubis, I.N.D.; Tang, S. Challenges in expanding access to the HPV vaccine among schooling girls: A mixed-methods study from Indonesia. Vaccines 2025, 13, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorelli, C.; Pennisi, F.; D’Amelio, A.C.; Conversano, M.; Cinquetti, S.; Blandi, L.; Rezza, G. Vaccinating in different settings: Best practices from Italian regions. Vaccines 2025, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drejza, M.; Rylewicz, K.; Lewandowska, M.; Gross-Tyrkin, K.; Łopiński, G.; Barwińska, J.; Majcherek, E.; Szymuś, K.; Klein, P.; Plagens-Rotman, K.; et al. HPV vaccination among Polish adolescents—Results from POLKA 18 study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meites, E.; Szilagyi, P.G.; Chesson, H.W.; Unger, E.R.; Romero, J.R.; Markowitz, L.E. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination for adults: Updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, C.; Brotherton, J.M.; Pillsbury, A.; Jayasinghe, S.; Donovan, B.; Macartney, K.; Marshall, H. The impact of 10 years of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in Australia: What additional disease burden will a nonavalent vaccine prevent? Eurosurveillance 2018, 23, 1700737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colzani, E.; Johansen, K.; Johnson, H.; Celentano, L.P. Human papillomavirus vaccination in the European Union/European Economic Area and globally: A moral dilemma. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2001659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). The HPV Vaccine: Access and Use in the U.S. KFF, 2024. Available online: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/the-hpv-vaccine-access-and-use-in-the-u-s/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Evidence to Recommendations for HPV Vaccination of Adults, Ages 27 through 45 Years: ACIP Evidence-to-Recommendations Framework. CDC, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/acip/evidence-to-recommendations/HPV-adults-etr.html (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Smith, P.J.; Kennedy, A.M.; Wooten, K.; Gust, D.A.; Pickering, L.K. Association between health care providers’ influence on parents who have concerns about vaccine safety and vaccination coverage. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e1287–e1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Hu, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, M.; Xuejie, Z.; Xueqiong, Z. Human papillomavirus DNA in surgical smoke during cervical loop electrosurgical excision procedures and its impact on the surgeon. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 3643–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, J.; Ross, L. Vaccinating providers for HPV due to transmission risk in ablative dermatology procedures. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2023, 16, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Tu, Q.; Zhu, X. Prevalence of HPV infections in surgical smoke exposed gynecologists. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2021, 94, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, B.A.; Nonzee, N.J.; Tieu, L.; Pedone, B.; Cowgill, B.O.; Bastani, R. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in the transition between adolescence and adulthood. Vaccine 2021, 39, 3435–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, B.; Brotons, M.; Bosch, F.X.; Bruni, L. Epidemiology and burden of HPV-related disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 47, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.K.; Cobucci, R.N.; Rodrigues, H.M.; de Melo, A.G.; Giraldo, P.C. Safety, tolerability and side effects of human papillomavirus vaccines: A systematic quantitative review. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 18, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raethke, M.; Gorter, J.; Kalf, R.; van Balveren, L.; Jajou, R.; van Hunsel, F. Frequency, timing, burden and recurrence of adverse events following immunization after HPV vaccine based on a cohort event monitoring study in the Netherlands. Vaccines 2025, 13, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavonen, J.; Jenkins, D.; Bosch, F.X.; Naud, P.; Salmerón, J.; Wheeler, C.M.; Chow, S.N.; Apter, D.L.; Kitchener, H.C.; Castellsague, X.; et al. HPV PATRICIA study group. Efficacy of a prophylactic adjuvanted bivalent L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: An interim analysis of a phase III double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007, 369, 2161–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhazmi, A.; Alamer, E.; Daws, D.; Hakami, M.; Darraj, M.; Abdelwahab, S.; Maghfuri, A.; Algaissi, A. Evaluation of side effects associated with COVID-19 vaccines in Saudi Arabia. Vaccines 2021, 9, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kałucka, S.; Grzegorczyk-Karolak, I. Barriers associated with the uptake ratio of seasonal flu vaccine and ways to improve influenza vaccination coverage among young health care workers in Poland. Vaccines 2021, 9, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosky, E.; Bocchini Jr, J.A.; Hariri, S.; Chesson, H.; Curtis, C.R.; Saraiya, M.; Unger, E.R.; Markowitz, L.E. Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: Updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015, 64, 300–304. [Google Scholar]

- Elfström, K.M.; Lazzarato, F.; Franceschi, S.; Dillner, J.; Baussano, I. Human papillomavirus vaccination of boys and extended catch-up vaccination: Effects on the resilience of programs. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althubaiti, A. Information bias in health research: Definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2016, 9, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NS n = 252 | MS n = 82 | PHS n = 66 | MedS n = 662 | Total n = 1062 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| female | 239 (94.84%) | 82 (100.00%) | 54 (81.82%) | 401 (60.57%) | 776 (73.07%) |

| male | 11 (4.37%) | 0 (0.00%) | 12 (18.18%) | 261 (39.43%) | 284 (26.76%) |

| other | 2 (0.79%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (0.19%) |

| Mean age | 22.84 ± 2.58 | 22.26 ± 1.88 | 22.43 ± 1.42 | 22.88 ± 1.94 | 22.79 ± 2.09 |

| Years of work in the profession | |||||

| up to 5 years | 67 (26.59%) | 35 (42.68%) | 5 (7.58%) | 18 (2.72%) | 125 (11.77%) |

| 5–10 years | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 4 (0.60%) | 4 (0.38%) |

| over 10 years | 4 (1.59%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 4 (0.38%) |

| I’m just learning | 181 (71.83%) | 47 (57.32%) | 61 (92.42%) | 640 (96.68%) | 929 (87.48%) |

| Workplace | |||||

| Hospital | 61 (24.21%) | 29 (35.37%) | 1 (1.52%) | 14 (2.11%) | 105 (9.89%) |

| Clinic | 8 (3.17%) | 5 (6.10%) | 4 (6.06%) | 4 (0.60%) | 21 (1.98%) |

| Hospital Emergency Ward | 2 (0.79%) | 1 (1.22%) | 0 (0.00%) | 4 (0.60%) | 7 (0.66%) |

| Not working | 181 (71.83%) | 47 (57.32%) | 61 (92.42%) | 640 (96.68%) | 929 (87.48%) |

| Place of residence | |||||

| Village | 62 (24.60%) | 19 (23.17%) | 13 (19.7%) | 144 (21.75%) | 238 (22.41%) |

| Small city | 48 (19.05%) | 11 (13.41%) | 23 (34.85%) | 129 (19.49%) | 211 (19.87%) |

| Large city | 142 (56.35%) | 52 (63.41%) | 30 (45.45%) | 389 (58.76%) | 613 (57.72%) |

| Mother with medical education | |||||

| Yes | 60 (23.81%) | 12 (14.63%) | 11 (16.67%) | 163 (24.62%) | 246 (23.16%) |

| No | 190 (75.40%) | 69 (84.15%) | 54 (81.82%) | 495 (74.77%) | 808 (76.08%) |

| I do not know | 2 (0.79%) | 1 (1.22%) | 1 (1.52%) | 4 (0.60%) | 8 (0.75%) |

| Father with medical education | |||||

| Yes | 10 (3.97%) | 3 (3.66%) | 1 (1.52%) | 85 (12.84%) | 99 (9.32%) |

| No | 236 (93.65%) | 78 (95.12%) | 64 (96.97%) | 564 (85.2%) | 942 (88.70%) |

| I do not know | 6 (2.38%) | 1 (1.22%) | 1 (1.52%) | 13 (1.96%) | 21 (1.98%) |

| Marital status: | |||||

| Single | 239 (94.84%) | 77 (93.90%) | 58 (87.88%) | 646 (97.58%) | 1020 (96.05%) |

| Married | 13 (5.16%) | 5 (6.10%) | 8 (12.12%) | 16 (2.42%) | 42 (3.95%) |

| Divorced | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Widow/widower | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Currently in a relationship | |||||

| Yes | 179 (71.03%) | 49 (59.79%) | 44 (66.67%) | 313 (47.28%) | 585 (55.08%) |

| No | 73 (28.97%) | 33 (40.24%) | 22 (33.33%) | 349 (52.72%) | 477 (44.92%) |

| After sexual initiation | |||||

| Yes | 214 (84.92%) | 61 (74.39%) | 55 (83.33%) | 483 (72.96%) | 813 (76.55%) |

| No | 38 (15.08%) | 21 (25.61%) | 11 (16.67%) | 179 (27.04%) | 249 (23.45%) |

| With children | |||||

| Yes | 26 (10.32%) | 4 (4.88%) | 0 (0.00%) | 16 (2.42%) | 46 (4.33%) |

| No | 226 (89.69%) | 78 (95.12%) | 66 (100%) | 646 (97.58%) | 1016 (95.67%) |

| Vaccinated | NS n = 252 | MS n = 82 | PHS n = 66 | MedS n = 662 | Total n = 1062 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 61 (24.21%) | 22 (26.83%) | 15 (22.73%) | 111 (16.77%) | 209 (19.68%) |

| No | 191 (75.79%) | 60 (73.17%) | 51 (77.27%) | 551 (83.23%) | 853 (80.32%) |

| Adverse events | 33 (54.10%) | 9 (40.91%) | 5 (33.33%) | 46 (41.44%) | 93 (44.50%) |

| Interruption of the series due to adverse events | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Age | Mean ± SD | Minimum | Maximum | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS | 14.35 ± 2.73 | 12.00 | 25.00 | 13.00 |

| MS | 14.32 ± 3.46 | 11.00 | 21.00 | 13.50 |

| PHS | 15.07 ± 2.28 | 12.00 | 18.00 | 16.00 |

| MedS | 14.96 ± 3.39 | 9.00 | 24.00 | 14.00 |

| Total | 14.74 ± 3.16 | 9.00 | 25.00 | 14.00 |

| Variable | Vaccinated | Univariate Logistic Regression | Multivariable Logistic Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Sex | female (25.13%) | Ref. | |||

| male (12.13%) | 2.410 (0.651–8.925) | 0.187 | |||

| Place of residence | village (19.41%) | Ref. | |||

| others (22.36%) | 1.058 (0.883–1.266) | 0.540 | |||

| Place of work | only learning (21.02%) | Ref. | |||

| working (26.28%) | 1.130 (0.980–1.310) | 0.100 | |||

| Years of professional experience | not working (21.02%) | Ref. | |||

| having experience (25.76%) | 1.258 (0.883–1.792) | 0.204 | |||

| Maternal medical education | no + I don’t know (20.98%) | Ref. | |||

| yes (24.08%) | 1.240 (0.890–1.720) | 0.201 | |||

| Paternal medical education | no + I don’t know (20.71%) | Ref. | |||

| yes (31.31%) | 1.959 (1.715–2.237) | 0.001 | 1.887 (1.235–2.882) | 0.003 | |

| Partnership status | yes (21.92%) | Ref. | |||

| no (21.43%) | 1.030 (0.780–1.360) | 0.836 | |||

| Prior sexual experience | yes (20.32%) | Ref. | |||

| no (26.21%) | 0.721 (0.517–1.004) | 0.050 | 0.700 (0.500–0.978) | 0.037 | |

| Having children | no (21.10%) | Ref. | |||

| yes (34.78%) | 1.999 (1.186–3.367) | 0.009 | 1.337 (0.652–2.740) | 0.428 | |

| Marital status | single (20.92%) | Ref. | |||

| married (40.48%) | 2.577 (1.364–4.854) | 0.003 | 2.227 (1.085–4.572) | 0.029 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kałucka, S.; Śmigielski, J.; Głowacka, A.; Oczoś, P.; Grzegorczyk-Karolak, I. Retrospective Analysis of HPV Vaccination Attitudes and Uptake Among Medical Students: Implications for Preventive Healthcare. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121188

Kałucka S, Śmigielski J, Głowacka A, Oczoś P, Grzegorczyk-Karolak I. Retrospective Analysis of HPV Vaccination Attitudes and Uptake Among Medical Students: Implications for Preventive Healthcare. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121188

Chicago/Turabian StyleKałucka, Sylwia, Janusz Śmigielski, Agnieszka Głowacka, Paulina Oczoś, and Izabela Grzegorczyk-Karolak. 2025. "Retrospective Analysis of HPV Vaccination Attitudes and Uptake Among Medical Students: Implications for Preventive Healthcare" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121188

APA StyleKałucka, S., Śmigielski, J., Głowacka, A., Oczoś, P., & Grzegorczyk-Karolak, I. (2025). Retrospective Analysis of HPV Vaccination Attitudes and Uptake Among Medical Students: Implications for Preventive Healthcare. Vaccines, 13(12), 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121188