1. Introduction

The commencement of the global lockdown in 2020, which was enforced due to the COVID-19 pandemic, has given a rise to the emergence effective solutions to combat SARS-CoV-2 [

1]. Despite the fact that a lot of things still remain unknown when it comes to the methods by which the SARS-CoV-2 may develop in the long term, the scientific community agrees that the invention of an effective vaccine, and utilizing it globally, could be the best solution to put an end to the COVID-19 pandemic [

2]. Ref. [

3] proposes that numerous organizations, laboratories, and institutes across the world are researching and developing a vaccine that can provide immunity to protect those who are at risk from infection. According to the New York Times [

3], the world total number of vaccines on which researchers are working is 165; approximately 135 coronavirus vaccines are in the preclinical stage (created in laboratories but not yet tested in human trials), 21 have entered Phase I (to be tested for safety and dosage in human trials), 13 have entered Phase II (to be tested in a larger number of human trials), 8 have entered Phase III (to be tested in a larger number of human trials), and yet just 2 are approved for use on immunocompromised individuals. According to the author Turak [

4], a family travelling from Wuhan to the UAE on January 16, 2020 were found to be infected with the virus. Consequently, the government took required measures to contain the spread of coronavirus, with a response rate that was faster compared to other countries. All events were canceled, and entertainment venues were shut down. Visa services were suspended for all foreigners starting from 17 March 2020 [

5]. According to the National Emergency Crisis and Disasters Management Authority, the total number of individuals diagnosed with COVID-19 in the UAE from the beginning of the pandemic until 21 October 2022 is 1,034,462, with 2348 deaths registered due to this infection [

6].

Clearly, the spread of COVID-19 put a lot of pressure on pharmaceutical companies to develop vaccines to contain the spread of this deadly virus. Thus, scientists from all around the world developed vaccines after multiple trials and a lot of hard work. Although there are various vaccines available globally, this study will only focus on those that have been approved by the Ministry of Health in the UAE: Sinopharm, Sputnik V, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca [

7]. The first vaccine is Sinopharm, developed by a Chinese company belonging to the China National Pharmaceutical Group. The Sinopharm/BBIBP-CorV vaccine received approval in December 2020 for general public trials, and according to those trials, it showed a success rate of 79% against SARS-CoV-2 infection [

8]. Phase III clinical trials of the BBIBP-CorV vaccine consisted of 45,000 volunteers, and took place in June 2020 in seven countries: Argentina, Peru, Jordan, Bahrain, Egypt, Morocco, and the UAE [

9]. A total of 31,000 volunteers participated in the Phase III clinical trials across all the UAE, with only 15,000 individuals from the emirate of Abu Dhabi [

10]. Preliminary results of this trial encompassing the UAE and Bahrain, with a total number of 40,411 volunteers who received inactivated forms of the vaccines from two dissimilar viral strains (i.e., WIV04 and BBIBP-CorV), revealed an efficacy rate of 72.8% (for WIV04) and 78.1% (for BBIBP-CorV) in preventing symptomatic cases [

10]. Additionally, it was reported that these vaccines offered 99% rate of seroconversion, and 100% protection against severe COVID-19 infection [

10]. A very recent retrospective cohort study conducted in the emirate of Abu Dhabi in the UAE revealed that the efficacy of the Sinopharm vaccine against hospitalization is 79.6% (95% CI, 77.7 to 81.3), whereas the efficacy against critical care unit admission was found to be 86% (95% CI, 82.2 to 89.0), with only 84.1% (95% CI, 70.8 to 91.3) effectiveness rate against death due to SARS-CoV-2 infection [

11]. Moreover, the study results pointed out that the efficacy of this vaccine against severe COVID-19 outcomes has declined over the time, which highlights the importance of administering booster doses to improve the vaccine’s protective capacity [

11].

The second vaccine is Pfizer, an RNA-based vaccine that was developed by the German company BioNTech, which was originally an American pharmaceutical company [

12].

The BNT162b2 and BNT162b1 vaccines are mRNA-based vaccines. They are formulated via the injection of a synthetic mRNA into a protein, and then translated rapidly by the host cell [

13]. Treatment using mRNA technology is considered well-tolerated and safe due to the rapid metabolism and the transient expression of the RNA, as well as the avoidance of integration into the host genome [

14]. Recently, it has been found that modifying mRNA molecules with 1-methylpseudouridine has given a rise to a long-term antibody response, whereas encompassing the mRNA with liquid nanoparticles offered protection against degradation [

15]. Back in December 2020, BNT162b2 received authorization for emergency use, temporarily, in the UK, based on data submitted from Phase III clinical trials; consequently, a series of authorization approvals for emergency use took place in other countries, including Mexico, Canada, USA, Bahrain, and Saudi Arabia [

16]. BNT162b2 requires storage in a temperature range of −80 °C to −60 °C, and it must be thawed, then diluted, prior to use [

17], which represents a challenge for vaccine distribution [

18]. The efficacy rate of BNT162b2 was reported as 95.0% effective (95% CI 90.3–97.6) in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients without a prior history of contracting COVID-19, up to 7 days after receiving the second dose of the vaccine in Phase II/III clinical trials [

19]. Additionally, in global Phase I/II/III placebo-controlled clinical trials (NCT04368728), only 8 cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection were reported, with an onset of more than or equal to 7 days after the second dose in the BNT162b2 recipients group, whereas 162 cases of COVID-19 infection took place in placebo recipients [

19]. Mousa et al. [

20] conducted a study in the UAE to evaluate the efficacy of mRNA BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) and BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm) against the new variant of COVID-19, the Delta variant (B.1.617.2), among fully vaccinated individuals. Their results demonstrated that Sinopharm vaccine efficacy in preventing critical care hospital admissions was 95% (95% CI: 94, 97%)], while the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine had an efficacy rate of 98% (95% CI: 86, 99%) [

20].

The third vaccine is Sputnik V, a Russian vaccine produced by the Gamaleya National Center of Epidemiology and Microbiology medical research institute in Russia [

21]. It is composed of a two-part adenovirus viral vector, which aims to provoke the production of antibodies that counteracts spike proteins [

21]. The launch of the Sputnik V vaccine was rather controversial among the scientific community, especially due to the fact that Russia announced their vaccine and approved it in August 2020 prior to gathering detailed clinical data [

22]. Moreover, the efficacy rate of 92% claimed upon releasing the initial results was criticized since it was based on a very low number of participants [

22]. However, in February 2021, the results of Phase III randomized, placebo-controlled, double blind clinical trials involving 22,000 adults aged 18 years and above were published [

23]. Participants in this study either received a placebo or two doses of the vaccine, with a spacing duration of 21 days, and the overall efficacy reported in this paper was 90% among 14,964 vaccinated individuals, and no serious side effects were reported, as most of the adverse events were mild, although over 50% of vaccine recipients experienced pain at injection site [

23].

The fourth vaccine is AstraZeneca, which was developed by Oxford University, England, and sold under the names Covishield and Vaxzevria [

24]. More than 20 million people were vaccinated in the UK with this vaccine, among which, 79 cases of blood clots and 19 deaths were reported [

25]. These numbers equate to around one case of a blood clotting adverse event per 250,000 people vaccinated with the AstraZeneca vaccine, with an incidence rate of 0.0004% and one death in a million [

26]. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) reported that “benefits of vaccination outweigh any risks of side effects”, because COVID-19 infection also poses a dangerous risk of developing fatal blood clots, including deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism [

27]. Moreover, the EMA stated that there was no ultimate link found between the vaccine and the direct cause of blood clots, and this should rather be described as a rare immune response towards the vaccine [

26]. On March 2022, the company announced that the initial analysis of AstraZeneca vaccine efficacy revealed 79% efficacy rate in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection in a multinational clinical trial that included 32,449 adults from Peru, Chile, and the US [

28]. It is also noteworthy that there was no hospitalization or death cases among the participants who received two doses of the vaccine, despite the fact that 60% of them had comorbidities that are linked to increased risk of developing severe symptoms such as obesity or diabetes [

28].

Despite the high rate of morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19, many individuals rejected the vaccination for various reasons. A randomized, cross-sectional study conducted in Jordan, implementing a machine learning approach for predicting the severity of side effects of COVID-19, found that about 45% of individuals feared the side effects, 29% did not trust vaccines at all, and 20% did not even know how vaccines worked [

29]. By refusing to vaccinate, individuals are not only harming themselves but the people around them. Since discussing what to expect post vaccination will aid in lowering the community’s trepidation and hesitancy towards the different types of vaccines available, we sought to perform this study to demonstrate the possible short-term adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccines, as well as their short-term efficacy, in order to maximize the trust in the vaccination process and speed up the process of gaining herd immunity.

4. Discussion

Shengli Xia et al. [

33] proposed one of the first pieces of evidence that came out earlier in August 2020 confirming the efficacy of the BBIBP-CorV vaccine was obtained via the short-term analysis of two randomized clinical, which revealed that the Sinopharm vaccine is capable of stimulating immunogenicity with low incidences of adverse events. However, Phase III trials are required to further elaborate the vaccine’s efficacy in the long term. Based on the interim data concerning the Phase III clinical trials of the Sinopharm vaccine in Egypt, Jordan, Bahrain, and Peru, the vaccine’s efficacy was found to be 72.5% [

34], which is lower than the 86% efficacy rate reported by the UAE in December 2020 [

35]. Another country in which the vaccine has been trialed recently, in January 2021, is Brazil, and in a Brazilian study involving 12,000 health workers, it was found that the BBIBP-CorV vaccine is 78% effective at preventing mild cases of COVID-19 [

36]. Moreover, a study conducted earlier in April 2021 by the University of Chile reported that the efficacy of two shots of the SinoVac after 2 weeks in Phase III trials had dropped to 56.5% [

37]. However, the Sinopharm company have recently collaborated with the UAE to experiment an extra third dose, hoping to further increase the antibody response and enhance the efficacy [

38]. Interestingly, a very recent observational study conducted in Bahrain involving a family that became reinfected despite receiving the vaccination concluded that the Sinopharm vaccine is able to offer protection and reduce casualty [

39]. However, it cannot prevent the recurrence of the infection, and this finding seems to be due to a mutation in the S protein of the virus, referred to as E484K. Nevertheless, in the same study, two individuals who took different types of the vaccination, and had direct contact with an infected family member, did not show any symptoms. As a result, the Bahraini government started administering the Pfizer booster to Sinopharm vaccine recipients [

39].

The findings of our study show that 94.4% of Sinopharm vaccine recipients have not been reinfected with COVID-19 after receiving two shots, taking into consideration that the majority of participants (n = 56,487.03%) received the vaccine doses in a period of time within January to February 2020. Moreover, 34 out of 36 participants who received the Sinopharm vaccine stated that they required no hospitalization upon contracting COVID-19 infection post vaccination, thereby suggesting that the vaccine can prevent hospitalization rates by 94.4%.

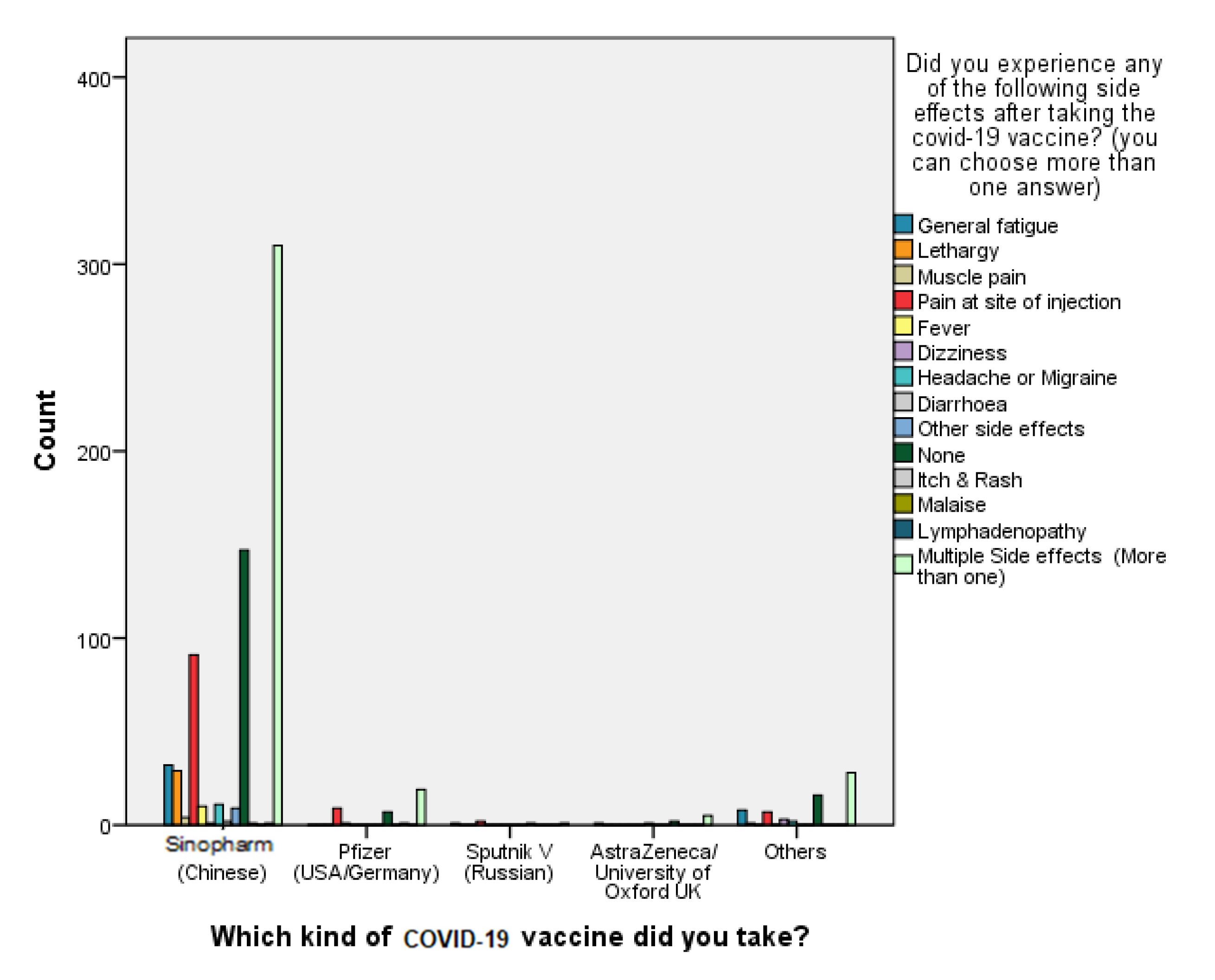

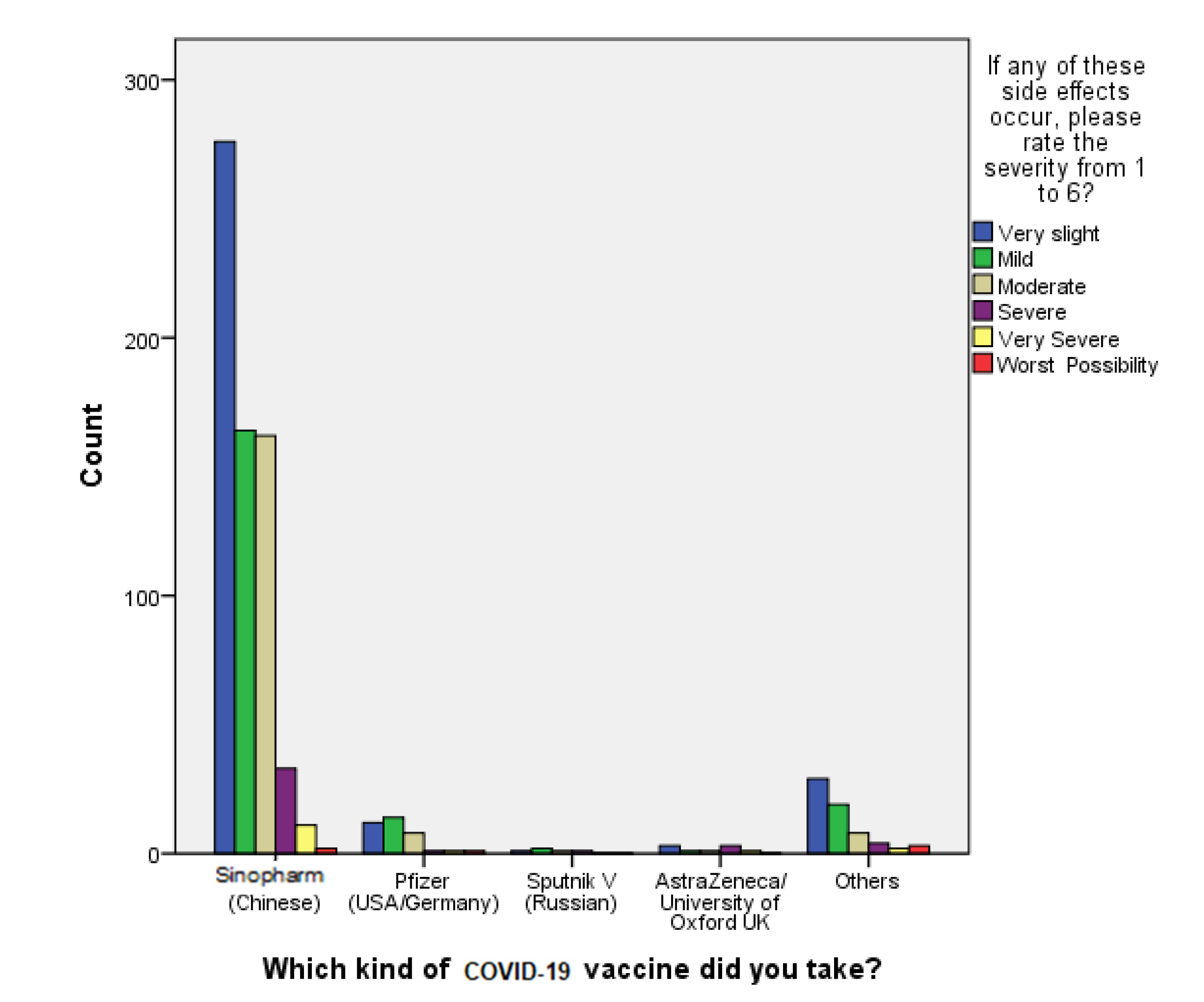

When it comes to the safety of the Sinopharm vaccine, B. Q. Saeed et al. [

31] conducted a study earlier in April 2021 concerning self-reported side effects of SinoVac inside the UAE, and it was concluded that the first- and second-dose post-vaccination side effects were mild and predictable, and there were no hospitalization cases [

31]. These data are in agreement with our study findings, which reveal that 92.9% of the participants reported very slight to moderately severe side effects experienced post vaccination, which tackles the vaccine-related conspiracy theories that claim the unsafety of the vaccine. On the other hand, the first piece of evidence obtained that confirmed the efficacy of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine was acquired from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 43 thousand volunteers, who had a median age of 52 years old. The results revealed that the vaccine’s efficacy rate was around 95%, but it was also associated with several adverse events that took place within a few days of receiving the vaccination dose [

40]

. These adverse effects were divided into two categories, local or systemic side effects, and their severity ranged from mild to moderate [

41]. According to the FDA report concerning the local side effects of Pfizer-BioNTech upon receiving the first dose and the second dose of the vaccine, it was found that the frequency of local side effects is slightly higher after the second dose in comparison with the first dose, and this trend was more significant in the case of systemic side effects [

40]. Our study data confirm this trend only in the reported local side effect “pain at site of injection”, which was more frequent following the second dose of the vaccine, whereas the systemic side effect “lethargy” was more prominent following the first dose compared to the second dose.

According to Gushchin et al. [

42] concerning the short-term efficacy of Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine, those who had been vaccinated had no cases of moderate or severe COVID-19 infection after receiving the first dose of the vaccine for at least 21 days. Interestingly, our study findings reveal that only one out of the five recipients of the Sputnik V vaccine became reinfected with COVID-19 within 2–7 days of vaccination despite receiving the second dose. However, this participant revealed that the COVID-19 infection severity was very slight post vaccination. The majority of our study participants (

n = 710 or 92.9%) stated that they did not become reinfected after receiving two doses of COVID-19 vaccine; therefore, the mean score of the Likert scale question regarding severity of the infection symptoms after vaccination was found to be 1.16 with a mean standard deviation of 0.660, which leans towards the answer “not been infected”.

Since the incidence of post-vaccination COVID-19 infections was significantly low, the incidence of being hospitalized after vaccination was negligible (

p < 0.001). This was further confirmed by the fact that most individuals who became reinfected (

n = 49 or 90.7%) stated that they did not require hospitalization during their reinfection period after the vaccine. However, it is noteworthy that about one-third of individuals reinfected with COVID-19 after vaccination (

n = 18 or 33.33%) declared that they have caught the infection within a period of time that varied from 2–4 weeks from vaccination. In addition, when a Kruskal–Wallis H test was conducted, it showed a statistically significant difference in the severity of COVID-19 infection post vaccination between the different types of vaccination (chi-square: χ2(2) = 19.323, df= 4,

p = 0.001), with a mean rank severity score of 376.63 for Sinopharm (Chinese), 427.38 for Pfizer (USA/Germany), 428.40 for Sputnik V (Russian), 355.50 for AstraZeneca/ University of Oxford, UK, and 415.73 for others. Out of the 764 participants involved in our study, consisting of 519 who do not consume any addictive substances and 245 smokers and those who consumed addictive substances such as caffeine and cigarettes, 93.1% of the non-smokers group (

n = 483) experienced very slight to moderate symptoms of COVID-19 vaccines, whereas only 36 out of 519 reported severe symptoms. On the other hand, concerning the smokers group, 218 out of 245 had very slight to moderate symptoms post vaccination vs. 27 who reported severe symptoms. The odds ratio of developing severe vaccine symptoms in non-smokers vs. smokers was 1.662 (95% CI, 1.046 to 0.629). Additionally, a Mann–Whitney U test was ran to determine whether there were differences in the rating of the severity of COVID-19 symptoms in the case of recurrent infection post vaccination between smokers or consumers of addictive substances and non-smokers. Distributions of the engagement scores for both groups were similar, as assessed by visual inspection. The median engagement score was not statistically significantly different between the two groups, U = 61,807.5, z = −1.399,

p = 0.162. Thus, our results reveal that the smoking status of cigarettes or consuming other addictive substances was found not to be related to the COVID-19 vaccination efficacy, as the reported (two-tailed)

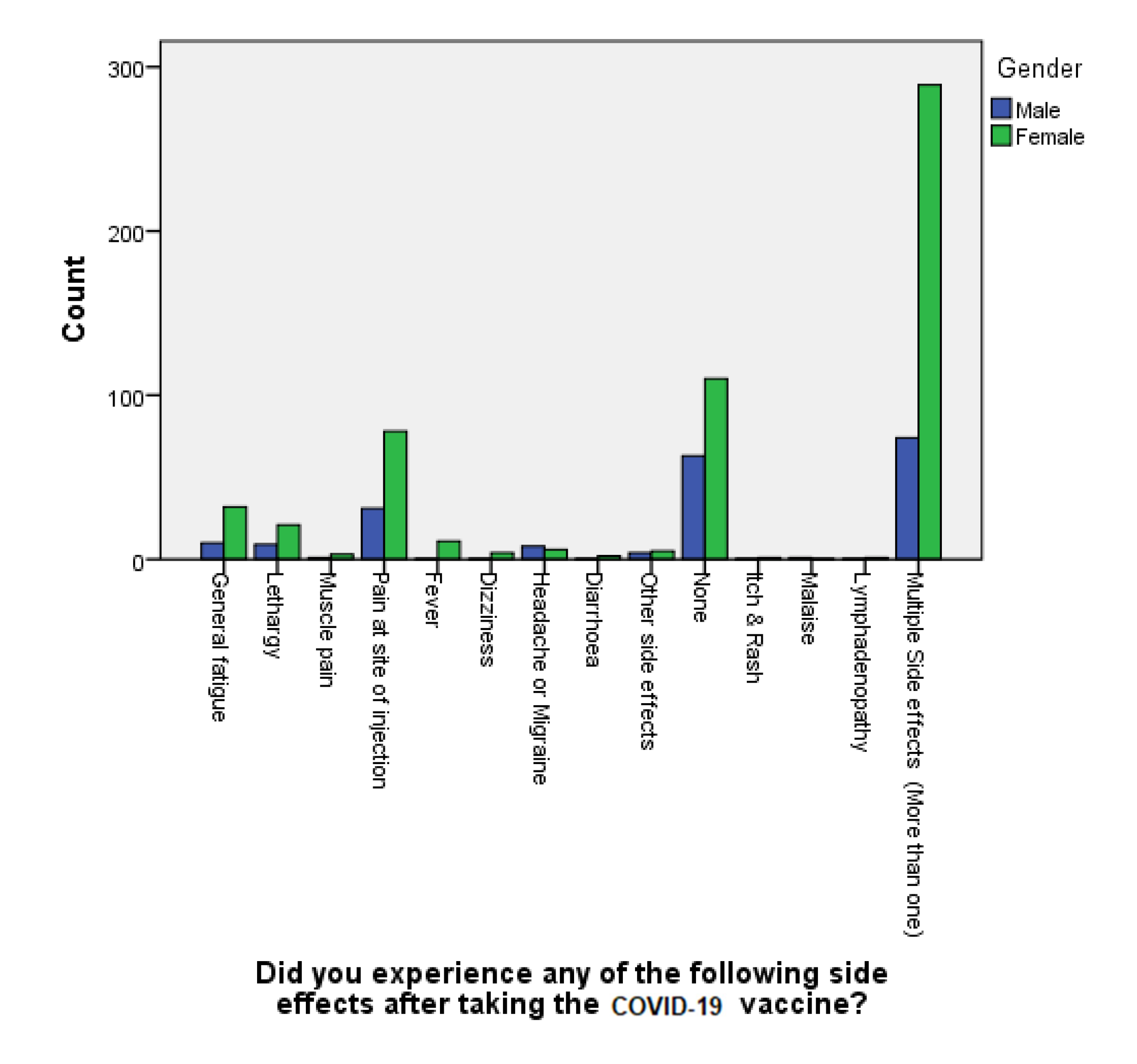

p-value was 0.162, which is not statistically significant. Using a chi-square test, out of all the respondents, our study reveals that females, especially younger individuals, belonging to the age group between 18–24 years old, were found to be more susceptible to the adversities of COVID-19 vaccination (chi-square: χ2(2) = 1824.174 df= 12,

p < 0.001). This finding is in agreement with other studies in the literature that considered belonging to the female gender a significant risk factor for experiencing vaccination side effects, with a

p-value of 0.0028 [

43,

44]. Al-Qazaz et al. attributed this increased incidence of multiple side effects post COVID-19 vaccination among females in particular to psychological and hormonal factors [

45]. Another proposed explanation for this phenomena is the variability in the level of endogenous opioids and sex hormones between the two genders, which could lead to differences in the pain threshold and the extent of coping with stressors, according to Bartley et al. [

46]. Lastly, numerous studies aiming to explain the probable reasons behind gender-related disparities in experiencing adverse events after COVID-19 vaccinations have reported that the female estradiol hormone tends to trigger the formation of more antibodies, which leads to more prominent immunological responses compared to men, whereas their testosterone sex hormone would act in an opposite manner, and result in the increased likelihood of contracting a viral infection due to the lowering the immune response [

47,

48,

49].