Abstract

The outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has caused a lot of disruptions around the world. In an attempt to control the spread of the disease among the population, several measures such as lockdown, and mask mandates, amongst others, were implemented by many governments in their countries. To understand the effectiveness of these measures in controlling the disease, several mathematical models have been proposed in the literature. In this paper, we study a mathematical model of the coronavirus disease with lockdown by employing the Caputo fractional-order derivative. We establish the existence and uniqueness of the solution to the model. We also study the local and global stability of the disease-free equilibrium and endemic equilibrium solutions. By using the residual power series method, we obtain a fractional power series approximation of the analytic solution. Finally, to show the accuracy of the theoretical results, we provide some numerical and graphical results.

1. Introduction and Preliminaries

The study of mathematical models of infectious diseases has attracted the attention of many researchers since they provide a better understanding of their evaluations, existence, stability, and control [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Most of the mathematical models of infectious diseases are composed of a system of integer-order differential equations. However, in the last few decades, fractional-order differential equation has been used in the modeling of biological phenomena because they provide a greater degree of accuracy than the integer-order models [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. The theory of fractional calculus, which involves differentiation and integration of non-integer orders, is as old as the classical calculus of integer orders. However, this theory has gained considerable attention from many researchers in recent years due to the numerous applications found in the sciences, engineering, economics, control theory, and finance, amongst others. The increasing interest in using fractional calculus in the modeling of real-world phenomena is due to its various properties which are not found in classical calculus. Unlike the integer-order derivatives, which are local in nature, most of the fractional-order derivatives (for example, the Caputo and Riemman–Liouville fractional order derivatives [14,15]) are non-local and possess the memory effects which make it more superior because in many situations the future state of the model depends not only upon the current state but also on the previous history. For this realistic property, the usage of fractional-order systems is becoming popular to model the behavior of real systems in various fields of science and engineering. Many researchers have therefore expanded the integer-order models to fractional-order models via various mathematical techniques. Recently, several authors have used fractional-order models to understand the dynamics of the COVID-19 epidemic to achieve the best strategies to stop the spread of the disease, chose a better effective immunization program, allocate scarce resources to control or prevent infections and also predict the future course of the outbreak [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

Motivated by the above works and the high interest in finding the best solution to control the COVID-19 pandemic, we study a fractional-order model to understand the dynamics of the COVID-19 infections when the population is under lockdown. Most of the COVID-19 models in the literature, to the best of our knowledge, do not include the impact of the preventive measures adopted by many governments around the world to control the virus. Lockdown was one of the preventive measures and that makes our model quite unique and interesting.

Several definitions of fractional derivatives and integrals have been provided in the literature. For the purpose of this work, we present the definitions and some properties of the Riemann–Liouville fractional integral, Caputo fractional derivative and other related fractional-order derivatives. For more information about the Riemann–Liouville fractional integral and the Caputo derivative, we refer the interested reader to [14,15] and the references therein.

Definition 1

([14]). The Riemann–Liouville fractional integral of order of a function f is given by

where Γ denotes the Gamma function defined by

Definition 2

([14]). The Caputo fractional derivative of order is given by

The Caputo derivative satisfies the following properties:

- 1.

- .

- 2.

- 3.

- .

- 4.

- .

- 5.

- , for .

- 6.

- , for .

Most fractional-order differential equations do not have a closed-form solution, and thus approximation and numerical methods are extensively used. One way to find an approximated solution of a system of fractional-order differential equations is by using the technique of fractional power series. The following is the definition of the fractional power series.

Definition 3

([28]). The fractional power series about is defined as

where for some and for are the coefficients of the power series.

The following result hold for the Caputo derivative.

Theorem 1

([28]). Suppose the fractional power series representation of f is of the form

If for are continuous on the interval , then , where (m-times) and ρ is the radius of convergence.

Remark 1.

We note that the kernel function in the definition of the Caputo derivative has a singularity at . Recently, some new fractional derivatives with non singular kernels were introduced in the literature and we present them here for the readers’ reference.

In 2015, Caputo annd Frabrizio [29] proposed the following generalization of the Caputo derivative as follows:

Definition 4.

The Caputo–Fabrizio fractional-order derivative (CF) of order α is defined as follows:

where is a normalization function such that . The Caputo–Fractional derivative of a constant function is zero, but unlike the Caputo derivative in (2), the kernel does not have a singularity at .

The Caputo–Fabrizio fractional-order had also been generalized by Atangana and Baleanu in 2016 as follows:

Definition 5

([30]). Let and . The Atangana–Baleanu fractional-order derivative in the Caputo sense is given by

where is a normalization function such that , is the one parameter Mittag–Leffler function (see Remark 3) and is the Sobolev space of order one defined as follows:

We refer the interested reader to [29,30] and the references therein for more information about these fractional derivatives.

Remark 2.

It is worth pointing out that recently, Hattaf [31] also introduced some new generalizations of the Attangana–Baleanu fractional-order derivatives by introducing a weight function and thus giving rise to the definition of several fractional-order derivatives with non-singular kernels.

Next, we present the definition of the two-parameter Mittag-Leffler function, which will be utilized later in the paper.

Definition 6

([28,32]). The two-parameter Mittag-Leffler function denoted by , is defined as

Remark 3.

When in (6), then we have the one parameter Mittag-Leffler function which is denoted by . That is,

2. Model Formulation

In order to understand the impact of lockdown in preventing the spread of COVID-19 infection, Baba et al. [33] proposed the following model governed by a system of nonlinear ordinary differential equations:

subjected to the initial conditions

In this model, the authors considered a population of total size at time t with a constant recruitment rate of . The population is divided into four compartments denoted by and . The class denotes the susceptible individuals that are not under lockdown. The group contains those individuals who are susceptible and are under lockdown. The group who are infected and are not under lockdown are represented by , while those individuals who are infected and are under lockdown are denoted by Finally, the cumulative density of the lockdown program is denoted by The authors have studied the local stability of the equilibrium solutions in relation to the basic reproduction number.

In order to include the memory effects and the past history to get a better understanding of the dynamics of COVID-19 infections under lockdown, we reformulate the model (7) by using the Caputo fractional derivative as follows:

where denotes the Caputo derivative for ; under the initial conditions

We explore some interesting results of the fractional-order COVID-19 model (8), description of the parameters shown in Table 1. In particular, after proving the existence of a unique positive global solution of the model, we study the local and global stability of the various equilibrium points of the fractional-order model using the comparison theory of fractional differential inequality and fractional La-Salle invariance principle. Moreover, we apply the method of residual power series technique to approximate the solution of the fractional-order system (8). Finally, we provide numerical simulations to illustrate some of the theoretical results and error analysis to show how good the approximated solution is.

Table 1.

Description of the parameters used in the COVID-19 epidemic model (8).

Remark 4.

In [17], the authors also discussed a slightly different extension of the model in (7) to fractional calculus where they include the order of the fractional derivative as powers on the parameters. They established the existence and uniqueness of solutions to their model using the Schauder and Banach fixed point theorems.

Denote the set as follows,

Theorem 2.

Proof.

Clearly, and are continuous for all Moreover,

where and are two positive constants. Thus by Theorem (3.1) and remark (3.2) of [34], the system (8) has a unique solution.

Now, to prove that is positively invariant, let . Then adding the first four equations of system (8), we have

Taking the Laplace transform on both sides yields

Simplifying this equation, we have the following inequality

Taking the inverse Laplace transform and using the fact that

where is the Mittag-Leffler function defined in (6), we have

Consequently, inequality (9) and the last equation of system (8), implies that Similar to the above discussion, taking the Laplace transform and using the Mittag-Leffler function, it follows that for any .

In conclusion, for any we have and for any and thus is positively invariant. □

3. Equilibrium Points and Basic Reproduction Number

One way to see what will happen to the population eventually is to explore when the system is at equilibrium. By setting

we get the following equilibrium points

and

where

and , where is the solution of the equation , where

The disease-free equilibrium is the case when the pathogen has suffered extinction and, in the long run, everyone in the population is susceptible. The endemic equilibrium is the state where the disease cannot be totally eradicated and remains in the population without a lockdown, while is the endemic equilibrium point in the presence of lockdown. The basic reproduction number of the model, denoted by , is a constant that is used to approximate the expected number of cases directly generated by one case in a population where all individuals are susceptible to infection. One way to calculate is using the next generation matrix approach [35]. The rate at which secondary infections are produced is given by

where and for

Similarly, the transfer of infection from compartment i to j is given by

where and for

Now define the next generation matrix G as

Hence is the dominant eigenvalue of G and it is given by

4. Local and Global Asymptotic Stability of the Disease-Free and Endemic Equilibrium Points

We use the following theorem to prove the local asymptotic stability of the disease-free equilibrium point

Theorem 3

([36]). Given a fractional-order system of differential equation

Let be an equilibrium point of the given system, and let be the Jacobian matrix of f evaluated at . Then is locally asymptotically stable if and only if , for all eigenvalues of the matrix A.

Theorem 4.

The disease-free equilibrium point is locally asymptotically stable if

Proof.

After calculating the associated Jacobian matrix of system (8), it can be shown that the characteristic equation of the Jacobian matrix satisfies

Note that iff As a result, all the eigenvalues are negative real numbers, and hence for any Thus by Theorem 3 the disease-free equilibrium point is locally asymptotically stable. □

Definition 7

([32,37]). An equilibrium point of system (8) is Mittag-Leffler stable if

where is any norm on and , where is locally Lipschitz on Ω with Lipschitz constant , and is a one-parameter Mittag-Leffler function which can be defined in terms of the two-parameter Mittag-Leffler function as .

Remark 5.

Since Mittage-Leffler stability implies global asymptotic stability (see Remark 4.4 in [38]), it is sufficient to prove the disease-free equilibrium point is Mittage-Leffler stable on

Note that a similar result is provided in Definition 5 [39] for a generalized Hattaf fractional (GHF) derivative which encloses the popular forms fractional derivatives with non-singular kernels.

Theorem 5.

If , then the disease-free equilibrium point is Mittage-Leffler stable on

Proof.

Define the positive definite Lyapunov function

where and are two positive constants that will be determined later in the proof. By linearity of the Caputo fractional derivative, we have

If then we can choose such that

Now taking the Laplace transform of inequality (17) results

Thus using (2), we have

Remark 6.

The proof of the local stability of the endemic equilibrium point is similar to Theorem 4. Thus we will provide proof of the global stability of by constructing a Lyapunov function.

Theorem 6

([40]). Let be an equilibrium point for the non-autonomous fractional-order system . Also let be a continuously differentiable function such that

and

for all and all , where are continuous positive definite functions on Then the equilibrium point is globally asymptotically stable.

Now using Theorem 6 we will show that the endemic equilibrium point of system (8) is globally asymptotically stable under some conditions.

Theorem 7.

If , then is globally asymptotically stable in Ω.

Proof.

Consider the Lyapunov function

where

and k is a positive constant to be determined later in the proof. Using Lemma 3.1 and Remark 3.1 of [41] we have

and by the linearity property of the fractional Caputo derivative, it follows that

Choose any and note that if then Thus if then and also if and only if , and Therefore the largest compact invariant set in

is the singleton set containing the endemic equilibrium Thus by Theorem 6, we conclude that the endemic equilibrium is globally asymptotically stable in . □

Since the proof of the local stability of the endemic equilibrium point with lockdown is similar to the proof of (4), we will provide the proof of the global stability of the endemic equilibrium point with lockdown

Theorem 8.

If , then the endemic equilibrium point with lockdown, , is globally asymptotically stable in Ω.

Proof.

We start by defining a Lyapunov function

where is the endemic equilibrium point with lockdown given in Equation (11). Note that and using Lemma 3.1 and Remark 3.1 of [41] we have the following

Using Equation (11) we have the following inequality

Let Then it follows that

Thus it follows that . Similarly, it can be shown that if

, then since

and the fact that . Thus under the given assumption that it can be concluded that and if and only if . This result, together with the last two equations of (8), will imply that and As a result, the endemic equilibrium point is globally asymptotically stable. □

5. Approximate Solution

In this section, we present a solution of the fractional-order model by using the residual power series method, which consists of expressing the solution as fractional power series expanded about the initial point .

Consider the following fractional-order model:

where denotes the Caputo derivative for with and ; under the initial conditions

Similar to the procedure in [42], we do the following steps in order to obtain a fractional power series solution for the nonlinear fractional-order model in (26).

Step 1: Suppose that the fractional power series of and around are as follows:

where for some . Now, we let and denote the n-th truncated power series approximation of and , respectively. That is,

Step 2: Next, we define the residual functions for the model in (26) as follows:

Hence, the n-th residual functions for and , respectively, are as follows:

Now, we observe that

, and

Since the Caputo derivative of any constant is zero, it is straightforward to see that for

Step 3: To obtain the coefficients and , for , we substitute the n-th truncated series of and into (30) and then apply the Caputo fractional derivative operator on and , and evaluate the result at . We obtain the following algebraic system of equations.

for .

Step 4: We solve the algebraic system (31) for the values of for to get the n-th residual power series approximate solution of the system in (26).

Step 5: We repeat the procedure to obtain a sufficient number of coefficients. Higher accuracy for the solution can be achieved by evaluating more terms in the series solution.

By following the steps outlined in above, we derive a recursive formula for the coefficients as follows:

First, we note that the coefficients and are given by the initial conditions. That is,

The first truncated power series approximations will have the forms:

Thus, the first residual functions are:

Evaluating and at , we have

By solving the equations

we have that

Now, the second truncated power series approximations will have the forms:

So, the second residual functions are:

We apply the operator to and and then evaluate the result at to get

By solving the equations

we have

Similarly, the third truncated power series approximations are given by

So, the third residual functions are:

We apply the operator to and and then evaluate the result at to get

By solving the equations

we have

By continuing in this direction, we deduce that the coefficients and for are given by the recursive formula

Remark 7.

It is worth noting that these recursive formulas for the coefficients will ensure that we obtain higher-order approximate solutions as compared with similar results in the literature with a smaller order of the approximate solutions. Thus, due to this recursive nature of the coefficients, we can calculate and for any large n values if necessary. For the purpose of the numerical simulation given in Section 6, we used . That is, the coefficients for are computed and the approximated fractional power series solutions of system (8) are plotted in Section 6, numerical simulation and examples.

6. Numerical Simulations and Examples

The following table provides the description of the different parameters used in the COVID-19 model. The parameter values under column “data set 1” yield a basic reproduction number . Similarly, if the parameters under the column “data set 2” are used, then we have . In Section 6.1, we simulate both the exact and approximated solutions of system (8) using the values under “data set 1” of Table 2 for various values ( and 1). In Section 6.2, we simulate the exact and approximated solutions of system (8) using the parameter values under “data set 2” of table Table 2. Moreover, in both cases () the relative errors, due to approximating the exact solution of system (8) by the residual power series method, are computed for different values as indicated in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Relative error of the state variables for different values of when .

Table 4.

Relative error of the state variables for different values of when .

6.1. Exact and Approximated Solutions of System (8) When

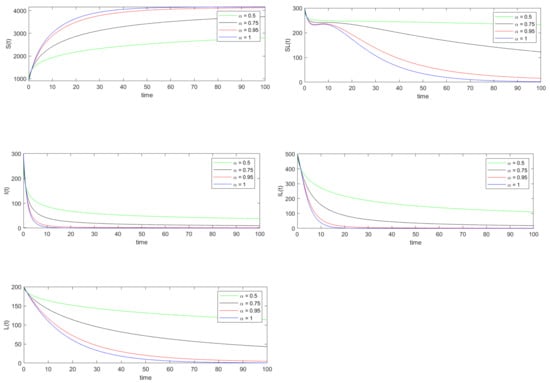

Using data set 1, the basic reproduction number is calculated to be 0.2373. Thus by Theorems 4 and 5, the disease-free equilibrium point is both locally and globally asymptotically stable. The disease-free equilibrium point is calculated to be . The simulations in Figure 1 and Figure 2 support the fact that the trajectories of system (8) converges to this equilibrium point .

Figure 1.

Numerical simulation of the trajectories of the solution of system (8) when

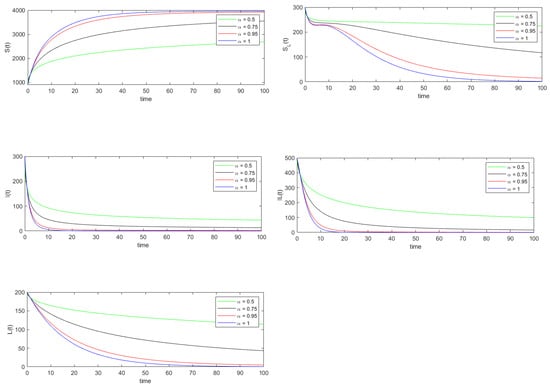

In Figure 1 and Figure 2 the exact and approximated solutions of system (8) are plotted for , respectively. In order to show the accuracy of the residual power series method for approximating the solution of system (8), we have calculated the relative error of each state variable for various values. A time step size is considered and for each state variables the values are calculated where The relative error for the state variable is computed using

where and represent the exact and approximated values of the variable at for As can be seen from Table 3, the relative error of each state variable decreases as the value of increases from 0.5 to 1.

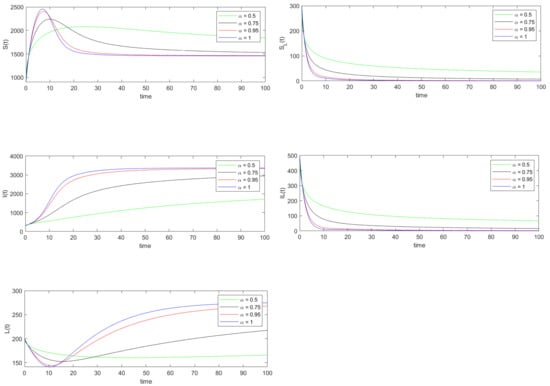

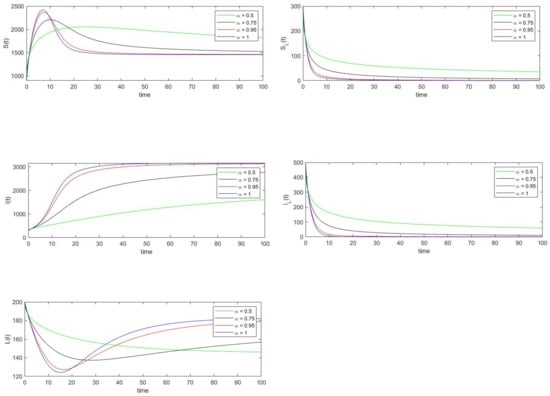

6.2. Exact and Approximated Solutions of System (8) When

The basic reproduction number is calculated using the parameter values under data set 2. The value of is found to be 4.5707, and also the condition is satisfied. Thus by Remark 6 and Theorem 7 the endemic equilibrium point , which is calculated using Equation (10), is both locally and globally asymptotically stable. Note that both Figure 3 and Figure 4 show that the trajectories of the solution of system (8) converges to the equilibrium point .

Figure 3.

Numerical simulation of the trajectories of the solution of system (8) when

Similar to the previous discussion, the relative errors of the state variables are calculated for various values using Equation (33).

7. Conclusions and Discussion

In this paper, a fractional-order COVID-19 epidemic model with lockdown is proposed and analyzed. In particular, some of the most important epidemiological constants, such as the equilibrium points ( and ) and the basic reproduction number , are calculated. The existence and uniqueness of a positive global solution of the fractional-order system (8) is established. Moreover, by implementing various techniques such as the comparison theory of fractional-order differential equations, Mittage-Leffler stability (Theorem 5), and fractional La-Salle invariance principle (Theorem 6), the local and global stabilities of the equilibrium points are discussed. Additionally, the method of residual power series is used to approximate the solution of system (8). As can be seen in Equation (32), the coefficients and have recursive nature. That is, for any , each coefficients and can be determined from the previous ones and . Thus we can calculate as many coefficients as we need in order to get a very good approximation of the solution of system (8). Moreover, it is very interesting to note that as the value of increases from 0.5 to 1, the trajectories of the solution of the fractional-order system are converging to the case where . That is, the solutions of the fractional-order differential equation converge to the solutions of the system of the ordinary differential equation as the order increases towards 1. In Section 5, numerical simulations and examples are presented to show the stability of the equilibrium points when and The exact solutions of system (8) for various values are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 3. Similarly, the approximated solutions of system (8) using the residual power series method are included in Figure 2 and Figure 4. Finally, in order to see the accuracy of the approximated solutions, we provided the relative errors for different values as shown in Table 3 and Table 4. The model that is studied in this paper can be used to predict and understand how COVID-19 infection spreads in the presence of a lockdown. In addition to understanding the dynamics of the infection, it is very important to determine the relative importance of the various parameters used in the model. One such technique is the study of the sensitivity of the parameters in relation to the basic reproduction number , and the two endemic equilibrium points and , which are considered to be the most important values in the study of deterministic epidemic models. One such approach is to calculate the normalized sensitivity index (NSI), denoted by , where is the given parameter. For example, if is one of the parameters in , then the NSI of is defined as Using this result, we have calculated the NSI of the parameters and which are directly affected by the infection. As a result, we have , and Thus in order to decrease , the expected number of infections generated by one case, we have to either decrease the infection contact rate or increase the recovery rate of the infected group This further implies imposing some prevention actions, such as avoiding contact with people who are infected, wearing masks, and keeping a distance from an infectious person, will help to decrease the value of , which directly leads to mitigating the infection. By modifying this model, one can study other aspects of the infection, such as the impact of vaccination, the effect of population diffusion, and other important factors that determine the transmission and persistence of the infection.

Author Contributions

All authors have equally contributed in terms of Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, writing the original and revised manuscript, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baleanu, D.; Kai, D.; Enrico, S. Fractional Calculus: Models and Numerical Methods; World Scientific: Singapore, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Djordjevic, J.; Silva, C.J.; Torres, D.F.M. A stochastic SICA epidemic model for HIV transmission. Appl. Math. Lett. 2018, 84, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajji, M.; Al-Mdallal, Q. Numerical simulations of a delay model for immune system-tumor interaction. Sultan Qaboos Univ. J. Sci. [SQUJS] 2018, 23, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndairou, F.; Area, I.; Nieto, J.J.; Silva, C.J.; Torres, D.F.M. Mathematical modeling of zika disease in pregnant women and newborns with microcephaly in Brazil. Math. Meth. Appl. Sci. 2018, 41, 8929–8941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachah, A.; Torres, D.F.M. Dynamics and optimal control of ebola transmission. Math. Comput. Sci. 2016, 10, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihan, F.A.; Al-Mdallal, Q.M.; AlSakaji, H.J.; Hashish, A. A fractional-order epidemic model with time-delay and nonlinear incidence rate. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2019, 126, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Korkmaz, A.; Rafiq, M.; Baleanu, D.; Alshomrani, A.S.; Rehman, M.A.; Iqbal, S. A novel time efficient structure-preserving splitting method for the solution of two-dimensional reaction-diffusion systems. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafa, A.A.M.; Rida, S.Z.; Khalil, M. Solutions of fractional-order model of childhood diseases with constant vaccination strategy. Math. Sci. Lett. 2012, 1, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baleanu, D.; Mohammadi, H.; Rezapour, S. A mathematical theoretical study of a particular system of caputo fabrizio fractional differential equations for the rubella disease model. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, F.; Shah, K.; Rahman, G.; Shahzad, M. Numerical analysis of fractional order model of HIV-1 infection of CD4+ t-cells. Comput. Method Differ. Equ. 2017, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.; Singh, J.; Rathore, S. Application of homotopy analysis transform method to fractional biological population model. Rom. Rep. Phys. 2012, 65, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lia, Y.; Haq, F.; Shah, K.; Shahzad, M.; Rahman, G. Numerical analysis of fractional order pine wilt disease model with bilinear incident rate. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2017, 17, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magin, R. Fractional Calculus in Bioengineering; Begell House Publishers: Redding, CT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Samko, S.G.; Kilbas, A.A.; Marichev, O.I. Fractional Integrals and Derivatives; Gordon and Breach Science Publishers: Yverdon-les-Bains, Switzerland, 1993; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Aba Oud, M.A.A.; Ali, A.; Alrabaiah, H.; Ullah, S.; Khan, M.A. A fractional order mathematical model for COVID-19 dynamics with quarantine, isolation, and environmental viral load. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2021, 2021, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Baba, I.A.; Yusuf, A.; Kumam, P.; Kumam, W. Analysis of Caputo fractional-order model for COVID-19 with lockdown. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, M.S.; Shah, K.; Wahash, H.A.; Panchal, S.K. On a comprehensive model of thenovel coronavirus (COVID-19) under mittag-leffler derivative. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 135, 109867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, M.; Roy, K.B.; Kapitaniak, T.; Rajagopal, K.; Volos, C. A revisit to the past plague epidemic (India) versus the present COVID-19 pandemic: Fractional-order chaotic. models and fuzzy logic control. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2022, 231, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahloul, M.A.; Chahid, A.; Laleg-Kirati, T.-M. Fractional-order SEIQRDP model for simulating the dynamics of COVID-19 epidemic. IEEE Open J. Eng. Med. Biol. 2020, 1, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbouche, N.; Ouannas, A.; Batiha, I.M.; Grassi, G. Chaotic dynamics in a novel COVID-19 pandemic model described by commensurate and incommensurate fractional-order derivatives. Nonlinear Dyn. 2022, 109, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-P.; Bayatti, H.A.; Din, A.; Zeb, A. A vigorous study of fractional-order model via ABC derivatives. Results Phys. 2021, 29, 104737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Atangana, A. Modeling the dynamics of novel coronavirus (2019-NCOV) with fractional derivative. Alex. Eng. J. 2020, 59, 2379–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Abdeljawad, T.; Mahariq, I.; Jarad, F. Qualitative analysis of a mathematical model in the time of COVID-19. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 5098598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A.; Atangana, A.; Khan, Z.A.; Djillali, S. A robust study of a piecewise fractional order COVID-19 mathematical model. Alex. J. Eng. 2022, 61, 5649–5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A.; Kumar, P.; Erturk, V.S.; Sitthiwirattham, T. A new study on two different vaccinated fractional-order COVID-19 models via numerical algorithms. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2022, 34, 101914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zeb, A.; Egbelowo, O.F.; Erturk, V.S. Dynamics of a fractional order mathematical model for COVID-19 epidemic. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Ajou, A.; Abu Arqub, O.; Al Zhour, Z.; Momani, S. New results on fractional power series: Theories and applications. Entropy 2013, 15, 5305–5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, M.; Fabrizio, M. A new definition of fractional derivative without singular kernel. Prog. Fract. Differ. Appl. 2015, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Atangana, A.; Baleanu, D. New fractional derivatives with non-local and non-singular kernel. Therm. Sci. 2016, 20, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattaf, K. A new generalized definition of fractional derivative with non-singular kernel. Computation 2020, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorenflo, R.; Kilbas, A.A.; Mainardi, F.; Rogosin, S.V. Mittag-Leffler Functions, Related Topics and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, I.A.; Yusuf, A.; Nisar, K.S.; Abdel-Aty, A.-H.; Nofal, T.A. Mathematical model to assess the imposition of lockdown during COVID-19 pandemic. Results Phys. 2021, 20, 103716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W. Global existence theory and chaos control of fractional differential equations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2007, 323, 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, O.; Heesterbeek, J.A.P.; Metz, J.A.P. On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio R0 in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. J. Math. Biol. 1990, 28, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matignon, D. Stability Results for Fractional Differential Equations with Applications to Control Processing; Computational Engineering in Systems Applications: Lille, France, 1996; Volume 2, pp. 963–968. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Podlubny, I. Mittag–Leffler stability of fractional order nonlinear dynamic systems. Automatica 2009, 45, 1965–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Podlubny, I. Stability of fractional-order nonlinear dynamic systems: Lyapunov direct method and generalized Mittag–Leffler stability. Comput. Math. Appl. 2010, 59, 1810–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattaf, K. On the stability and numerical scheme of fractional differential equations with application to biology. Computation 2022, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavari, H.; Baleanu, D.; Sadati, J. Stability analysis of Caputo fractional-order nonlinear systems revisited. Nonlinear Dyn. 2012, 67, 2433–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattaf, K. Dynamics of a generalized fractional epidemic model of COVID-19 with carrier effect. Adv. Syst. Sci. Appl. 2022, 22, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, S.; Al-Zoubi, A.; Freihet, A.; Al-Smadi1, M.; Momani, S. Solution of fractional SIR epidemic Model using residual power series method. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 2019, 13, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.M.; Lombardi Junior, L.P.; Castro, F.F.M.; Yang, A.C. Mathematical modeling of the transmission of SARS-CoV-2—Evaluating the impact of isolation in São Paulo State (Brazil) and lockdown in Spain associated with protective measures on the epidemic of COVID-19. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothe, C.; Schunk, M.; Sothmann, P.; Bretzel, G.; Froeschl, G.; Wallrauch, C.; Zimmer, T.; Thiel, V.; Janke, C.; Guggemos, W. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 970–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).