High Vitamin C Status Is Associated with Elevated Mood in Male Tertiary Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Vitamin C Analysis

2.3. Analysis of Mood

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A.J.; Stewart-Brown, S. Is Psychological Well-Being Linked to the Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables? Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, T.S.; Brookie, K.L.; Richardson, A.C.; Polak, M.A. On carrots and curiosity: Eating fruit and vegetables is associated with greater flourishing in daily life. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, A.C.; Chang, T.L.; Chi, S.H. Frequent consumption of vegetables predicts lower risk of depression in older Taiwanese—Results of a prospective population-based study. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishwajit, G.; O’Leary, D.P.; Ghosh, S.; Sanni, Y.; Shangfeng, T.; Zhanchun, F. Association between depression and fruit and vegetable consumption among adults in South Asia. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujcic, R.; Oswald, J. Evolution of Well-Being and Happiness After Increases in Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rooney, C.; McKinley, M.C.; Woodside, J.V. The potential role of fruit and vegetables in aspects of psychological well-being: A review of the literature and future directions. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, B.J.; Crawford, S.G.; Field, C.J.; Simpson, J.S. Vitamins, minerals, and mood. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, M.; Conry-Cantilena, C.; Wang, Y.; Welch, R.W.; Washko, P.W.; Dhariwal, K.R.; Park, J.B.; Lazarev, A.; Graumlich, J.F.; King, J.; et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: Evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 3704–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandon, J.H.; Lund, C.C.; Dill, D.B. Experimental human scurvy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1940, 223, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englard, S.; Seifter, S. The biochemical functions of ascorbic acid. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1986, 6, 365–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, P.L. Depression: The case for a monoamine deficiency. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2000, 61, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Cullen, J.J.; Buettner, G.R. Ascorbic acid: Chemistry, biology and the treatment of cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1826, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Minor, E.A.; Court, B.L.; Young, J.I.; Wang, G. Ascorbate induces ten-eleven translocation (Tet) methylcytosine dioxygenase-mediated generation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 13669–13674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaschke, K.; Ebata, K.T.; Karimi, M.M.; Zepeda-Martinez, J.A.; Goyal, P.; Mahapatra, S.; Tam, A.; Laird, D.J.; Rao, A.; Lorincz, M.C.; et al. Vitamin C induces Tet-dependent DNA demethylation and a blastocyst-like state in ES cells. Nature 2013, 500, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, T.Y.; Meaney, M.J. Epigenetics and the environmental regulation of the genome and its function. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 439–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindblad, M.; Tveden-Nyborg, P.; Lykkesfeldt, J. Regulation of vitamin C homeostasis during deficiency. Nutrients 2013, 5, 2860–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornig, D. Distribution of ascorbic acid, metabolites and analogues in man and animals. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1975, 258, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, R.E.; Hurley, R.J.; Jones, P.R. The retention of ascorbic acid by guinea-pig tissues. Br. J. Nutr. 1971, 6, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissers, M.C.; Bozonet, S.M.; Pearson, J.F.; Braithwaite, L.J. Dietary ascorbate intake affects steady state tissue concentrations in vitamin C-deficient mice: Tissue deficiency after suboptimal intake and superior bioavailability from a food source (kiwifruit). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gariballa, S. Poor vitamin C status is associated with increased depression symptoms following acute illness in older people. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2014, 84, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheraskin, E.; Ringsdorf, W.M., Jr.; Medford, F.H. Daily vitamin C consumption and fatigability. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1976, 24, 136–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prohan, M.; Amani, R.; Nematpour, S.; Jomehzadeh, N.; Haghighizadeh, M.H. Total antioxidant capacity of diet and serum, dietary antioxidant vitamins intake, and serum hs-CRP levels in relation to depression scales in university male students. Redox Rep. 2014, 19, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, I.J.; de Souza, V.V.; Motta, V.; Da-Silva, S.L. Effects of Oral Vitamin C Supplementation on Anxiety in Students: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 18, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.J.; Robitaille, L.; Eintracht, S.; MacNamara, E.; Hoffer, L.J. Effects of vitamin C and vitamin D administration on mood and distress in acutely hospitalized patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carr, A.C.; Bozonet, S.M.; Pullar, J.M.; Vissers, M.C. Mood improvement in young adult males following supplementation with gold kiwifruit, a high-vitamin C food. J. Nutr. Sci. 2013, 2, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huck, C.J.; Johnston, C.S.; Beezhold, B.L.; Swan, P.D. Vitamin C status and perception of effort during exercise in obese adults adhering to a calorie-reduced diet. Nutrition 2013, 29, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Robitaille, L.; Eintracht, S.; Hoffer, L.J. Vitamin C provision improves mood in acutely hospitalized patients. Nutrition 2011, 27, 530–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNair, D.; MaH, J.W.P. Profile of Mood States Technical Update; North Tonawnada: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, A.C.; Pullar, J.M.; Moran, S.; Vissers, M.C. Bioavailability of vitamin C from kiwifruit in non-smoking males: Determination of ‘healthy’ and ‘optimal’ intakes. J. Nutr. Sci. 2012, 1, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.C.; Bozonet, S.M.; Pullar, J.M.; Simcock, J.W.; Vissers, M.C. A randomized steady-state bioavailability study of synthetic versus natural (kiwifruit-derived) vitamin C. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3684–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lykkesfeldt, J.; Poulsen, H.E. Is vitamin C supplementation beneficial? Lessons learned from randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourre, J.M. Effects of nutrients (in food) on the structure and function of the nervous system: Update on dietary requirements for brain. Part 1: Micronutrients. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2006, 10, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Pinilla, F. Brain foods: The effects of nutrients on brain function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, B.J.; Fisher, J.E.; Crawford, S.G.; Field, C.J.; Kolb, B. Improved mood and behavior during treatment with a mineral-vitamin supplement: An open-label case series of children. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2004, 14, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rucklidge, J.J.; Eggleston, M.J.F.; Johnstone, J.M.; Darling, K.; Frampton, C.M. Vitamin-mineral treatment improves aggression and emotional regulation in children with ADHD: A fully blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 59, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rucklidge, J.; Taylor, M.; Whitehead, K. Effect of micronutrients on behavior and mood in adults With ADHD: Evidence from an 8-week open label trial with natural extension. J. Atten. Disord. 2011, 15, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarris, J.; Logan, A.C.; Akbaraly, T.N.; Amminger, G.P.; Balanza-Martinez, V.; Freeman, M.P.; Hibbeln, J.; Matsuoka, Y.; Mischoulon, D.; Mizoue, T.; et al. Nutritional medicine as mainstream in psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischoulon, D.; Freeman, M.P. Omega-3 fatty acids in psychiatry. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 36, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polak, M.A.; Richardson, A.C.; Flett, J.A.M.; Brookie, K.L.; Conner, T.S. Measuring Mood: Considerations and Innovations for Nutrition Science. In Nutrition for Brain Health and Cognitive Performance; Dye, L., Best, T., Eds.; Taylor Japan and Francis: London, UK, 2015; pp. 93–119. [Google Scholar]

- Diliberto, E.J.; Daniels, A.J., Jr.; Viveros, O.H. Multicompartmental secretion of ascorbate and its dual role in dopamine beta-hydroxylation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 54, 1163S–1172S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehn, S.K.; Kanfer, J.N. Effects of chronic ascorbic acid deficiency on guinea pig lysosomal hydrolase activities. J. Nutr. 1980, 110, 2085–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deana, R.; Bharaj, B.S.; Verjee, Z.H.; Galzigna, L. Changes relevant to catecholamine metabolism in liver and brain of ascorbic acid deficient guinea-pigs. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 1975, 45, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, S.R.; Yoshida-Hiroi, M.; Sotiriou, S.; Levine, M.; Hartwig, H.G.; Nussbaum, R.L.; Eisenhofer, G. Impaired adrenal catecholamine system function in mice with deficiency of the ascorbic acid transporter (SVCT2). FASEB J. 2003, 17, 1928–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, J.M.; Qu, Z.C.; Meredith, M.E. Mechanisms of ascorbic acid stimulation of norepinephrine synthesis in neuronal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 426, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kuzkaya, N.; Weissmann, N.; Harrison, D.G.; Dikalov, S. Interactions of peroxynitrite, tetrahydrobiopterin, ascorbic acid, and thiols: Implications for uncoupling endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 22546–22554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, J.M. Vitamin C transport and its role in the central nervous system. Subcell. Biochem. 2012, 56, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berk, M.; Williams, L.J.; Jacka, F.N.; O‘Neil, A.; Pasco, J.A.; Moylan, S.; Allen, N.B.; Stuart, A.L.; Hayley, A.C.; Byrne, M.L.; et al. So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from? BMC Med. 2013, 11, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udina, M.; Castellvi, P.; Moreno-Espana, J.; Navines, R.; Valdes, M.; Forns, X.; Langohr, K.; Sola, R.; Vieta, E.; Martin-Santos, R. Interferon-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 73, 1128–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, W.; Feng, R.; Yang, Y. Changes in the serum levels of inflammatory cytokines in antidepressant drug-naive patients with major depression. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, S.W.; Kim, Y.K. The role of neuroinflammation and neurovascular dysfunction in major depressive disorder. J. Inflamm. Res. 2018, 11, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, T.; Zhong, S.; Liao, X.; Chen, J.; He, T.; Lai, S.; Jia, Y. A Meta-Analysis of Oxidative Stress Markers in Depression. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.C.; Rosengrave, P.C.; Bayer, S.; Chambers, S.; Mehrtens, J.; Shaw, G.M. Hypovitaminosis C and vitamin C deficiency in critically ill patients despite recommended enteral and parenteral intakes. Crit Care 2017, 21, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.C.; Maggini, S. Vitamin C and Immune Function. Nutrients 2017, 9, e1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, C.S.; Solomon, R.E.; Corte, C. Vitamin C status of a campus population: College students get a C minus. J. Am. Coll. Health 1998, 46, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczuko, M.; Seidler, T.; Stachowska, E.; Safranow, K.; Olszewska, M.; Jakubowska, K.; Gutowska, I.; Chlubek, D. Influence of daily diet on ascorbic acid supply to students. Roczniki Państwowego Zakładu Higieny 2014, 65, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cahill, L.; Corey, P.N.; El-Sohemy, A. Vitamin C deficiency in a population of young Canadian adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 170, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pullar, J.M.; Bayer, S.; Carr, A.C. Appropriate Handling, Processing and Analysis of Blood Samples Is Essential to Avoid Oxidation of Vitamin C to Dehydroascorbic Acid. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant Characteristics | Mean ± SD | 95% CI | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 21.2 ± 2.5 | 20.8, 21.6 | - |

| Ethnicity | - | - | - |

| Maori | - | - | 13 (9) |

| NZ European | - | - | 106 (76) |

| Weight (kg) | 81.6 ± 15.9 | 78.9, 84.3 | - |

| Height (cm) | 180 ± 7.3 | 178.8, 181.3 | - |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.1 ± 4.3 | 24.4, 25.8 | - |

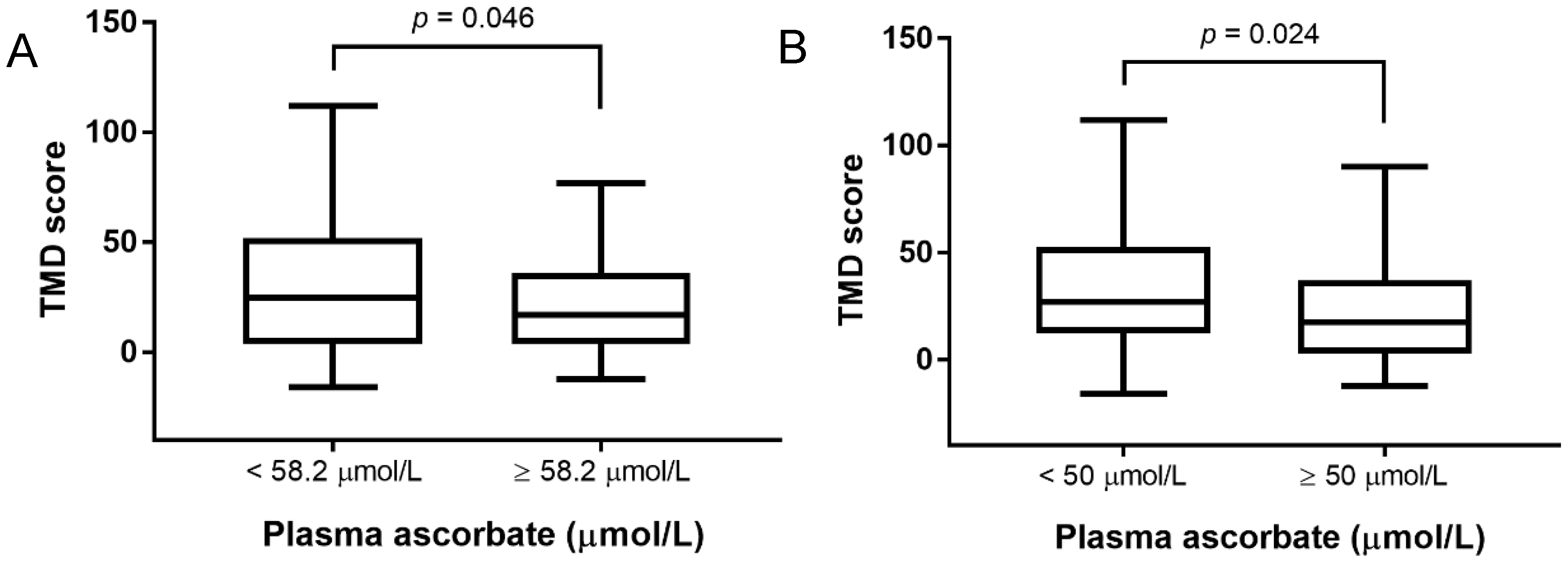

| Vitamin C (µmol/L) | 58.2 ± 18.6 | 55.1, 61.3 | - |

| Adequate | - | - | 99 (71) |

| Inadequate | - | - | 36 (26) |

| Marginal | - | - | 3 (2) |

| Deficient | - | - | 1 (0.7) |

| TMD score | 25.5 ± 26.6 | 21.0, 30.0 | - |

| POMS Subscore | r | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Total mood disturbance | −0.181 | 0.034 |

| Depression | −0.192 | 0.024 |

| Fatigue | −0.061 | 0.480 |

| Tension | −0.098 | 0.255 |

| Anger | −0.172 | 0.044 |

| Vigour | 0.100 | 0.245 |

| Confusion | −0.148 | 0.084 |

| POMS Subscore | p Value |

|---|---|

| Total mood disturbance | 0.024 |

| Depression | 0.012 |

| Fatigue | 0.235 |

| Tension | 0.195 |

| Anger | 0.131 |

| Vigour | 0.453 |

| Confusion | 0.022 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pullar, J.M.; Carr, A.C.; Bozonet, S.M.; Vissers, M.C.M. High Vitamin C Status Is Associated with Elevated Mood in Male Tertiary Students. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox7070091

Pullar JM, Carr AC, Bozonet SM, Vissers MCM. High Vitamin C Status Is Associated with Elevated Mood in Male Tertiary Students. Antioxidants. 2018; 7(7):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox7070091

Chicago/Turabian StylePullar, Juliet M., Anitra C. Carr, Stephanie M. Bozonet, and Margreet C. M. Vissers. 2018. "High Vitamin C Status Is Associated with Elevated Mood in Male Tertiary Students" Antioxidants 7, no. 7: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox7070091

APA StylePullar, J. M., Carr, A. C., Bozonet, S. M., & Vissers, M. C. M. (2018). High Vitamin C Status Is Associated with Elevated Mood in Male Tertiary Students. Antioxidants, 7(7), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox7070091