High-Altitude Hypoxia Injury: Systemic Mechanisms and Intervention Strategies on Immune and Inflammatory Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hypoxia Definition and Classification

3. Co-Related Mechanisms of Hypoxia-Induced Injury in the Body

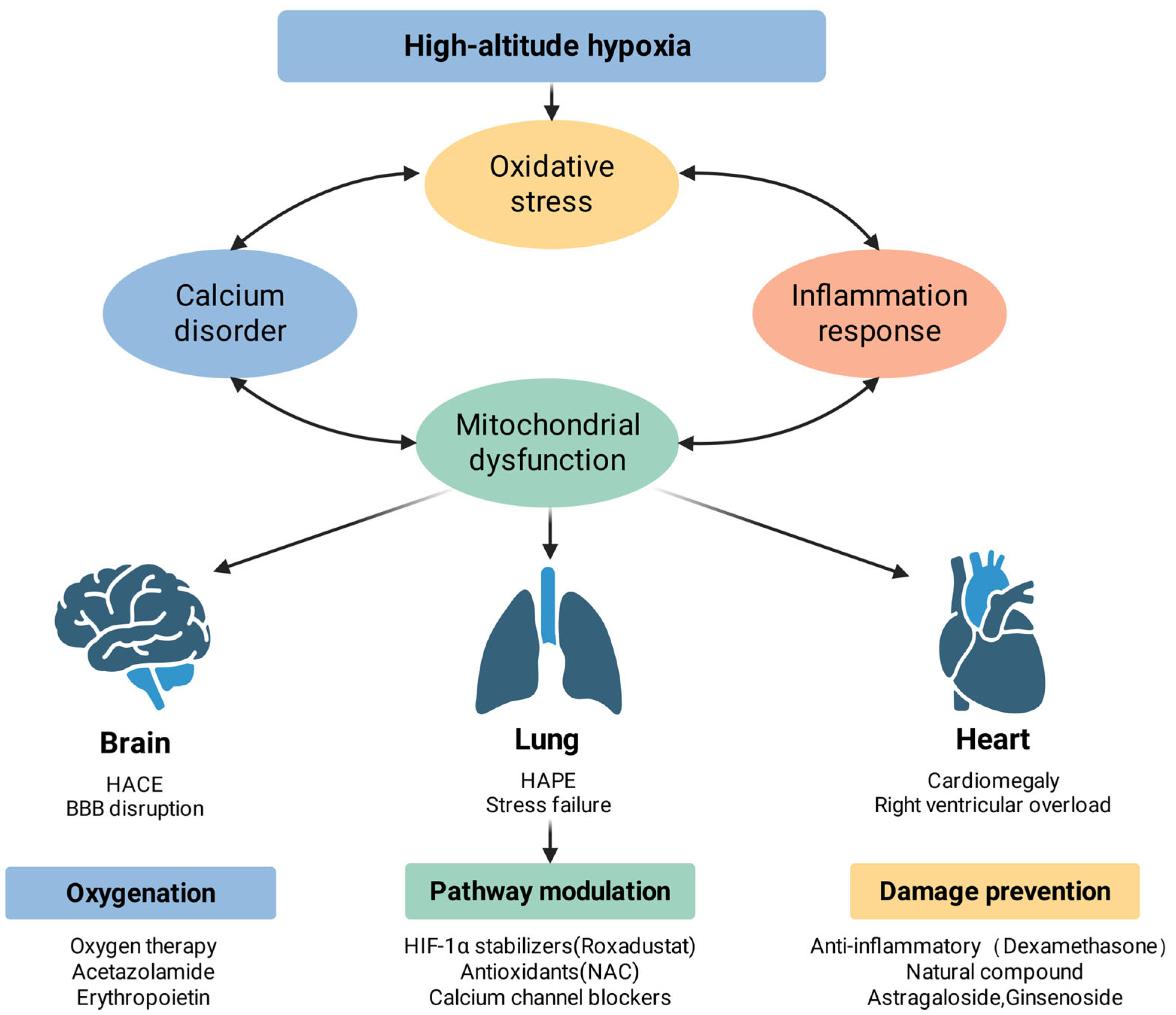

3.1. Oxidative Stress and ROS Signaling

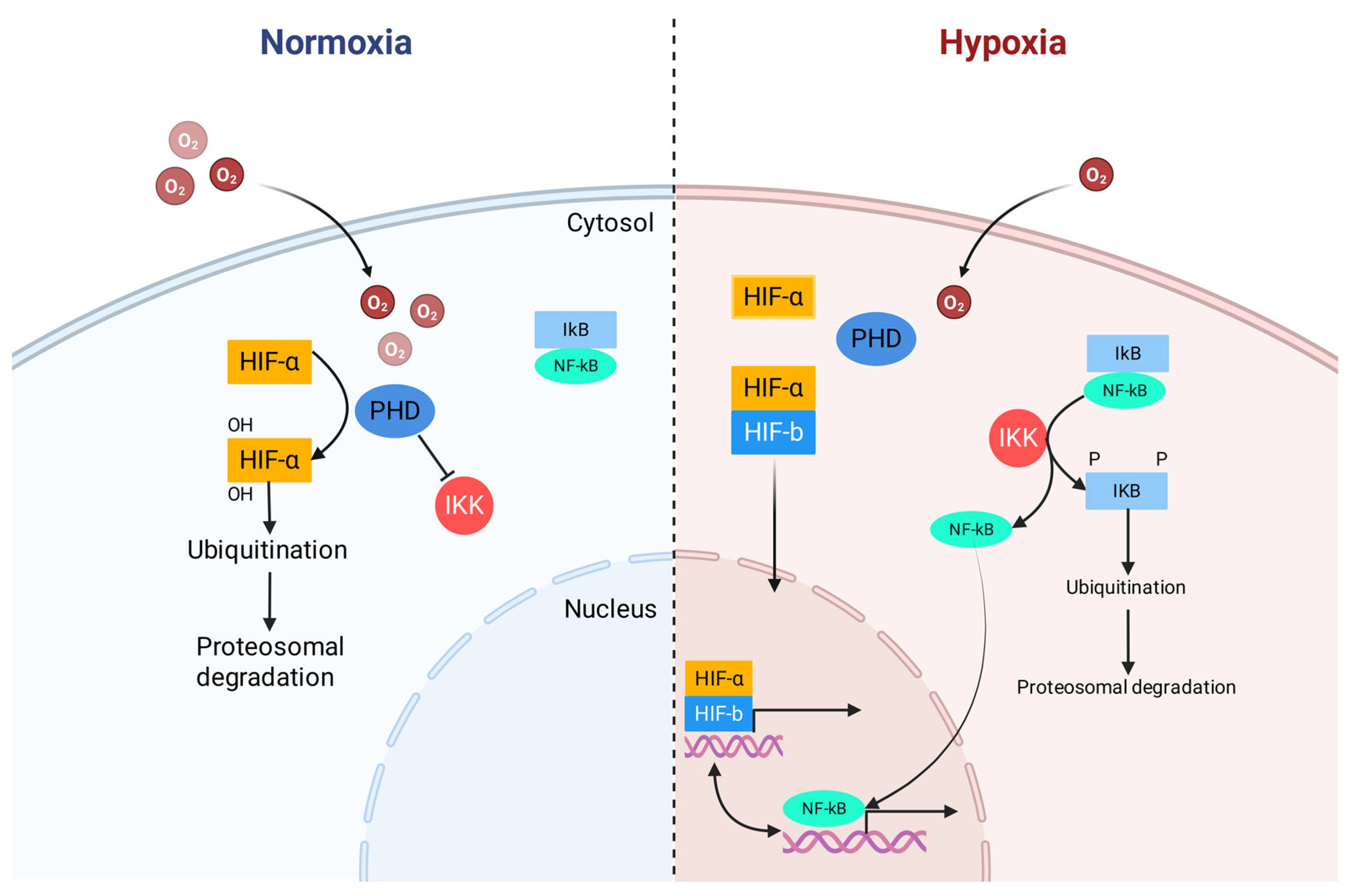

3.2. NF-κB and NLRP3-Mediated Inflammation

3.3. Disruption of Calcium Homeostasis

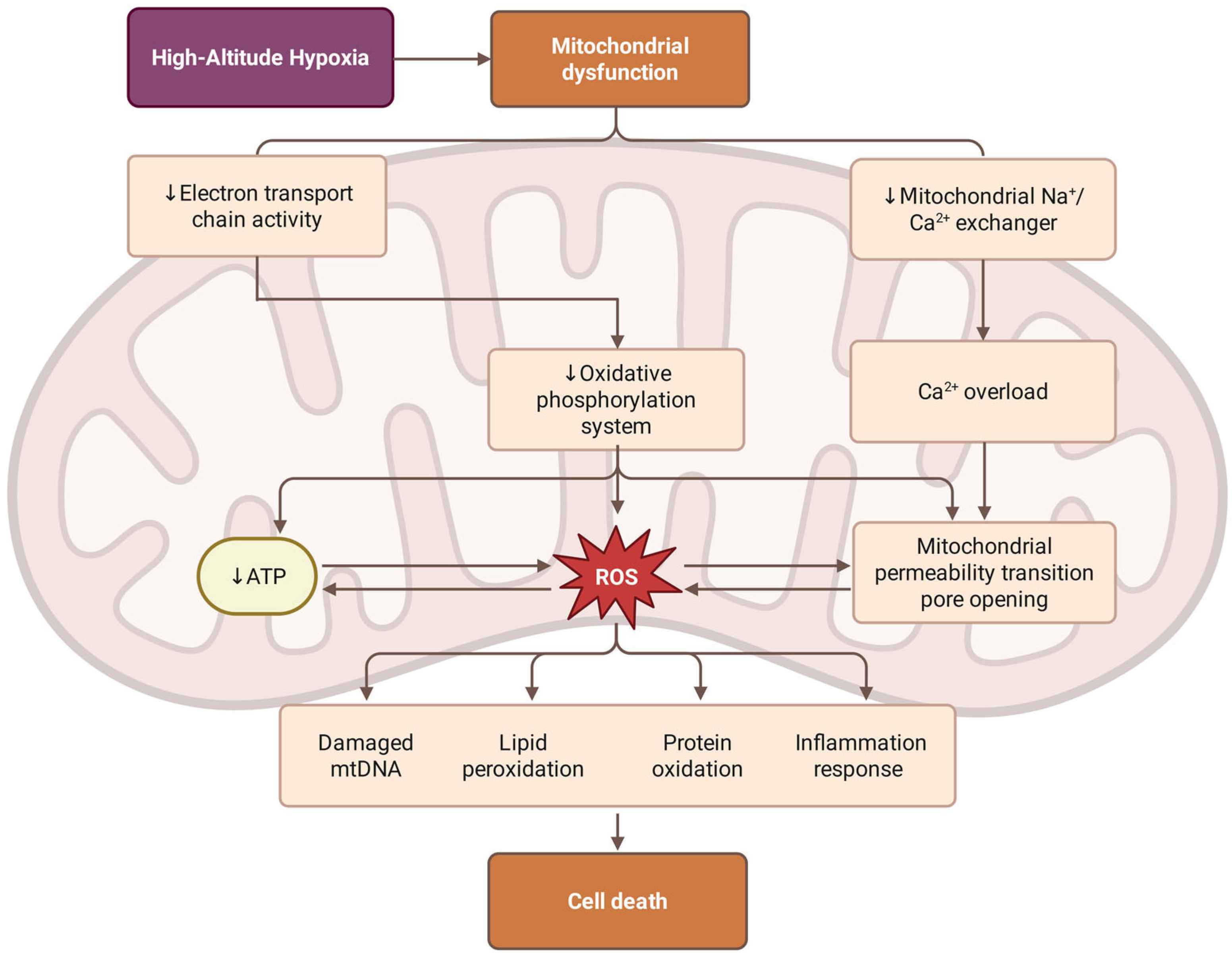

3.4. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

3.5. Nitric Oxide and Erythropoietin Regulation in Hypoxia

3.6. Organ Pathology and Complex Syndromes

3.6.1. Brain Pathology: High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE)

3.6.2. Pulmonary Pathology: High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE)

3.6.3. Cardiac Pathology: High-Altitude Heart Disease

3.6.4. Systemic Integration and Co-Related Amplification

4. Intervention Strategies for Damage Prevention

4.1. Oxygen Supplementation Strategies

4.1.1. External Oxygen Supply

4.1.2. Internal Oxygen Enhancement

4.1.3. Mitochondrial Function Optimization

4.2. Midstream Intervention and Modulation

4.2.1. HIF-1α Pathway Modulation

4.2.2. Antioxidant and NOX Inhibition

4.2.3. Calcium Homeostasis Regulation

4.3. Anti-Inflammation Interventions and Damage Repair

4.3.1. NF-κB Inhibition and Cytokine Control

4.3.2. Damage Prevention

5. Conclusions and Prospect

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMS | Acute Mountain Sickness |

| HAPE | High-altitude Pulmonary Edema |

| HACE | High-altitude Cerebral Edema |

| CMS | Chronic Mountain Sickness |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain-associated protein 3 |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| HBOT | Hyperbaric oxygen therapy |

| ETC | Electron transport chain |

| NAC | N-acetylcysteine |

| GB | Ginkgolide B |

| ECCG | Epigallocatechin gallate |

| XO | Xanthine Oxidase |

| DAMPs | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| mPTP | Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore |

| HIF | Hypoxia-inducible factor |

| NOX | NADPH oxidases |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| SERCA | Sarcoplasmic/Endoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+-ATPase |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α |

| PHD | Prolyl hydroxylase |

References

- Luks, A.M.; Hackett, P.H. Medical Conditions and High-Altitude Travel. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N.; Stacey, M.; Woods, D. Energy at High Altitude. BMJ Mil. Health 2011, 157, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramchandani, R.; Florica, I.T.; Zhou, Z.; Alemi, A.; Baranchuk, A. Review of Athletic Guidelines for High-Altitude Training and Acclimatization. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2024, 25, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydykov, A.; Mamazhakypov, A.; Maripov, A.; Kosanovic, D.; Weissmann, N.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Sarybaev, A.S.; Schermuly, R.T. Pulmonary Hypertension in Acute and Chronic High Altitude Maladaptation Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, P.M. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 2361–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatterer, H.; Villafuerte, F.C.; Ulrich, S.; Bhandari, S.S.; Keyes, L.E.; Burtscher, M. Altitude Illnesses. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, J.B. High-Altitude Medicine. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Li, B.; Shi, X.; Chen, Y.; Pan, S.; Lin, Z.; Gu, Z.; Hailer, F.; Hu, L.; Zhan, X. Homeostasis of Glucose and Lipid Metabolism during Physiological Responses to a Simulated Hypoxic High Altitude Environment. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midha, A.D.; Zhou, Y.; Queliconi, B.B.; Barrios, A.M.; Haribowo, A.G.; Chew, B.T.L.; Fong, C.O.Y.; Blecha, J.E.; VanBrocklin, H.; Seo, Y.; et al. Organ-Specific Fuel Rewiring in Acute and Chronic Hypoxia Redistributes Glucose and Fatty Acid Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 504–516.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richalet, J.P.; Hermand, E.; Lhuissier, F.J. Cardiovascular Physiology and Pathophysiology at High Altitude. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, E.; El Alam, S.; Siques, P.; Brito, J. Oxidative Stress and Diseases Associated with High-Altitude Exposure. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, J.; Franklin, C. Hypoxemia and Hypoxia. In Common Surgical Diseases: An Algorithmic Approach to Problem Solving; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 391–394. ISBN 978-0-387-75246-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nakane, M. Biological Effects of the Oxygen Molecule in Critically Ill Patients. J. Intensive Care 2020, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.B.; Luks, A.M. West’s Pulmonary Pathophysiology: The Essentials, 9th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer bu: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4963-3944-7. [Google Scholar]

- Khonsary, S. Guyton and Hall: Textbook of Medical Physiology. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2017, 8, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whayne, T.F. Cardiovascular Medicine at High Altitude. Angiology 2014, 65, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Self, A.A.; Mesarwi, O.A. Intermittent Versus Sustained Hypoxemia from Sleep-Disordered Breathing. Sleep Med. Clin. 2024, 19, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, N.B. Carboxyhemoglobin: A Primer for Clinicians. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 2018, 45, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busl, K.M.; Greer, D.M. Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury: Pathophysiology, Neuropathology and Mechanisms. Neurorehabilitation 2010, 26, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.C. Anemia and Brain Hypoxia. Blood 2023, 141, 327–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, J.A.; Smith, C.A. Pathophysiology of Human Ventilatory Control. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubin, A.; Estenssoro, E. Mechanisms of Tissue Hypercarbia in Sepsis. Front. Biosci. 2008, 13, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aboul-Enein, F.; Lassmann, H. Mitochondrial Damage and Histotoxic Hypoxia: A Pathway of Tissue Injury in Inflammatory Brain Disease? Acta Neuropathol. 2005, 109, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Akhter, Y.; Chatterjee, S. A Review on Remediation of Cyanide Containing Industrial Wastes Using Biological Systems with Special Reference to Enzymatic Degradation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luks, A.M.; Swenson, E.R.; Bärtsch, P. Acute High-Altitude Sickness. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2017, 26, 160096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.D.; Vincent, A.L. High Altitude Cerebral Edema. In Statpearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- López-Barneo, J. Neurobiology of the Carotid Body. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2022, 188, 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, K.; Jolly, M.K. Acute vs. Chronic vs. Cyclic Hypoxia: Their Differential Dynamics, Molecular Mechanisms, and Effects on Tumor Progression. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafuerte, F.C.; Simonson, T.S.; Bermudez, D.; León-Velarde, F. High-Altitude Erythrocytosis: Mechanisms of Adaptive and Maladaptive Responses. Physiology 2022, 37, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.C.; Seltz, L.M.; Yates, P.A.; Peirce, S.M. Chronic Whole-Body Hypoxia Induces Intussusceptive Angiogenesis and Microvascular Remodeling in the Mouse Retina. Microvasc. Res. 2010, 79, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Higgins, D.F.; Kimura, K.; Bernhardt, W.M.; Shrimanker, N.; Akai, Y.; Hohenstein, B.; Saito, Y.; Johnson, R.S.; Kretzler, M.; Cohen, C.D.; et al. Hypoxia Promotes Fibrogenesis in Vivo via HIF-1 Stimulation of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 3810–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushchak, V.I.; Storey, K.B. Oxidative Stress Concept Updated: Definitions, Classifications and Regulatory Pathways Implicated. EXCLI J. 2021, 20, 956–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakonyi, T.; Radak, Z. High Altitude and Free Radicals. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2004, 3, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cioffi, D.L. Redox Regulation of Endothelial Canonical Transient Receptor Potential Channels. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 1567–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malczyk, M.; Veith, C.; Schermuly, R.T.; Gudermann, T.; Dietrich, A.; Sommer, N.; Weissmann, N.; Pak, O. NADPH Oxidases—Do They Play a Role in TRPC Regulation under Hypoxia? Pflügers Arch.-Eur. J. Physiol. 2016, 468, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedard, K.; Krause, K.H. The NOX Family of ROS-Generating NADPH Oxidases: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 245–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickneson, K.; George, J. Xanthine Oxidoreductase Inhibitors. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, B.; Benoit, B.; Brand, M.D. Hypoxia Decreases Mitochondrial ROS Production in Cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 224, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira-Mejía, B.; Calderon-Romero, R.; Ordaya-Fierro, J.; Medina, C.; Rodríguez, J.L.; Romero, A.; Dávila, R.; Ramos-Gonzalez, M. Impact of Exposure Duration to High-Altitude Hypoxia on Oxidative Homeostasis in Rat Brain Regions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.G.; Wen, J.; Zhang, X.S.; Jiang, D.C. Association between Decreased Osteopontin and Acute Mountain Sickness upon Rapid Ascent to 3500 m among Young Chinese Men. J. Travel Med. 2018, 25, tay075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ma, S.; Qu, M.; Li, N.; Sun, X.; Wang, T.; Chen, L.; Zhu, J.; Ding, Y.; Gong, Y.; et al. Parthanatos Initiated by ROS-Induced DNA Damage Is Involved in Intestinal Epithelial Injury during Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, A.G.; Schadt, E.E. The Role of Macromolecular Damage in Aging and Age-Related Disease. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69, S28–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubata, T. Involvement of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in BCR Signaling as a Second Messenger. In B Cells in Immunity and Tolerance; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaus, U.G. Oxidants in Physiological Processes. In Reactive Oxygen Species: Network Pharmacology and Therapeutic Applications; Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.J.; Liu, Z. Crosstalk of Reactive Oxygen Species and NF-κB Signaling. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Luo, Y.F.; Wang, Y.S.; Yang, Q.; Xiao, Y.L.; Cai, H.R.; Xie, C.M. Using ROS as a Second Messenger, NADPH Oxidase 2 Mediates Macrophage Senescence via Interaction with NF-κB during Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Infection. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 9741838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltzschig, H.K.; Carmeliet, P. Hypoxia and Inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, K.; Parikh, K.; Heinrich, E.C. Hypoxia and Inflammation: Insights from High-Altitude Physiology. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 676782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingappan, K. NF-κB in Oxidative Stress. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2018, 7, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Uden, P.; Kenneth, N.S.; Rocha, S. Regulation of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α by NF-κB. Biochem. J. 2008, 412, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Chen, H.; Chai, Y. Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs) Induce Apoptosis of Fibroblasts by Activation of NLRP3 Inflammasome via Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Signaling Pathway. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 7499–7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picca, A.; Calvani, R.; Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Landi, F.; Bernabei, R.; Marzetti, E. Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, and Neuroinflammation: Intertwined Roads to Neurodegeneration. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Tate, M.; Mathew, G.; Vince, J.E.; Ritchie, R.H.; de Haan, J.B. Oxidative Stress and NLRP3-Inflammasome Activity as Significant Drivers of Diabetic Cardiovascular Complications: Therapeutic Implications. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.Y.; Bu, Y.R.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.M.; Feng, T.X.; Li, P.J.; Zhao, Y.X.; Ge, Y.L.; Xie, M.J. Acute High-Altitude Hypoxia Induced NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cells by BMAL1 Targeting Mitochondrial VDAC1-Mediated MtDNA Leakage. Apoptosis 2025, 30, 2225–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, D.; Leclercq, G.; Goossens, V.; Vanden Berghe, T.; Van Hamme, E.; Vandenabeele, P.; Lefebvre, R.A. Mitochondria and NADPH Oxidases Are the Major Sources of TNF-α/Cycloheximide-Induced Oxidative Stress in Murine Intestinal Epithelial MODE-K Cells. Cell. Signal. 2015, 27, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, J.; Lambeth, J.D. Nox Enzymes from Fungus to Fly to Fish and What They Tell Us about Nox Function in Mammals. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1342–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Huang, D.; Tang, C.; Zeng, M.; Hu, X. PFKL, a Novel Regulatory Node for NOX2-Dependent Oxidative Burst and NETosis. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. B 2022, 23, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.T.; Bi, Y.H.; Gao, Y.Q.; Huang, R.; Hao, K.; Xu, G.; Tang, J.W.; Ma, Z.Q.; Kong, F.P.; Coote, J.H.; et al. Systemic Pro-Inflammatory Response Facilitates the Development of Cerebral Edema during Short Hypoxia. J. Neuroinflamm. 2016, 13, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Buonfiglio, F.; Li, J.; Pfeiffer, N.; Gericke, A. Mechanisms Underlying Vascular Inflammaging: Current Insights and Potential Treatment Approaches. Aging Dis. 2025, 16, 1889–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, M.J.; Bootman, M.D.; Roderick, H.L. Calcium Signalling: Dynamics, Homeostasis and Remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.P.; Wei, S.; Wei, L.P.; Verkhratsky, A. Calcium Signaling in Physiology and Pathophysiology. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2006, 27, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagur, R.; Hajnóczky, G. Intracellular Ca2+ Sensing: Its Role in Calcium Homeostasis and Signaling. Mol. Cell 2017, 66, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muddapu, V.R.; Chakravarthy, V.S. Influence of Energy Deficiency on the Subcellular Processes of Substantia Nigra Pars Compacta Cell for Understanding Parkinsonian Neurodegeneration. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, N.; Trebak, M. Crosstalk between Calcium and Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling in Cancer. Cell Calcium 2017, 63, 70–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielecińska, A.; Kciuk, M.; Kontek, R. The Impact of Calcium Overload on Cellular Processes: Exploring Calcicoptosis and Its Therapeutic Potential in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Tan, J.; Miao, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, Q. Role of Ca2+ and Ion Channels in the Regulation of Apoptosis under Hypoxia. Histol. Histopathol. 2018, 33, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Ran, P.; Lu, W.; Zhong, N.; Wang, J. Acute Hypoxia Activates Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry and Increases Intracellular Ca2+ Concentration in Rat Distal Pulmonary Venous Smooth Muscle Cells. J. Thorac. Dis. 2013, 5, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, K.M.; von Reyn, C.R.; Bian, J.; Telling, G.C.; Meaney, D.F.; Saatman, K.E. Brain Injury-induced Proteolysis Is Reduced in a Novel Calpastatin-overexpressing Transgenic Mouse. J. Neurochem. 2013, 125, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, G.; Duchen, M.R. Investigating the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore in Disease Phenotypes and Drug Screening. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2019, 85, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardi, P.; Gerle, C.; Halestrap, A.P.; Jonas, E.A.; Karch, J.; Mnatsakanyan, N.; Pavlov, E.; Sheu, S.S.; Soukas, A.A. Identity, Structure, and Function of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore: Controversies, Consensus, Recent Advances, and Future Directions. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 1869–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelova, P.R.; Abramov, A.Y. Interplay of Mitochondrial Calcium Signalling and Reactive Oxygen Species Production in the Brain. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2024, 52, 1939–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nicolo, B.; Cataldi-Stagetti, E.; Diquigiovanni, C.; Bonora, E. Calcium and Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling Interplays in Cardiac Physiology and Pathologies. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, P.S.; Yoon, Y.; Robotham, J.L.; Anders, M.W.; Sheu, S.S. Calcium, ATP, and ROS: A Mitochondrial Love-Hate Triangle. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2004, 287, C817–C833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claverol, M.; Garijo, D.; Grima, C.I.; Márquez, A.; Seara, C. Stabbers of Line Segments in the Plane. Comput. Geom. 2011, 44, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, R.G.; Cerpa, W. Building a Bridge Between NMDAR-Mediated Excitotoxicity and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Chronic and Acute Diseases. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 41, 1413–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endlicher, R.; Drahota, Z.; Štefková, K.; Červinková, Z.; Kučera, O. The Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore—Current Knowledge of Its Structure, Function, and Regulation, and Optimized Methods for Evaluating Its Functional State. Cells 2023, 12, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullaev, I.; Gayibov, U.; Omonturdiev, S.; Fotima, S.; Gayibova, S.; Aripov, T. Molecular Pathways in Cardiovascular Disease under Hypoxia: Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Targets. J. Biomed. Res. 2025, 39, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriadis, T.; Pissas, G.; Liakopoulos, V.; Stefanidis, I. Cytochrome c as a Potentially Clinical Useful Marker of Mitochondrial and Cellular Damage. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Nuevo, A.; Díaz-Ramos, A.; Noguera, E.; Díaz-Sáez, F.; Duran, X.; Muñoz, J.P.; Romero, M.; Plana, N.; Sebastián, D.; Tezze, C.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA and TLR9 Drive Muscle Inflammation upon Opa1 Deficiency. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e96553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipina, C.; Hundal, H.S. The Endocannabinoid System: ‘NO’ Longer Anonymous in the Control of Nitrergic Signalling? J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 9, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric Oxide Synthases: Regulation and Function. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Su, W.; Bao, Q.; Cui, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Yang, C.; Wang, C.; Jiao, L.; Chen, D.; et al. Nitric Oxide Ameliorates the Effects of Hypoxia in Mice by Regulating Oxygen Transport by Hemoglobin. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2024, 25, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umbrello, M.; Dyson, A.; Feelisch, M.; Singer, M. The Key Role of Nitric Oxide in Hypoxia: Hypoxic Vasodilation and Energy Supply–Demand Matching. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 19, 1690–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levett, D.Z.; Fernandez, B.O.; Riley, H.L.; Martin, D.S.; Mitchell, K.; Leckstrom, C.A.; Ince, C.; Whipp, B.J.; Mythen, M.G.; Montgomery, H.E.; et al. The Role of Nitrogen Oxides in Human Adaptation to Hypoxia. Sci. Rep. 2011, 1, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belenichev, I.; Popazova, O.; Bukhtiyarova, N.; Savchenko, D.; Oksenych, V.; Kamyshnyi, O. Modulating Nitric Oxide: Implications for Cytotoxicity and Cytoprotection. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, T.; Iwamura, Y.; Kato, K.; Hirano, I.; Matsumoto, Y.; Tomioka, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Suzuki, N. Drugs Activating Hypoxia-Inducible Factors Correct Erythropoiesis and Hepcidin Levels via Renal EPO Induction in Mice. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 3793–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarelli, C.; Angeletti, A.; Cravedi, P. Erythropoietin, a Multifaceted Protein with Innate and Adaptive Immune Modulatory Activity. Am. J. Transplant. 2019, 19, 2407–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, C.M. Andean, Tibetan, and Ethiopian Patterns of Adaptation to High-Altitude Hypoxia. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2006, 46, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, C.M.; Cavalleri, G.L.; Deng, L.; Elston, R.C.; Gao, Y.; Knight, J.; Li, C.; Li, J.C.; Liang, Y.; McCormack, M.; et al. Natural Selection on EPAS1(HIF2α) Associated with Low Hemoglobin Concentration in Tibetan Highlanders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11459–11464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassmann, M.; Muckenthaler, M.U. Adaptation of Iron Requirement to Hypoxic Conditions at High Altitude. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 119, 1432–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizcardo-Galindo, G.; León-Velarde, F.; Villafuerte, F.C. High-Altitude Hypoxia Decreases Plasma Erythropoietin Soluble Receptor Concentration in Lowlanders. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2020, 21, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtscher, J.; Gatterer, H.; Beidleman, B.A.; Burtscher, M. Dexamethasone for Prevention of AMS, HACE, and HAPE and for Limiting Impairment of Performance after Rapid Ascent to High Altitude: A Narrative Review. Mil. Med. Res. 2025, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berek, K.; Berek, A.; Bauer, A.; Rudzki, D.; Di Pauli, F.; Bsteh, G.; Ponleitner, M.; Treml, B.; Kleinsasser, A.; Berger, T.; et al. High erythropoietin levels are associated with low neurofilament light levels in simulated high altitude: A further hint for neuroprotection by erythropoietin. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1608763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loyrion, E. Viscosité Sanguine et Fonction Cardio-Vasculaire Chez Des Résidents de Haute Altitude. 2018. Available online: https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02420663v1 (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Yu, J.J.; Non, A.L.; Heinrich, E.C.; Gu, W.; Alcock, J.; Moya, E.A.; Lawrence, E.S.; Tift, M.S.; O’Brien, K.A.; Storz, J.F.; et al. Time Domains of Hypoxia Responses and -Omics Insights. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 885295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafuente, J.V.; Bermudez, G.; Camargo-Arce, L.; Bulnes, S. Blood-Brain Barrier Changes in High Altitude. CNS Neurol. Disord.-Drug Targets-CNS Neurol. Disord. 2016, 15, 1188–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Alshakhshir, N.; Zhao, L. Glycolytic Metabolism, Brain Resilience, and Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 662242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lochhead, J.J.; McCaffrey, G.; Quigley, C.E.; Finch, J.; DeMarco, K.M.; Nametz, N.; Davis, T.P. Oxidative Stress Increases Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability and Induces Alterations in Occludin during Hypoxia–Reoxygenation. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010, 30, 1625–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Jin, Q.; Zheng, X.; Mo, L.; Da, Z. Oxygen Metabolism Abnormalities and High-Altitude Cerebral Edema. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1555910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Qiu, R.; Tang, Q.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Qin, Y.; Li, Q.; Yao, J.; Jiang, Z.; Xu, H.; et al. Exosomes from High-Altitude Cerebral Edema Patients Induce Cognitive Dysfunction by Altering Oxidative Stress Responses in Mice. Transl. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baburamani, A.A.; Ek, C.J.; Walker, D.W.; Castillo-Melendez, M. Vulnerability of the Developing Brain to Hypoxic-Ischemic Damage: Contribution of the Cerebral Vasculature to Injury and Repair? Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbuena, P.; Li, W.; Ehrich, M. Assessments of Tight Junction Proteins Occludin, Claudin 5 and Scaffold Proteins ZO1 and ZO2 in Endothelial Cells of the Rat Blood–Brain Barrier: Cellular Responses to Neurotoxicants Malathion and Lead Acetate. Neurotoxicology 2011, 32, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Ren, B.; Gao, Y. Tight Junction Proteins Related to Blood-Brain Barrier and Their Regulatory Signaling Pathways in Ischemic Stroke. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paralikar, S. High Altitude Pulmonary Edema-Clinical Features, Pathophysiology, Prevention and Treatment. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 16, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunham-Snary, K.J.; Wu, D.; Sykes, E.A.; Thakrar, A.; Parlow, L.R.G.; Mewburn, J.D.; Parlow, J.L.; Archer, S.L. Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction. Chest 2017, 151, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.; Sommer, N.; Cox-Flaherty, K.; Weissmann, N.; Ventetuolo, C.E.; Maron, B.A. Pulmonary Hypertension: A Contemporary Review. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 208, 528–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Mathieu-Costello, O. High Altitude Pulmonary Edema Is Caused by Stress Failure of Pulmonary Capillaries. Int. J. Sports Med. 1992, 13, S54–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Zheng, X.; Lin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, Y. Mechanotransduction Regulates the Interplays Between Alveolar Epithelial and Vascular Endothelial Cells in Lung. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 818394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, J.; Westphalen, K. Macrophage-Epithelial Interactions in Pulmonary Alveoli. Semin. Immunopathol. 2016, 38, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiber, A.; Xia, N.; Steven, S.; Oelze, M.; Hanf, A.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Münzel, T.; Li, H. New Therapeutic Implications of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase (eNOS) Function/Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, K.D.; Snyder, C.A.; Coulombe, K.L.K. Cardiomyocytes in Hypoxia: Cellular Responses and Implications for Cell-Based Cardiac Regenerative Therapies. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, S.; Dunham-Snary, K.; Bentley, R.; Alizadeh, E.; Weir, E. Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction: An Important Component of the Homeostatic Oxygen Sensing System. Physiol. Res. 2024, 73, S493–S510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Morales, J.-C.; Hua, W.; Yao, Y.; Morad, M. Regulation of Ca2+ Signaling by Acute Hypoxia and Acidosis in Cardiomyocytes Derived from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Calcium 2019, 78, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstetter, L.; Scherrer, U.; Rimoldi, S.F. Going to High Altitude with Heart Disease. Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamazhakypov, A.; Sartmyrzaeva, M.; Kushubakova, N.; Duishobaev, M.; Maripov, A.; Sydykov, A.; Sarybaev, A. Right Ventricular Response to Acute Hypoxia Exposure: A Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2022, 12, 786954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luks, A.M.; Beidleman, B.A.; Freer, L.; Grissom, C.K.; Keyes, L.E.; McIntosh, S.E.; Rodway, G.W.; Schoene, R.B.; Zafren, K.; Hackett, P.H. Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Acute Altitude Illness: 2024 Update. Wild. Environ. Med. 2024, 35, 2S–19S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bärtsch, P.; Swenson, E. High Altitude Pulmonary Oedema. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2003, 133, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhu, Y.P.; Su, R.; Li, H.; Pan, Y.Y. Hyperbaric Intervention Ameliorates the Negative Effects of Long-Term High-Altitude Exposure on Cognitive Control Capacity. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1378987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Zhang, D.; Ma, H. Single Hyperbaric Oxygen Intervention Improves Attention Networks in High Altitude Migrants. Physiol. J. 2021, 73, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, C.M.; Kenefick, R.W.; Petrassi, F.A.; Muza, S.R.; Charkoudian, N. Altitude, Acute Mountain Sickness, and Acetazolamide: Recommendations for Rapid Ascent. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2021, 22, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbuskaite, D.; Oernbo, E.K.; Wardman, J.H.; Toft-Bertelsen, T.L.; Conti, E.; Andreassen, S.N.; Gerkau, N.J.; Rose, C.R.; MacAulay, N. Acetazolamide Modulates Intracranial Pressure Directly by Its Action on the Cerebrospinal Fluid Secretion Apparatus. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022, 19, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzurum, S.C.; Ghosh, S.; Janocha, A.J.; Xu, W.; Bauer, S.; Bryan, N.S.; Tejero, J.; Hemann, C.; Hille, R.; Stuehr, D.J.; et al. Higher Blood Flow and Circulating NO Products Offset High-Altitude Hypoxia among Tibetans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 17593–17598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duplain, H.; Sartori, C.; Lepori, M.; Egli, M.; Allemann, Y.; Nicod, P.; Scherrer, U. Exhaled Nitric Oxide in High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 162, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Droma, Y.; Hanaoka, M.; Ota, M.; Katsuyama, Y.; Koizumi, T.; Fujimoto, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Kubo, K. Positive Association of the Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Gene Polymorphisms with High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema. Circulation 2002, 106, 826–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, D.P.; Madery, B.D.; Curry, T.B.; Eisenach, J.H.; Wilkins, B.W.; Joyner, M.J. Nitric Oxide Contributes to the Augmented Vasodilatation during Hypoxic Exercise. J. Physiol. 2010, 588, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggeridge, D.J.; Howe, C.C.F.; Spendiff, O.; Pedlar, C.; James, P.E.; Easton, C. A Single Dose of Beetroot Juice Enhances Cycling Performance in Simulated Altitude. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014, 46, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldeweg, M.L.A.; Medina Feliz, J.X.; Berend, K. Altitude Pre-Acclimatization with an Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agent. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2025, 10, 003792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, A.; Garrido, D.; Banegas, A.; Mena, M.B.; Osorio, W.; Rico-Fontalvo, J.; Raad-Sarabia, M.; Daza-Arnedo, R.; Cardona-Blanco, M.; Rodriguez-Yanez, T.; et al. Living on High Altitudes Associated with Reduced Requirements of Exogenous Erythropoietin in Patients on Chronic Hemodialysis. Rev. Colomb. Nefrol. 2024, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, J.; Sun, M.; Dang, L.; Shestakova, L.; Ostrovsky, Y.; Li, W.; Li, L.; Ding, J. Advanced Oxygen Therapeutics for Treatments of Acute Hemorrhagic Shock and Organ Preservation. Smart Mater. Med. 2025, 6, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Peng, X.Y.; Li, Q.H.; Xiang, X.M.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, Q.G.; Lau, B.; Tzang, F.; Liu, L.M.; et al. The Protective Effect of a Novel Cross-Linked Hemoglobin-Based Oxygen Carrier on Hypoxia Injury of Acute Mountain Sickness in Rabbits and Goats. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 690190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H. Hemoglobin-Based Oxygen Carriers: Where Are We Now in 2023? Medicina 2023, 59, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Tian, Y.; Liu, N.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Yuan, G.; Chang, A.; Chang, X.; Wu, J.; Zhou, H. Mitochondrial Stress as a Central Player in the Pathogenesis of Hypoxia-Related Myocardial Dysfunction: New Insights. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 21, 2502–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; Yin, J.; Chen, J.; Ma, X.; Wu, M.; Liu, G.; Yao, K.; Tan, B.; Yin, Y. Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants: A Step towards Disease Treatment. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 8837893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ye, X.; Liu, Z.; Sun, M.; Yu, S.; Lv, H.; Wu, B.; Zhang, C.; Gu, W.; He, J.; et al. Effect of Ubiquinol on Cardiorespiratory Fitness during High-Altitude Acclimatization and de-Acclimatization in Healthy Adults: The Shigatse CARdiorespiratory Fitness Study Design. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1129144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Shelbayeh, O.; Arroum, T.; Morris, S.; Busch, K.B. PGC-1α Is a Master Regulator of Mitochondrial Lifecycle and ROS Stress Response. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, J. Resveratrol Improved Mitochondrial Biogenesis by Activating SIRT1/PGC-1α Signal Pathway in SAP. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, H.; Gao, Y.; Li, L.; Tang, C.; Wen, G.; Yang, Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhou, M.; Mao, L.; et al. Quercetin Induces Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury via the PGC-1α Signaling Pathway. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 3558–3566. [Google Scholar]

- Abrego-Guandique, D.M.; Aguilera Rojas, N.M.; Chiari, A.; Luciani, F.; Cione, E.; Cannataro, R. The Impact of Exercise on Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Skeletal Muscle: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Biomol. Concepts 2025, 16, 20250055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manalo, D.J.; Rowan, A.; Lavoie, T.; Natarajan, L.; Kelly, B.D.; Ye, S.Q.; Garcia, J.G.N.; Semenza, G.L. Transcriptional Regulation of Vascular Endothelial Cell Responses to Hypoxia by HIF-1. Blood 2005, 105, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Q.; Gu, X.; Zheng, Q.; Zhu, H. Regulatory Mechanism of HIF-1α and Its Role in Liver Diseases: A Narrative Review. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Wang, R.; Zhao, A.; Wang, Z. A Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of the Protective Effects of Roxadustat against Hypoxic Injury at High Altitude. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2023, 17, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedre, B.; Barayeu, U.; Ezeriņa, D.; Dick, T.P. The Mechanism of Action of N-Acetylcysteine (NAC): The Emerging Role of H2S and Sulfane Sulfur Species. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 228, 107916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Gralla, J.; Ordonez, J.G.; Hurtado, M.E.; Swenson, E.R.; Schoene, R.B.; Kelly, J.P.; Callacondo, D.; Rivard, C.; Roncal-Jimenez, C.; et al. Acetazolamide and N-Acetylcysteine in the Treatment of Chronic Mountain Sickness (Monge’s Disease). Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2017, 246, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenório, M.C.D.S.; Graciliano, N.G.; Moura, F.A.; de Oliveira, A.C.M.; Goulart, M.O.F. N-Acetylcysteine (NAC): Impacts on Human Health. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, A.; Bueno-Aventín, E.; Ontañón, I.; Fernádez-Zurbano, P.; Ferreira, V. The Role of Polyphenols in Oxygen Consumption and in the Accumulation of Acetaldehyde and Strecker Aldehydes during Wine Oxidation. Food Chem. 2025, 466, 142242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabetkar, M.; Low, S.Y.; Bradley, N.J.; Jacobs, M.; Naseem, K.M.; Richard Bruckdorfer, K. The Nitration of Platelet Vasodilator Stimulated Phosphoprotein Following Exposure to Low Concentrations of Hydrogen Peroxide. Platelets 2008, 19, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Velalar, C.N.; Ruan, R. Regulating the Age-Related Oxidative Damage, Mitochondrial Integrity, and Antioxidative Enzyme Activity in Fischer 344 Rats by Supplementation of the Antioxidant Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate. Rejuvenation Res. 2008, 11, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Choi, C.I. Black Goji Berry (Lycium Ruthenicum Murray): A Review of Its Pharmacological Activity. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zheng, B.; Li, T.; Liu, R.H. Black Goji Berry Anthocyanins Extend Lifespan and Enhance the Antioxidant Defenses in Caenorhabditis Elegans via the JNK-1 and DAF-16/FOXO Pathways. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 2282–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipriano, A.; Viviano, M.; Feoli, A.; Milite, C.; Sarno, G.; Castellano, S.; Sbardella, G. NADPH Oxidases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Current Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 11632–11655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altenhöfer, S.; Radermacher, K.A.; Kleikers, P.W.M.; Wingler, K.; Schmidt, H.H.H.W. Evolution of NADPH Oxidase Inhibitors: Selectivity and Mechanisms for Target Engagement. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 406–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thannickal, V.J.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K.; Szyndralewiez, C.; Török, N.J. Pre-Clinical Evidence of a Dual NADPH Oxidase 1/4 Inhibitor (Setanaxib) in Liver, Kidney and Lung Fibrosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2023, 27, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajączkowski, S.; Ziółkowski, W.; Badtke, P.; Zajączkowski, M.A.; Flis, D.J.; Figarski, A.; Smolińska-Bylańska, M.; Wierzba, T.H. Promising Effects of Xanthine Oxidase Inhibition by Allopurinol on Autonomic Heart Regulation Estimated by Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Analysis in Rats Exposed to Hypoxia and Hyperoxia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelz, O.; Maggiorini, M.; Ritter, M.; Noti, C.; Waber, U.; Vock, P.; Bärtsch, P. Prevention and Treatment of High Altitude Pulmonary Edema by a Calcium Channel Blocker. Int. J. Sports Med. 1992, 13, S65–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, R.; Iqbal, M.; Basnet, S. Nifedipine for the Treatment of High Altitude Pulmonary Edema. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2012, 23, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Li, M. Protection of Vascular Endothelial Cells Injured by Angiotensin II and Hypoxia In Vitro by Ginkgo Biloba (Ginaton). Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2013, 47, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lei, Q.; Zhao, S.; Xu, W.; Dong, W.; Ran, J.; Shi, Q.; Fu, J. Ginkgolide B Maintains Calcium Homeostasis in Hypoxic Hippocampal Neurons by Inhibiting Calcium Influx and Intracellular Calcium Release. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 627846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Gaynor, R.B. Therapeutic Potential of Inhibition of the NF-κB Pathway in the Treatment of Inflammation and Cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischler, M.; Maggiorini, M.; Dorschner, L.; Debrunner, J.; Bernheim, A.; Kiencke, S.; Mairbäurl, H.; Bloch, K.E.; Naeije, R.; Rocca, H.P.B.L. Dexamethasone but Not Tadalafil Improves Exercise Capacity in Adults Prone to High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 180, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, A.M.; Orlando, R.A. Curcumin and Resveratrol Inhibit Nuclear Factor-kappaB-Mediated Cytokine Expression in Adipocytes. Nutr. Metab. 2008, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Ma, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, F.; Gong, X.; Zhao, J.; Tang, H.; et al. Tetrahydrocurcumin Mitigates Acute Hypobaric Hypoxia-Induced Cerebral Oedema and Inflammation through the NF-κB/VEGF/MMP-9 Pathway. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 2963–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Fang, X.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D.; Chen, Q.; Zhong, G. Astragaloside IV Attenuates Hypoxia-induced Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling via the Notch Signaling Pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Jiao, G.; Chen, Y.; Han, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, W. Astragaloside IV Attenuates Chronic Intermittent Hypoxia-Induced Myocardial Injury by Modulating Ca2+ Homeostasis. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2020, 38, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, M.; Li, C.; Yan, B.; Xu, F.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y. Astragaloside IV Mitigates Hypoxia-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy through Calpain-1-Mediated mTOR Activation. Phytomedicine 2024, 125, 155250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Ren, K.; Wang, L.; Jiang, C.; Yao, Q. Rg1 in Combination with Mannitol Protects Neurons against Glutamate-Induced ER Stress via the PERK-eIF2 α-ATF4 Signaling Pathway. Life Sci. 2020, 263, 118559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Tan, F.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Yin, W. Neuroprotection and Mechanisms of Ginsenosides in Nervous System Diseases: Progress and Perspectives. IUBMB Life 2024, 76, 862–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Liu, Q.P.; An, P.; Jia, M.; Luan, X.; Tang, J.Y.; Zhang, H. Ginsenoside Rd: A Promising Natural Neuroprotective Agent. Phytomedicine 2022, 95, 153883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavero Vargas, A.; Köstlin-Gille, N.; Bauer, R.; Dietz-Ziegler, S.; Lokaj, A.S.; Lutterbach, S.; Gille, C.; Lajqi, T. Hypoxia Supports LPS-Driven Tolerance and Functional Activation in BV-2 Microglial Cells. Biology 2025, 14, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlegel, C.; Liu, K.; Spring, B.; Dietz, S.; Poets, C.F.; Hudalla, H.; Lajqi, T.; Köstlin-Gille, N.; Gille, C. Decreased Expression of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1α (HIF-1α) in Cord Blood Monocytes under Anoxia. Pediatr. Res. 2023, 93, 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type | Primary Defect | Arterial PaO2 | Arterial O2 | Causes (Examples) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxic | Low inspired O2 pressure | Decreased | Decreased | High Altitude, hypoventilation | [16,17] |

| Hypemic | Reduced O2-carrying capacity | Normal | Decreased | Anemia, Carbon monoxide poisoning | [18,19,20] |

| Stagnant | Inadequate tissue perfusion | Normal | Normal | Heart failure, Shock, Vascular occlusion | [21,22] |

| Histotoxic | Impaired cellular O2 utilization | Normal | Normal | Cyanide poisoning | [23,24] |

| Features | Acute Hypoxia | Chronic Hypoxia |

|---|---|---|

| Exposure time | hours to days | months to lifelong exposure |

| Major diseases | Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE), High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) | Chronic Mountain Sickness (CMS), Pulmonary Hypertension, Right Heart Failure |

| Underlying Mechanisms | Rapid nerve and vascular response, Cellular energy metabolism disorder, Oxidative stress and inflammation, Ion channels and membrane potential changes | Metabolic reprogramming, Tissue fibrosis and structural remodeling, Red blood cells and blood system adaptation, Angiogenesis and remodeling |

| Research Focus | Rapid start mechanism for injury, emergency intervention | Regulation of adaptive mechanisms, long-term health management |

| References | [25,26,27,28] | [4,4,29,30,31] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Dou, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Jiao, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, H. High-Altitude Hypoxia Injury: Systemic Mechanisms and Intervention Strategies on Immune and Inflammatory Responses. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010036

Zhang J, Guo S, Dou B, Liu Y, Wang X, Jiao Y, Li Q, Li Y, Chen H. High-Altitude Hypoxia Injury: Systemic Mechanisms and Intervention Strategies on Immune and Inflammatory Responses. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jingman, Shujie Guo, Beiebei Dou, Yang Liu, Xiaonan Wang, Yingze Jiao, Qianwen Li, Yan Li, and Han Chen. 2026. "High-Altitude Hypoxia Injury: Systemic Mechanisms and Intervention Strategies on Immune and Inflammatory Responses" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010036

APA StyleZhang, J., Guo, S., Dou, B., Liu, Y., Wang, X., Jiao, Y., Li, Q., Li, Y., & Chen, H. (2026). High-Altitude Hypoxia Injury: Systemic Mechanisms and Intervention Strategies on Immune and Inflammatory Responses. Antioxidants, 15(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010036