Bioenergetic Signatures of DLD Deficiency: Dissecting PDHc- and α-KGDHc-Linked Defects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Structural Modeling of DLD Variants

2.3. High-Resolution Respirometry

2.4. Approach for Discriminating PDHc- Versus αKGDHc-Linked Respiratory Pathways

2.5. DLD Enzymatic Activity Assay

2.6. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) Copy Number

2.7. Flow Cytometry Analysis of Mitochondrial Content

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

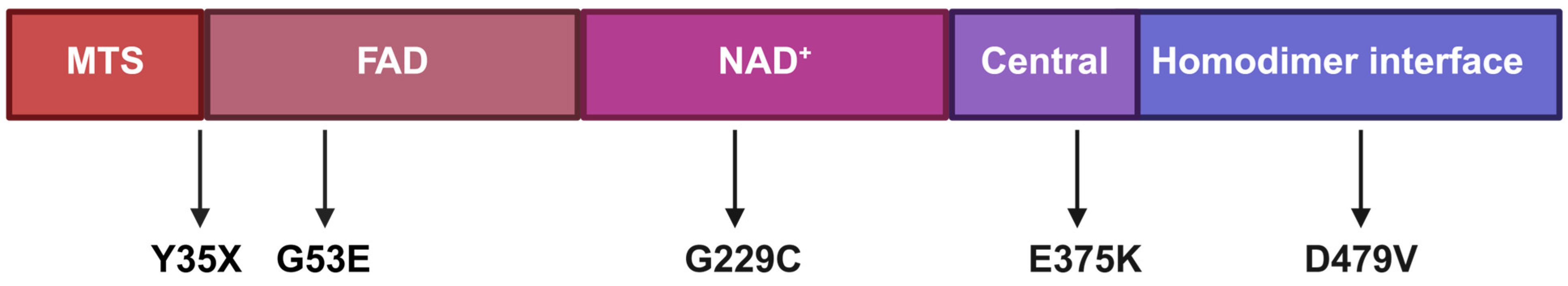

3.1. Patient Cohort

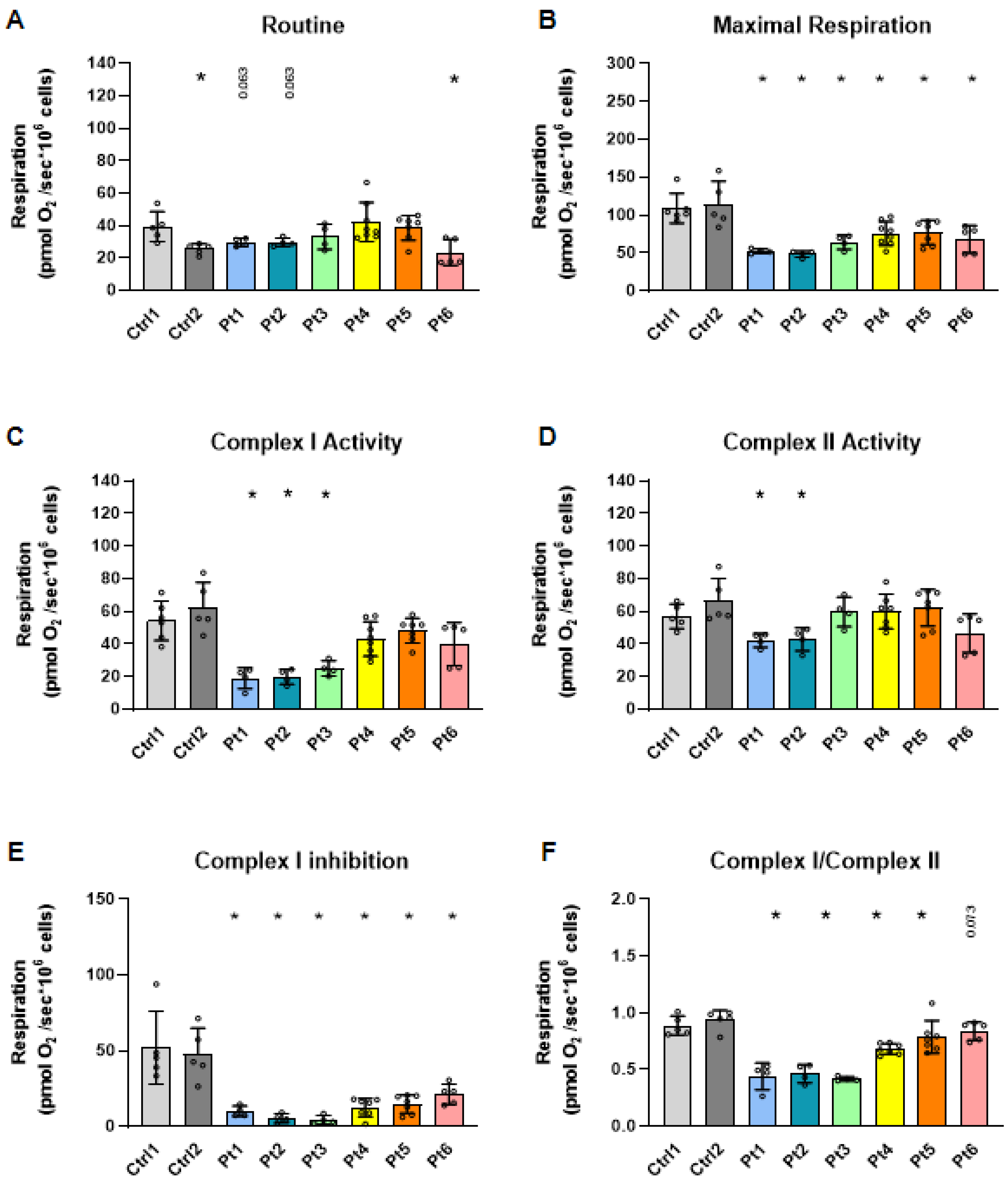

3.2. Mitochondrial Respiration in Patient-Derived Fibroblasts

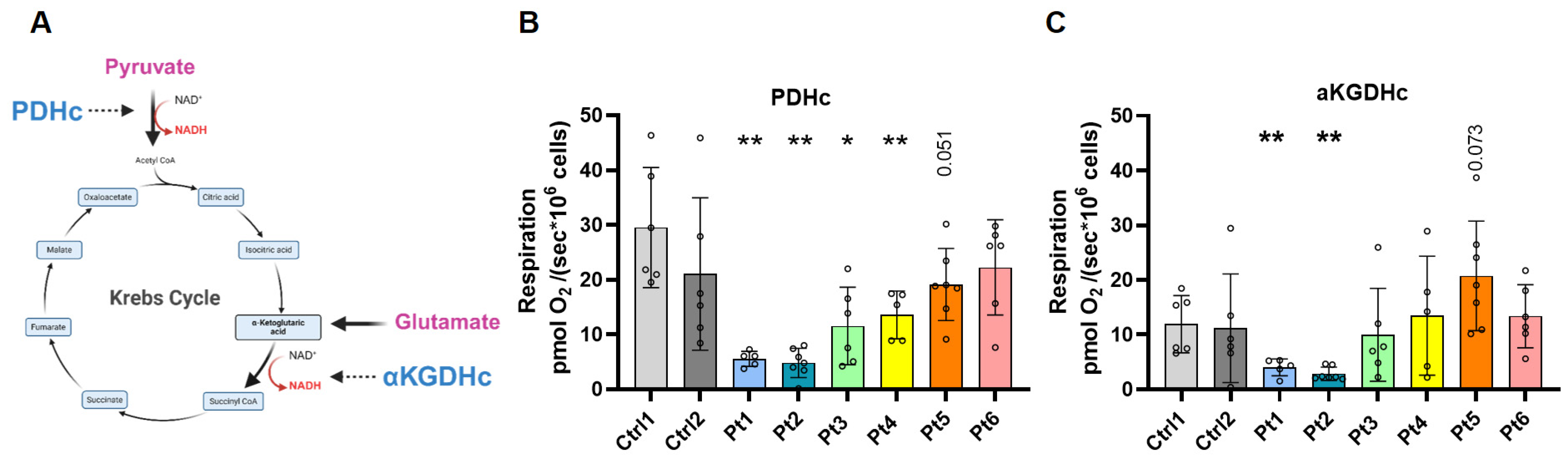

3.3. Distinguishing PDHc- and αKGDHc-Linked Respiration

3.4. Mitochondrial Mass Assessment

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DLD | Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase |

| PDHc | Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex |

| αKGDHc | α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex |

| BCKDHc | Branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase complex |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| FAD | Flavin adenine dinucleotide |

| NAD | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| SUIT | Substrate–uncoupler–inhibitor titration |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| ADP | Adenosine diphosphate |

| FCCP | Carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone |

| ETS | Electron transport system |

| nDNA | Nuclear DNA |

| CT | Cycle threshold |

| MTG | MitoTracker Green |

| FACS | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting |

| gMFI | Geometric mean fluorescence intensity |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| MTS | Mitochondrial targeting sequence |

| Ctrl | Control |

| PICU | Pediatric Intensive Care Unit |

| P | Protein |

| Pt | Patient |

| P/w | Presented with |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| DQ | Developmental quotient |

| iPSC | Induced pluripotent stem cell |

References

- Robinson, B.H.; Taylor, J.; Sherwood, W.G. Deficiency of Dihydrolipoyl Dehydrogenase (a Component of the Pyruvate and α-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase Complexes): A Cause of Congenital Chronic Lactic Acidosis in Infancy. Pediatr. Res. 1977, 11, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.S.; Roche, T.E. Molecular Biology and Biochemistry of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complexes. FASEB J. 1990, 4, 3224–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaag, A.; Saada, A.; Berger, I.; Mandel, H.; Joseph, A.; Feigenbaum, A.; Elpeleg, O.N. Molecular Basis of Lipoamide Dehydrogenase Deficiency in Ashkenazi Jews. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999, 82, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, J.M.; Levandovskiy, V.; MacKay, N.; Raiman, J.; Renaud, D.L.; Clarke, J.T.R.; Feigenbaum, A.; Elpeleg, O.; Robinson, B.H. Novel Mutations in Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase Deficiency in Two Cousins with Borderline-normal PDH Complex Activity. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2006, 140A, 1542–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brautigam, C.A.; Chuang, J.L.; Tomchick, D.R.; Machius, M.; Chuang, D.T. Crystal Structure of Human Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase: NAD+/NADH Binding and the Structural Basis of Disease-Causing Mutations. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 350, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.J.; Hackert, M.L. Structure-Function Relationships in Dihydrolipoamide Acyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 8971–8974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrus, A.; Torocsik, B.; Tretter, L.; Ozohanics, O.; Adam-Vizi, V. Stimulation of Reactive Oxygen Species Generation by Disease-Causing Mutations of Lipoamide Dehydrogenase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 2984–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunik, V.I.; Degtyarev, D. Structure–Function Relationships in the 2-oxo Acid Dehydrogenase Family: Substrate-specific Signatures and Functional Predictions for the 2-oxoglutarate Dehydrogenase-like Proteins. Proteins 2008, 71, 874–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shany, E.; Saada, A.; Landau, D.; Shaag, A.; Hershkovitz, E.; Elpeleg, O.N. Lipoamide Dehydrogenase Deficiency Due to a Novel Mutation in the Interface Domain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 262, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saada, A.; Aptowitzer, I.; Link, G.; Elpeleg, O.N. ATP Synthesis in Lipoamide Dehydrogenase Deficiency. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 269, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprecher, U.; Dsouza, J.; Marisat, M.; Barasch, D.; Mishra, K.; Kakhlon, O.; Manor, J.; Anikster, Y.; Weil, M. In Depth Profiling of Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase Deficiency in Primary Patients Fibroblasts Reveals Metabolic Reprogramming Secondary to Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2025, 42, 101172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, M.J.; Sheng, F.; Saada, A. Biochemical Assays of TCA Cycle and β-Oxidation Metabolites. Methods Cell Biol. 2020, 155, 83–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.; Ng, C.P.; Jones, O.; Fung, T.S.; Ryu, K.W.; Li, D.; Thompson, C.B. Lactate Activates the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain Independently of Its Metabolism. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 3904–3920.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawid, C.; Weber, D.; Musiol, E.; Janas, V.; Baur, S.; Lang, R.; Fromme, T. Comparative Assessment of Purified Saponins as Permeabilization Agents during Respirometry. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 2020, 1861, 148251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, J.P.; Ryde, I.T.; Sanders, L.H.; Howlett, E.H.; Colton, M.D.; Germ, K.E.; Mayer, G.D.; Greenamyre, J.T.; Meyer, J.N. PCR Based Determination of Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number in Multiple Species. In Mitochondrial Regulation; Palmeira, C.M., Rolo, A.P., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 1241, pp. 23–38. ISBN 978-1-4939-1874-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pode-Shakked, B.; Landau, Y.E.; Shaul Lotan, N.; Manor, J.; Haham, N.; Kristal, E.; Hershkovitz, E.; Hazan, G.; Haham, Y.; Almashanu, S.; et al. The Natural History of Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase Deficiency in Israel. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2024, 47, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammann, N.; Staufner, C.; Schlieben, L.D.; Dezsőfi-Gottl, A.; Feichtinger, R.G.; Häberle, J.; Junge, N.; Konstantopoulou, V.; Kopajtich, R.; McLin, V.; et al. Hepatic Form of Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase Deficiency (DLDD): Phenotypic Spectrum, Laboratory Findings, and Therapeutic Approaches in 52 Patients. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2025, 48, e70035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkittichote, P.; Cuddapah, S.R.; Master, S.R.; Grange, D.K.; Dietzen, D.; Roper, S.M.; Ganetzky, R.D. Biochemical Characterization of Patients with Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase Deficiency. JIMD Rep. 2023, 64, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrus, A.; Adam-Vizi, V. Human Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase (E3) Deficiency: Novel Insights into the Structural Basis and Molecular Pathomechanism. Neurochem. Int. 2018, 117, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgin, H.J.; McKenzie, M. Understanding the Role of OXPHOS Dysfunction in the Pathogenesis of ECHS1 Deficiency. FEBS Lett. 2020, 594, 590–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.C.; Tajika, M.; Shimura, M.; Carey, K.T.; Stroud, D.A.; Murayama, K.; Ohtake, A.; McKenzie, M. Loss of the Mitochondrial Fatty Acid β-Oxidation Protein Medium-Chain Acyl-Coenzyme A Dehydrogenase Disrupts Oxidative Phosphorylation Protein Complex Stability and Function. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustin, P.; Bourgeron, T.; Parfait, B.; Chretien, D.; Munnich, A.; Rötig, A. Inborn Errors of the Krebs Cycle: A Group of Unusual Mitochondrial Diseases in Human. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Basis Dis. 1997, 1361, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meirleir, L.J.; Van Coster, R.; Lissens, W. Disorders of Pyruvate Metabolism and the Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle. In Inborn Metabolic Diseases; Fernandes, J., Saudubray, J.-M., Van Den Berghe, G., Walter, J.H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 161–174. ISBN 978-3-540-28783-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gardeitchik, T.; Mohamed, M.; Ruzzenente, B.; Karall, D.; Guerrero-Castillo, S.; Dalloyaux, D.; van den Brand, M.; van Kraaij, S.; van Asbeck, E.; Assouline, Z.; et al. Bi-Allelic Mutations in the Mitochondrial Ribosomal Protein MRPS2 Cause Sensorineural Hearing Loss, Hypoglycemia, and Multiple OXPHOS Complex Deficiencies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 102, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antolínez-Fernández, Á.; Esteban-Ramos, P.; Fernández-Moreno, M.Á.; Clemente, P. Molecular Pathways in Mitochondrial Disorders Due to a Defective Mitochondrial Protein Synthesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1410245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaljević, M.; Petković Ramadža, D.; Žigman, T.; Rako, I.; Galić, S.; Matić, T.; Rubić, F.; Čulo Čagalj, I.; Mayer, D.; Gojević, A.; et al. Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase Deficiency in Five Siblings with Variable Phenotypes, Including Fulminant Fatal Liver Failure despite Good Engraftment of Transplanted Liver. JIMD Rep. 2024, 65, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.R.; Liu, K.; Yin, Z.; Liu, R.; Xia, Y.; Tan, L.; Yang, P.; Lee, J.-H.; Li, X.; et al. KAT2A Coupled with the α-KGDH Complex Acts as a Histone H3 Succinyltransferase. Nature 2017, 552, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shangguan, Y.; Tang, D.; Dai, Y. Histone Succinylation and Its Function on the Nucleosome. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 7101–7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, T.; Langer, T. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Metabolic Regulation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 27, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickles, S.; Vigié, P.; Youle, R.J. Mitophagy and Quality Control Mechanisms in Mitochondrial Maintenance. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, R170–R185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distelmaier, F.; Koopman, W.J.H.; van den Heuvel, L.P.; Rodenburg, R.J.; Mayatepek, E.; Willems, P.H.G.M.; Smeitink, J.A.M. Mitochondrial Complex I Deficiency: From Organelle Dysfunction to Clinical Disease. Brain 2009, 132, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koene, S.; Rodenburg, R.J.; van der Knaap, M.S.; Willemsen, M.A.A.P.; Sperl, W.; Laugel, V.; Ostergaard, E.; Tarnopolsky, M.; Martin, M.A.; Nesbitt, V.; et al. Natural Disease Course and Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in Complex I Deficiency Caused by Nuclear Gene Defects: What We Learned from 130 Cases. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2012, 35, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schon, E.A.; Przedborski, S. Mitochondria: The next (Neurode)Generation. Neuron 2011, 70, 1033–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, Y.; Seldin, M.; Lusis, A. Multi-Omics Approaches to Disease. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avior, Y.; Sagi, I.; Benvenisty, N. Pluripotent Stem Cells in Disease Modelling and Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiduschka, S.; Prigione, A. iPSC Models of Mitochondrial Diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 2025, 207, 106822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radenkovic, S.; Budhraja, R.; Klein-Gunnewiek, T.; King, A.T.; Bhatia, T.N.; Ligezka, A.N.; Driesen, K.; Shah, R.; Ghesquière, B.; Pandey, A.; et al. Neural and Metabolic Dysregulation in PMM2-Deficient Human in Vitro Neural Models. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pt | Gender and Ethnicity | DLD Genotype (P) | Onset | Clinical Presentation | MRI | EEG | Development | Treatment | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt1 | M, Bedouin | D479V/ D479V | 1 day | P/w severe lactic acidosis. Later developed recurrent crises of lactic acidosis and hypoglycemia (mostly triggered by infections). Developed seizures, spasticity, and failure to thrive. | N/A | Hypsarrhythmia | Severe global developmental delay with minimal attained milestones. | Sodium bicarbonate, anti-epileptics (Keppra, clonazepam), vitamin D, potassium citrate. Modified ketogenic diet (1:0.82). | Normalization of EEG. |

| Pt2 | F, Bedouin | D479V/ D479V | At birth | P/w severe lactic acidosis (pH 6.9). Later developed recurrent crises of lactic acidosis (mostly triggered by infections). Developed seizures, spasticity, failure to thrive and osteopenia. | Basal nuclei hyperintensity, cerebral ventriculomegaly. | Epileptiformic discharges (right temporal and frontal). | Severe global developmental delay with minimal attained milestones. | Sodium bicarbonate, anti-epileptics (Keppra), vitamin D, bisphosphonates (IV), and potassium citrate. Modified ketogenic diet (1:0.76). | Normalization of EEG. |

| Pt3 | M, Ashkenazi Jewish | E375K/ E375K | 3 months | P/w lactic acidosis and elevated liver enzymes, followed by intermittent crises until age 5 with lactic acidosis, hypoglycemia, vomiting and elevated liver enzymes. | N/A | N/A | Primarily motor developmental delay. Mild dysarthria and dystonia. | Carnitine, sodium bicarbonate, Thiamine, vitamin D, muscle relaxants, and potassium citrate. Modified ketogenic diet (1:0.6). | Crises free > 7 years. |

| Pt4 | M, Ashkenazi Jewish | Y35X/ G229C | 1 year | Recurrent crises of lactic acidosis, hypoglycemia, vomiting, elevated liver enzymes, hyperammonemia. | N/A | N/A | Motor developmental delay, hypotonia, scoliosis. | Riboflavin and Vitamin complex B. Received DCA which was discontinued due to concerns of neuropathy. | Crisis free > 10 years. |

| Pt5 | M, Mixed AshkenaziSephardic Jewish | G53E/ G229C | 12 h | P/w lactic acidosis, hypoglycemia and hypotonia, followed by intermittent crises of lactic acidosis, hypoglycemia, vomiting, elevated liver enzymes, hyperammonemia, and hypotonia. | Gliotic-cystic changes bilaterally in the basal ganglia, diffusion restriction bilateral foci in the globus pallidus. | Normal | Speech and motor delays, limb dystonia. | Riboflavin, tetrabenazine, risperidone. Diet: minimize carbohydrates from table food. | Improved appetite and weight gain. Improvement of focal lesions (MRI). Multiple admission for crises involving confusion and worsening of movement disorders. |

| Pt6 | M, Mixed Ashkenazi, Northern African Jewish | G229C/ G229C | 3 days | P/w severe hypoglycemia and seizures associated with hyperammonemia. Recurrent crises of hypoglycemia, seizures, vomiting, elevated liver enzymes, hyperammonemia and encephalopathy. | Global brain atrophy. | Multifocal epileptic activity with generalized slowing. | Global developmental delay. Intellectual disability (DQ 40). | Carnitine, riboflavin, anti-epileptics and vitamin B6. Full ketogenic diet. | No metabolic crises, and persistent developmental improvement. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Haham Zarbib, Y.; Huri Ohev-Shalom, S.; Lyskov, S.K.; Mazor, Y.; Anekstein-Spigel, M.; Shalva, N.; Spiegel, R.; Staretz-Chacham, O.; Manor, J.; Saada, A.; et al. Bioenergetic Signatures of DLD Deficiency: Dissecting PDHc- and α-KGDHc-Linked Defects. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010019

Haham Zarbib Y, Huri Ohev-Shalom S, Lyskov SK, Mazor Y, Anekstein-Spigel M, Shalva N, Spiegel R, Staretz-Chacham O, Manor J, Saada A, et al. Bioenergetic Signatures of DLD Deficiency: Dissecting PDHc- and α-KGDHc-Linked Defects. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaham Zarbib, Yarden, Shira Huri Ohev-Shalom, Shani Kassia Lyskov, Yuval Mazor, Mika Anekstein-Spigel, Nechama Shalva, Ronen Spiegel, Orna Staretz-Chacham, Joshua Manor, Ann Saada, and et al. 2026. "Bioenergetic Signatures of DLD Deficiency: Dissecting PDHc- and α-KGDHc-Linked Defects" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010019

APA StyleHaham Zarbib, Y., Huri Ohev-Shalom, S., Lyskov, S. K., Mazor, Y., Anekstein-Spigel, M., Shalva, N., Spiegel, R., Staretz-Chacham, O., Manor, J., Saada, A., Rock, R., Anikster, Y., & Yardeni, T. (2026). Bioenergetic Signatures of DLD Deficiency: Dissecting PDHc- and α-KGDHc-Linked Defects. Antioxidants, 15(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010019