BiombalanceTM: A Specific Oligomeric Procyanidin-Rich Grape Seed Extract as Multifunctional Ingredient Integrating Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities with Beneficial Gut–Brain Axis Modulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

2.2. Bacterial Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

2.2.1. Bacterial Minimum Inhibitory Concentration in Aerobic Conditions

2.2.2. Bacterial Minimum Inhibitory Concentration in Anaerobic Conditions

2.2.3. Bacterial Minimum Inhibitory Concentration Microaerophilic Conditions

2.3. Caco-2 Cells Culture

2.4. Study of the Antioxidant Effect of BB in Caco-2 Cells

2.5. Study of the Anti-Inflammatory Effect of BB in Caco-2 Cells

2.6. Quantification of Gene Expression in Caco-2 by qRT-PCR

2.7. Animal Experiment Design

2.8. Tissue Sampling, RNA Extraction, and Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR)

2.9. Stool Sampling, Faecal DNA Extraction, and 16S rDNA Sequencing

2.10. PCR and Microbiota Analysis

2.11. PICRUS (Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States) Analysis

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Antibacterial Effects of BB

3.2. Antioxidant Effect of BB In Vitro

3.3. BB Extract Alleviates Inflammation Markers

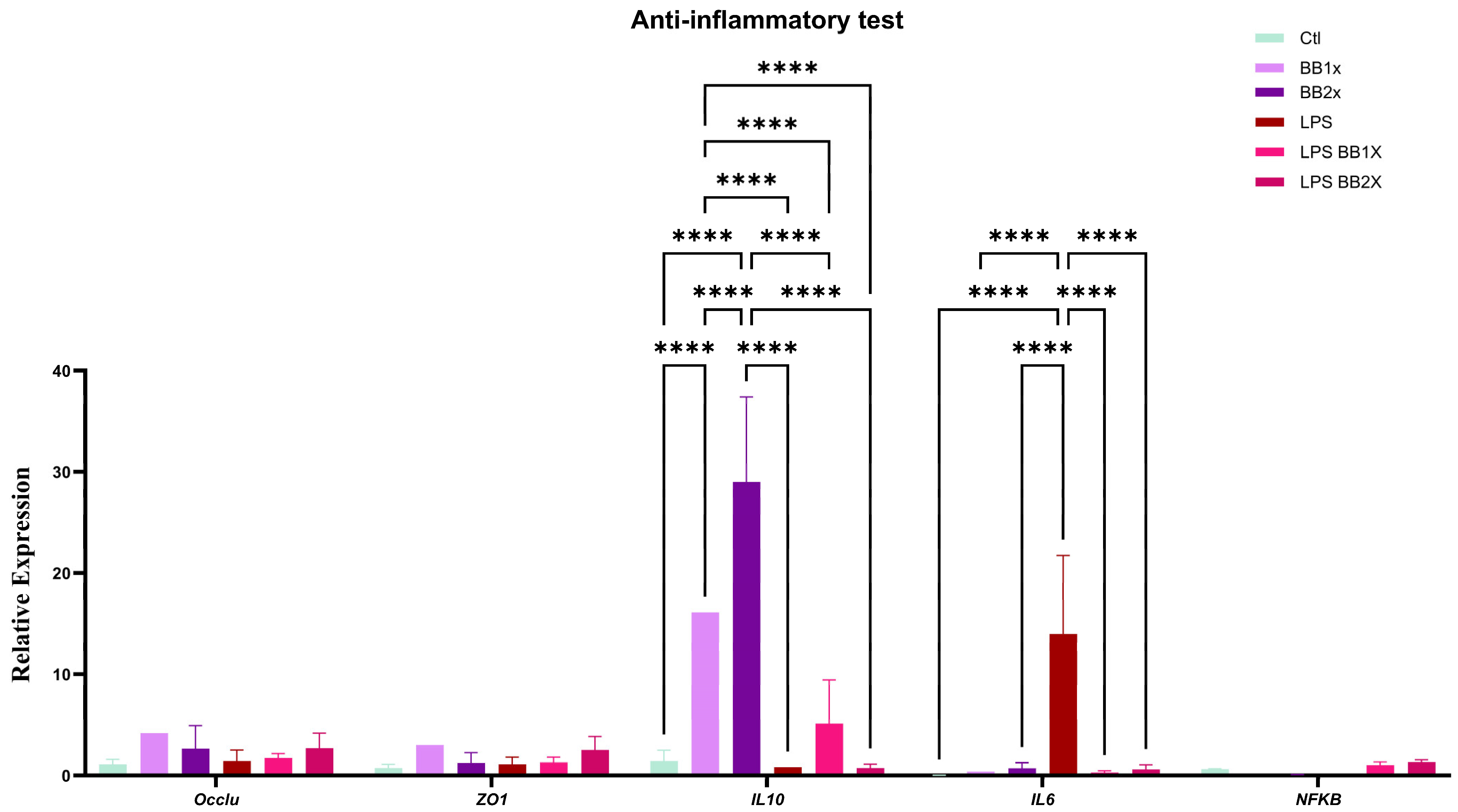

3.4. BB Extract Modulates Colon Gene Expression in Murine Model

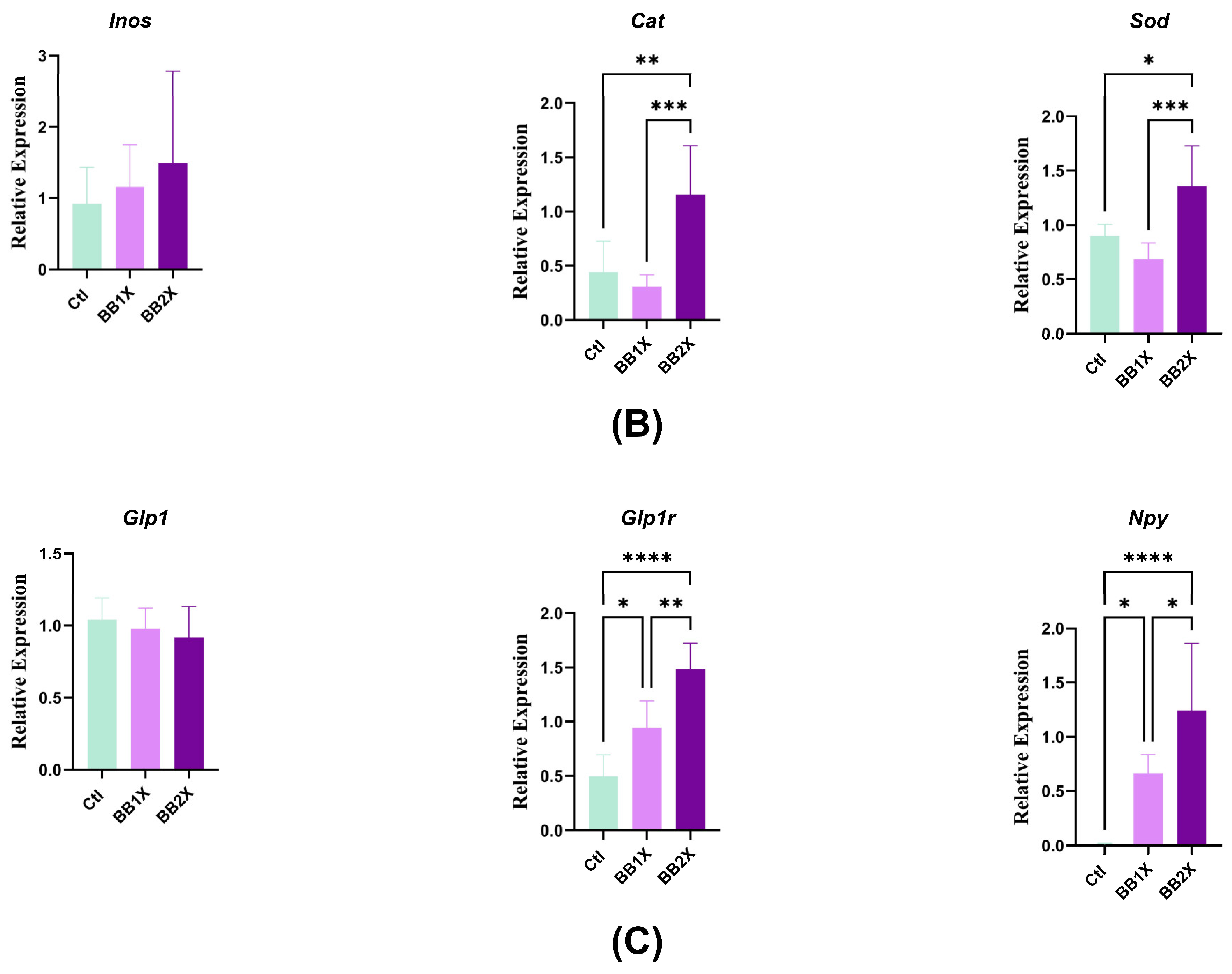

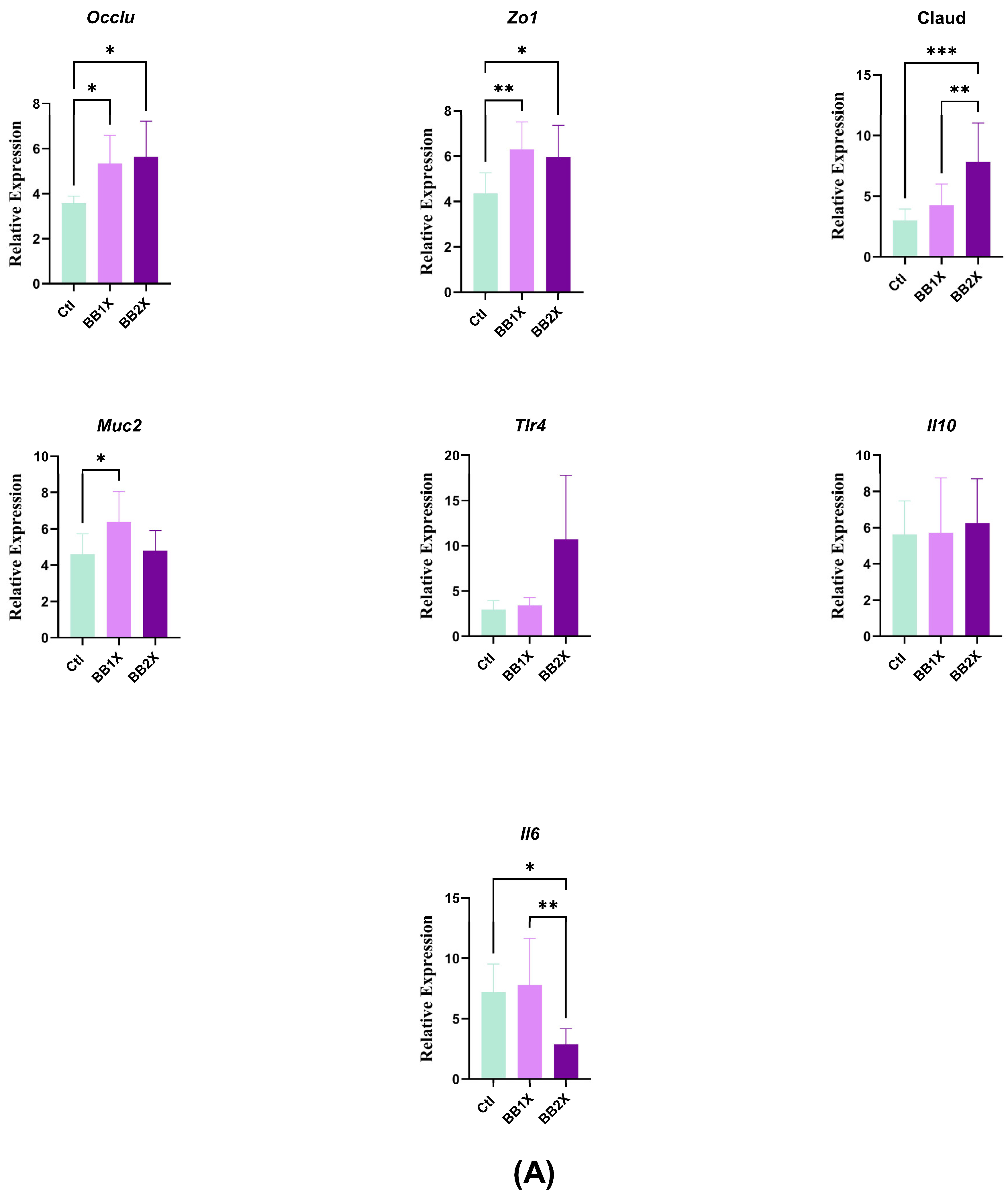

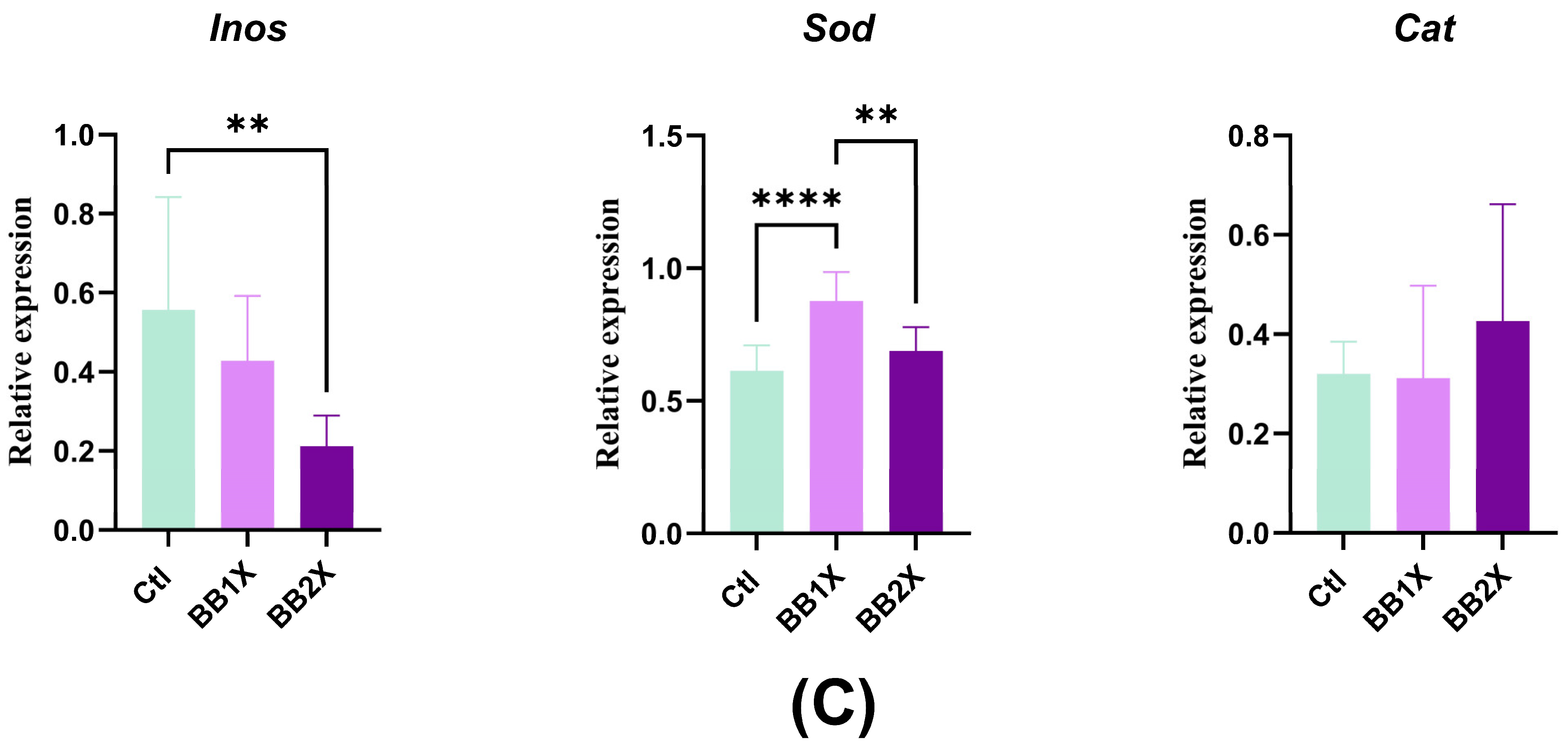

3.5. BiombalanceTM Modulates Ileal Gene Expression in Mice

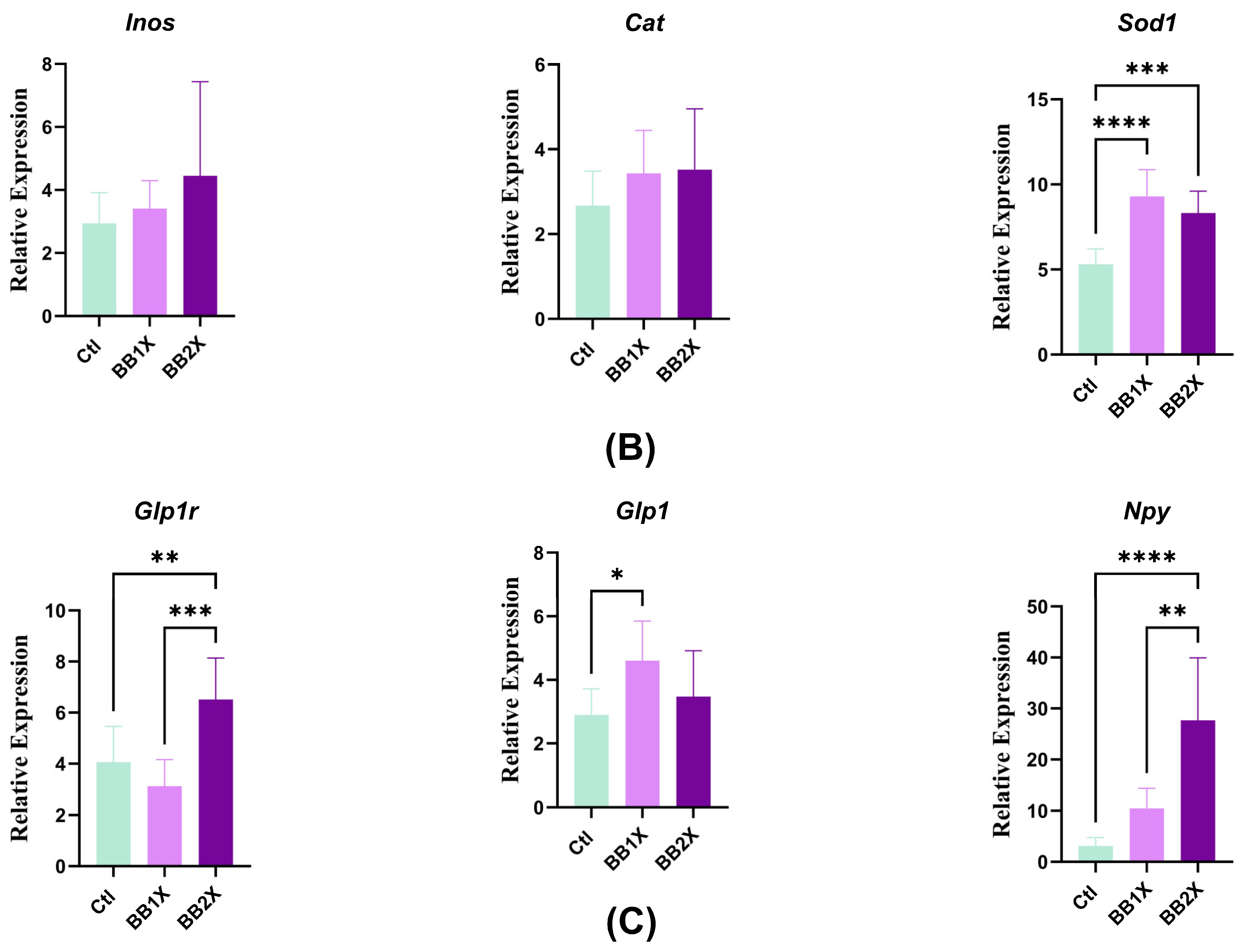

3.6. BB Extract Modulates Liver Gene Expression in Mice

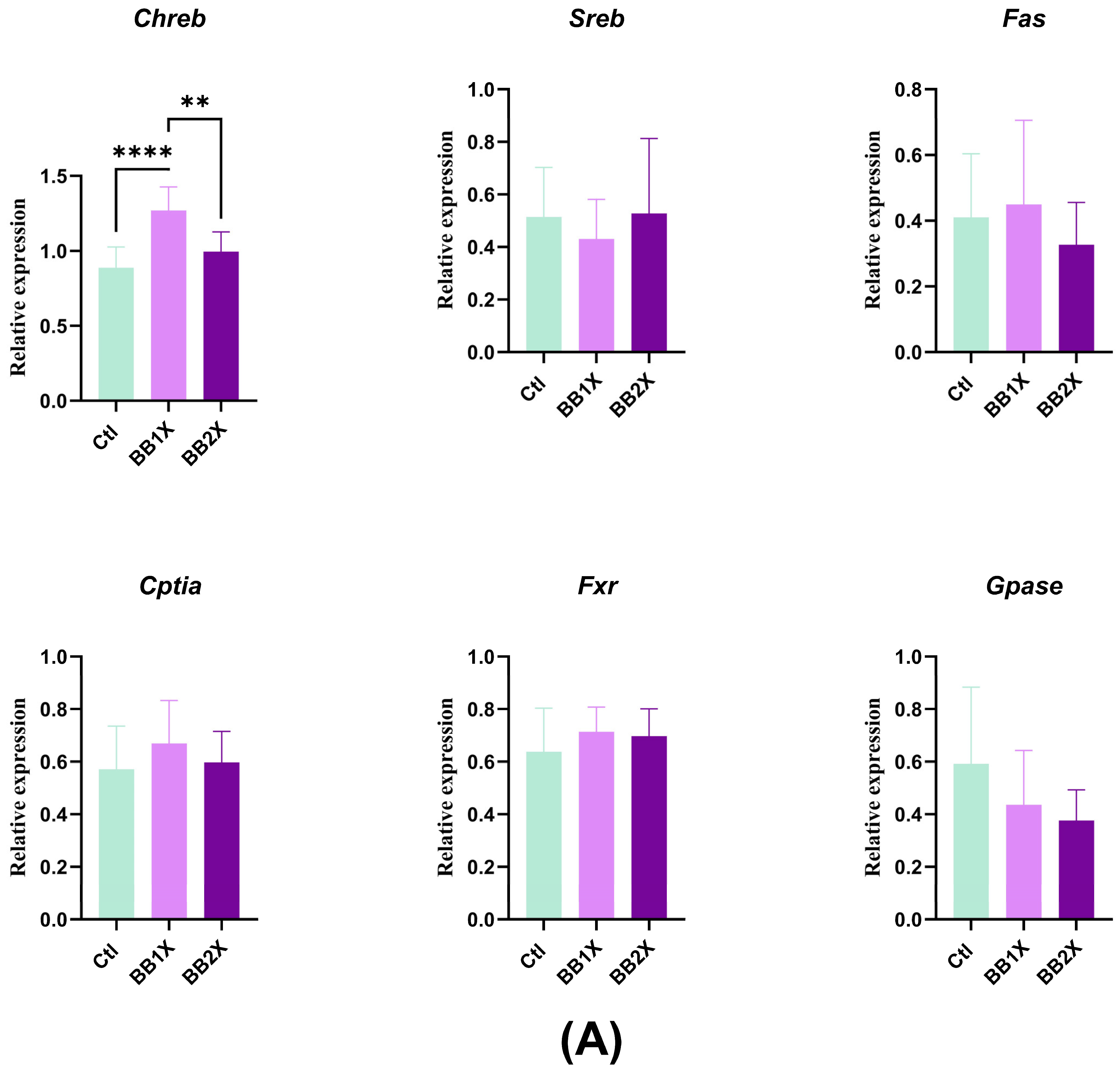

3.7. BB Extract Modulates the Gut Microbiota

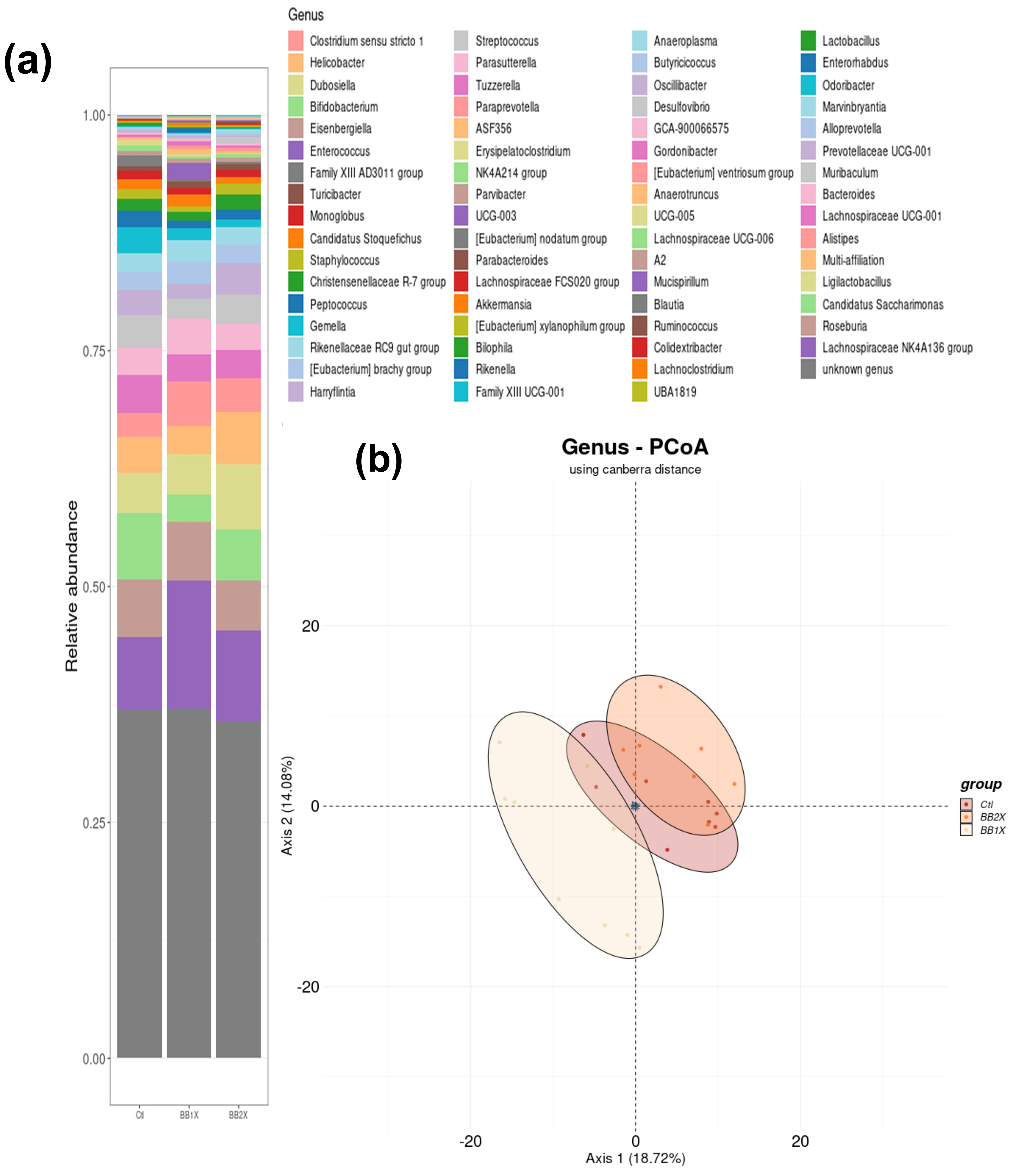

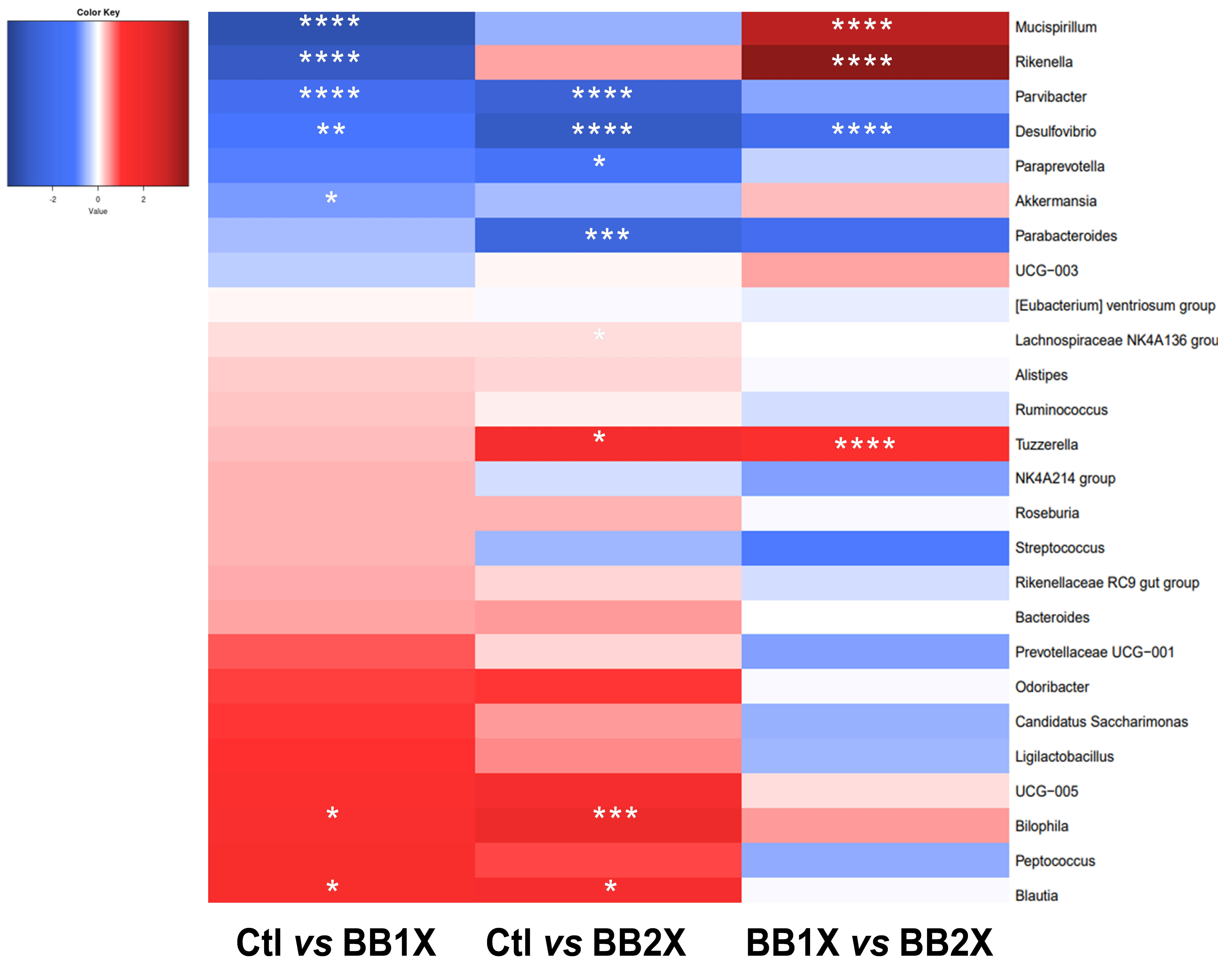

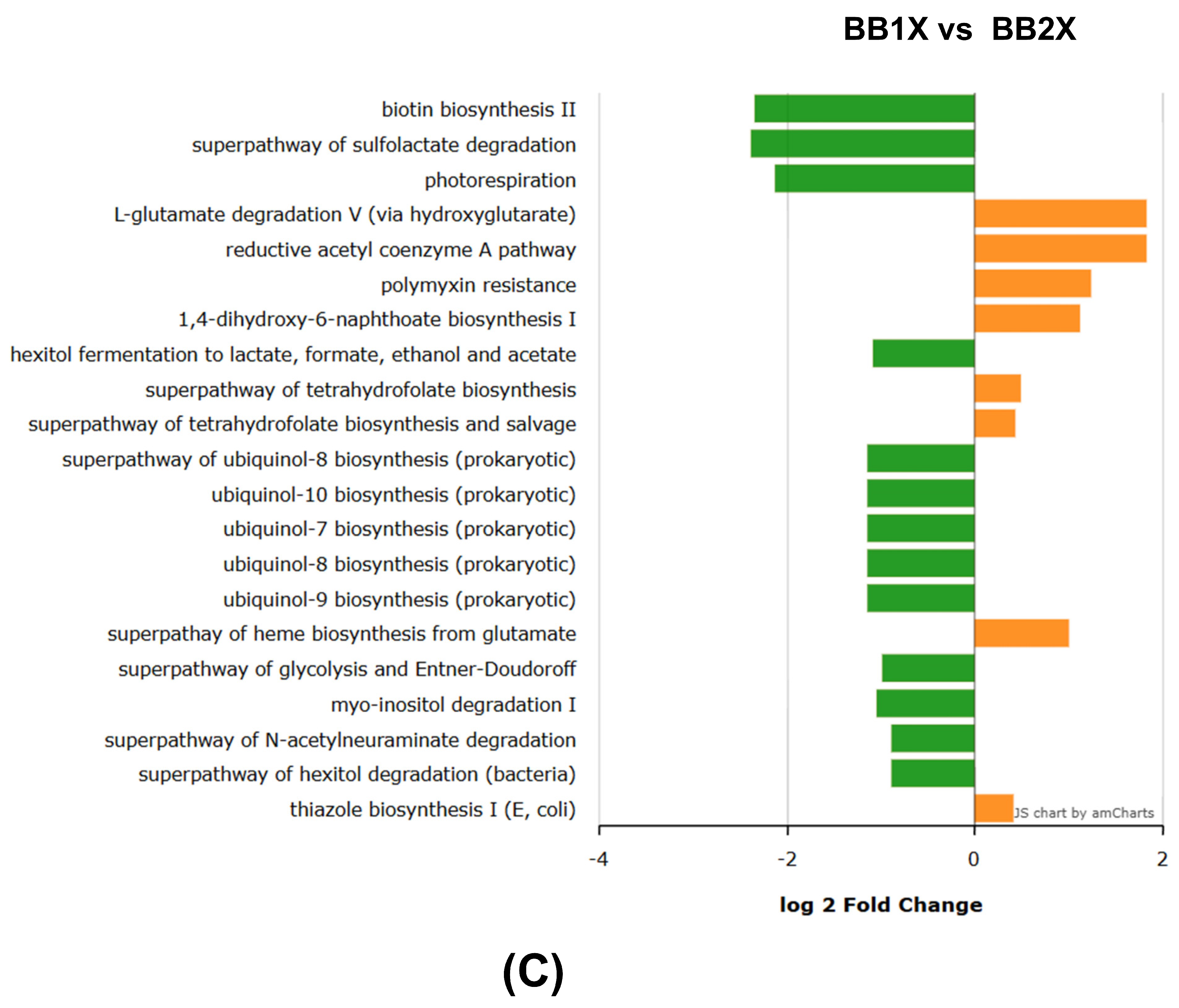

3.8. PICRUS Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARG-1 | arginase 1 |

| CAT | catalase |

| ChREBP | carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein |

| CLAUD | claudin |

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| FXR | Farnesoid X Receptor |

| GLP-1 | glucagon-Like Peptide-1 |

| GLP-1r | glucagon-Like Peptide-1 receptor |

| HPRT | hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase |

| IL-6 | interleukin 6 |

| IL-10 | interleukin 10 |

| iNOS | inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| MUC2 | mucin 2 |

| NOD-1 | nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain-containing protein 1 |

| NOD-2 | nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain-containing protein 2 |

| NPY | neuropeptide Y |

| OCCLU | occludin |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| TLR4 | toll-like receptor 4 |

| TNF-α | tumour necrosis factor α |

| ZO-1 | zonula occluens-1 |

References

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Rashmi, R.; Toppo, V.; Chole, P.B.; Banadka, A.; Sudheer, W.N.; Nagella, P.; Shehata, W.F.; Al-Mssallem, M.Q.; Alessa, F.M.; et al. Plant Secondary Metabolites: The Weapons for Biotic Stress Management. Metabolites 2023, 13, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratyusha, S.; Pratyusha, S. Phenolic Compounds in the Plant Development and Defense: An Overview. In Plant Stress Physiology—Perspectives in Agriculture; Hasanuzzaman, M., Nahar, K., Eds.; Intech: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.C.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S.; Giovinazzo, G.; Gerardi, C.; Mosca, L. Plant Flavonoids: Chemical Characteristics and Biological Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozier, A.; Jaganath, I.B.; Clifford, M.N. Dietary Phenolics: Chemistry, Bioavailability and Effects on Health. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009, 26, 1001–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosso, A.; Cassino, C.; Motta, S.; Panero, L.; Tsolakis, C.; Guaita, M. Polyphenolic Composition and In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Red Grape Seeds as Byproducts of Short and Medium-Long Fermentative Macerations. Foods 2020, 9, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadri, S.; El Ayed, M.; Cosette, P.; Jouenne, T.; Elkhaoui, S.; Zekri, S.; Limam, F.; Aouani, E.; Mokni, M. Neuroprotective Effect of Grape Seed Extract on Brain Ischemia: A Proteomic Approach. Metab. Brain Dis. 2019, 34, 889–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.P. Tannin Degradation by Phytopathogen’s Tannase: A Plant’s Defense Perspective. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 101342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Lamothe, R.; Mitchell, G.; Gattuso, M.; Diarra, M.S.; Malouin, F.; Bouarab, K. Plant Antimicrobial Agents and Their Effects on Plant and Human Pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daglia, M. Polyphenols as Antimicrobial Agents. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, J.; Caillet, S.; Doyon, G.; Sylvain, J.F.; Lacroix, M. Bioactive Compounds in Cranberries and Their Biological Properties. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.C.; Huang, G.; Haley-Zitlin, V.; Jiang, X. Antibacterial Effects of Grape Extracts on Helicobacter Pylori. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 75, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, M.; Nadora, D.; Chakkalakal, M.; Afzal, N.; Subramanyam, C.; Gahoonia, N.; Pan, A.; Thacker, S.; Nong, Y.; Chambers, C.J.; et al. An Oral Botanical Supplement Improves Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) and Facial Redness: Results of an Open-Label Clinical Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onofrio, G.; Scala, M.; Severino, M.; Roberti, R.; Romano, F.; De Marco, P.; Iacomino, M.; Baldassari, S.; Uva, P.; Pavanello, M.; et al. Expanding the Phenotype Associated with Biallelic SLC20A2 Variants. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 31, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vendrame, S.; Guglielmetti, S.; Riso, P.; Arioli, S.; Klimis-Zacas, D.; Porrini, M. Six-Week Consumption of a Wild Blueberry Powder Drink Increases Bifidobacteria in the Human Gut. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2011, 59, 12815–12820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabasco, R.; Sánchez-Patán, F.; Monagas, M.; Bartolomé, B.; Victoria Moreno-Arribas, M.; Peláez, C.; Requena, T. Effect of Grape Polyphenols on Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bifidobacteria Growth: Resistance and Metabolism. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellavite, P. Neuroprotective Potentials of Flavonoids: Experimental Studies and Mechanisms of Action. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattioli, R.; Francioso, A.; Mosca, L.; Silva, P. Anthocyanins: A Comprehensive Review of Their Chemical Properties and Health Effects on Cardiovascular and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2020, 25, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plamada, D.; Vodnar, D.C. Polyphenols—Gut Microbiota Interrelationship: A Transition to a New Generation of Prebiotics. Nutrients 2021, 14, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, K.; Ran, X.; Wang, W.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhang, T. Combination of Resveratrol and Luteolin Ameliorates α-Naphthylisothiocyanate-Induced Cholestasis by Regulating the Bile Acid Homeostasis and Suppressing Oxidative Stress. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 7098–7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerardi, G.; Cavia-Saiz, M.; Rivero-Pérez, M.D.; González-Sanjosé, M.L.; Muñiz, P. The Dose–Response Effect on Polyphenol Bioavailability after Intake of White and Red Wine Pomace Products by Wistar Rats. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 1661–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokrani, M.; Saad, N.; Nardy, L.; Sifré, E.; Despres, J.; Brochot, A.; Varon, C.; Urdaci, M.C. BiombalanceTM, an Oligomeric Procyanidins-Enriched Grape Seed Extract, Prevents Inflammation and Microbiota Dysbiosis in a Mice Colitis Model. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.Á.; Ramos, S. Impact of Cocoa Flavanols on Human Health. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 151, 112121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtois, S.; Bénéjat, L.; Izotte, J.; Mégraud, F.; Varon, C.; Lehours, P.; Bessède, E. Metformin Can Inhibit Helicobacter pylori Growth. Future Microbiol. 2018, 13, 1575–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, G.; Beloeil, P.; Fierro, R.G.; Guerra, B.; Rizzi, V.; Stoicescu, A. Manual for Reporting 2023 Antimicrobial Resistance Data under Directive 2003/99/EC and Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/1729. EFSA Support. Publ. 2024, 21, 8585E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 30th ed.; CLSI supplement M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Locati, M.; Curtale, G.; Mantovani, A. Diversity, Mechanisms, and Significance of Macrophage Plasticity. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2020, 15, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cilla, A.; Rodrigo, M.J.; Zacarías, L.; De Ancos, B.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Barberá, R.; Alegría, A. Protective Effect of Bioaccessible Fractions of Citrus Fruit Pulps against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress in Caco-2 Cells. Food Res. Int. 2018, 103, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carasi, P.; Racedo, S.M.; Jacquot, C.; Romanin, D.E.; Serradell, M.A.; Urdaci, M.C. Impact of Kefir Derived Lactobacillus kefiri on the Mucosal Immune Response and Gut Microbiota. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 361604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokrani, M.; Elie, A.M.; Jacquot, C.; Kiran, F.; Urdaci, M.C. Encapsulation of a Pediocin PA-1 Producer Pediococcus acidilactici and its Impact on Enhanced Survival and Gut Microbiota Modulation. Microb. Health Dis. 2024, 6, e996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokrani, M.; Charradi, K.; Limam, F.; Aouani, E.; Urdaci, M.C. Grape Seed and Skin Extract, a Potential Prebiotic with Anti-Obesity Effect through Gut Microbiota Modulation. Gut Pathog. 2022, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudié, F.; Auer, L.; Bernard, M.; Mariadassou, M.; Cauquil, L.; Vidal, K.; Maman, S.; Hernandez-Raquet, G.; Combes, S.; Pascal, G. FROGS: Find, Rapidly, OTUs with Galaxy Solution. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samb, M.; Bernard, M.; Pascal, G. Functional inference integrated in the FROGS suite. JOBIM2020 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Volant, S.; Lechat, P.; Woringer, P.; Motreff, L.; Campagne, P.; Malabat, C.; Kennedy, S.; Ghozlane, A. SHAMAN: A User-Friendly Website for Metataxonomic Analysis from Raw Reads to Statistical Analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2020, 21, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, G.M.; Maffei, V.J.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Yurgel, S.N.; Brown, J.R.; Taylor, C.M.; Huttenhower, C.; Langille, M.G.I. PICRUSt2 for Prediction of Metagenome Functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidi, S.; Fatima, N.; Mumtaz, T.; Farooq, S.; Naeem, H.; Tariq, M.; Mujahid, S.; Pharm, B.; Pharm, M. Exploring the Synergistic Antibacterial Potential of Grape Seed and Cranberry Fruit Extract Combination Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Popul. Ther. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 30, 2450–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguri, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kouno, I. Antibacterial Spectrum of Plant Polyphenols and Extracts Depending upon Hydroxyphenyl Structure. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2006, 29, 2226–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallon, C.M.; Smyth, J.S.; Quach, A.; Lajczak-McGinley, N.; O’Toole, A.; Barrett, K.E.; Sheridan, H.; Keely, S.J. Pentacyclic Triterpenes Modulate Farnesoid X Receptor Expression in Colonic Epithelial Cells: Implications for Colonic Secretory Function. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braeuning, A.; Mentz, A.; Schmidt, F.F.; Albaum, S.P.; Planatscher, H.; Kalinowski, J.; Joos, T.O.; Poetz, O.; Lichtenstein, D. RNA-Protein Correlation of Liver Toxicity Markers in HepaRG Cells. EXCLI J. 2020, 19, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukowicz, A.C.; Lacy, B.E.; Levine, G.M. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Comprehensive Review. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 3, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Husebye, E.; Skar, V.; Høverstad, T.; Melby, K. Fasting Hypochlorhydria with Gram Positive Gastric Flora Is Highly Prevalent in Healthy Old People. Gut 1992, 33, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yao, C.; Li, Y.; Luo, L.; Xie, F.; Xiong, Q.; Feng, P. Effect of Polyphenol Compounds on Helicobacter Pylori Eradication: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e062932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Cheon, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Shin, J.Y.; Kim, H.; Ryu, G.; Chung, I.Y.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Gut Microbial Production of Imidazole Propionate Drives Parkinson’s Pathologies. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkarimi, M.; Eskandarion, S.; Bargrizan, M.; Delazar, A.; Kharazifard, M.J. Remineralization of Artificial Caries in Primary Teeth by Grape Seed Extract: An In Vitro Study. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospects 2013, 7, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso, T.; Lores, M.; de Miguel, T. Antimicrobial Activity of Polyphenols and Natural Polyphenolic Extracts on Clinical Isolates. Antibiotics 2021, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowska, A.K.; Wilczak, A.; Skowrońska, W.; Michel, P.; Melzig, M.F.; Czerwińska, M.E. Fruits of Hippophaë Rhamnoides in Human Leukocytes and Caco-2 Cell Monolayer Models—A Question about Their Preventive Role in Lipopolysaccharide Leakage and Cytokine Secretion in Endotoxemia. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 981874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food Sources and Bioavailability 1,2. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 727–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraga, C.G.; Croft, K.D.; Kennedy, D.O.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. The Effects of Polyphenols and Other Bioactives on Human Health. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Qi, Y.; Zheng, H.; Wang, X.; Qi, Y.; Zheng, H. Dietary Polyphenol, Gut Microbiota, and Health Benefits. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Yu, X.; Novák, P.; Gui, Q.; Yin, K. Enhancing Intestinal Barrier Efficiency: A Novel Metabolic Diseases Therapy. Front Nutr. 2023, 10, 1120168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Tuo, X.; Wang, L.; Tundis, R.; Portillo, M.P.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Yu, Y.; Zou, L.; Xiao, J.; Deng, J. Bioactive Procyanidins from Dietary Sources: The Relationship between Bioactivity and Polymerization Degree. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yu, J.; Pohorly, J.E.; Kakuda, Y. Polyphenolics in Grape Seeds-Biochemistry and Functionality. J. Med. Food 2003, 6, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.Y.; Chen, W.C.; Shi, Y.C.; Wang, C.M.; Lin, S.; He, H.F. Regulation of Neuropeptide Y in Body Microenvironments and Its Potential Application in Therapies: A Review. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornhuber, J.; Zoicas, I. Neuropeptide Y Prolongs Non-Social Memory and Differentially Affects Acquisition, Consolidation, and Retrieval of Non-Social and Social Memory in Male Mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamamah, S.; Covasa, M. Gut Microbiota Restores Central Neuropeptide Deficits in Germ-Free Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, M.K.; Lee, J.W.; Woo, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.H.; Choi, J.H. Regulation of Colonic Neuropeptide Y Expression by the Gut Microbiome in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis and Its Association with Anxiety- and Depression-like Behavior in Mice. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2319844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor: Mechanisms and Advances in Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marathe, C.S.; Rayner, C.K.; Jones, K.L.; Horowitz, M. Effects of GLP-1 and Incretin-Based Therapies on Gastrointestinal Motor Function. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2011, 2011, 279530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Geng, W. Kombucha Reduces Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes of Mice by Regulating Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolites. Foods 2022, 11, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartinah, N.T.; Fadilah, F.; Ibrahim, E.I.; Suryati, Y. The Potential of Hibiscus Sabdariffa Linn in Inducing Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 via SGLT-1 and GLPR in DM Rats. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 8724824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlebowicz, J.; Hlebowicz, A.; Lindstedt, S.; Björgell, O.; Höglund, P.; Hoist, J.J.; Darwiche, G.; Almér, L.O. Effects of 1 and 3 g Cinnamon on Gastric Emptying, Satiety, and Postprandial Blood Glucose, Insulin, Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide, Glucagon-like Peptide 1, and Ghrelin Concentrations in Healthy Subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, J.J.; Andersen, D.B.; Grunddal, K.V. Actions of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Ligands in the Gut. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusta, B.; Matthews, D.; Flock, G.B.; Ussher, J.R.; Lavoie, B.; Mawe, G.M.; Drucker, D.J. Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Promotes Gallbladder Refilling via a TGR5-Independent, GLP-2R-Dependent Pathway. Mol. Metab. 2017, 6, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Wu, N.; Ren, S.; Wang, X.; Mu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Yu, W.; Guo, J. Profiling Blautia at High Taxonomic Resolution Reveals Correlations with Cognitive Dysfunction in Chinese Children with Down Syndrome. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1109889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Liu, X.; Jiang, R.; Yan, X.; Ling, Z. Roles and Mechanisms of Gut Microbiota in Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 650047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Sheng, L.; Zhong, J.; Tao, X.; Zhu, W.; Ma, J.; Yan, J.; Zhao, A.; Zheng, X.; Wu, G.; et al. Desulfovibrio vulgaris, a Potent Acetic Acid-Producing Bacterium, Attenuates Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1930874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinert, R.E.; Rehman, A.; Sadabad, M.S.; Milanese, A.; Wittwer-Schegg, J.; Burton, J.P.; Spooren, A. Microbial Micronutrient Sharing, Gut Redox Balance and Keystone Taxa as a Basis for a New Perspective to Solutions Targeting Health from the Gut. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2477816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñuela-Berni, V.; Carbajo-Mata, M.A.; Corona, R.; Morales, T. Gavage versus Dietary Adenine Administration Is More Effective for the Female Mouse Model of Chronic Kidney Disease. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen-Blevins, C.R.; You, X.; Hinde, K.; Sela, D.A. Handling Stress May Confound Murine Gut Microbiota Studies. PeerJ 2017, 2017, e2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaway, D.; Haydock, R.; Lonsdale, Z.N.; Deusch, O.D.; O’Flynn, C.; Hughes, K.R. Rapid Reconstitution of the Fecal Microbiome after Extended Diet-Induced Changes Indicates a Stable Gut Microbiome in Healthy Adult Dogs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00562-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, J.P.; Flannigan, K.L.; Agbor, T.A.; Beatty, J.K.; Blackler, R.W.; Workentine, M.L.; Da Silva, G.J.; Wang, R.; Buret, A.G.; Wallace, J.L. Hydrogen Sulfide Protects from Colitis and Restores Intestinal Microbiota Biofilm and Mucus Production. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosnan, J.T. Glutamate, at the Interface between Amino Acid and Carbohydrate Metabolism. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 988S–990S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltais-Payette, I.; Tchernof, A. Circulating Glutamate as a Potential Biomarker of Central Fat Accumulation and Concomitant Cardiometabolic Alterations. In Biomarkers in Nutrition; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 955–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Guasch-Ferré, M.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Toledo, E.; Clish, C.; Liang, L.; Razquin, C.; Corella, D.; Estruch, R.; et al. High Plasma Glutamate and Low Glutamine-to-Glutamate Ratio Are Associated with Type 2 Diabetes: Case-Cohort Study within the PREDIMED Trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019, 29, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zhao, L.; Hu, Q.; Hung, I.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Mei, X.; Zeng, X.; Bin, P.; Wang, J. Gut Microbiota-Mediated Modulation of Host Amino Acid Availability and Metabolism. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2552345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; van Meel, E.R.; Medina-Gomez, C.; Kraaij, R.; Barroso, M.; Kiefte-de Jong, J.; Radjabzadeh, D.; Pasmans, S.G.M.A.; de Jong, N.W.; de Jongste, J.C.; et al. A Population-Based Study on Associations of Stool Microbiota with Atopic Diseases in School-Age Children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenbaum, B.F.; Zlotnik, A.; Frenkel, A.; Fleidervish, I.; Boyko, M. Glutamate Efflux across the Blood-Brain Barrier: New Perspectives on the Relationship between Depression and the Glutamatergic System. Metabolites 2022, 12, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, M.; Gruenbaum, B.F.; Oleshko, A.; Merzlikin, I.; Zlotnik, A. Diet’s Impact on Post-Traumatic Brain Injury Depression: Exploring Neurodegeneration, Chronic Blood–Brain Barrier Destruction, and Glutamate Neurotoxicity Mechanisms. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target Bacteria | MIC (mg/mL) |

|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus CIP 20256 | 1 |

| Kocuria rhizophila ATCC 10240 | 1 |

| Helicobacter pylori p12 | 1 |

| Helicobacter pylori 7.13 | 2 |

| Blautia coccoides DSM 935 | 8 |

| Listeria monocytogenes CIP 82110 | 16 |

| Listeria innocua CIP 106065 | 16 |

| Enterococcus faecalis CIP 76117 | 16 |

| Streptococcus mutans ATCC 35668 | 16 |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis ATCC 33277 | 16 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa CIP 76110 | 16 |

| Erwinia carotovora CECT 225 | 16 |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum ATCC 25586 | NC |

| Escherichia coli CIP 7624 | NC |

| Cutibacterium acnes DSM 1897 | NC |

| Pediococcus acidilactici DSM 20284 | NC |

| Lactobacillus plantarum 299v | NC |

| Akkermansia muciniphila DSM 22959 | NC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mokrani, M.; Brochot, A.; Urdaci, M.C. BiombalanceTM: A Specific Oligomeric Procyanidin-Rich Grape Seed Extract as Multifunctional Ingredient Integrating Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities with Beneficial Gut–Brain Axis Modulation. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121484

Mokrani M, Brochot A, Urdaci MC. BiombalanceTM: A Specific Oligomeric Procyanidin-Rich Grape Seed Extract as Multifunctional Ingredient Integrating Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities with Beneficial Gut–Brain Axis Modulation. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121484

Chicago/Turabian StyleMokrani, Mohamed, Amandine Brochot, and Maria C. Urdaci. 2025. "BiombalanceTM: A Specific Oligomeric Procyanidin-Rich Grape Seed Extract as Multifunctional Ingredient Integrating Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities with Beneficial Gut–Brain Axis Modulation" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121484

APA StyleMokrani, M., Brochot, A., & Urdaci, M. C. (2025). BiombalanceTM: A Specific Oligomeric Procyanidin-Rich Grape Seed Extract as Multifunctional Ingredient Integrating Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities with Beneficial Gut–Brain Axis Modulation. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121484