Spider Venom-Derived Peptide Exhibits Dual Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidative Activities in LPS-Stimulated BEAS-2B Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation and Transcriptome Analysis

2.2. Protein Prediction, Annotation, and Toxin Candidate Identification

2.3. In Silico-Based Therapeutic Peptide Predictions and Peptide Synthesis

2.4. Cell Culturing

2.5. Cell Viability Assay

2.6. Reverse Transcription-Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) Analysis

2.7. Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species Detection Assay

2.8. Immunocytochemistry Staining

2.9. Western Blotting Analysis

2.10. Radical Scavenging Assay

2.11. Ferrous Ion Chelating (FIC) Assay

2.12. Molecular Docking Simulation

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

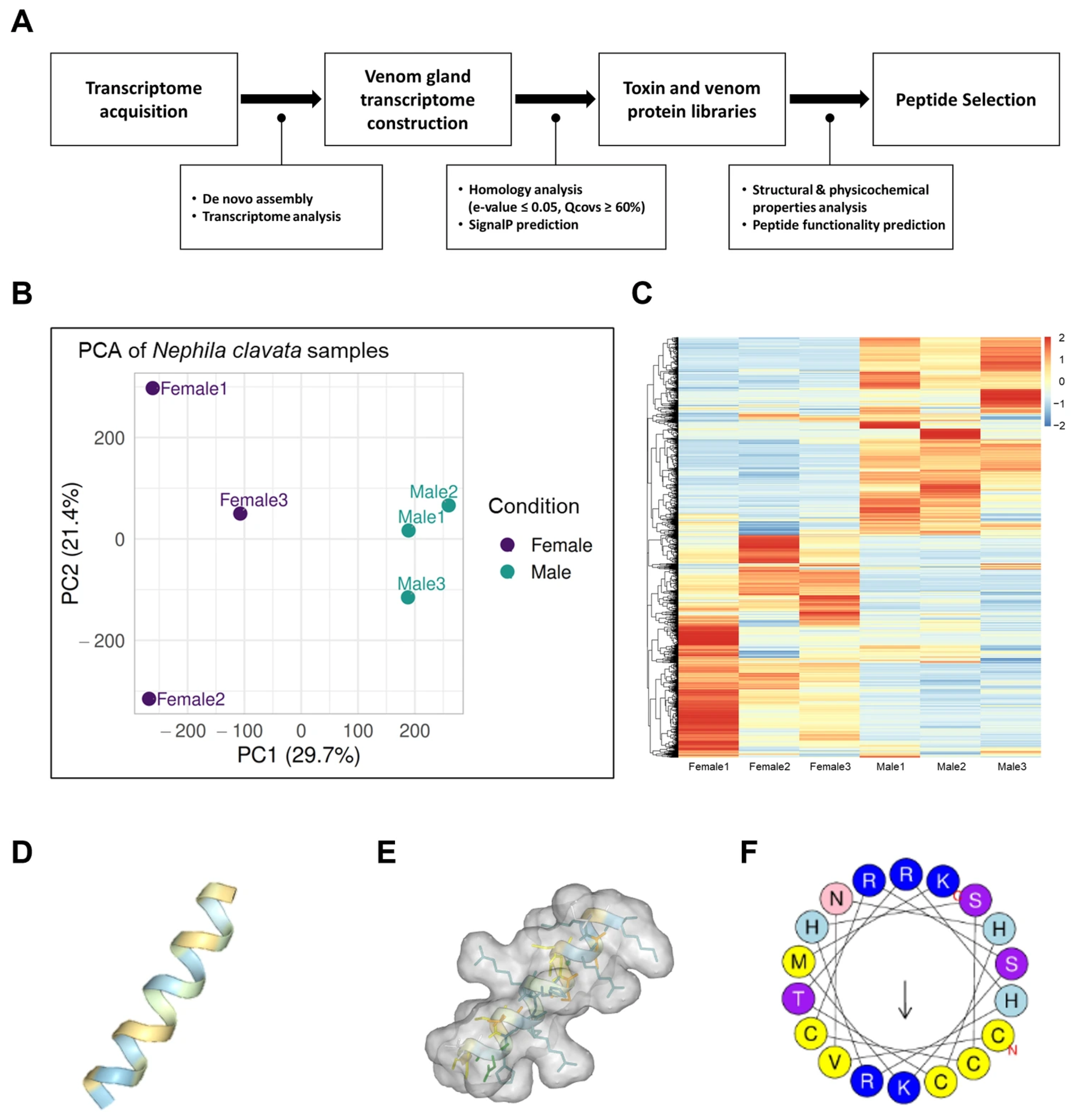

3.1. A Novel Functional Peptide from the N. clavata Venom Gland Transcriptome

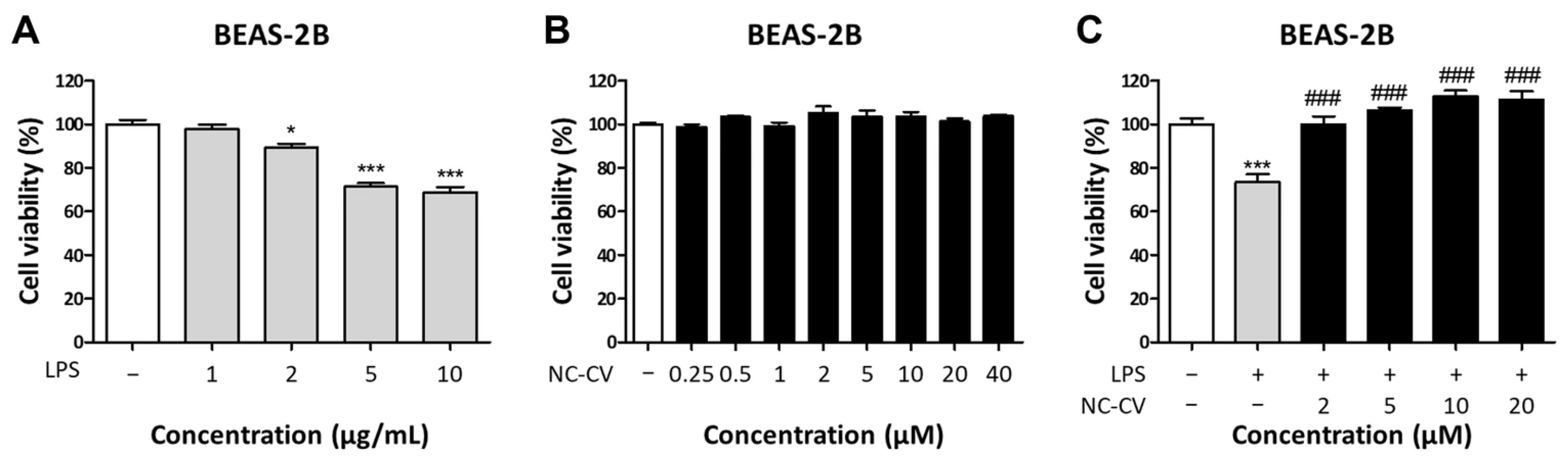

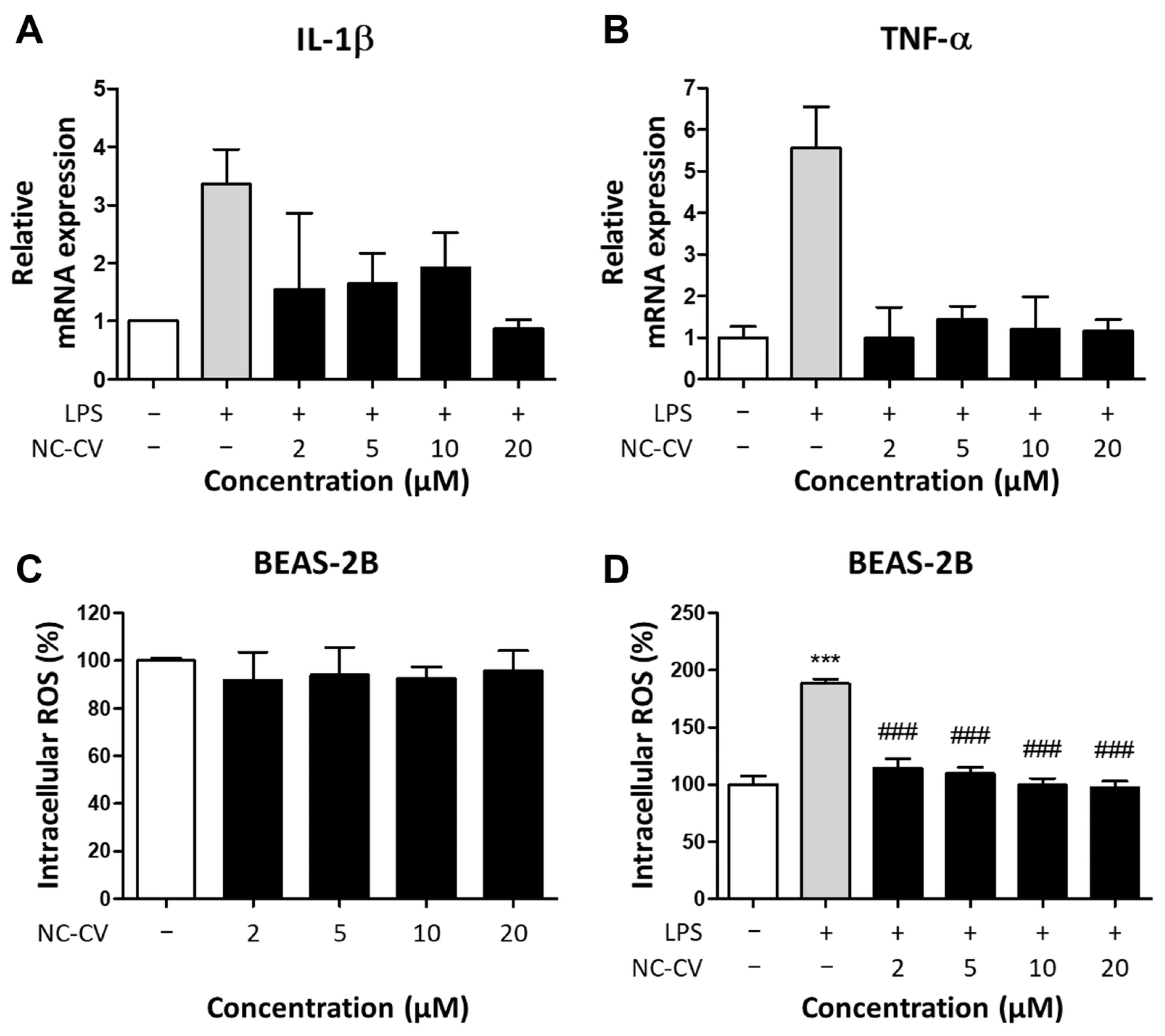

3.2. NC-CV Attenuates LPS-Induced Inflammation and ROS Production in BEAS-2B Cells

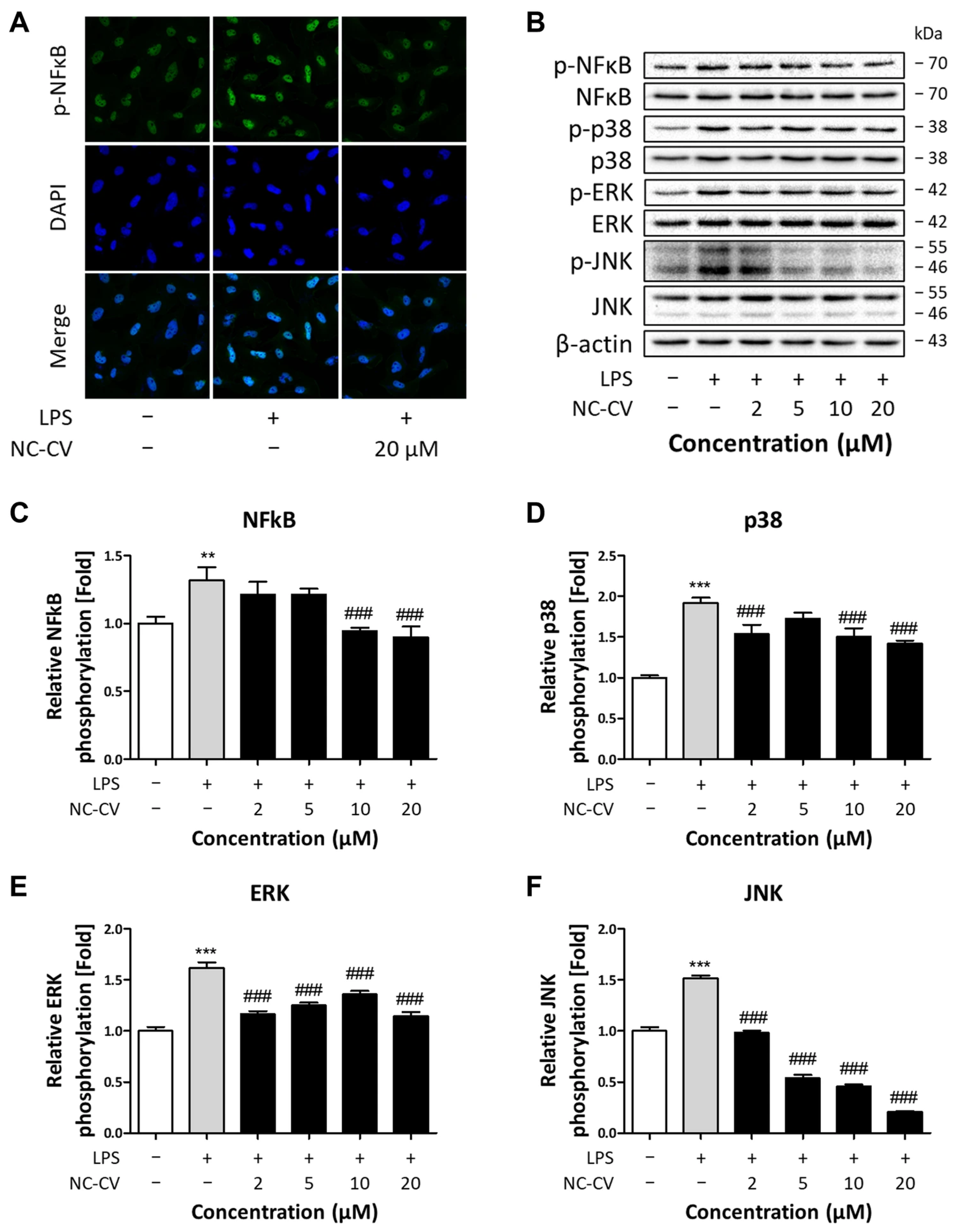

3.3. NC-CV Treatment Suppresses LPS-Induced MAPK/NFκB Pathway Activation in BEAS-2B Cells

3.4. NC-CV Exerts Antioxidative Activity Through Direct Radical Scavenging

3.5. Effect of NC-CV on NRF2 and Antioxidant Enzymes

3.6. Inhibition of TLR4 Dimerization by NC-CV Leads to Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidative Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferkol, T.; Schraufnagel, D. The global burden of respiratory disease. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2014, 11, 404–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.S.; Kim, S.R.; Lee, Y.C. Impact of oxidative stress on lung diseases. Respirology 2009, 14, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holguin, F. Oxidative stress in airway diseases. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2013, 10, S150–S157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshabanat, A.; Zafari, Z.; Albanyan, O.; Dairi, M.; FitzGerald, J. Asthma and COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS): A systematic review and meta analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, H.; Jun, K.; Lee, J.-Y. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of respiratory related hospitalizations in older patients with COPD, asthma, and bronchiectasis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchman, A.L. Side effects of corticosteroid therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2001, 33, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yin, S.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, W.; Dong, H.; Bai, Y.; Qin, Y.; Li, J.; Feng, S. LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression in human airway epithelial cells and macrophages via NF-κB, STAT3 or AP-1 activation. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 5484–5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, C.; Farkas, L.; Wolf, K.; Krätzel, K.; Eissner, G.; Pfeifer, M. Differences in LPS-induced activation of bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) and type II-like pneumocytes (A-549). Scand. J. Immunol. 2002, 56, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-C.; Yeh, W.-C.; Ohashi, P.S. LPS/TLR4 signal transduction pathway. Cytokine 2008, 42, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohto, U.; Fukase, K.; Miyake, K.; Shimizu, T. Structural basis of species-specific endotoxin sensing by innate immune receptor TLR4/MD-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7421–7426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Xu, L.; Zeng, Y.; Gong, F. Effect of gut microbiota on LPS-induced acute lung injury by regulating the TLR4/NF-kB signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 91, 107272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Min, J.-S.; Kim, B.; Chae, U.-B.; Yun, J.W.; Choi, M.-S.; Kong, I.-K.; Chang, K.-T.; Lee, D.-S. Mitochondrial ROS govern the LPS-induced pro-inflammatory response in microglia cells by regulating MAPK and NF-κB pathways. Neurosci. Lett. 2015, 584, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sul, O.-J.; Ra, S.W. Quercetin Prevents LPS-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation by Modulating NOX2/ROS/NF-kB in Lung Epithelial Cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 6949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Chun, J.N.; Jung, H.Y.; Choi, C.; Bae, Y.S. Role of NADPH oxidase 4 in lipopolysaccharide-induced proinflammatory responses by human aortic endothelial cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 72, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandekar, A.; Mendez, R.; Zhang, K. Cross Talk Between ER Stress, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in Health and Disease. In Stress Responses: Methods and Protocols; Oslowski, C.M., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, A.; Vázquez, A. Bioactive peptides: A review. Food Qual. Saf. 2017, 1, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daliri, E.B.-M.; Oh, D.H.; Lee, B.H. Bioactive Peptides. Foods 2017, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadar, M.; Shahali, Y.; Chakraborty, S.; Prasad, M.; Tahoori, F.; Tiwari, R.; Dhama, K. Antiinflammatory peptides: Current knowledge and promising prospects. Inflamm. Res. 2019, 68, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.H.; Hamdan, N.; Nyakuma, B.B.; Wong, S.L.; Wong, K.Y.; Tan, H.; Jamaluddin, H.; Lee, T.H. Purification, identification and molecular docking studies of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory peptides from Edible Bird’s Nest. Food Chem. 2024, 454, 139797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, F.-C.; Xiao, J.; Wang, S.; Ee, K.-Y.; Chai, T.-T. Advances on the antioxidant peptides from edible plant sources. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, R.E.W.; Sahl, H.-G. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1551–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, Z.F.; Kumar, S.; Bhat, H.F. Bioactive peptides of animal origin: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 5377–5392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Pirrung, M.; McCue, L.A. FQC Dashboard: Integrates FastQC results into a web-based, interactive, and extensible FASTQ quality control tool. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3137–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, M.; Berkeley, M.R.; Seppey, M.; Simão, F.A.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO update: Novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 4647–4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patro, R.; Duggal, G.; Love, M.I.; Irizarry, R.A.; Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, B.J.; Papanicolaou, A.; Yassour, M.; Grabherr, M.; Blood, P.D.; Bowden, J.; Couger, M.B.; Eccles, D.; Li, B.; Lieber, M. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 1494–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Sønderby, C.K.; Petersen, T.N.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabinski, L.; Jaroszewski, L.; Rychlewski, L.; Wilson, I.A.; Lesley, S.A.; Godzik, A. XtalPred: A web server for prediction of protein crystallizability. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 3403–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, J.; Murail, S.; de Vries, S.; Derreumaux, P.; Tuffery, P. PEP-FOLD4: A pH-dependent force field for peptide structure prediction in aqueous solution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W432–W437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautier, R.; Douguet, D.; Antonny, B.; Drin, G. HELIQUEST: A web server to screen sequences with specific α-helical properties. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 2101–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, T.H.; Yesiltas, B.; Marin, F.I.; Pertseva, M.; García-Moreno, P.J.; Gregersen, S.; Overgaard, M.T.; Jacobsen, C.; Lund, O.; Hansen, E.B. AnOxPePred: Using deep learning for the prediction of antioxidative properties of peptides. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Kong, T.; Liu, J. PepNet: An interpretable neural network for anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial peptides prediction using a pre-trained protein language model. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, M.S.; Hasan, M.M.; Kurata, H. PreAIP: Computational prediction of anti-inflammatory peptides by integrating multiple complementary features. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirtskhalava, M.; Amstrong, A.A.; Grigolava, M.; Chubinidze, M.; Alimbarashvili, E.; Vishnepolsky, B.; Gabrielian, A.; Rosenthal, A.; Hurt, D.E.; Tartakovsky, M. DBAASP v3: Database of antimicrobial/cytotoxic activity and structure of peptides as a resource for development of new therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D288–D297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; White, A.D. Serverless prediction of peptide properties with recurrent neural networks. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 2546–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.S.; Song, D.H.; Kim, H.M.; Choi, B.-S.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.-O. The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4–MD-2 complex. Nature 2009, 458, 1191–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: Making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2. 0: New docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krissinel, E.; Henrick, K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 372, 774–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzig, V.; Khalife, A.A.; Chong, Y.; Isbister, G.K.; Currie, B.J.; Churchill, T.B.; Horner, S.; Escoubas, P.; Nicholson, G.M.; Hodgson, W.C. Intersexual variations in Northern (Missulena pruinosa) and Eastern (M. bradleyi) mouse spider venom. Toxicon 2008, 51, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zobel-Thropp, P.A.; Bulger, E.A.; Cordes, M.H.; Binford, G.J.; Gillespie, R.G.; Brewer, M.S. Sexually dimorphic venom proteins in long-jawed orb-weaving spiders (Tetragnatha) comprise novel gene families. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, R.; Honda, R.; Kanome, M.; Hagiwara, A.; Matsuda, Y.; Togitani, T.; Ikemoto, N.; Terashima, M. Designing antioxidant peptides based on the antioxidant properties of the amino acid side-chains. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 750–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Castilla, J.; Hernández-Álvarez, A.J.; Jiménez-Martínez, C.; Jacinto-Hernández, C.; Alaiz, M.; Girón-Calle, J.; Vioque, J.; Dávila-Ortiz, G. Antioxidant and metal chelating activities of peptide fractions from phaseolin and bean protein hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1789–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattis, D.M.; Chervin, A.S.; Ranoa, D.R.; Kelley, S.L.; Tapping, R.I.; Kranz, D.M. Studies of the TLR4-associated protein MD-2 using yeast-display and mutational analyses. Mol. Immunol. 2015, 68, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Li, W.; He, S.; Guo, L.; Liu, K.; Dong, J.; Li, J.; Wang, H. Inhibition of NOX4-Mediated ROS Production Contributes to Selenomethionine’s Anti-Inflammatory Effect in LPS-Stimulated Bovine Endometrial Epithelial Cells. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Quan, Z.; Xiao, P.; Duan, J.-A. New insights into antioxidant peptides: An overview of efficient screening, evaluation models, molecular mechanisms, and applications. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.J.; Yudin, A.K. Contemporary strategies for peptide macrocyclization. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, L.; Fersht, A.R. Capping and α-helix stability. Nature 1989, 342, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentilucci, L.; De Marco, R.; Cerisoli, L. Chemical modifications designed to improve peptide stability: Incorporation of non-natural amino acids, pseudo-peptide bonds, and cyclization. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010, 16, 3185–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, E.; Kitas, E.; Seelig, J. Binding of oligoarginine to membrane lipids and heparan sulfate: Structural and thermodynamic characterization of a cell-penetrating peptide. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 2692–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sani, M.-A.; Separovic, F. How membrane-active peptides get into lipid membranes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target Gene | Forward Primer (5′ → 3′) | Reverse Primer (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | AACTGGAACGGTGAAGGT | CCTGTAACAACGCATCTCATAT |

| IL-1β | AGGATATGGAGCAACAAGT | ATCATCTTT CAACACGCAG |

| TNF-α | TTAAGCAACAAGACCACCA | CTCCAGATTCCAGATGTCA |

| Peptide | Sequence | Molecular Weight | Net Charge | Water Solubility | PI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC-CV | CVNHCTRHRHSCCRSKMK | 2186.56 g/mol | +5 | Good | 10.22 |

| Peptide | AIP Prediction | AOP Prediction | Hemolysis Prediction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PepNet | PreAIP | AIPID | AnOxPpred | Peptide.bio | DBAASP | |

| NC-CV | 0.713 | 0.653 | 0.81 | 0.482 | Not active | Not active |

| Peptide | Sequence (Length) | Net Charge | Antioxidative Amino Acids (No. of Residues) | Radical Scavenging Activity (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y, W | C, M | H, K, R | Total | ||||

| Pep1 | VVSTTSYCKKMKKDCNDYTK (20) | +2.9 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 72.57 |

| Pep2 | VRKLTRYCKKMKKDCKRYWK (20) | +8.9 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 14 | 52.03 |

| Pep3 | GADCCVVSTTSYCKKMKKDC (20) | +1.7 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 59.44 |

| Pep4 | AAKRCVRSWTRYCKKMKKDC (20) | +6.8 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 11 | 28.75 |

| Pep5 | MMGHRCRAMKCMKKVHDK (20) | +5.1 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 12 | 57.50 |

| Pep6 | MMKHMCRAMKCMKKVMDK (20) | +5 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 69.75 |

| Pep7 | TCVNHCTRHRHSCCRSKM (18) | +4 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 12 | 63.14 |

| NC-CV | CVNHCTRHRHSCCRSKMK (18) | +5 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 13 | 84.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oh, J.W.; Shin, M.K.; Park, H.-R.; Jeong, S.; Lee, M.; Ko, J.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Jee, S.-C.; Sung, J.-S. Spider Venom-Derived Peptide Exhibits Dual Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidative Activities in LPS-Stimulated BEAS-2B Cells. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1485. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121485

Oh JW, Shin MK, Park H-R, Jeong S, Lee M, Ko JH, Lee JY, Jee S-C, Sung J-S. Spider Venom-Derived Peptide Exhibits Dual Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidative Activities in LPS-Stimulated BEAS-2B Cells. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1485. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121485

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Jin Wook, Min Kyoung Shin, Hye-Ran Park, Sukin Jeong, Minho Lee, Ji Hyuk Ko, Jae Young Lee, Seung-Cheol Jee, and Jung-Suk Sung. 2025. "Spider Venom-Derived Peptide Exhibits Dual Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidative Activities in LPS-Stimulated BEAS-2B Cells" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1485. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121485

APA StyleOh, J. W., Shin, M. K., Park, H.-R., Jeong, S., Lee, M., Ko, J. H., Lee, J. Y., Jee, S.-C., & Sung, J.-S. (2025). Spider Venom-Derived Peptide Exhibits Dual Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidative Activities in LPS-Stimulated BEAS-2B Cells. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1485. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121485