Lactarius deliciosus Extract from Green Microwave-Assisted Eutectic Solvent Extraction as a Therapeutic Candidate Against Colon Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Collection

2.2. Extraction Conditions and Extract Preparation

2.3. Determination of Phenolic Content and Composition

2.4. Determination of Antioxidant Activity

2.5. Cell Culture

2.6. Clonogenic Assay

2.7. Adhesion Assay

2.8. Cytotoxicity Determination

2.9. Cell Death Studies

2.10. Analysis of Cell Cycle and DNA Content

2.11. The Determination of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and Caspase-3 Activity by Flow Cytometry

2.12. Determination of Intracellular Levels of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

2.13. mRNA Expression Levels of NOS2, PTGS2, IL-6 and IL-8

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

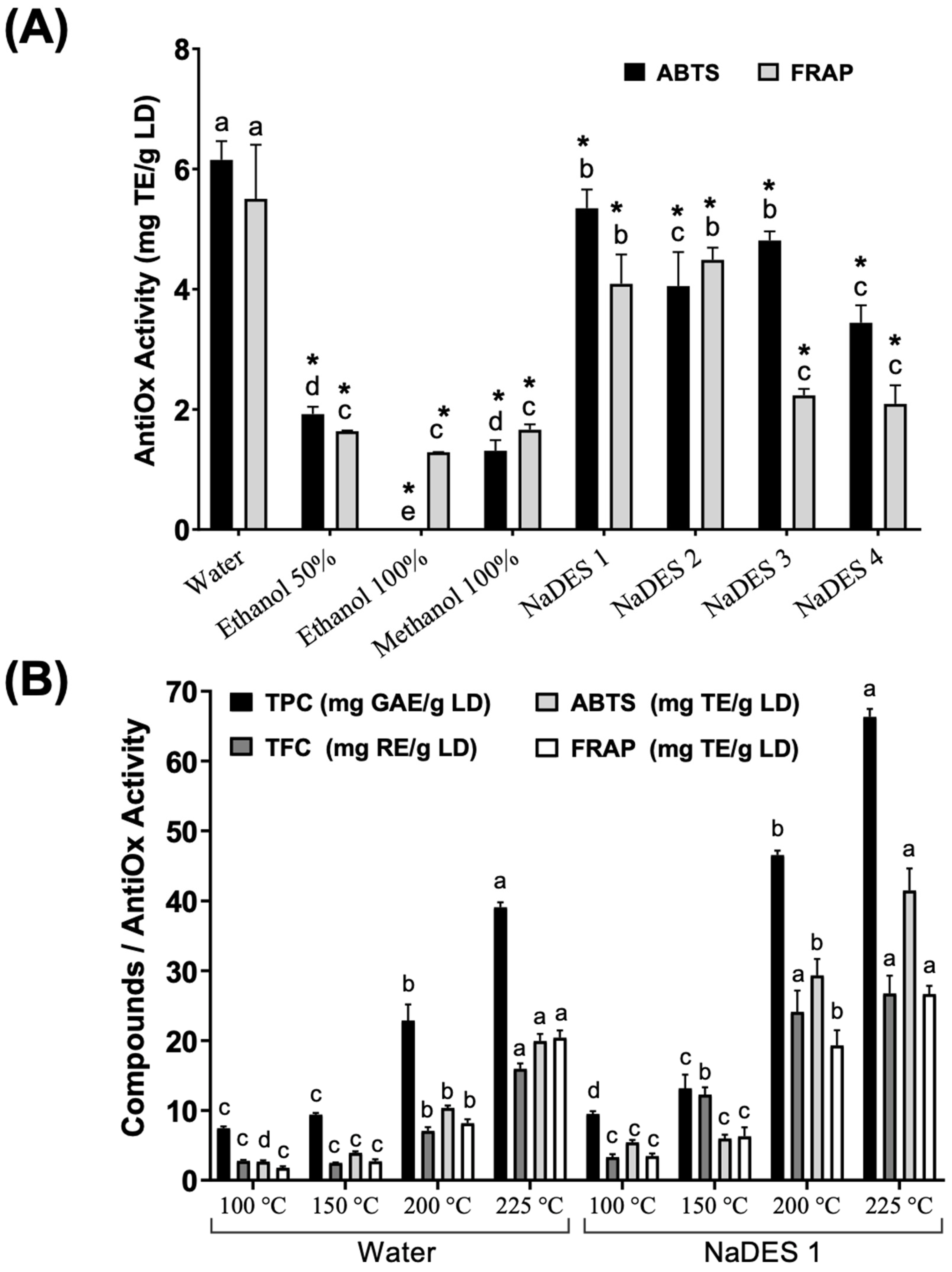

3.1. Extraction of LDE

3.2. Chemical Composition of LDE

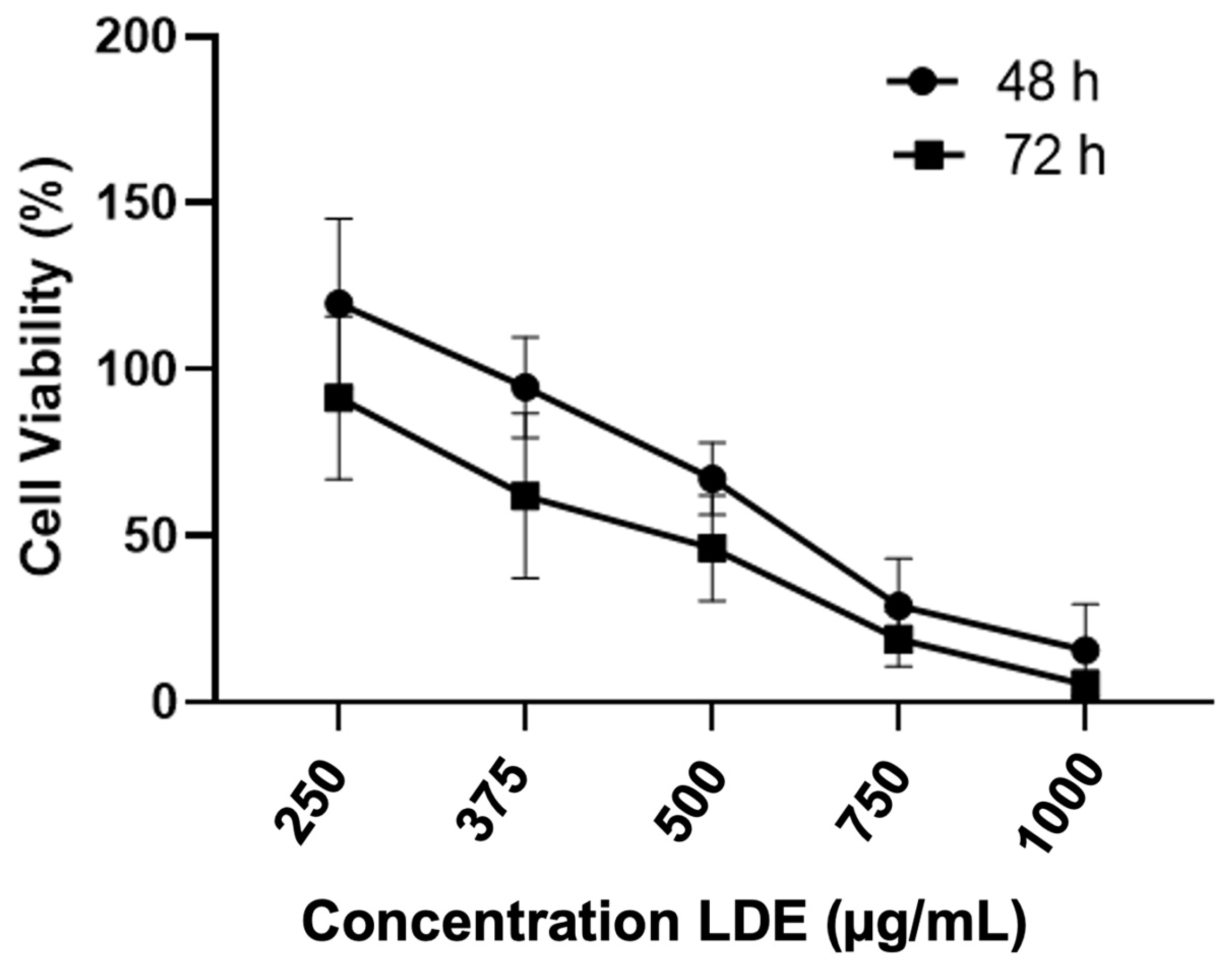

3.3. Effect of LDE on Caco-2 Cell Viability

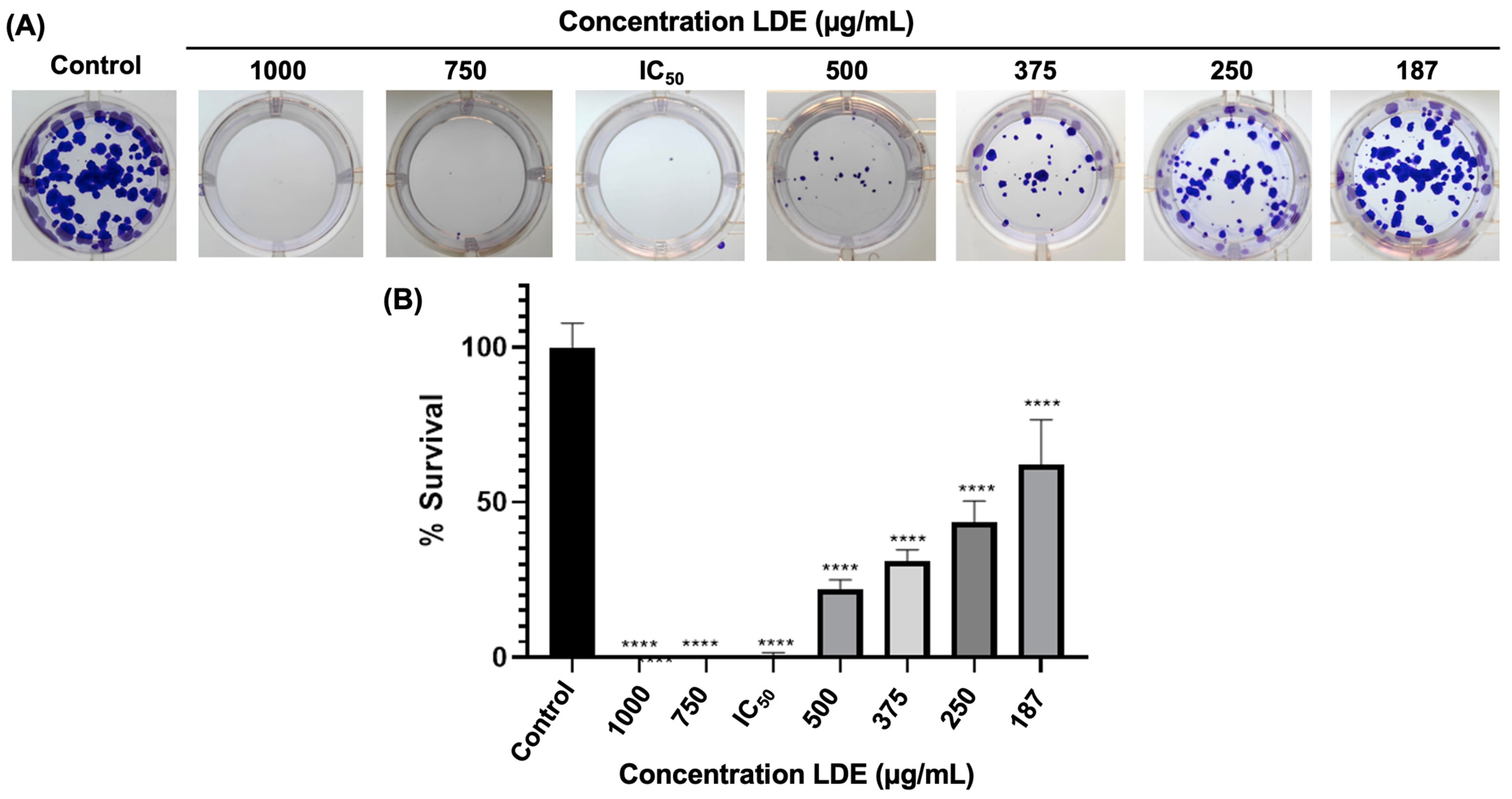

3.4. Clonogenic Survival of Caco-2 Cells

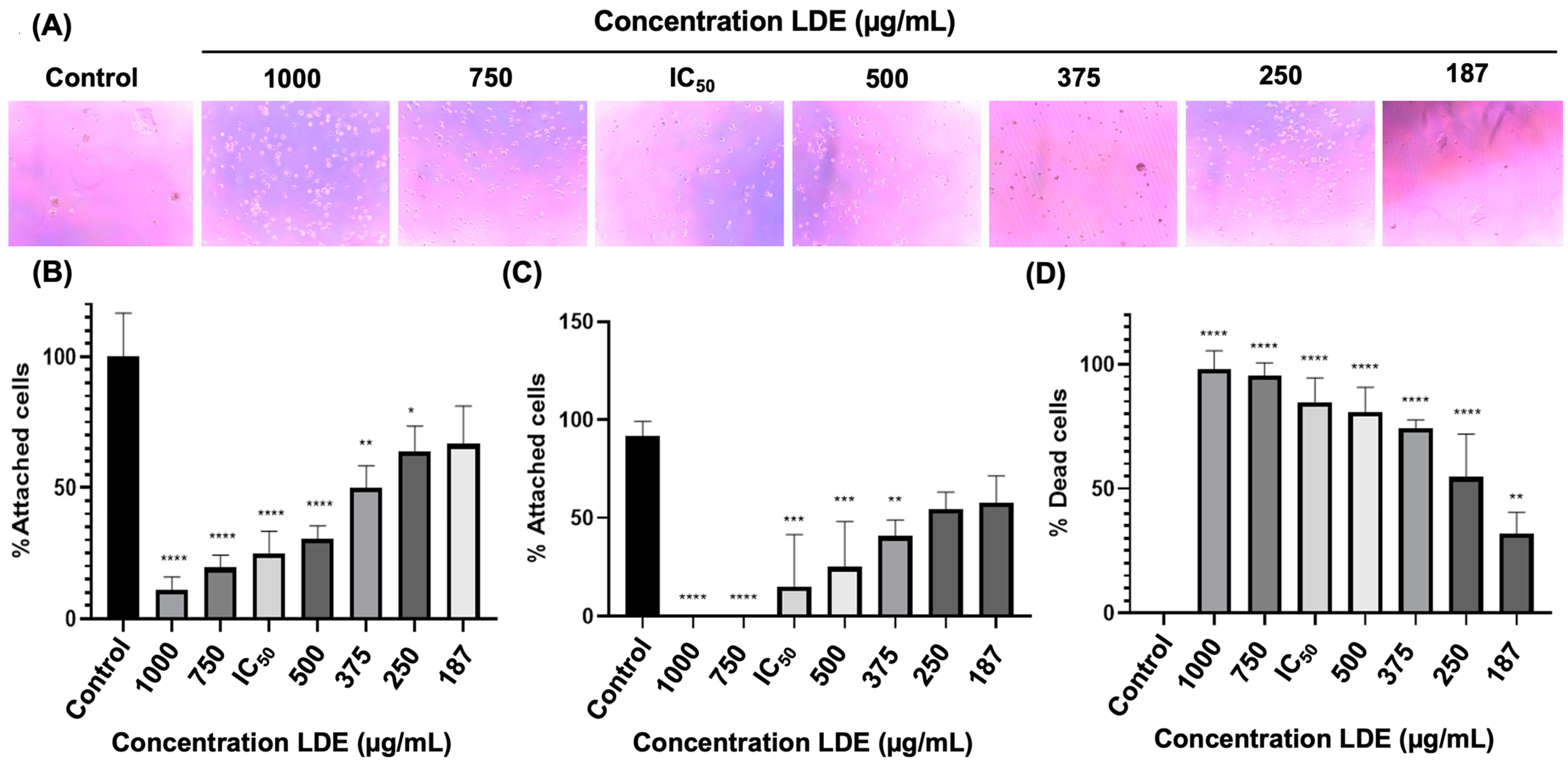

3.5. LDE Effects on Cell Adhesion of Caco-2

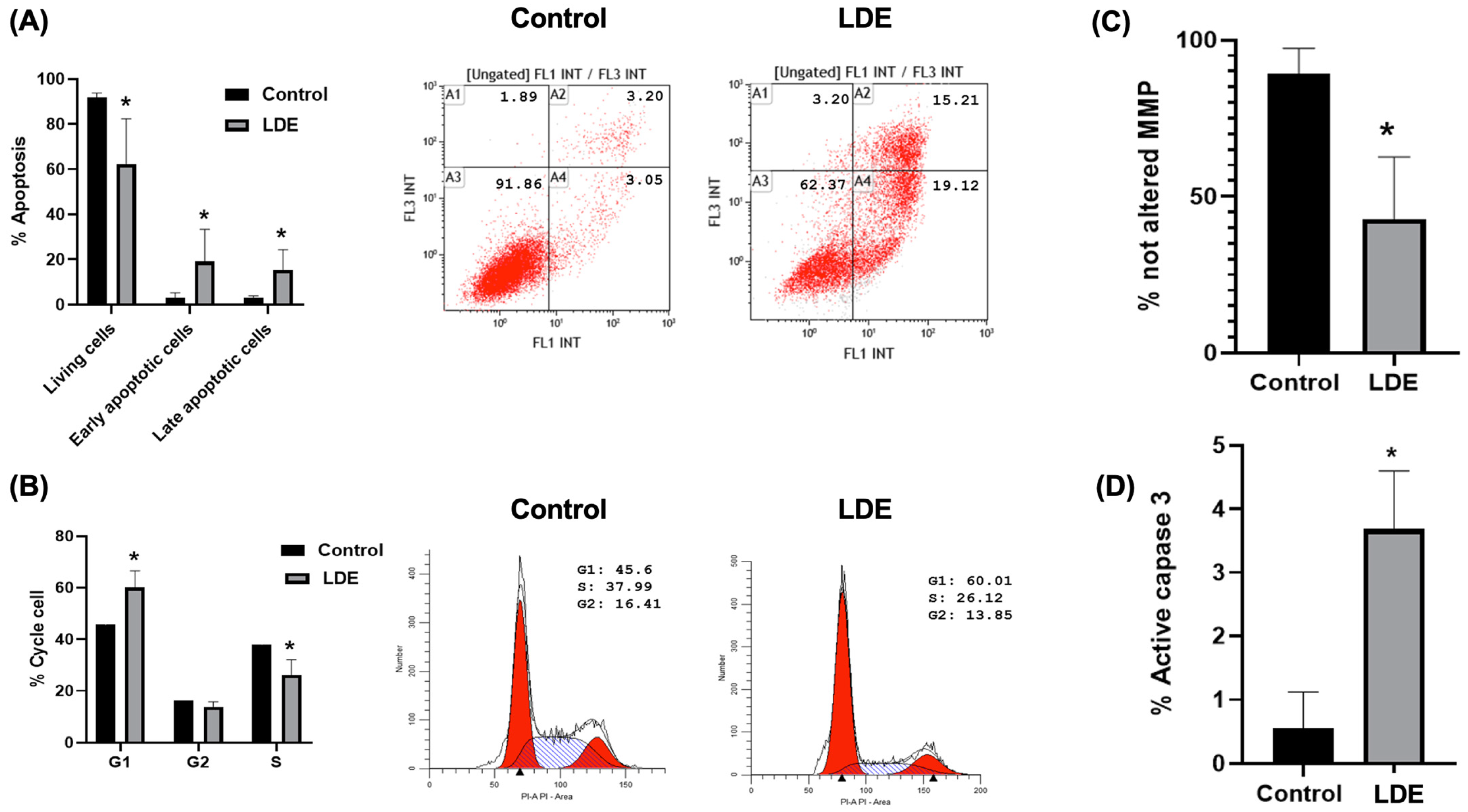

3.6. Induction of Cellular Death (Apoptosis, Cell Cycle, Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and Caspase 3 Activity) by LDE

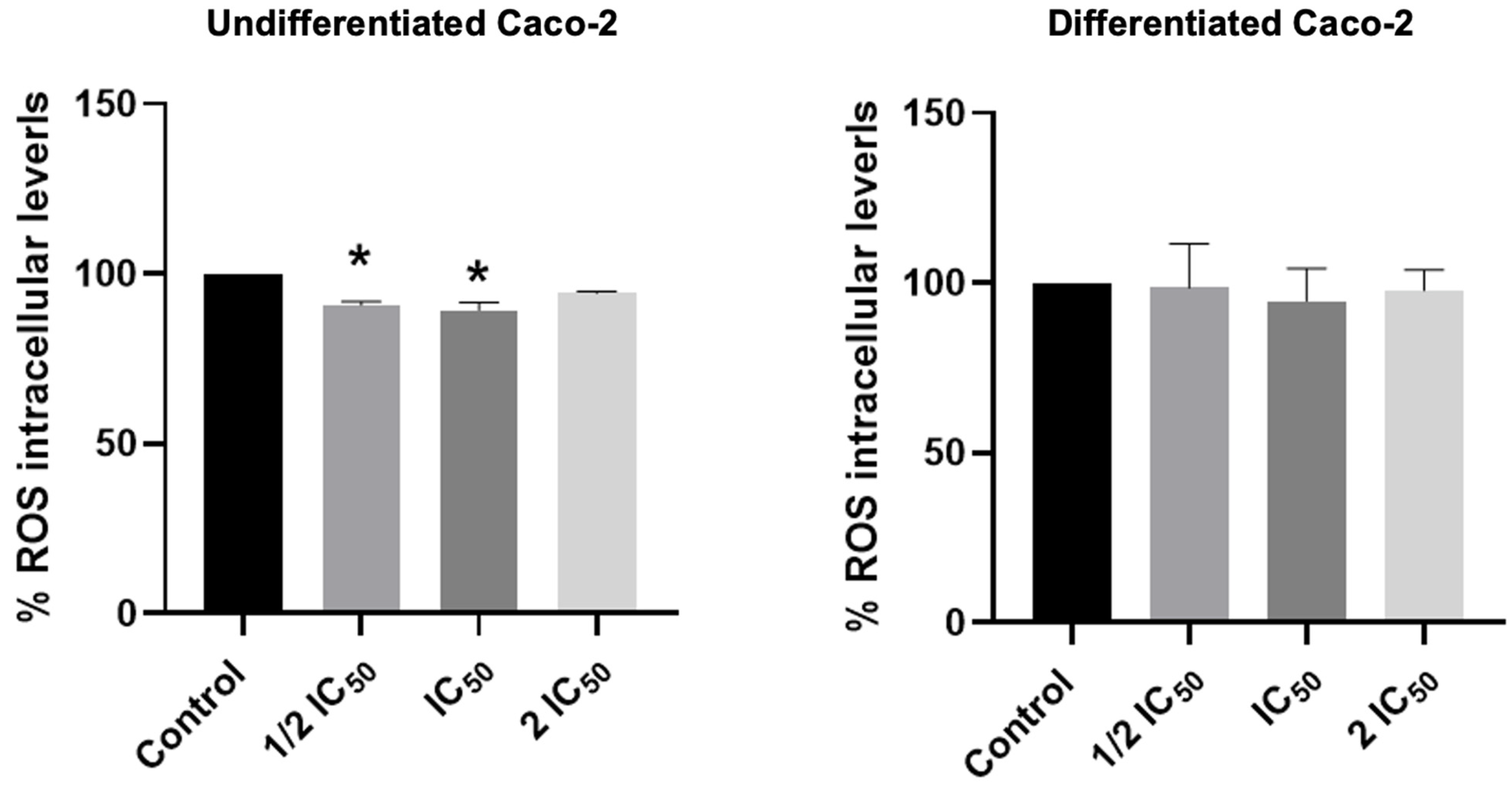

3.7. Effect of LDE on Intracellular ROS Levels

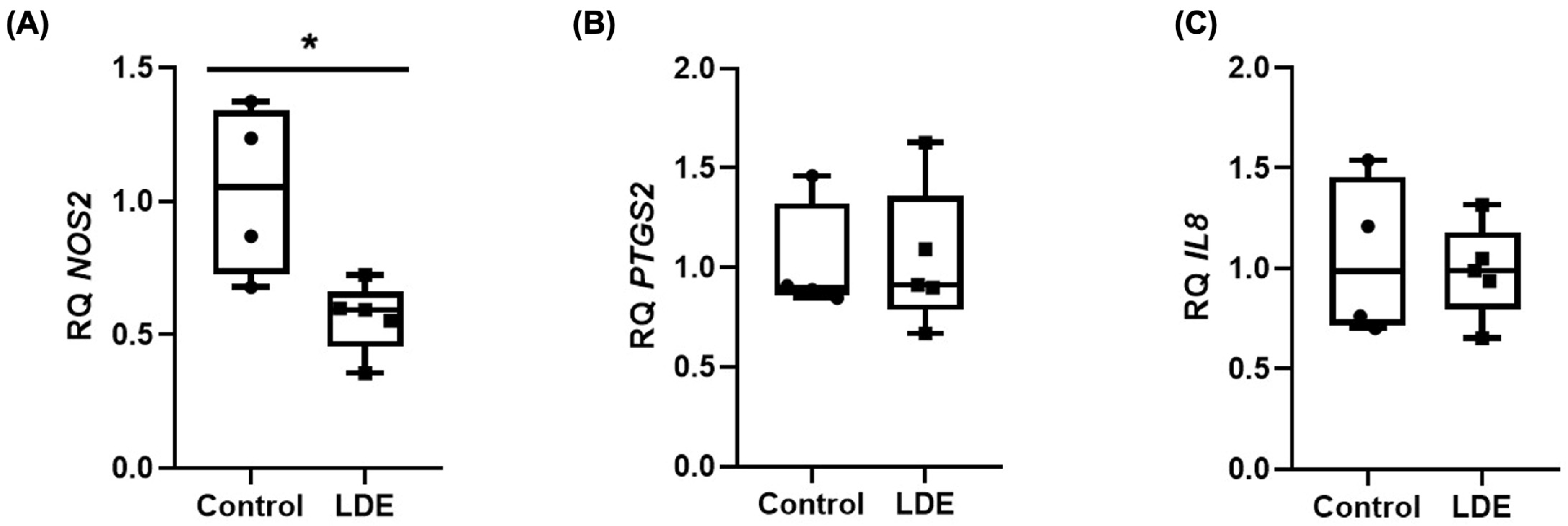

3.8. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of LDE

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sousa, A.S.; Araújo-Rodrigues, H.; Pintado, M.E. The Health-Promoting Potential of Edible Mushroom Proteins. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2023, 29, 804–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breene, W.M. Nutritional and Medicinal Value of Specialty Mushrooms. J. Food Prot. 1990, 53, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, K.B.; Malakar, R.; Kumar, A.; Sarma, N.; Jha, D.K. Ecofriendly Utilization of Lignocellulosic Wastes: Mushroom Cultivation and Value Addition. In Value-Addition in Agri-Food Industry Waste Through Enzyme Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Alkan, S.; Uysal, A.; Kasik, G.; Vlaisavljevic, S.; Berežni, S.; Zengin, G. Chemical Characterization, Antioxidant, Enzyme Inhibition and Antimutagenic Properties of Eight Mushroom Species: A Comparative Study. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosanić, M.; Ranković, B.; Rančić, A.; Stanojković, T. Evaluation of Metal Concentration and Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Anticancer Potentials of Two Edible Mushrooms Lactarius deliciosus and Macrolepiota Procera. J. Food Drug Anal. 2016, 24, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, R.; Smith, J.E.; Rowan, N.J. Medicinal Mushrooms and Cancer Therapy: Translating a Traditional Practice into Western Medicine. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2006, 49, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Hou, Y.; Hou, W. Structure Feature and Antitumor Activity of a Novel Polysaccharide Isolated from Lactarius deliciosus Gray. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 89, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowakowski, P.; Markiewicz-Żukowska, R.; Gromkowska-Kępka, K.; Naliwajko, S.K.; Moskwa, J.; Bielecka, J.; Grabia, M.; Borawska, M.; Socha, K. Mushrooms as Potential Therapeutic Agents in the Treatment of Cancer: Evaluation of Anti-Glioma Effects of Coprinus comatus, Cantharellus cibarius, Lycoperdon perlatum and Lactarius deliciosus Extracts. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 133, 111090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, G.B.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Ferreira, A.L.A.; Xavier, L.O.; Veloso, N.C.; da Silva, J.; de Oliveira, G.P.; Amaral, N.C.; de Lima Veeck, A.P.; Ferrareze, J.P. Investigation of Nutritional Composition, Antioxidant Compounds, and Antimicrobial Activity of Wild Culinary-Medicinal Mushrooms Boletus edulis and Lactarius deliciosus (Agaricomycetes) from Brazil. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2020, 22, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, A.; Uyar, A.; Hasar, S.; Keles, O.F. The Protective Effects of the Lactarius deliciosus and Agrocybe cylindracea Mushrooms on Histopathology of Carbon Tetrachloride Induced Oxidative Stress in Rats. Biotech. Histochem. 2022, 97, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Akash, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Nowrin, F.T.; Akter, T.; Shohag, S.; Rauf, A.; Aljohani, A.S.M.; Simal-Gandara, J. Colon Cancer and Colorectal Cancer: Prevention and Treatment by Potential Natural Products. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 368, 110170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, A.B.; Venook, A.P.; Al-Hawary, M.M.; Arain, M.A.; Chen, Y.-J.; Ciombor, K.K.; Cohen, S.; Cooper, H.S.; Deming, D.; Farkas, L. Colon Cancer, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 329–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Duan, J.-J.; Bian, X.-W.; Yu, S. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Molecular Subtyping and Treatment Progress. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, E.; Attri, D.C.; Sati, P.; Dhyani, P.; Szopa, A.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Hano, C.; Calina, D.; Cho, W.C. Recent Updates on Anticancer Mechanisms of Polyphenols. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1005910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira-Santos, P.; Martinez, B.R.; Colussi, F.; Perez, A.R.; Yáñez, R.; Garrote, G.; del Rio, P.G.; Gullón, B. Alternative Solvents for Green Extraction of Bioactive Compounds. In Application of Emerging Technologies and Strategies to Extract Bioactive Compounds; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 323–367. [Google Scholar]

- Mansinhos, I.; Goncalves, S.; Rodriguez-Solana, R.; Ordonez-Diaz, J.L.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M.; Romano, A. Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction and Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents Combination: A Green Strategy to Improve the Recovery of Phenolic Compounds from Lavandula Pedunculata subsp. Lusitanica (Chaytor) Franco. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaouhari, Y.; Bordiga, M.; Travaglia, F.; Coisson, J.-D.; Costa-Barbosa, A.; Sampaio, P.; Botelho, C.; Gullón, B.; Ferreira-Santos, P. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Raspberry Pomace Phenolic Compounds, and Their Bioaccessibility and Bioactivity. Food Chem. 2025, 478, 143641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaredo-López-Vizcaíno, A.; Costa-Barbosa, A.; Sampaio, P.; Del Río, P.G.; Botelho, C.; Ferreira-Santos, P. Development of Cytisus Flower Extracts with Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties for Nutraceutical and Food Uses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quero, J.; Alconchel, A.; Ortega, S.; Bidooki, S.H.; Gimeno, M.C.; Rodriguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Cerrada, E. N-Heterocyclic Carbene Gold (I) Derivatives with Long Aliphatic Side Chains as Potential Anticancer Agents in Colon Cancer. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2025, 272, 112987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidooki, S.H.; Quero, J.; Sánchez-Marco, J.; Herrero-Continente, T.; Marmol, I.; Lasheras, R.; Sebastian, V.; Arruebo, M.; Osada, J.; Rodriguez-Yoldi, M.J. Squalene in Nanoparticles Improves Antiproliferative Effect on Human Colon Carcinoma Cells Through Apoptosis by Disturbances in Redox Balance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, N.A.P.; Rodermond, H.M.; Stap, J.; Haveman, J.; Van Bree, C. Clonogenic Assay of Cells in Vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2315–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzarski, J.S.; DiVito, M.D.; Wertheim, J.A.; Miller, W.M. Essential Design Considerations for the Resazurin Reduction Assay to Noninvasively Quantify Cell Expansion within Perfused Extracellular Matrix Scaffolds. Biomaterials 2017, 129, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quero, J.; Ballesteros, L.F.; Ferreira-Santos, P.; Velderrain-Rodriguez, G.R.; Rocha, C.M.R.; Pereira, R.N.; Teixeira, J.A.; Martin-Belloso, O.; Osada, J.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J. Unveiling the Antioxidant Therapeutic Functionality of Sustainable Olive Pomace Active Ingredients. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-de-Diego, C.; Marmol, I.; Perez, R.; Gascon, S.; Rodriguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Cerrada, E. The Anticancer Effect Related to Disturbances in Redox Balance on Caco-2 Cells Caused by an Alkynyl Gold (I) Complex. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2017, 166, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, C.; Palacios, I.; Lozano, M.; D’Arrigo, M.; Guillamón, E.; Villares, A.; Martínez, J.A.; García-Lafuente, A. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Methanolic Extracts from Edible Mushrooms in LPS Activated RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Food Chem. 2012, 130, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feussi Tala, M.; Qin, J.; Ndongo, J.T.; Laatsch, H. New Azulene-Type Sesquiterpenoids from the Fruiting Bodies of Lactarius deliciosus. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2017, 7, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Ding, X.; Hou, W.; Song, B.; Wang, T.; Wang, F.; Zhong, J. Immunostimulant Activity of a Novel Polysaccharide Isolated from Lactarius deliciosus (L. Ex. Fr.) Gray. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 75, 393. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez-Correa, E.; Bastías-Montes, J.M.; Acuña-Nelson, S.; Muñoz-Fariña, O. Effect of Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents on Polyphenols Extraction from Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) Bean Shells and Antioxidant Activity of Extracts. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Ali Redha, A.; Salauddin, M.; Harahap, I.A.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Factors Affecting the Extraction of (Poly) Phenols from Natural Resources Using Deep Eutectic Solvents Combined with Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2025, 55, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscarella, M.; Nardi, M.; Alipieva, K.; Bonacci, S.; Popova, M.; Procopio, A.; Scarpelli, R.; Simeonov, S. Alternative Assisted Extraction Methods of Phenolic Compounds Using NaDESs. Antioxidants 2023, 13, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Castillo-Llamosas, A.; Eibes, G.; Ferreira-Santos, P.; Pérez-Pérez, A.; Del-Río, P.G.; Gullón, B. Microwave-Assisted Autohydrolysis of Avocado Seed for the Recovery of Antioxidant Phenolics and Glucose. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 385, 129432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Yadav, S.S. A Review on Health Benefits of Phenolics Derived from Dietary Spices. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 1508–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, I.; Seccia, S.; Senatore, A.; Coppola, D.; Morelli, E. Development and Validation of an Analytical Method for Total Polyphenols Quantification in Extra Virgin Olive Oils. Food Anal. Methods 2020, 13, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimir-Knežević, S.; Blažeković, B.; Bival Štefan, M.; Babac, M. Plant Polyphenols as Antioxidants Influencing the Human Health. In Phytochemicals as Nutraceuticals–Global Approaches to Their Role in Nutrition and Health; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; pp. 155–180. [Google Scholar]

- Azmi, A.S.; Bhat, S.H.; Hanif, S.; Hadi, S.M. Plant Polyphenols Mobilize Endogenous Copper in Human Peripheral Lymphocytes Leading to Oxidative DNA Breakage: A Putative Mechanism for Anticancer Properties. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostić, M.; Ivanov, M.; Fernandes, Â.; Calhelha, R.C.; Glamočlija, J.; Barros, L.; Soković, M.; Ćirić, A. A Comparative Study of Lactarius Mushrooms: Chemical Characterization, Antibacterial, Antibiofilm, Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activity. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, L.; Dueñas, M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Baptista, P.; Santos-Buelga, C. Phenolic Acids Determination by HPLC–DAD–ESI/MS in Sixteen Different Portuguese Wild Mushrooms Species. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 1076–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdeja, J.G.; Madduri, D.; Usmani, S.Z.; Jakubowiak, A.; Agha, M.; Cohen, A.D.; Stewart, A.K.; Hari, P.; Htut, M.; Lesokhin, A. Ciltacabtagene Autoleucel, a B-Cell Maturation Antigen-Directed Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): A Phase 1b/2 Open-Label Study. Lancet 2021, 398, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Mumper, R.J. Plant Phenolics: Extraction, Analysis and Their Antioxidant and Anticancer Properties. Molecules 2010, 15, 7313–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quero, J.; Paesa, M.; Morales, C.; Mendoza, G.; Osada, J.; Teixeira, J.A.; Ferreira-Santos, P.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J. Biological Properties of Boletus edulis Extract on Caco-2 Cells: Antioxidant, Anticancer, and Anti-Inflammatory Effects. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- c Ooi, V.E.; Liu, F. Immunomodulation and Anti-Cancer Activity of Polysaccharide-Protein Complexes. Curr. Med. Chem. 2000, 7, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.C.; Muñoz-Pinedo, C.; Ricci, J.E.; Adams, S.R.; Kelekar, A.; Schuler, M.; Tsien, R.Y.; Green, D.R. Cytochrome c Is Released in a Single Step during Apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2005, 12, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velderrain-Rodriguez, G.R.; Quero, J.; Osada, J.; Martin-Belloso, O.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J. Phenolic-Rich Extracts from Avocado Fruit Residues as Functional Food Ingredients with Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Properties. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemieszek, M.K.; Nunes, F.M.; Marques, G.; Rzeski, W. Cantharellus cibarius Branched Mannans Inhibits Colon Cancer Cells Growth by Interfering with Signals Transduction in NF-ĸB Pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 134, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada-Barreiro, S.; Bravo-Diaz, C. Free Radicals and Polyphenols: The Redox Chemistry of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 133, 379–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofseth, L.J.; Hussain, S.P.; Wogan, G.N.; Harris, C.C. Nitric Oxide in Cancer and Chemoprevention. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 34, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendary, E.; Francis, R.R.; Ali, H.M.G.; Sarwat, M.I.; El Hady, S. Antioxidant and Structure–Activity Relationships (SARs) of Some Phenolic and Anilines Compounds. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2013, 58, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambuy, Y.; De Angelis, I.; Ranaldi, G.; Scarino, M.L.; Stammati, A.; Zucco, F. The Caco-2 Cell Line as a Model of the Intestinal Barrier: Influence of Cell and Culture-Related Factors on Caco-2 Cell Functional Characteristics. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2005, 21, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, M.; Robine-Leon, S.; Appay, M.-D.; Kedinger, M.; Triadou, N.; Dussaulx, E.; Lacroix, B.; Simon-Assmann, P.; Haffen, K.; Fogh, J. Enterocyte-like Differentiation and Polarization of the Human Colon Carcinoma Cell Line Caco-2 in Culture. Biol. Cell 1983, 47, 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Zeller, P.; Bricks, T.; Vidal, G.; Jacques, S.; Anton, P.M.; Leclerc, E. Multiparametric Temporal Analysis of the Caco-2/TC7 Demonstrated Functional and Differentiated Monolayers as Early as 14 Days of Culture. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantret, I.; Rodolosse, A.; Barbat, A.; Dussaulx, E.; Brot-Laroche, E.; Zweibaum, A.; Rousset, M. Differential Expression of Sucrase-Isomaltase in Clones Isolated from Early and Late Passages of the Cell Line Caco-2: Evidence for Glucose-Dependent Negative Regulation. J. Cell Sci. 1994, 107, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeer, R.S.; Mahmoud, S.M.; Amin, H.K.; Moneim, A.E.A. Ziziphus Spina-Christi Fruit Extract Suppresses Oxidative Stress and P38 MAPK Expression in Ulcerative Colitis in Rats via Induction of Nrf2 and HO-1 Expression. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 115, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.L.; Pandey, A.; Verma, S.; Das, P. Protection Afforded by Methanol Extract of Calotropis Procera Latex in Experimental Model of Colitis Is Mediated through Inhibition of Oxidative Stress and Pro-Inflammatory Signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1602–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taofiq, O.; Martins, A.; Barreiro, M.F.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Mushroom Extracts and Isolated Metabolites. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taofiq, O.; Calhelha, R.C.; Heleno, S.; Barros, L.; Martins, A.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Queiroz, M.J.R.P.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. The Contribution of Phenolic Acids to the Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Mushrooms: Screening in Phenolic Extracts, Individual Parent Molecules and Synthesized Glucuronated and Methylated Derivatives. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Tae, N.; Lee, S.; Ryoo, S.; Min, B.-S.; Lee, J.-H. Anti-Inflammatory and Heme Oxygenase-1 Inducing Activities of Lanostane Triterpenes Isolated from Mushroom Ganoderma Lucidum in RAW264. 7 Cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014, 280, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Tan, N.H.; Fung, S.Y.; Sim, S.M.; Tan, C.S.; Ng, S.T. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of the Sclerotium of Lignosus rhinocerotis (Cooke) Ryvarden, the Tiger Milk Mushroom. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, D.; Bennett, L.; Shanmugam, K.; King, K.; Williams, R.; Zabaras, D.; Head, R.; Ooi, L.; Gyengesi, E.; Münch, G. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Five Commercially Available Mushroom Species Determined in Lipopolysaccharide and Interferon-γ Activated Murine Macrophages. Food Chem. 2014, 148, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedinak, A.; Dudhgaonkar, S.; Wu, Q.; Simon, J.; Sliva, D. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Edible Oyster Mushroom Is Mediated through the Inhibition of NF-ΚB and AP-1 Signaling. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fangkrathok, N.; Junlatat, J.; Sripanidkulchai, B. In Vivo and In Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Lentinus Polychrous Extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 147, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, E.S.; Oh, J.Y.; Park, H.-J. Cordyceps Militaris Extract Suppresses Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Acute Colitis in Mice and Production of Inflammatory Mediators from Macrophages and Mast Cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 134, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Formulation | Molecular Ratio | Water (% v/v) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaDES 1 | Glycerol/glycine/water | 7:1:3 | 30 |

| NaDES 2 | Glycerol/glucose | 2:1 | 30 |

| NaDES 3 | Choline chloride/ethylene glycol | 1:2 | 30 |

| NaDES 4 | Choline chloride/glycerol | 1:2 | 30 |

| Phenolic Compound | Water | NaDES 1 | Water | NaDES 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| µg/L (LDE Liquid) | µg/100 g of Dry LDE | |||

| p-Coumaric acid | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 7.2 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 80.9 ± 6.1 |

| 3,4-Dihydroxibenzoic acid | 5.07 ± 0.08 | 26.6 ± 2.3 | 56.3 ± 0.8 | 295.8 ± 26.3 |

| Gallic acid | 20.0 ± 0.2 | 36.3 ± 3.5 | 222.0 ± 2.3 | 403.6 ± 39.1 |

| 4-Hydroxibenzoic acid | 28.6 ± 0.7 | 83.0 ± 7.2 | 318.0 ± 8.5 | 922.0 ± 80.2 |

| Vanillic acid | 23.2 ± 1.2 | 2590.3 ± 23.3 | 258.3 ± 14.2 | 28,781 ± 259 |

| Rutin | 5.8 ± 0.01 | 7.8 ± 0.6 | 64.1 ± 0.1 | 87.1 ± 6.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bidooki, S.H.; Rodríguez-Martínez, B.; Quero, J.; Herrera-Marcos, L.V.; Paesa, M.; Delgado-Machuca, M.; F. Beas-Guzmán, O.; Osada, J.; Ferreira-Santos, P.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J. Lactarius deliciosus Extract from Green Microwave-Assisted Eutectic Solvent Extraction as a Therapeutic Candidate Against Colon Cancer. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121452

Bidooki SH, Rodríguez-Martínez B, Quero J, Herrera-Marcos LV, Paesa M, Delgado-Machuca M, F. Beas-Guzmán O, Osada J, Ferreira-Santos P, Rodríguez-Yoldi MJ. Lactarius deliciosus Extract from Green Microwave-Assisted Eutectic Solvent Extraction as a Therapeutic Candidate Against Colon Cancer. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121452

Chicago/Turabian StyleBidooki, Seyed Hesamoddin, Beatriz Rodríguez-Martínez, Javier Quero, Luis Vicente Herrera-Marcos, Mónica Paesa, Marina Delgado-Machuca, Oscar F. Beas-Guzmán, Jesús Osada, Pedro Ferreira-Santos, and María Jesús Rodríguez-Yoldi. 2025. "Lactarius deliciosus Extract from Green Microwave-Assisted Eutectic Solvent Extraction as a Therapeutic Candidate Against Colon Cancer" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121452

APA StyleBidooki, S. H., Rodríguez-Martínez, B., Quero, J., Herrera-Marcos, L. V., Paesa, M., Delgado-Machuca, M., F. Beas-Guzmán, O., Osada, J., Ferreira-Santos, P., & Rodríguez-Yoldi, M. J. (2025). Lactarius deliciosus Extract from Green Microwave-Assisted Eutectic Solvent Extraction as a Therapeutic Candidate Against Colon Cancer. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121452