Synergistic Genotoxic Effects of Gamma Rays and UVB Radiation on Human Blood

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Donor Recruitment and Blood Collection

2.2. Preparation of Samples and Irradiation Protocol

2.3. Dicentric Chromosome Assay

2.4. γH2AX Foci Analysis for Estimation of the DSBs and Repair

3. Results

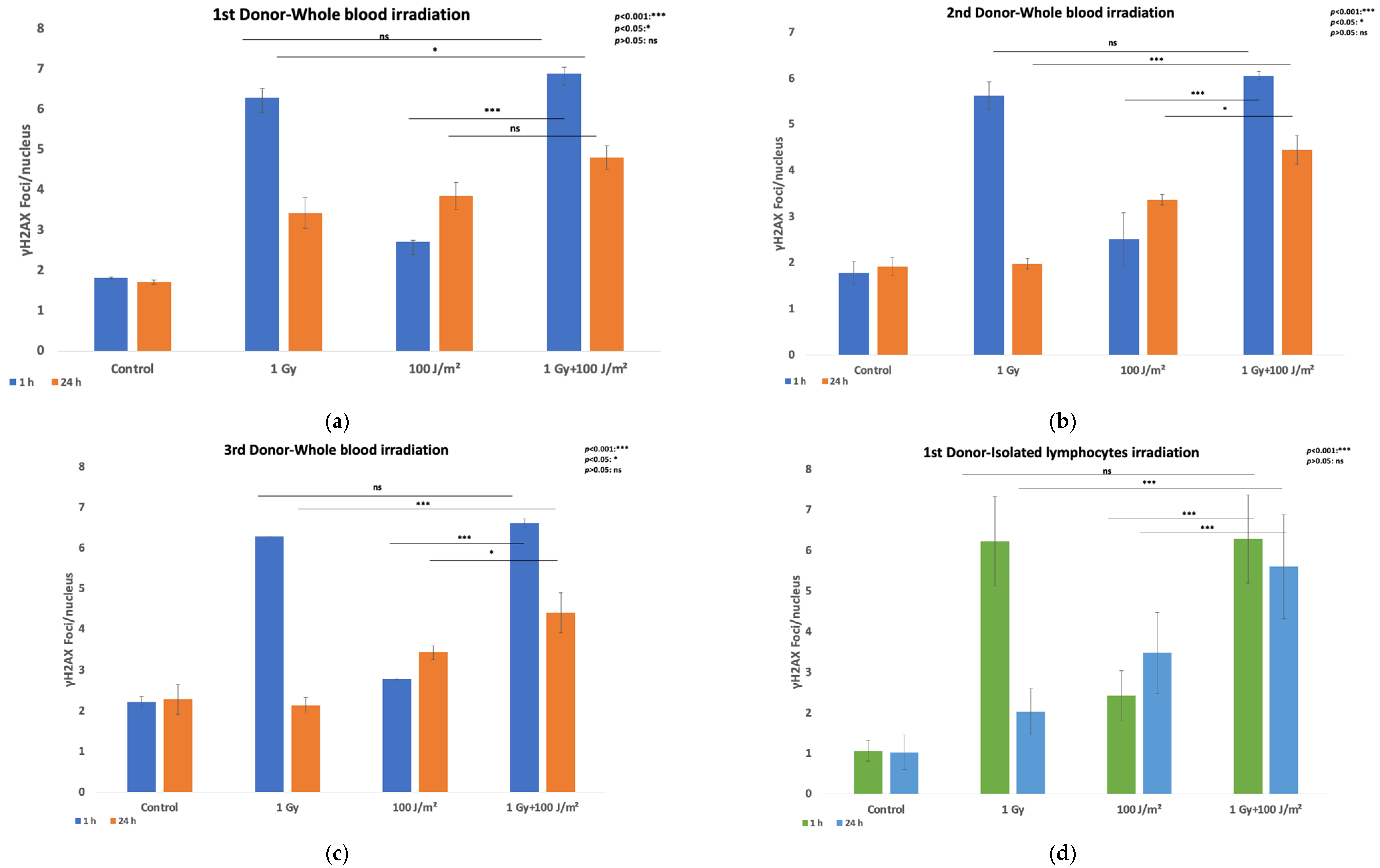

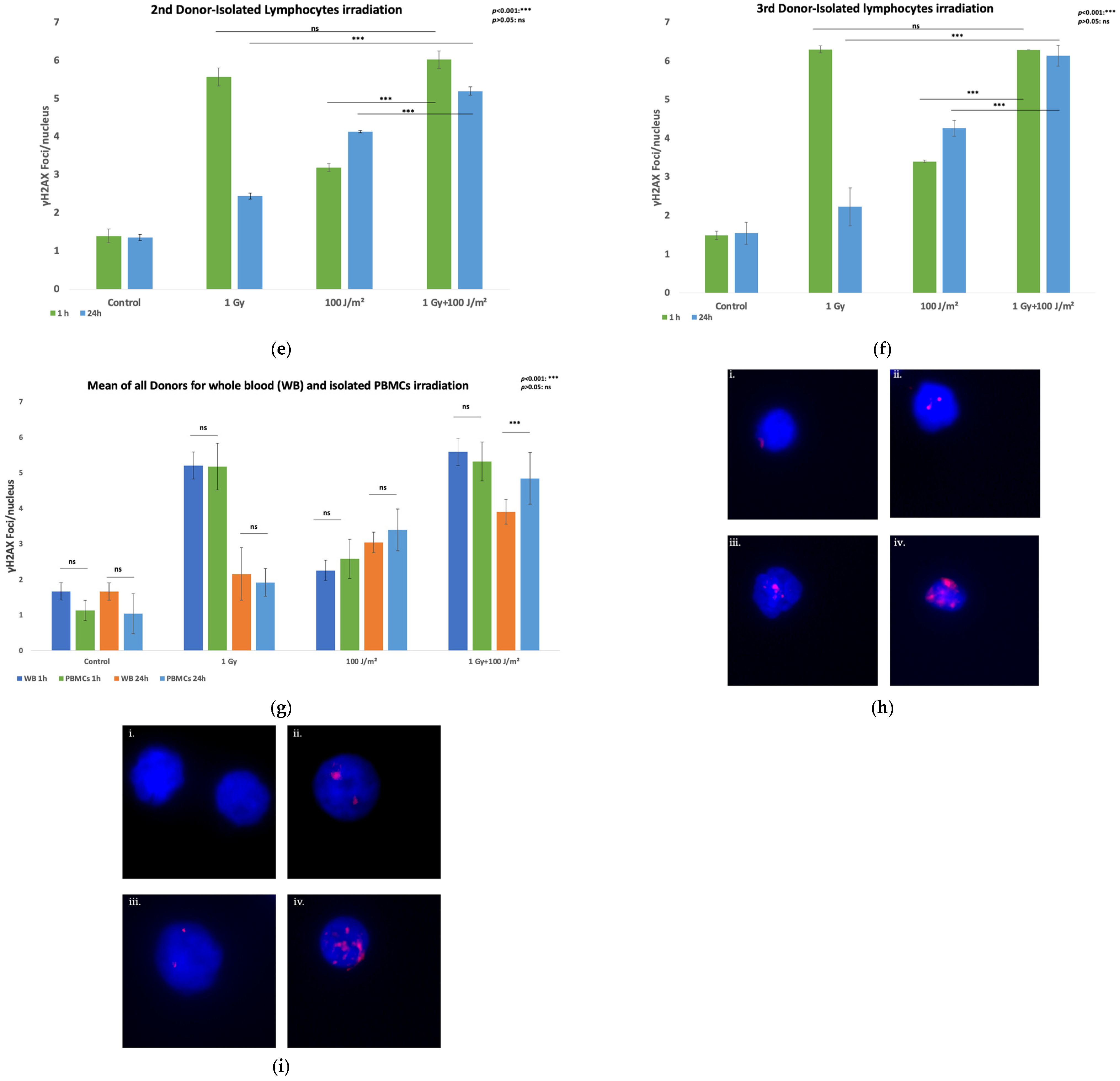

3.1. DNA Damage Measurement

3.2. Synergy Evaluation—The Bliss Independence Model

3.3. Genomic Instability-Chromosomal Aberrations Assay

3.4. Extension of the Linear-Quadratic Model to Predict Dicentric Chromosome Yield Following Co-Exposure of Whole Blood or Isolated PBMCs to Gamma and UVB Radiation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Volatier, T.; Schumacher, B.; Meshko, B.; Hadrian, K.; Cursiefen, C.; Notara, M. Short-Term UVB Irradiation Leads to Persistent DNA Damage in Limbal Epithelial Stem Cells, Partially Reversed by DNA Repairing Enzymes. Biology 2023, 12, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, R.P.; Richa; Kumar, A.; Tyagi, M.B.; Sinha, R.P. Molecular Mechanisms of Ultraviolet Radiation-Induced DNA Damage and Repair. J. Nucleic Acids 2010, 2010, 592980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickoloff, J.A.; Sharma, N.; Taylor, L. Clustered DNA Double-Strand Breaks: Biological Effects and Relevance to Cancer Radiotherapy. Genes 2020, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Boiti, A.; Vallone, D.; Foulkes, N.S. Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling and Oxidative Stress: Transcriptional Regulation and Evolution. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenova, V.; Mladenov, E.; Stuschke, M.; Iliakis, G. DNA Damage Clustering after Ionizing Radiation and Consequences in the Processing of Chromatin Breaks. Molecules 2022, 27, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavragani, I.V.; Nikitaki, Z.; Kalospyros, S.A.; Georgakilas, A.G. Ionizing Radiation and Complex DNA Damage: From Prediction to Detection Challenges and Biological Significance. Cancers 2019, 11, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkikoudi, A.; Manda, G.; Beinke, C.; Giesen, U.; Al-Qaaod, A.; Dragnea, E.-M.; Dobre, M.; Neagoe, I.V.; Sangsuwan, T.; Haghdoost, S.; et al. Synergistic Effects of UVB and Ionizing Radiation on Human Non-Malignant Cells: Implications for Ozone Depletion and Secondary Cosmic Radiation Exposure. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantelias, A.; Karachristou, I.; Georgakilas, A.G.; Terzoudi, G.I. Interphase Cytogenetic Analysis of Micronucleated and Multinucleated Cells Supports the Premature Chromosome Condensation Hypothesis as the Mechanistic Origin of Chromothripsis. Cancers 2019, 11, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremi, I.; Havaki, S.; Georgitsopoulou, S.; Terzoudi, G.; Lykakis, I.N.; Iliakis, G.; Georgakilas, V.; Gorgoulis, V.G.; Georgakilas, A.G. Biological Response of Human Cancer Cells to Ionizing Radiation in Combination with Gold Nanoparticles. Cancers 2022, 14, 5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitaki, Z.; Pariset, E.; Sudar, D.; Costes, S.V.; Georgakilas, A.G. In Situ Detection of Complex DNA Damage Using Microscopy: A Rough Road Ahead. Cancers 2020, 12, 3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samivel, R.; Pugalendi, K.; Menon, V. Modulation of UVB-induced Oxidative Stress by Ursolic Acid in Human Blood Lymphocytes. Asian J. Biochem. 2008, 3, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, X.; Gao, F.; de Groot, J.F.; Koul, D.; Yung, W.K.A. PARP-mediated PARylation of MGMT is critical to promote repair of temozolomide-induced O6-methylguanine DNA damage in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 920–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Sachsenmeier, K.; Zhang, L.; Sult, E.; Hollingsworth, R.E.; Yang, H. A New Bliss Independence Model to Analyze Drug Combination Data. SLAS Discov. 2014, 19, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S.J. The linear quadratic model: Usage, interpretation and challenges. Phys. Med. Biol. 2018, 64, 01tr01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, M.; Strausmanis, R. The repair of chromosome aberrations in human lymphocytes after combined irradiation with UV-radiation (254 nm) and X-rays. Mutat. Res. 1983, 120, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, C.V. Free-Radical-Induced DNA Damage and Its Repair; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, M.; He, X.; Liu, N.; Deng, H. Role of reactive oxygen species in ultraviolet-induced photodamage of the skin. Cell Div. 2024, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firsanov, D.V.; Solovjeva, L.V.; Svetlova, M.P. H2AX phosphorylation at the sites of DNA double-strand breaks in cultivated mammalian cells and tissues. Clin. Epigenetics 2011, 2, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda-Rivera, A.K.; Cruz-Gregorio, A.; Arancibia-Hernández, Y.L.; Hernández-Cruz, E.Y.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. RONS and Oxidative Stress: An Overview of Basic Concepts. Oxygen 2022, 2, 437–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altomare, A.; Baron, G.; Brioschi, M.; Longoni, M.; Butti, R.; Valvassori, E.; Tremoli, E.; Carini, M.; Agostoni, P.; Vistoli, G.; et al. N-Acetyl-Cysteine Regenerates Albumin Cys34 by a Thiol-Disulfide Breaking Mechanism: An Explanation of Its Extracellular Antioxidant Activity. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoryan, H.; Li, H.; Iavarone, A.T.; Williams, E.R.; Rappaport, S.M. Cys34 adducts of reactive oxygen species in human serum albumin. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012, 25, 1633–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, M.; Rondeau, P.; Singh, N.R.; Tarnus, E.; Bourdon, E. The antioxidant properties of serum albumin. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 1783–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glantzounis, G.K.; Tsimoyiannis, E.C.; Kappas, A.M.; Galaris, D.A. Uric acid and oxidative stress. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2005, 11, 4145–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, E.P.; Burini, R.C. High plasma uric acid concentration: Causes and consequences. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2012, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sautin, Y.Y.; Johnson, R.J. Uric acid: The oxidant-antioxidant paradox. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2008, 27, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraghmeh, D.N.; Karaman, R. The Redox Process in Red Blood Cells: Balancing Oxidants and Antioxidants. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, V.; Diederich, L.; Keller, T.C.S.t.; Kramer, C.M.; Lückstädt, W.; Panknin, C.; Suvorava, T.; Isakson, B.E.; Kelm, M.; Cortese-Krott, M.M. Red Blood Cell Function and Dysfunction: Redox Regulation, Nitric Oxide Metabolism, Anemia. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2017, 26, 718–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, L.H.; Conger, A.D.; Ebert, M.; Hornsey, S.; Scott, O.C. The concentration of oxygen dissolved in tissues at the time of irradiation as a factor in radiotherapy. Br. J. Radiol. 1953, 26, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, D.R.; Partridge, M. A mechanistic investigation of the oxygen fixation hypothesis and oxygen enhancement ratio. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2015, 1, 045209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, G.H.; Ren, Z.Q.; Du, B.; Shao, W.; Dong, H.J.; Du, A.C. Platelet-rich plasma protects human keratinocytes from UVB-induced apoptosis by attenuating inflammatory responses and endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H.; Huang, J.; Li, L.; Tang, J.; Cheng, B. The Anti-photoaging Effects of Pre- and Post-treatment of Platelet-rich Plasma on UVB-damaged HaCaT Keratinocytes. Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 97, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, M. Radiation Oncology Physics: A Handbook for Teachers and Students. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006, 51, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, I.M.; Chen, J. Histone H2AX is phosphorylated in an ATR-dependent manner in response to replicational stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 47759–47762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.E.; Applegate, L.A.; Ley, R.D. Excision Repair of Uvr-Induced Pyrimidine Dimers in Corneal DNA. Photochem. Photobiol. 1988, 47, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council, N.R. Health Risks from Exposure to Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation: BEIR VII Phase 2; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; p. 422. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, Y.; Yoshida, M.A.; Fujioka, K.; Kurosu, Y.; Ujiie, R.; Yanagi, A.; Tsuyama, N.; Miura, T.; Inaba, T.; Kamiya, K.; et al. Dose–response curves for analyzing of dicentric chromosomes and chromosome translocations following doses of 1000 mGy or less, based on irradiated peripheral blood samples from five healthy individuals. J. Radiat. Res. 2017, 59, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, F.A.; Akleyev, A.V.; Hauer-Jensen, M.; Hendry, J.H.; Kleiman, N.J.; Macvittie, T.J.; Aleman, B.M.; Edgar, A.B.; Mabuchi, K.; Muirhead, C.R.; et al. ICRP publication 118: ICRP statement on tissue reactions and early and late effects of radiation in normal tissues and organs–Threshold doses for tissue reactions in a radiation protection context. Ann. ICRP 2012, 41, 1–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, M.P.; Azizova, T.V.; Richardson, D.B.; Tapio, S.; Bernier, M.O.; Kreuzer, M.; Cucinotta, F.A.; Bazyka, D.; Chumak, V.; Ivanov, V.K.; et al. Ionising radiation and cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2023, 380, e072924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzer, M.; Auvinen, A.; Cardis, E.; Hall, J.; Jourdain, J.-R.; Laurier, D.; Little, M.P.; Peters, A.; Raj, K.; Russell, N.S.; et al. Low-dose ionising radiation and cardiovascular diseases—Strategies for molecular epidemiological studies in Europe. Mutat. Res./Rev. Mutat. Res. 2015, 764, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselet, B.; Rombouts, C.; Benotmane, A.M.; Baatout, S.; Aerts, A. Cardiovascular diseases related to ionizing radiation: The risk of low-dose exposure (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 38, 1623–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulhern, R.K.; Merchant, T.E.; Gajjar, A.; Reddick, W.E.; Kun, L.E. Late neurocognitive sequelae in survivors of brain tumours in childhood. Lancet Oncol. 2004, 5, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene-Schloesser, D.; Robbins, M.E. Radiation-induced cognitive impairment--from bench to bedside. Neuro Oncol. 2012, 14 (Suppl. 4), iv37–iv44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IAEA. Cytogenetic Dosimetry: Applications in Preparedness for and Response to Radiation Emergencies; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fenech, M.; Kirsch-Volders, M.; Natarajan, A.T.; Surralles, J.; Crott, J.W.; Parry, J.; Norppa, H.; Eastmond, D.A.; Tucker, J.D.; Thomas, P. Molecular mechanisms of micronucleus, nucleoplasmic bridge and nuclear bud formation in mammalian and human cells. Mutagenesis 2011, 26, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzagatti, A.; Engel, J.L.; Ly, P. Boveri and beyond: Chromothripsis and genomic instability from mitotic errors. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, M.S.; Holland, A.J. The impact of mitotic errors on cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2018, 32, 620–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadet, J.; Sage, E.; Douki, T. Ultraviolet radiation-mediated damage to cellular DNA. Mutat. Res. 2005, 571, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daya-Grosjean, L.; Sarasin, A. The role of UV induced lesions in skin carcinogenesis: An overview of oncogene and tumor suppressor gene modifications in xeroderma pigmentosum skin tumors. Mutat. Res. 2005, 571, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, P.; Goedecke, W.; Obe, G. Mechanisms of DNA double-strand break repair and their potential to induce chromosomal aberrations. Mutagenesis 2000, 15, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, R.A.; McGranahan, N.; Bartek, J.; Swanton, C. The causes and consequences of genetic heterogeneity in cancer evolution. Nature 2013, 501, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupina, K.; Goginashvili, A.; Cleveland, D.W. Causes and consequences of micronuclei. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2021, 70, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Z.; Spektor, A.; Cornils, H.; Francis, J.M.; Jackson, E.K.; Liu, S.; Meyerson, M.; Pellman, D. Chromothripsis from DNA damage in micronuclei. Nature 2015, 522, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Kumar, S.; Angdisen, J.; Datta, K.; Fornace, A.J.; Suman, S. Radiation Quality-Dependent Progressive Increase in Oxidative DNA Damage and Intestinal Tumorigenesis in Apc1638N/+ Mice. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, B.; Gómez-Cayupán, J.; Aranis, I.; García Tapia, E.; Coghlan, C.; Ulloa, M.-J.; Gelerstein Claro, S.; Urbina, K.; Espinoza, G.; De Grazia, J.; et al. Oxidative Stress-Mediated DNA Damage Induced by Ionizing Radiation in Modern Computed Tomography: Evidence for Antioxidant-Based Radioprotective Strategies. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidelines on limits of exposure to ultraviolet radiation of wavelengths between 180 nm and 400 nm (incoherent optical radiation). Health Phys. 2004, 87, 171–186. [CrossRef]

- Sliney, D.H. Radiometric quantities and units used in photobiology and photochemistry: Recommendations of the Commission Internationale de L’Eclairage (International Commission on Illumination). Photochem. Photobiol. 2007, 83, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, D.; Vale, N. Evaluation of synergism in drug combinations and reference models for future orientations in oncology. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2022, 3, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Donors | RI-1 Gy Gamma Rays | RI-1 Gy Gamma Rays + 100 J/m2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | WB: 0.45 | WB: 0.30 |

| PBMCs: 0.67 | PBMCs: 0.11 | |

| 2nd | WB: 0.66 | WB: 0.33 |

| PBMCs: 0.56 | PBMCs: 0.14 | |

| 3rd | WB: 0.65 | WB: 0.27 |

| PBMCs: 0.65 | PBMCs: 0.02 |

| Whole Blood | Isolated PBMCs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Donor | 2nd Donor | 3rd Donor | 1st Donor | 2nd Donor | 3rd Donor | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0.855 | 0.569 | 0.623 | 0.631 | 0.662 | 0.797 | |

| 0.145 | 0.431 | 0.377 | 0.369 | 0.338 | 0.203 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gkikoudi, A.; Adamopoulou, A.; Diamadaki, D.; Matsades, P.; Tzakakos, I.; Triantopoulou, S.; Vasilopoulos, S.N.; Manda, G.; Terzoudi, G.I.; Georgakilas, A.G. Synergistic Genotoxic Effects of Gamma Rays and UVB Radiation on Human Blood. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1451. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121451

Gkikoudi A, Adamopoulou A, Diamadaki D, Matsades P, Tzakakos I, Triantopoulou S, Vasilopoulos SN, Manda G, Terzoudi GI, Georgakilas AG. Synergistic Genotoxic Effects of Gamma Rays and UVB Radiation on Human Blood. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1451. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121451

Chicago/Turabian StyleGkikoudi, Angeliki, Athanasia Adamopoulou, Despoina Diamadaki, Panagiotis Matsades, Ioannis Tzakakos, Sotiria Triantopoulou, Spyridon N. Vasilopoulos, Gina Manda, Georgia I. Terzoudi, and Alexandros G. Georgakilas. 2025. "Synergistic Genotoxic Effects of Gamma Rays and UVB Radiation on Human Blood" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1451. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121451

APA StyleGkikoudi, A., Adamopoulou, A., Diamadaki, D., Matsades, P., Tzakakos, I., Triantopoulou, S., Vasilopoulos, S. N., Manda, G., Terzoudi, G. I., & Georgakilas, A. G. (2025). Synergistic Genotoxic Effects of Gamma Rays and UVB Radiation on Human Blood. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1451. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121451