The Influence of Nonlinear Pedagogy Physical Education Intervention on Cognitive Abilities in Primary School Children: A Preliminary Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

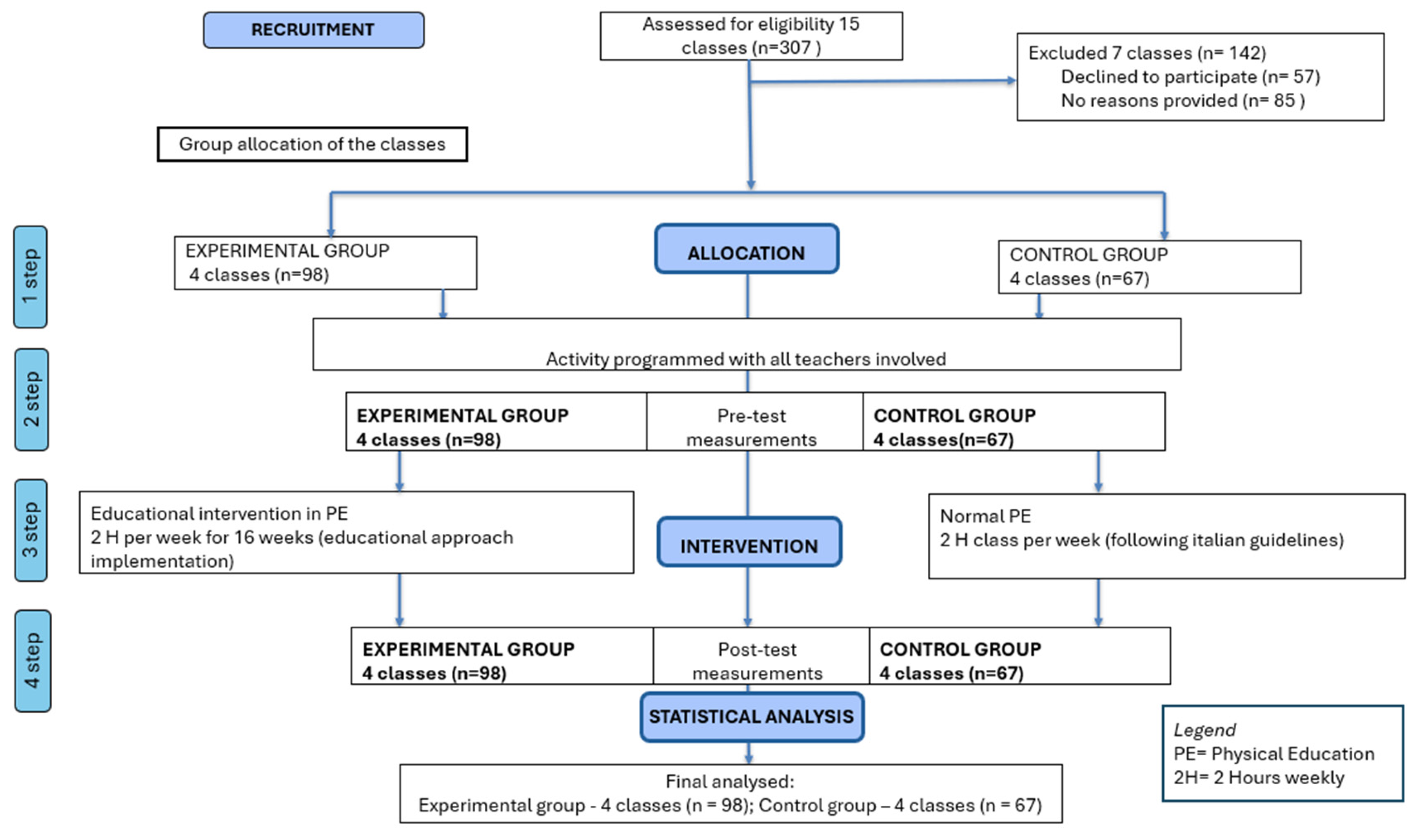

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NLP | NonLinear Pedagogy |

| PE | Physical Education |

| EG | Experimental Group |

| CG | Control Group |

| GMI | Gross Motor Index |

| DA | Divided Attention |

| HE | Hawk Eye |

References

- Cioni, G.; Sgandurra, G. Normal Psychomotor Development. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2013, 111, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Hillman, C.H.; Castelli, D.; Etnier, J.L.; Lee, S.; Tomporowski, P.; Lambourne, K.; Szabo-Reed, A.N. Physical Activity, Fitness, Cognitive Function, and Academic Achievement in Children: A Systematic Review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1197–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haibach-Beach, P.S.; Perreault, M.; Brian, A.; Collier, D.H. Motor Learning and Development; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2023; ISBN 1-7182-1171-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.A.; Lopez, A.; Ribeiro, S.M. Promoting Physical Health: Infants, Children, and Youth. In Interprofessional Perspectives for Community Practice; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2024; pp. 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright, N.; Goodway, J.; John, A.; Thomas, K.; Piper, K.; Williams, K.; Gardener, D. Developing Children’s Motor Skills in the Foundation Phase in Wales to Support Physical Literacy. Educ. 3-13 2020, 48, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N.P.; Emerson, M.J.; Witzki, A.H.; Howerter, A.; Wager, T.D. The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cognit. Psychol. 2000, 41, 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schacter, D.L. Implicit Memory, Constructive Memory, and Imagining the Future: A Career Perspective. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 14, 256–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, J.R. Effects of Physical Activity on Children’s Executive Function: Contributions of Experimental Research on Aerobic Exercise. Dev. Rev. 2010, 30, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.L.; Tomporowski, P.D.; McDowell, J.E.; Austin, B.P.; Miller, P.H.; Yanasak, N.E.; Allison, J.D.; Naglieri, J.A. Exercise Improves Executive Function and Achievement and Alters Brain Activation in Overweight Children: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Health Psychol. 2011, 30, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, F.; Benzing, V.; Conzelmann, A.; Schmidt, M. Boost Your Brain, While Having a Break! The Effects of Long-Term Cognitively Engaging Physical Activity Breaks on Children’s Executive Functions and Academic Achievement. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Feng, L.; Wang, J.; Ma, F.; Chen, J.; Qu, S.; Luo, D. Play Smart, Be Smart? Effect of Cognitively Engaging Physical Activity Interventions on Executive Function among Children 4~12 Years Old: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, N.S.; Vimalan, V.; Padmanabhan, P.; Gulyás, B. An Overview on Cognitive Function Enhancement through Physical Exercises. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tolmie, A. Associations between Gross and Fine Motor Skills, Physical Activity, Executive Function, and Academic Achievement: Longitudinal Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesce, C.; Masci, I.; Marchetti, R.; Vazou, S.; Sääkslahti, A.; Tomporowski, P.D. Deliberate Play and Preparation Jointly Benefit Motor and Cognitive Development: Mediated and Moderated Effects. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomporowski, P.D.; Davis, C.L.; Miller, P.H.; Naglieri, J.A. Exercise and Children’s Intelligence, Cognition, and Academic Achievement. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 20, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Fels, I.M.; Te Wierike, S.C.; Hartman, E.; Elferink-Gemser, M.T.; Smith, J.; Visscher, C. The Relationship between Motor Skills and Cognitive Skills in 4–16 Year Old Typically Developing Children: A Systematic Review. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2015, 18, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.Y.; Davids, K.; Button, C.; Shuttleworth, R.; Renshaw, I.; Araújo, D. The Role of Nonlinear Pedagogy in Physical Education. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007, 77, 251–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, V.; Carvalho, J.; Araújo, D.; Pereira, E.; Davids, K. Principles of Nonlinear Pedagogy in Sport Practice. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2019, 24, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komar, J.; Chow, J.Y.; Kawabata, M.; Choo, C.Z.Y. Information and Communication Technology as an Enabler for Implementing Nonlinear Pedagogy in Physical Education: Effects on Students’ Exploration and Motivation. Asian J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2022, 2, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Song, M.; Chen, X.; Li, M.; Wang, X. The Influence of Linear and Nonlinear Pedagogy on Motor Skill Performance: The Moderating Role of Adaptability. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1540821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NaeimAbadi, Z.; Bagheri, S. The Effect of Non-Linear Pedagogy of Hurdle on Physical Literacy of Qom City Female Students. J. Mot. Control Learn. 2024, 6, e157154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, D.M.; Harrison, C.B.; Millar, S.-K.; Walters, S. The Impact of a Nonlinear Pedagogical Approach to Primary School Physical Education Upon Children’s Movement Skill Competence. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2022, 42, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.Y. Nonlinear Learning Underpinning Pedagogy: Evidence, Challenges, and Implications. Quest 2013, 65, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.Y.; Davids, K.; Button, C.; Renshaw, I. Nonlinear Pedagogy in Skill Acquisition: An Introduction; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kaloka, P.T.; Nopembri, S.; Yudanto, Y.; Elumalai, G. Improvement of Executive Function Through Cognitively Challenging Physical Activity with Nonlinear Pedagogy in Elementary Schools. Retos 2024, 51, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, J.R.; O’Callaghan, L.; Williams, J. Physical Education Pedagogies Built upon Theories of Movement Learning: How Can Environmental Constraints Be Manipulated to Improve Children’s Executive Function and Self-Regulation Skills? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahnert, J.; Schneider, W.; Bös, K. Developmental Changes and Individual Stability of Motor Abilities from the Preschool Period to Young Adulthood. In Human Development from Early Childhood to Early Adulthood; Psychology Press: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; pp. 45–72. [Google Scholar]

- Coppola, S.; D’Anna, C.; Minghelli, V.; Vastola, R. Ecological Dynamics Approach in Physical Education to Promote Cognitive Skills Development: A Review. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2024, 19, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piek, J.P.; Dyck, M.J.; Nieman, A.; Anderson, M.; Hay, D.; Smith, L.M.; McCoy, M.; Hallmayer, J. The Relationship between Motor Coordination, Executive Functioning and Attention in School Aged Children. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2004, 19, 1063–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magistro, D.; Cooper, S.B.; Carlevaro, F.; Marchetti, I.; Magno, F.; Bardaglio, G.; Musella, G. Two Years of Physically Active Mathematics Lessons Enhance Cognitive Function and Gross Motor Skills in Primary School Children. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 63, 102254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive Functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, A.; Lee, K. Interventions Shown to Aid Executive Function Development in Children 4 to 12 Years Old. Science 2011, 333, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesce, C.; Ben-Soussan, T.D. “Cogito Ergo Sum” or “Ambulo Ergo Sum”? New Perspectives in Developmental Exercise and Cognition Research; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bortoli, L.; Robazza, C. L’apprendimento Delle Abilità Motorie. Due Approcci Tra Confronto E Integrazione SDS-Riv. Cult. Sport. 2016, 109, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Button, C.; Seifert, L.; Chow, J.Y.; Araújo, D.; Davids, K. Dynamics of Skill Acquisition: An Ecological Dynamics Approach; Human Kinetics Publishers: Champaign, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Colella, D. Physical Literacy e Stili d’insegnamento. Ri-Orientare l’educazione Fisica a Scuola. Form. Insegn. 2018, 16, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Pugliese, E.; Forte, P.; D’Anna, C. Cognitive vs Ecological Dynamic Approach: A Synthetical Framework to Guide Effective Educational Choices. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2023, 23, 2480–2485. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Kelso, J.S. Dynamic Patterns: The Self-Organization of Brain and Behavior; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995; ISBN 0-262-61131-7. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, D.; Davids, K.; Renshaw, I. Cognition, Emotion and Action in Sport: An Ecological Dynamics Perspective. In Handbook of Sport Psychology; Tenenbaum, G., Eklund, R.C., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 535–555. ISBN 978-1-119-56812-4. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, K.M. Constraints on the Development of Coordination. Mot. Dev. Child. Asp. Coord. Control 1986, 341. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, J.Y.; Teo-Koh, S.M.; Tan, C.W.K.; Button, C.; Tan, B.S.-J.; Kapur, M.; Meerhoff, R.; Choo, C.Z.Y. Nonlinear Pedagogy and Its Relevance for the New PE Curriculum; Office of Education Research, National Institute of Education: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, J.Y.; Atencio, M. Complex and Nonlinear Pedagogy and the Implications for Physical Education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2014, 19, 1034–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesce, C.; Croce, R.; Ben-Soussan, T.D.; Vazou, S.; McCullick, B.; Tomporowski, P.D.; Horvat, M. Variability of Practice as an Interface between Motor and Cognitive Development. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2019, 17, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesce, C.; Marchetti, R.; Motta, A.; Bellucci, M. Joy of Moving. In MoviMenti con ImmaginAzione. Giocare con la Variabilità per Promuovere lo Sviluppo Motorio, Cognitivo e del Cittadino. [Joy of Moving. MindMovers & ImmaginAction–Playing with Variability to Promote Motor, Cognitive and Citizenship Development]; Calzetti-Mariucci: Perugia, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hopewell, S.; Chan, A.-W.; Collins, G.S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Tunn, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Berkwits, M.; Berlin, J.A. CONSORT 2025 Statement: Updated Guideline for Reporting Randomised Trials. Lancet 2025, 405, 1633–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MIUR. Indicazioni Nazionali per Il Curricolo Della Scuola Dell’infanzia e Del Primo Ciclo d’istruzione; Ministero dell’Istruzione: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- MIUR. Nota Miur n. 2915/2016—Prime Indicazioni per la Progettazione delle Attività di Formazione Destinate al Personale Scolastico; MIUR: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, A.T.; Petosa, R.; Pate, R.R. Validation of an Instrument for Measurement of Physical Activity in Youth. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1997, 29, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magistro, D.; Piumatti, G.; Carlevaro, F.; Sherar, L.B.; Esliger, D.W.; Bardaglio, G.; Magno, F.; Zecca, M.; Musella, G. Measurement Invariance of TGMD-3 in Children with and without Mental and Behavioral Disorders. Psychol. Assess. 2018, 30, 1421–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, D.; D’Anna, C.; Carlevaro, F.; Magno, F.; Magistro, D. TGMD-3. Test per la Valutazione dello Sviluppo Grosso-Motorio; Edizioni Centro Studi Erickson SpA: Trento, Italy, 2023; ISBN 88-590-3251-2. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, G.W.M.; Cooper, S.; Carlevaro, F.; Magno, F.; Boat, R.; Vagnetti, R.; D’Anna, C.; Musella, G.; Magistro, D. Normative Percentile Values for the TGMD-3 for Italian Children Aged 3–11 + Years. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2025, 28, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magistro, D.; Piumatti, G.; Carlevaro, F.; Sherar, L.B.; Esliger, D.W.; Bardaglio, G.; Magno, F.; Zecca, M.; Musella, G. Psychometric Proprieties of the Test of Gross Motor Development–Third Edition in a Large Sample of Italian Children. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Executive Functions Training|Microgate. Available online: https://training.microgate.it/en/solutions/executive-functions-training (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Derzon, J.H.; Sale, E.; Springer, J.F.; Brounstein, P. Estimating Intervention Effectiveness: Synthetic Projection of Field Evaluation Results. J. Prim. Prev. 2005, 26, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; ISBN 0-203-77158-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, W.; Marshall, S.; Batterham, A.; Hanin, J. Progressive Statistics for Studies in Sports Medicine and Exercise Science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. On the Adaptive Control of the False Discovery Rate in Multiple Testing with Independent Statistics. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2000, 25, 60–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, M.; Pournara, I.; Pontifex, M.B.; Venetsanou, F.; Pesce, C.; Vazou, S. A Meta-Analysis of Physical Activity Interventions Targeting Executive Functions in Children: Focus on Cognitive and/or Metabolic Demands? Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, P.; Pugliese, E.; Matrisciano, C.; D’Anna, C. Exploring the Relationship Between Visual-Spatial Working Memory and Gross Motor Skills in Primary School Children. Ital. J. Health Educ. Sport Incl. Didact. 2025, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovecchio, N.; Pittaluga, E. Educational Content to Improve Cognitive Function: Relationship between Physical Education and Attention Contenuti Didattici Finalizzati al Miglioramento Delle Funzioni Cognitive: Tra Educazione Fisica e Attenzione. J. Homepage 2024, 17, 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Matrisciano, C.; Minino, R.; Mariani, A.M.; D’Anna, C. The Effect of Physical Activity on Executive Functions in the Elderly Population: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, E.; Bashir, M.; Forte, P.; D’Anna, C. Effects of Physical Education and Physical Activity on Learning Ability and Emotional Intelligence in Children: A Review. Ital. J. Health Educ. SPORT Incl. Didact. 2024, 8, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Daly-Smith, A.J.; Zwolinsky, S.; McKenna, J.; Tomporowski, P.D.; Defeyter, M.A.; Manley, A. Systematic Review of Acute Physically Active Learning and Classroom Movement Breaks on Children’s Physical Activity, Cognition, Academic Performance and Classroom Behaviour: Understanding Critical Design Features. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2018, 4, e000341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, E.; van Steen, T.; Direito, A.; Stamatakis, E. Physically Active Lessons in Schools and Their Impact on Physical Activity, Educational, Health and Cognition Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 826–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.S.; Saliasi, E.; van den Berg, V.; Uijtdewilligen, L.; de Groot, R.H.M.; Jolles, J.; Andersen, L.B.; Bailey, R.; Chang, Y.-K.; Diamond, A.; et al. Effects of Physical Activity Interventions on Cognitive and Academic Performance in Children and Adolescents: A Novel Combination of a Systematic Review and Recommendations from an Expert Panel. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.; Timperio, A.; Brown, H.; Best, K.; Hesketh, K.D. Effect of Classroom-Based Physical Activity Interventions on Academic and Physical Activity Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, C.H.; Pontifex, M.B.; Castelli, D.M.; Khan, N.A.; Raine, L.B.; Scudder, M.R.; Drollette, E.S.; Moore, R.D.; Wu, C.-T.; Kamijo, K. Effects of the FITKids Randomized Controlled Trial on Executive Control and Brain Function. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e1063–e1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamijo, K.; Pontifex, M.B.; O’Leary, K.C.; Scudder, M.R.; Wu, C.-T.; Castelli, D.M.; Hillman, C.H. The Effects of an Afterschool Physical Activity Program on Working Memory in Preadolescent Children. Dev. Sci. 2011, 14, 1046–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Osorio, F.; Campos-Jara, C.; Martínez-Salazar, C.; Chirosa-Ríos, L.; Martínez-García, D. Effects of Sport-Based Interventions on Children’s Executive Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, P.; Pugliese, E.; Aquino, G.; Matrisciano, C.; Carlevaro, F.; Magno, F.; Magistro, D.; D’Anna, C. Enhancing Visuospatial Working Memory and Motor Skills Through School-Based Coordination Training. Sports 2025, 13, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive Functions. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 173, pp. 225–240. ISBN 0072-9752. [Google Scholar]

- Davids, K.; Button, C.; Bennett, S. Dynamics of Skill Acquisition: A Constraints-Led Approach.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2008; ISBN 0-7360-3686-5. [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw, I.; Davids, K.; Newcombe, D.; Roberts, W. The Constraints-Led Approach: Principles for Sports Coaching and Practice Design; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; ISBN 1-315-10235-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sannicandro, I.; Colella, D. Dall’approccio Ecologico Dinamico Alla Flessibilità Degli Apprendimenti Nella Formazione Motoria e Sportiva Del Giovane Atleta. Form. Insegn. 2025, 21, 146–152. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Control Group (CG) | Experimental Group (EG) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 67 | 98 | — |

| Age, years (M ± SD) | 7.28 ± 1.02 | 7.31 ± 0.94 | 0.842 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.611 | ||

| Male | 28 (42%) | 44 (45%) | |

| Female | 39 (58%) | 54 (55%) | |

| Extracurricular PA hours/week (M ± SD) | 2.71 ± 1.52 | 2.96 ± 2.18 | 0.398 |

| School-based PE hours/week | 2.0 for all children | 2.0 for all children | — |

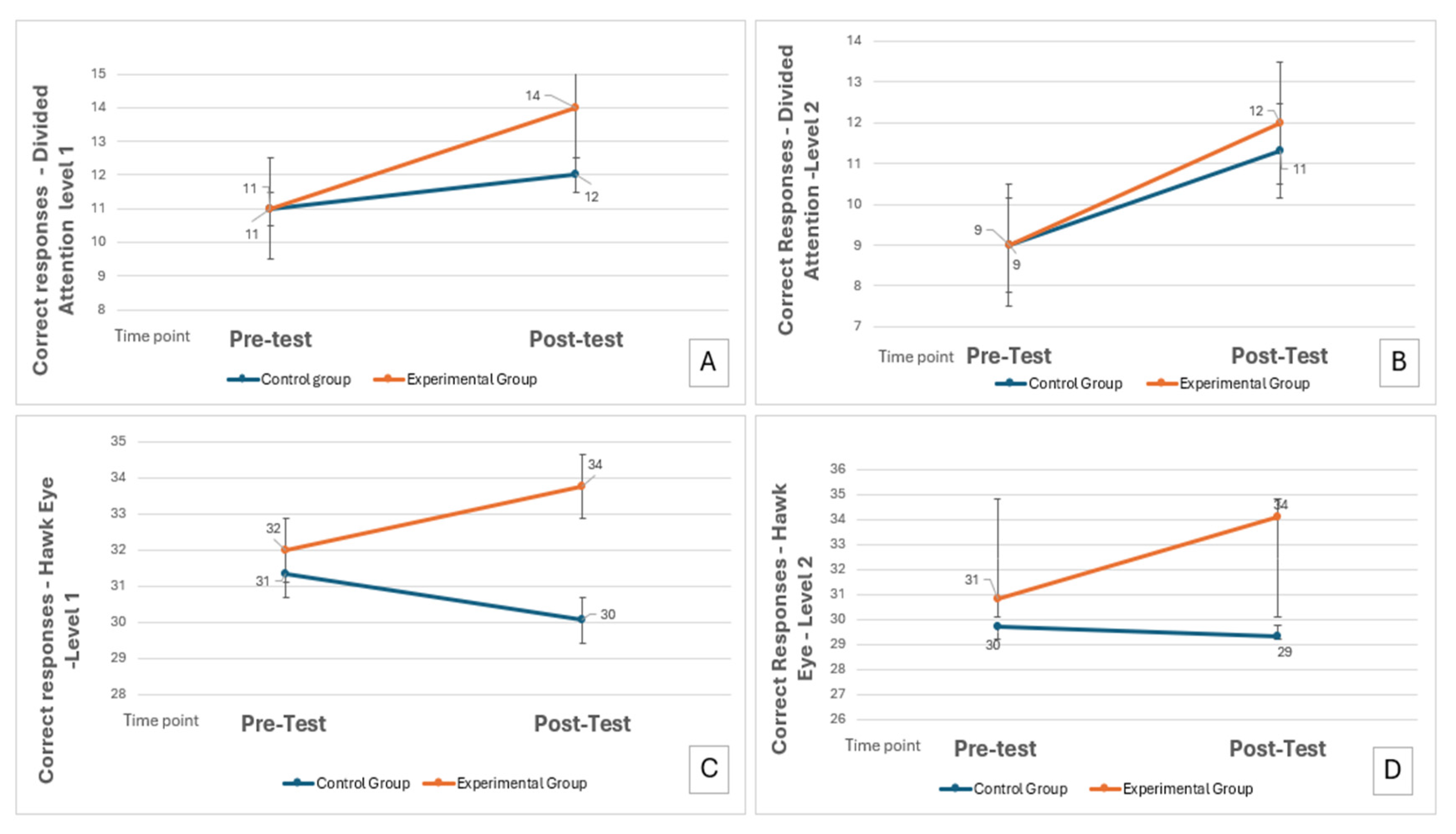

| Test | Group Type | Pre-Test | Post-Test | Main Effect Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) | Analysis of Covariance | ||

| Divided Attention Level 1 | Control Group | 11.6 | 1.3 | 12.2 | 0.75 | 0.58 | F (1161) = 6219, p = 0.014 (pFDR = 0.014) |

| Experimental Group | 11.6 | 1.7 | 13.1 | 1.15 | |||

| Diveded Attention Level 2 | Control Group | 9.3 | 2.01 | 11.2 | 0.95 | 0.42 | F (1162) = 6188, p = 0.014 (pFDR = 0.014) |

| Experimental Group | 9.2 | 2.2 | 11.9 | 1.08 | |||

| Hawk Eye Level 1 | Control Group | 31.3 | 2.8 | 29.9 | 1.9 | 0.88 | F (1162) = 21,432, p < 0.001 (pFDR = 0.002) |

| Experimental Group | 32.4 | 3.2 | 33.7 | 2.03 | |||

| Hawk Eye Level 2 | Control Group | 29.7 | 2.9 | 29.3 | 2.4 | 1.11 | F (1162) = 28,554, p < 0.001 (pFDR = 0.002) |

| Experimental Group | 30.8 | 3.02 | 33.7 | 1.6 | |||

| Test | F (1, df2) | p | η2ₚ | d | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Divided Attention L1 | 6.219 (1, 161) | 0.014 | 0.04 | 0.58 | Medium |

| Divided Attention L2 | 6.188 (1, 162) | 0.014 | 0.04 | 0.42 | Small–Medium |

| Hawk Eye L1 | 21.432 (1, 162) | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.88 | Large |

| Hawk Eye L2 | 28.554 (1, 162) | <0.001 | 0.15 | 1.11 | Large–Very Large |

| Outcome | Group | Pre-Test M (SD) | Post-Test M (SD) | Δ Mean (SD) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Divided Attention Level 1 | Control | 11.6 (1.3) | 12.2 (0.75) | +0.6 (1.1) | Small improvement |

| Experimental | 11.6 (1.7) | 13.1 (1.15) | +1.5 (1.3) | Moderate improvement | |

| Divided Attention Level 2 | Control | 9.3 (2.01) | 11.2 (0.95) | +1.9 (1.1) | Moderate improvement |

| Experimental | 9.2 (2.2) | 11.9 (1.08) | +2.7 (1.4) | Greater improvement | |

| Hawk Eye Level 1 | Control | 31.3 (2.8) | 29.9 (1.9) | −1.4 (1.2) | Decline |

| Experimental | 32.4 (3.2) | 33.7 (2.03) | +1.3 (1.5) | Improvement | |

| Hawk Eye Level 2 | Control | 29.7 (2.9) | 29.3 (2.4) | −0.4 (1.0) | No change |

| Experimental | 30.8 (3.02) | 33.7 (1.6) | +2.9 (1.5) | Strong improvement |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pugliese, E.; Forte, P.; Matrisciano, C.; Carlevaro, F.; D’Anna, C.; Magistro, D. The Influence of Nonlinear Pedagogy Physical Education Intervention on Cognitive Abilities in Primary School Children: A Preliminary Study. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121283

Pugliese E, Forte P, Matrisciano C, Carlevaro F, D’Anna C, Magistro D. The Influence of Nonlinear Pedagogy Physical Education Intervention on Cognitive Abilities in Primary School Children: A Preliminary Study. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121283

Chicago/Turabian StylePugliese, Elisa, Pasqualina Forte, Carmela Matrisciano, Fabio Carlevaro, Cristiana D’Anna, and Daniele Magistro. 2025. "The Influence of Nonlinear Pedagogy Physical Education Intervention on Cognitive Abilities in Primary School Children: A Preliminary Study" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121283

APA StylePugliese, E., Forte, P., Matrisciano, C., Carlevaro, F., D’Anna, C., & Magistro, D. (2025). The Influence of Nonlinear Pedagogy Physical Education Intervention on Cognitive Abilities in Primary School Children: A Preliminary Study. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121283