Effect of Moving Tactile Stimuli to Sole on Body Sway During Quiet Stance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

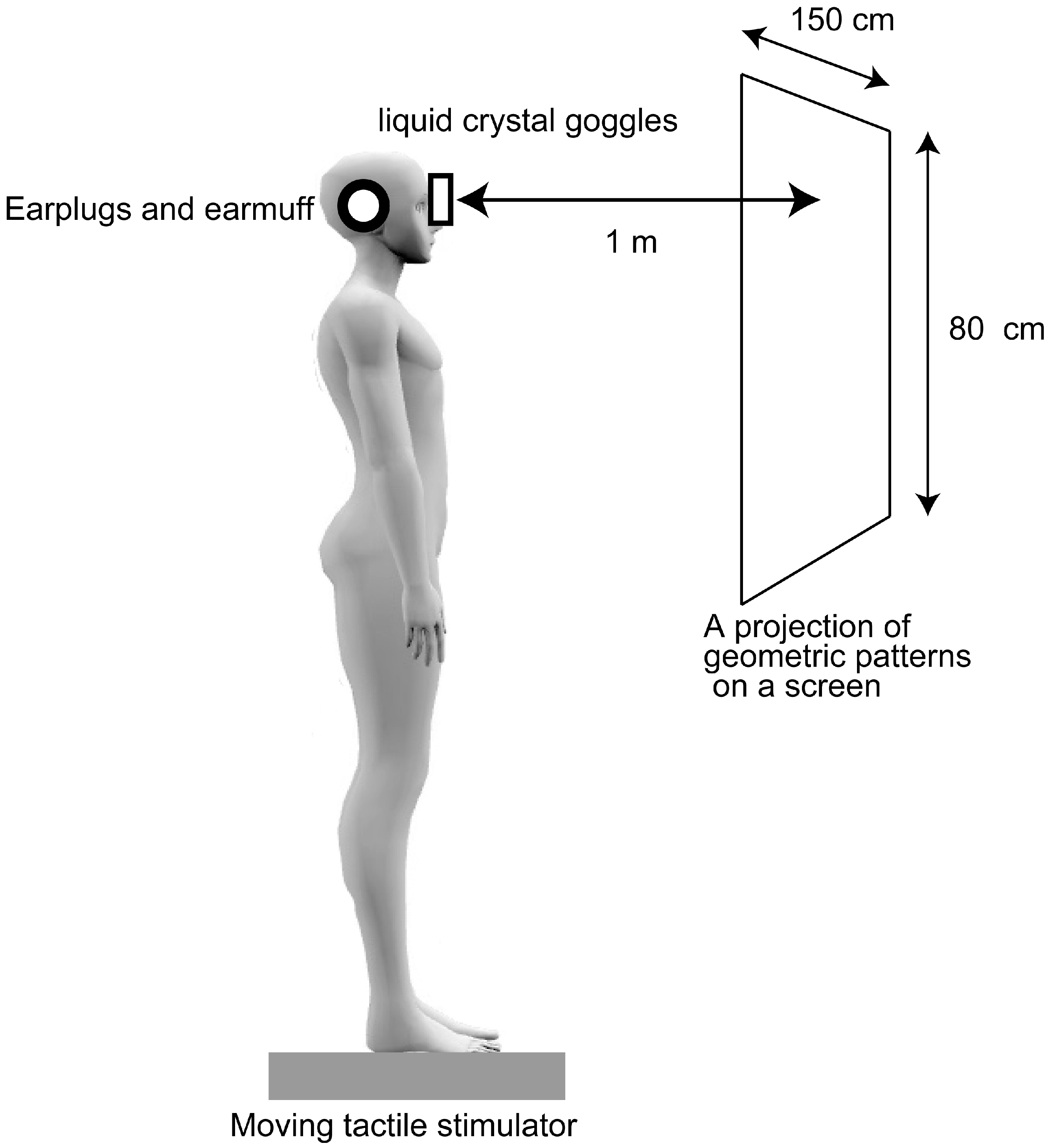

2.2. Apparatus

2.3. Procedure

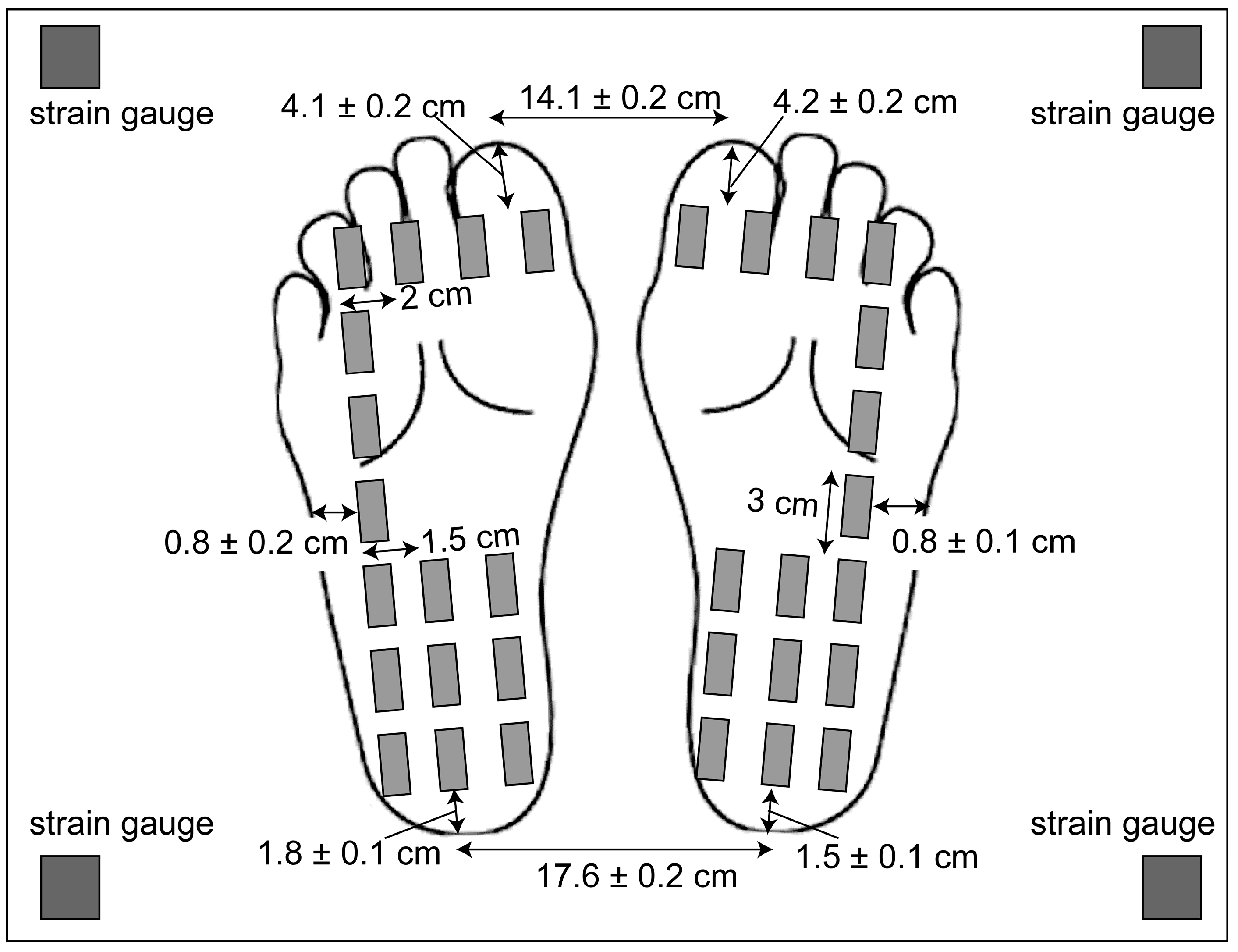

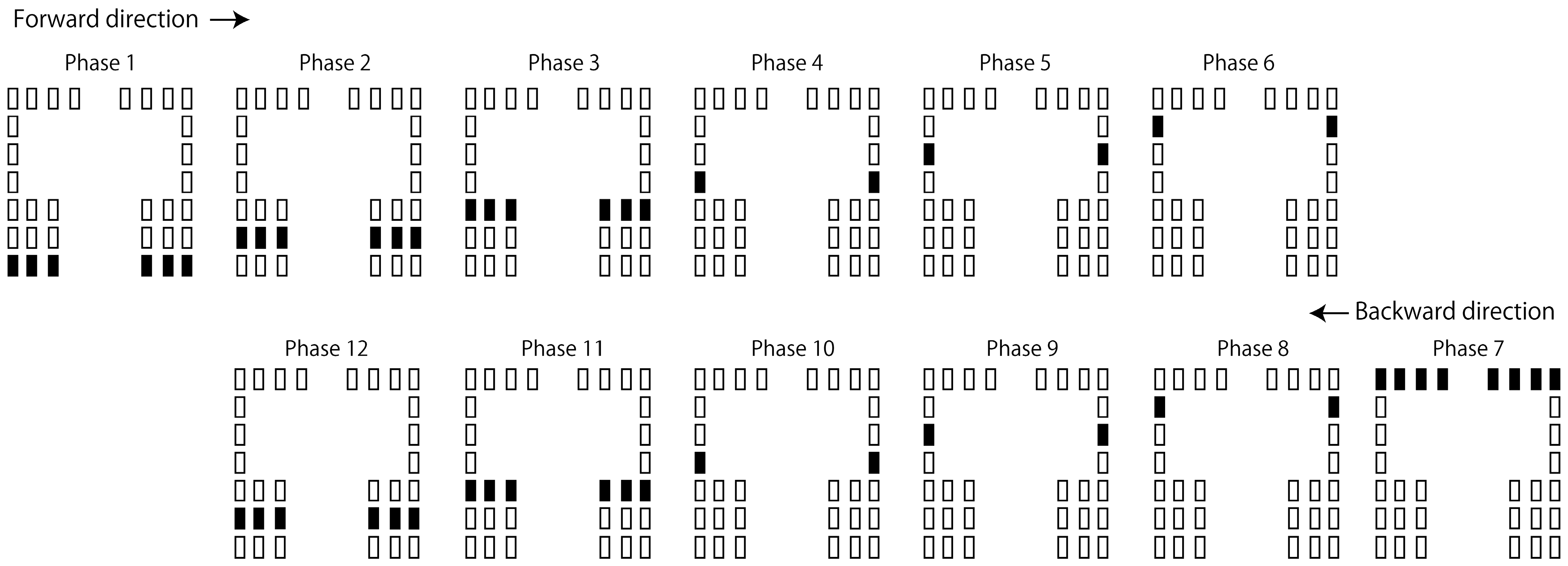

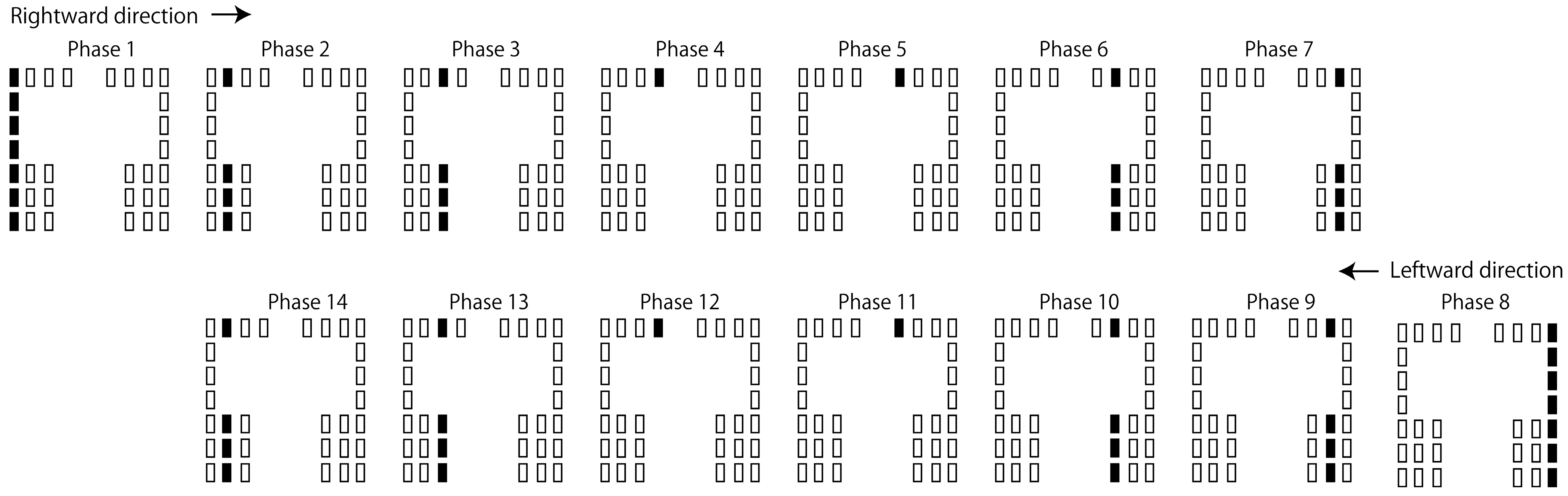

2.4. Moving Tactile Stimuli

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

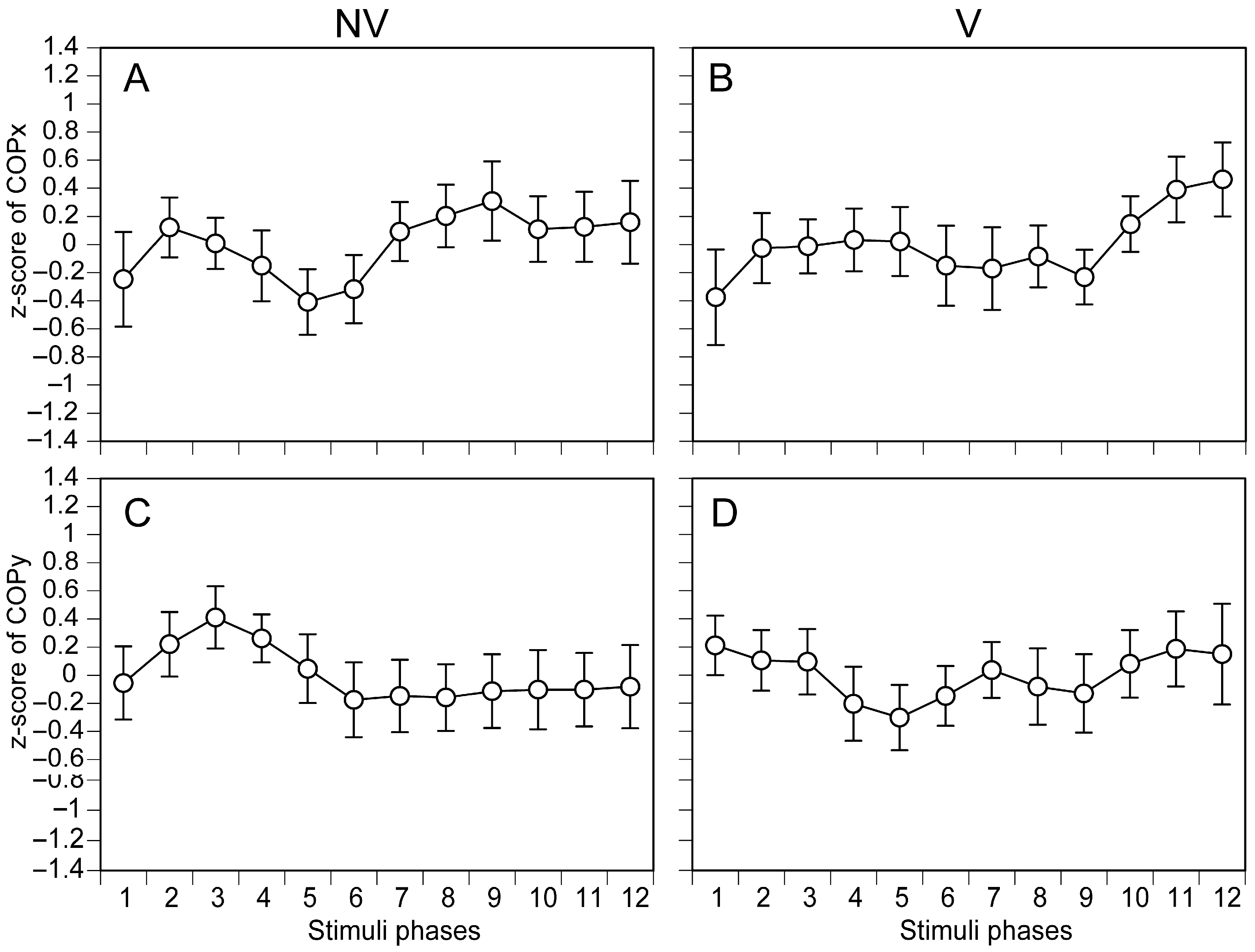

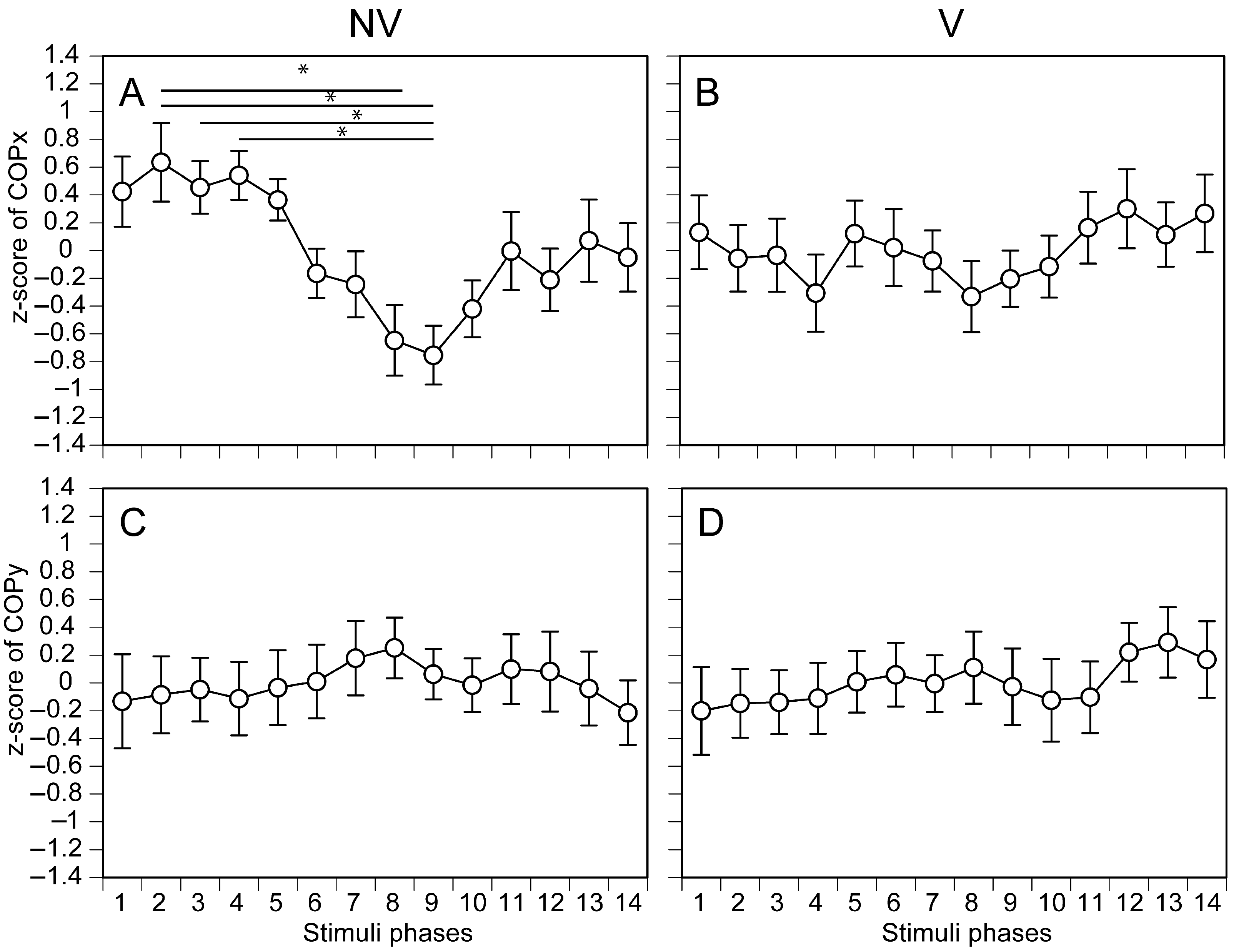

3.1. COP in Each Phase of Moving Tactile Stimuli

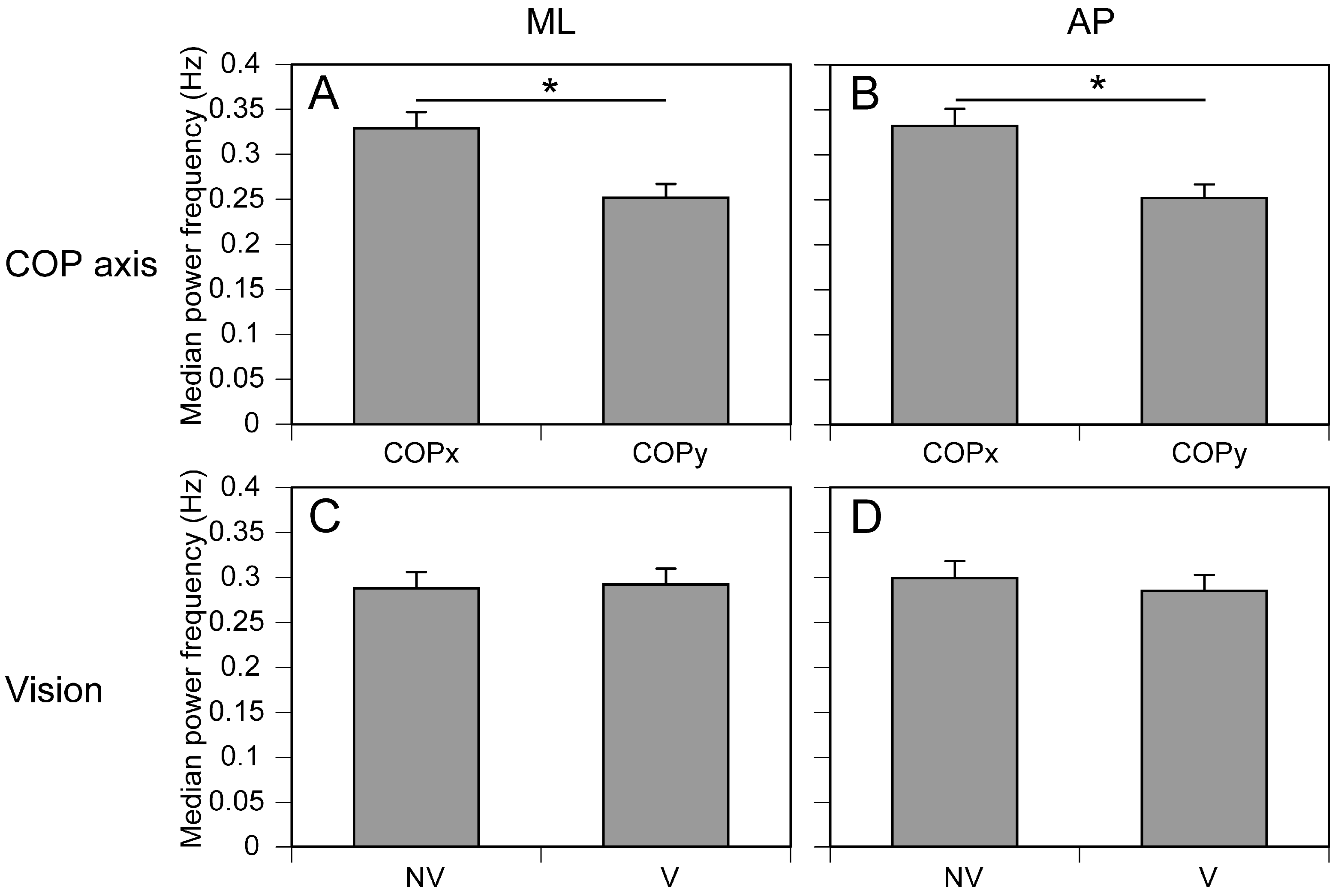

3.2. Frequency of COP Displacement

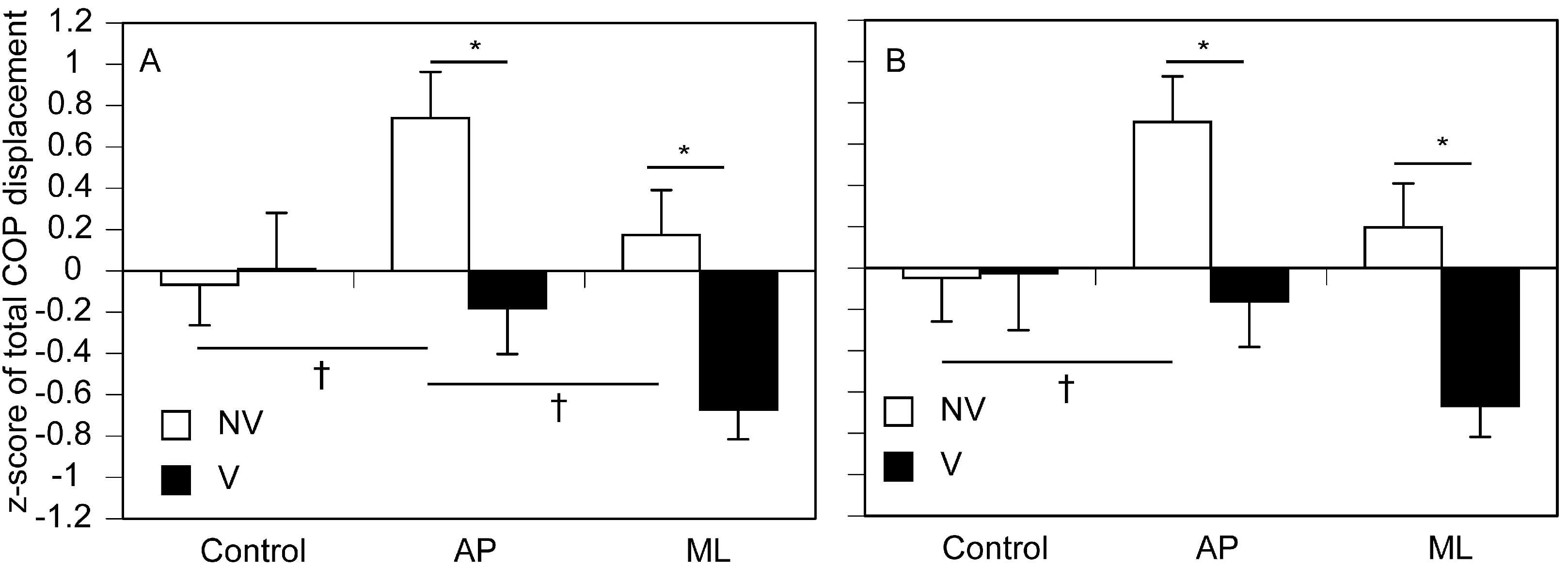

3.3. Total COP Displacement

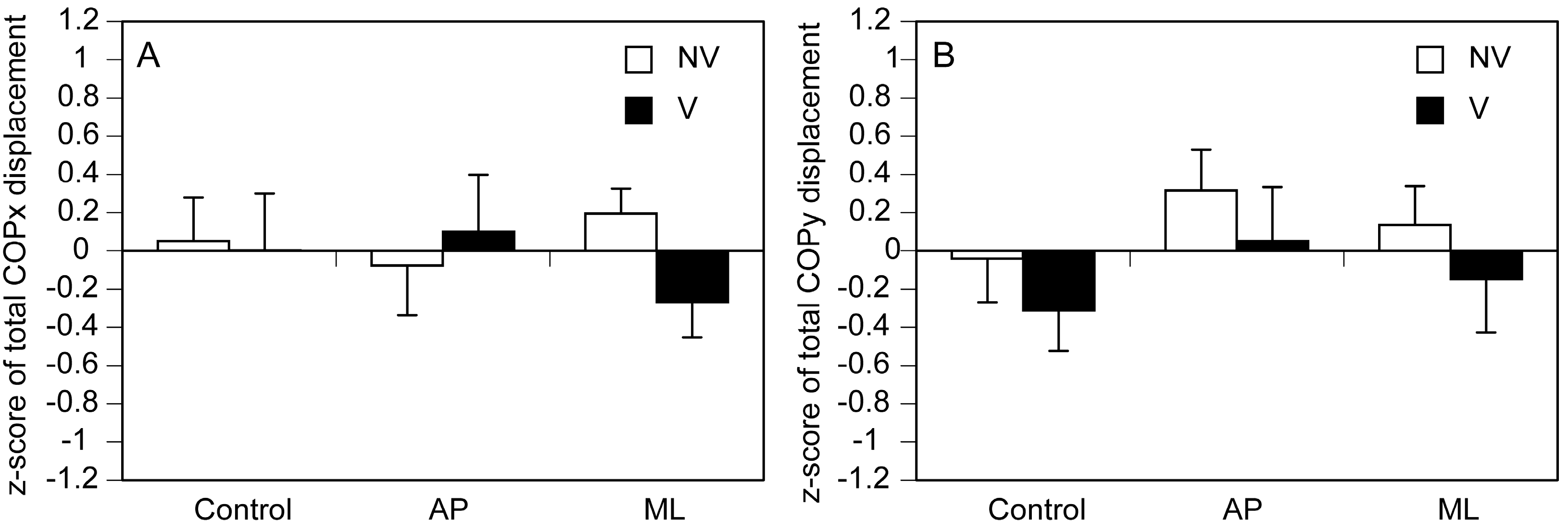

3.4. Mean COP

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Findings

4.2. Phase-Dependent COP Changes

4.3. Intermodal Reweighting

4.4. Mean COP

4.5. Limitations

4.6. Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chiba, R.; Takakusaki, K.; Ota, J.; Yozu, A.; Haga, N. Human upright posture control models based on multisensory inputs; in fast and slow dynamics. Neurosci. Res. 2016, 104, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viseux, F.; Lemaire, A.; Barbier, F.; Charpentier, P.; Leteneur, S.; Villeneuve, P. How can the stimulation of plantar cutaneous receptors improve postural control? Review and clinical commentary. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2019, 49, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, S.D. Evaluation of age-related plantar-surface insensitivity and onset age of advanced insensitivity in older adults using vibratory and touch sensation tests. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 392, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitre, J.; Paillard, T. Influence of the Plantar Cutaneous Information in Postural Regulation Depending on the Age and the Physical Activity Status. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, P.F.; Oddsson, L.I.; De Luca, C.J. The role of plantar cutaneous sensation in unperturbed stance. Exp. Brain Res. 2004, 156, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.Y.; Lin, S.I. Sensitivity of plantar cutaneous sensation and postural stability. Clin. Biomech. 2008, 23, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcot, K.; Allet, L.; Golay, A.; Hoffmeyer, P.; Armand, S. Investigation of standing balance in diabetic patients with and without peripheral neuropathy using accelerometers. Clin. Biomech. 2009, 24, 716–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaguchi, Y.; Kawasaki, T.; Oda, H.; Kunimura, H.; Hiraoka, K. Contribution of vision and tactile sensation on body sway during quiet stance. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2022, 34, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauzier, L.; Kadri, M.A.; Bouchard, E.; Bouchard, K.; Gaboury, S.; Gagnon, J.M.; Girard, M.P.; Larouche, A.; Robert, R.; Lapointe, P.; et al. Vibration of the whole foot soles surface using an inexpensive portable device to investigate age-related alterations of postural control. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 719502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.C.; Bensmaia, S.J. The neural basis of tactile motion perception. J. Neurophysiol. 2014, 112, 3023–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amemiya, T.; Beck, B.; Walsh, V.; Gomi, H.; Haggard, P. Visual area V5/hMT+ contributes to perception of tactile motion direction: A TMS study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremmer, F.; Schlack, A.; Shah, N.J.; Zafiris, O.; Kubischik, M.; Hoffmann, K.P.; Fink, G.R. Polymodal motion processing in posterior parietal and premotor cortex: A human fMRI study strongly implies equivalencies between humans and monkeys. Neuron 2001, 29, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, M.C.; Franzén, O.; McGlone, F.; Essick, G.; Dancer, C.; Pardo, J.V. Tactile motion activates the human middle temporal/V5 (MT/V5) complex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2002, 16, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, I.R.; Francis, S.T.; Bowtell, R.W.; McGlone, F.P.; Clemence, M. A functional-magnetic-resonance-imaging investigation of cortical activation from moving vibrotactile stimuli on the fingertip. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2009, 125, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacker, E.; Spitzer, B.; Lützkendorf, R.; Bernarding, J.; Blankenburg, F. Tactile motion and pattern processing assessed with high-field FMRI. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kemenade, B.M.; Seymour, K.; Wacker, E.; Spitzer, B.; Blankenburg, F.; Sterzer, P. Tactile and visual motion direction processing in hMT+/V5. Neuroimage 2014, 84, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaguchi, Y.; Kawasaki, T.; Hiraoka, K. Effect of Moving Tactile Stimuli to Mimic Altered Weight Distribution During Gait on Quiet Stance Body Sway. Percept. Mot. Skills 2023, 130, 2547–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamill, P.V.; Drizd, T.A.; Johnson, C.L.; Reed, R.B.; Roche, A.F. NCHS Growth Curves for Children Birth-18 Years; Department of Health Education and Welfare: Washington, DC, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.R.; French, K.E. Gender differences across age in motor performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 260–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribble, P.A.; Robinson, R.H.; Hertel, J.; Denegar, C.R. The effects of gender and fatigue on dynamic postural control. J. Sport Rehabil. 2009, 18, 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahraman, B.O.; Kahraman, T.; Kalemci, O.; Sengul, Y.S. Gender differences in postural control in people with nonspecific chronic low back pain. Gait Posture 2018, 64, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, L.J.; Bryden, M.P.; Bulman-Fleming, M.B. Footedness is a better predictor than is handedness of emotional lateralization. Neuropsychologia 1998, 36, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zverev, Y.P. Spatial parameters of walking gait and footedness. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2006, 33, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunimura, H.; Oda, H.; Kawasaki, T.; Tsujinaka, R.; Hamada, N.; Fukuda, S.; Matsuoka, M.; Hiraoka, K. Effect of Laterally Moving Tactile Stimuli to Sole on Anticipatory Postural Adjustment of Gait Initiation in Healthy Males. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, W.H.; Darian-Smith, I.; Kornhuber, H.H.; Mountcastle, V.B. The sense of flutter-vibration: Comparison of the human capacity with response patterns of mechanoreceptive afferents from the monkey hand. J. Neurophysiol. 1968, 31, 301–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, R.S.; Landström, U.; Lundström, R. Responses of mechanoreceptive afferent units in the glabrous skin of the human hand to sinusoidal skin displacements. Brain Res. 1982, 244, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolanowski, S.J.; Gescheider, G.A.; Verrillo, R.T.; Checkosky, C.M. Four channels mediate the mechanical aspects of touch. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1988, 84, 1680–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roll, J.P.; Vedel, J.P. Kinaesthetic role of muscle afferents in man, studied by tendon vibration and microneurography. Exp. Brain Res. 1982, 47, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavounoudias, A.; Roll, R.; Roll, J.P. The plantar sole is a ‘dynamometric map’ for human balance control. Neuroreport 1998, 9, 3247–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creath, R.; Kiemel, T.; Horak, F.; Peterka, R.; Jeka, J. A unified view of quiet and perturbed stance: Simultaneous co-existing excitable modes. Neurosci. Lett. 2005, 377, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavounoudias, A.; Roll, R.; Roll, J.P. Foot sole and ankle muscle inputs contribute jointly to human erect posture regulation. J. Physiol. 2001, 532, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D.A.; Prince, F.; Sterior, P. Medial-lateral and anterior-posterior motor responses associated with center of pressure changes in quiet standing. Neurosci. Res. Commun. 1993, 12, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, C.; Mergner, T.; Bolha, B.; Hlavacka, F. Human balance control during cutaneous stimulation of the plantar soles. Neurosci. Lett. 2001, 302, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, C.; Mergner, T.; Peterka, R.J. Multisensory control of human upright stance. Exp. Brain Res. 2006, 171, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterka, R.J. Sensorimotor integration in human postural control. J. Neurophysiol. 2002, 88, 1097–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterka, R.J. Sensory integration for human balance control. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 159, pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Maheu, M.; Sharp, A.; Landry, S.P.; Champoux, F. Sensory reweighting after loss of auditory cues in healthy adults. Gait Posture 2017, 53, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assländer, L.; Peterka, R.J. Sensory reweighting dynamics following removal and addition of visual and proprioceptive cues. J. Neurophysiol. 2016, 116, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickstein, R.; Abulaffio, N. Postural sway of the affected and nonaffected pelvis and leg in stance of hemiparetic patients. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2000, 81, 364–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, M.G.; Frank, J.S.; Silcher, C.P.; Patla, A.E. The influence of postural threat on the control of upright stance. Exp. Brain Res. 2001, 138, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wark, B.; Lundstrom, B.N.; Fairhall, A. Sensory adaptation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2007, 17, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israr, A.; Poupyrev, I. Tactile brush: Drawing on skin with a tactile grid display. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York City, NY, USA, 7–12 May 2011; pp. 2019–2028. [Google Scholar]

- Palmisano, C.; Brandt, G.; Vissani, M.; Pozzi, N.G.; Canessa, A.; Brumberg, J.; Marotta, G.; Volkmann, J.; Mazzoni, A.; Pezzoli, G.; et al. Gait Initiation in Parkinson’s Disease: Impact of Dopamine Depletion and Initial Stance Condition. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, T.; Ito, T.; Yamashita, N. Effects of changing the initial horizontal location of the center of mass on the anticipatory postural adjustments and task performance associated with step initiation. Gait Posture 2007, 26, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caderby, T.; Yiou, E.; Peyrot, N.; De Vivies, X.; Bonazzi, B.; Dalleau, G. Effects of changing body weight distribution on mediolateral stability control during gait initiation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burleigh-Jacobs, A.; Horak, F.B.; Nutt, J.G.; Obeso, J.A. Step initiation in Parkinson’s disease: Influence of levodopa and external sensory triggers. Mov. Disord. 1997, 12, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraoka, K.; Kunimura, H.; Oda, H.; Kawasaki, T.; Sawaguchi, Y. Rhythmic movement and rhythmic auditory cues enhance anticipatory postural adjustment of gait initiation. Somatosens. Mot. Res. 2020, 37, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kawasaki, T.; Sawaguchi, Y.; Hiraoka, K. Effect of Moving Tactile Stimuli to Sole on Body Sway During Quiet Stance. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121282

Kawasaki T, Sawaguchi Y, Hiraoka K. Effect of Moving Tactile Stimuli to Sole on Body Sway During Quiet Stance. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121282

Chicago/Turabian StyleKawasaki, Taku, Yasushi Sawaguchi, and Koichi Hiraoka. 2025. "Effect of Moving Tactile Stimuli to Sole on Body Sway During Quiet Stance" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121282

APA StyleKawasaki, T., Sawaguchi, Y., & Hiraoka, K. (2025). Effect of Moving Tactile Stimuli to Sole on Body Sway During Quiet Stance. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121282