Enhanced Vigilance Stability during Daytime in Insomnia Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Resting-State EEG Measurement

2.4. Polysomnography

2.5. Psychometric Measures

2.6. EEG Vigilance Classification Using VIGALL

- Stage 0 representing an activated wake state as seen in mental effort. This stage is recognized by a low amplitude EEG with non-alpha-activity, typically without the presence of slow horizontal eye movements.

- Stage A represents relaxed wakefulness: The EEG is dominated by prominent alpha activity. Stage A can be subdivided into A1, A2 and A3, according to the degrees of frontalization of alpha activity from occipital to anterior brain regions. A predominant occipital alpha-activity characterizes stage A1, while alpha-activity shifts to frontal and temporal regions in A2/3 stages accompanied by a decrease in amplitude.

- Stage B corresponds to drowsiness. This stage can be divided into sub-stages B1 (characterized by low amplitude EEG without alpha-activity, with the presence of slow horizontal eye movements) and B2/3 (dominated by theta and/or delta activity).

- Stage C reflects sleep onset. Since this stage is characterized by sleep spindles and K-complexes, its classification is bound to the manually set markers of these EEG phenomena in EEG epochs of 1 s. Spindles and K-complexes were identified according to the criteria of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine [31] by an experienced rater certified in sleep medicine.

- (a)

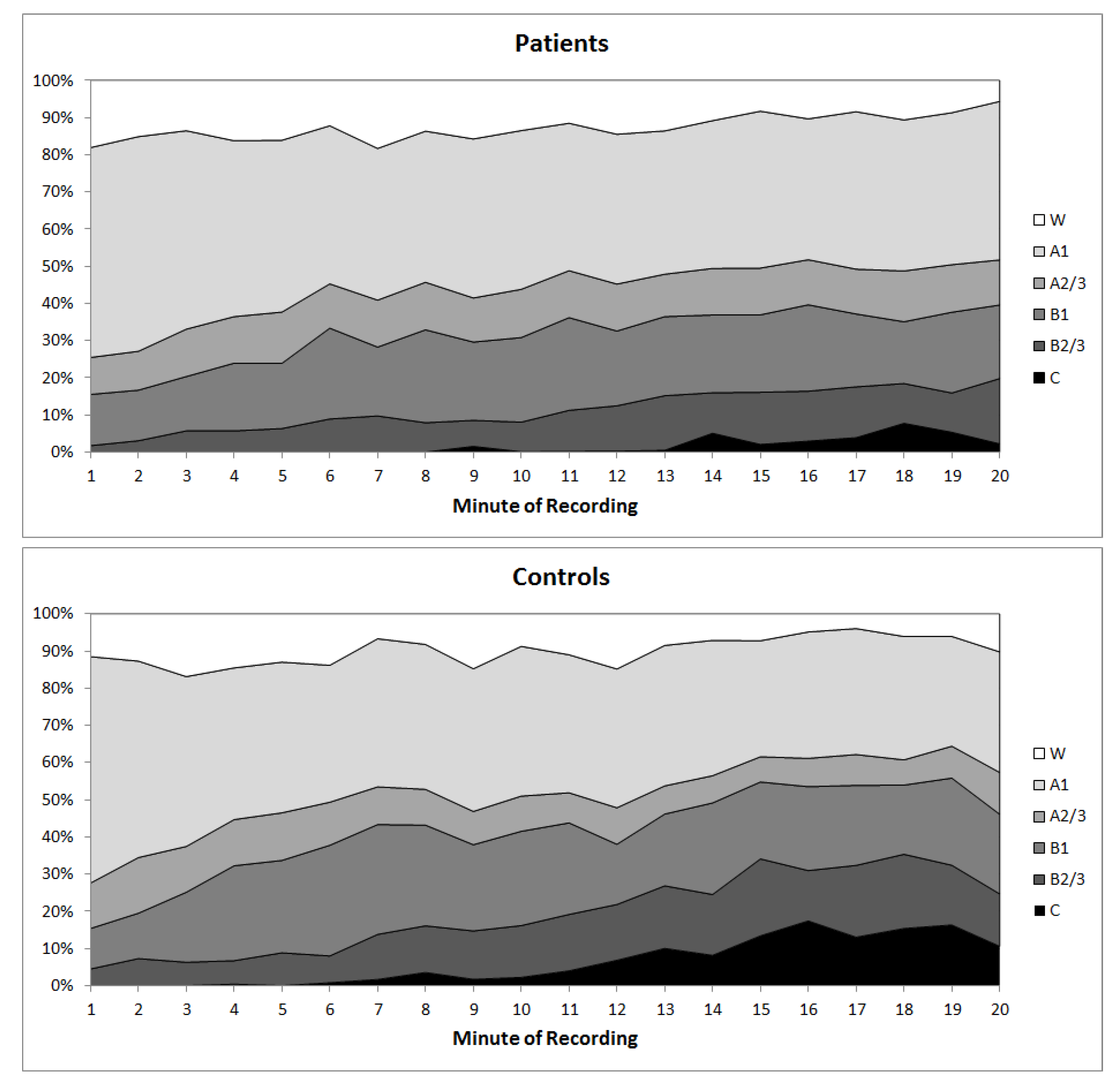

- For each recording minute as well as the total recording period, the absolute amount of vigilance stages (0, A1, A2/3, B1, B2/3 and C) was counted, and the percentage amount was calculated (amount ∗ 100/total number of non-artefact segments).

- (b)

- Furthermore, each EEG vigilance stage is assigned a numerical score ranging from 1–7 (C = 1, B2/3 = 2, B1 = 3, A3 = 4, A2 = 5, A1 = 6, 0 = 7). Again for each recording minute as well as the total recording, a mean vigilance value (MVV) was calculated by averaging the scores of all non-artefact segments.

- (c)

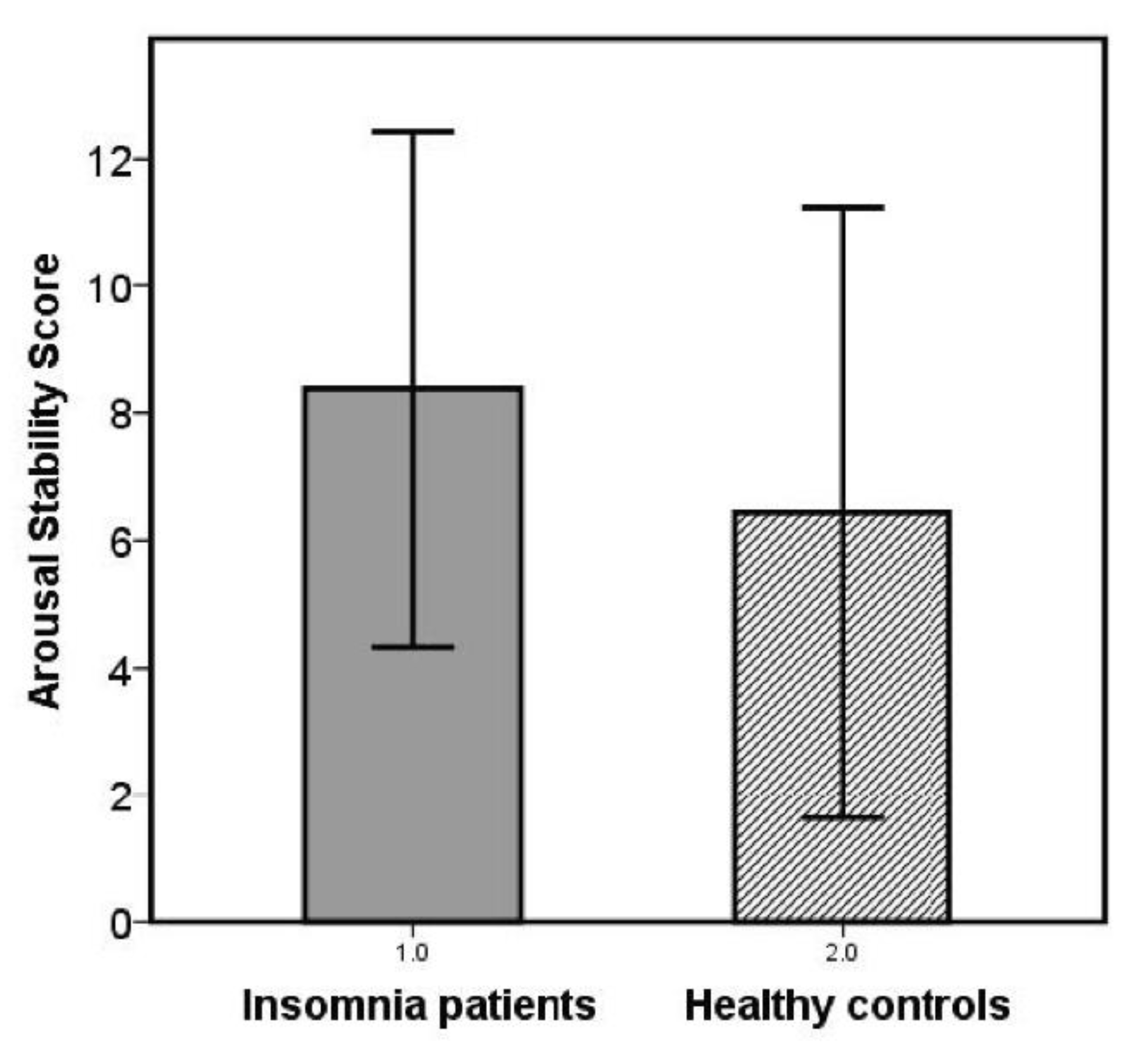

- In addition, an arousal stability score (ASS) was determined for each subject’s EEG vigilance time course to quantify the speed and extent of the respective decline in brain arousal. For this, successive blocks with a duration of 1 min were analyzed concerning fulfilment of one of the following criteria: (I) at least 2/3 of all segments classified as 0/A or 0/A1 stages; (II) at least 1/3 of all segments classified as B stages (B1 + B2/3); (III) at least 1/3 of all segments classified as B2/3 stages; (IV) occurrence of at least 1 C stage. The 20-min EEG recording was separated into four consecutive 5-min epochs (quartiles). If only criterion I was fulfilled during the whole recording, a high ASS-score is given (14 (only 0/A1 stages) or 13 (only 0/A-stages)). Depending on which of the criteria II to IV were achieved in which quarter of the measurement, increasingly lower ASS scores were awarded (e.g., C stages reached within the last quarter: ASS = 4, C-stages reached within the first quarter: ASS = 1). Thus, higher ASS scores correspond to higher arousal stability.

- (d)

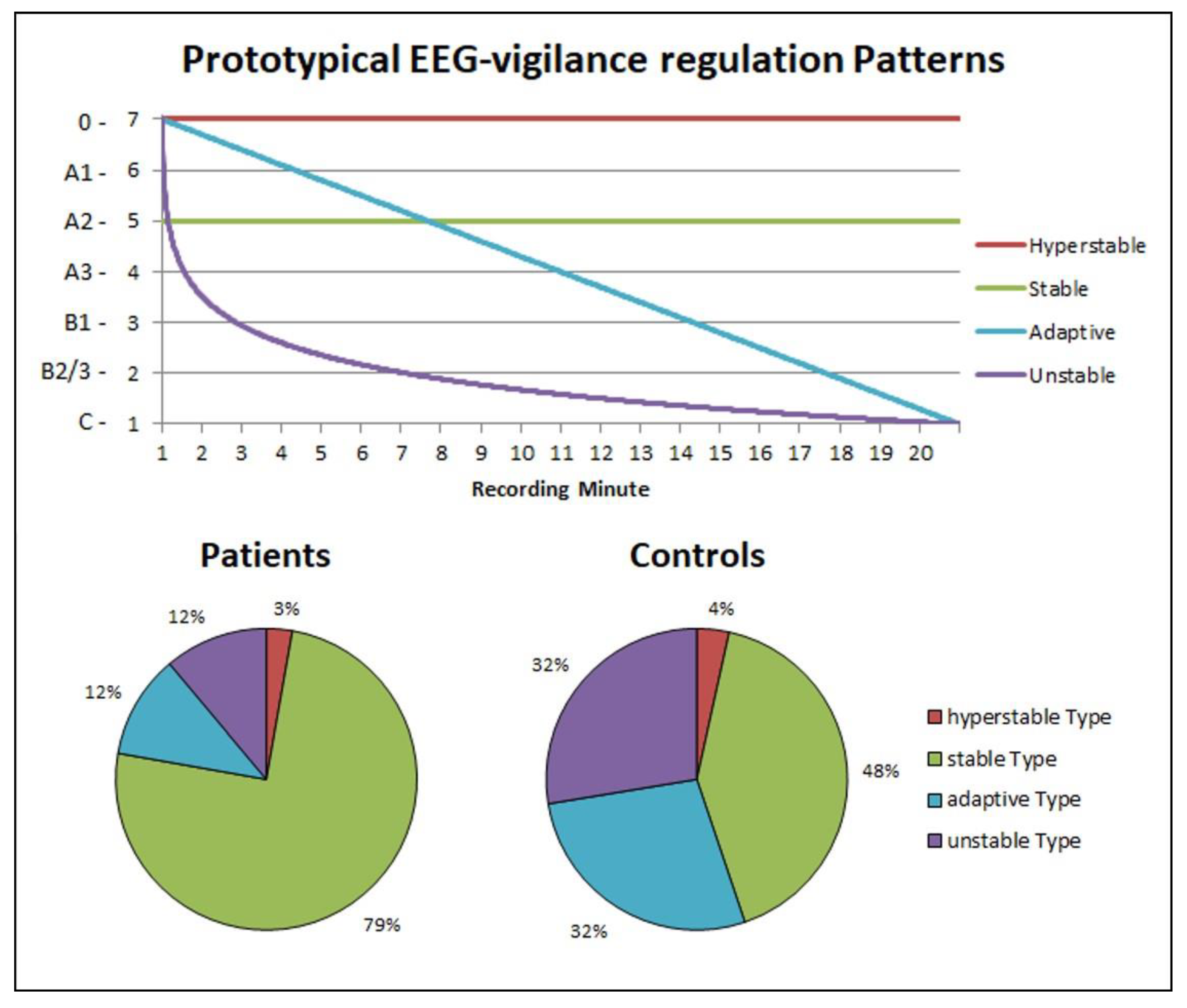

- Individual time courses were compared with prototypical time courses corresponding to the three prototypical types of brain arousal regulation according the model of Hegerl et al. [43]: adaptive vigilance regulation (graduated decrease in vigilance over time), unstable vigilance regulation (accelerated decrease in vigilance) and (hyper) stable vigilance regulation (absence of vigilance decrease). Each participant was assigned to the prototype course with the smallest sum of deviation squares. Post hoc, an additional model distinguishing four prototypes of brain arousal regulation was calculated. In this model, in addition to the adaptive and the unstable regulatory type, a stable (no vigilance decrease over time) and a hyperstable regulatory (retention in the highest arousal states) type were distinguished.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Group Differences in Polysomnographic and Psychometric Measures

3.2. Daytime Vigilance Stability

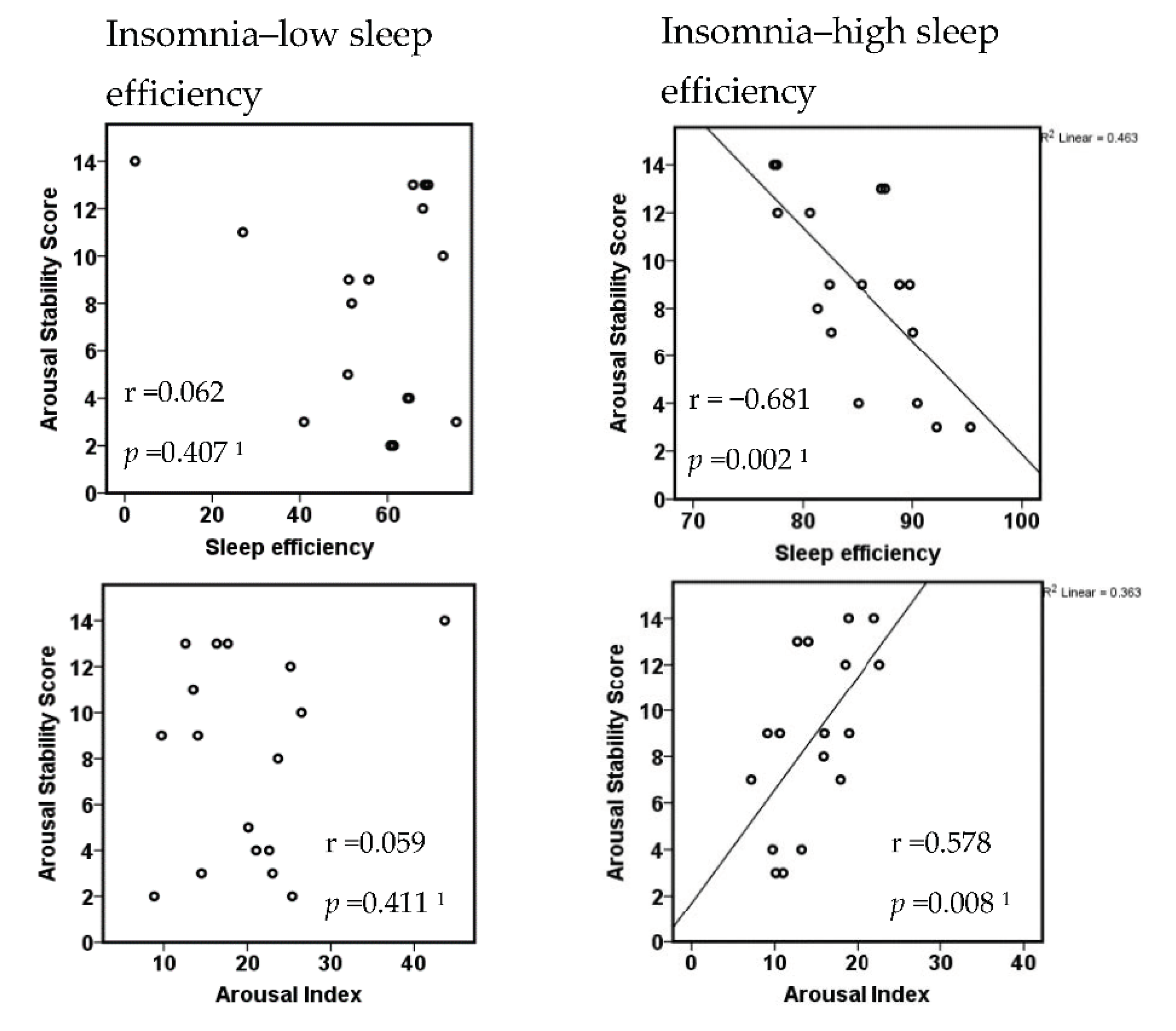

3.3. Insomnia Subtypes with Respect to the Extent of Objective Sleep Disturbance

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ohayon, M.M. Epidemiology of insomnia: What we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med. Rev. 2002, 6, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leger, D.; Guilleminault, C.; Bader, G.; Levy, E.; Paillard, M. Medical and socio-professional impact of insomnia. Sleep 2002, 25, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baglioni, C.; Battagliese, G.; Feige, B.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Nissen, C.; Voderholzer, U.; Lombardo, C.; Riemann, D. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 135, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnet, M.H.; Arand, D.L. Hyperarousal and insomnia: State of the science. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemann, D.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Feige, B.; Voderholzer, U.; Berger, M.; Perlis, M.; Nissen, C. The hyperarousal model of insomnia: A review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalmbach, D.A.; Anderson, J.R.; Drake, C.L. The impact of stress on sleep: Pathogenic sleep reactivity as a vulnerability to insomnia and circadian disorders. J. Sleep Res. 2018, 27, e12710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, A.G. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behav. Res. Ther. 2002, 40, 869–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vgontzas, A.N.; Bixler, E.O.; Lin, H.M.; Prolo, P.; Mastorakos, G.; Vela-Bueno, A.; Kales, A.; Chrousos, G.P. Chronic insomnia is associated with nyctohemeral activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: Clinical implications. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 3787–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelman, J.W.; Buxton, O.M.; Jensen, J.E.; Benson, K.L.; O’Connor, S.P.; Wang, W.; Renshaw, P.F. Reduced brain GABA in primary insomnia: Preliminary data from 4T proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS). Sleep 2008, 31, 1499–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, D.B.; Buysse, D.J. Hyperarousal and Beyond: New Insights to the Pathophysiology of Insomnia Disorder through Functional Neuroimaging Studies. Brain Sci. 2017, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlis, M.L.; Merica, H.; Smith, M.T.; Giles, D.E. Beta EEG activity and insomnia. Sleep Med. Rev. 2001, 5, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedner, B.A.; Goldstein, M.R.; Plante, D.T.; Rumble, M.E.; Ferrarelli, F.; Tononi, G.; Benca, R.M. Regional Patterns of Elevated Alpha and High-Frequency Electroencephalographic Activity during Nonrapid Eye Movement Sleep in Chronic Insomnia: A Pilot Study. Sleep 2016, 39, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feige, B.; Baglioni, C.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Hirscher, V.; Nissen, C.; Riemann, D. The microstructure of sleep in primary insomnia: An overview and extension. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2013, 89, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merica, H.; Gaillard, J.M. The EEG of the sleep onset period in insomnia: A discriminant analysis. Physiol. Behav. 1992, 52, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglioni, C.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Regen, W.; Feige, B.; Nissen, C.; Lombardo, C.; Violani, C.; Hennig, J.; Riemann, D. Insomnia disorder is associated with increased amygdala reactivity to insomnia-related stimuli. Sleep 2014, 37, 1907–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, V.; Roth, T.; Drake, C.L. The nature of stable insomnia phenotypes. Sleep 2015, 38, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanski, E.; Zorick, F.; Roehrs, T.; Young, D.; Roth, T. Daytime alertness in patients with chronic insomnia compared with asymptomatic control subjects. Sleep 1988, 11, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, M.H.; Arand, D.L. 24-Hour metabolic rate in insomniacs and matched normal sleepers. Sleep 1995, 18, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roehrs, T.A.; Randall, S.; Harris, E.; Maan, R.; Roth, T. MSLT in primary insomnia: Stability and relation to nocturnal sleep. Sleep 2011, 34, 1647–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, M.A.; Ramautar, J.R.; Wei, Y.; Gomez-Herrero, G.; Stoffers, D.; Wassing, R.; Benjamins, J.S.; Tagliazucchi, E.; van der Werf, Y.D.; Cajochen, C.; et al. Wake High-Density Electroencephalographic Spatiospectral Signatures of Insomnia. Sleep 2016, 39, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi-Cabrera, M.; Figueredo-Rodríguez, P.; del Río-Portilla, Y.; Sánchez-Romero, J.; Galán, L.; Bosch-Bayard, J. Enhanced frontoparietal synchronized activation during the wake-sleep transition in patients with primary insomnia. Sleep 2012, 35, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi-Cabrera, M.; Rojas-Ramos, O.A.; del Río-Portilla, Y. Waking EEG signs of non-restoring sleep in primary insomnia patients. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2016, 127, 1813–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.M.; Pietrone, R.; Cashmere, J.D.; Begley, A.; Miewald, J.M.; Germain, A.; Buysse, D.J. EEG power during waking and NREM sleep in primary insomnia. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2013, 9, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, C.; Hensch, T.; Wittekind, D.A.; Bottger, D.; Hegerl, U. Assessment of Wakefulness and Brain Arousal Regulation in Psychiatric Research. Neuropsychobiology 2015, 72, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegerl, U.; Wilk, K.; Olbrich, S.; Schoenknecht, P.; Sander, C. Hyperstable regulation of vigilance in patients with major depressive disorder. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 13, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, S.E.; Cuthbert, B.N. Research Domain Criteria: Cognitive systems, neural circuits, and dimensions of behavior. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 14, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jawinski, P.; Kirsten, H.; Sander, C.; Spada, J.; Ulke, C.; Huang, J.; Burkhardt, R.; Scholz, M.; Hensch, T.; Hegerl, U. Human brain arousal in the resting state: A genome-wide association study. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 1599–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, J.M.; Jones, S.E.; Dashti, H.S.; Wood, A.R.; Aragam, K.G.; van Hees, V.T.; Strand, L.B.; Winsvold, B.S.; Wang, H.; Bowden, J.; et al. Biological and clinical insights from genetics of insomnia symptoms. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vgontzas, A.N.; Fernandez-Mendoza, J.; Liao, D.; Bixler, E.O. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration: The most biologically severe phenotype of the disorder. Sleep Med. Rev. 2013, 17, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [CrossRef]

- Iber, C.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; Chesson, A.; Quan, S.F. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology, and Technical Specifications, 1st ed.; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Westchester, IN, USA, 2007; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Bastien, C.H.; Vallieres, A.; Morin, C.M. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coren, S.; Mah, K.B. Prediction of physiological arousability: A validation of the Arousal Predisposition Scale. Behav. Res. Ther. 1993, 31, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicassio, P.M.; Mendlowitz, D.R.; Fussell, J.J.; Petras, L. The phenomenology of the pre-sleep state: The development of the pre-sleep arousal scale. Behav. Res. Ther. 1985, 23, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, M.W. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991, 14, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoddes, E.; Zarcone, V.; Smythe, H.; Phillips, R.; Dement, W.C. Quantification of sleepiness: A new approach. Psychophysiology 1973, 10, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waine, J.; Broomfield, N.M.; Banham, S.; Espie, C.A. Metacognitive beliefs in primary insomnia: Developing and validating the Metacognitions Questionnaire—Insomnia (MCQ-I). J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2009, 40, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlotz, W.; Yim, I.S.; Zoccola, P.M.; Jansen, L.; Schulz, P. The Perceived Stress Reactivity Scale: Measurement invariance, stability, and validity in three countries. Psychol Assess. 2011, 23, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griefahn, B.; Künemund, C.; Bröde, P.; Mehnert, P. Zur Validität der deutschen Übersetzung des Morningness-Eveningness-Questionnaires von Horne und Östberg. Somnologie 2001, 5, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sander, C.; Jawinski, P.; Ulke, C.; Spada, J.; Hegerl, U.; Hensch, T. Test-retest reliability of brain arousal regulation as assessed with VIGALL 2.0. Neuropsychiatr. Electrophysiol. 2015, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegerl, U.; Hensch, T. The vigilance regulation model of affective disorders and ADHD. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 44, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshkowitz, M.; Sharafkhaneh, A. Evaluating sleepiness. In Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine, 6th ed.; Kryger, M., Roth, T., Dement, W.C., Eds.; Elsevier: Philidelphia, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 1651–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, J. Primary insomnia: A disorder of sleep, or primarily one of wakefulness? Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang-Vu, T.T.; Salimi, A.; Boucetta, S.; Wenzel, K.; O’Byrne, J.; Brandewinder, M.; Berthomier, C.; Gouin, J.P. Sleep spindles predict stress-related increases in sleep disturbances. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Normand, M.P.; St-Hilaire, P.; Bastien, C.H. Sleep Spindles Characteristics in Insomnia Sufferers and Their Relationship with Sleep Misperception. Neural. Plast. 2016, 2016, 6413473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forget, D.; Morin, C.M.; Bastien, C.H. The role of the spontaneous and evoked k-complex in good-sleeper controls and in individuals with insomnia. Sleep 2011, 34, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Colombo, M.A.; Ramautar, J.R.; Blanken, T.F.; van der Werf, Y.D.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Feige, B.; Riemann, D.; Van Someren, E.J.W. Sleep Stage Transition Dynamics Reveal Specific Stage 2 Vulnerability in Insomnia. Sleep 2017, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.A.E.; Wassing, R.; Wei, Y.; Ramautar, J.R.; Lakbila-Kamal, O.; Jennum, P.J.; Van Someren, E.J.W. Data-Driven Analysis of EEG Reveals Concomitant Superficial Sleep During Deep Sleep in Insomnia Disorder. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, C.H.; St-Jean, G.; Turcotte, I.; Morin, C.M.; Lavallee, M.; Carrier, J. Sleep spindles in chronic psychophysiological insomnia. J. Psychosom. Res. 2009, 66, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, C.H.; St-Jean, G.; Turcotte, I.; Morin, C.M.; Lavallée, M.; Carrier, J.; Forget, D. Spontaneous K-complexes in chronic psychophysiological insomnia. J. Psychosom. Res. 2009, 67, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, D.; Klein, T.; Rodenbeck, A.; Feige, B.; Horny, A.; Hummel, R.; Weske, G.; Al-Shajlawi, A.; Voderholzer, U. Nocturnal cortisol and melatonin secretion in primary insomnia. Psychiatry Res. 2002, 113, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, C.L.; Pillai, V.; Roth, T. Stress and sleep reactivity: A prospective investigation of the stress-diathesis model of insomnia. Sleep 2014, 37, 1295–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagini, L.; Mauri, M.; Dell'Osso, L.; Riemann, D.; Drake, C.L. Trait- and pre-sleep-state-dependent arousal in insomnia disorders: What role may sleep reactivity and sleep-related metacognitions play? A pilot study. Sleep Med. 2016, 25, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmbach, D.A.; Cuamatzi-Castelan, A.S.; Tonnu, C.V.; Tran, K.M.; Anderson, J.R.; Roth, T.; Drake, C.L. Hyperarousal and sleep reactivity in insomnia: Current insights. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2018, 10, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanken, T.F.; Benjamins, J.S.; Borsboom, D.; Vermunt, J.K.; Paquola, C.; Ramautar, J.; Dekker, K.; Stoffers, D.; Wassing, R.; Wei, Y.; et al. Insomnia disorder subtypes derived from life history and traits of affect and personality. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Insomnia (n = 34) | Healthy Controls (n = 25) | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 44.1 ± 12.5 | 39.2 ± 13.0 | 1.5 | 0.153 |

| Sex (w/m) | 27/7 | 19/6 | 0.1 1 | 0.755 |

| Psychometric data | ||||

| Disturbed sleep quality (PSQI) | 11.9 ± 3.1 2 | 4.3 ± 2.3 | 9.9 | 0.000 * |

| Insomnia severity (ISI) | 17.5 ± 4.3 3 | 3.0 ± 3.1 4 | 14.2 | 0.000 * |

| Sleep-related beliefs (MCQ-I) | 123.3 ± 30.1 | 98.4 ± 21.4 | 3.5 | 0.001 * |

| Stress reactivity (PSRS-23) | 25.6 ± 9.1 | 16.7 ± 5.5 | 4.7 | 0.000 * |

| Trait arousal (APS) | 33.9 ± 6.2 | 28.4 ± 4.3 | 3.8 | 0.000 * |

| Sleepiness (ESS) | 7.0 ± 5.2 | 7.2 ± 4.3 | −0.2 | 0.876 |

| Depressiveness (BDI 1–10) | 3.2 ± 3.3 2 | 1.2 ± 1.8 | 2.7 | 0.010 * |

| Morningness–Eveningness (D-MEQ) | 56.0 ± 8.2 5 | 54.6 ± 9.1 | 0.6 | 0.544 |

| State arousal (PSAS) | ||||

| Arousal | 26.6 ± 8.6 | 18.3 ± 3.1 | 4.6 | 0.000 * |

| Somatic arousal | 12.1 ± 4.6 | 8.8 ± 1.2 | 4.0 | 0.000 * |

| Cognitive arousal | 14.5 ± 5.5 | 9.5 ± 2.5 | 4.6 | 0.000 * |

| State Sleepiness (KSS) | ||||

| Pre EEG | 5.3 ± 1.7 | 3.5 ± 1.9 | 3.8 | 0.000 * |

| Post EEG | 5.3 ± 2.0 | 4.7 ± 2.1 | 1.1 | 0.274 |

| pre–post diff | 0.0 ± 2.4 | 1.2 ± 2.8 | −1.8 | 0.085 (*) |

| Sleep parameters | ||||

| Sleep latency (min) | 31.9 ± 34.2 | 25.6 ± 17.8 | 0.8 | 0.405 |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 70.7 ± 20.1 | 83.6 ± 12.9 | −3.0 | 0.004 * |

| WASO (min) | 91.7 ± 63.9 | 42.9 ± 42.8 | 3.5 | 0.001 * |

| Total sleep time (min) | 323 ± 92 | 382 ± 58 | −3.0 | 0.004 * |

| % Stage 1 | 14.2 ± 5.8 | 12.2 ± 5.2 | 1.4 | 0.171 |

| % Stage 2 | 38.4 ± 11.3 | 43.9 ± 8.7 | −2.0 | 0.051 (*) |

| % Stage 3 | 13.4 ± 7.4 | 20.8 ± 9.7 | −3.3 | 0.001 * |

| % REM | 10.5 ± 5.1 | 12.7 ± 5.4 | −1.6 | 0.125 |

| Arousal index | 17.3 ± 7.1 | 14.0 ± 8.0 | 1.7 | 0.104 |

| Number of wake periods | 29.8 ± 13.4 | 23.8 ± 12.0 | 1.8 | 0.081 (*) |

| Insomnia (n = 34) | Healthy Subjects (n = 25) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | |

| Subjective sleep | ||||

| Insomnia severity (ISI) | −0.116 1 | 0.529 | 0.009 2 | 0.968 |

| Objective sleep | ||||

| Sleep efficiency (SE) | −0.058 | 0.372 3 | −0.064 | 0.761 |

| Arousal index (AI) | 0.199 | 0.129 3 | −0.106 | 0.614 |

| Psychometric parameters | ||||

| Stress reactivity (PSRS-23) | −0.035 | 0.846 | −0.093 | 0.660 |

| Trait arousal (APS) | 0.075 | 0.671 | 0.058 | 0.784 |

| State arousal (PSAS) | ||||

| Arousal | 0.135 | 0.447 | −0.139 | 0.507 |

| Somatic arousal | 0.145 | 0.414 | −0.121 | 0.565 |

| Cognitive arousal | 0.148 | 0.403 | 0.124 | −0.554 |

| Insomnia-related beliefs (MCQ-I) | −0.205 | 0.244 | 0.045 | 0.836 |

| Depressiveness (BDI 1–10) | −0.060 1 | 0.745 | 0.236 | 0.257 |

| Low Sleep Efficiency (n = 17) | High Sleep Efficiency (n = 17) | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arousal Stability Score | 7.9 ± 4.4 | 8.8 ± 3.8 | 0.6 1 | 0.534 |

| Subjective insomnia severity | ||||

| Disturbed sleep quality (PSQI) | 11.7 ± 3.2 | 12.1 ± 3.0 | 0.3 | 0.755 |

| Insomnia severity (ISI) | 17.4 ± 3.9 | 17.7 ± 4.8 | 0.2 | 0.805 |

| Psychometrics | ||||

| Insomnia-related beliefs (MCQ-I) | 114.8 ± 24.4 | 131.8 ± 33.4 | 2.9 | 0.100 |

| Depressiveness (BDI 1–10) | 2.5 ± 2.3 | 4.0 ± 4.0 | 1.3 | 0.191 |

| Stress reactivity (PSRS-23) | 27.1 ± 8.6 | 24.1 ± 9.5 | −0.9 | 0.352 |

| Sleepiness (ESS) | 6.4 ± 5.5 | 7.9 ± 5.0 | 0.7 | 0.520 |

| Trait arousal (APS) | 34.2 ± 5.1 | 33.6 ± 7.2 | −0.3 | 0.786 |

| State sleepiness (KSS) | ||||

| pre EEG | 5.8 ± 1.5 | 4.8 ± 1.9 | −1.7 | 0.095 (*) |

| post EEG | 5.4 ± 1.7 | 5.1 ± 2.3 | −0.4 | 0.671 |

| pre post diff | −0.4 ± 1.8 | 0.4 ± 3.0 | 0.8 | 0.410 |

| State Arousal (PSAS) | ||||

| Arousal | 26.2 ± 7.9 | 26.9 ± 9.4 | 0.2 | 0.830 |

| Somatic arousal | 11.7 ± 4.0 | 12.4 ± 5.1 | 0.4 | 0.659 |

| Cognitive arousal | 14.5 ± 5.2 | 14.5 ± 5.9 | 0.0 | 1.00 |

| History of previous depressive episode | 6/17 | 3/17 | 1.4 2 | 0.244 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Losert, A.; Sander, C.; Schredl, M.; Heilmann-Etzbach, I.; Deuschle, M.; Hegerl, U.; Schilling, C. Enhanced Vigilance Stability during Daytime in Insomnia Disorder. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 830. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10110830

Losert A, Sander C, Schredl M, Heilmann-Etzbach I, Deuschle M, Hegerl U, Schilling C. Enhanced Vigilance Stability during Daytime in Insomnia Disorder. Brain Sciences. 2020; 10(11):830. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10110830

Chicago/Turabian StyleLosert, Ariane, Christian Sander, Michael Schredl, Ivonne Heilmann-Etzbach, Michael Deuschle, Ulrich Hegerl, and Claudia Schilling. 2020. "Enhanced Vigilance Stability during Daytime in Insomnia Disorder" Brain Sciences 10, no. 11: 830. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10110830

APA StyleLosert, A., Sander, C., Schredl, M., Heilmann-Etzbach, I., Deuschle, M., Hegerl, U., & Schilling, C. (2020). Enhanced Vigilance Stability during Daytime in Insomnia Disorder. Brain Sciences, 10(11), 830. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10110830