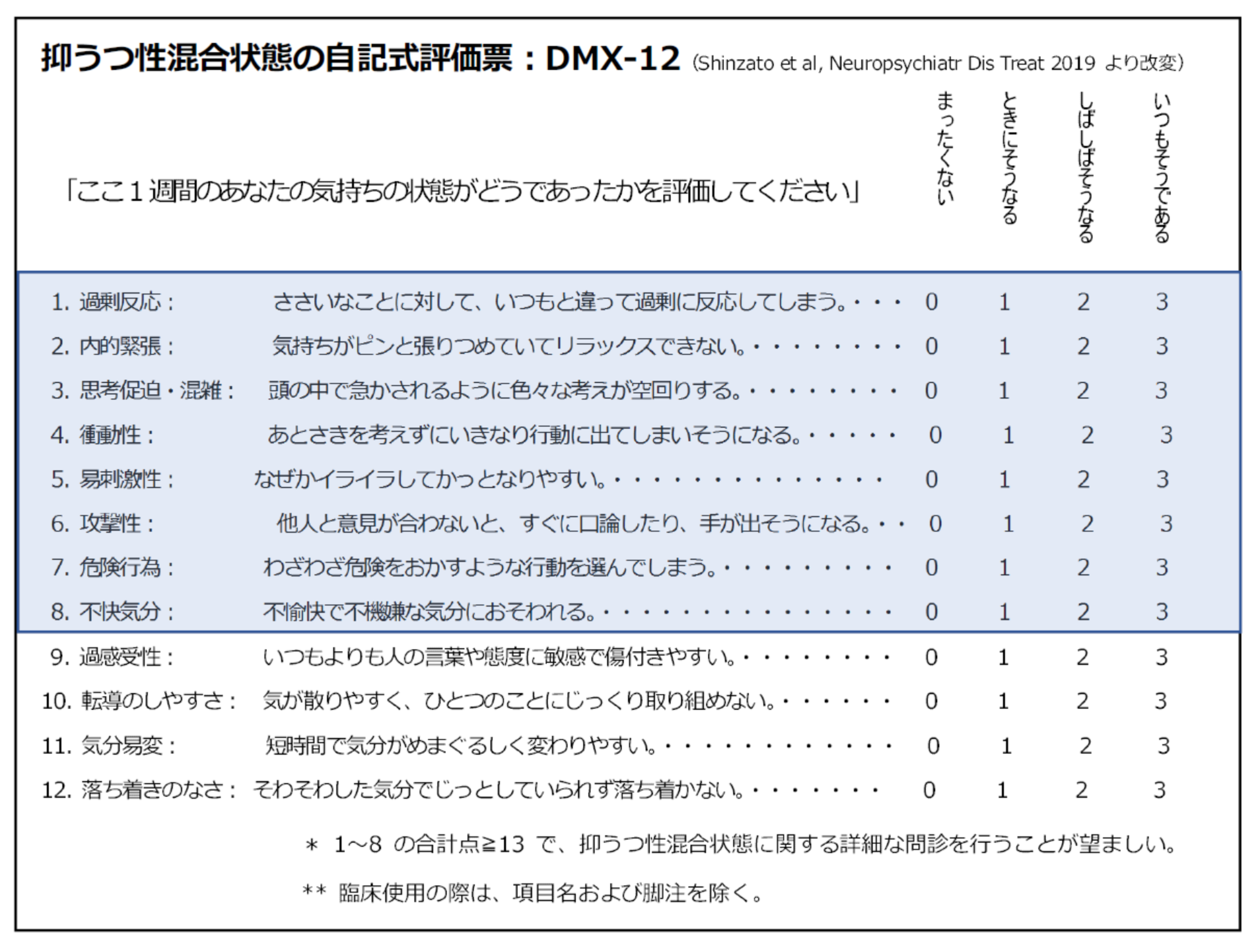

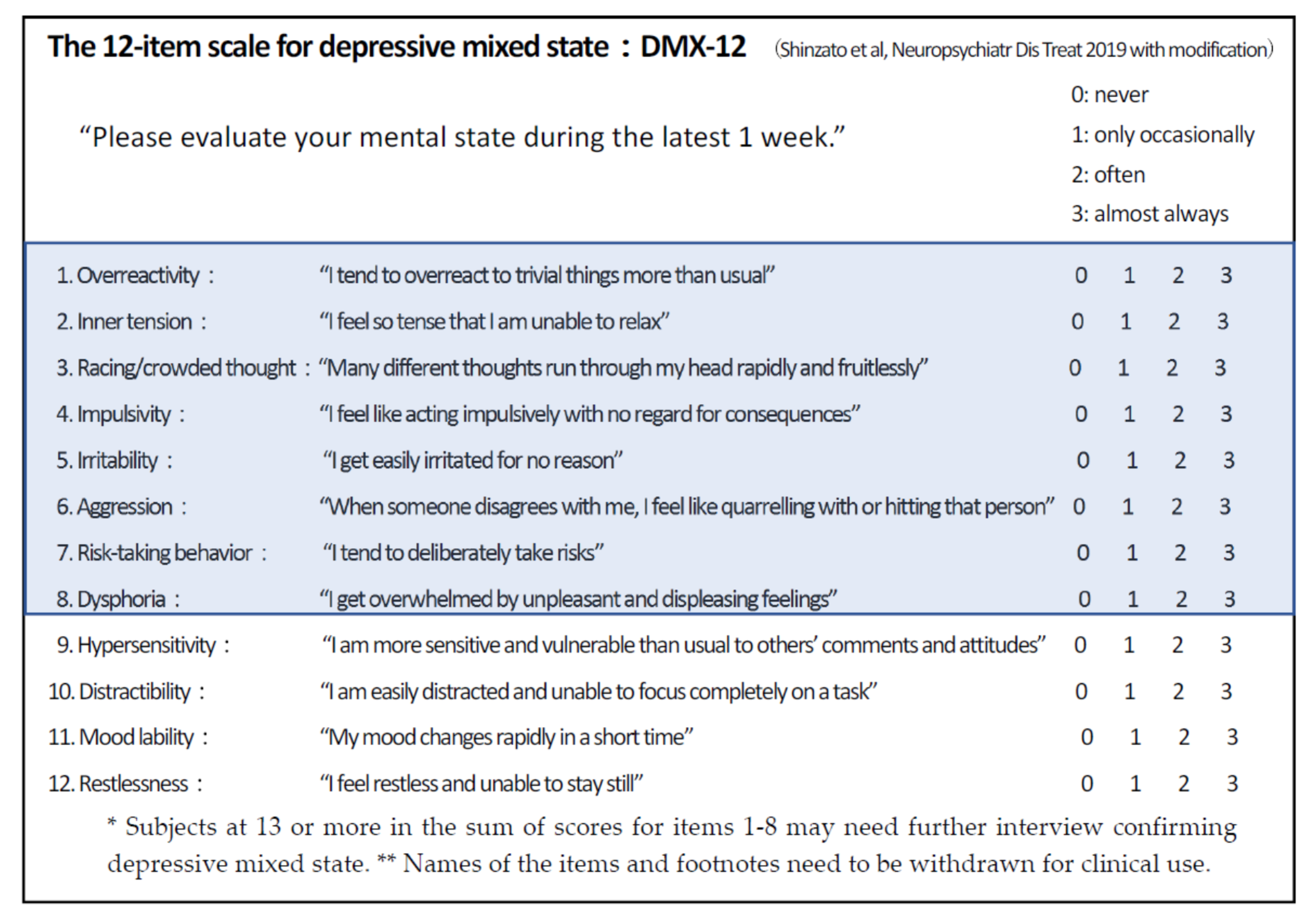

The 12-Item Self-Rating Questionnaire for Depressive Mixed State (DMX-12) for Screening of Mixed Depression and Mixed Features

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Subjects and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Assessments and Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Fornaro, M.; Martino, M.; Pasquale, D.C.; Moussaoui, D. The argument of antidepressant drugs in the treatment of bipolar depression: Mixed evidence or mixed states? Expert Opin. Pharm. 2012, 13, 2037–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.S.; Lampe, L.; Coulston, C.M.; Tanious, M.; Bargh, D.M.; Curran, G.; Kuiper, S.; Morgan, H.; Fritz, K. Mixed state discrimination: A DSM problem that won’t go away? J. Affect Disord. 2014, 158, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, T.; Shinzato, H.; Koda, M. Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations in depressive mixed state. Clin. Neuropsychopharmacol. Ther. 2016, 7, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunze, H.; Vieta, E.; Goodwin, G.M.; Bowden, C.; Licht, R.W.; Azorin, J.M.; Yatham, L.; Mosolov, S.; Möller, H.J.; Kasper, S. The world federation of societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: Acute and long-term treatment of mixed states in bipolar disorder. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 19, 2–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Pub: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Pub: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Perugi, G.; Angst, J.; Azorin, J.M.; Bowden, C.L.; Mosolov, S.; Reis, J.; Vieta, E.; Young, A.H. Mixed features in patients with a major depressive episode: The BRIDGE-II-MIX study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2015, 76, e351–e358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshima, M.; Oka, T. DSM-5-defined “mixed features” and Benazzi’s mixed depression: Which is practically useful to discriminate bipolar disorder from unipolar depression in patients with depression? Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 69, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bartoli, F.; Crocamo, C.; Carrà, G. Clinical correlates of DSM-5 mixed features in bipolar disorder: A meta-analysis. J. Affect Disord. 2020, 276, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhi, G.S.; Fritz, K.; Allwang, C.; Burston, N.; Cocks, C.; Devlin, J.; Harper, M.; Hoadley, B.; Kearney, B.; Klug, P.; et al. Are manic symptoms that “dip” into depression the essence of mixed features? J. Affect Disord. 2016, 192, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, A.C. Mixed features: Evolution of the concept, past and current definitions, and future prospects. CNS Spectr. 2017, 22, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogasawara, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Kimura, H.; Aleksic, B.; Ozaki, N. Issues on the diagnosis and etiopathogenesis of mood disorders: Reconsidering DSM-5. J. Neural Transm. 2018, 125, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benazzi, F. Which could be a clinically useful definition of depressive mixed state? Prog. Neuro Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2002, 26, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benazzi, F. Bipolar disorder-focus on bipolar II disorder and mixed depression. Lancet 2007, 369, 935–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benazzi, F. Defining mixed depression. Prog. Neuro Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 32, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benazzi, F. A Tetrachoric factor analysis validation of mixed depression. Prog. Neuro Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 32, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinzato, H.; Koda, M.; Nakamura, A.; Kondo, T. Development of the 12-Item questionnaire for quantitative assessment of depressive mixed state (DMX-12). Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2019, 15, 1983–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sani, G.; Vöhringer, P.A.; Napoletano, F.; Holtzman, N.S.; Dalley, S.; Girardi, P.; Nassir Ghaemi, S.; Koukopoulos, A. Koukopoulos’ diagnostic criteria for mixed depression: A validation study. J. Affect Disord. 2014, 164, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bertschy, G.; Gervasoni, N.; Favre, S.; Liberek, C.; Ragama-Pardos, E.; Aubry, J.-M.; Gex-Fabry, M.; Dayer, A. Phenomenology of mixed states: A principal component analysis study. Bipolar. Disord. 2007, 9, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.; M’Bailara, K.; Mathieu, F.; Poinsot, R.; Falissard, B. Construction and validation of a dimensional scale exploring mood disorders: MAThyS (multidimensional assessment of thymic states). BMC Psychiatry 2008, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Azorin, J.M.; Kaladjian, A.; Adida, M.; Fakra, E.; Belzeaux, R.; Hantouche, E.; Lancrenon, S. Self-assessment and characteristics of mixed depression in the french national EPIDEP study. J. Affect Disord. 2012, 143, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, G.; Vöhringer, P.A.; Barroilhet, S.A.; Koukopoulos, A.E.; Ghaemi, S.N. The koukopoulos mixed depression rating scale (KMDRS): An international mood network (IMN) validation study of a new mixed mood rating scale. J. Affect Disord. 2018, 232, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benazzi, F. A relationship between bipolar II disorder and borderline personality disorder? Prog. Neuro Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 32, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaemi, S.N.; Dalley, S. The bipolar spectrum: Conceptions and misconceptions. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mixed Depression | Mixed Features | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present (n = 43) | Absent (n = 147) | p | Present (n = 8) | Absent (n = 182) | p | |

| Age (years) | 40.1 ± 17.3 | 44.6 ± 17.8 | 0.121 | 43.5 ± 20.7 | 43.5 ± 17.7 | 0.885 |

| Female gender (%) | 67.4% | 60.5% | 0.412 | 62.5% | 62.1% | 1.000 |

| Number of mood episodes | 4.0 ± 3.5 | 2.9 ± 2.9 | 0.022 | 6.3 ± 4.1 | 3.0 ± 2.9 | 0.012 |

| Duration of illness (year) | 7.8 ± 8.6 | 6.5 ± 7.7 | 0.265 | 9.9 ± 7.9 | 6.7 ± 7.9 | 0.188 |

| High education level (%) | 37.2% | 38.8% | 0.828 | 62.5% | 37.4% | 0.264 |

| Bipolarity (%) | 48.8% | 21.1% | 0.001 | 75.0% | 25.3% | 0.006 |

| DMX-12 (total score) | 22.9 ± 5.8 | 17.0 ± 8.0 | 0.001 | 24.4 ± 7.7 | 18.1 ± 7.9 | 0.034 |

| Mixed Depression (MD) | Mixed Features (MF) | |

|---|---|---|

| Vulnerable responsiveness | ||

| Hypersensitivity | 0.591 | 0.410 |

| →Overreactivity | 0.692 | 0.665 |

| Spontaneous instability | ||

| Distractibility | 0.586 | 0.486 |

| Mood lability | 0.581 | 0.622 |

| Restlessness | 0.590 | 0.644 |

| →Inner tension | 0.641 | 0.630 |

| →Racing/crowded thought | 0.634 | 0.645 |

| →Impulsivity | 0.651 | 0.786 |

| Disruptive emotion/behavior | ||

| →Irritability | 0.645 | 0.671 |

| →Aggression | 0.650 | 0.728 |

| →Risk-taking behavior | 0.651 | 0.804 |

| →Dysphoria | 0.713 | 0.644 |

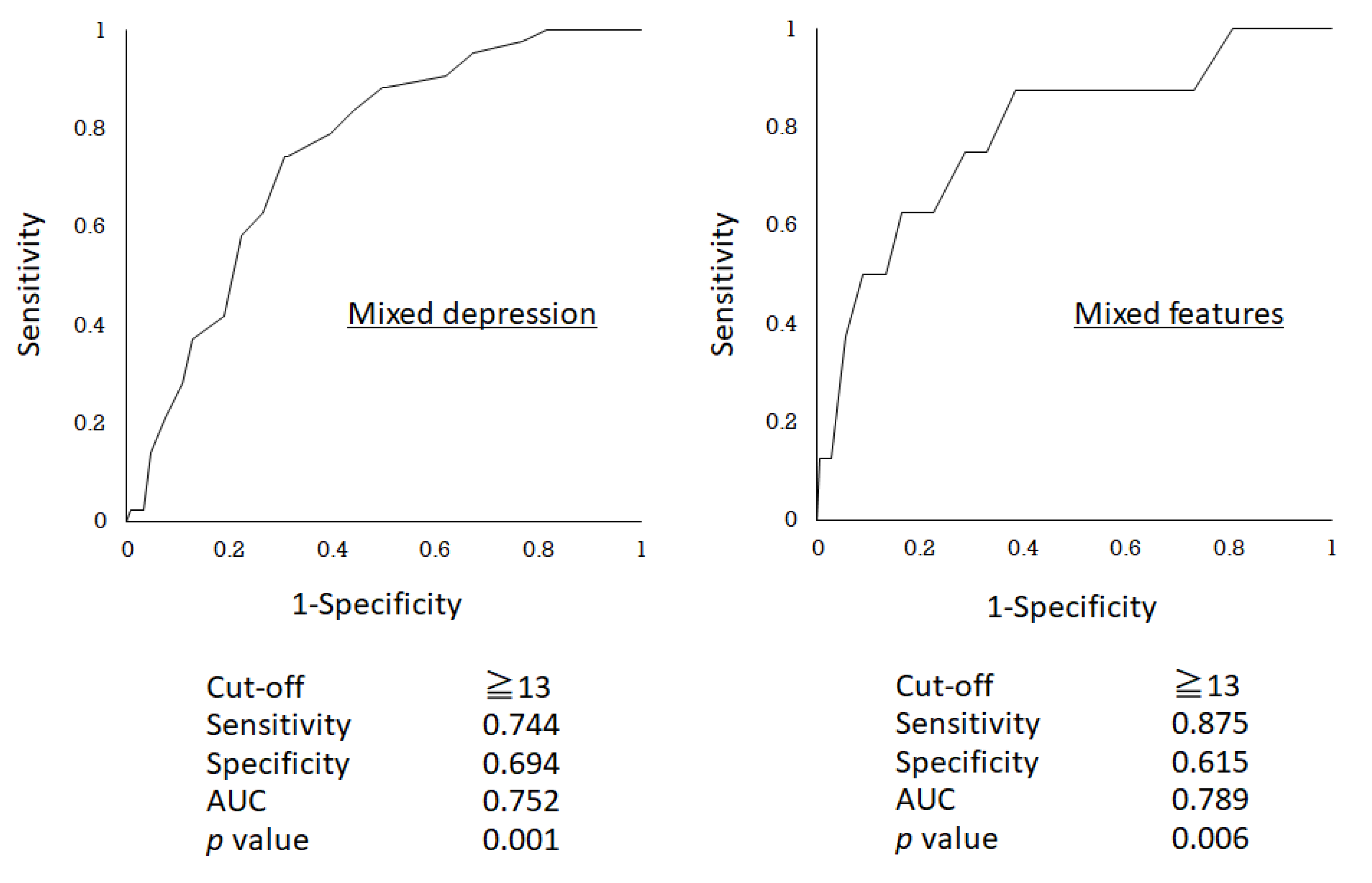

| Cut-Off (Positive Ratio %) | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | AUC of ROC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed depression | ||||||

| Total score of the DMX-12 | ≥19 (47.9%) | 0.767 | 0.605 | 0.363 | .899 | 0.720 |

| 4 symptoms of disruptive emotion/behavior subscale | ≥4 (50.5%) | 0.814 | 0.585 | 0.365 | 0.915 | 0.741 |

| 8 symptoms selected for screening of DMX | ≥13 (40.5%) | 0.744 | 0.694 | 0.416 | 0.903 | 0.752 |

| Mixed features | ||||||

| Total score of the DMX-12 | ≥23 (34.2%) | 0.750 | 0.676 | 0.092 | 0.984 | 0.722 |

| 4 symptoms of disruptive emotion/behavior subscale | ≥7 (24.7%) | 0.750 | 0.775 | 0.128 | 0.986 | 0.791 |

| 8 symptoms selected for screening of DMX | ≥13 (40.5%) | 0.875 | 0.615 | 0.091 | 0.991 | 0.789 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shinzato, H.; Zamami, Y.; Kondo, T. The 12-Item Self-Rating Questionnaire for Depressive Mixed State (DMX-12) for Screening of Mixed Depression and Mixed Features. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 678. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10100678

Shinzato H, Zamami Y, Kondo T. The 12-Item Self-Rating Questionnaire for Depressive Mixed State (DMX-12) for Screening of Mixed Depression and Mixed Features. Brain Sciences. 2020; 10(10):678. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10100678

Chicago/Turabian StyleShinzato, Hotaka, Yu Zamami, and Tsuyoshi Kondo. 2020. "The 12-Item Self-Rating Questionnaire for Depressive Mixed State (DMX-12) for Screening of Mixed Depression and Mixed Features" Brain Sciences 10, no. 10: 678. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10100678

APA StyleShinzato, H., Zamami, Y., & Kondo, T. (2020). The 12-Item Self-Rating Questionnaire for Depressive Mixed State (DMX-12) for Screening of Mixed Depression and Mixed Features. Brain Sciences, 10(10), 678. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10100678