Geometric Feature Enhancement for Robust Facial Landmark Detection in Makeup Paper Templates

Abstract

1. Introduction

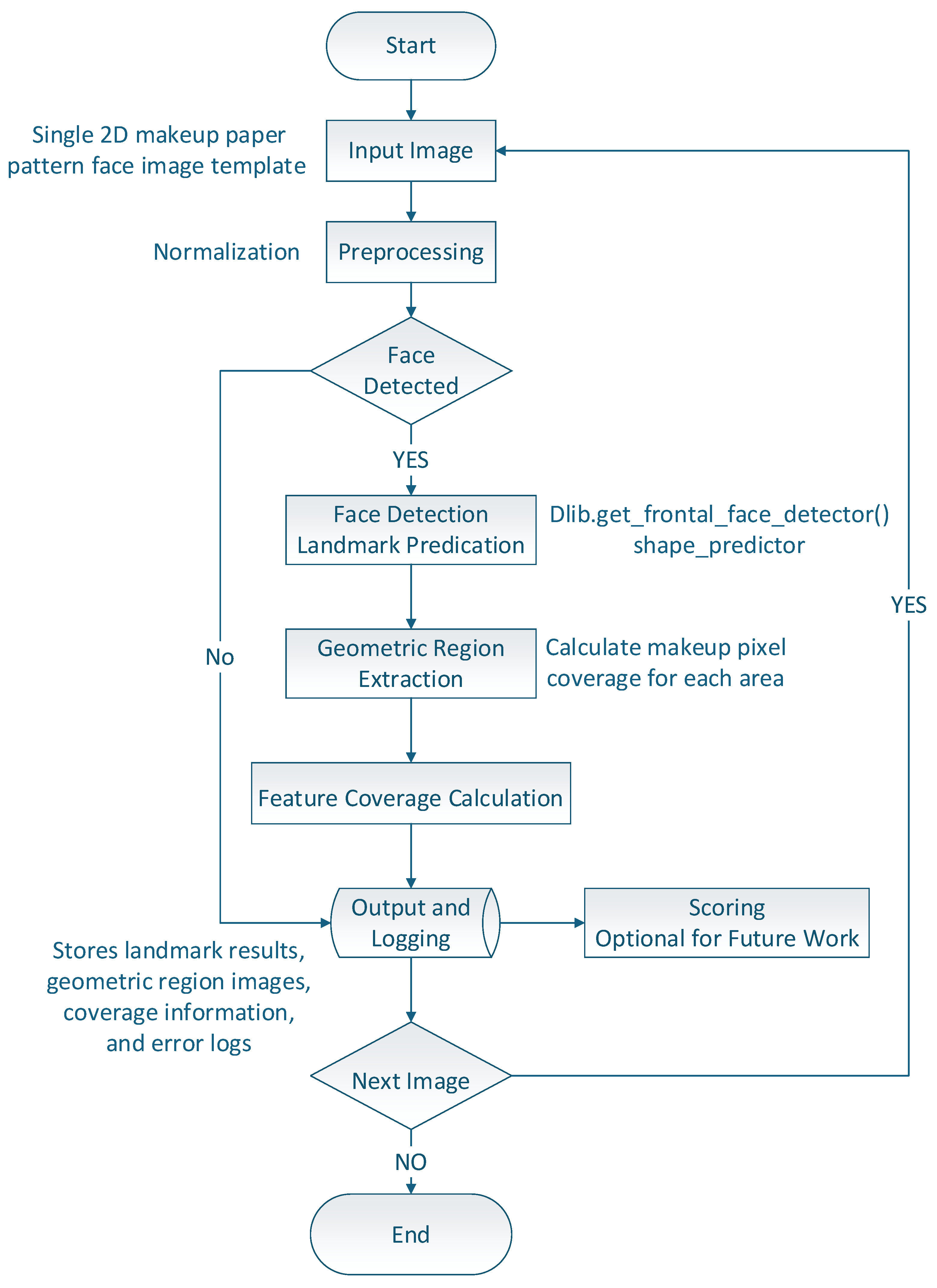

2. Materials and Methods

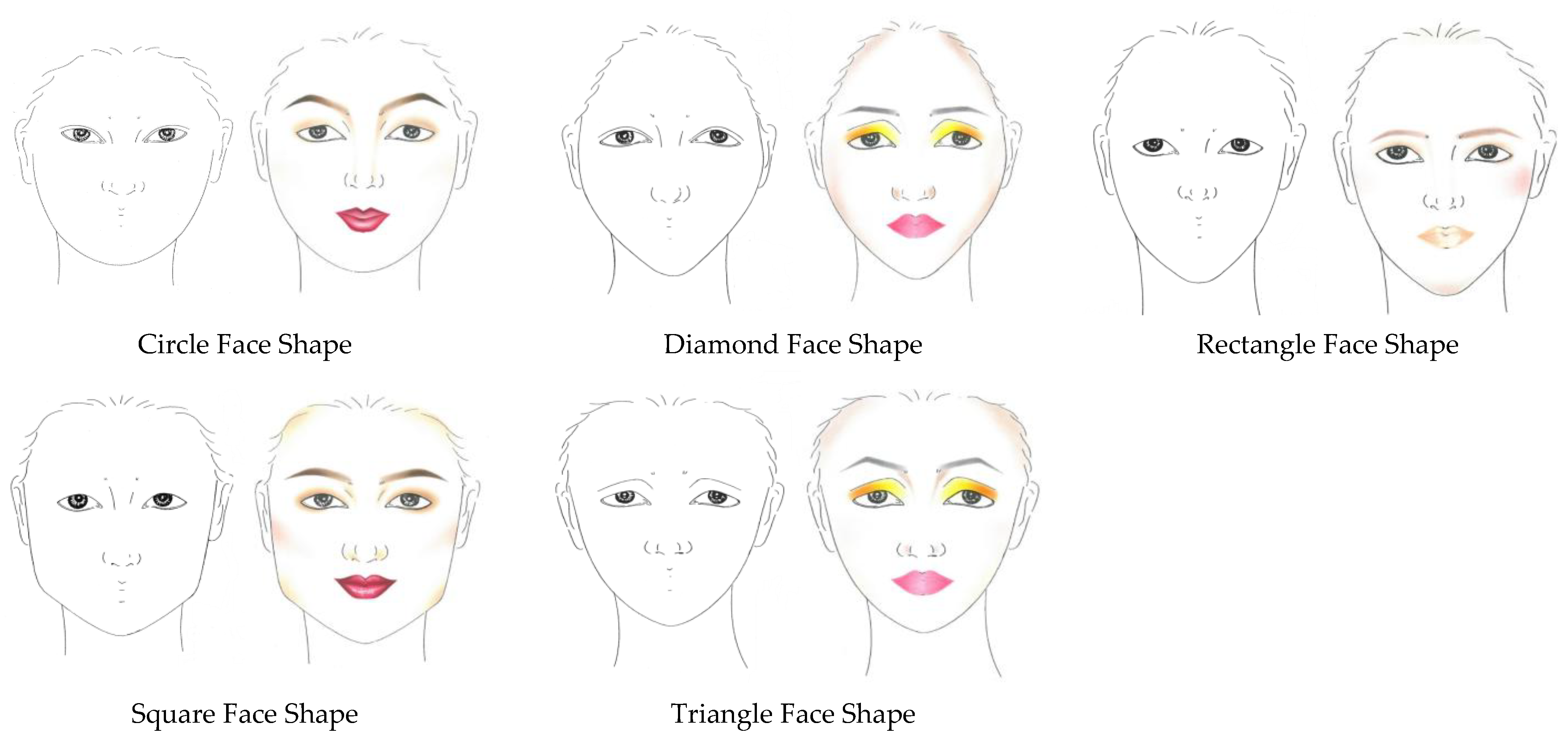

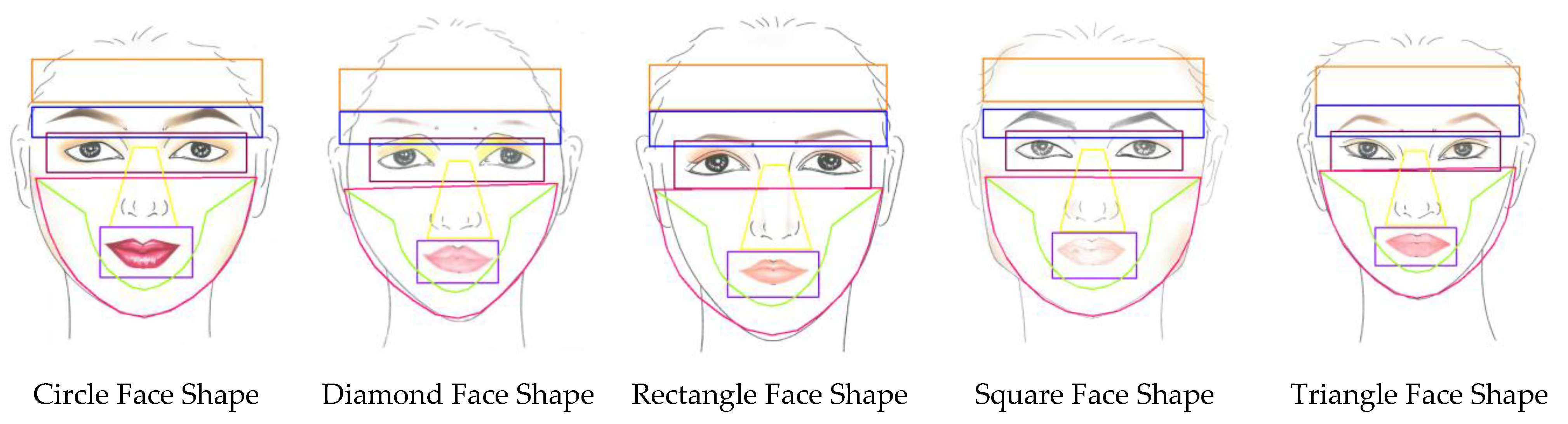

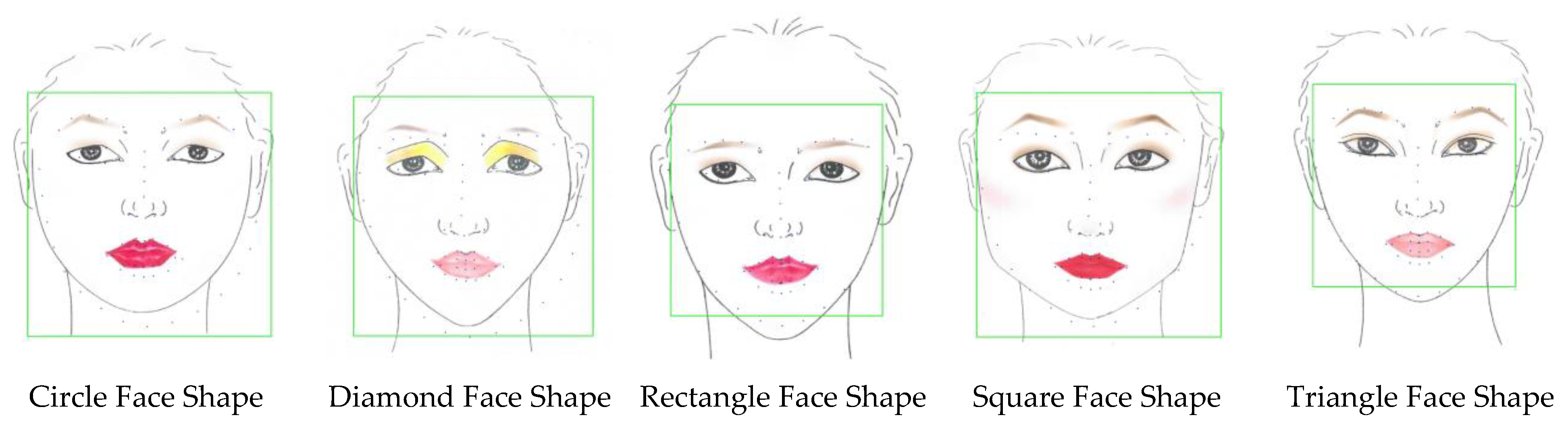

2.1. Dataset Preparation

2.2. Baseline Algorithms

2.2.1. Haar Cascade

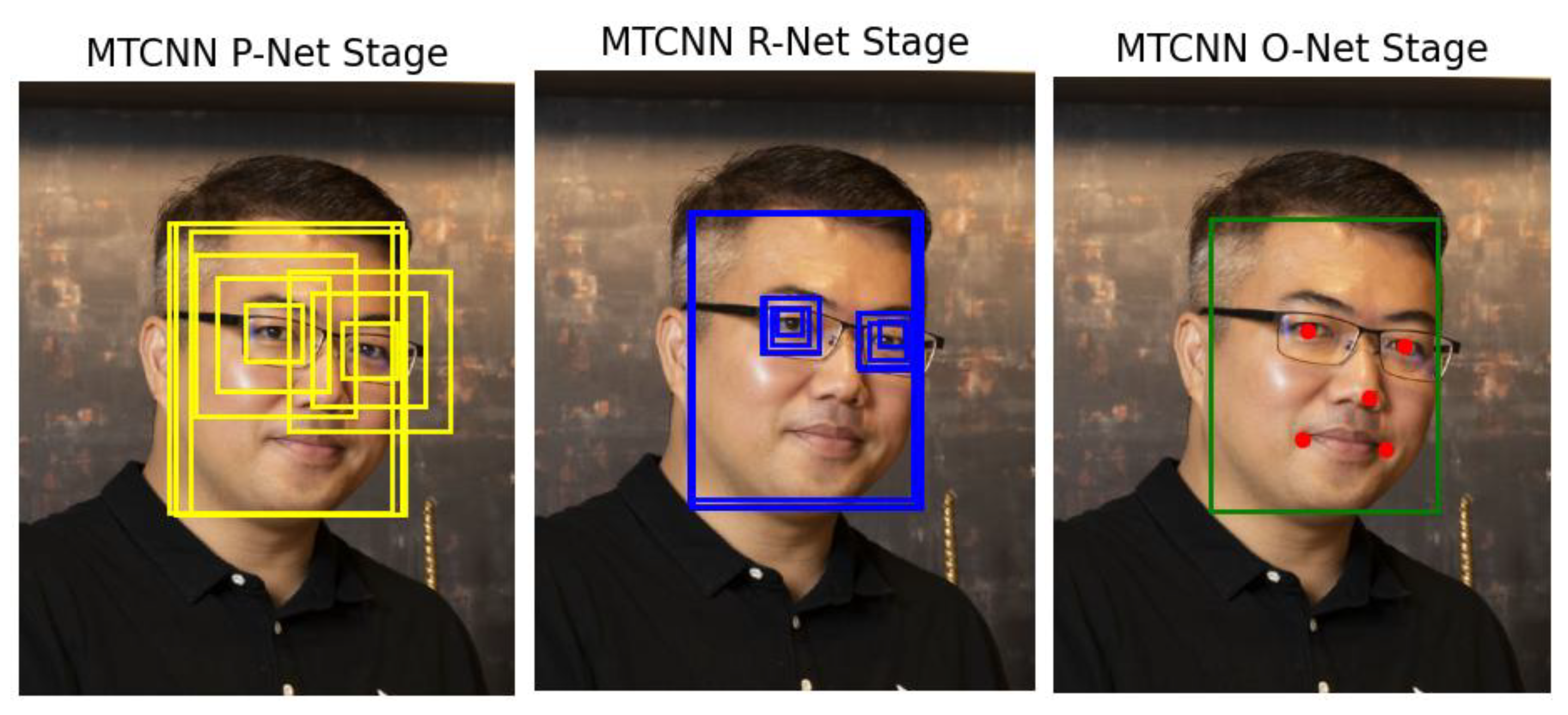

2.2.2. MTCNN-MobileNetV2

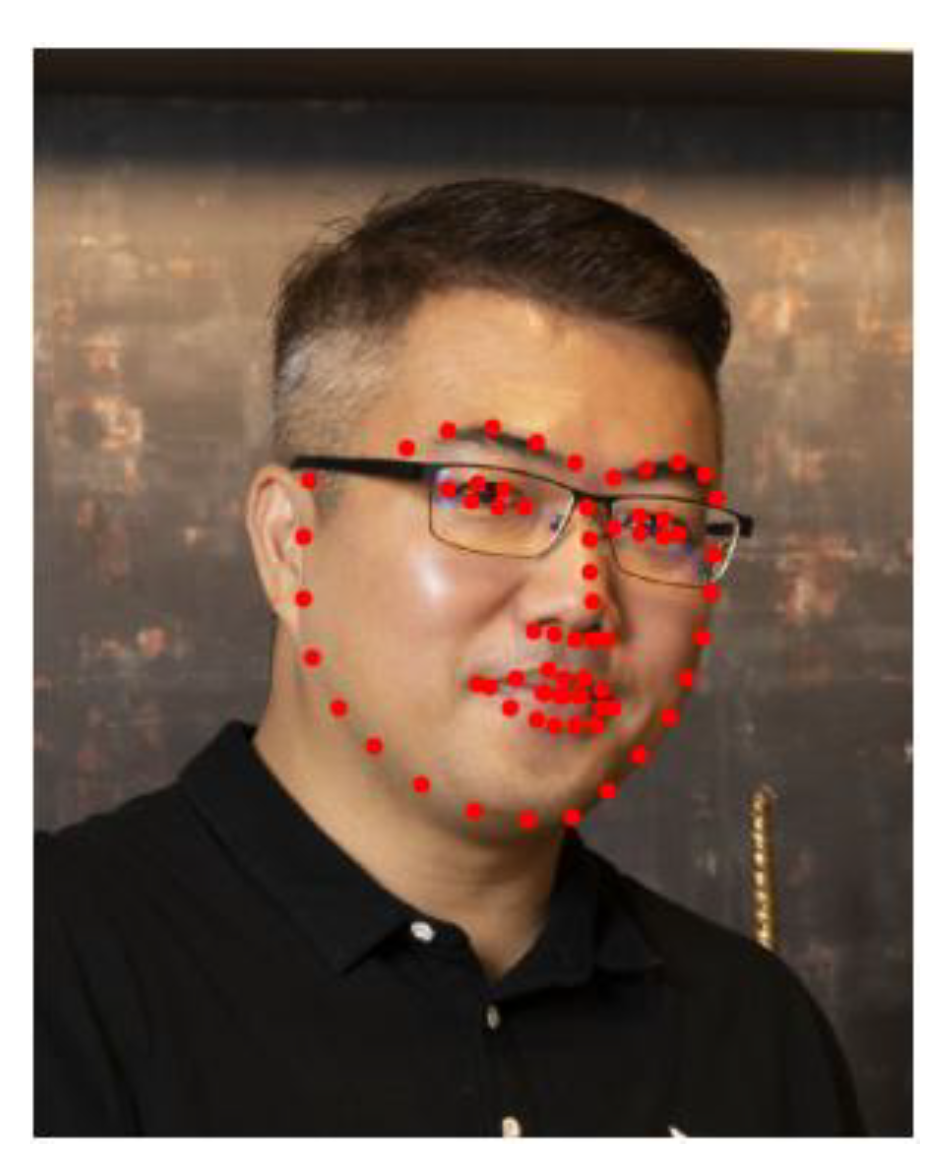

2.2.3. Dlib

2.3. Proposed Method: Geometric Feature Enhancement (GFE)

- Region SegmentationFacial landmarks are grouped into seven structural zones: forehead, eyebrows, eyes, nose, lips, cheeks, and jawline. Each region is processed independently to preserve local shape consistency.

- Proportional NormalizationInter-region distances (e.g., brow–eye height ratio, jaw width ratio, nose–lip distance) are corrected based on reference facial proportions, compensating for stylization induced distortion.

- Curvature CorrectionCubic Bézier curve fitting is applied along contour landmarks (jawline, eyebrows, lips) to smooth irregularities and restore plausible curvature.

2.4. Geometric Methods for Facial Landmark Refinement in 2D Makeup-Paper Templates

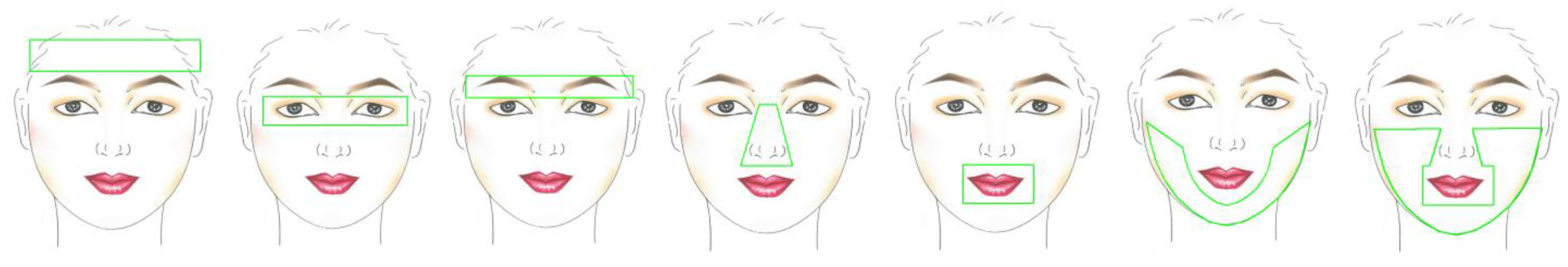

2.4.1. Proposed Geometric Features and Methods

Interocular Distance Measurement

Facial Boundary Measurement

Chin Curvature Measurement

Cheekbone Width Measurement

2.4.2. Facial Symmetry Analysis

2.4.3. Geometric Feature Enhancement (GFE)—Formal Representation

2.5. Full Detection–Refinement–Classification Pipeline (GFE-Dlib System)

2.6. Experimental Setup

- Intel i7-13700 CPU (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA)

- 32 GB RAM

- NVIDIA RTX 4050 GPU (8 GB VRAM) (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA)

- Python 3.11/Anaconda environment

- OpenCV 4.9.0

- Dlib 19.24 [15]

- batch size = 32

- adaptive learning rate = 0.001

- early stopping to prevent overfitting

- fixed random seeds for reproducibility

2.7. Evaluation Metrics

- Accuracy

- Precision

- Recall

- F1-score

- Mean Normalized Error (MNE)

3. Results

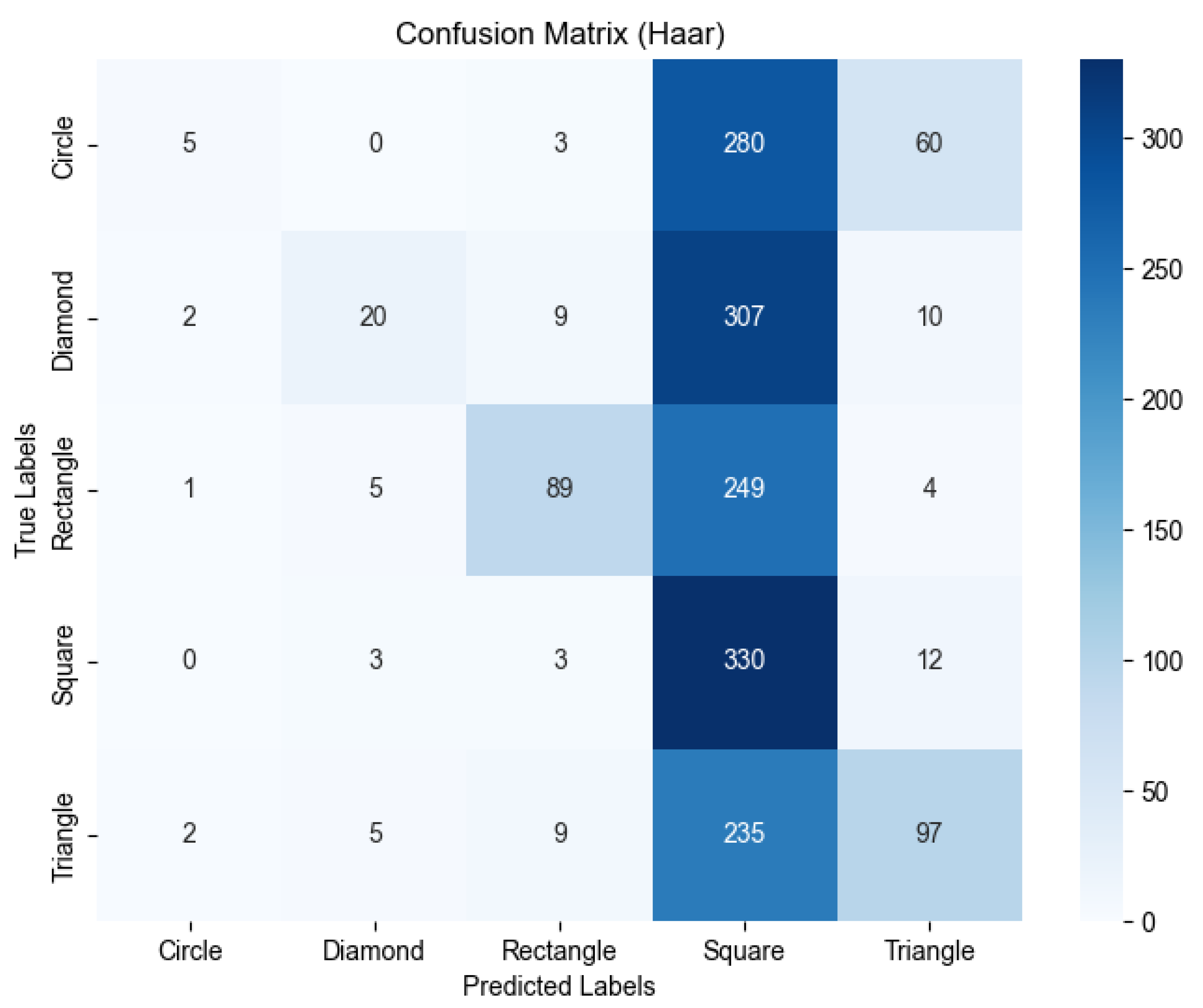

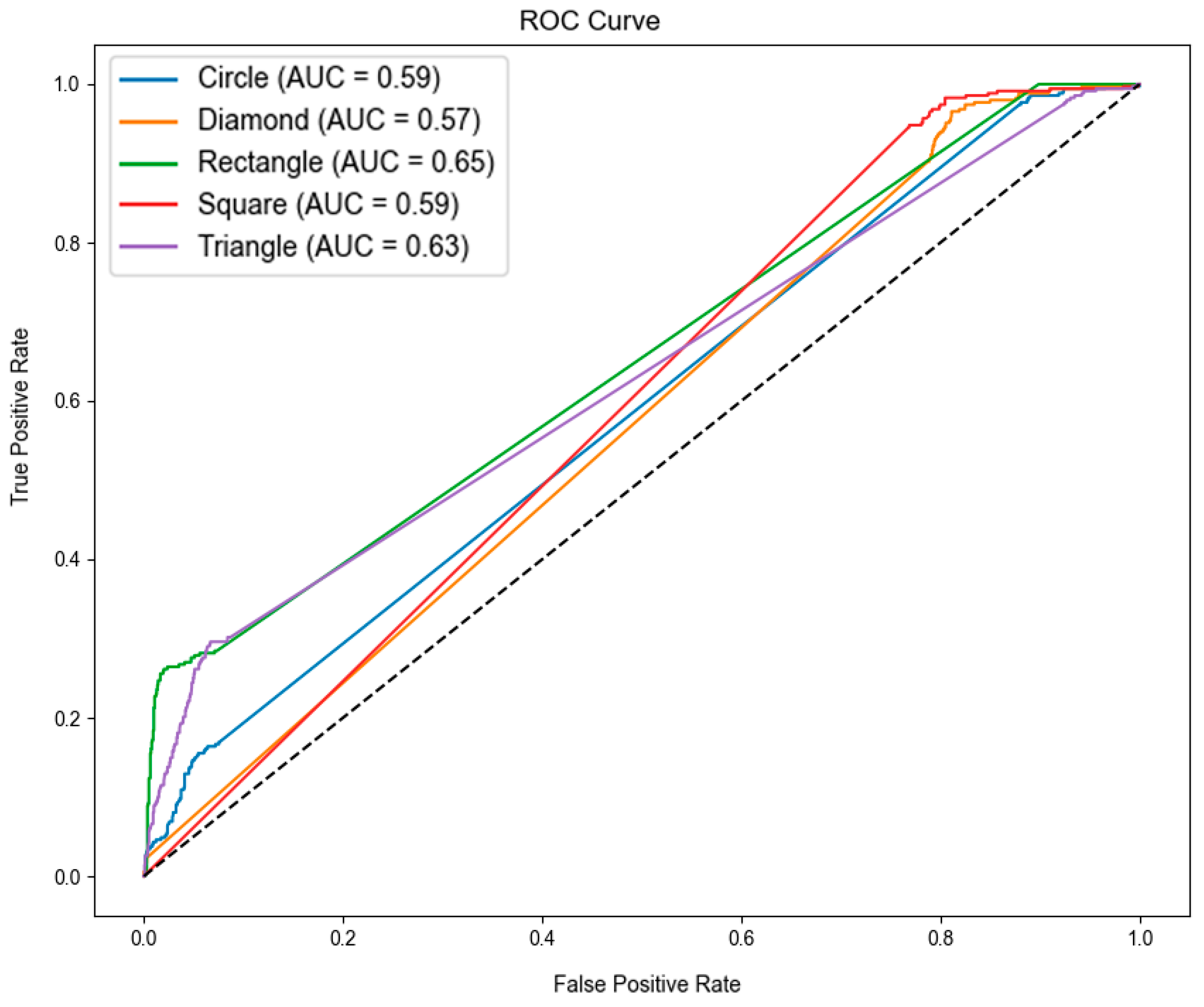

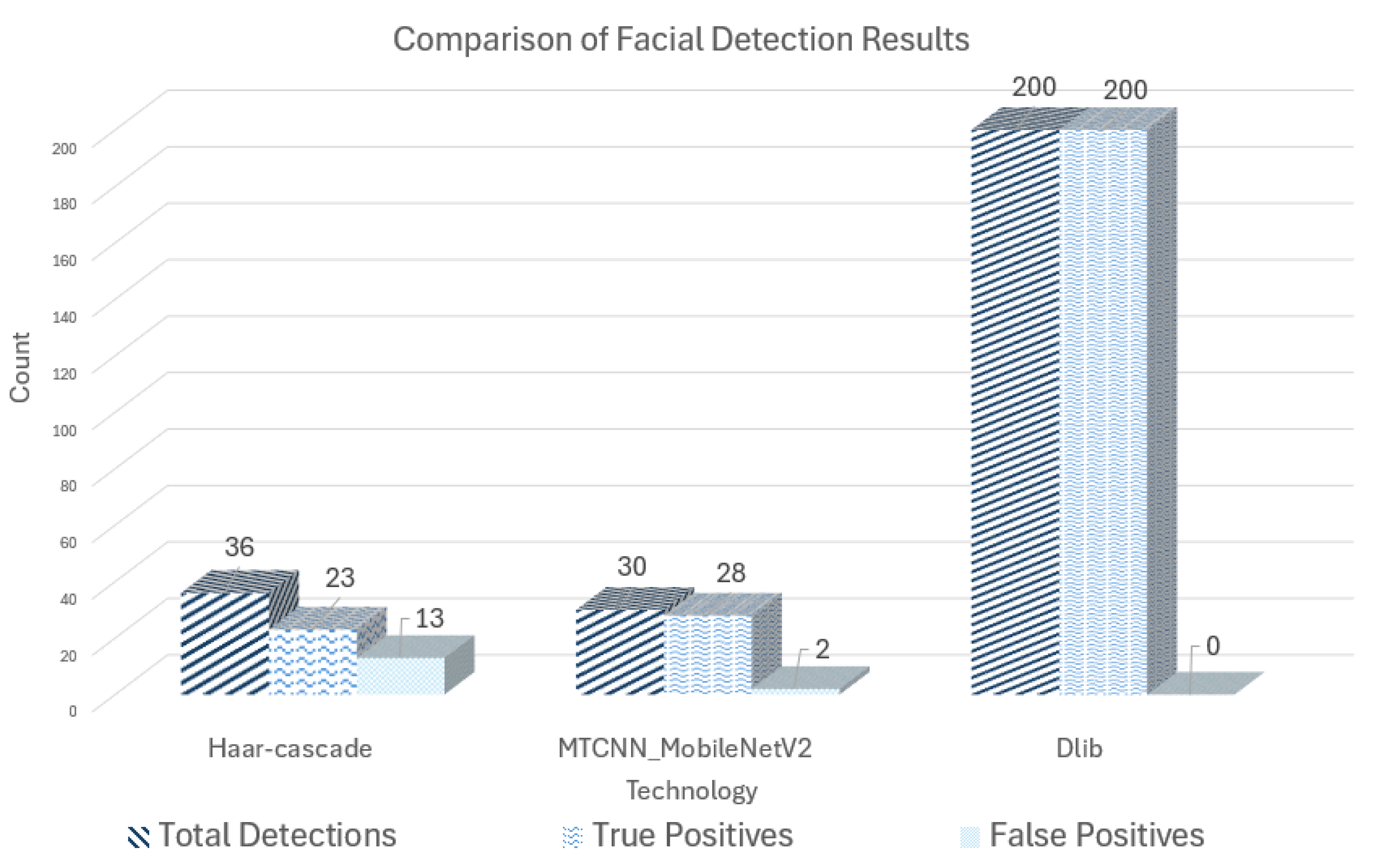

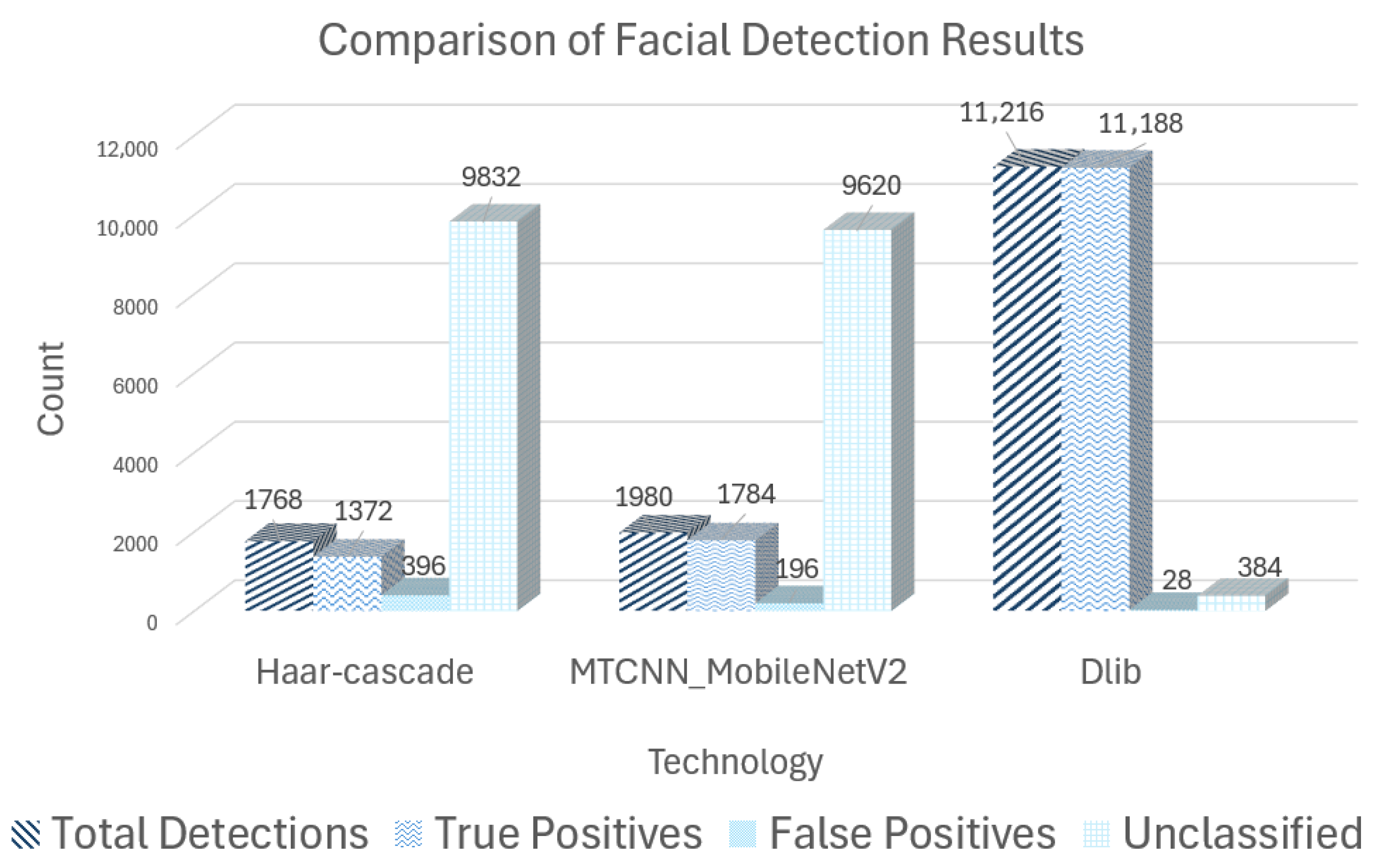

3.1. Performance of Haar Cascade

3.2. Performance of MTCNN-MobileNetV2

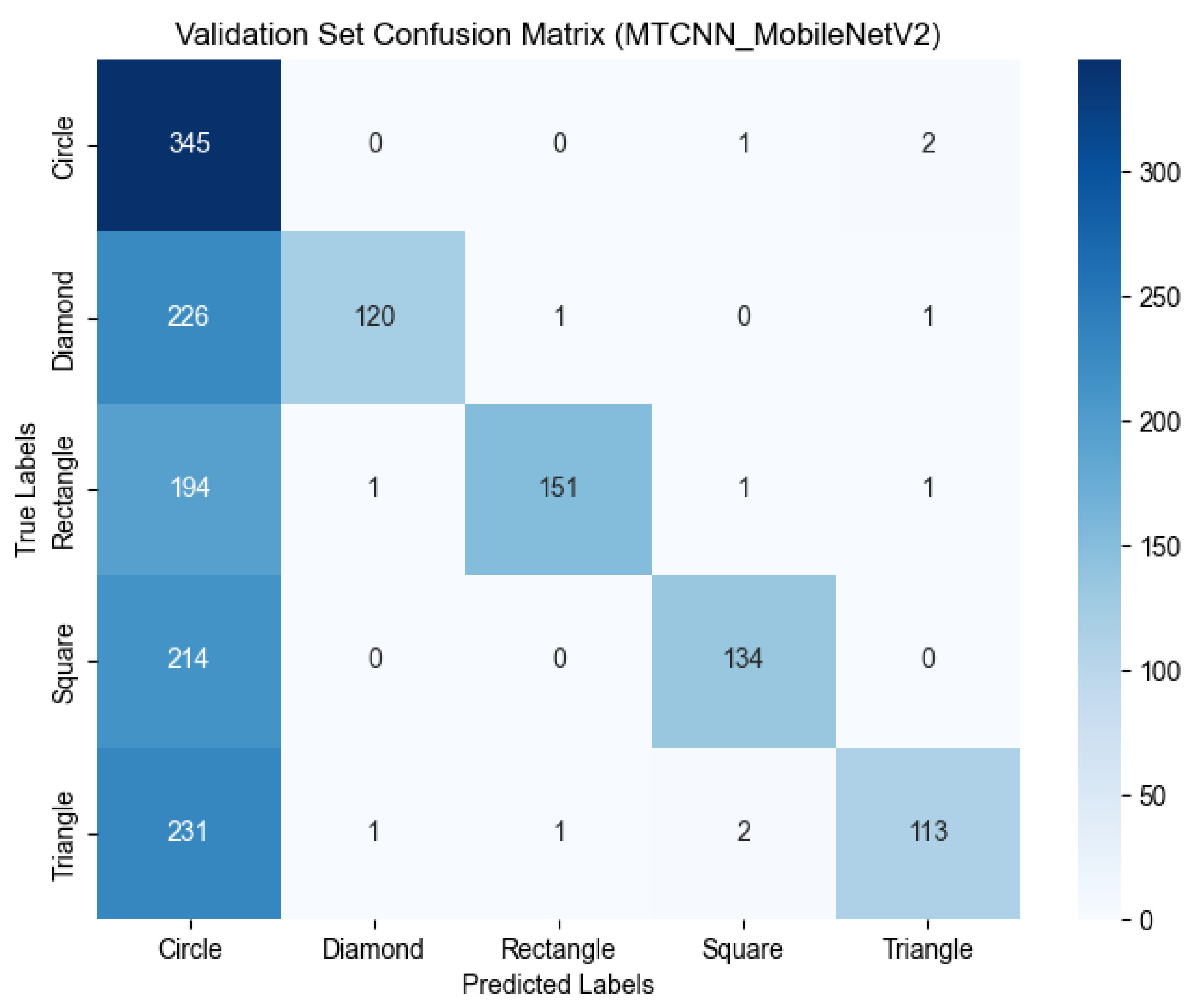

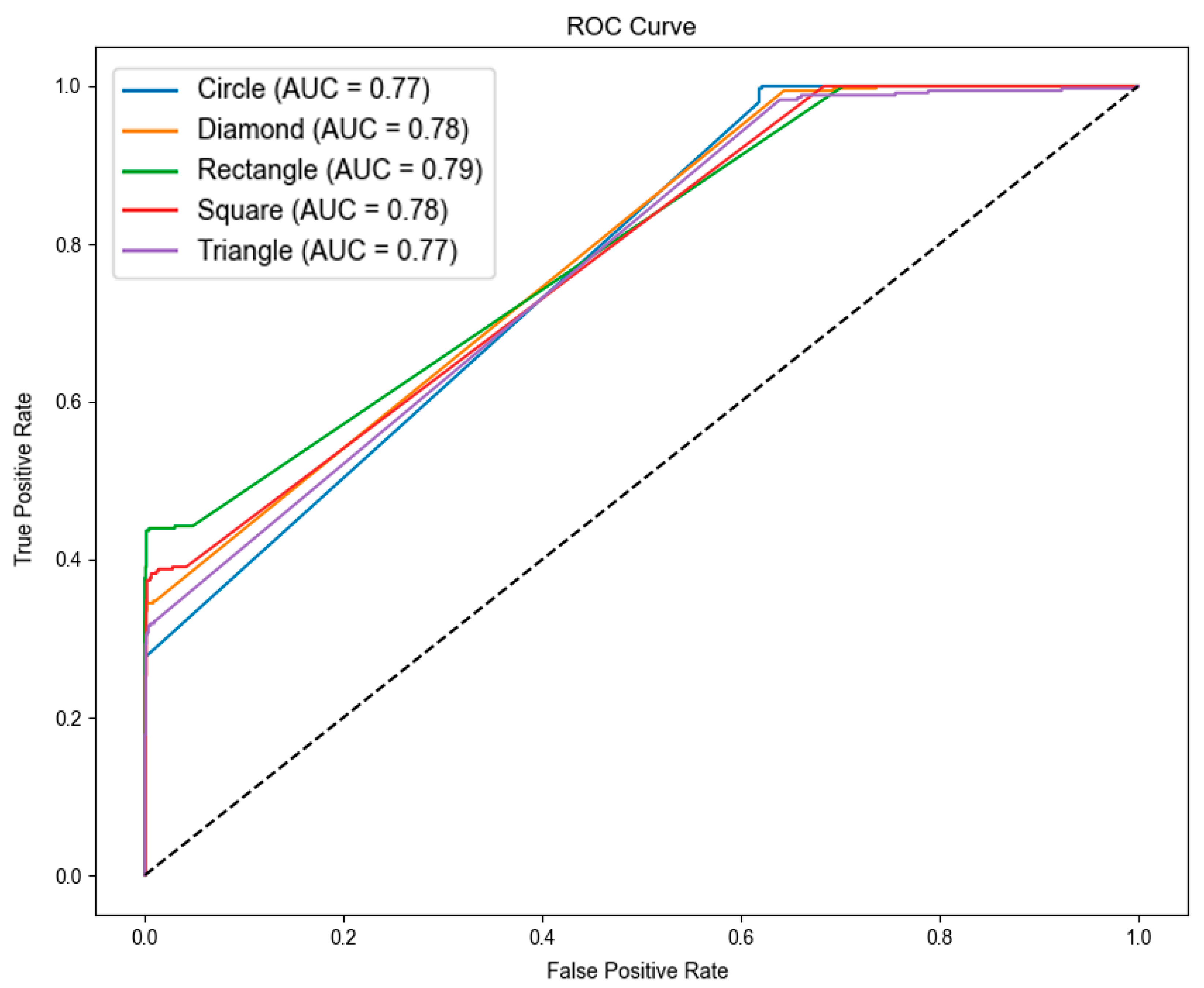

3.3. Performance of GFE-Enhanced Dlib

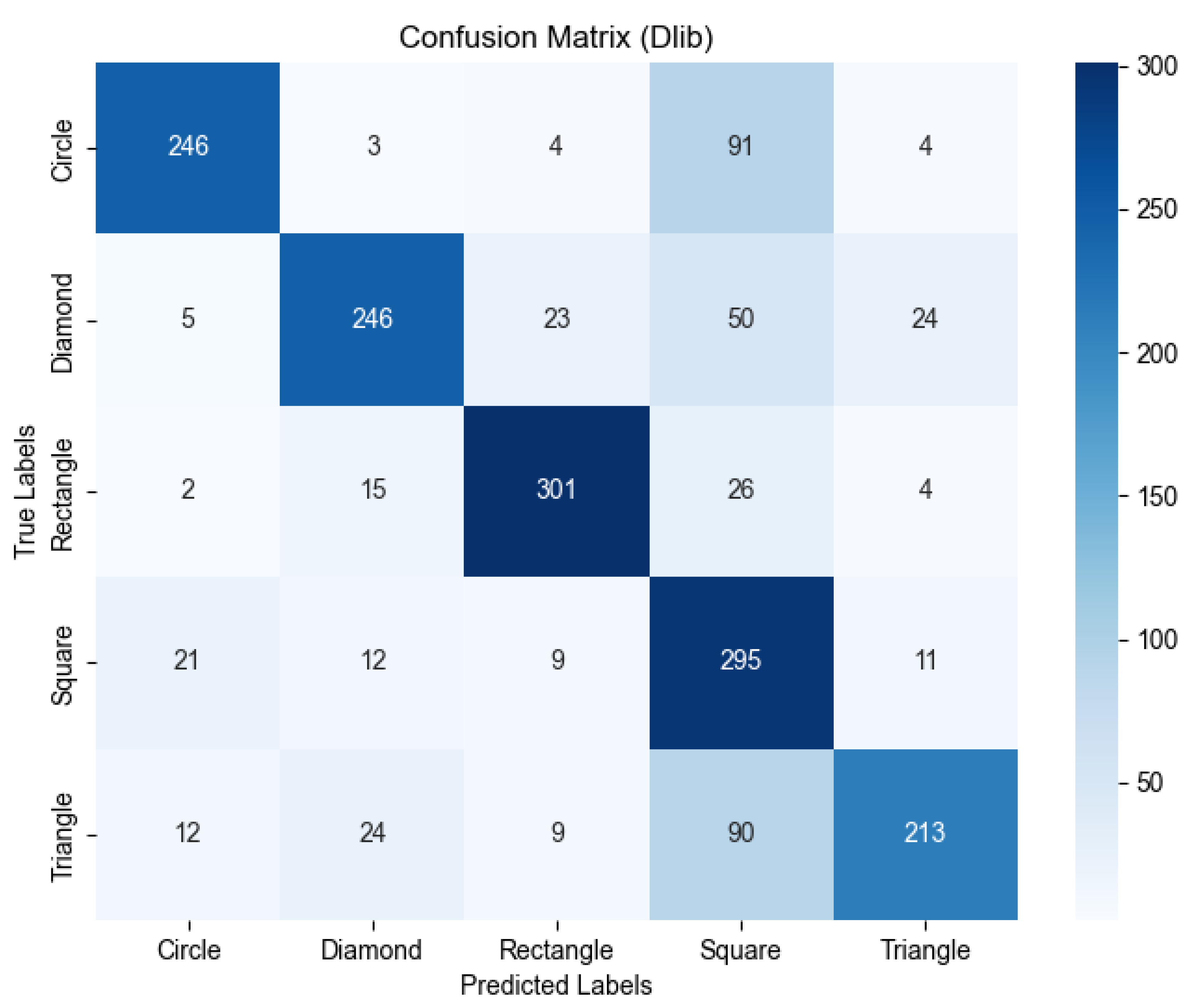

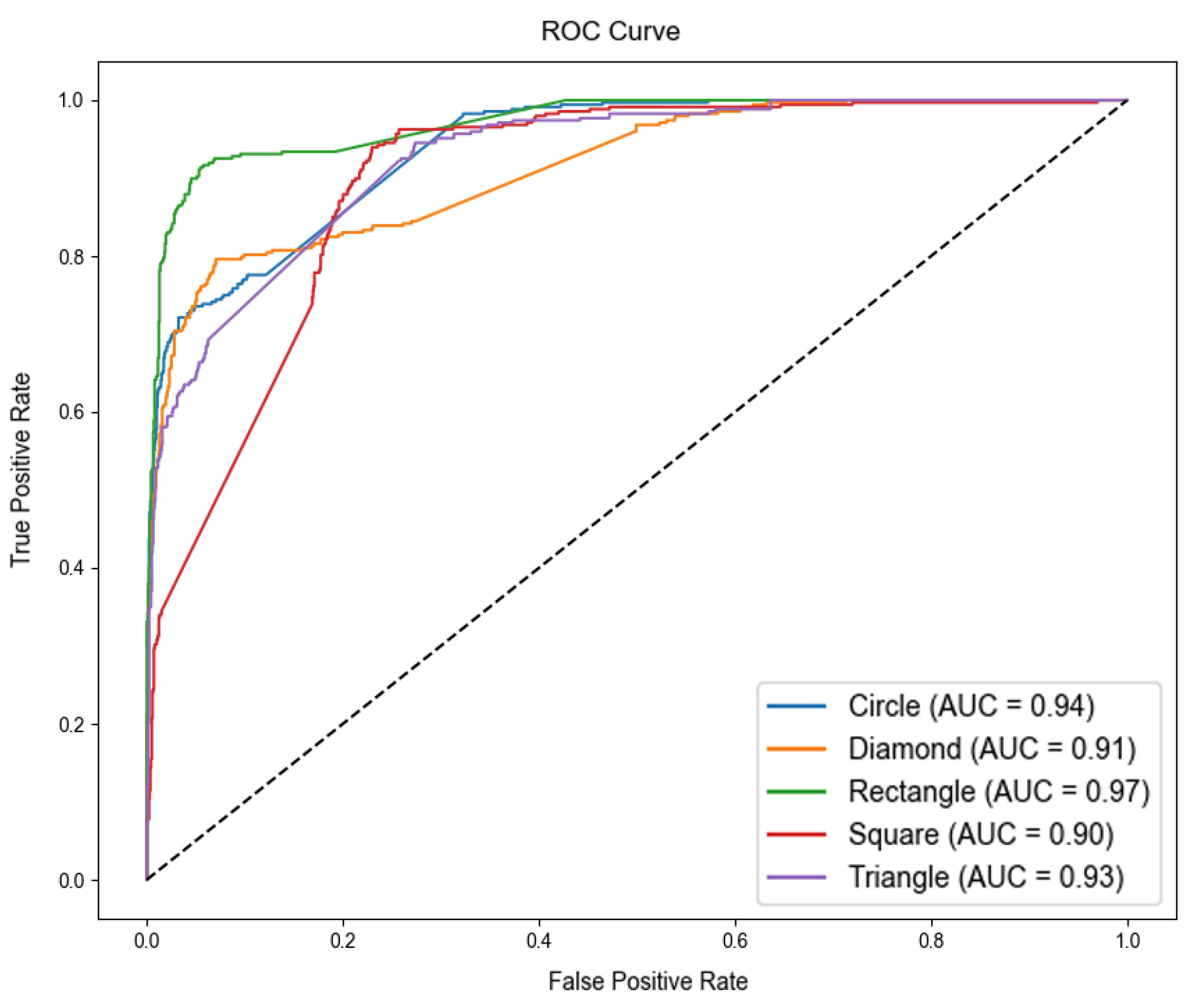

3.4. Experimental Results

4. Discussion

- Blurring (Blur): Gaussian Blur and Average Blur were applied to simulate the loss of clarity in facial boundaries, a frequent issue in hand-drawn illustrations.

- Noise Addition (Add Noise): Gaussian Noise and Salt & Pepper Noise were introduced to replicate disturbances caused by paper texture inconsistencies or uneven brush strokes.

- Contrast Reduction (Reduce Contrast): Image contrast was reduced to obscure fine facial details, mimicking issues such as unclear ink traces or inconsistent lighting.

- Random Distortion (Random Distortion): Minor Perspective Transform and Elastic Distortion were applied to simulate misalignments in facial feature placement due to artistic variations in hand-drawn templates.

4.1. Overall Model Performance Comparison

- Haar Cascade exhibited the lowest performance across all evaluation metrics, indicating its inefficacy in recognizing facial features within makeup face templates. Its recall value (<0.21) suggests a high rate of false negatives, meaning it fails to correctly detect most facial features. This result underscores the limitations of Haar Cascade in handling artistic and stylistically diverse face illustrations.

- MTCNN-MobileNetV2 achieved the highest precision (0.7232) among the evaluated methods, indicating its ability to accurately classify certain sample types. However, its low recall (0.2345) suggests that it fails to detect a substantial portion of actual facial features. This trade-off indicates that while MTCNN-MobileNetV2 performs well when it does identify a feature, it struggles with overall facial feature detection consistency in makeup face templates.

- Dlib with Geometric Feature Enhancement (GFE) outperformed the other methods by a wide margin, with accuracy reaching 0.6052. Notably, its precision (0.6087) and recall (0.6052) are both above 0.60, indicating a good balance between correctness and completeness. This demonstrates superior adaptability and robustness in facial feature recognition for the makeup templates. Overall, integrating geometric feature analysis into Dlib significantly enhanced performance, making it a more reliable approach for artistic facial illustrations.

4.2. GFE Performance by Face Shape

- For Haar Cascade, the accuracy on Circle and Diamond shapes was 0%, indicating a failure to correctly identify any sample of those shapes. It performed somewhat better on Square-shaped faces (33.41% accuracy), but overall, this method was unable to effectively recognize facial features in the makeup template images.

- MTCNN-MobileNetV2 showed the best result on Circle-shaped faces (34.28% accuracy), but its accuracy dropped sharply for Rectangle (8.79%) and Triangle (7.12%) shapes. This suggests that MTCNN-MobileNetV2 has difficulty handling the highly exaggerated or abstract features in certain hand-drawn face shapes.

- Dlib with Geometric Feature Enhancement (GFE) approach achieved the highest accuracy on all face shapes, demonstrating consistently strong performance even on blurred samples. In particular, it handled Rectangle (77.72%) and Diamond (60.78%) shapes very well—far exceeding the other methods’ accuracies on those shapes—suggesting that Dlib + GFE is especially effective for face shapes with clear geometric structures. Overall, these results highlight the GFE-based approach’s superior adaptability and robustness on stylized makeup face templates.

4.3. Key Insights from Experimental Results

4.4. Comparison with Previous Studies

4.5. Contributions of This Study

- A comprehensive evaluation of classic and modern face detectors on stylized, hand-drawn makeup templates, providing one of the first comprehensive large-scale comparisons in this domain.

- The development of a geometric feature enhancement (GFE) module that improves landmark stability by applying proportion-based corrections and curvature adjustments across seven semantic facial regions.

- Demonstrating significant performance gains of the GFE-enhanced Dlib model on both the original and augmented datasets, which consistently outperforms Haar Cascade and MTCNN-MobileNetV2.

- A stratified analysis by face shape, revealing how geometric structure influences recognition performance under stylization.

- A technical foundation for automated scoring systems in beauty skill education, offering pathways to standardized evaluation, instructor feedback tools, and potential formative assessment interfaces.

4.6. Limitations

4.7. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GFE | Geometric Feature Enhancement |

| Dlib | Dlib Facial Landmark Detection Library |

| MTCNN | Multi-Task Cascaded Convolutional Neural Network |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| MNE | Mean Normalized Error |

| FP | False Positive |

| TP | True Positive |

| FN | False Negative |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

Appendix A

| Algorithm A1. Geometric Feature Enhancement (GFE) Procedure |

| Input: L—initial 68-point landmark predictions Output: L*—refined landmark set after geometric enhancement Step 1: Region Segmentation 1.1 Group landmarks into semantic regions R = {forehead, eyebrows, eyes, nose, lips, cheeks, jawline}. Step 2: Proportional Normalization 2.1 Compute structural ratios: –brow–eye height –nose–lip distance –cheekbone width –chin depth 2.2 Normalize each region to reference geometric proportions. Step 3: Curvature Correction 3.1 Fit cubic Bézier curves along eyebrow, lip, and jawline contours. 3.2 Adjust outlier points toward the smoothed curve paths. Return: L* |

| Algorithm A2. Full Detection–Refinement–Classification Pipeline |

| Input: I—hand-drawn face template M_det—face detector (Haar, MTCNN_MobileNetV2, or original Dlib) M_lmk—Dlib 68-point landmark predictor GFE()—geometric enhancement module (Algorithm A1) M_cls—classifier for face-shape prediction Output: y_pred—predicted face-shape label L*—refined landmark set Step 1: Preprocessing 1.1 Convert image to grayscale and normalize. 1.2 Apply brightness/contrast correction. 1.3 Resize for detector compatibility. Step 2: Face Detection 2.1 Perform detection using M_det. 2.2 If detection fails → return unclassified. Step 3: Landmark Initialization 3.1 Crop detected face region. 3.2 Predict initial 68 landmarks with M_lmk. 3.3 Segment landmarks into structural facial regions. Step 4: Geometric Enhancement 4.1 Apply GFE to obtain refined landmarks L*. Step 5: Feature Extraction 5.1 Compute geometric descriptors: –interocular distance –boundary ratios –chin curvature –cheekbone width –global symmetry index 5.2 Construct feature vector F. Step 6: Shape Classification 6.1 Predict face-shape label: y_pred = M_cls(F). 6.2 Return y_pred and L*. |

References

- Virakul, S. Makeup: A Genderless Form of Artistic Expression Explored by Content Creators and Their Followers. J. Stud. Res. 2023, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemtou, E. Subjectivity in Art History and Art Criticism. Rupkatha J. Interdiscip. Stud. Humanit. 2010, 2, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, J.; Pineda, G.G.; Pineda, V.G.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Arcila-Diaz, J.; de la Puente, R.T. Using machine learning to predict artistic styles: An analysis of trends and the research agenda. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egon, K.; Potter, K.; Lord, M.L. AI in Art and Creativity: Exploring the Boundaries of Human–Machine Collaboration. OSF Preprint 2023, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugail, H.; Stork, D.G.; Edwards, H.; Seward, S.C.; Brooke, C. Deep Transfer Learning for Visual Analysis and Attribution of Paintings by Raphael. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Mithun, N.C.; Rudolph, C.; Roy-Chowdhury, A.K. Deep Learning Based Identity Verification in Renaissance Portraits. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), San Diego, CA, USA, 23–27 July 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Qiao, Y. Joint Face Detection and Alignment Using Multitask Cascaded Convolutional Networks. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2016, 23, 1499–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Guo, J.; Ververas, E.; Kotsia, I.; Zafeiriou, S. RetinaFace: Single-Shot Multi-Level Face Localisation in the Wild. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 5202–5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nuimi, A.M.; Mohammed, G.J. Face Direction Estimation based on Mediapipe Landmarks. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Conference on Contemporary Information Technology and Mathematics (ICCITM), Mosul, Iraq, 25–26 August 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhi, O.M.; Vedaldi, A.; Zisserman, A. Deep Face Recognition. In Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC), Swansea, UK, 7–10 September 2015; Xie, X., Jones, M.W., Tam, G.K.L., Eds.; BMVA Press: Malvern, UK, 2015; pp. 41.1–41.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, T. Aesthetic Visual Quality Assessment of Paintings. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2009, 3, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, X.; Bai, R.; Li, W. Image Aesthetic Assessment Based on Attention Mechanisms and Holistic Nested Edge Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 Asia Conference on Advanced Robotics, Automation, and Control Engineering (ARACE), Qingdao, China, 26–28 August 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-T.; Lee, C.; Kim, C.-S. Property-Specific Aesthetic Assessment with Unsupervised Aesthetic Property Discovery. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 114349–114362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Y.; Wang, C.; Huang, K. Visual aesthetic quality assessment with a regression model. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Quebec City, QC, Canada, 27–30 September 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1583–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlib C++ Library. Available online: http://dlib.net (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Kazemi, V.; Sullivan, J. One millisecond face alignment with an ensemble of regression trees. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1867–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroff, F.; Kalenichenko, D.; Philbin, J. FaceNet: A unified embedding for face recognition and clustering. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Yu, S.; Peng, H.; Li, Y.-R.; Zhang, J. Detect Faces Efficiently: A Survey and Evaluations. IEEE Trans. Biom. Behav. Identity Sci. 2022, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Sharma, D. Comparative Study of Face Detection Using Cascaded Haar, Hog and MTCNN Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Advancement in Electronics & Communication Engineering (AECE), Ghaziabad, India, 23–24 November 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, P.; Jones, M. Rapid object detection using a boosted cascade of simple features. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2001, Kauai, HI, USA, 8–14 December 2001; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2001; p. I. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Luo, J.; Gao, W. Research on Face Detection Technology Based on MTCNN. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computer Network, Electronic and Automation (ICCNEA), Xi’an, China, 25–27 September 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areeb, Q.M.; Imam, R.; Fatima, N.; Nadeem, M. AI Art Critic: Artistic Classification of Poster Images using Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Data Analytics for Business and Industry (ICDABI), Sakheer, Bahrain, 25–26 October 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; He, Z.; Peng, B.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J. 3D-Aware Adversarial Makeup Generation for Facial Privacy Protection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 13438–13453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, R.; Madhushan, N.; Jeeva, A.; Darshani, D.; Subasinghe, A.; Silva, B.N.; Wijesinghe, L.P.; Wijenayake, U. Current Trends in Human Pupil Localization: A Review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 115836–115853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, X.; Morvan, J.-M.; Chen, L. Improving Shadow Suppression for Illumination Robust Face Recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 41, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Hou, J. Makeup Removal for Face Verification Based Upon Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 6th International Conference on Signal and Image Processing (ICSIP), Nanjing, China, 22–24 October 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmashree, G.; Kotegar, K.A. Skin Segmentation-Based Disguised Face Recognition Using Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 51056–51072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hirota, K.; Ma, J.; Jia, Z.; Dai, Y. Facial Expression Recognition Using Hybrid Features of Pixel and Geometry. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 18876–18889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, B.-G.; Roy, P.P.; Jeong, D.-M. Efficient Facial Expression Recognition Algorithm Based on Hierarchical Deep Neural Network Structure. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 41273–41285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, A.G.; Muniyandi, R.C.; Usman, O.L.; Singh, H.K.R. A Hybrid Method of Enhancing Accuracy of Facial Recognition System Using Gabor Filter and Stacked Sparse Autoencoders Deep Neural Network. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Xu, Z.; Li, Z.; Cai, Y.; Han, M.; Ji, Y. An Intelligent Scoring Method for Sketch Portrait Based on Attention Convolution Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Smartworld, Ubiquitous Intelligence & Computing, Scalable Computing & Communications, Digital Twin, Privacy Computing, Metaverse, Autonomous & Trusted Vehicles (SmartWorld/UIC/ScalCom/DigitalTwin/PriComp/Meta), Haikou, China, 15–18 December 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreya, R.; Mulgund, A.P.; Hiremath, S.; A, S.H.; Koundinya, A.K. Comparative Analysis of Traditional and Machine Learning Based Face Recognition Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Data, Decision and Systems (ICDDS), Mangaluru, India, 1–2 December 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, T.A.; Balasubramanian, V.N.; Jawahar, C.V. Canonical Saliency Maps: Decoding Deep Face Models. IEEE Trans. Biom. Behav. Identity Sci. 2021, 3, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eman, M.; Mahmoud, T.M.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Abd El-Hafeez, T. Innovative Hybrid Approach for Masked Face Recognition Using Pretrained Mask Detection and Segmentation, Robust PCA, and KNN Classifier. Sensors 2023, 23, 6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saabia, A.A.R.; El-Hafeez, T.A.; Zaki, A.M. Face Recognition Based on Grey Wolf Optimization for Feature Selection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems and Informatics (AISI), Cairo, Egypt, 1–3 September 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspect | General Facial Recognition | 2D Makeup Paper Template Recognition |

|---|---|---|

| Data Dimension | 3D images (with depth information) | 2D planar images |

| Texture Information | Rich features such as skin details, pores, and wrinkles | Relies on hand-drawn lines and color expressions |

| Impact of Lighting Variations | Shadows and lighting variations assist in depth estimation | Fixed lighting; shadows cannot provide depth cues |

| Dynamic Features | Facial expressions, lip movements, and other micro-dynamics | Completely static, unable to capture facial dynamics |

| Feature Stability | Standardized landmark detection via deep learning | Affected by drawing errors; facial proportions may be inaccurate |

| Color Consistency | Uniform skin tones, influenced by environmental lighting | Dependent on drawing tools (e.g., pencils, watercolor, markers), leading to potential color inconsistencies |

| Category | Training Set | Validation Set | Test Set | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circle | 1280 | 480 | 560 | 2320 |

| Diamond | 1280 | 480 | 560 | 2320 |

| Rectangle | 1280 | 480 | 560 | 2320 |

| Square | 1280 | 480 | 560 | 2320 |

| Triangle | 1280 | 480 | 560 | 2320 |

| Total | 6400 | 2400 | 2800 | 11,600 |

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| P | The complete set of facial landmarks, consisting of 68 two-dimensional coordinate points. |

| {p1, p2, …, p68} | Elements of the set P, representing individual facial feature points from point 1 to 68. |

| pi | A single facial landmark point (e.g., eye corner, nose tip, mouth corner), where i = 1 to 68. |

| ∈ | Mathematical symbol meaning “is an element of” or “belongs to.” |

| ℝ2 | Denotes the 2D Cartesian coordinate space: each point has coordinates (xi, yi). |

| Deye | Interocular distance: Euclidean distance between eye corner landmarks p36 and p45. |

| rf | Facial aspect ratio: Width-to-height ratio based on selected facial landmarks. |

| wf, ℎf | Facial width and height, respectively, used in computing rf and symmetry metrics. |

| Rsym | Facial symmetry index based on normalized deviation of paired horizontal landmarks. |

| xiL, xiR | Horizontal coordinates of symmetric landmark pairs (left/right), used in symmetry calculation. |

| Cchin | Chin curvature index: Second derivative of vertical coordinates over a range of chin landmarks. |

| Δc | Geometric center offset: Distance between average landmark center and ideal facial center. |

| cideal | Ideal geometric center from a template face, used for landmark alignment comparison. |

| Seo | Overall geometric scoring function combining all metrics with weights. |

| wi | Normalized weight coefficient (wi ∈ [0, 1]) for each geometric metric, summing to 1. |

| fi(gi) | Normalization function applied to each geometric metric gi to scale into a unified score range. |

| gi | A geometric metric used in the scoring function (e.g., Deye, rf, Rsym, Cchin, Δc). |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haar | 0.3109 | 0.5319 | 0.3109 | 0.2523 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTCNN-MobileNet | 0.4960 | 0.5188 | 0.8385 | 0.4960 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dlib | 0.7477 | 0.7833 | 0.7477 | 0.7527 |

| Technology | Total Images | Total Detections | True Positives | False Positives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haar Cascade | 200 | 36 | 23 | 13 |

| MTCNN-MobileNetV2 | 200 | 30 | 28 | 2 |

| Dlib | 200 | 200 | 200 | 0 |

| Technology | Total Images | Total Detections | True Positives | False Positives | Unclassified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haar Cascade | 11,600 | 1768 | 1372 | 396 | 9832 |

| MTCNN-MobileNetV2 | 11,600 | 1980 | 1784 | 196 | 9620 |

| Dlib | 11,600 | 11,216 | 11,188 | 28 | 384 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dlib + GFE | 0.6052 | 0.6087 | 0.6052 | 0.6012 |

| MTCNN-MobileNetV2 | 0.2345 | 0.7232 | 0.2345 | 0.1372 |

| Haar Cascade | 0.2029 | 0.2601 | 0.2029 | 0.0736 |

| Face Shape | Haar Cascade | MTCNN-MobileNetV2 | Dlib + GFE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circle_R | 0.0000 | 0.3428 | 0.5619 |

| Diamond_R | 0.0000 | 0.1069 | 0.6078 |

| Rectangle_R | 0.0169 | 0.0879 | 0.7772 |

| Square_R | 0.3341 | 0.0769 | 0.5440 |

| Triangle_R | 0.0170 | 0.0712 | 0.5149 |

| Study | Key Contributions | Identified Limitations | How This Study Addresses the Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zheng et al. [31] | Sketch portrait scoring using attention-based CNN models | Focuses on sketch aesthetics; lacks stable landmark detection for stylized templates | Introduces geometric enhancement to stabilize landmark localization under stylistic distortions |

| Lyu et al. [23] | 3DAM-GAN for adversarial makeup image generation | Designed for generation/translation tasks, not for landmark analysis | Leverages geometric modeling to maintain landmark structure under stylized or occluded regions |

| Shreya et al. [32] | Comparative evaluation of face-recognition models (Haar, MTCNN, Dlib) | Tested on real-face datasets only; limited coverage of hand-drawn or stylized faces | Extends the evaluation to artistic/stylized templates and validates robustness under distortions |

| Rathnayake et al. [24] | Comprehensive review of pupil localization | Focuses on partial-region detection; lacks full-face geometric alignment | Incorporates holistic geometric reasoning to support landmark stability |

| Liu et al. [28] | Hybrid pixel–geometric models for facial expression recognition | Not optimized for stylized drawings or face-template distortion | Extends geometric modeling to handle asymmetric contours and proportion exaggeration |

| Eman et al. [34] | Mask-face recognition using PCA, RPCA, KNN | Models trained on partially occluded faces; performance unstable under abstraction | Applies geometric enhancement to mitigate structural loss in hand-drawn faces |

| Saabia et al. [35] | Feature selection using GWO with PCA and Gabor filters | Focuses on stylized abstraction but lacks landmark-level constraints | Incorporates geometric constraints to improve landmark reliability under stylized variations |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chang, C.; Fanjiang, Y.-Y.; Hung, C.-H. Geometric Feature Enhancement for Robust Facial Landmark Detection in Makeup Paper Templates. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 977. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020977

Chang C, Fanjiang Y-Y, Hung C-H. Geometric Feature Enhancement for Robust Facial Landmark Detection in Makeup Paper Templates. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):977. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020977

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Cheng, Yong-Yi Fanjiang, and Chi-Huang Hung. 2026. "Geometric Feature Enhancement for Robust Facial Landmark Detection in Makeup Paper Templates" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 977. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020977

APA StyleChang, C., Fanjiang, Y.-Y., & Hung, C.-H. (2026). Geometric Feature Enhancement for Robust Facial Landmark Detection in Makeup Paper Templates. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 977. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020977