Development of Curcumin-Loaded Nanoemulsions for Fortification and Stabilization of Dairy Beverages

Featured Application

Abstract

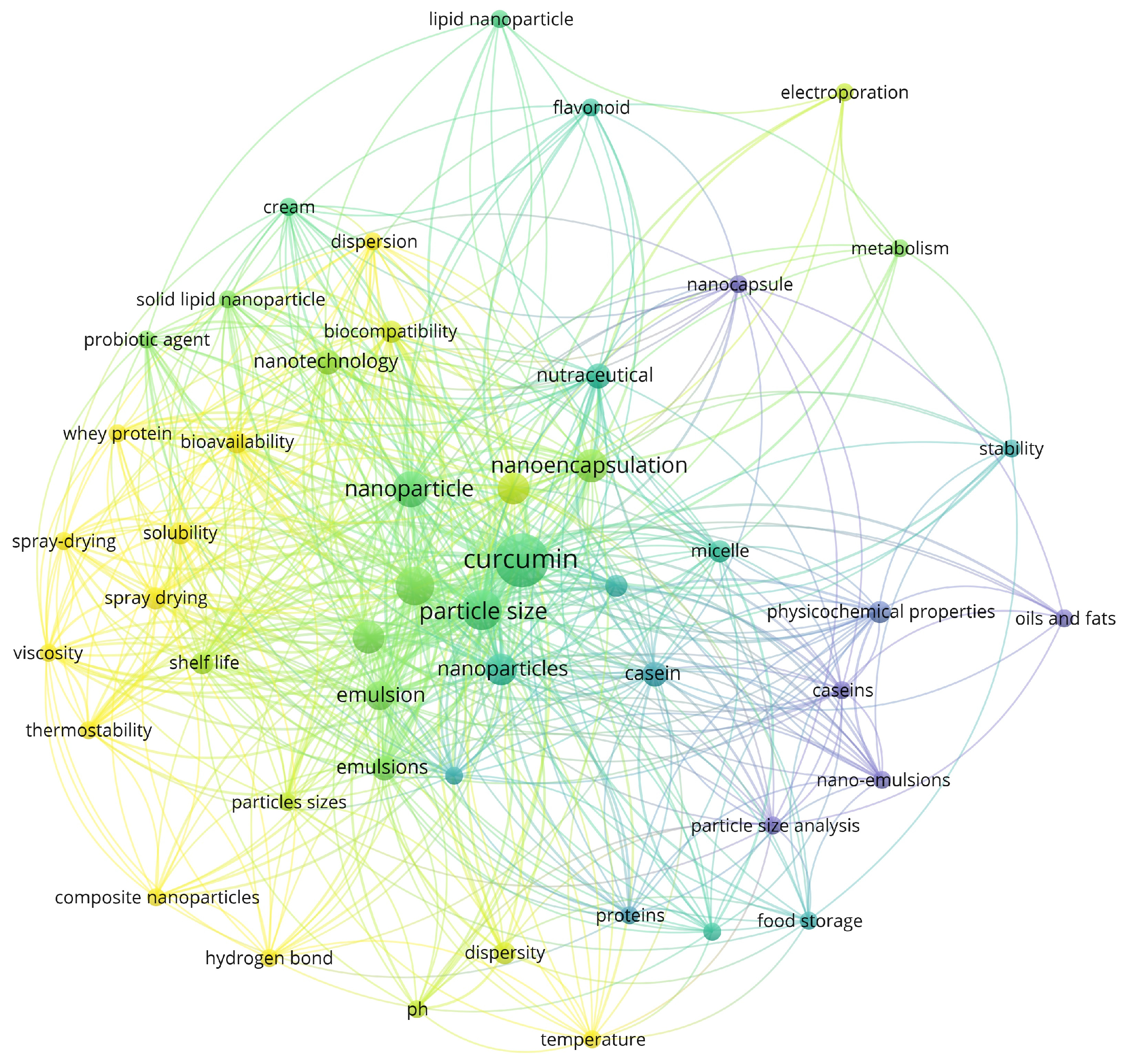

1. Introduction

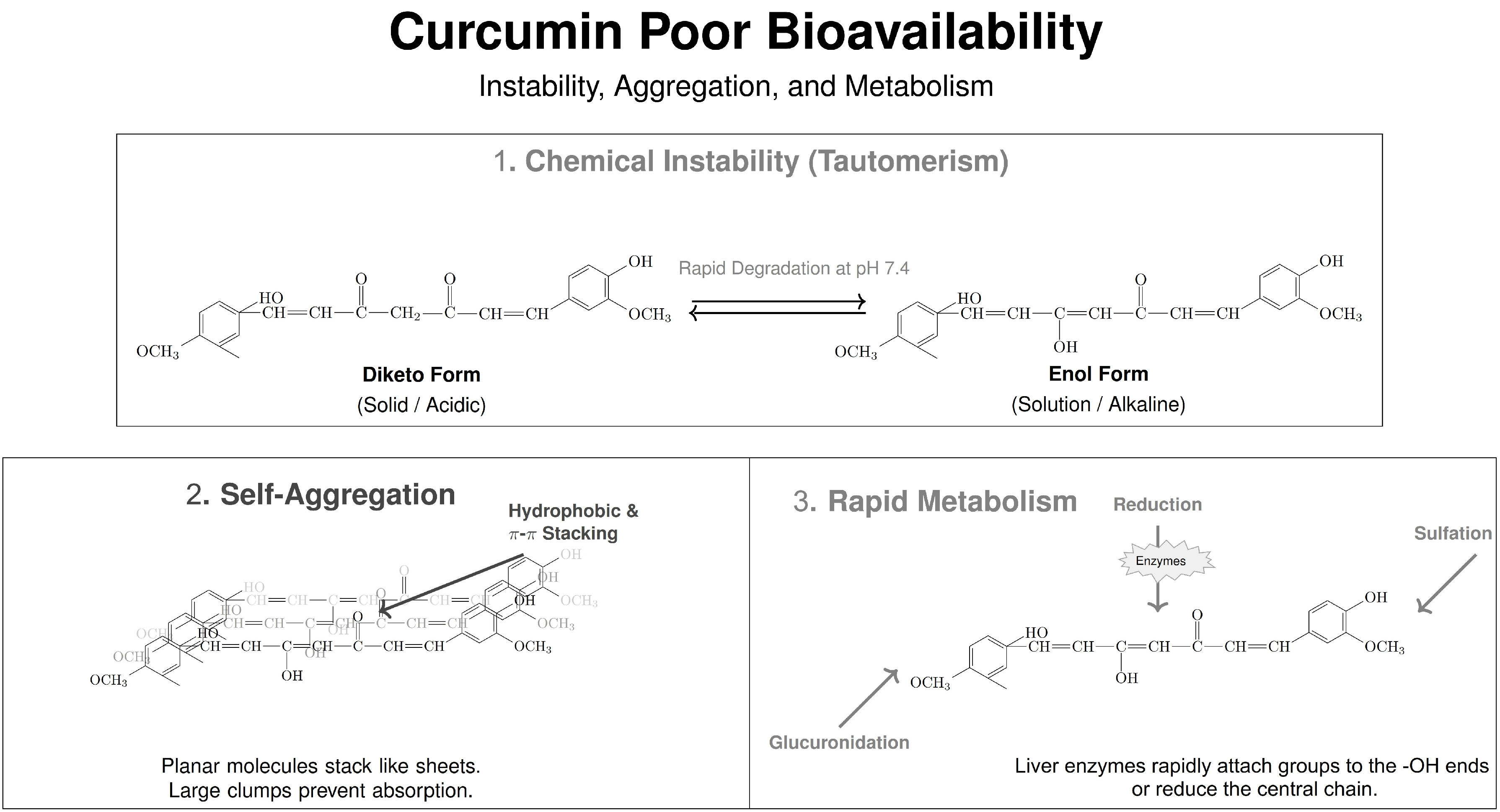

2. Curcumin and Its Functional Properties

Curcumin: Bioactivity and the Challenge of Delivery

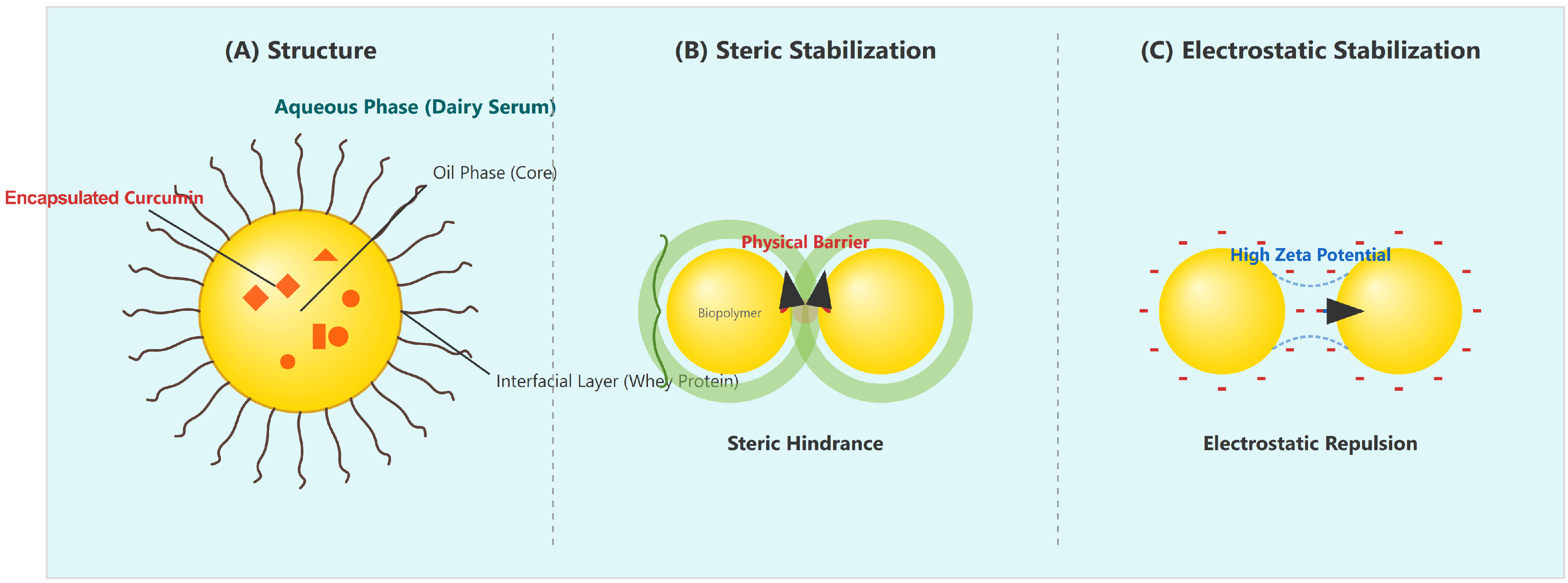

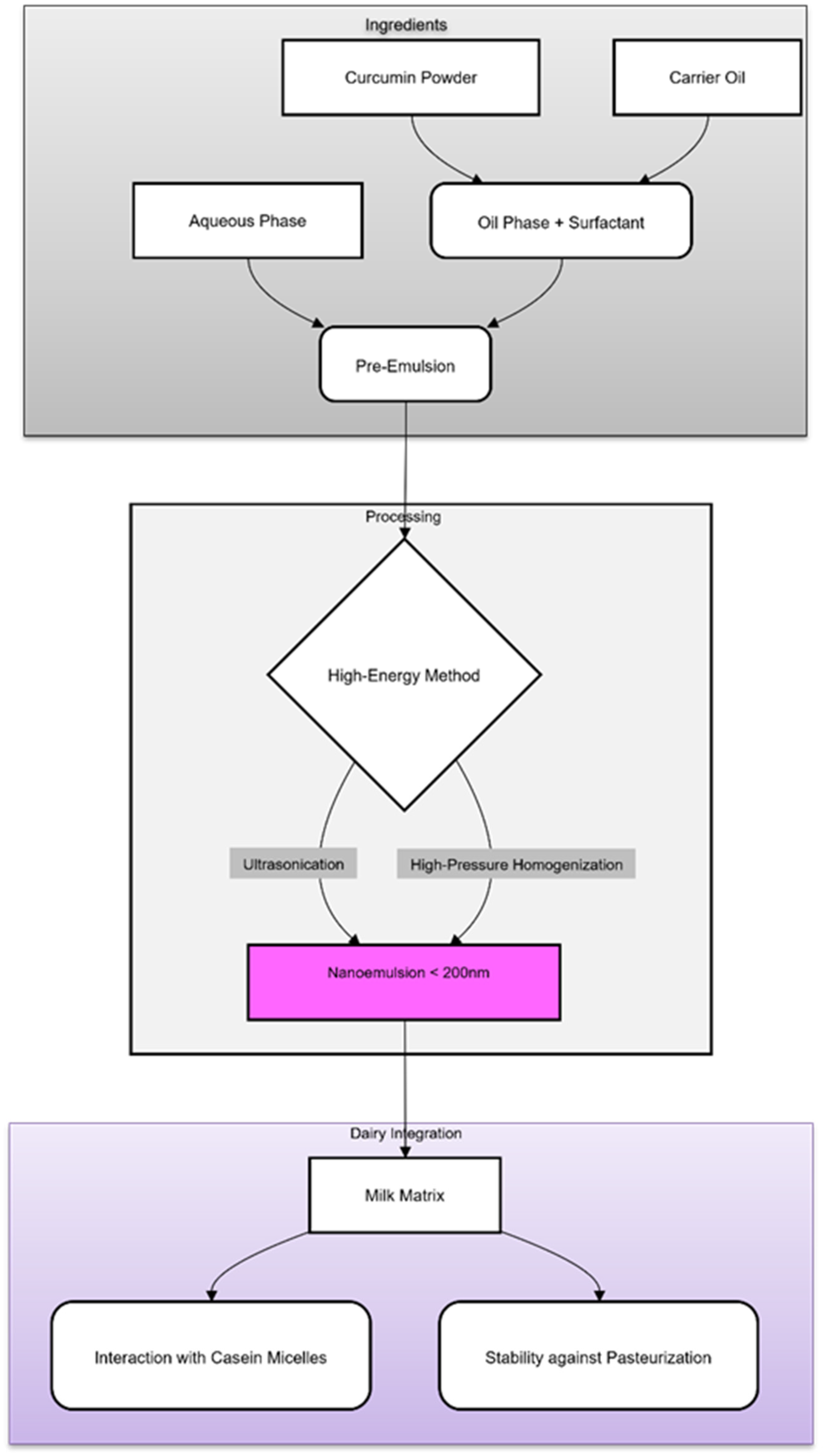

3. Nanoemulsion Systems: A Delivery Solution

3.1. Fundamentals of O/W Nanoemulsions

3.2. Formulation Components

3.3. Preparation Methods (High and Low Energy)

4. Characterization of Curcumin-Loaded Nanoemulsions

| Method | Principle of Droplet Disruption | Typical Particle Size | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Pressure Homogenization (HPH)/Micro-fluidization | Intense shear, turbulence, and cavitation from forcing emulsion through a narrow valve or micro-channels. | <150 nm, monodisperse | Highly scalable, industry standard (especially in dairy), reproducible, produces small/uniform droplets. | Higher financial and energy cost, can generate significant heat, potential for over-processing. | [60,61] |

| Ultrasonication | Acoustic cavitation: high-intensity sound waves create and collapse micro-bubbles, generating localized shear forces. | 50–200 nm | Convenient for lab-scale, high encapsulation efficiency. Can produce very small droplets. | Scalability is challenging. Potential for probe contamination, risk of over-processing. | [64,65] |

| Phase Inversion Temperature (PIT) | Change in surfactant solubility and curvature with temperature, leading to spontaneous self-assembly upon cooling. | 20–100 nm | Low energy, sophisticated (no mechanical stress), can produce extremely small droplets. | Requires non-ionic, temperature-sensitive surfactants; formulation is highly specific; sensitive to temperature control. | [66,67] |

| Spontaneous Emulsification (SE) | Spontaneous self-assembly as a water-miscible solvent (e.g., ethanol) containing oil and surfactant diffuses into the aqueous phase. | 100–300 nm | Simplest method, no energy input required. | Often produces larger, more polydisperse droplets; requires a (potentially undesirable) organic solvent; limited by surfactant/oil-specific thermodynamics. | [69,70] |

| Protein-Stabilized Nanoemulsification | Proteins such as whey protein form viscoelastic films at the oil–water interface, offering essential steric and electrostatic stabilization while enhancing bioaccessibility. | ~80–200 nm | Natural, food-grade; good steric and electrostatic stabilization; improved bioaccessibility. | Sensitive to pH, ionic strength, and heat. | [22,84] |

| Polysaccharide Stabilized Nanoemulsification | Polysaccharides (e.g., pectin, xanthan gum, alginate, Tremella polysaccharides) enhance continuous-phase viscosity while limiting droplet movement and coalescence through steric hindrance and electrostatic repulsion. | ~100–300 nm | Clean-label; food-grade; improves physical stability; inhibits droplet aggregation; enhances storage stability. | Weak interfacial activity alone; often requires combination with proteins or surfactants to form strong interfacial films. | [85,86] |

| Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Multilayer Assembly | Sequential deposition of oppositely charged proteins and polysaccharides around droplets forming multilayer interfacial films. | ~100–250 nm | Excellent stability across pH and ionic strength; controlled/sustained release. | Multistep process; higher formulation complexity. | [87,88] |

| Pickering Nanoemulsions (Biopolymer Particles) | Solid biopolymer particles form a steric barrier at the oil–water interface, effectively preventing coalescence and enhancing emulsion stability. | ~150–400 nm | Exceptional physical stability; reduced need for molecular surfactants. | Larger particle size required; limited food-grade particle options; many particles need surface modification. | [89,90] |

| Protein–Polysaccharide Complex Coacervation (Bulk Complexation) | Electrostatic complexation of oppositely charged proteins and polysaccharides forms a powerful protective layer at the interface. | 100–250 nm | Improved physical and oxidative stability; enhanced encapsulation efficiency; controlled release. | Highly pH- and ionic-strength dependent; formulation optimization required. | [91,92,93] |

5. Application for Dairy Beverages

5.1. The Dairy Matrix: A Complex Colloid

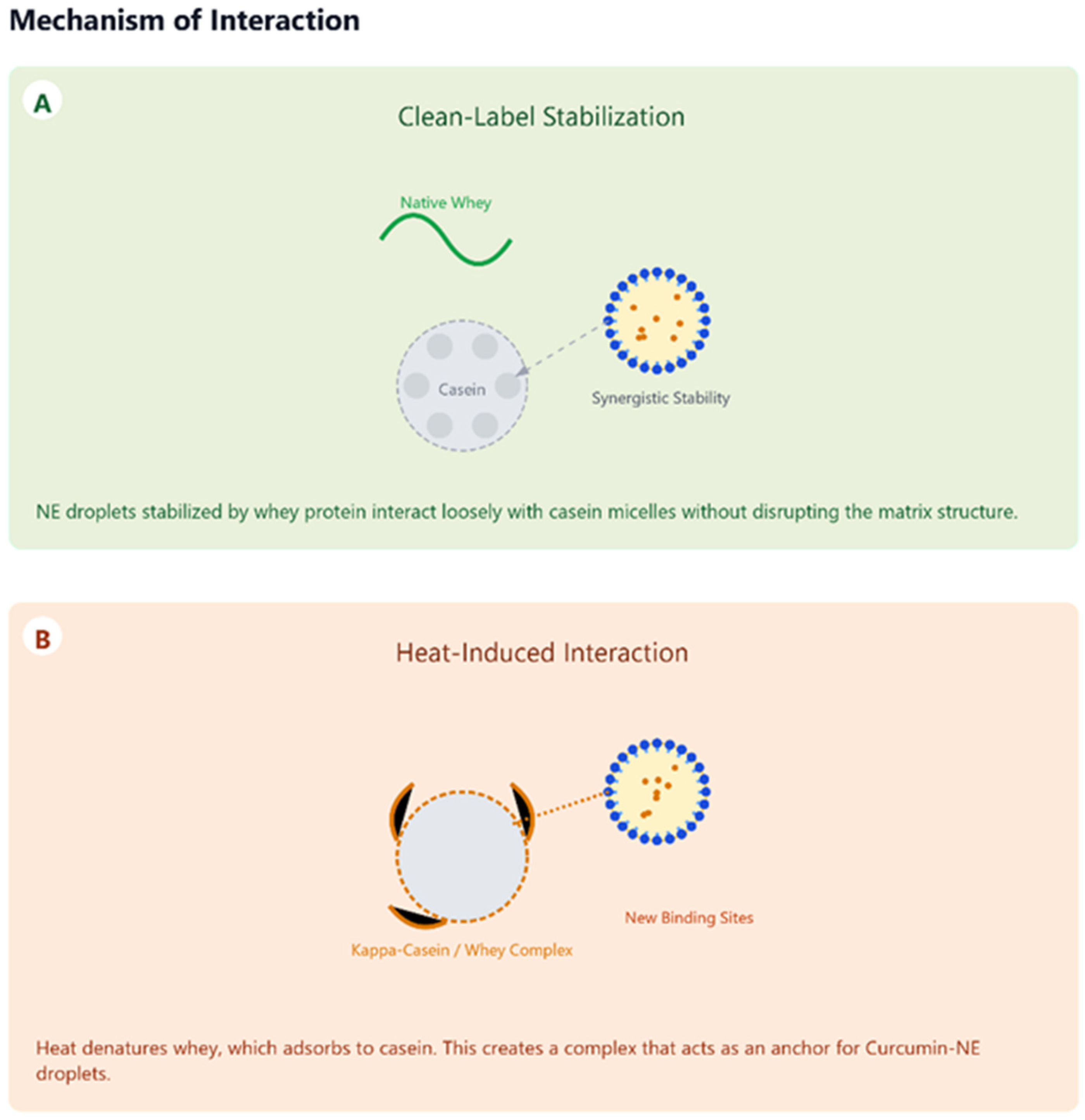

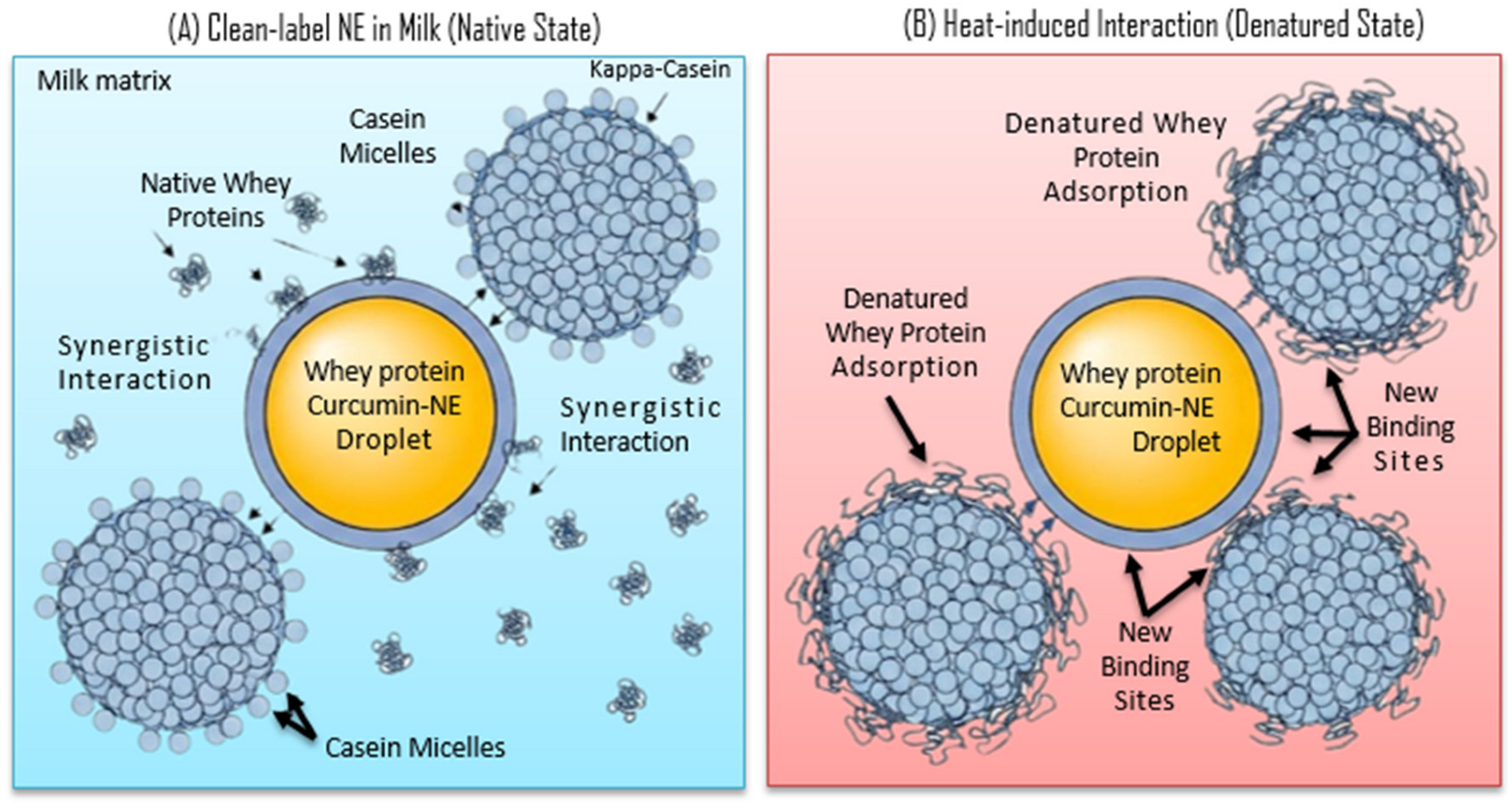

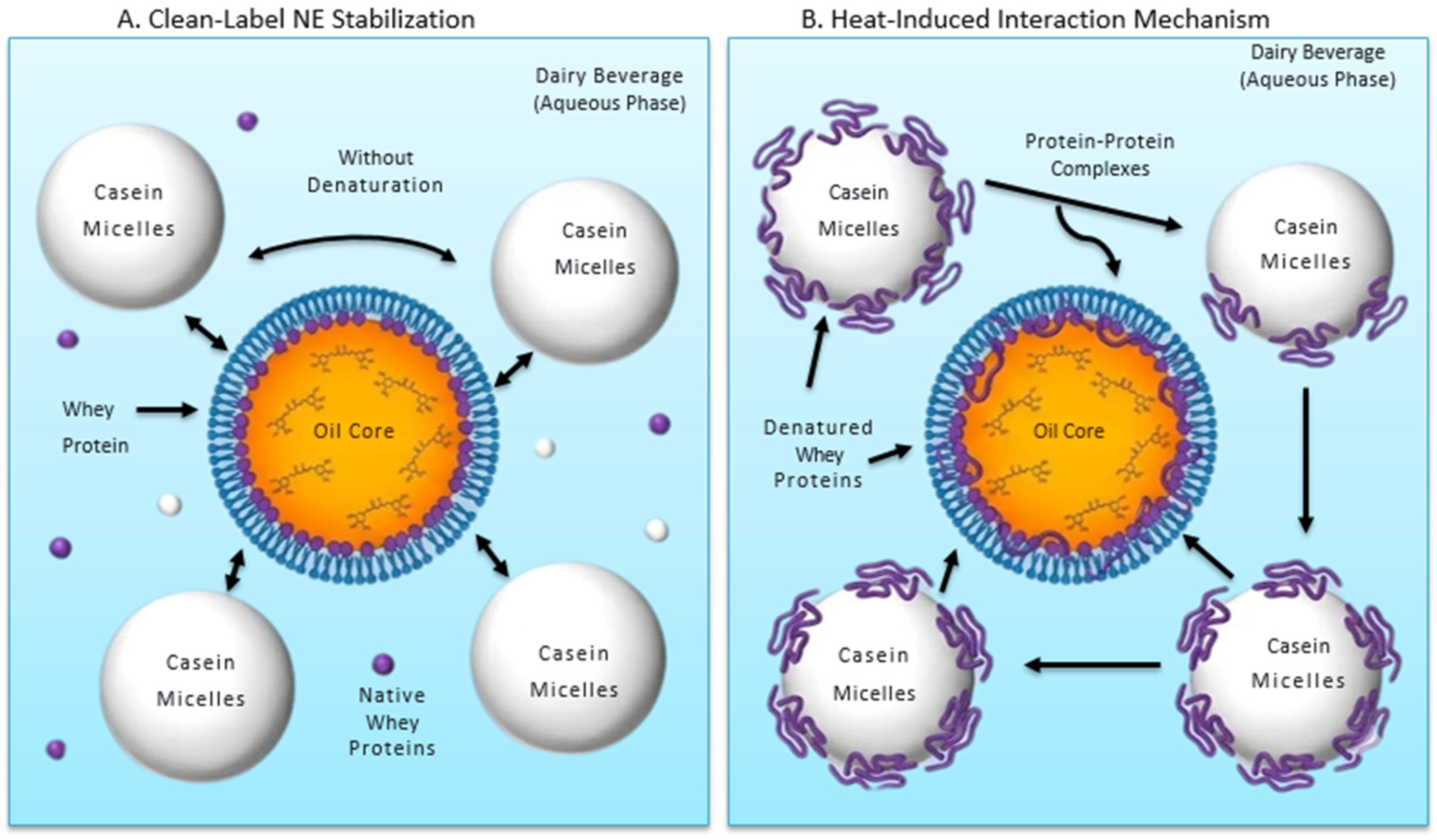

5.2. Interactions with Milk Components

6. Case Studies in Dairy Fortification

6.1. Fluid Milk

6.2. Fermented Beverages (Yogurt)

6.3. Cheese

7. Sensory Impact and Consumer Acceptance

8. Functional Performance: Stability and Bioavailability

8.1. Physicochemical Stability

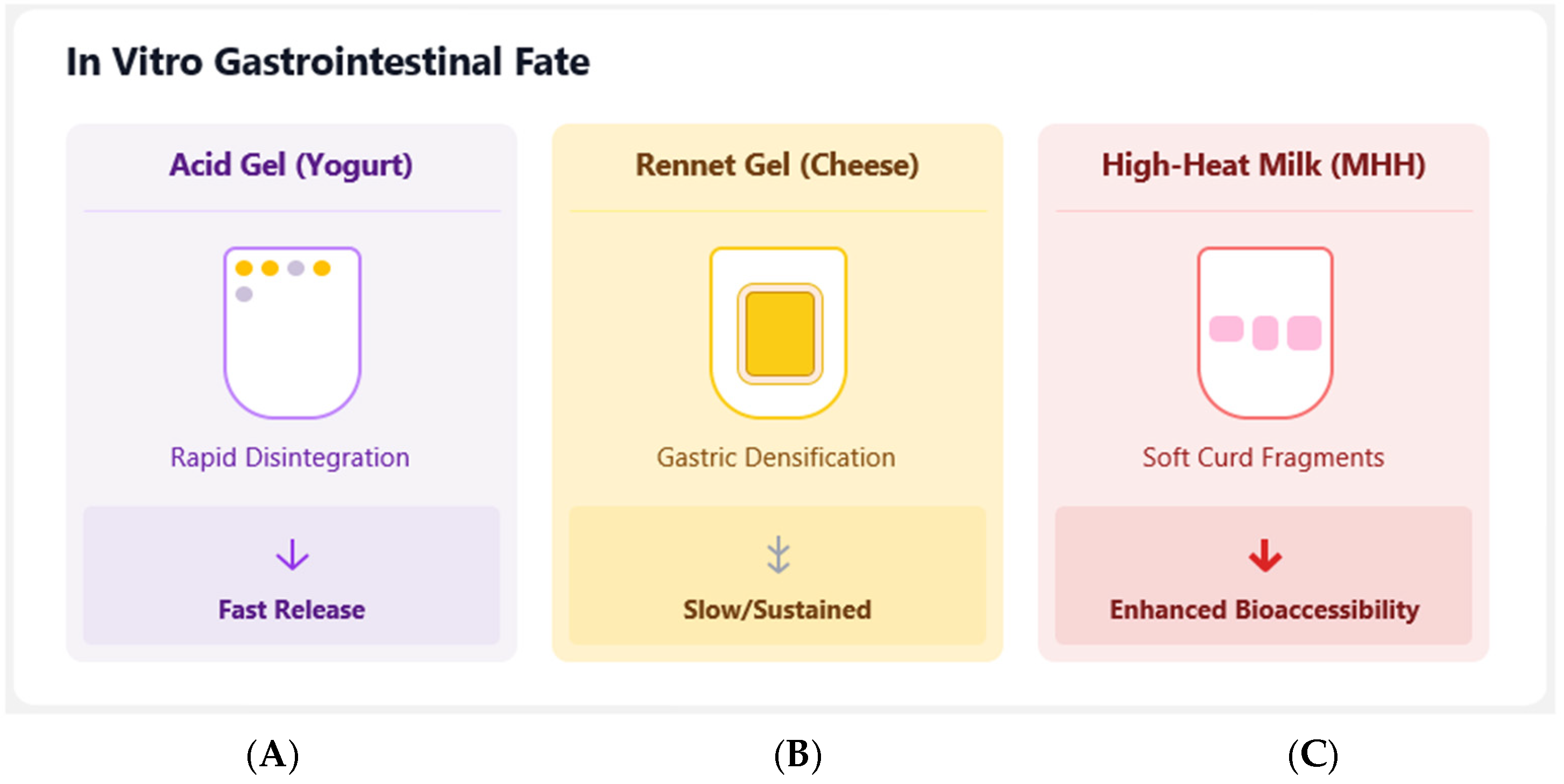

8.2. In Vitro Digestion and Bioaccessibility

8.3. In Vivo Bioavailability and Research Gaps

9. Technological Challenges and Future Perspectives

9.1. Industrial Scale-Up and Stability

9.2. Regulatory Landscape

10. Future Trends and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Islam, F.; Saeed, F.; Afzaal, M.; Hussain, M.; Ikram, A.; Khalid, M.A. Food grade nanoemulsions: Promising delivery systems for functional ingredients. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptan, B. Use of Nanoemulsion Technology in Dairy Industry. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 2415–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panghal, A.; Chhikara, N.; Anshid, V.; Sai Charan, M.V.; Surendran, V.; Malik, A.; Dhull, S.B. Nanoemulsions: A Promising Tool for Dairy Sector. In Nanobiotechnology Bioformulations; Prasad, R., Kumar, V., Kumar, M., Choudhary, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otchere, E.; McKay, B.M.; English, M.M.; Aryee, A.N.A. Current trends in nano-delivery systems for functional foods: A systematic review. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, U.K.; Shah, N.N.; Muley, A.B.; Singhal, R.S. Complexation of curcumin using proteins to enhance aqueous solubility and bioaccessibility: Pea protein vis-à-vis whey protein. J. Food Eng. 2021, 292, 110258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, H.; Islam, M.; Saeed, M.; Ahmad, H.; Al-Asmari, F.; Ramadan, M.F.; Alissa, M.; Arif, M.A.; Rana, M.U.J.; Subtain, M. On the health effects of curcumin and its derivatives. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 8623–8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saadony, M.T.; Yang, T.; Korma, S.A.; Sitohy, M.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A.; Selim, S.; Al Jaouni, S.K.; Salem, H.M.; Mahmmod, J.; Soliman, S.M.; et al. Impacts of turmeric and its principal bioactive curcumin on human health: Pharmaceutical, medicinal, and food applications: A comprehensive review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1040259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, M.; Girisa, S.; BharathwajChetty, B.; Vishwa, R.; Kunnumakkara, A.B. Curcumin Formulations for Better Bioavailability: What We Learned from Clinical Trials Thus Far? ACS Omega Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 8, 10713–10746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; McClements, D.J. Formulation of More Efficacious Curcumin Delivery Systems Using Colloid Science: Enhanced Solubility, Stability, and Bioavailability. Molecules 2020, 25, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus Cenobio-Galindo, A.; Campos-Montiel, R.G.; Jimenez-Alvarado, R.; Almaraz-Buendia, I.; Medina-Perez, G.; Fern, F. Development and incorporation of nanoemulsions in food. Int. J. Food Stud. 2019, 8, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slika, L.; Patra, D. A short review on chemical properties, stability and nano-technological advances for curcumin delivery. Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2020, 17, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.D.; Pannu, K.S.S. Turmeric Based Aqueous Dispersible Formulations. 2020. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2020240581A1/en (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Qazi, H.J.; Ye, A.; Acevedo-Fani, A.; Singh, H. Impact of Recombined Milk Systems on Gastrointestinal Fate of Curcumin Nanoemulsion. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 890876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi Yazdi, S.; Corredig, M. Heating of milk alters the binding of curcumin to casein micelles. A fluorescence spectroscopy study. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalraj, A.; Pius, A.; Gopi, S.; Gopi, S. Biological activities of curcuminoids, other biomolecules from turmeric and their derivatives—A review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2017, 7, 205–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiorcea-Paquim, A.-M. Electrochemical Sensing of Curcumin: A Review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuacharoen, T.; Sabliov, C.M. Comparative effects of curcumin when delivered in a nanoemulsion or nanoparticle form for food applications: Study on stability and lipid oxidation inhibition. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 113, 108319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, T.; Lin, F.; Chen, M.; Zhang, G.; Feng, Z. Research progress on the mechanism of curcumin anti-oxidative stress based on signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1548073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Sarkar, N. Exploring the World of Curcumin: Photophysics, Photochemistry, and Applications in Nanoscience and Biology. ChemBioChem 2024, 25, e202400335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, O.N.; Schneider, C. Vanillin and ferulic acid are not the major degradation products of curcumin. Trends Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.C.; Prasad, S.; Kim, J.H.; Patchva, S.; Webb, L.J.; Priyadarsini, I.K.; Aggarwal, B.B. Multitargeting by curcumin as revealed by molecular interaction studies. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 1937–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Parastouei, K.; Abbaszadeh, S. Development of curcumin-loaded nanoemulsion stabilized with texturized whey protein concentrate: Characterization, stability and in vitro digestibility. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 12, 1655–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, G. Emergent mechanistic diversity of enzyme-catalyzed β-diketone cleavage. Biochem. J. 2005, 388, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusydi, F.; Susanti, E.D.; Puspitasari, I.; Fadilla, R.N.; Madinah, R.; Mark-Lee, W.F. Probing Curcumin Reactive Conformers in Keto-enol Tautomerization Enhanced by Clustering with t-SNE. J. Mol. Model. 2026, 32, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Rayess, Y.E.; Rizk, A.A.; Sadaka, C.; Zgheib, R.; Zam, W.; Sestito, S.; Rapposelli, S.; Neffe-Skocińska, K.; Zielińska, D. Turmeric and its major compound curcumin on health: Bioactive effects and safety profiles for food, pharmaceutical, biotechnological and medicinal applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 550909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, Y.; Alam, W.; Ullah, H.; Dacrema, M.; Daglia, M.; Khan, H.; Arciola, C.R. Antimicrobial potential of curcumin: Therapeutic potential and challenges to clinical applications. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altobelli, E.; Angeletti, P.M.; Marziliano, C.; Mastrodomenico, M.; Giuliani, A.R.; Petrocelli, R. Potential Therapeutic Effects of Curcumin on Glycemic and Lipid Profile in Uncomplicated Type 2 Diabetes—A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, D.A.M.; Salamt, N.; Yusuf, A.N.M.; Kashim, M.I.A.M.; Mokhtar, M.H. Potential Health Benefits of Curcumin on Female Reproductive Disorders: A Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.F.; Guo, Q.H.; Wei, X.Y.; Chen, S.Y.; Deng, S.; Liu, J.J.; Yin, N.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, W.J. Cardioprotective effect of curcumin on myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: A meta-analysis of preclinical animal studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1184292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalchevski, D.A.; Kolev, S.K.; Zaharieva, L.; Trifonov, D.; Milenov, T.; Antonov, L. Curcumin tautomers stabilization in water and in methanol–comparing the effect of explicit solvation by using ab initio dynamical simulations. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 437, 128526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidi, S.; Rafiee, Z.; Kakanejadifard, A. Design and synthesis of curcumin nanostructures: Evaluation of solubility, stability, antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 116, 105308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, T.; Sen, K. Liposomal Encapsulation of Different Anticancer Drugs: An Effective Drug Delivery Technique. BioNanoScience 2024, 14, 3476–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooda, A.; Mann, B.; Sharma, R.; Tripathi, A.D.; Agarwal, A. Effect of pH variation on physicochemical and morphological properties of Micellar Casein Concentrate and its utilization for nanoencapsulation of curcumin. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2025, 78, e13162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Yang, H.; Lu, F.; Zhu, M. Quinoa Protein/Sodium Alginate Complex-Stabilized Pickering Emulsion for Sustained Release of Curcumin and Enhanced Anticancer Activity Against HeLa Cells. Foods 2025, 14, 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buniowska-Olejnik, M.; Mykhalevych, A.; Urbański, J.; Berthold-Pluta, A.; Michałowska, D.; Banach, M. The potential of using curcumin in dairy and milk-based products—A review. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 5245–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabanelli, R.; Brogi, S.; Calderone, V. Improving Curcumin Bioavailability: Current Strategies and Future Perspectives. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Albuquerque Mendes, M.K.; dos Santos Oliveira, C.B.; da Silva Medeiros, C.M.; dos Santos, L.R.; Lopes Júnior, C.A.; Vieira, E.C. Challenges and Strategies for Bioavailability of Curcumin. In Curcumin and Neurodegenerative Diseases; Rai, M., Feitosa, C.M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoncini-Silva, C.; Vlad, A.; Ricciarelli, R.; Giacomo Fassini, P.; Suen, V.M.M.; Zingg, J.-M. Enhancing the Bioavailability and Bioactivity of Curcumin for Disease Prevention and Treatment. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, P.; Gao, C.; Tao, J.; Ge, Z.; Zhu, D.; Bi, Y. Modulation of gut microbiota contributes to curcumin-mediated attenuation of hepatic steatosis in rats. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 1801–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Inbaraj, B.S.; Dikkala, P.K.; Sridhar, K.; Mude, A.N.; Narsaiah, K. Preparation of Curcumin Hydrogel Beads for the Development of Functional Kulfi: A Tailoring Delivery System. Foods 2022, 11, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.J.; McClements, D.J. Nanoemulsions as delivery systems for lipophilic nutraceuticals: Strategies for improving their formulation, stability, functionality and bioavailability. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Panigrahi, C.; Agarwal, S.; Khuntia, A.; Sahoo, M. Recent trends and advancements in nanoemulsions: Production methods, functional properties, applications in food sector, safety and toxicological effects. Food Phys. 2024, 1, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, H.; Chen, H.; Lin, J.; Wang, Q. Food-Grade Nanoemulsions: Preparation, Stability and Application in Encapsulation of Bioactive Compounds. Molecules 2019, 24, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.F.S.; Martins, J.T.; Abrunhosa, L.; Vicente, A.A.; Pinheiro, A.C. Nanoemulsions for Enhancement of Curcumin Bioavailability and Their Safety Evaluation: Effect of Emulsifier Type. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurpreet, K.; Singh, S. Review of nanoemulsion formulation and characterization techniques. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 80, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sun, P.; Duan, C.; Cao, Y.; Kong, B.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q. Improving stability and bioavailability of curcumin by quaternized chitosan coated nanoemulsion. Food Res. Int. 2023, 174, 113634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iskandar, B.; Liu, T.-W.; Mei, H.-C.; Kuo, I.-C.; Surboyo, M.D.C.; Lin, H.M.; Lee, C.K. Herbal nanoemulsions in cosmetic science: A comprehensive review of design, preparation, formulation, and characterization. J. Food Drug Anal. 2024, 32, 428–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azami, S.J.; Teimouri, A.; Keshavarz, H.; Amani, A.; Esmaeili, F.; Hasanpour, H.; Elikaee, S.; Salehiniya, H.; Shojaee, S. Curcumin nanoemulsion as a novel chemical for the treatment of acute and chronic toxoplasmosis in mice. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 7363–7374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đoković, J.B.; Savić, S.M.; Mitrović, J.R.; Nikolic, I.; Marković, B.D.; Randjelović, D.V.; Antic-Stankovic, J.; Božić, D.; Cekić, N.D.; Stevanović, V.; et al. Curcumin Loaded PEGylated Nanoemulsions Designed for Maintained Antioxidant Effects and Improved Bioavailability: A Pilot Study on Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, A.; Hernández-Becerra, J.; Cavazos-Garduño, A.; Vernon-Carter, E.; García, H. Preparation and characterization of curcumin nanoemulsions obtained by thin-film hydration emulsification and ultrasonication methods. Rev. Mex. Ing. Quím. 2016, 15, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.-H.; Yan, H.H.; Chen, Z.-Q.; He, M. Effects of emulsifier type and environmental stress on the stability of curcumin emulsion. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2017, 38, 1375–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Xiao, H.; McClements, D.J. Designing excipient emulsions to increase nutraceutical bioavailability: Emulsifier type influences curcumin stability and bioaccessibility by altering gastrointestinal fate. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 2475–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Zeng, Q.; Tai, K.; He, X.; Yao, Y.; Hong, X.; Yuan, F. Development of stable curcumin nanoemulsions: Effects of emulsifier type and surfactant-to-oil ratios. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3485–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, T.; Ahmed, A. Tween 80 and Soya-Lecithin-Based Food-Grade Nanoemulsions for the Effective Delivery of Vitamin D. Langmuir 2020, 36, 2886–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiner, T.B.; Santamaria-Echart, A.; Peres, A.M.; Dias, M.M.; Pinho, S.P.; Barreiro, M.F. Study of binary mixtures of Tribulus terrestris extract and Quillaja bark saponin as oil-in-water nanoemulsion emulsifiers. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2024, 27, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammak, I.; do Amaral Sobral, P.J. Curcumin nanoemulsions stabilized with natural plant-based emulsifiers. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, K.; Matamala, C.; Martínez, N.; Zúñiga, R.N.; Troncoso, E. Comparative Study of Physicochemical Properties of Nanoemulsions Fabricated with Natural and Synthetic Surfactants. Processes 2021, 9, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ma, Y.; Cui, J. Whey-protein-stabilized nanoemulsions as a potential delivery system for water-insoluble curcumin. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 59, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, S.; Dash, P.; Panda, P.K.; Yang, P.-C.; Srivastav, P.P. Interaction of dairy and plant proteins for improving the emulsifying and gelation properties in food matrices: A review. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 3199–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-T.; Wu, H.-T.; Chang, I.-C.; Chen, H.-W.; Fang, W.-P. Preparation of curcumin-loaded liposome with high bioavailability by a novel method of high-pressure processing. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2022, 244, 105191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusril, N.A.; Abu Bakar, S.I.; Khalil, K.A.; Md Saad, W.M.; Wen, N.K.; Adenan, M.I. Development and Optimization of Nanoemulsion from Ethanolic Extract of Centella asiatica (NanoSECA) Using D-Optimal Mixture Design to Improve Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 3483511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Mackie, A.; Zhang, M.; Dai, L.; Liu, J.; Mao, L.; Yuan, F.; Gao, Y. Co-encapsulation of curcumin and β-carotene in Pickering emulsions stabilized by complex nanoparticles: Effects of microfluidization and thermal treatment. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 122, 107064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei Chen, H.; Po Fang, W. A novel method for the microencapsulation of curcumin by high-pressure processing for enhancing the stability and preservation. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 613, 121403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algahtani, M.S.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Nourein, I.H.; Albarqi, H.A.; Alyami, H.S.; Alyami, M.H.; Alqahtani, A.A.; Alasiri, A.; Algahtani, T.S.; Mohammed, A.A.; et al. Preparation and Characterization of Curcumin Nanoemulgel Utilizing Ultrasonication Technique for Wound Healing: In Vitro, Ex Vivo, and In Vivo Evaluation. Gels 2021, 7, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Páez-Hernández, G.; Mondragón-Cortez, P.; Espinosa-Andrews, H. Developing curcumin nanoemulsions by high-intensity methods: Impact of ultrasonication and microfluidization parameters. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 111, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaiko, J.S.; McClements, D.J. Formation of Food-Grade Nanoemulsions Using Low-Energy Preparation Methods: A Review of Available Methods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, Q.-H.; Le Thi, T.-T.; Nguyen, T.-C.; Tran, T.-V.; Le, Q.-T.; Luu, T.-T.; Dinh, V.-P. Facile synthesis of novel nanocurcuminoids–sacha inchi oil using the phase inversion temperature method: Characterization and antioxidant activity. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.-H.; Thanh-Ho Thuy, T.; Thanh-Tu Nguyen, T. Fabrication of a narrow size nano curcuminoid emulsion by combining phase inversion temperature and ultrasonication: Preparation and bioactivity. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 9658–9667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booravilli, J.; Sirisolla, J.D. Spontaneous Emulsification as a Novel Approach for the Preparation and Characterization of Curcumin Nanoemulsion: Advancing Bioavailability and Therapeutic Efficacy. J. Young-Pharm. 2025, 17, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaset, M.A.; Nasr, M.; Ibrahim, B.M.M.; Ahmed-Farid, O.A.H.; Bakeer, R.M.; Hassan, N.S.; Ahmed, R.F. Curcumin nanoemulsion counteracts hepatic and cardiac complications associated with high-fat/high-fructose diet in rats. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, H.J.; Choi, M.-J.; Kim, J.T.; Park, S.H.; Park, H.J.; Shin, G.H. Development of food-grade curcumin nanoemulsion and its potential application to food beverage system: Antioxidant property and in vitro digestion. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, N745–N753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharat, M.; Du, Z.; Zhang, G.; McClements, D.J. Physical and chemical stability of curcumin in aqueous solutions and emulsions: Impact of pH, temperature, and molecular environment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuca, M.D.; Racovita, R.C. Curcumin: Overview of Extraction Methods, Health Benefits, and Encapsulation and Delivery Using Microemulsions and Nanoemulsions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urošević, M.; Nikolić, L.; Gajić, I.; Nikolić, V.; Dinić, A.; Miljković, V. Curcumin: Biological activities and modern pharmaceutical forms. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdouss, H.; Pourmadadi, M.; Zahedi, P.; Abdouss, M.; Yazdian, F.; Rahdar, A.; Díez-Pascual, A.M. Green synthesis of chitosan/polyacrylic acid/graphitic carbon nitride nanocarrier as a potential pH-sensitive system for curcumin delivery to MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 125134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirpara, D.; Chavda, V.; Hirapara, N.; Kumar, S. Inorganic salt-induced micellar morphologies in deep eutectic solvent: Structure and curcumin solubilization. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 411, 125761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshan, Z.; Haddadi-Asl, V.; Ahmadi, H.; Moussaei, M. Curcumin-Encapsulated Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) Nanoparticles: A Comparison of Drug Release Kinetics from Particles Prepared via Electrospray and Nanoprecipitation. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2024, 309, 2400040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento Valencia, M.; da Silva Júnior, M.F.; Xavier-Júnior, F.H.; de Oliveira Veras, B.; Barbosa Sales de Albuquerque, P.; de Oliveira Borba, E.F.; Gonçalves da Silva, T.; Lansky Xavier, V.; de Souza, M.P.; das Graças Carneiro-da-Cunha, M. Characterization of curcumin-loaded lecithin-chitosan bioactive nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Qi, B.; Li, Y. Oxidized dextran improves the stability and effectively controls the release of curcumin loaded in soybean protein nanocomplexes. Food Chem. 2024, 431, 137089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, T.P.; Mann, B.; Kumar, R.; Singh, R.R.B.; Sharma, R.; Bhardwaj, M.; Athira, S. Preparation and characterization of nanoemulsion encapsulating curcumin. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 43, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.A.; Awasthi, R.; Pandey, R.P.; Kar, S.K. Curcumin-loaded nanoemulsion for acute lung injury treatment via nebulization: Formulation, optimization and in vivo studies. ADMET DMPK 2025, 13, 2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, D.; López, O.; Sanhueza, C.; Chávez-Aravena, C.; Villagra, J.; Bustamante, M.; Acevedo, F. Co-Encapsulation of Curcumin and α-Tocopherol in Bicosome Systems: Physicochemical Properties and Biological Activity. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wei, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Q.; Huang, Q.; Xue, C. Fabrication and characterization of core-shell gliadin/tremella polysaccharide nanoparticles for curcumin delivery: Encapsulation efficiency, physicochemical stability and bioaccessibility. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, N.; Suman, S.; Rai, D.C.; Meena, S.; Duary, R.K.; Meena, K.K.; Mishra, S. Curcumin encapsulation via protein-stabilized emulsions: Comparative formulation and characterization using whey, soy, and pea proteins. Sustain. Food Technol. 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; He, W.; Huang, X.; Yin, J.; Nie, S. The emulsification and stabilization mechanism of an oil-in-water emulsion constructed from tremella polysaccharide and Citrus pectin. Foods 2024, 13, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, T.; Ma, X.; Hu, H.; Xiang, F.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Dong, H.; Adhikari, B.; Wang, Q.; Shi, A. Advances in emulsion stability: A review on mechanisms, role of emulsifiers, and applications in food. Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Shao, G.; Jin, Y.; Yang, N.; Xu, X. Applying layer-by-layer deposition to enhance stability and rheological behavior of emulsions: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 158, 110537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhong, M.; Rashid, A.; Qayum, A.; Liang, Q.; Rehman, A.; Ma, H.; Ren, X. Interfacial multilayer self-assembly of protein and polysaccharides: Ultrasonic regulation, stability and application in delivery lutein. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 272, 132880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassani, L.V.; Gomez Zavaglia, A. Pickering emulsions in food and nutraceutical technology: From delivering hydrophobic compounds to cutting-edge food applications. Explor. Foods Foodomics 2024, 2, 408–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Fan, L.; Li, J.; Zhong, S. Pickering emulsions stabilized by biopolymer-based nanoparticles or hybrid particles for the development of food packaging films: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 146, 109185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrosan, M.; Al-Rabadi, N.; Alu’datt, M.H.; Al-Qaisi, A.; Al-Shunnaq, E.E.; Abu-Khalaf, N.; Maghaydah, S.; Assaf, T.; Hidmi, T.; Tan, T.-C.; et al. Complex Coacervation of Plant-Based Proteins and Polysaccharides: Sustainable Encapsulation Techniques for Bioactive Compounds. Food Eng. Rev. 2025, 17, 1059–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliyaei, N.; Tanideh, N.; Moosavi-Nasab, M. Fucoidan–ovalbumin protein-based complex coacervates: Preparation, characterization, and encapsulation of fucoxanthin. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025. Available online: https://scijournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jsfa.70379 (accessed on 1 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Wei, Z.; Xue, C. Recent advances in nutraceutical delivery systems constructed by protein–polysaccharide complexes: A systematic review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, U.; Gill, H.; Chandrapala, J. Casein Micelles as an Emerging Delivery System for Bioactive Food Components. Foods 2021, 10, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Qin, J.; Ji, W.; Palupi, N.W.; Yang, M. Interaction between curcumin and ultrafiltered casein micelles or whey protein, and characteristics of their complexes. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 1582–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đoković, J.B.; Demisli, S.; Savić, S.M.; Marković, B.D.; Cekić, N.D.; Randjelovic, D.V.; Mitrović, J.R.; Lunter, D.J.; Papadimitriou, V.; Xenakis, A.; et al. The Impact of the Oil Phase Selection on Physicochemical Properties, Long-Term Stability, In Vitro Performance and Injectability of Curcumin-Loaded PEGylated Nanoemulsions. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalakshmi, L.; Choudhary, P.; Moses, J.A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Emulsion electrospraying and spray drying of whey protein nano and microparticles with curcumin. Food Hydrocoll. Health 2023, 3, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibzahedi, S.M.T.; Altintas, Z. Transglutaminase-Induced Free-Fat Yogurt Gels Supplemented with Tarragon Essential Oil-Loaded Nanoemulsions: Development, Optimization, Characterization, Bioactivity, and Storability. Gels 2022, 8, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagale, U.; Kadi, A.; Abotaleb, M.; Potoroko, I.; Sonawane, S.H. Prospect of Bioactive Curcumin Nanoemulsion as Effective Agency to Improve Milk Based Soft Cheese by Using Ultrasound Encapsulation Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardiñas-Valdés, M.; García-Galindo, H.S.; Chay-Canul, A.J.; Velázquez-Martínez, J.R.; Hernández-Becerra, J.A.; Ochoa-Flores, A.A. Ripening Changes of the Chemical Composition, Proteolysis, and Lipolysis of a Hair Sheep Milk Mexican Manchego-Style Cheese: Effect of Nano-Emulsified Curcumin. Foods 2021, 10, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosme, F.; Rocha, T.; Marques, C.; Barroso, J.; Vilela, A. Innovative Approaches in Sensory Food Science: From Digital Tools to Virtual Reality. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Li, Y.; McClements, D.J.; Xiao, H. Nanoemulsion- and emulsion-based delivery systems for curcumin: Encapsulation and release properties. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, D.; Chen, X.; Liang, C.; Yuan, M.; Guo, Y.; Li, J.; Shen, H.; Wu, D. The resistance of BSA-Dex conjugate nanoemulsions to depletion flocculation induced by excessive dextran in Maillard reaction. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 413, 126056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Ahmadi, S.H.; Babak, P.; Bryant, S.L.; Kantzas, A. On the Stability of Pickering and Classical Nanoemulsions: Theory and Experiments. Langmuir 2023, 39, 6975–6991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siti Norazilah, M.; Norliza, J.; Suryani, S.; Sariah, S.; Jahurul, M.H.A.; Siti Norliyana, A.R.; Norziana, J. Techniques for nanoemulsion in milk and its application: A review. Int. Food Res. J. 2025, 32, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Kwon, S.; Gu, Z.; Selomulya, C. Stable nanoemulsions for poorly soluble curcumin: From production to digestion response in vitro. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 394, 123720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Fang, Q.; Li, P.; Zhang, C.; Yuan, Y.; Zhuang, H. Effects of Emulsifier Type and Post-Treatment on Stability, Curcumin Protection, and Sterilization Ability of Nanoemulsions. Foods 2021, 10, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.; Gonçalves, R.F.S.; Madalena, D.A.; Abrunhosa, L.; Vicente, A.A.; Pinheiro, A.C. Co-encapsulation of vitamin D 3 and curcumin in plant protein-based nanoemulsions: Formulation optimization, characterization, and in vitro digestion. Sustain. Food Technol. 2025, 3, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Carrasco, P.; Alemán, A.; González, E.; Gómez-Guillén, M.C.; Robert, P.; Giménez, B. Bioaccessibility, Intestinal Absorption and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Curcuminoids Incorporated in Avocado, Sunflower, and Linseed Beeswax Oleogels. Foods 2024, 13, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Xiao, H.; McClements, D.J. Utilizing Food Matrix Effects To Enhance Nutraceutical Bioavailability: Increase of Curcumin Bioaccessibility Using Excipient Emulsions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 2052–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, H.J.; Ye, A.; Acevedo-Fani, A.; Singh, H. In vitro digestion of curcumin-nanoemulsion-enriched dairy protein matrices: Impact of the type of gel structure on the bioaccessibility of curcumin. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 117, 106692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebi, K.; Shahsavani, F.; Mehravar, F.; Hatam, G.; Alimi, R.; Radfar, A.; Bahreini, M.S.; Pouryousef, A.; Teimouri, A. In vitro and in vivo anti-parasitic activity of curcumin nanoemulsion on Leishmania major (MRHO/IR/75/ER). BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, N.A.; Bruss, M.S.; Gardner, M.; Willis, W.L.; Mo, X.; Valiente, G.R.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jarjour, W.N.; Wu, L.-C. Oral Administration of Nano-Emulsion Curcumin in Mice Suppresses Inflammatory-Induced NFκB Signaling and Macrophage Migration. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, G.K.; Parhi, R.; Sahoo, S.K. Nanoemulsions in Food Industry. In Application of Nanotechnology in Food Science, Processing and Packaging; Egbuna, C., Jeevanandam, J.C., Patrick-Iwuanyanwu, K.N., Onyeike, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvall, M.N.; Knight, K. FDA Regulation of Nanotechnology; Beveridge and Diamond P.C.: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- More, S.; Bampidis, V.; Benford, D.; Bragard, C.; Halldorsson, T.; Hernández-Jerez, A.; Hougaard Bennekou, S.; Koutsoumanis, K.; Lambré, C.; Machera, K.; et al. Guidance on risk assessment of nanomaterials to be applied in the food and feed chain: Human and animal health. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Yadav, K.K.; Jha, M. Environmental, legal, regulatory, health, and safety issues of nanoemulsions. Ind. Appl. Nanoemuls. Micro Nano Technol. 2024, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Examples | Key Functions | Advantages | Clean-Label Restrictions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic small-molecule surfactants | Tween 20, Tween 80 | Reduce interfacial tension; form small, uniform droplets | Very high efficiency; excellent droplet size control; strong kinetic stability | Perceived as less “natural”; possible clean-label restrictions |

| Natural small-molecule surfactants | Lecithin (soy, egg), Quillaja saponin | Interfacial adsorption and stabilization | Natural origin; good emulsification; clean-label compliant | May form larger droplets; sometimes require co-emulsifiers |

| Biopolymers (proteins) | Whey protein isolate (WPI), caseins, sodium caseinate | Create thick viscoelastic interfacial layers, providing steric stabilization | Highly compatible with dairy matrices; strong long-term stability; clean-label | Heat sensitivity; possible pH- or ion-dependent interactions |

| Biopolymers (polysaccharides) | Gum Arabic, pectin, modified starch | Increase viscosity; contribute to steric/electrostatic stabilization | Natural, label-friendly; support long-term stability | Often require pairing with proteins or surfactants |

| Hybrid systems | Protein–polysaccharide complexes; lecithin + Tween blends | Combine multiple stabilization mechanisms | Tailored functionality; improved robustness during processing | More complex formulations; potential cost increases |

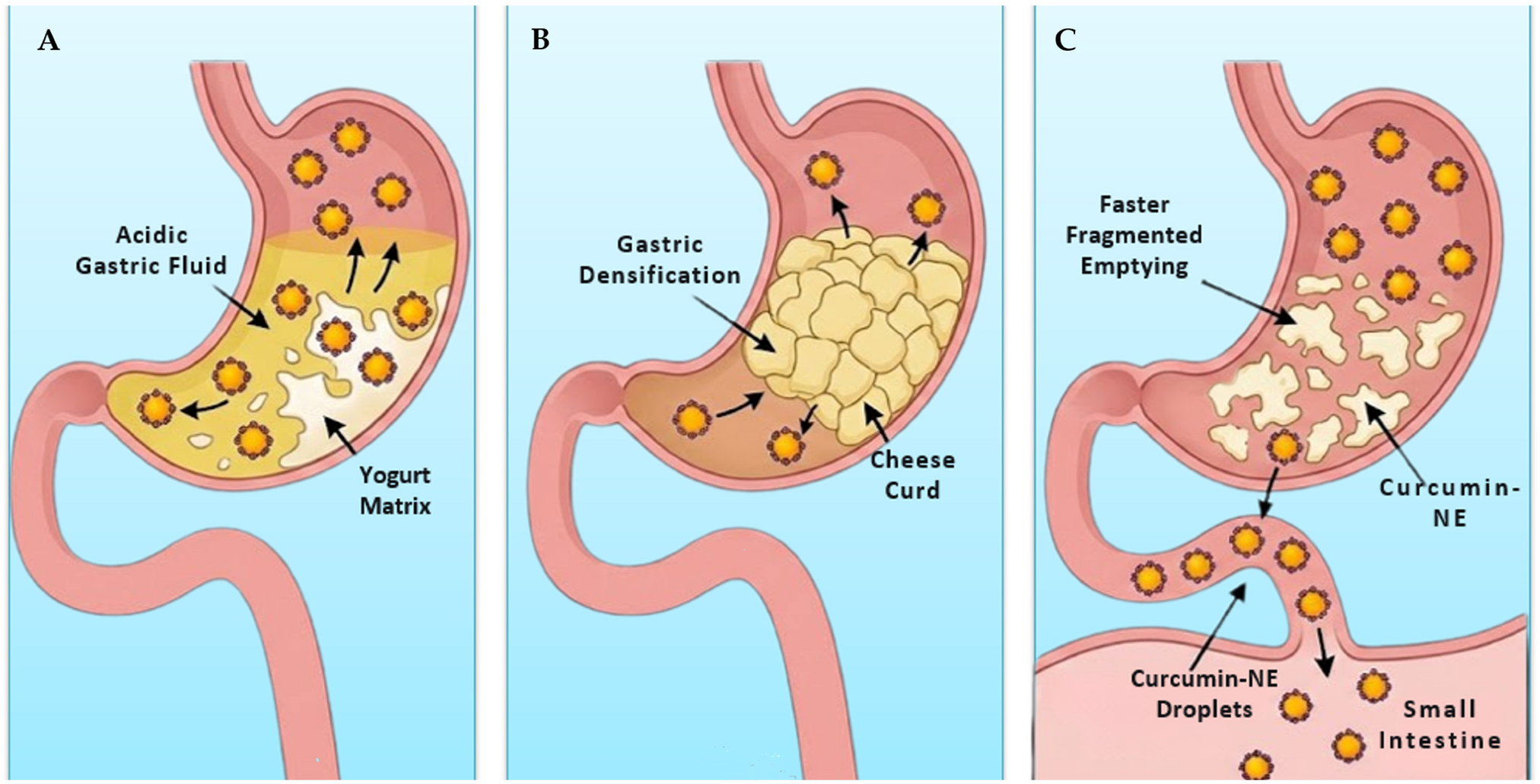

| Dairy Matrix | Processing/Storage Stability | Key In Vitro Bioaccessibility Finding | Controlling Mechanism/Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluid Milk (Reconstituted from High-Heat SMP) | _____ | Higher bioaccessibility than low- or medium-heat SMP milk. | Matrix structure: High-heat processing creates casein/whey complexes, leading to a soft, fragmented curd in the stomach. |

| Fluid Milk (Reconstituted from Low-Heat SMP) | _____ | Lower bioaccessibility than high-heat SMP milk. | Matrix structure: Forms a denser curd, slowing gastric emptying of the nanoemulsion. |

| Yogurt-Like (Acid Gel) | _____ | High (85–91%), with fast-release kinetics. | Matrix structure: Rapid protein disintegration in the stomach leads to fast gastric emptying. |

| Cheese-like (Rennet Gel) | _____ | High (85–91%), with slow, sustained release kinetics. | Matrix structure: Gel restructures and densifies in the stomach, physically entrapping the NE and slowing its release. |

| Fluid Milk (WPC-Stabilized NE) | Stable for pasteurization (63 °C/30 min) and sterilization (95 °C/10 min). Stable pH 3–7 and ionic strength (0.1–1 M NaCl). Stable 30 days @ 4 °C. | _____ | Stabilizer choice: Texturized WPC provides robust steric stabilization against processing stresses. |

| Soft Cheese (CUNE) | Improved shelf-life; better antioxidant and antimicrobial properties than control. | _____ | Dual function: NE acts as a natural preservative, improving sensory scores by preventing spoilage. |

| Milk (cream emulsion) | Micro-fluidization created uniform nano droplets in cream. | Bioaccessibility increased by ~30% after in vitro digestion. | Microfluidization effectively distributes curcumin in milk’s fat–protein interfaces, boosting antioxidant activity (DPPH, FRAP) and increasing interfacial area for efficient lipid digestion and curcumin bioaccessibility. |

| Refrigerated Kareish cheese | Stable at 40 °C for 4 weeks with consistent droplet size. | Increased antioxidant activity (42.31% vs. 19.23% control) and stronger antibacterial efficacy (lower MIC vs. S. aureus and B. cereus). | Integrated CRNE into cheese matrix without affecting protein/fat/pH, improving antioxidant and antimicrobial properties while maintaining the dairy matrix stability. |

| Stirred yogurt | No significant change in pH, acidity, or visual syneresis. | Maintained yogurt rheological and gel stability; no adverse texture. | SLNs are entrapped in the acid coagulated casein gel network without disrupting its structure, preserving yogurt stability. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pino, R.; Sicari, V.; Hussain, M.; Boakye, S.K.K.; Kanwal, F.; Yaseen, R.; Azhar, M.; Ahmad, Z.; Degraft-Johnson, B.; Kebede, A.A.; et al. Development of Curcumin-Loaded Nanoemulsions for Fortification and Stabilization of Dairy Beverages. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 885. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020885

Pino R, Sicari V, Hussain M, Boakye SKK, Kanwal F, Yaseen R, Azhar M, Ahmad Z, Degraft-Johnson B, Kebede AA, et al. Development of Curcumin-Loaded Nanoemulsions for Fortification and Stabilization of Dairy Beverages. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):885. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020885

Chicago/Turabian StylePino, Roberta, Vincenzo Sicari, Mudassar Hussain, Stockwin Kwame Kyei Boakye, Faiza Kanwal, Ramsha Yaseen, Manahel Azhar, Zeeshan Ahmad, Benic Degraft-Johnson, Amanuel Abebe Kebede, and et al. 2026. "Development of Curcumin-Loaded Nanoemulsions for Fortification and Stabilization of Dairy Beverages" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 885. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020885

APA StylePino, R., Sicari, V., Hussain, M., Boakye, S. K. K., Kanwal, F., Yaseen, R., Azhar, M., Ahmad, Z., Degraft-Johnson, B., Kebede, A. A., Tundis, R., & Loizzo, M. R. (2026). Development of Curcumin-Loaded Nanoemulsions for Fortification and Stabilization of Dairy Beverages. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 885. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020885