How Different Lipid Blends Affect the Quality and Sensory Attributes of Short Dough Biscuits

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Samples

2.3. Lipid Extraction

2.4. Fatty Acid Analysis

2.5. Tocol Analysis

2.6. Sterol Analysis

2.7. Oxidative Stability Evaluation

2.8. Texture Analysis

2.9. Sensory Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Determination of Fatty Acids

3.2. Determination of Tocols

3.3. Determination of Sterols

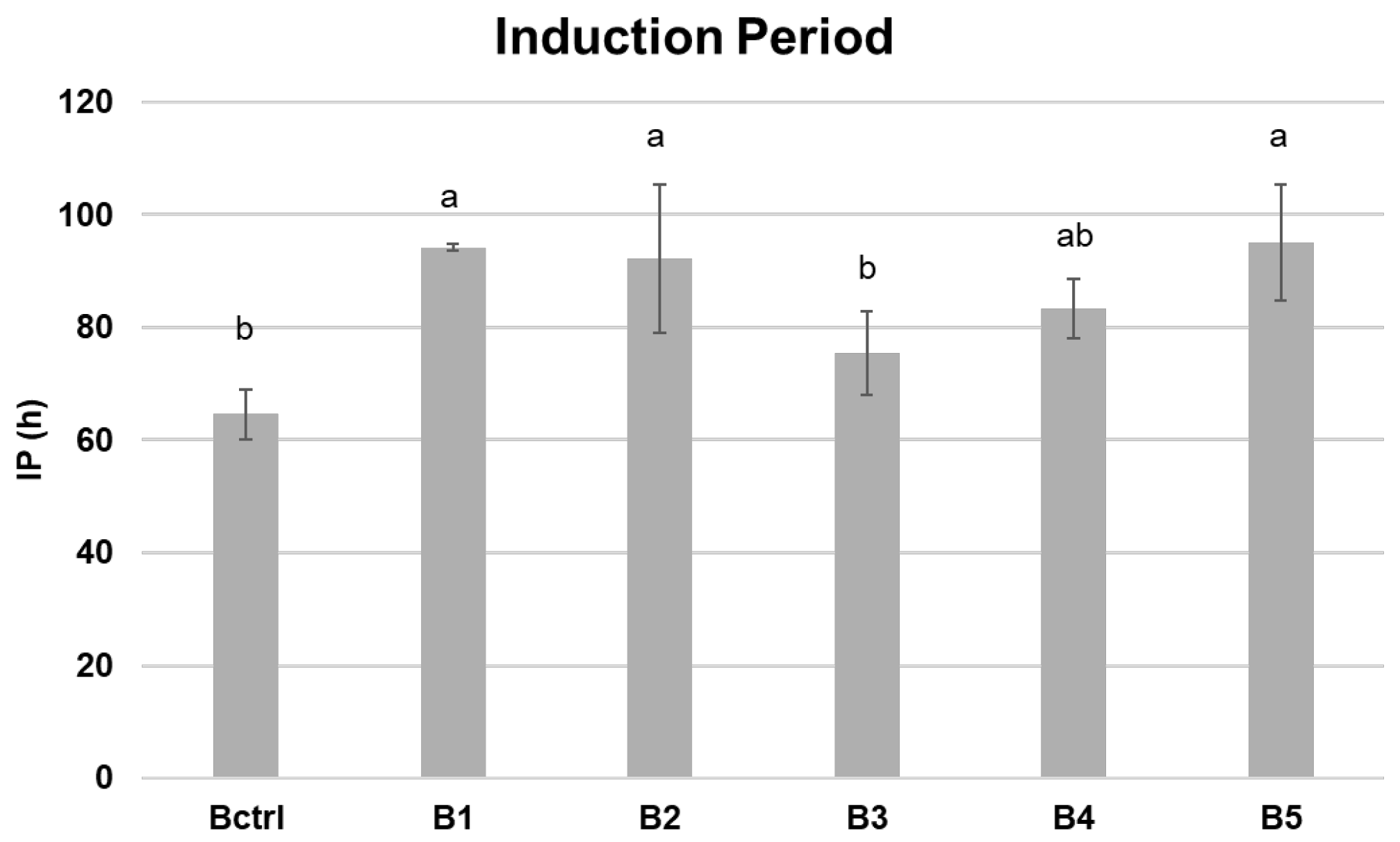

3.4. Oxidative Stability of Biscuits

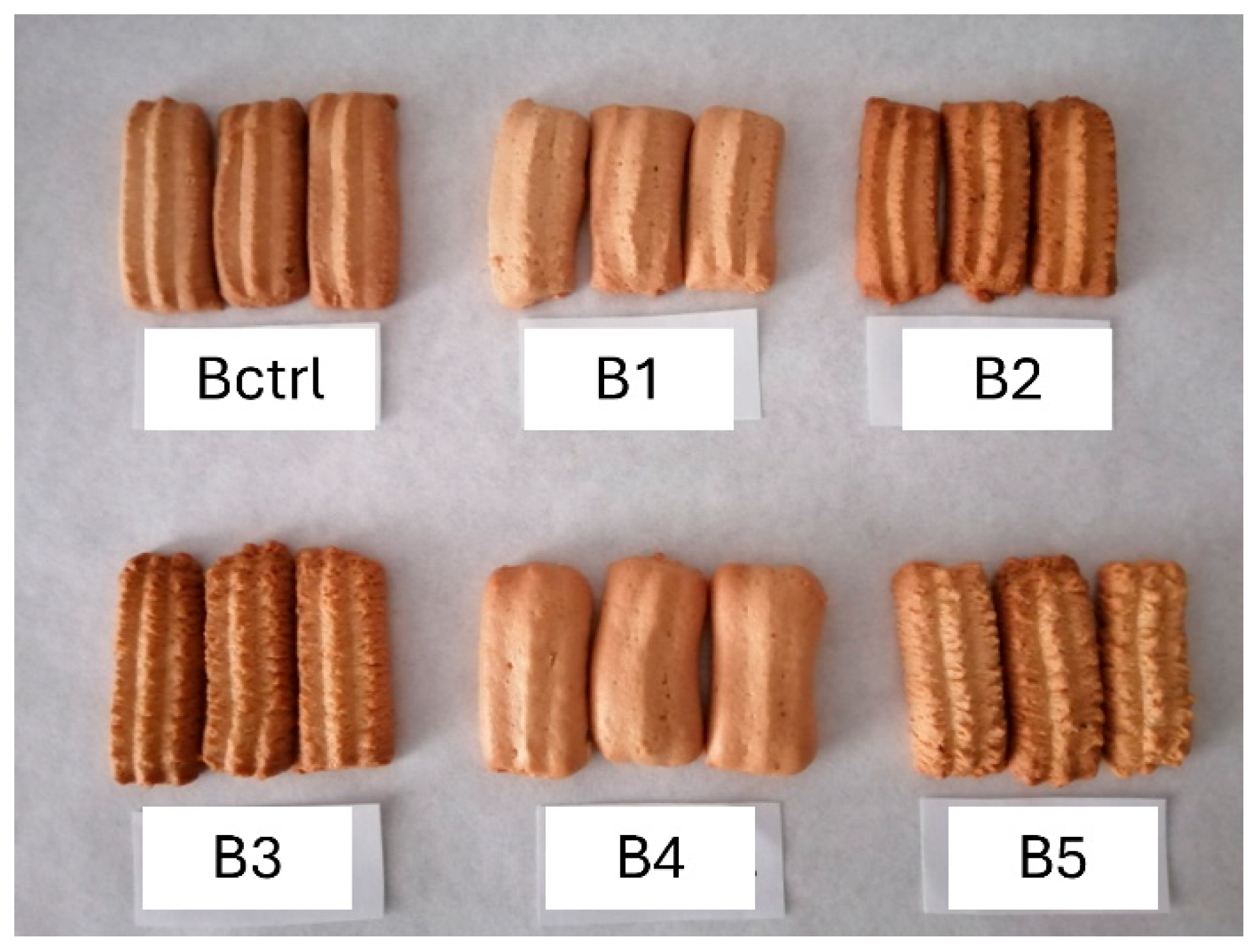

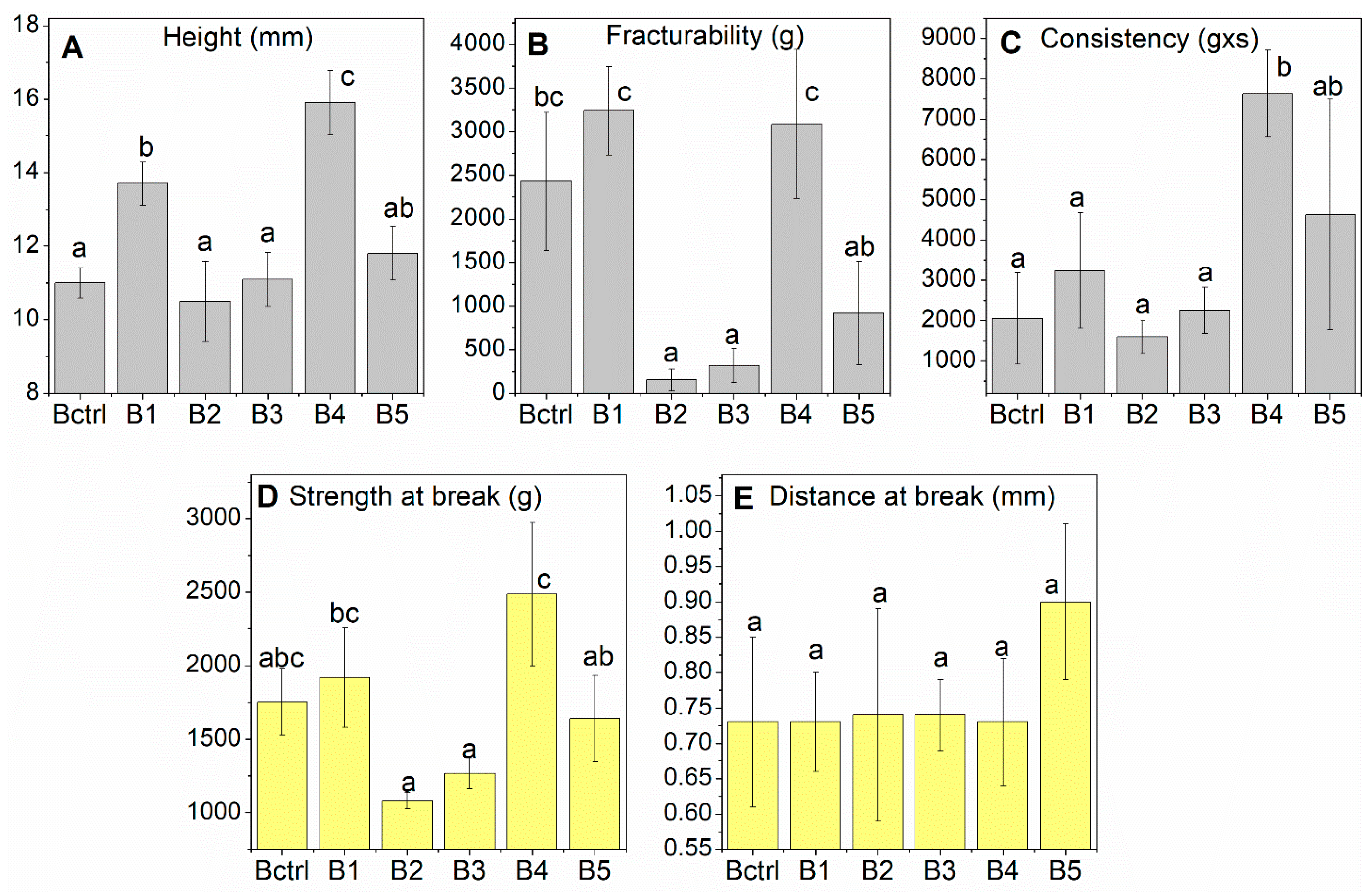

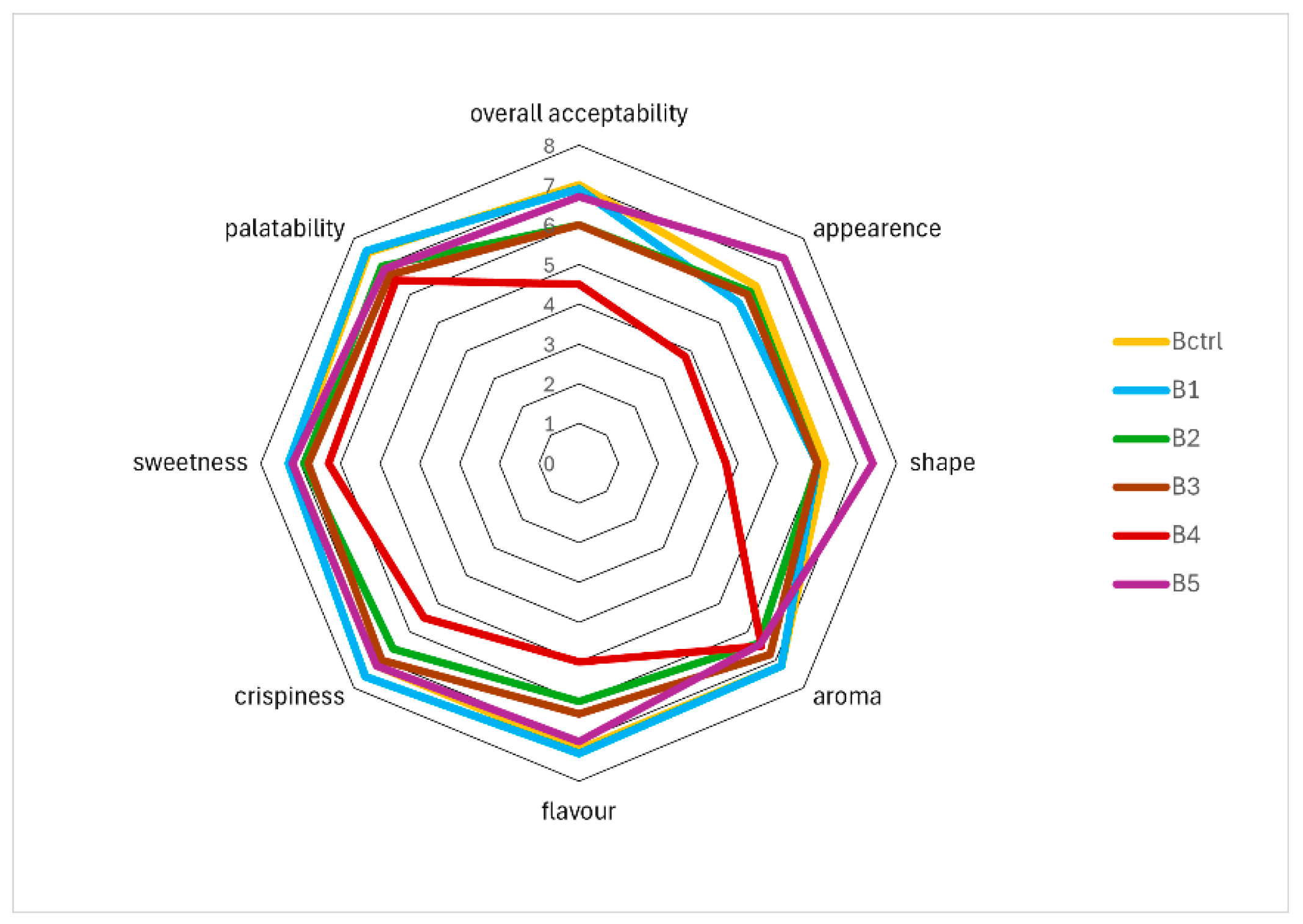

3.5. Texture and Sensory Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mamat, H.; Hill, S.E. Effect of fat types on the structural and textural properties of dough and semi-sweet biscuit. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 1998–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouhsari, F.; Saberi, F.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Kieliszek, M. Effect of the various fats on the structural characteristics of the hard dough biscuit. LWT 2022, 159, 113227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrè, A.M.; Caracciolo, M.; Capocasale, M.; Zappia, C.; Poiana, M. Effects of shortening replacement with extra virgin olive oil on the physical–chemical–sensory properties of Italian Cantuccini biscuits. Foods 2022, 11, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, G.; Li, Y.; Wanders, A.J.; Alssema, M.; Zock, P.L.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B.; Sun, Q. Intake of individual saturated fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease in US men and women: Two prospective longitudinal cohort studies. BMJ 2016, 355, i5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.J.; Barrera-Arellano, D.; Ribeiro, A.P.B. Margarines: Historical approach, technological aspects, nutritional profile, and global trends. Food Res. Int. 2021, 147, 110486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Passi, S.J.; Misra, A. Overview of trans fatty acids: Biochemistry and health effects. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2011, 5, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, G. Fats and oils as biscuit ingredients. In Manley’s Technology. Biscuits Crackers Cookies, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 160–180. [Google Scholar]

- Nor Aini, I.; Miskandar, M.S. Utilization of palm oil and palm products in shortenings and margarines. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2007, 109, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Santana, M.; Cagampang, G.B.; Nieves, C.; Cedeño, V.; MacIntosh, A.J. Use of high oleic palm oils in fluid shortenings and effect on physical properties of cookies. Foods 2022, 11, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrani, D.; Rao, G.V. Functions of ingredients in baking of sweet goods. In Food Engineering Aspects of Baking Sweet Goods, 1st ed.; Sumnu, S.G., Sahin, S., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sudha, M.L.; Srivastava, A.K.; Vetrimani, R.; Leelavathi, K. Fat replacement in soft dough biscuits: Its implications on dough rheology and biscuit quality. J. Food Eng. 2007, 80, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forker, A.; Zahn, S.; Rohm, H. A combination of fat replacers enables the production of fat-reduced shortdough biscuits with high-sensory quality. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2012, 5, 2497–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoulias, E.I.; Oreopoulou, V.; Kounalaki, E. Effect of fat and sugar replacement on cookie properties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2002, 82, 1637–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seker, I.T.; Ozboy-Ozbas, O.; Gokbulut, I.; Ozturk, S.; Koksel, H. Utilization of apricot kernel flour as fat replacer in cookies. J. Food Process Preserv. 2010, 34, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, A.; Seetharaman, K. Effect of a novel monoglyceride stabilized oil in water emulsion shortening on cookie properties. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 1476–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarancón, P.; Sanz, T.; Salvador, A.; Tárrega, A. Effect of fat on mechanical and acoustical properties of biscuits related to texture properties perceived by consumers. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2014, 7, 1725–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarancón, P.; Salvador, A.; Sanz, T.; Fiszman, S.; Tárrega, A. Use of healthier fats in biscuits (olive and sunflower oil): Changing sensory features and their relation with consumers’ liking. Food Res. Int. 2015, 69, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International Website. Available online: https://www.aoac.org (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Marzocchi, S.; Pasini, F.; Baldinelli, C.; Caboni, M.F. Value-addition of beef meat byproducts: Lipid characterization by chromatographic techniques. J. Oleo Sci. 2018, 67, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasini, F.; Marzocchi, S.; Ravagli, C.; Cuomo, F.; Messia, M.C.; Marconi, E.; Caboni, M.F. Effect of replacing olive oil with oil blends on physicochemical and sensory properties of taralli. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 2697–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, B.D.; Addis, P.B.; Park, S.W.; Smith, D.E. Quantification of cholesterol oxidation products in a variety of foods. J. Food Prot. 1989, 52, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeley, C.C.; Bentley, R.; Makita, M.; Wells, W.W. Gas– liquid chromatography of trimethylsilyl derivatives of sugars and related substances. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 2497–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenia, V.; Rodriguez-Estrada, M.T.; Baldacci, E.; Savioli, S.; Lercker, G. Analysis of cholesterol oxidation products by fast gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2012, 35, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelillo, M.; Iafelice, G.; Marconi, E.; Caboni, M.F. Identification of plant sterols in hexaploid and tetraploid wheats using gas chromatography with mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2003, 17, 2245–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzocchi, S.; Caboni, M.F. Study of the effect of tyrosyl oleate on lipid oxidation in a typical Italian bakery product. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 12555–12560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.S.; Prasanth Kumar, P.K.; Hemavathy, J.; Gopala Krishna, A.G. Fatty acid composition, oxidative stability, and radical scavenging activity of vegetable oil blends with coconut oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2009, 86, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.I.; Nurjanah, S.; Kramadibrata, A.M.; Naufalin, R.; Dwiyanti, H. Influence of different extraction methods on physic-chemical characteristics and chemical composition of coconut oil (Cocos nucifera L). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 250, 012102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlings, S. Coconuts and health: Different chain lengths of saturated fats require different consideration. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2020, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambiazi, R.C.; Przybylski, R.; Zambiazi, M.W.; Mendonça, C.B. Fatty acids composition of vegetable oils and fats. Bol. Cent. Pesq. Process. Alim. 2007, 25, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kostik, V.; Memeti, S.; Bauer, B. Fatty acid composition of edible oils and fats. J. Hyg. Eng. Des. 2013, 4, 112–116. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, M.; Abdurahman, H.; Ruoff, T.; Lehnert, K.; Vetter, W. Identification of aromatic fatty acids in butter fat. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91, 1695–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotor, A.A.; Rhazi, L. Effects of refining process on sunflower oil minor components: A review. OCL 2016, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belo, R.G.; Nolasco, S.; Mateo, C.; Izquierdo, N. Dynamics of oil and tocopherol accumulation in sunflower grains and its impact on final oil quality. Eur. J. Agron. 2017, 89, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Niki, E.; Noguchi, N. Comparative study on the action of tocopherols and tocotrienols as antioxidant: Chemical and physical effects. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2003, 123, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.; Theile, K.; Böhm, V. In vitro antioxidant activity of tocopherols and tocotrienols and comparison of vitamin E concentration and lipophilic antioxidant capacity in human plasma. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010, 54, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, H.; Ollilainen, V.; Piironen, V.; Lampi, A.M. Tocopherol, tocotrienol and plant sterol contents of vegetable oils and industrial fats. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2008, 21, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azrina, A.; Lim, P.H.; Amin, I.; Zulkhairi, A. Vitamin E and fatty acid composition of blended palm oils. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2009, 7, 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- Panfili, G.; Fratianni, A.; Irano, M. Normal Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Method for the Determination of Tocopherols and Tocotrienols in Cereals. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3940–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelsen, M.M.; Hansen, A. Tocopherol and Tocotrienol Content in Commercial Wheat Mill Stream. Cereal Chem. 2009, 86, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinazi, M.; Rodrigues Miranda Milagres, R.C.; Pinheiro-Sant’Ana, H.M.; Paes Chaves, J.B. Tocopherols and tocotrienols in vegetable oils and eggs. Quim. Nova 2009, 32, 2098–2103. [Google Scholar]

- Fratianni, A.; Di Criscio, T.; Mignogna, R.; Panfili, G. Carotenoids, tocols and retinols evolution during egg pasta–making processes. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skřivan, M.; Englmaierová, M. The deposition of carotenoids and α-tocopherol in hen eggs produced under a combination of sequential feeding and grazing. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2014, 190, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałązka-Czarnecka, I.; Korzeniewska, E.; Czarnecki, A.; Sójka, M.; Kiełbasa, P.; Dróżdź, T. Evaluation of quality of eggs from hens kept in caged and free-range systems using traditional methods and ultra-weak luminescence. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mba, O.I.; Dumont, M.J.; Ngadi, M. Thermostability and degradation kinetics of tocochromanols and carotenoids in palm oil, canola oil and their blends during deep-fat frying. LWT 2017, 82, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, G.; Cheng, W.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Shi, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S. Comparison and analysis of fatty acids, sterols, and tocopherols in eight vegetable oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 12493–12498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deme, T.; Haki, G.D.; Retta, N.; Woldegiorgis, A.; Geleta, M.; Mateos, H.; Lewandowski, P.A. Sterols as a biomarker in tracing niger and sesame seeds oils adulterated with palm oil. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aletor, O.; Famakin, F.M. Vitamins, amino acids, lipids and sterols of eggs from three different birds’ genotypes. IOSR J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 2017, 11, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derewiaka, D.; Pydyn, M. Quantitative Analysis of Sterols and Oxysterols in Foods by Gas Chromatography Coupled with Mass Spectrometry. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajhi, I.; Baccouri, B.; Mhadhbi, H. Phytosterols in Wheat: Composition, Contents and Role in Human Health. Open Access J. Biog. Sci. Res. 2020, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loskutov, I.G.; Khlestkina, E.K. Wheat, barley, and oat breeding for health benefit components in grain. Plants 2021, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piironen, V.; Lindsay, D.G.; Miettinen, T.A.; Toivo, J.; Lampi, A.M. Plant sterols: Biosynthesis, biological function and their importance to human nutrition. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000, 80, 939–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evtyugin, D.D.; Evtuguin, D.V.; Casal, S.; Domingues, M.R. Advances and challenges in plant sterol research: Fundamentals, analysis, applications and production. Molecules 2023, 28, 6526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareyt, B.; Brijs, K.; Delcour, J.A. Impact of fat on dough and cookie properties of sugar-snap cookies. Cereal Chem. 2010, 87, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regni, L.; Sdringola, P.; Torquati, B.; Evangelisti, N.; Chiorri, M.; Arcioni, L.; Proietti, P. A multidimensional approach to the decarbonization of the olive oil sector: Methodology proposal and case study. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 979, 179460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, J.H. Life cycle assessment of five vegetable oils. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namitha, V.V.; Raj, S.K.; Prathapan, K. Carbon Sequestration Potential in Coconut based Cropping System: A Review. Agric. Rev. 2022, 46, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, P.; Gupta, A.; Gopal, M.; Selvamani, V.; Mathew, J.; Surekha; Indhuja, S. Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.). In Soil Health Management for Plantation Crops; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 37–109. [Google Scholar]

| Samples | Composition of Fat Fraction |

|---|---|

| Bctrl | 100% Palm Oil (PO) |

| B1 | 100% Butter (B) |

| B2 | 50% Butter + 50% Extra Virgin Olive Oil (B:EVOO) |

| B3 | 50% Butter + 50% High-Oleic Sunflower Oil (B:HOSO) |

| B4 | 100% High-Oleic Sunflower Oil (HOSO) |

| B5 | 87.5% Coconut Oil + 12.5% Sunflower Oil (CO:SO) |

| FA | PO | B | B:EVOO (50:50) | B:HOSO (50:50) | HOSO | CO:SO (87.5:12.5) | Bctrl (PO) | B1 (B) | B2 (B:EVOO) | B3 (B:HOSO) | B4 (HOSO) | B5 (CO:SO) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C6:0 | n.d. | 1.8 ± 0.0 a | 0.8 ± 0.0 c | 0.7 ± 0.0 c | n.d. | 0.5 ± 0.0 e | n.d. | 1.7 ± 0.0 b | 0.7 ± 0.0 d | 0.7 ± 0.0 d | n.d. | 0.4 ± 0.0 e |

| C8:0 | n.d. | 1.1 ± 0.0 c | 0.5 ± 0.0 e | 0.5 ± 0.0 e | n.d. | 6.3 ± 0.0 a | n.d. | 1.0 ± 0.0 d | 0.4 ± 0.0 e | 0.4 ± 0.0 e | n.d. | 5.6 ± 0.0 b |

| C10:0 | n.d. | 2.7 ± 0.1 c | 1.2 ± 0.0 e | 1.2 ± 0.0 e | n.d. | 4.9 ± 0.0 a | n.d. | 2.5 ± 0.0 d | 1.1 ± 0.0 f | 1.0 ± 0.0 f | n.d. | 4.4 ± 0.0 b |

| C12:0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 f | 3.4± 0.1 c | 1.5 ± 0.0 e | 1.6 ± 0.0 e | n.d. | 40.2 ± 0.2 a | 0.4 ± 0.0 f | 3.2 ± 0.0 d | 1.4 ± 0.0 e | 1.4 ± 0.0 e | n.d. | 37.1 ± 0.1 b |

| C14:0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 h | 10.8 ± 0.1 c | 4.8 ± 0.0 e | 4.7 ± 0.0 e | n.d. | 15.3 ± 0.1 a | 0.9 ± 0.0 g | 10.1 ± 0.0 d | 4.3 ± 0.0 f | 4.3 ± 0.0 f | n.d. | 14.1 ± 0.1 b |

| C14:1 | n.d. | 1.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.5 ± 0.0 c | 0.5 ± 0.0 c | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.1 ± 0.0 b | 0.5 ± 0.0 c | 0.5 ± 0.0 c | n.d. | n.d. |

| C15:0 | n.d. | 1.0 ± 0.1 a | 0.5 ± 0.0 b | 0.5 ± 0.0 b | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.0 ± 0.0 a | 0.4 ± 0.0 b | 0.4 ± 0.0 b | n.d. | n.d. |

| C16:0 | 44.1 ± 0.1 a | 32.9 ± 0.2 c | 20.9 ± 0.0 f | 16.6 ± 0.0 h | 4.4 ± 0.0 n | 9.1 ± 0.0 l | 40.8 ± 0.1 b | 32.3 ± 0.0 d | 21.5 ± 0.1 e | 17.1 ± 0.1 g | 6.2 ± 0.0 m | 10.2 ± 0.0 i |

| C16:1c | 0.2 ± 0.0 e | 1.6 ± 0.0 a | 1.2 ± 0.0 b | 0.7 ± 0.0 c | 0.1 ± 0.0 e | n.d. | 0.3 ± 0.0 d | 1.6 ± 0.0 a | 1.2 ± 0.1 b | 0.8 ± 0.0 c | 0.3 ± 0.0 d | n.d. |

| C17:0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 c | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 0.3 ± 0.0 b | 0.2 ± 0.0 b | n.d. | n.d. | 0.1 ± 0.0 c | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 b | 0.2 ± 0.0 b | n.d. | n.d. |

| C17:1 | n.d. | 0.3 ± 0.0 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 b | 0.1 ± 0.0 c | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.2 ± 0.0 b | 0.2 ± 0.0 b | 0.2 ± 0.0 b | n.d. | n.d. |

| C18:0 | 4.0 ± 0.0 d | 10.0 ± 0.0 a | 6.0 ± 0.0 b | 5.7 ± 0.0 c | 2.6 ± 0.0 h | 2.9 ± 0.0 g | 4.1 ± 0.0 d | 9.9 ± 0.0 a | 6.0 ± 0.1 b | 5.9 ± 0.0 b | 3.0 ± 0.0 f | 3.3 ± 0.0 e |

| C18:1c9 | 41.4 ± 0.0 h | 27.3 ± 0.0 i | 55.3 ± 0.0 e | 58.7 ± 0.0 c | 83.1 ± 0.1 a | 11.1 ± 0.2 n | 41.9 ± 0.1 g | 26.8 ± 0.1 | 52.8 ± 0.2 f | 56.7 ± 0.1 d | 78.6 ± 0.1 b | 12.8 ± 0.0 m |

| C18:2n6 | 8.1 ± 0.0 f | 3.8 ± 0.2 l | 5.4 ± 0.1 i | 7.2 ± 0.0 g | 9.2 ± 0.1 e | 9.7 ± 0.1 d | 10.6 ± 0.1 c | 6.7 ± 0.1 h | 8.0 ± 0.1 f | 9.3 ± 0.1 de | 11.3 ± 0.0 b | 11.7 ± 0.1 a |

| C18:3n3 | 0.2 ± 0.0 e | 0.6 ± 0.0 b | 0.6 ± 0.0 b | 0.3 ± 0.0 d | 0.1 ± 0.0 f | 0.1 ±0.0 f | 0.4 ± 0.0 c | 0.7 ± 0.0 a | 0.7 ± 0.0 a | 0.4 ± 0.0 c | 0.2 ± 0.0 e | 0.2 ± 0.0 e |

| C20:0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 d | 0.8 ± 0.0 a | 0.3 ± 0.0 d | 0.4 ± 0.0 c | 0.2 ± 0.0 e | 0.1 ± 0.0 f | 0.3 ± 0.0 d | 0.7 ± 0.0 b | 0.4 ± 0.0 c | 0.4 ± 0.0 c | 0.2 ± 0.0 e | 0.1 ± 0.0 f |

| C20:1 | 0.1 ± 0.0 b | n.d. | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.1 ± 0.0 b | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | n.d. | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.1 ± 0.0 b |

| SFA | 49.9 ± 0.1 e | 65.3 ± 0.6 c | 36.6 ± 0.1 g | 32.2 ± 0.0 h | 7.3 ± 0.0 l | 79.1 ± 0.3 a | 46.7 ± 0.1 f | 62.7 ± 0.1 d | 36.4 ± 0.1 g | 32.0 ± 0.0 h | 9.3 ± 01 i | 75.3 ± 0.1 b |

| MUFA | 41.8 ± 0.0 h | 30.4 ± 0.3 i | 57.4 ± 0.0 e | 60.3 ± 0.1 c | 83.4 ± 0.1 a | 11.1 ± 0.2 n | 42.3 ± 0.1 g | 29.9 ± 0.2 l | 54.9 ± 0.1 f | 58.3 ± 0.0 d | 79.1 ± 0.0 b | 12.8 ± 0.0 m |

| PUFA | 8.3 ± 0.0 e | 4.4 ± 0.3 h | 6.0 ± 0.1 g | 7.5 ± 0.1 f | 9.3 ± 0.1 d | 9.8 ± 0.1 c | 11.0 ± 0.1 b | 7.4 ± 0.1 f | 8.7 ± 0.0 e | 9.7 ± 0.1 c | 11.6 ± 0.1 a | 11.9 ± 0.1 a |

| PO | B | B:EVOO (50:50) | B:HOSO (50:50) | HOSO | CO:SO (87.5:12.5) | Bctrl (PO) | B1 (B) | B2 (B:EVOO) | B3 (B:HOSO) | B4 (HOSO) | B5 (CO: SO) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-T | 19.7 ± 0.8 c | 2.7 ± 0.0 g | 16.4 ± 0.0 d | 19.6 ± 0.4 c | 27.7 ± 0.0 a | 10.2 ± 1.4 e | 17.5 ± 1.6 cd | 4.6 ± 0.1 f | 16.2 ± 0.6 d | 20.4 ± 1.7 bc | 22.0 ± 1.0 b | 12.5 ± 0.4 e |

| α-T3 | 21.2 ± 0.3 a | 0.1 ± 0.0 d | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 2.4 ± 0.3 c | 13.8 ± 2.0 b | 0.9 ± 0.1 c | 0.6 ± 0.1 c | 0.8 ± 0.1 c | 0.7 ± 0.1 c | 2.7 ± 0.0 c |

| β-T | n.d. | n.d. | 0.3 ± 0.0 c | 0.7 ± 0.0 b | 0.7 ± 0.0 b | 0.4 ± 0.2 b | 1.1 ± 0.2 ab | 1.2 ± 0.0 ab | 0.7 ± 0.0 b | 1.8 ± 0.3 a | 1.9 ± 0.6 a | 1.7 ± 0.1 a |

| γ-T | 3.3 ± 0.1 ab | 0.3 ± 0.0 d | 1.4 ± 0.0 cd | 1.2 ± 0.0 cd | 0.5 ± 0.1 d | 0.3 ± 0.1 d | 3.7 ± 0.8 a | 1.9 ± 0.1 c | 2.5 ± 0.2 abc | 2.3 ± 0.3 bc | 2.5 ± 0.6 abc | 2.1 ± 0.1 bc |

| β-T3 | 2.0 ± 0.0 b | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 4.9 ± 0.5 a | 4.5 ± 0.1 a | 3.9 ± 0.2 ab | 4.5 ± 0.3 a | 5.2 ± 1.1 a | 4.4 ± 0.2 a |

| γ-T3 | 25.9 ± 1.1 a | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 16.7 ± 1.9 b | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| δ-T3 | 8.2 ± 0.8 a | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 5.6 ± 0.4 a | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Total | 80.3 ± 3.2 a | 3.1 ± 0.1 f | 18.1 ± 0.1 de | 21.5 ± 0.3 de | 28.9 ± 0.1 d | 13.3 ± 1.1 e | 63.3 ± 7.4 b | 13.1 ± 0.2 e | 23.9 ± 1.1 de | 29.8 ± 2.7 d | 32.3 ± 3.3 c | 23.4 ± 0.9 de |

| PO | B | B:EVOO (50:50) | B:HOSO (50:50) | HOSO | CO:SO (87.5:12.5) | Bctrl (PO) | B1 (B) | B2 (B:EVOO) | B3 (B:HOSO) | B4 (HOSO) | B5 (CO: SO) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol | 2.1 ± 0.1 g | 228.9 ± 9.2 e | 110.3 ± 1.4 f | 105.3 ± 1.4 f | n.d. | n.d. | 236.4 ± 1.8 e | 525.6 ± 12.8 a | 414.3 ± 10.6 b | 409.4 ± 1.4 b | 294.9 ± 0.8 d | 324.6 ± 2.3 c |

| Campesterol | 26.0 ± 0.6 ab | n.d. | 7.5 ± 0.1 d | 9.5 ± 0.1 c | 20.4 ± 0.2 b | 8.8 ± 0.4 cd | 29.3 ± 0.4 a | 12.7 ± 2.6 c | 20.2 ± 1.0 b | 21.2 ± 3.3 b | 30.9 ± 1.5 a | 10.2 ± 0.6 c |

| Campestanol | n.d. | n.d. | 4.0 ± 0.2 b | 2.4 ± 0.1 b | 5.5 ± 0.5 b | 3.3 ± 0.0 b | 3.2 ± 0.5 b | n.d. | 10.0 ± 3.7 a | 5.5 ± 0.6 b | 6.8 ± 0.1 ab | 3.9 ± 0.4 b |

| Stigmasterol | 11.2 ± 0.4 b | n.d. | n.d. | 6.5 ± 0.1 c | 13.5 ± 0.6 b | 10.6 ± 1.4 b | 13.2 ± 0.4 b | n.d. | n.d. | 6.8 ± 0.4 c | 16.7 ± 0.0 a | 11.3 ± 1.4 b |

| β-Sitosterol | 43.9 ± 0.9 e | 15.4 ± 0.2 f | 56.9 ± 2.0 de | 67.2 ± 2.0 d | 139.8 ± 1.1 ab | 95.3 ± 3.4 c | 77.4 ± 0.2 e | 46.7 ± 0.4 e | 91.0 ± 2.1 c | 98.1 ± 3.3 bc | 163.6 ± 1.0 a | 120.0 ± 0.5 b |

| Sitostanol | n.d. | n.d. | 4.4 ± 0.2 cd | 4.3 ± 0.1 cd | 9.3 ± 0.3 a | 2.5 ± 0.1 d | 5.9 ± 0.8 bcd | 9.0 ± 0.3 ab | 11.2 ± 0.8 a | 8.2 ± 1.8 abc | 11.5 ± 1.3 a | 8.8 ± 1.9 ab |

| Δ5-Avenasterol | n.d. | n.d. | 4.6 ± 0.0 c | 4.6 ± 0.4 c | 8.0 ± 0.1 b | 13.2 ± 1.4 a | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 9.3 ± 0.7 b | 5.0 ± 0.0 c |

| Δ7-Avenasterol | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 4.0 ± 0.0 c | 8.1 ± 0.1 b | 6.1 ± 0.2 bc | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 13.0 ± 1.5 a | n.d. |

| Total phytosterols | 81.1 ± 0.3 e | 15.4 ± 0.2 g | 77.4 ± 2.5 ef | 98.5 ± 0.7 de | 204.6 ± 1.3 b | 139.8 ± 6.2 c | 129.0 ± 1.0 d | 68.4 ± 0.6 f | 132.4 ± 2.1 cd | 139.8 ± 1.4 cd | 251.8 ± 1.2 a | 159.2 ± 1.5 c |

| Total sterols | 83.2 ± 0.5 i | 244.3 ± 9.4 e | 187.7 ± 3.5 g | 203.8 ± 1.0 f | 204.6 ± 1.3 f | 139.8 ± 6.2 h | 365.4 ± 1.8 d | 594.0 ± 5.9 a | 546.7 ± 1.1 b | 549.2 ± 0.4 b | 546.7 ± 1.0 b | 483.8 ± 1.3 c |

| F-Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor | Samples (S) | Judges (J) | Replicates (R) | S × J | J × R | S × R |

| Aroma | 17.8 * | 2.7 * | 0.1 ns | 12.8 * | 1.0 ns | 0.5 ns |

| Aroma of lemon | 22.6 * | 19.4 * | 0.9 ns | 10.7 * | 0.2 ns | 0.3 ns |

| Flavour | 9.8 * | 2.1 * | 0.4 ns | 22.2 * | 1.2 ns | 0.4 ns |

| Flavour of cereal | 41.2 * | 23.1 * | 0.3 ns | 14.6 * | 0.8 ns | 0.8 ns |

| Flavour of lemon | 21.7 * | 54.9 * | 0.2 ns | 12.8 * | 1.1 ns | 1.1 ns |

| Crispiness | 37.1 * | 7.3 * | 4.1 * | 19.6 * | 0.7 ns | 2.0 ns |

| Consistency | 14.7 * | 54.8 * | 4.1 * | 12.8 * | 0.3 ns | 1.9 ns |

| Friability | 59.8 * | 38.0 * | 0.3 ns | 14.1 * | 0.4 ns | 0.5 ns |

| Fat perception | 8.3 * | 71.3 * | 3.4 ns | 12.8 * | 0.7 ns | 1.5 ns |

| Sweetness | 4.8 * | 36.9 * | 6.8 ns | 8.6 * | 0.4 ns | 1.4 ns |

| Attributes | Samples | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bctrl | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | |

| Aroma | 4.90 b | 5.20 b | 4.15 a | 4.80 b | 5.00 b | 5.55 c |

| Aroma of lemon | 5.35 c | 5.20 c | 4.40 b | 4.45 b | 4.40 b | 4.05 a |

| Flavour | 5.00 b | 4.85 b | 4.35 a | 5.25 b | 4.85 b | 5.05 b |

| Flavour of cereal | 4.80 a | 4.95 a | 5.30 b | 5.00 a | 6.10 c | 4.95 a |

| Flavour of lemon | 4.70 c | 3.75 a | 4.10 b | 4.15 b | 5.10 c | 4.10 b |

| Crispiness | 4.70 a | 4.90 a | 5.55 b | 5.50 b | 4.55 a | 5.35 b |

| Consistency | 4.50 a | 4.70 a | 4.95 b | 4.95 b | 5.20 c | 4.55 a |

| Friability | 5.35 b | 4.75 a | 5.25 b | 5.35 b | 6.65 c | 5.55 c |

| Fat perception | 5.00 b | 5.00 b | 5.05 b | 5.05 b | 5.35 c | 4.75 a |

| Sweetness | 4.70 a | 4.95 a | 4.75 a | 4.75 a | 4.55 a | 4.95 a |

| Palatability | 4.95 b | 4.95 b | 4.55 a | 4.55 a | 4.50 a | 4.50 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marzocchi, S.; Ravagli, C.; Cuomo, F.; Messia, M.C.; Marconi, E.; Caboni, M.F.; Pasini, F. How Different Lipid Blends Affect the Quality and Sensory Attributes of Short Dough Biscuits. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12679. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312679

Marzocchi S, Ravagli C, Cuomo F, Messia MC, Marconi E, Caboni MF, Pasini F. How Different Lipid Blends Affect the Quality and Sensory Attributes of Short Dough Biscuits. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12679. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312679

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarzocchi, Silvia, Cesare Ravagli, Francesca Cuomo, Maria Cristina Messia, Emanuele Marconi, Maria Fiorenza Caboni, and Federica Pasini. 2025. "How Different Lipid Blends Affect the Quality and Sensory Attributes of Short Dough Biscuits" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12679. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312679

APA StyleMarzocchi, S., Ravagli, C., Cuomo, F., Messia, M. C., Marconi, E., Caboni, M. F., & Pasini, F. (2025). How Different Lipid Blends Affect the Quality and Sensory Attributes of Short Dough Biscuits. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12679. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312679