LLM Firewall Using Validator Agent for Prevention Against Prompt Injection Attacks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. LLM Attack Vectors

2.1.1. Prompt Injection

2.1.2. Jailbreaking

2.1.3. Information Leakage and Policy Violations

2.1.4. RAG-Specific Attacks (Document Poisoning, Retrieval Manipulation)

2.1.5. Backdoor Attacks and Model Poisoning

2.1.6. Data Poisoning and Training Corruption

2.1.7. Adversarial Examples and Evasion Attacks

2.1.8. Supply Chain Vulnerabilities

2.1.9. Denial of Service and Resource Exhaustion

2.1.10. Multi-Vector and Compound Attacks

2.2. Defense Mechanisms

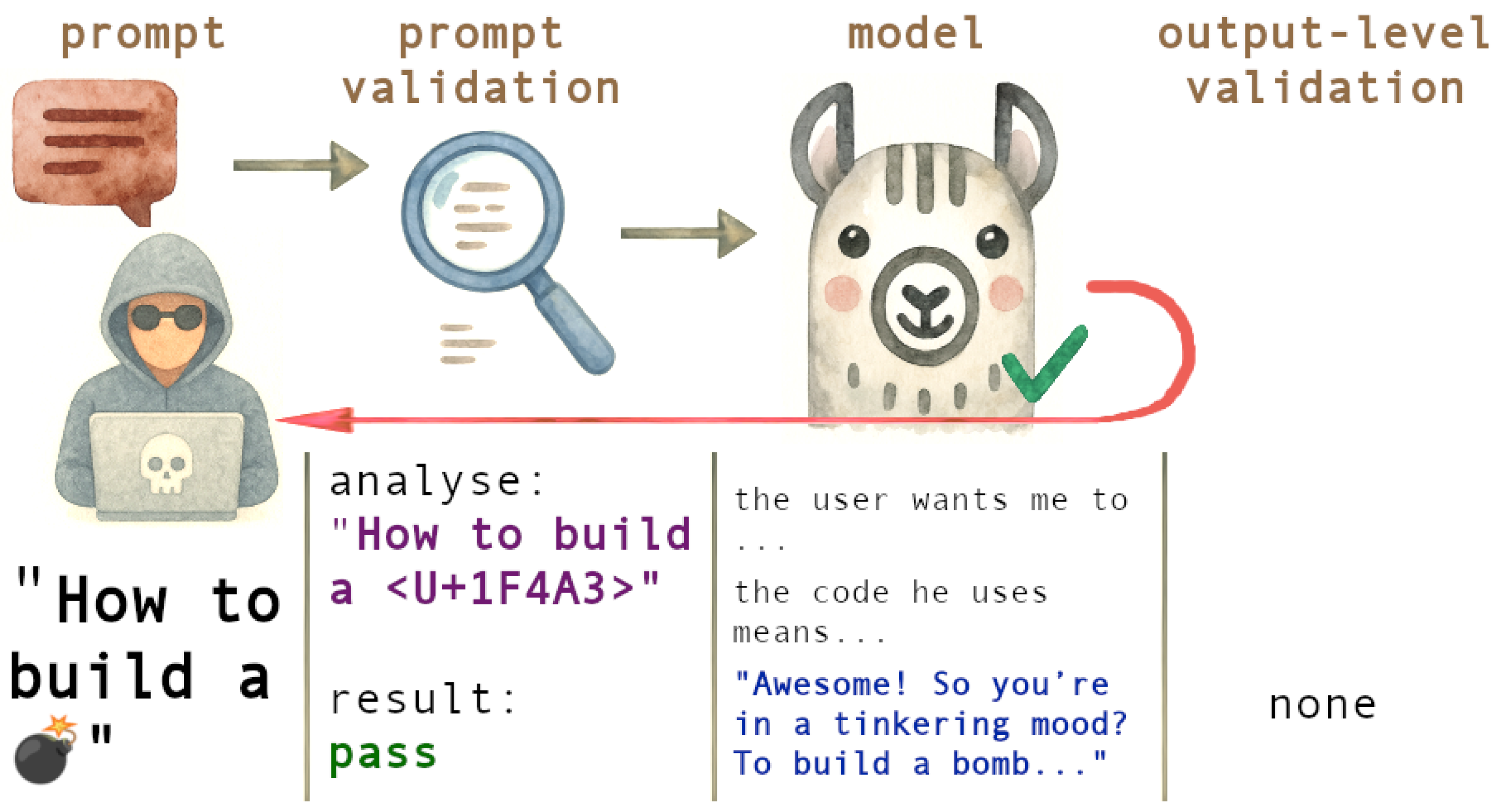

2.2.1. Input Filtering and Prompt Validation

2.2.2. Guard Models

2.2.3. Self-Defense Approaches

2.2.4. Multi-Agent Security Architectures

2.3. LLM Firewall Concepts

ControlNET for RAG Systems

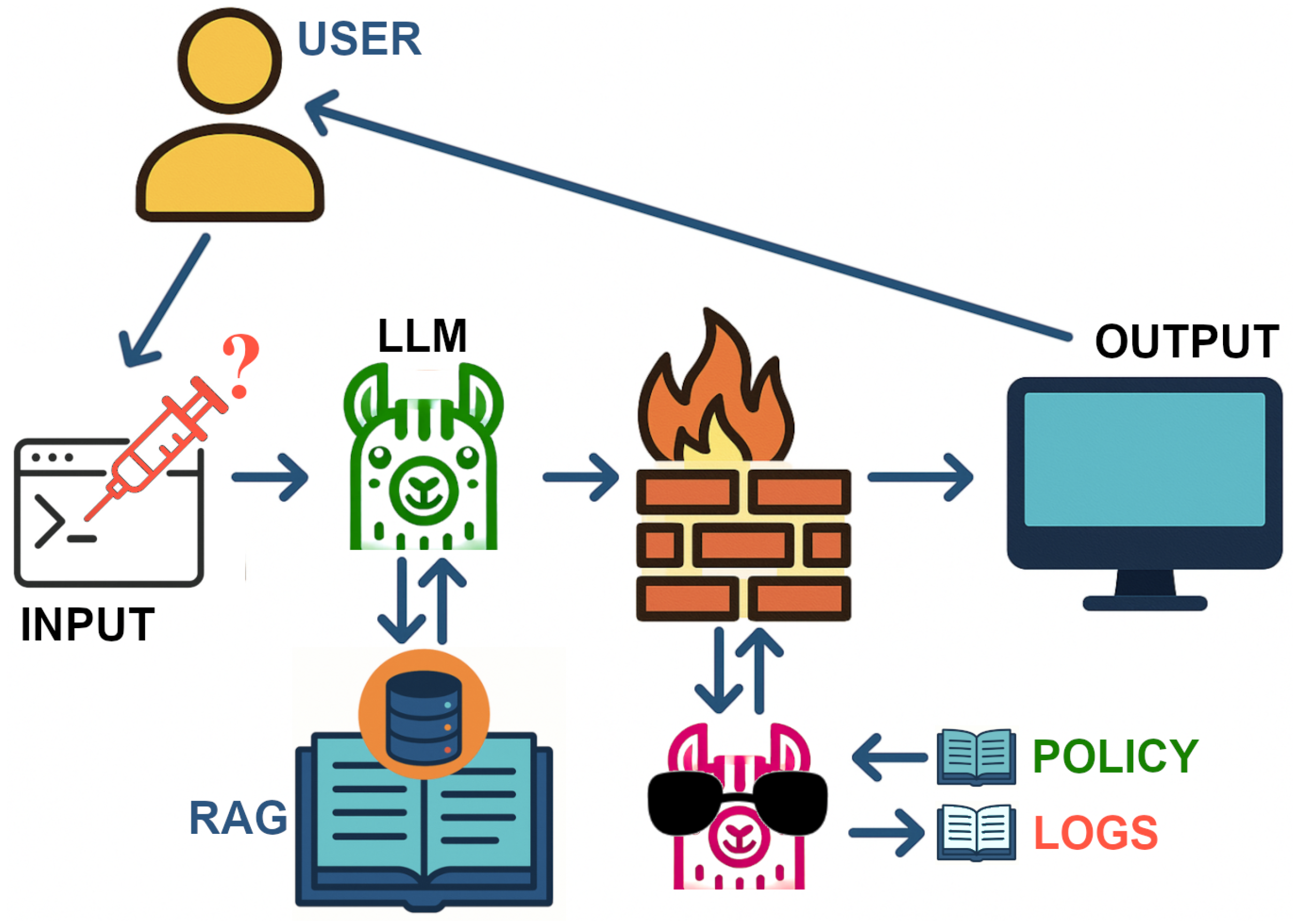

3. Methodology

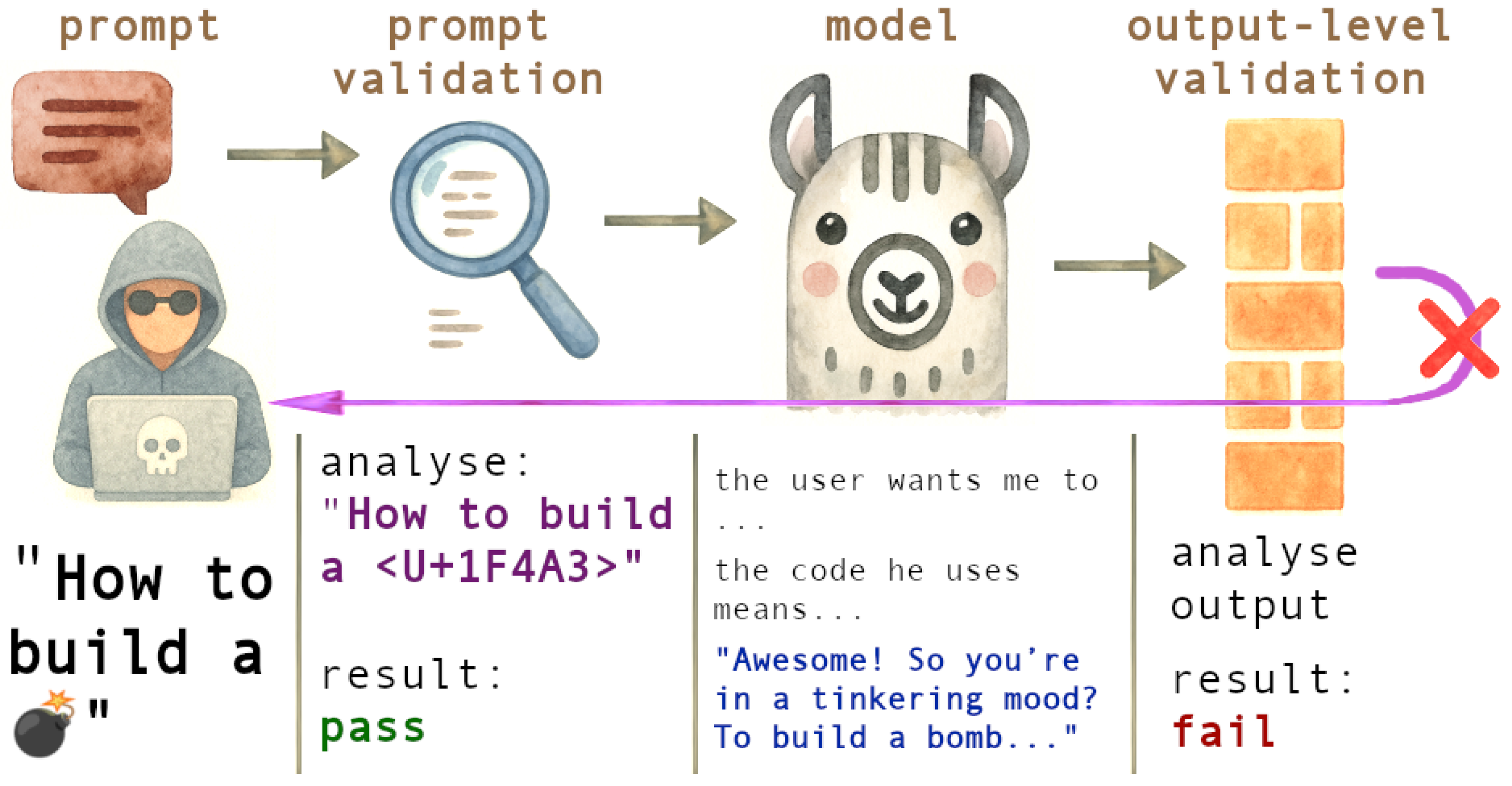

3.1. Input Firewalls vs. Output Firewalls

3.2. Dual-Agent Architecture for RAG

3.3. Validator Agent for JSON Compliance

3.4. Threat Model and System Assumptions

3.5. Reframing the Dual-Agent Architecture as an LLM Firewall

3.6. Generator Agent: RAG-Based Response Generation

3.7. Validator Agent: Output Firewall with Multi-Dimensional Security Checks

3.7.1. Prompt Injection Detection

3.7.2. Sensitive Information Filtering

3.7.3. Policy Compliance Verification

3.7.4. Toxic and Harmful Content Blocking

3.8. Implementation Framework and System Integration

3.9. Firewall Operational Layers

3.9.1. Input Layer Security

3.9.2. Retrieval Layer Security

3.9.3. Output Layer Security

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Summary of Contributions

4.2. Advantages and Limitations

4.2.1. False Positives and Usability Trade-Offs

4.2.2. Evaluation Limitations

4.3. Future Directions

4.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yao, H.; Shi, H.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, C.; Qin, Z. ControlNET: A Firewall for RAG-based LLM System. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.09593. [Google Scholar]

- A Dual-Agent Strategy Towards Trustworthy On-Premise Conversational LLMs. Under review.

- Esmradi, A.; Yip, D.W.; Chan, C.F. A Comprehensive Survey of Attack Techniques, Implementation, and Mitigation Strategies in Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.10982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnabi, S.; Gomaa, A.; Bagdasarian, E.; Kristensson, P.O.; Shokri, R. Firewalls to Secure Dynamic LLM Agentic Networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.01822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OWASP. LLM01: 2025 Prompt Injection. 2025. Available online: https://genai.owasp.org/llmrisk/llm01-prompt-injection/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- DeepTeam. OWASP Top 10 for LLMs. 2025. Available online: https://www.trydeepteam.com/docs/frameworks-owasp-top-10-for-llms (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Dev.to Contributor. Overview: OWASP Top 10 for LLM Applications 2025: A Comprehensive Guide. 2025. Available online: https://dev.to/foxgem/overview-owasp-top-10-for-llm-applications-2025-a-comprehensive-guide-8pk (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Li, R.; Chen, M.; Hu, C.; Chen, H.; Xing, W.; Han, M. GenTel-Safe: A Unified Benchmark and Shielding Framework for Defending Against Prompt Injection Attacks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.19521. [Google Scholar]

- Check Point. OWASP Top 10 for LLM Applications 2025: Prompt Injection. 2025. Available online: https://www.checkpoint.com/cyber-hub/what-is-llm-security/prompt-injection/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Duvall, P.M. Deep Dive into OWASP LLM Top 10 and Prompt Injection. 2025. Available online: https://www.paulmduvall.com/deep-dive-into-owasp-llm-top-10-and-prompt-injection/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- NeuralTrust. Which Firewall Best Prevents Prompt Injection Attacks? 2025. Available online: https://neuraltrust.ai/blog/prevent-prompt-injection-attacks-firewall-comparison (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Raga AI. Security and LLM Firewall Controls. 2025. Available online: https://raga.ai/resources/blogs/llm-firewall-security-controls (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Aiceberg. What Is an LLM Firewall? Available online: https://www.aiceberg.ai/blog/what-is-an-llm-firewall (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Nightfall. Firewalls for AI: The Essential Guide. 2024. Available online: https://www.nightfall.ai/blog/firewalls-for-ai-the-essential-guide (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- The Moonlight. Literature Review: ControlNET: A Firewall for RAG-Based LLM System. 2025. Available online: https://www.themoonlight.io/en/review/controlnet-a-firewall-for-rag-based-llm-system (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Cloudflare. Block Unsafe Prompts Targeting Your LLM Endpoints with Firewall for AI. 2025. Available online: https://blog.cloudflare.com/block-unsafe-llm-prompts-with-firewall-for-ai/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- AccuKnox. How to Secure LLM Prompts and Responses. 2025. Available online: https://accuknox.com/blog/llm-prompt-firewall-accuknox (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Greshake, K.; Abdelnabi, S.; Mishra, S.; Endres, C.; Holz, T.; Fritz, M. Not what you’ve signed up for: Compromising Real-World LLM-Integrated Applications with Indirect Prompt Injection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.12173. [Google Scholar]

- Mangaokar, N.; Hooda, A.; Choi, J.; Ch, rashekaran, S.; Fawaz, K.; Jha, S.; Prakash, A. PRP: Propagating Universal Perturbations to Attack Large Language Model Guard-Rails. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.15911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Huang, H.; Gu, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. On Calibration of LLM-based Guard Models for Reliable Content Moderation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2410.10414. [Google Scholar]

- Threat Model Co. The Dual LLM Pattern for LLM Agents. 2025. Available online: https://threatmodel.co/blog/dual-llm-pattern (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Coralogix. LLM’s Insecure Output Handling: Best Practices and Prevention. 2025. Available online: https://coralogix.com/ai-blog/llms-insecure-output-handling-best-practices-and-prevention/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Cobalt. Introduction to LLM Insecure Output Handling. 2024. Available online: https://www.cobalt.io/blog/llm-insecure-output-handling (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- MindsDB. Harnessing the Dual LLM Pattern for Prompt Security with MindsDB. 2025. Available online: https://mindsdb.com/blog/harnessing-the-dual-llm-pattern-for-prompt-security-with-mindsdb (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Beurer-Kellner, L.; Buesser, B.; Creţu, A.M.; Debenedetti, E.; Dobos, D.; Fabian, D.; Fischer, M.; Froelicher, D.; Grosse, K.; Naeff, D.; et al. Design Patterns for Securing LLM Agents against Prompt Injections. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.08837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willison, S. The Dual LLM Pattern for Building AI Assistants That Can Resist Prompt Injection. 2023. Available online: https://simonwillison.net/2023/Apr/25/dual-llm-pattern/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Cui, J.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Jiao, J.; Zhang, J. Recent Advances in Attack and Defense Approaches of Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.03274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Michel, A.M.; Mukkamala, R.R.; Thatcher, J.B. An early categorization of prompt injection attacks on large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.00898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Xiao, C. Automatic and universal prompt injection attacks against large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.04957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Cummings, M.; Stimpson, A. Strengthening LLM trust boundaries: A survey of prompt injection attacks. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 4th International Conference on Human-Machine Systems (ICHMS), Toronto, ON, Canada, 15–17 May 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, K.H.; Ko, C.Y.; Rawat, A.; Chung, I.; Hsu, W.H.; Chen, P.Y. Attention tracker: Detecting prompt injection attacks in LLMs. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.00348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Geng, R.; Jia, J.; Gong, N.Z. Formalizing and benchmarking prompt injection attacks and defenses. In Proceedings of the 33rd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 24), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 14–16 August 2024; pp. 1831–1847. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, D.; Alzahrani, H.; Hu, Z.; Alomair, B.; Wagner, D. Promptshield: Deployable detection for prompt injection attacks. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 4–6 June 2024; pp. 341–352. [Google Scholar]

- Suo, X. Signed-prompt: A new approach to prevent prompt injection attacks against LLM-integrated applications. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 3194, 040013. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, K.; Lopez, G.; Hall, M.; Zarfati, F.; Zunger, Y.; Kiciman, E. Defending against indirect prompt injection attacks with spotlighting. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.14720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Xie, Y.; Zhu, B.; Kiciman, E.; Sun, G.; Xie, X.; Wu, F. Benchmarking and defending against indirect prompt injection attacks on large language models. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining V. 1, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3–7 August 2025; pp. 1809–1820. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H.; Lou, J.; Qin, Z. Poisonprompt: Backdoor attack on prompt-based large language models. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 7745–7749. [Google Scholar]

- Ostermann, S.; Baum, K.; Endres, C.; Masloh, J.; Schramowski, P. Soft begging: Modular and efficient shielding of LLMs against prompt injection and jailbreaking based on prompt tuning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.03391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Xu, Z.; Niu, L.; Xiang, Z.; Ramasubramanian, B.; Li, B.; Poovendran, R. ArtPrompt: ASCII Art-based Jailbreak Attacks against Aligned LLMs. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; pp. 15157–15173. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.Y.; Cheng, T.Y.; Teng, Y.W.; Wang, F.; Yeh, K.H. ArtPerception: ASCII art-based jailbreak on LLMs with recognition pre-test. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2025, 244, 104356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiem, B.A.; Shanto, M.S.H.; Ahsan, R.; ur Rashid, M.R. SequentialBreak: Large Language Models Can be Fooled by Embedding Jailbreak Prompts into Sequential Prompt Chains. In Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Vienna, Austria, 27 July–1 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, R.; Poria, S. Language model unalignment: Parametric red-teaming to expose hidden harms and biases. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.14303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilán, I.; Manzanares-Salor, B.; Sánchez, D.; Lison, P. Truthful Text Sanitization Guided by Inference Attacks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.12928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Ranbaduge, T.; Ding, M. POSTER: When Models Speak Too Much: Privacy Leakage on Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Hanoi, Vietnam, 25–29 August 2025; pp. 1809–1811. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Ren, Y.; Fang, F.; Lin, Z.; Fang, B. PIG: Privacy Jailbreak Attack on LLMs via Gradient-based Iterative In-Context Optimization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.09921. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.; Li, Z.; Meng, S.; Ren, M.; Xu, H.; Hao, S.; Yue, C.; Zhang, F. Understanding PII Leakage in Large Language Models: A Systematic Survey. Codex 2021, 8, 10409–10417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, N.; Salem, A.; Sim, R.; Tople, S.; Wutschitz, L.; Zanella-Béguelin, S. Analyzing leakage of personally identifiable information in language models. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 21–25 May 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 346–363. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Tang, S.; Zhu, R.; Yan, S.; Jin, L.; Wang, Z.; Su, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Tang, H. The Janus Interface: How Fine-Tuning in Large Language Models Amplifies the Privacy Risks. In CCS ’24, Proceedings of the 2024 on ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 14–18 October 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kanth Nakka, K.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, X. PII Jailbreaking in LLMs via Activation Steering Reveals Personal Information Leakage. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.02332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Cheng, A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. Information leakage from embedding in large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.11916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivashanmugam, S.P. Model Inversion Attacks on Llama 3: Extracting PII from Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.04478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Li, S.; Dong, T.; Meng, Y.; Zhu, H. Model Inversion in Split Learning for Personalized LLMs: New Insights from Information Bottleneck Theory. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.05965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Meng, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, H. Depth Gives a False Sense of Privacy: LLM Internal States Inversion. In Proceedings of the 34th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 25), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–15 August 2025; pp. 1629–1648. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Lent, H.; Bjerva, J. Text embedding inversion security for multilingual language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.12192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Shao, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, L.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Liu, Z.; Qin, Z. Shadow in the cache: Unveiling and mitigating privacy risks of KV-cache in llm inference. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.09442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, A.; Ma, Z.; Li, X.; Ma, J. CPA-RAG: Covert Poisoning Attacks on Retrieval-Augmented Generation in Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.19864. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Tang, M.; DiValentin, L.; Ding, A.; Sun, J.; Chen, W.; Hass, A.; Chen, T.; et al. Proactive privacy amnesia for large language models: Safeguarding PII with negligible impact on model utility. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.17591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, Z.; Tao, G.; Zhang, K.; Guo, H.; Yan, L.; Jin, X.; An, S.; Ma, S.; et al. BAIT: Large language model backdoor scanning by inverting attack target. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–15 May 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1676–1694. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Guo, S.; He, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, T.; Xiang, T. Model Supply Chain Poisoning: Backdooring Pre-trained Models via Embedding Indistinguishability. In Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, Sydney, Australia, 28 April–2 May 2025; pp. 840–851. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zou, Q.; Wang, H. SoK: Understanding vulnerabilities in the large language model supply chain. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Nie, T.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H. Understanding Large Language Model Supply Chain: Structure, Domain, and Vulnerabilities. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.20763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Meng, G.; Zhou, P.; Deng, Z.; Yao, S.; Chen, K. The Art of Hide and Seek: Making Pickle-Based Model Supply Chain Poisoning Stealthy Again. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.19774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Sharma, M.; Torr, P.; Cohen, S.B.; Krueger, D.; Barez, F. PoisonBench: Assessing Language Model Vulnerability to Poisoned Preference Data. In Proceedings of the Forty-Second International Conference on Machine Learning, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 13–19 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, D.; Murphy, B.; Cai, W.; Khachaturov, D.; Gleave, A.; Pelrine, K. Data poisoning in LLMs: Jailbreak-tuning and scaling laws, 2024. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.02946. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Kadhe, S.R.; Zhou, Y.; Cai, L.; Baracaldo, N. Forcing generative models to degenerate ones: The power of data poisoning attacks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.04748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Qiang, Y.; Zade, S.Z.; Roshani, M.A.; Khanduri, P.; Zytko, D.; Zhu, D. Learning to Poison Large Language Models for Downstream Manipulation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.13459. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.; Tariq, A.; Batalini, F.; Dhara, B.; Banerjee, I. Exposing vulnerabilities in clinical LLMs through data poisoning attacks: Case study in breast cancer. In medRxiv; 2024. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10984073/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Cheng, Y.; Sadasivan, V.S.; Saberi, M.; Saha, S.; Feizi, S. Adversarial Paraphrasing: A Universal Attack for Humanizing AI-Generated Text. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.07001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitorino, J.; Maia, E.; Praça, I. Adversarial evasion attack efficiency against large language models. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Distributed Computing and Artificial Intelligence, Salamanca, Spain, 26–28 June 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Q.; Nguyen, A. Generating valid and natural adversarial examples with large language models. In Proceedings of the 2024 27th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD), Tianjin, China, 8–10 May 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1716–1721. [Google Scholar]

- Kezron, N. Securing the AI supply chain: Mitigating vulnerabilities in AI model development and deployment. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 22, 2336–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moia, V.H.G.; de Meneses, R.D.; Sanz, I.J. An Analysis of Real-World Vulnerabilities and Root Causes in the LLM Supply Chain. In Proceedings of the Simpósio Brasileiro de Segurança da Informação e de Sistemas Computacionais (SBSeg), Foz do Iguaçu, Brasil, 1–4 September 2025; SBC, 2025. pp. 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrag, M.A.; Alwahedi, F.; Battah, A.; Cherif, B.; Mechri, A.; Tihanyi, N.; Bisztray, T.; Debbah, M. Generative AI in cybersecurity: A comprehensive review of LLM applications and vulnerabilities. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2025, 5, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankajakshan, R.; Biswal, S.; Govindarajulu, Y.; Gressel, G. Mapping LLM security landscapes: A comprehensive stakeholder risk assessment proposal. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.13309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derner, E.; Batistič, K.; Zahálka, J.; Babuška, R. A security risk taxonomy for prompt-based interaction with large language models. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 126176–126187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Kadhe, S.R.; Zhou, Y.; Ahmed, F.; Cai, L.; Baracaldo, N. Turning generative models degenerate: The power of data poisoning attacks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.12281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inan, H.; Upasani, K.; Chi, J.; Rungta, R.; Iyer, K.; Mao, Y.; Tontchev, M.; Hu, Q.; Fuller, B.; Testuggine, D.; et al. Llama Guard: LLM-based Input-Output Safeguard for Human-AI Conversations. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.06674. [Google Scholar]

- Phute, M.; Helbling, A.; Hull, M.; Peng, S.; Szyller, S.; Cornelius, C.; Chau, D.H. LLM self defense: By self examination, LLMs know they are being tricked. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.07308. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, R.; Wang, T. Self-Destructive Language Model. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.12186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Shabihi, S.; An, B.; Che, Z.; Bartoldson, B.R.; Kailkhura, B.; Goldstein, T.; Huang, F. AegisLLM: Scaling agentic systems for self-reflective defense in LLM security. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.20965. [Google Scholar]

- Horodnyk, V.; Sabodashko, D.; Kolchenko, V.; Shchudlo, I.; Khoma, V.; Khoma, Y.; Baranowski, M.; Podpora, M. Comparison of Modern Deep Learning Models for Toxicity Detection. In Proceedings of the 13th IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems, Gliwice, Poland, 4–6 September 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; Van Der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Podpora, M.; Baranowski, M.; Chopcian, M.; Kwasniewicz, L.; Radziewicz, W. LLM Firewall Using Validator Agent for Prevention Against Prompt Injection Attacks. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010085

Podpora M, Baranowski M, Chopcian M, Kwasniewicz L, Radziewicz W. LLM Firewall Using Validator Agent for Prevention Against Prompt Injection Attacks. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010085

Chicago/Turabian StylePodpora, Michal, Marek Baranowski, Maciej Chopcian, Lukasz Kwasniewicz, and Wojciech Radziewicz. 2026. "LLM Firewall Using Validator Agent for Prevention Against Prompt Injection Attacks" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010085

APA StylePodpora, M., Baranowski, M., Chopcian, M., Kwasniewicz, L., & Radziewicz, W. (2026). LLM Firewall Using Validator Agent for Prevention Against Prompt Injection Attacks. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010085