1. Introduction

Urban mobility in Lisbon faces growing challenges due to rapid urbanisation, increasing ride demand and environmental concerns. Lisbon, the capital city of Portugal, is a natural example of these challenges. In recent years, it registered a steep increase in usage of ride-hailing services (like Uber and Bolt), which, although created to improve efficiency, also worsened road congestion and price surges, reducing the global efficiency of the system [

1]. At the same time, the city maintains a strong dependence on private vehicle use, with around 390,000 vehicles entering and leaving the city each day, further contributing to traffic, parking scarcity and polluting emissions. This number, which exceeds 20,000 when compared to 2007, reflects the preference for private transportation in areas with limited public options [

2,

3].

With more than 550,000 inhabitants and approximately 2.8 million residents across its metropolitan area, Lisbon represents one of the densest and fastest-growing European capitals. Transport accounts for nearly 40% of local CO

2 emissions, making mobility a critical challenge in achieving climate neutrality targets. Lisbon has committed to a 60% emission reduction by 2030 under the MOVE Lisboa 2030 strategy [

4]. This combination of urban scale, institutional ambition, and advanced digital governance platforms makes Lisbon an ideal testbed for Shared Autonomous Vehicles (SAVs) and other innovative mobility solutions.

The public transport system in Lisbon, with a ring-radial configuration centred around the urban nucleus, facilitates access to the centre of the city, though hindering transportation between peripheral zones. Trips between Cascais and Loures or Vila Franca and Mafra, for example, need to go through the city centre, resulting in longer and more indirect routes.

Despite major efforts—like integrated pricing, combined transport passes, or the MOVE Lisboa 2030 improvements—movement across east–west routes remains weak. What is lacking is not additional vehicles; instead, seamless coordination and joint management along flexible designs that connect different transit forms are needed.

Recent city traffic studies show clear numbers behind these access issues. Data from the Instituto da Mobilidade e dos Transportes (IMT) show that about 390,000 personal cars move into or out of Lisbon daily [

2], demonstrating how much people still rely on their own vehicles. In addition, driving makes up close to 60% of all journeys across the Lisbon metro region, while buses and trains cover 16% [

5]. Because of this gap, the existing ring-and-spoke layout struggles—though it works well for trips going towards or from the centre, it fails when people need to go between outer areas, forcing them onto slower, roundabout paths.

SAVs might help address part of this issue. By using adaptable vehicle groups, gaps in low-traffic routes can be filled—this reduces commuting duration while lowering dependence on personal vehicles. Traffic eases, emissions drop and air quality improves. This aligns with Lisbon’s environmental goals, especially when combining it with electrification [

6].

Yet the true potential lies further down—where automated transport connects with collective access through managed information. Vehicles communicate nonstop: from vehicle to vehicle, vehicle to network, vehicle to service hub. For this to function well, oversight must be precise, data exchange transparent, and components closely linked. Urban areas able to align these elements—on technical and policy levels—are best positioned to achieve the effective operation of self-driving shuttles.

1.1. Context and Motivation

The continuous evolution of self-driving technologies and shared mobility has intensified the need for urban systems capable of integrating automation and sustainability. Lisbon, similarly to many other European capitals, faces a double challenge: reducing private vehicle dependency while simultaneously ensuring accessibility and equity in transport services. Although nowadays, ticketing systems and other initiatives from the MOVE Lisbon 2030 [

4] have already been implemented, the city still suffers from limited cross-peripheral accessibility. These conditions justify the exploration of emerging shared autonomous systems as a complementary plan to public transportation, reinforcing efficiency and connectivity throughout the entire metropolitan area.

At the same time, Lisbon’s proactive digital transformation—through initiatives like EMEL’s Open Data Platform and smart mobility dashboards—illustrates a favourable governance ecosystem for testing advanced mobility models. The combination of strong institutional structures (CML, AML, TML), ongoing decarbonisation policies, and data infrastructure readiness places Lisbon at the intersection of policy innovation and technological feasibility, making it an exemplary case for evaluating how Shared Autonomous Vehicles can be embedded within complex European governance contexts.

1.2. Problem Definition and Research Objectives

Although some international studies have explored SAVs, few have their focus centred on their adaptation to European cities of medium dimension and complex governing systems, as is the case of Lisbon. Most models and existing SAV structures are technically comprehensive but contextually narrow, frequently neglecting local policy alignment, infrastructural readiness and user acceptance [

7,

8].

Despite the rapid global expansion of simulation and service design models for SAVs (e.g., Vosooghi et al. [

8], Narayanan et al. [

9]), there remains a clear research gap: existing frameworks rarely integrate governance coordination with data interoperability. This fragmentation limits their applicability in real-world deployments, where institutional cooperation, information sharing, and public trust are equally decisive as technical optimisation. The absence of such integrative frameworks in medium-sized European cities highlights the need for models capable of linking governance, technology, and user-centred design within a single reference architecture.

To bridge this gap, the present work proposes a validated reference model for implementing SAVs in Lisbon, following the Design Science Research Methodology (DSRM) [

10,

11]. This study combines a Multivocal Literature Review, enterprise architectural modelling in ArchiMate, and empirical validation through expert and user feedback. The resulting artefact establishes a bridge between strategic policy and an applicable system architecture, ensuring technical and contextual relevance.

The research aims to contribute a structured model that articulates governance coordination, digital security mechanisms, and technological adaptability (through Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X)) to support the strategy of smart and sustainable mobility.

Although there has been consistent advancement in simulation work along with MaaS integration setups, current scholarship misses a model linking policy oversight and seamless data exchange while incorporating DSRM cohesively. Present methods tend to concentrate on just one or two aspects—these policy designs lack technological detail, whereas simulated systems often ignore real-world organisational contexts.

This paper fills the identified void. To the best of our knowledge, no existing SAV deployment model explicitly integrates governance coordination, data interoperability mechanisms, and a DSRM-based architectural design tailored to medium-sized European cities. It presents the initial functional framework integrating these three aspects tailored to a mid-sized European urban context—Lisbon. Through combining governance principles, flexible data architecture, or the step-by-step nature of DSRM within one construct, the project shifts from theoretical frameworks towards an approach logically sound yet practical for organisational use.

1.3. Structure of the Paper

This paper progresses in a linear fashion.

Section 2 reviews previous work on Shared Autonomous Vehicles, pointing out gaps and ongoing debates. In contrast,

Section 3 outlines the approach and reasoning behind the study. Meanwhile,

Section 4 develops the Lisbon Reference Model. Finally,

Section 5 assesses its performance through testing and verification.

Section 6 looks beyond the figures, examining structural, human, and technical factors that influence real-world operation. To conclude,

Section 7 emphasises key insights, gaps, and potential directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

The literature review methodology followed a Multivocal Literature Review approach, intending to gather the most recent and relevant knowledge regarding SAVs. Unlike traditional systematic reviews, an MLR incorporates both academic literature and grey literature, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon. The review process followed three phases—planning, conducting, and reporting—which are summarised in this section.

For this paper, the review results are reorganised along three thematic axes derived from the MLR findings: (1) SAV deployment frameworks and simulation; (2) urban governance and Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) integration; and (3) the use of Design Science Research in mobility contexts. This structure allows connecting theoretical, technical, and institutional perspectives relevant to the deployment of Shared Autonomous Vehicles in Lisbon.

2.1. SAV Deployment Framework and Simulation

Shared Autonomous Vehicles appear in the literature as a promising evolution of mobility systems, combining automation and shared use to reduce private vehicle ownership, increase vehicle utilisation, and complement public transport networks [

6]. Simulation studies consistently highlight that the impacts of SAV systems depend heavily on behavioural assumptions, service design, and urban form.

Rather than providing uniform performance values, the literature reports a wide range of outcomes across contexts. For instance, Hamadneh and Esztergár-Kiss document travel-time reductions between 13% and 42%, depending on traveller type [

12], while Fagnant and Kockelman estimate that Shared Autonomous Vehicles can reduce energy use by 12% and GHG emissions by 5.6% per vehicle [

13].

Studies focusing on fleet performance have shown that SAVs can generate significant operational efficiencies: in an agent-based modelling scenario, a single SAV was found to replace approximately 11 conventional vehicles albeit with an increase of around 10% additional vehicle-kilometres due to empty repositioning [

13].

Fagnant and Kockelman and Milakis and Seibert emphasise that the success of these systems depends not only on vehicle automation but also on policy coordination, data exchange, and behavioural acceptance. Empirical research shows that social–demographic determinants (age, gender, income), safety concerns, and cost remain decisive factors in user adoption. In parallel, technological barriers—such as infrastructure readiness, connectivity, and regulation—shape the pace of deployment [

10].

Accessibility-related studies also show potential improvements when SAVs or automated demand-responsive vehicles substitute conventional services. Dianin et al. report 13–17% increases in collective accessibility for peripheral areas under AV-based demand-responsive transport scenarios [

14], providing relevant insights for Lisbon’s inter-municipal mobility challenges.

To clarify the divergent outcomes documented in SAV simulation studies,

Table 1 synthesises key conclusions and highlights the methodological assumptions that drive these variations across urban contexts.

Across these studies, a recurring limitation is their technocentric focus: frameworks primarily model vehicle behaviour and demand response while overlooking the governance and data-sharing structures required for real-world operation. As illustrated by the variability of outcomes in

Table 1, performance results are highly sensitive to modelling assumptions and context. This reinforces the need for integrative models that link simulation insights to institutional coordination and interoperability architectures—precisely the gap addressed by this paper.

2.2. Urban Governance and MaaS Integration

Rolling out driverless transport involves more than cars or software—it changes how urban areas manage travel. Shared automated vehicles exist in a grey zone, part public oversight and partly run by private firms, requiring cooperation across layers—local government, regional transit bodies, service providers, technology suppliers; everyone needs to align. In Lisbon, this network features CML, AML, TML, and EMEL, each wielding some authority.

Studies repeatedly show that SAVs need full integration into wider MaaS setups. While Milakis and Seibert [

7] stress this, Carrese et al. [

15] add that disjointed governance weakens shared autonomous transport. In European cities, divided authority—local versus regional—delays progress. Missing open data standards or unclear legal frameworks further hinder rollout.

The studies reviewed in the MLR indicate that governance alignment is essential, acting as a central pivot. Well-defined policies on data access, service permits, or oversight maintain stability. For example, Lisbon’s MOVE Lisboa 2030 strategy moves towards such integration: public datasets [

16], electronic payments, and consistent pricing—which together offer a practical starting point for the SAV model developed here.

This idea shaped the system’s structure at both business and application levels. Where these tiers come together, public institutions work alongside private firms—sharing information, guiding choices, while ensuring responsibility.

2.3. Design Science Research in Mobility Contexts

The Design Science Research Methodology (DSRM), presented by Hevner et al. [

10] along with Peffers et al. [

11], has become widely used in practical research—this is where working solutions are built for complex, everyday environments. Within transport-related fields, its use is growing quickly, since it connects abstract ideas with real operating systems. Because of this trait, it is well suited for exploring innovations such as Shared Autonomous Vehicles (SAVs) or Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS).

Recent research in transportation, like that of Rosa et al. [

17], explains that DSRM supports ongoing updates to reference frameworks. With every test phase—such as workshops or user trials—the model improves gradually. This study follows a similar path: begin with an idea, evaluate it through expert input, then adjust it so that it works well in practice and aligns with theoretical principles.

The literature highlighted an additional helpful aspect: using enterprise architecture models, especially ArchiMate 3.2 [

18]. These are more than drawings—they show how complicated systems with multiple actors work together. Linking architectural planning with governance and operations makes strategies such as “MOVE Lisboa 2030” become real processes, technical rules, and connections between components.

This framework makes the Lisbon SAV model more than just a diagram—it acts as a functional tool capable of shaping choices, integrating with simulations, or evolving into numerical methods down the line. This point illustrates the connection between practical application and conceptual reasoning.

2.4. Conceptual Framework

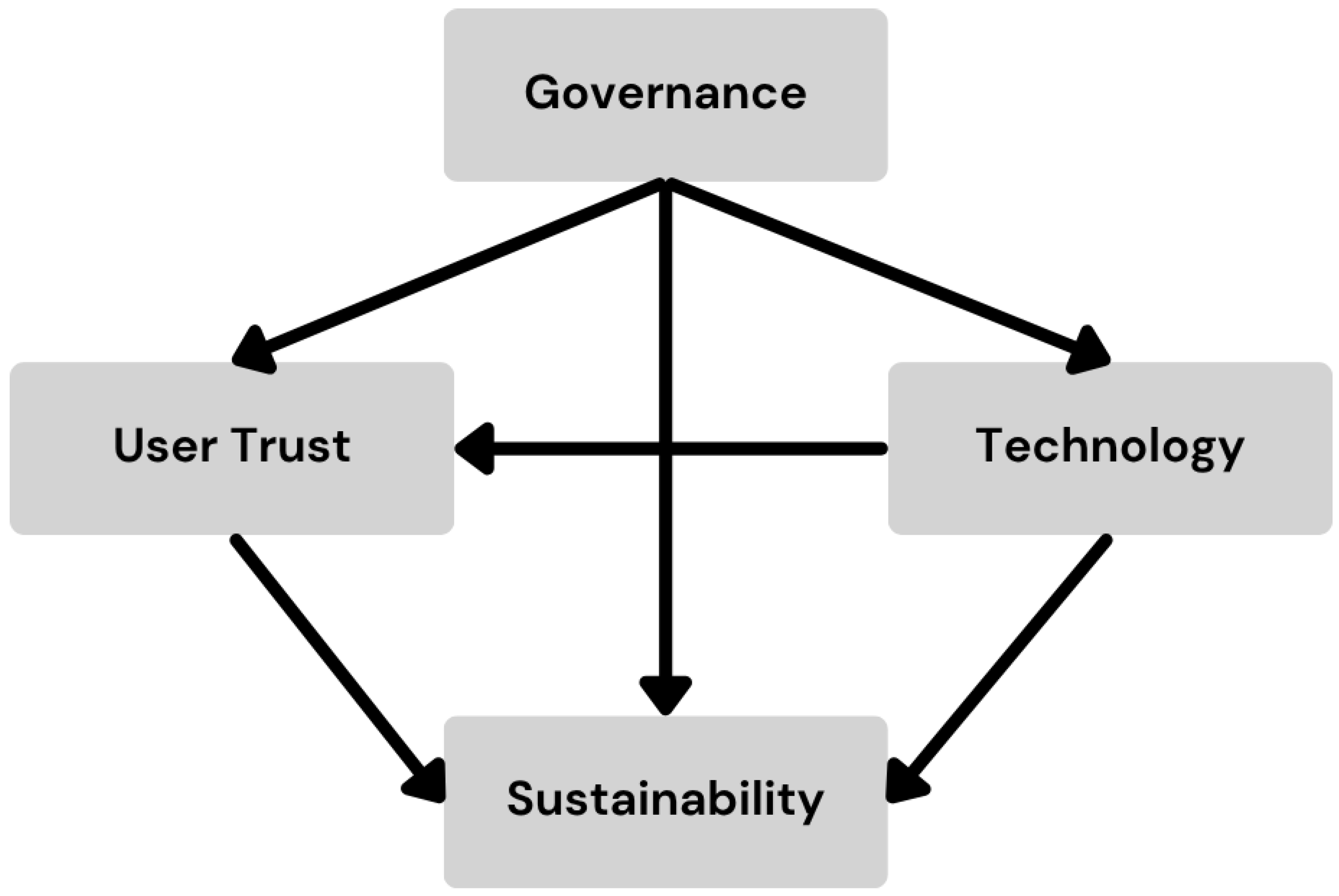

Out of the three main themes, a clear structure emerged—one designed to show what actually influences Shared Autonomous Vehicle (SAV) deployment. Four key aspects became visible: these are linked yet distinct, each playing an essential role:

Governance with policy alignment means coordinating different actors through consistent rules so they work together smoothly instead of at cross-purposes.

Technological readiness forms the core—infrastructure matters, along with internet access; smooth data exchange is essential.

User trust plus social acceptance—perception plays a key role here; survival hinges on safety, fairness, or actual utility.

Sustainability built in—so SAVs transport individuals while supporting emissions cuts or changes in travel habits.

As seen in

Figure 1, these contribute to what the research labels SAV Implementation Readiness. Each aspect influences it uniquely; however, combined, they measure a city’s progress towards actualising automation. This structure served as the foundation for Lisbon’s model, linking theoretical insights with practical local application and experimentation.

Overall, the research shows a consistent trend: digital tools by themselves cannot bring self-driving vehicles into everyday use. Instead, these systems require management structures suited to their intricacy along with public confidence. Models demonstrate potential benefits—like reduced travel time or lower pollution—but frequently overlook the organisational foundations needed for lasting success. On the other hand, policy efforts tend to define regulations while ignoring technical realities.

This paper connects the parts using Design Science Research. By doing so, it fills the void with a framework tailored to Lisbon—aware of governance, based on evidence, and also built to link up with simulations. The idea is not abstract; instead, it is practical and can function in real settings.

3. Methodology

This study followed the Design Science Research Methodology (DSRM) to design, develop, and evaluate an artefact capable of addressing a real-world problem—the deployment of SAVs in Lisbon. This methodological approach combines the theoretical grounding in previous works, artefact construction using ArchiMate, and empirical validation through semi-structured interviews, ensuring that the proposed model is both conceptually rigorous and contextually relevant [

10,

11]. In addition, a set of scenario-based performance indicators commonly used in the SAV literature was incorporated to support the interpretation of potential impacts in different deployment configurations.

3.1. Design Science Research Approach

The DSRM approach, as defined by Hevner et al. [

10] and Peffers et al. [

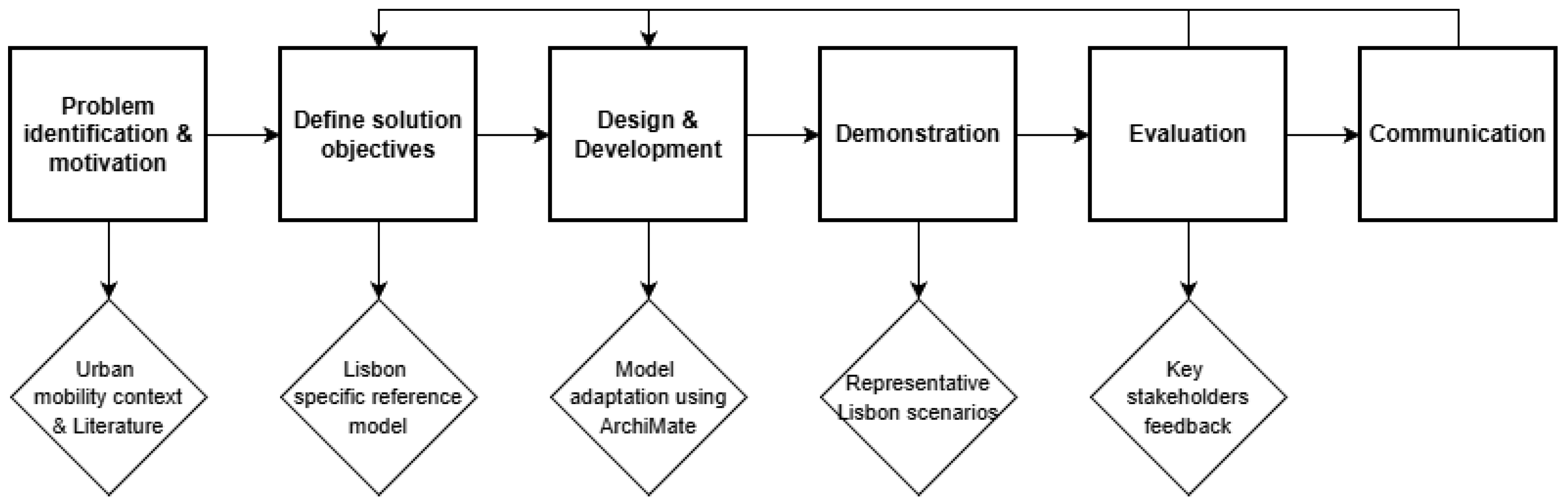

11], provides a rigorous methodological structure for the development and evaluation of artefacts that answer the previously identified organisational challenges. The process was applied following six sequential and interconnected steps. A DSRM flowchart is presented in

Figure 2, identifying the different phases and outputs, highlighting the iterative feedback loop through which evaluation results informed subsequent design refinements.

The first one corresponds to the identification of the problem and motivation, focusing on the inefficiencies present in Lisbon’s ring-radial public transport system and its strong dependence on private car usage. Following this is the definition of the solution objectives, aiming to conceive a reference model that represents the interrelations between actors, services, and technologies in a possible SAV system.

Posteriorly, the artefact was designed and developed using an enterprise modelling architecture in ArchiMate, which was subsequently demonstrated through its contextualisation within the Lisbon mobility ecosystem. The evaluation phase followed, allowing for the verification of the model’s conceptual coherence, viability, and perceived utility. Ultimately, the communication phase involved presenting and discussing the results in specific academic, professional, and real-life scenarios.

To complement this design cycle, scenario-based analysis was later supported through key performance indicators (KPIs) derived from existing SAV simulation studies, enabling an additional interpretation of the model’s potential operational effects.

3.2. Evaluation Strategy

The artefact was validated through a qualitative evaluation strategy, combining the phases of demonstration and validation, in conformity with the DSRM principles. The demonstration involved applying the model to Lisbon’s existing mobility system to assess its suitability for the city’s governance structures, transportation networks, and digital infrastructure.

The evaluation involved semi-structured interviews conducted with 21 participants who were divided into two groups. The first group consisted of eleven experts from various entities related to transportation, including both public and private sectors, such as the Câmara Municipal de Lisboa (CML), Carris, Metro de Lisboa, and Volkswagen Group, among others. This group analysed the governing structure, integration potential and the strategic alignment of the model. The remaining interviewees consisted of 10 end-users, all residents of Lisbon, with ages ranging from 18 to 62 years, who evaluated the security and trust perceptions, usability, and economic accessibility.

The data were analysed following a reflexive thematic analysis, following the framework based on Braun and Clarke [

19]. Initial codes were developed from the participants’ answers, which were then organised into themes that reflected both convergences and divergences in opinions between the two groups. This process confirmed the models’ internal coherence, contextual realism, and social relevance, ensuring that the evaluation results were simultaneously empirically grounded and consistent from a theoretical perspective.

This qualitative validation was later complemented by scenario considerations using the performance indicators described in

Section 3.3.

3.3. Modelling Tools, Data Sources and Scenario-Based KPIs

The reference model was developed using the Archi tool (version 3.2), which is an open-source modelling platform compatible with ArchiMate 3.1 standard [

18]. Archi was used to visually create and organise the model into its three layers (business, application, and technology), keeping a consistent notation and aligned with standard conventions.

All modelling work was grounded in the 34 validated components present in the original reference model proposed by Pereira et al. [

20]. The original components were revised, adapted or maintained in accordance with their relevance for the Lisbon context. The instantiation of the model was grounded in both academic literature and professional reports concerning mobility, public transport and smart city initiatives.

The process was conducted manually, following an iterative design approach, which was supported by document analysis and thematic clustering [

21]. No simulation software, statistical tools or programming frameworks were applied, as the focus was exclusively on the conceptual architecture and logical structure of the SAV system. This aspect reinforces the conceptual character of the artefact, positioning it as a visual and analytical framework rather than a computational tool [

19]. The final artefact was then exported in image format and constitutes the primary demonstrational instrument of this article.

To support the scenario analysis introduced in

Section 5, performance indicators commonly used in SAV research were incorporated into the methodological design as interpretive and design-guiding references rather than as quantitative outputs of this study. These indicators, present in

Table 2, informed the selection and structuring of components across the reference model, ensuring that the artefact could be consistently interpreted using metrics widely adopted in the literature while preserving its qualitative and conceptual nature. These are outlined in the table below.

These KPIs do not replace qualitative validation; rather, they complement it by allowing the reference model to be interpreted through indicators commonly used in the SAV literature.

4. Model Development

The artefact developed in this study is based on the validated reference model proposed by Pereira et al. [

20], which was tested initially in international contexts, like with Waymo in Phoenix and Baidu Apollo in Beijing [

17,

22]. This prior framework served as a structural basis for the representation of SAVs in urban environments, integrating business, application and technology dimensions using an enterprise architecture.

For this paper, the original model was adapted, refined, and instantiated to the specific institutional, infrastructural, and operational conditions of Lisbon. This process involved identifying which components of the foundational artefact could be directly transferred, which required modification, and which new components needed to be added to accommodate the governance, data, and mobility characteristics unique to Lisbon.

The adaptation was supported by Lisbon’s mobility strategies, such as MOVE Lisboa 2030, and the digital infrastructure ecosystem, including EMEL’s open data platforms. Together, these sources enabled a contextualised interpretation of the original model, ensuring that it remained coherent with the city’s current and planned mobility evolution.

4.1. Reference Model as Foundation

The reference model proposed by Pereira et al. [

20] served as the primary foundation for this research. This original artefact was composed of 34 validated components, which were organised across business, application, and technology layers. The model had previously demonstrated its relevance and completeness in multiple use cases, which facilitated the identification of essential elements for SAV operations and the relationships between them.

In transferring this model to Lisbon, each component was reviewed individually to assess its fit within the city’s governance structure (CML, AML, TML), its public transport network (Carris, Metro de Lisboa), and its digital ecosystem (EMEL open data, multimodal platforms). Components that lacked contextual alignment were adapted, merged, or removed, while new ones were introduced to represent Lisbon-specific institutional mechanisms, data flows, and service integration requirements.

Critically, specific model components were introduced to address Lisbon’s unique contextual constraints. For instance, the fragmentation between municipal (CML) and metropolitan (TML) competencies necessitated the addition of an `Inter-institutional Coordination’ component in the business layer to formalise joint oversight. Similarly, the `poor cross-peripheral connectivity’ identified in the diagnosis drove the design of the `Demand-Responsive Routing’ module in the application layer, ensuring the system prioritises underserved orbital routes over well-served radial ones.

This process resulted in a refined architecture that maintains its conceptual foundation while reflecting the Lisbon mobility ecosystem in a realistic and operationally meaningful way.

4.2. Instantiation Methodology

The instantiation methodology followed an enterprise architecture modelling approach using the Archi tool (version 3.2), which is compatible with the ArchiMate 3.2 specification. ArchiMate was selected because it provides end-to-end traceability across business, application, and technology layers, which is essential for modelling the interdependencies of SAV systems. Unlike BPMN, which focuses primarily on process flow, or UML, which emphasises software-level design, ArchiMate enables the representation of governance structures, service interactions, data flows, and technological assets within a unified notation. This makes it particularly suitable for complex socio-technical systems such as SAV mobility architectures.

All modelling steps were grounded in document analysis, thematic synthesis, and the results of the Multivocal Literature Review. The process also incorporated insights from the empirical evaluation phase, which provided valuable feedback regarding governance clarity, user trust, and technological requirements.

Additionally, the instantiation was guided by the performance indicators presented in

Section 3, which helped clarify the links between model components and the expected impacts on travel time, emission reduction, fleet utilisation, and service coverage. These links ensure that the artefact is not only descriptive but also operationally interpretable through measurable outcomes.

The resulting model, therefore, provides both a conceptual representation and an evaluative structure capable of supporting scenario-based assessments.

4.3. Overview of the Model

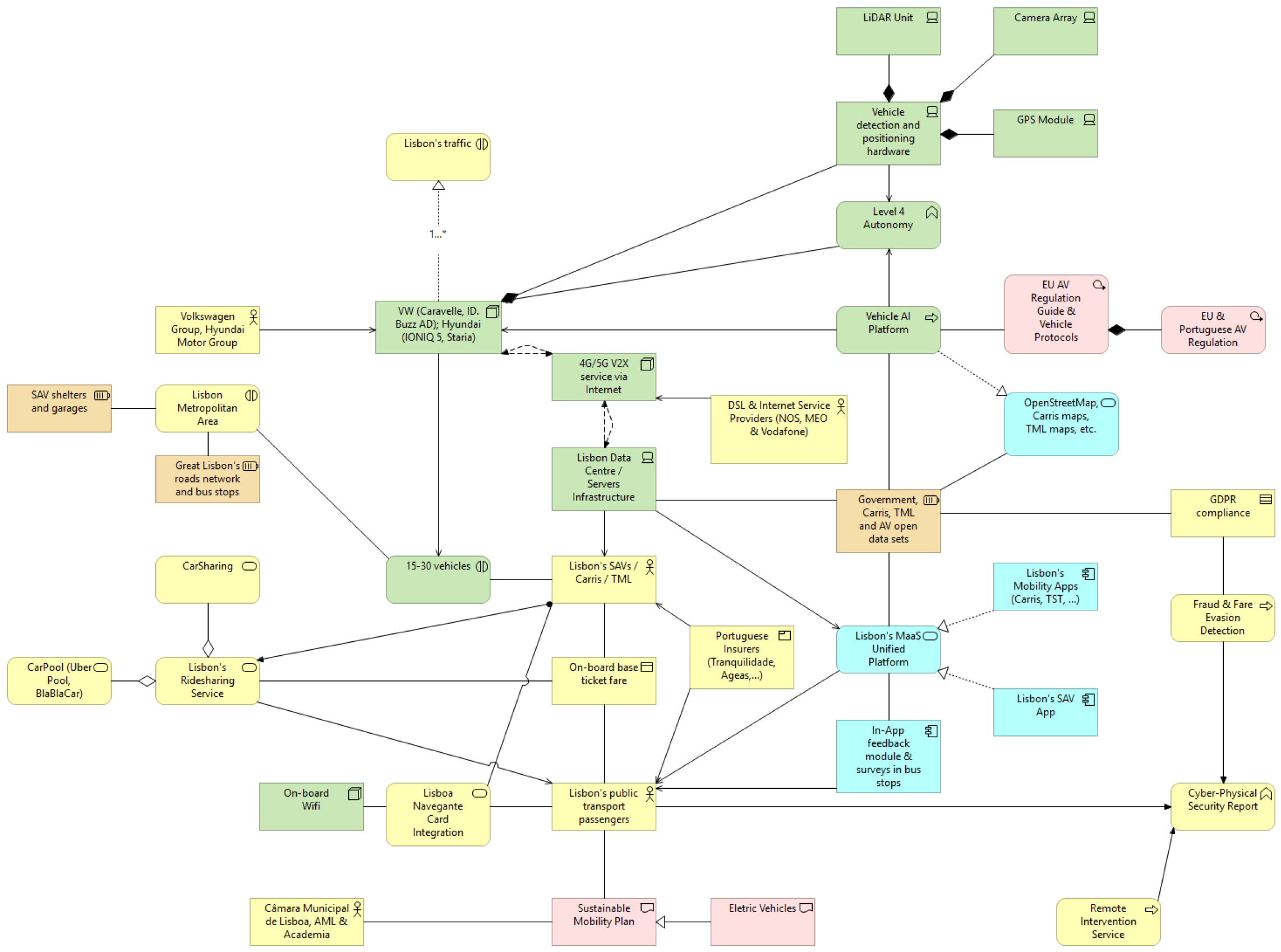

The resulting artefact is composed of three main layers—business, application and technology—supported by strategy and implementation elements, as seen in

Figure 3. Each layer describes the fundamental components, relationships, and information flows that make the SAV system function possible.

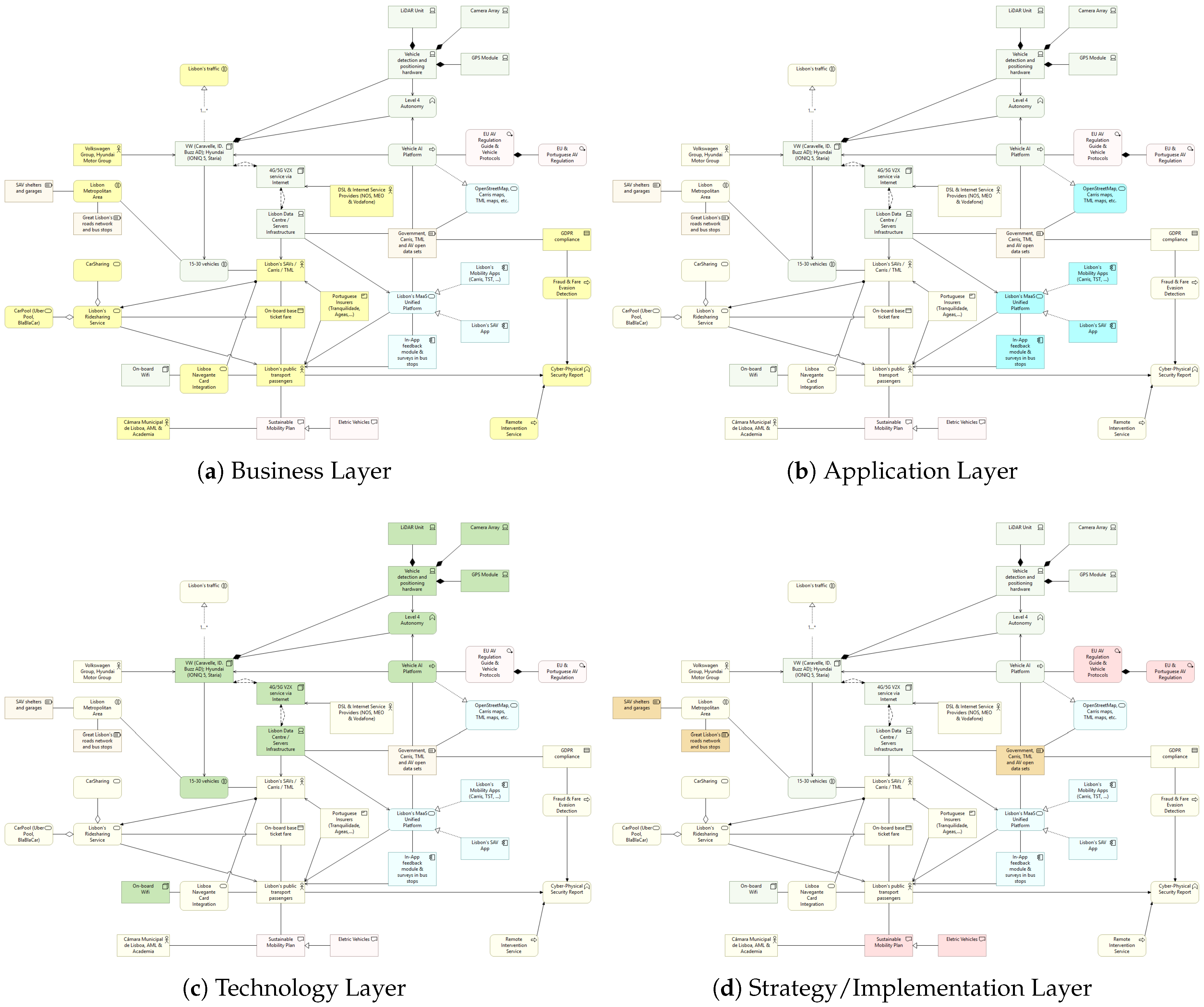

Business Layer. The business layer (

Figure 4a) defines key institutions and organisations involved in decisions, services, and oversight in Lisbon’s transport network. Public authorities like CML, AML, and TML hold regulatory, planning, and coordination responsibilities at city and regional scales. Operators such as Carris appear in this level due to their role in delivering public transit under a unified framework. Private companies, like Volkswagen and Hyundai Group, belong in the business layer since their operations extend beyond manufacturing—they manage fleet operations, run platforms, and form alliances with government bodies. Passengers using public transit count as business stakeholders because their choices affect whether services succeed or fail. Internet connectivity providers (DSL and satellite) are also placed in this layer, as they act as external service enablers governed by contractual and regulatory arrangements. The services shown—Ridesharing, CarPool, CarSharing, along with Lisboa Navegante Card Integration—are direct mobility offerings for users, so they sit at the business layer. Operational processes such as Fraud and Fare Evasion Detection and the Remote Intervention Service ensure compliance and safety, while the Cyber-Physical Security Report function captures institutional obligations related to accountability and incident reporting.

Application Layer. The application layer (

Figure 4b) comprises the digital systems that orchestrate interactions between users, operators, and services. The Lisbon MaaS Unified Platform is positioned as a central application component because it integrates booking, routing, and payment functionalities across multiple providers. Supporting modules such as In-App Feedback Systems enable user–operator communication and service monitoring, while mapping and routing interfaces (e.g., OpenStreetMap and Google Maps) are included as application components due to their role in providing navigational logic and decision support rather than direct vehicle control.

Technology Layer. The technology layer (

Figure 4c) encompasses the physical and computational infrastructure enabling autonomous operation. This includes vehicle sensors and perception devices (LiDAR, cameras, GPS), V2X communication supported by 4G/5G networks, and onboard connectivity systems. These components directly support real-time perception, coordination, and safety. The Lisbon Data Centre is included as the hosting and data-management backbone for system operation, while vehicles are modelled as SAE Level 4 autonomous units [

23], operating in coordinated corridors of 15–30 vehicles. This representation reflects assumptions regarding fleet-level optimisation and collective vehicle behaviour.

Strategy and Implementation. Strategy and implementation elements (

Figure 4d) capture long-term enablers and constraints shaping deployment. These include SAV depots, charging infrastructure, open data resources, and compliance with European and Portuguese autonomous vehicle regulations. Together, they ensure alignment with Lisbon’s strategic objectives for sustainable, integrated, and digitally enabled mobility [

4].

The artefact explicitly connects conceptual, digital, and operational domains through relations of serving, realisation, assignment, and composition. This ensures complete traceability between governance, service and the technology layer, allowing the model to act as a planning and analytical tool for future SAV implementation.

To simplify visual communication, the updated artefact is represented in one consolidated architecture figure (

Figure 3), where each layer is depicted with a distinct colour (

Figure 4) and connected through serving, assignment, and realisation relations.

The model was further connected to the KPIs presented in

Section 3, allowing the following relationships:

Governance and business layer: service coverage, coordination quality;

Application layer: user trust, system reliability, satisfaction;

Technology layer: travel time reduction, emission reduction, fleet utilisation.

This mapping ensures that the artefact is aligned with both Lisbon’s mobility policy goals and the performance dimensions commonly analysed in SAV research.

5. Demonstration

This section demonstrates the application of the proposed reference model in the Lisbon context, evidencing how the artefact can operate under real-world conditions and evaluating its contextual viability. In line with the principles of the DSRM, this stage corresponds to when the artefact is applied to assess its fit within the city’s operational and institutional framework [

10,

11]. The scenarios are interpreted using only performance indicators explicitly quantified in existing literature, ensuring a rigorous and traceable interpretation of potential system impacts.

5.1. Lisbon’s Urban Mobility Context

Lisbon’s residents still maintain a strong dependency on the private car, with approximately 60% of all trips made in the metropolitan area being by car, in contrast to around 16% being made with public transport [

5]. This imbalance results from the public transport structure, which was conceived to connect the peripheral areas to the centre, being efficient in centripetal journeys but offering limited opportunities for cross-peripheral connections. Approximately 390,000 vehicles enter or exit Lisbon daily, contributing significantly to urban pressure and emissions [

2,

3].

Efforts such as MOVE Lisboa 2030 aim to strengthen modal integration, accessibility, and sustainability. Within this context, SAVs constitute a complementary strategy capable of addressing network gaps and enhancing the flexibility of multimodal mobility particularly in peripheral or temporal niches underserved by conventional public transport.

5.2. Scenario Definitions and Technological Fit

To explore potential outcomes, three scenarios were developed: a simple base case, an intermediate version with limited automation, and a final case that reflects full integration guided by MaaS concepts. Each builds on confirmed data from published research and key mobility assessments rather than guesses. All scenario interpretations rely exclusively on performance indicators documented in peer-reviewed literature and do not represent the simulation results produced by this study.

Scenario A—Status Quo (Baseline). This scenario maintains the status quo. Without Shared Autonomous Vehicles (SAVs) or system integration, the present network runs unchanged. The setup continues exactly as it functions today.

Scenario B—Partial SAV Integration. SAVs cover gaps in transport networks by handling brief journeys—like initial and final legs of travel, overnight routes, or remote areas. Connections to MaaS tools and shared data infrastructures are present yet narrow. While these vehicles support accessibility, integration remains partial and uneven across regions. Evidence from autonomous-mobility simulations suggests that substantial travel-time reductions may arise when AVs replace indirect or multimodal trips. Hamadneh and Esztergár-Kiss [

12] report individual travel-time reductions ranging from 13% to 42%, including 33% reductions for former public-transport riders and 16–28% for other groups [

12]. In Scenario B, such values guide the interpretation of how SAVs could shorten trips on Lisbon’s most indirect corridors (e.g., inter-peripheral travel that currently requires centre-bound detours).

Scenario C—Full Integration with MaaS and Public Transport. This version presumes full coordination—SAVs along with public transit, payment setups including Navegante card, or data-exchange centres like EMEL’s system operating together. Environmental and fleet-level implications can be interpreted using documented findings from shared-autonomy studies. Fagnant and Kockelman [

13] estimate that SAVs can reduce total energy use by 12% and GHG emissions by 5.6% per vehicle relative to average light-duty vehicles. At the fleet level, their agent-based modelling suggests that one SAV can replace approximately 11 conventional vehicles albeit with around 10% additional vehicle-kilometres due to empty repositioning [

13]. Accessibility studies also point to measurable improvements when automated, demand-responsive vehicles substitute fixed-route services. Dianin et al. [

14] report 13–17% increases in collective accessibility for peripheral areas under AV-based scenarios [

14], which provides a relevant proxy for Lisbon’s inter-municipal mobility challenges.

Together, these documented indicators help interpret Scenario C as one where integrated SAV fleets could generate measurable benefits in travel times, energy use, emissions, and peripheral accessibility contingent upon coordinated governance and digital interoperability.

5.3. Service Scenarios

To better illustrate the applicability of this service, three hypothetical service scenarios were developed, demonstrating how SAV operations could support the city’s mobility goals:

Periphery-to-periphery connections: This scenario illustrated how SAVs could provide direct, demand-responsive services between outer municipalities (e.g., Amadora–Loures), reducing dependency on the city centre and alleviating traffic through the main urban arteries.

Night and off-peak service: A flexible, shared service connecting nightlife areas and residential zones between 1 a.m. and 6 a.m., improving accessibility and safety during periods of low public transport frequency.

Integrated payment and multimodal experience: The inclusion of the Lisboa Navegante Card as a unified digital ticketing and payment tool, allowing seamless transfers between SAVs, buses, and metro services.

These service structures align with the conceptual roles of SAVs identified in the reference model.

The strict travel-time reductions (13–42%) reported by Hamadneh and Esztergár-Kiss [

12] support the expectation that direct, on-demand inter-peripheral connections could meaningfully lower route durations for affected corridors.

5.4. Differential Scenarios for Local Climate and Demographic Needs

To complement the baseline and integration scenarios, differential scenarios were developed to reflect operational conditions specific to Lisbon’s climate and demographic distribution.

Climate stress scenario (extreme heat and rain): During summer heatwaves exceeding 35 °C or periods of intense rainfall, SAV operations require enhanced cooling loads, adapted routing for flooded streets, and increased safety monitoring. These factors may temporarily reduce fleet efficiency or increase energy consumption while reinforcing the need for resilient V2X communication and weather-aware routing algorithms.

Tourism-intensification scenario: Seasonal influxes exceeding three million annual visitors produce demand peaks in Baixa, Belém, and Parque das Nações. SAV deployment under this scenario prioritises dynamic fleet resizing, multilingual safety interfaces, and integration with tourism-oriented mobility services.

Demographic sensitivity scenario: Older adults and late-night users reported distinct safety and accessibility concerns during interviews. The SAV design under this scenario integrates real-time monitoring, in-vehicle emergency systems, and micro-fleet services supporting off-peak hour mobility.

These differential scenarios demonstrate how SAV deployment must be adapted to climatic, temporal, and demographic variations, extending the applicability of the reference model to real-world constraints.

5.5. Observations and Expected Outcomes

The scenario approach shows how the suggested framework might practically support adding Shared Autonomous Vehicles (SAVs) to Lisbon’s transit system. Although no direct simulations were conducted here, each case relies fully on confirmed data from existing reports that were chosen intentionally to base findings on observable facts. Such measures link engineering plans more closely to actual management and field requirements.

In terms of movement efficiency, the results align well with earlier studies on self-driving transit. According to Hamadneh and Esztergár-Kiss, the time saved varied between 13% and 42%, standing at roughly one third for those switching from buses or trains, while others saw gains of 16% to 28% [

12]. Applying these data to Lisbon implies that immediate SAV access might drastically cut travel duration across outer districts now reliant on routes going through the city core.

Environmental alongside operational figures show comparable trends. According to Fagnant and Kockelman, each SAV may reduce overall energy consumption by 12% while cutting greenhouse gases by 5.6% when set against standard light-duty cars [

13]. When applied to Lisbon’s setting, this suggests advantages for electric, shared vehicles—particularly if linked with existing transit systems instead of undermining them. Their analysis further indicates a single SAV might substitute around eleven traditional automobiles; however, it could add nearly 10% extra vehicle-kilometres due to empty repositioning moves. This aspect is particularly significant: without solid coordination together with smart routing, potential efficiencies risk being lost.

In terms of accessibility, research by Dianin et al. indicates a 13–17% gain in shared mobility reach across outlying regions when using self-regulating, request-based networks [

14]. In Lisbon’s suburban belt—locations such as Loures, Odivelas, or Almada—this level of progress might reduce the current divide between fringe zones and central city services.

From a management perspective, the situations clearly show that launching SAVs cannot fall on just one agency. CML, AML, TML, and EMEL, along with current public providers, all control pieces of the network. The framework’s business layer maps how these parts interact, whereas the application layer defines data movement, tracking, and technical links needed for collaboration. For users, confidence, clear safety checks, and cost matter most. Tools like safety displays, integrated pricing, and fast support lines constitute essential system components rather than optional additions.

The combined evidence and model design suggest Lisbon already has foundational elements in place. Instead of beginning anew, existing frameworks provide a basis for progress. This framework introduces organisation—showing how institutions, tech systems, and oversight might align. Rather than remaining abstract, the scenarios tie this outlook to real-world data, offering officials practical support when shaping initial strategies.

5.6. Robustness Check of Scenario Interpretations

To reinforce the internal validity of the scenario interpretations, a qualitative robustness check was conducted using a range of performance indicators reported in peer-reviewed SAV studies.

Table 3 summarises the variation intervals drawn from the literature and the corresponding implications for the Lisbon context.

The robustness check indicates that the qualitative conclusions of Scenarios B and C remain stable even when considering conservative KPI values. The highest sensitivity is associated with vehicle-kilometres travelled (VKTs), highlighting the importance of governance coordination and real-time optimisation in reducing empty repositioning.

5.7. Illustrative Lisbon-Specific Scenario Projections

To complement the literature-based scenario interpretation, a set of illustrative Lisbon-specific projections was developed. These values do not constitute transport-model outputs; they apply documented relationships from European assessments to publicly available mobility data for Lisbon.

For the empirical basis, three external datasets were used:

The Instituto da Mobilidade e dos Transportes (IMT) reports that approximately 390,000 private vehicles enter or leave Lisbon each day [

2,

3].

The UPPER EU Project and the POLIS Network indicate that car travel accounts for around 60% of trips in the metropolitan area [

5].

The European Environment Agency (EEA) shows that shifting 3.5% of urban trips to shared autonomous vehicles can reduce GHG emissions by approximately 5.6% [

24].

Based on these values, two uptake ranges were created to reflect how varying SAV usage could alter Lisbon’s current travel patterns. In Case B, SAVs are expected to take over around 1–2% of everyday vehicle inflows; applying this to IMT data results in approximately 3900 to 7800 individual car journeys being substituted each day. In Scenario C, uptake is projected at 3.5–5% based on the EEA’s 3.5% benchmark—this equals roughly 13,650 to 19,500 car trips per day.

Estimating environmental effects requires an equally transparent method. According to EEA data, a 3.5% SAV share leads to a 5.6% fall in GHG—this means each 1% rise in SAV use cuts emissions by roughly 1.6%. While scaling assumptions stay fixed, the ratio remains stable across estimates. Since patterns do not shift drastically, applying uniform rules helps maintain clarity without distortion.

That ratio leads to a drop of 1.6–3.2% in Scenario B, while in Scenario C, the decrease ranges from 5.6 to 8.0%. Although results differ across cases, the trend remains consistent. Each scenario shows lower values when applying the method. Changes are modest but noticeable under both conditions.

The resulting values are summarised in

Table 4 and should be interpreted strictly as contextual illustrations of magnitude rather than as forecasts. They do not account for routing patterns, induced demand, empty-vehicle kilometres, or multimodal interactions, all of which would require a calibrated transport simulation. Their purpose is therefore limited to grounding the scenario demonstration in publicly verifiable data while preserving methodological transparency.

Linear scaling is used here solely as a first-order proportional estimate, consistent with the EEA’s methodological interpretation framework, and not as a predictive model of Lisbon’s emission dynamics.

6. Evaluation

This section presents the evaluation phase of the research in relation to the DSRM. The purpose of this phase is to verify the applicability, coherence, and perceived value of the proposed reference model for SAVs in Lisbon.

The integration of documented performance metrics from existing SAV simulation studies, combined with governance and technological considerations emerging from expert feedback, strengthens the model as both a conceptual artefact and a practical decision-support structure.

6.1. Comparison with International Experiences

Several international deployments offer relevant comparison points for interpreting Lisbon’s potential SAV evolution. International SAV deployments provide valuable insights for interpreting Lisbon’s potential trajectories.

Phoenix. Waymo has operated Level 4 autonomous ride-hailing services in Phoenix for several years [

17]. Its deployment relies on advanced mapping, continuous data-sharing, and remote support systems. Although the urban morphology of Phoenix differs significantly from Lisbon, its demonstrated capability to provide reliable, delay-reducing autonomous trips suggests that similar routing improvements could be achievable where governance and digital infrastructures are aligned.

Singapore. Singapore was one of the first cities globally to authorise public-road AV pilots under tightly coordinated governance and unified digital mobility frameworks [

25,

26,

27]. As in Lisbon, governance synchronisation and integrated data platforms were critical enablers of successful early-stage deployment, highlighting the importance of unified institutional structures and real-time monitoring systems.

Stockholm. Stockholm tested self-driving minibuses in areas with few passengers, integrating them into existing transit routes [

28]. These experiments revealed a basic truth—automated vehicles perform better by filling missing links rather than copying strong systems. Instead of replacing buses on busy paths, they connected suburban zones to key hubs. By doing so, they improved reach without requiring heavy infrastructure investment. This trend reflects Lisbon’s situation. On its outskirts, access remains limited, whereas Stockholm suggests a possible fix: compact vehicle groups that connect digitally to central networks for coordination.

SAV performance depends less on tech alone but more on how different aspects work together—shared duties across agencies, connected digital platforms, and links to existing transport flows. These elements also define the Lisbon approach, turning field tests into practical tools for urban planning.

6.2. Governance, Interoperability and Organisational Implications

The evaluation underscored governance as a central factor in SAV feasibility. Institutions such as CML, AML, TML, Carris, and EMEL collectively shape the city’s mobility ecosystem. Their coordinated operation defines regulatory consistency, service integration, and system transparency.

The business layer of the reference model structures these interactions. The incorporation of interinstitutional coordination mechanisms directly responds to expert feedback, which highlighted fragmentation between municipal and metropolitan competencies as a major barrier to SAV implementation.

As one expert put it, “At this moment there is no regulation at all—everything depends on Europe creating directives, and only then can Portugal adapt them locally.” Another interviewee emphasised liability as a critical constraint: “If an accident happens, who is responsible? Until this is clarified, deployments will remain limited to controlled routes.” Users also mirrored this uncertainty, with one noting: “People would be very suspicious at first—especially older people. Many of my friends don’t even want to use ATMs, let alone a driverless vehicle.”

Interoperability was also emphasised. The application layer establishes how digital platforms interact through booking systems, routing engines, monitoring dashboards, and shared data infrastructures. This reflects not only Lisbon’s existing digital capabilities but also lessons from Singapore, where MaaS-like integration enabled centralised oversight and efficient service coordination [

27].

Safety, trust, and user perception were identified as core determinants of adoption. By integrating safety dashboards, remote monitoring functions, and reporting mechanisms, the reference model embeds the transparency and redundancy required to enhance public trust—a factor repeatedly emphasised in user interviews and SAV literature [

9].

One expert noted: “Integration with existing digital platforms is crucial; otherwise the service will fail to coordinate with the rest of the network.”

6.3. Qualitative Evaluation Findings

The qualitative assessment brought real-world context to the prototype test, looking beyond design to see how it could perform in daily life across Lisbon. Instead of focusing only on technical aspects, this phase explored practical functions in urban settings. A total of twenty-one guided conversations took place—eleven with staff from municipal, regional, and mobility agencies such as CML, AML, TML, Carris, and EMEL, along with private sector representatives; ten others involved locals between 18 and 62 years old. Rather than abstract analysis, the aim was clear: to understand potential challenges, benefits, and viability through the perspectives of future developers and users of Shared Autonomous Vehicles.

Table 5 summarises the frequency of occurrence of the main themes identified during the qualitative analysis, indicating how often each concern was raised across expert and end-user interviews and the corresponding implications for the refinement of the reference model.

Expert views focused on three main ideas. To begin with, clear governance was seen as essential—most agreed that government agencies need defined duties before rollout. Without this, overlapping powers could disrupt collaboration and block system integration. Next, attention shifted to how data are managed and protected, which is viewed by many as foundational. Since self-driving vehicles depend on steady exchanges between vehicle groups, transit systems, and mobility apps, poor safeguards or mismatched rules might trigger functional failures. Third, beginning on a smaller scale is essential. Some attendees supported test runs—like restricted routes or step-by-step experiments—since these help gain community confidence while allowing oversight bodies room to adjust prior to wider rollout. One expert emphasised this clearly: “Public communication is essential—only then will regulators and citizens accept the service.”

End-user talks introduced additional qualitative insights related to perceptions and personal experiences. In each discussion, security stood out as key. As one participant explained, “My biggest fear is the lack of a driver… especially at night, that could lead to risky situations between passengers.” Another user stated: “I would feel safer if there were cameras, an emergency button, and someone watching the trip in real time.” Even so, several participants expressed openness to trial: “In the beginning, I wouldn’t feel safe, but if I saw others using it and everything worked well, I would gain confidence.”

Pricing was mentioned frequently. Although people showed interest in using shared autonomous vehicles, they expected prices to remain near those of public transit or below typical car ownership costs. Some brought up a different concern—loss of jobs. Among older participants in particular, there was unease over how automation might affect society; therefore, they argued that policies ought to include support like retraining initiatives and help shift workers into new roles. One user summarised: “If it’s expensive, people like me simply won’t use it.” Others highlighted the need for reliable integration: “If it worked with the Navegante card, that would make everything much easier.”

These findings changed the framework noticeably—adjustments were made accordingly; improvements followed directly: (i) improved links across institutions became part of the business layer through better integration methods; (ii) safety dashboards, along with emergency alert setups, went into the application layer; tools letting users submit reports were also included; and (iii) the Technology Level now covers distant oversight and security measures against digital threats while also integrating live tracking centres.

These changes combined made the model more practical, linking it to real-world use. Testing showed SAV deployment involves shared responsibility shaped by clear rules and public confidence, rather than tech alone.

6.4. Technical and Performance Implications

The technology layer synthesises the technological requirements for SAV deployment, including autonomous sensing suites, V2X communication, charging infrastructure, security layers, and data centres.

The case study from

Section 5 links every part of the setup to actual recorded outcomes through structured examination. Travel time: Hamadneh and Esztergár-Kiss report 13–42% travel-time reductions, supporting the interpretation that SAVs could meaningfully reduce delays in indirect inter-peripheral Lisbon trips [

12].

Energy and emissions: Fagnant and Kockelman demonstrate 12% energy-use reduction and 5.6% GHG reduction per shared autonomous vehicle when compared with typical light-duty vehicles [

13].

Operational efficiency: Fagnant and Kockelman modelling also shows that each SAV can replace around 11 conventional vehicles, though this introduces roughly 10% additional vehicle-kilometres due to empty repositioning [

13].

Accessibility: Gains of 13–17% under AV-supported demand-responsive service structures (Dianin et al. [

14]) provide relevant proxies for Lisbon’s outer municipalities.

User acceptance indicators further contextualise feasibility. Moreno et al. [

29] reports 41.5% willingness to adopt SAVs; Haboucha et al. [

30] find that 24% of mode-choice decisions favour SAVs; and a Lisbon-specific study by Vicente [

31] shows 44% acceptance of CASE vehicles, providing a localised proxy for early SAV adoption potential.

All these numbers come from published research, showing clearly that benefits exist where automation is combined with strong oversight, solid systems, or effective digital planning. Without such elements—governance, setup, coordination—the technology by itself will not work well. When they are present, progress becomes visible—not merely theoretical but proven through results.

6.5. Policy and Planning Implications

The study shows the model is not just technical—it acts like a guide for decision making, showing how organisations, databases, and structures must work together. These outcomes break down clearly into three practical policy zones.

1. Data and System Interoperability. Clear data rules, common MaaS systems, or steady live updates must be in place. Otherwise, cooperation among providers fails. The framework shows interoperability matters greatly—it enables all further progress. One expert reinforced this need plainly: “Integration with existing platforms is crucial; otherwise the service will fail to coordinate with the rest of the network.”

2. Safety, Trust, and Risk Management. People avoid using systems they doubt. Because clear oversight is shown, along with open safety stats and fast response options, confidence grows. These features gain credibility through real-time updates, ongoing user input, and structured messaging paths built into the software level. As a user said, “I would feel safer if there were cameras, an emergency button, and someone watching in real time.”

3. Sustainability Alignment. The environmental argument is supported by data: electric SAV fleets reduce energy consumption while lowering emissions. Yet benefits depend on how well they connect to broader transit aims. The documented energy and emissions reductions of 12% and 5.6% per vehicle offer an initial sustainability benchmark for municipal planning [

13]. One passenger highlighted this expectation: “It should be more environmentally reliable than an Uber—otherwise what’s the point?”

In brief, the framework suggests that merging information, earning trust from citizens, while ensuring long-term function, needs parallel growth. Governance should not handle these as isolated paths—progress occurs only when linked into a single network.

6.6. Contributions of the Reference Model

The reference model offers a structured, context-adapted representation of the organisational, digital, and technological requirements for SAV deployment in Lisbon.

By combining enterprise architecture modelling with empirically supported performance indicators, the model bridges conceptual planning and quantitative impact interpretation while providing a replicable framework for medium-sized European cities to assess how SAVs might integrate into existing mobility networks, reinforcing their value as a tool for policy formation, system design, and strategic scenario evaluation.

6.7. Comparison with Existing SAV Deployment Frameworks

Current SAV models vary widely—one differs from another in range or basis, so the Lisbon framework ends up distinct—not rivalling them but addressing what they miss.

Simulation-based research by Vosooghi et al. [

8], along with Fagnant and Kockelman [

13], focuses strongly on efficiency improvements: smooth path planning, precise vehicle coordination, efficient code—yet oversight mechanisms are nearly absent. In these frameworks, organisations appear more as a passive context than active players. Conversely, regulatory analyses like Milakis and Seibert [

7] or Carrese et al. [

15] examine rule design and integration with mobility services yet seldom detail the technical setup needed to enforce such policies. These result in existing plans but no operational backbone to support them.

In this context, the Lisbon approach links three areas typically studied apart: multilevel governance structures; sharing data via one integrated MaaS system; and an implementation approach outlined using enterprise architecture techniques. The combination creates a mixed system connecting simulated ideas with practical organisational capabilities—a mismatch seen repeatedly in European initiatives.

The use of ArchiMate aligns the model with enterprise-architecture approaches for mobility, such as those proposed by Rosa et al. [

17], yet it goes beyond them. Rather than stopping at standard components, it introduces an additional level focused on trust, safety, and input from users, which are aspects often left out in technical designs. Contrasting with models that view people indirectly, this one clearly defines where assistance mechanisms, oversight instruments, and protective functions fit within the structure.

As a result, the Lisbon framework is neither just an operational guide nor a vague policy outline. Instead, it functions as a connected system—responsive to context—that ties together organisations, information movement, and vehicle management principles, along with how users, interact within a single setup.

6.8. Integration with the State of the Art

The Lisbon model’s assessment reflects trends seen in SAV studies but also highlights areas most models ignore. Results match those of Hamadneh and Esztergár-Kiss [

12] along with Fagnant and Kockelman [

13]: gains are not just about automated tech. Instead, they depend on service design, user demand shifts, or coordination across providers. Interviews here raised a similar concern: split responsibilities among agencies. Previously, Carrese et al. [

15], along with Milakis and Seibert [

7], pointed this out—yet interview findings sharpened its urgency. When agencies do not sync up, efforts at improvement stall from the start.

What sets this model apart lies in its approach to governance along with interoperability. Rather than seeing these as general policy issues, it integrates them into working parts via enterprise architecture. Research relying on simulations often presumes seamless coordination—settings where departments align perfectly, while analyses centred on policy outline regulations seldom detail actual system design. The Lisbon approach fills this gap because it links management, information movement, and tech execution within a framework built on the city’s real digital infrastructure and transport conditions.

7. Conclusions

This study designed and validated a reference model for the deployment of Shared Autonomous Vehicles in Lisbon, applying the Design Science Research Methodology to create an artefact grounded in both literature and contextual analysis. The research addressed a gap existing between adapting a previously validated international reference model to the particular governance conditions, infrastructure and social contexts for a medium-sized European city.

Combining qualitative findings with real performance data from SAV simulations shows the model’s practical value. Because it offers actionable guidance, planners may apply it during initial mobility planning or when evaluating different scenarios.

When used in Lisbon, the model reveals that aligned management, common digital platforms, and electric vehicles together support a better integrated transit setup. Support from specialists confirmed this—analysis showed it works well within current local government roles. From the riders’ perspective, a prominent insight emerged: real-world success depends on reliability, security, and ease of access.

Scenario-based interpretation, grounded exclusively in verifiable metrics—including travel-time reductions of 13–42% [

12], energy-use reductions of 12%, GHG reductions of 5.6% [

13], and accessibility improvements of 13–17% in peripheral areas [

14]—strengthens the artefact’s analytical relevance. In line with documented fleet-level findings, the interpretation also considers evidence showing that one SAV may replace around 11 conventional vehicles although potentially generating approximately 10% additional VKT due to empty repositioning [

13].

7.1. Main Contributions

The principal contribution of this research lies in the development of a Lisbon-specific reference model that synthesises governance structures, data-driven mobility platforms, and autonomous vehicle technologies into a unified framework.

Its layered architecture links strategic mobility objectives to operational processes, enabling planners and policymakers to evaluate SAV integration using both organisational and performance-based perspectives.

Methodologically, the study demonstrates how enterprise architecture modelling can operationalise DSRM in mobility contexts, producing artefacts that are both theoretically grounded and empirically validated.

This contributes to the growing body of work exploring structured approaches to the integration of emerging mobility technologies in complex urban governance systems.

7.2. Limitations

The model, treated as a theoretical construct, underwent purely qualitative testing—no real-world use nor any simulation-driven refinement. Insights were gathered from both specialists and end-users; however, due to the small participant group, findings are not broadly representative at this stage.

The rules around self-driving cars keep changing. While regulations develop, certain elements of the model’s oversight and risk systems might require updates to remain useful.

Economic factors, along with how operational mechanisms—like costs versus benefits, money sources, plus how expanding SAV groups function—were not covered here. These areas remain unanswered for now, particularly should Lisbon or comparable urban centres choose to run broad self-driving trials in real conditions.

Additionally, although the scenario interpretation used strictly documented KPIs such as 13–42% travel-time gains [

12], 12% energy reduction, 5.6% GHG reduction, 11:1 vehicle replacement ratios, 10% additional VKT from repositioning [

13], and 13–17% accessibility improvements [

14], these values originate from international studies and not from Lisbon-specific modelling. This limits the precision with which local system-wide impacts can be projected.

The model was checked through qualitative methods alone, meaning insights reflect its logical structure and usefulness in practice yet reveal little about individual parts facing actual operational demands. In the absence of numerical analysis, judging the performance strength of elements such as compatibility systems or monitoring interfaces becomes difficult—especially when cars, cloud hubs, and mobility networks run simultaneously at peak capacity.

Regulations bring extra complexity. As laws on self-driving transport and data compatibility change over time, so must certain system elements (like governance processes or security setups) adapt alongside them. This creates ongoing unpredictability that planners must account for from the start.

Some places allow the model to move more freely than others. In mid-sized EU cities, rules on mobility vary a lot, and so do digital readiness levels along with public openness towards automated transit options. Due to such differences across regions, transferring the framework requires careful thought. While it may support local adjustments, direct replication is not feasible without modifications.

7.2.1. Risk and Mitigation Framework

To complement the discussion of limitations,

Table 6 presents a risk–response matrix outlining the main technical, regulatory, and operational risks associated with SAV deployment, together with proposed mitigation actions derived from the reference model.

This matrix strengthens the practical applicability of the reference model by clarifying risk conditions and aligning them with specific governance, technological, and operational safeguards.

7.2.2. Generalisability of Findings

The results require close attention before use beyond Lisbon’s urban zone. In Europe, mid-sized cities may seem alike at first glance—overlapping authorities, fragmented providers, and outdated transport systems shaped by years of change. However, when examining digital readiness, regional policies, or community integration patterns, contrasts emerge clearly. These gaps turn out to be significant upon closer inspection.

The reference model moves from place to place—but not as an exact replica. While it might function in cities such as Porto, Valencia, or Ghent, every location requires specific changes; these include decision-making roles, the current progress of MaaS initiatives, and available data infrastructure along with public attitudes towards automation. Thanks to the enterprise architecture design, adapting the framework becomes more manageable—yet each implementation demands real-world trials to see if the system truly aligns with local conditions.

7.3. Future Work

Future research should combine simulation and scenario modelling to assess performance and environmental impact under real deployment conditions. Economic evaluation and business model analysis are also essential to ensure long-term viability. Finally, pilot projects or living labs in selected corridors could validate user trust, safety, and adoption patterns. These initiatives should align with the European Commission’s Autonomous Drive Ambition Cities programme [

32], enabling Lisbon to position itself as a leading case for shared autonomous mobility in Europe.

Further work should also integrate digital-twin environments, enabling a more robust calibration of the KPIs used in this study—including travel-time impacts, emissions, accessible-area growth, and user-acceptance estimates—within dynamic, data-driven urban mobility simulations.

In summary, the research provides a structured, context-sensitive framework that connects theoretical design with practical urban application, offering a solid foundation for the gradual introduction of Shared Autonomous Vehicles in Lisbon.