Topological Optimization of Lumbar Intervertebral Fusion Cage with Posterior Pedicle Screw Oblique Insertion Fixation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Construction and Validation of a Complete Lumbar Finite Element Model

2.2. Weighted Topology Optimization for Cage Design

2.3. Static Analysis of Topologically Optimized Cage Structure and Internal Fixation System

- (A)

- Conventional Cage combined with pedicle screw oblique insertion internal fixation surgical model (using Ø5 × 50 mm screws), where the conventional Cage structure was designed considering screw configuration and surgical space constraints.

- (B)

- Topologically optimized Cage combined with pedicle screw oblique insertion internal fixation surgical model (using Ø5 × 50 mm screws).

- (C)

- Topologically optimized Cage combined with traditional pedicle screw and titanium rod internal fixation surgical model (using Ø5 × 50 mm screws and a Ø6 mm titanium rod).

3. Results

3.1. Validation

3.2. Static Results

3.2.1. Endplate Stress

3.2.2. Cage Stress

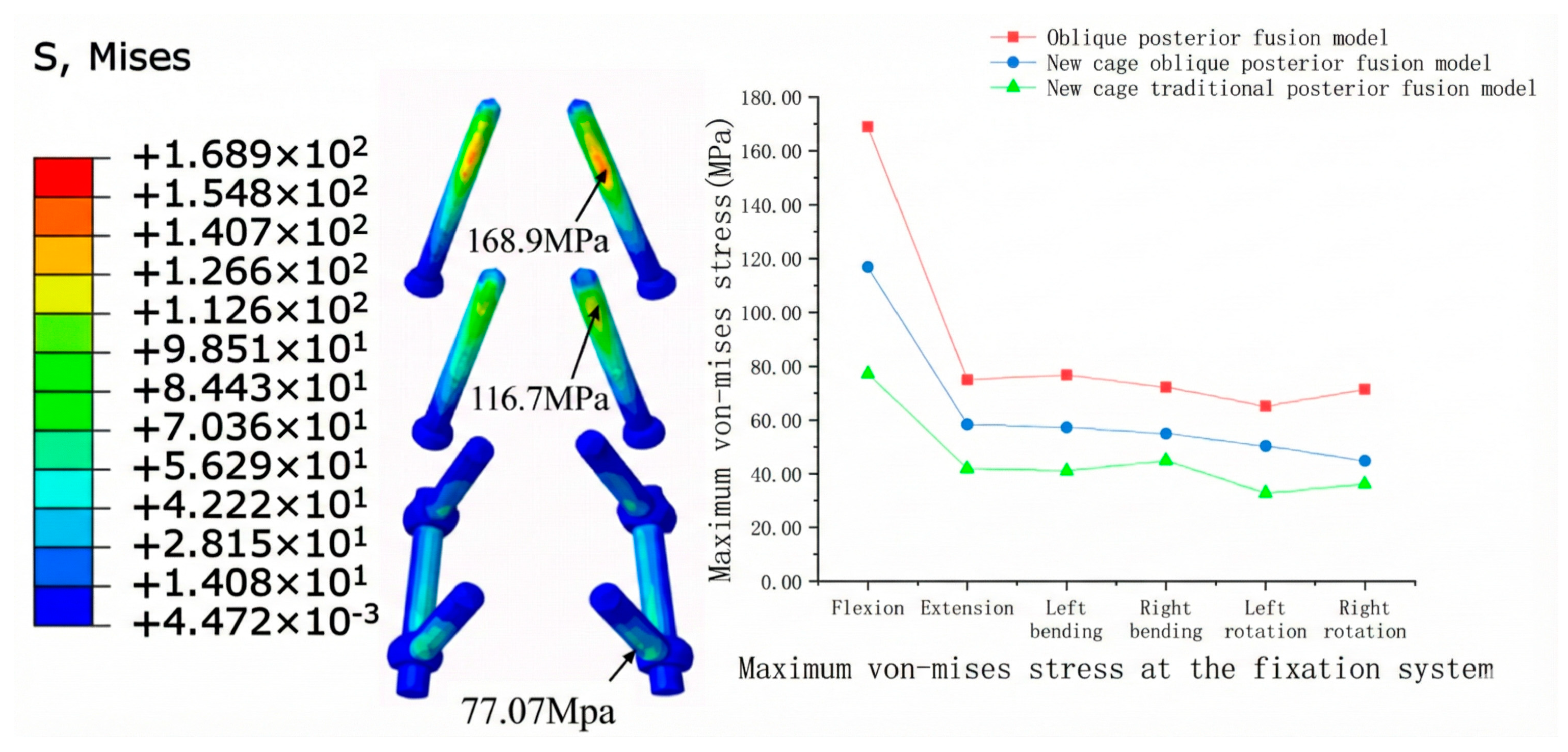

3.2.3. Internal Fixation Stress

4. Dynamic Results

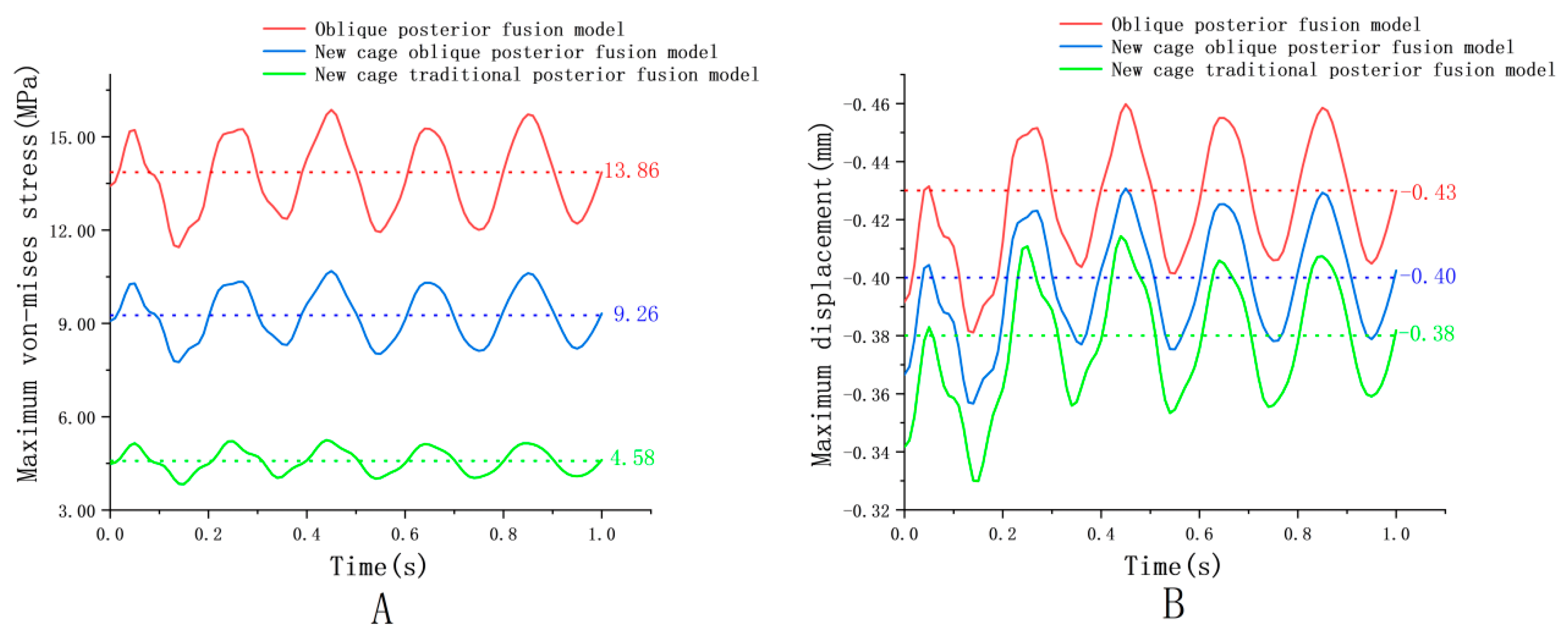

4.1. Cage Dynamic Response

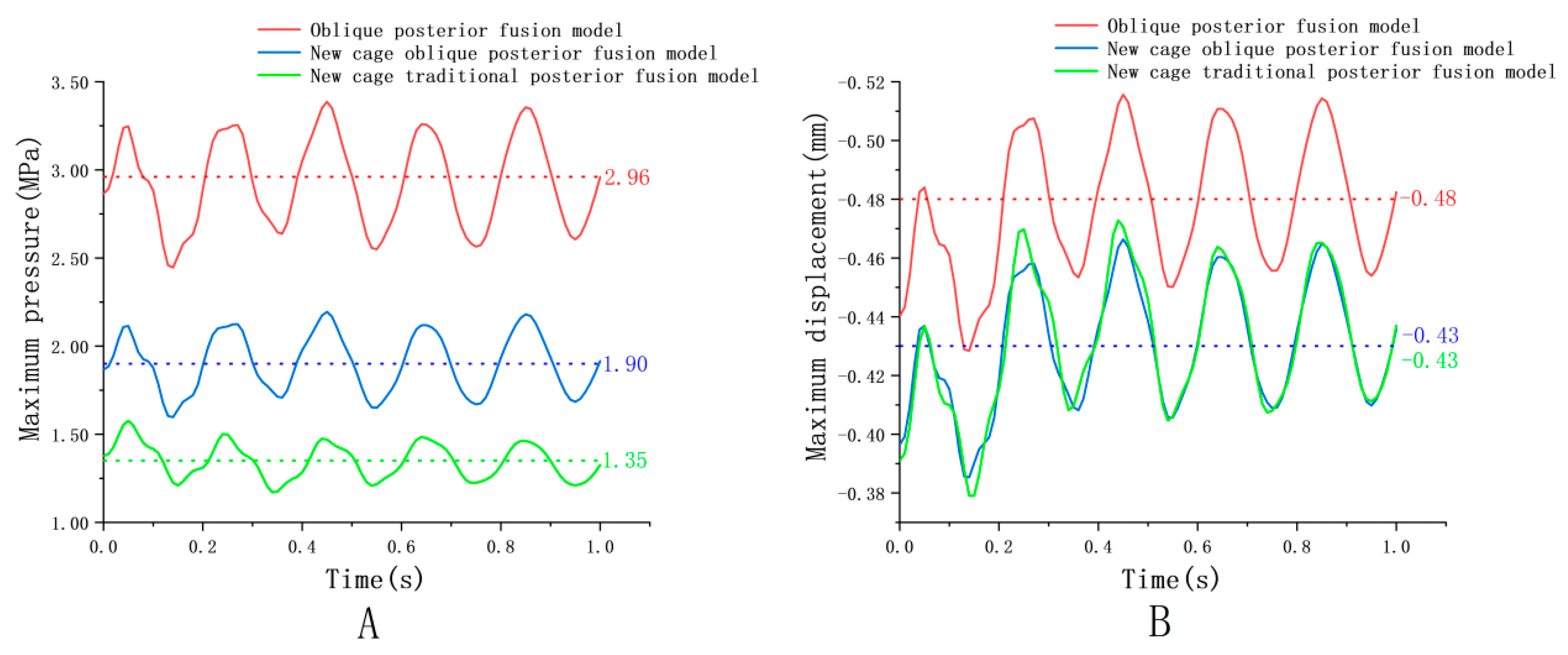

4.2. Endplate Dynamic Response

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meng, B.; Bunch, J.; Burton, D.; Wang, J. Lumbar interbody fusion: Recent advances in surgical techniques and bone healing strategies. Eur. Spine J. 2021, 30, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, M.G.; Haid, R.W., Jr.; Subach, B.R.; Barnes, B.; Rodts, G.E., Jr. Anterior cervical plating enhances arthrodesis after discectomy and fusion with cortical allograft. Neurosurgery 2002, 50, 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Chao, B.; Liu, S.; Luo, W.; Jiao, J.; Wu, M. Biomaterials for Interbody Fusion in Bone Tissue Engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 900992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-D.; Chen, Q.; Ding, W.-Y.; Zhao, J.-Q.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Shen, Y.; Yang, D.-L. Unilateral Pedicle Screw Fixation with Bone Graft vs. Bilateral Pedicle Screw Fixation with Bone Graft or Cage: A Comparative Study. Med. Sci. Monit. 2016, 22, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Fogel, G.R.; Xiang, D.; Liao, Z.; Liu, W. Finite element model predicts the biomechanical performance of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with various porous additive manufactured Cages. Comput. Biol. Med. 2018, 95, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Luo, Z. A study on the structural properties of the lumbar endplate: Histological structure, the effect of bone density, and spinal level. Spine 2009, 34, E427–E433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, K.; Mobbs, R.J. Evolution of Design of Interbody Cages for Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion. Orthop. Surg. 2016, 8, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Closkey, R.F.; Parsons, J.R.; Lee, C.K.; Blacksin, M.F.; Zimmermant, M.C. Mechanics of Interbody Spinal Fusion: Analysis of Critical Bone Graft Area. Spine 1993, 18, 1011–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Feng, Q.; Yang, D.; Xu, H.; Wen, W.; Xu, H.; Miao, J. Biomechanical evaluation of different sizes of 3D printed Cage in lumbar interbody fusion—A finite element analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Guo, Q. Biomechanical Optimization of Lumbar Fusion Cages with a Porous Design: A Finite Element Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2023, 15, 5384. [Google Scholar]

- Young, C.J.; Hoon, S.K. Subsidence after anterior lumbar interbody fusion using paired stand-alone rectangular Cages. Eur. Spine J. 2006, 15, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.X.; Fan, W. Dynamic Response of the Lumbar Spine to Whole-body Vibration Under a Compressive Follower Preload. Spine 2018, 43, E143–E153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; Zhu, J.; Huang, C.; Xiang, D.; Liu, W. Effect of Interbody Implants on the Biomechanical Behavior of Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion: A Finite Element Study. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgiou, I.; Delisola, F.; Andreos, U.; Misra, A. A orthotropic evolving substructure continuum model for bone remodeling: Mechanistic explanations behind Wolff’s law. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2023, 22, 2135–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allena, R.; Rémond, Y. How mechanotherapy drives bone remodeling? Math. Mech. Complex Syst. 2025, 13, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Kettler, A.; Heuer, F.; Simon, U.; Claes, L.; Wilke, H.-J. Intradiscal pressure, shear strain, and fiber strain in the intervertebral disc under combined loading. Spine 2007, 32, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazal, J.; Tanguy, A.; Bourges, M.; Gaurel, G.; Escande, G.; Guillot, G.; Vanneuville, G. Biomechanical properties of spinal ligaments and a histological study of the supraspinal ligament in traction. J. Biomech. 1985, 18, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.F.; Chang, C.M.; Liao, C.Y.; Chan, Y.T.; Li, Z.Y.; Lin, C.L. Biomechanical evaluation of an osteoporotic anatomical 3D printed posterior lumbar interbody fusion Cage with internal lattice design based on weighted topology optimization. Int. J. Bioprint. 2023, 9, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-S.; Hu, H.-T.; Lin, R.-M.; Lee, H.-C.; Lai, P.-L.; Chen, W.-W. Biomechanical analysis of the lumbar spine on facet joint force and intradiscal pressure: A finite element study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2010, 11, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rich, M.; Arnoux, P.-J.; Wagnac, E.; Brunet, C.; Aubin, C.-E. Finite element investigation of the loading rate effect on the spinal load-sharing changes under impact conditions. J. Biomech. 2009, 42, 1252–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Guo, L.X.; Zhang, M. Biomechanical analysis of lumbar interbody fusion supplemented with various posterior stabilization systems. Eur. Spine J. 2021, 30, 2342–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahaer, A.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Luan, H.; Maimaiti, A.; Liu, D.; Shi, W.; Zhang, T.; Guo, H.; Rexiti, P. Hybrid pedicle screw and modified cortical bone trajectory technique in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion at L4-L5 segment: Finite element analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; Chen, Y.; Liao, Z.; Liu, W. Biomechanical evaluation of anterior lumbar interbody fusion with various fixation options: Finite element analysis of static and vibration conditions. Clin. Biomech. 2021, 84, 105339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, I.; Panjabi, M.M.; Crisco, T.; Oxland, T. Three-dimensional movements of the whole lumbar spine and lumbosacral joint. Spine 1989, 14, 1256–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmoelz, W.; Huber, J.F.; Nydegger, T.; Claes, L.; Wilke, H.J. Dynamic Stabilization of the Lumbar Spine and Its Effects on Adjacent Segments: An In Vitro Experiment. Clin. Spine Surg. 2003, 16, 418–423. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.-H.; Wu, C.-H.; Lin, C.-L. Design of a patient-specific mandible reconstruction implant with dental prosthesis for metal 3D printing using integrated weighted topology optimization and finite element analysis. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 105, 103700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, D.-X.; Guo, L.-X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Q.-D. Biomechanical Evaluation of Rigid Interspinous Process Fixation Combined with Lumbar Interbody Fusion Using Hybrid Testing Protocol. J. Biomech. Eng. 2023, 145, 064501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Chen, X.; Li, K.; Li, Z.; Li, S. Finite analysis of stability between modified articular fusion technique, posterior lumbar interbody fusion and posteriorlateral lumbar fusion. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-S.; Cheng, C.-K.; Liu, C.-L.; Lo, W.-H. Stress analysis of the disc adjacent to interbody fusion in lumbar spine. Med. Eng. Phys. 2001, 23, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-F.; Liu, Z.-D.; Dai, L.-Y.; Zhong, G.-B.; Zang, W.-P. Dynamic response of the idiopathic scoliotic spine to axial cyclic loads. Spine 2011, 36, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yang, J.; Lieberman, I.; Haddas, R. Finite element method-based study for effect of adult degenerative scoliosis on the spinal vibration characteristics. Comput. Biol. Med. 2017, 84, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, L.; Chen, R.; Li, Z.; Xu, W. Biomechanical evaluation of different oblique lumbar interbody fusion constructs: A finite element analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 25, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, V.K.; Park, H.; Kong, W. Investigation of Vibration Characteristics of the Ligamentous Lumbar Spine Using the Finite Element Approach. J. Biomech. Eng. 1994, 116, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, W.Z.; Goel, V.K. Ability of the finite element models to predict response of the human spine to sinusoidal vertical vibration. Spine 2003, 28, 1961–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.-X.; Teo, E.-C. Prediction of the Modal Characteristics of the Human Spine at Resonant Frequency Using Finite Element Models. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J. Eng. Med. 2005, 219, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.-X.; Wang, Z.-W.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Lee, K.-K.; Teo, E.-C.; Li, H.; Wen, B.-C. Material property sensitivity analysis on resonant frequency characteristics of the human spine. J. Appl. Biomech. 2009, 25, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabaha, S.; Tej, C.B.; Kumar, G.S. A comprehensive analysis on the processing-structure-property relationships of FDM-based 3-D printed polyetheretherketone (PEEK) structures. Materialia 2022, 22, 101427. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Judith, M.R.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, V.; Robert, M.C. Analysis of stress distribution in lumbar interbody fusion. Spine 2005, 30, 1731–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Element Type | Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Density (kg/mm3) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical bone | C3D4 | 12,000 | 0.3 | 1.83 × 10−6 | [18,20] |

| Cancellous bone | C3D4 | 100 | 0.2 | 1.70 × 10−7 | [18,20] |

| Endplate | C3D4 | 500 | 0.25 | 1.20 × 10−6 | [19,23] |

| Annulus ground substance | C3D8H | 4.2 | 0.45 | 1.05 × 10−6 | [18,23] |

| Nucleus pulpous | C3D8H | Hyperelastic, Mooney–Rivlin C10 = 0.12, C01 = 0.03 | 1.02 × 10−6 | [21,23] | |

| Facet joint cartilage | C3D8H | 24 | 0.4 | 1.0 × 10−6 | [22,23] |

| Cage (PEEK) | C3D4 | 3600 | 0.25 | 1.32 × 10−6 | [21,23] |

| Pedicle Screws | C3D4 | 110,000 | 0.3 | 4.5 × 10−6 | [18,23] |

| Titanium rods | C3D4 | 110,000 | 0.3 | 4.5 × 10−6 | [18,23] |

| Ligaments | Element Type | Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Density (kg/mm3) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior longitudinal | T3D2 | 7.8 | 63.7 | 1.0 × 10−6 | [21,23] |

| Posterior longitudinal | T3D2 | 10 | 20 | 1.0 × 10−6 | [22,23] |

| Ligamentum flavum | T3D2 | 15 | 40 | 1.0 × 10−6 | [21,23] |

| Supraspinous | T3D2 | 8 | 30 | 1.0 × 10−6 | [21,23] |

| Interspinous | T3D2 | 4.56 | 40 | 1.0 × 10−6 | [20,21,23] |

| Intertransverse | T3D2 | 10 | 1.8 | 1.0 × 10−6 | [21,23] |

| Capsular | T3D2 | 7.5 | 30 | 1.0 × 10−6 | [21,23] |

| Dynamic Responses | Oblique Model | New Cage Oblique Model | New Cage Traditional Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Min | Amplitude | Max | Min | Amplitude | Max | Min | Amplitude | |

| Von-mises (MPa) | |||||||||

| Cage | 15.87 | 11.45 | 4.42 | 10.68 | 7.76 | 2.92 | 5.25 | 3.83 | 1.42 |

| Displacement (mm) | |||||||||

| Cage | −0.46 | −0.38 | 0.08 | −0.43 | −0.36 | 0.07 | −0.41 | −0.33 | 0.08 |

| Endplate | −0.52 | −0.43 | 0.09 | −0.47 | −0.39 | 0.08 | −0.47 | −0.38 | 0.09 |

| Pressure (MPa) | |||||||||

| Endplate | 3.39 | 2.45 | 0.94 | 2.20 | 1.60 | 0.60 | 1.58 | 1.17 | 0.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, H.; Fei, J.; Deng, J.; Zhao, X. Topological Optimization of Lumbar Intervertebral Fusion Cage with Posterior Pedicle Screw Oblique Insertion Fixation. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010524

He H, Fei J, Deng J, Zhao X. Topological Optimization of Lumbar Intervertebral Fusion Cage with Posterior Pedicle Screw Oblique Insertion Fixation. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):524. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010524

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Hong, Jiyou Fei, Jun Deng, and Xing Zhao. 2026. "Topological Optimization of Lumbar Intervertebral Fusion Cage with Posterior Pedicle Screw Oblique Insertion Fixation" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010524

APA StyleHe, H., Fei, J., Deng, J., & Zhao, X. (2026). Topological Optimization of Lumbar Intervertebral Fusion Cage with Posterior Pedicle Screw Oblique Insertion Fixation. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010524