Siderite as a Functional Substrate for Enhanced Nitrate and Phosphate Removal in Tidal Flow Constructed Wetlands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Siderite, Wetland Plants, and Microbial Inoculum Source

2.2. Constructed Wetland Setup, Synthetic Wastewater Preparation, and Operation

2.3. Effluent Sampling and Analysis

2.4. Determination of Microbial Community Diversity

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Impact of Siderite Dosage and Influent COD/N on the Elimination and Conversion of NO3−-N

3.2. Impact of Siderite Dosage and Influent COD on PO43−-P Removal

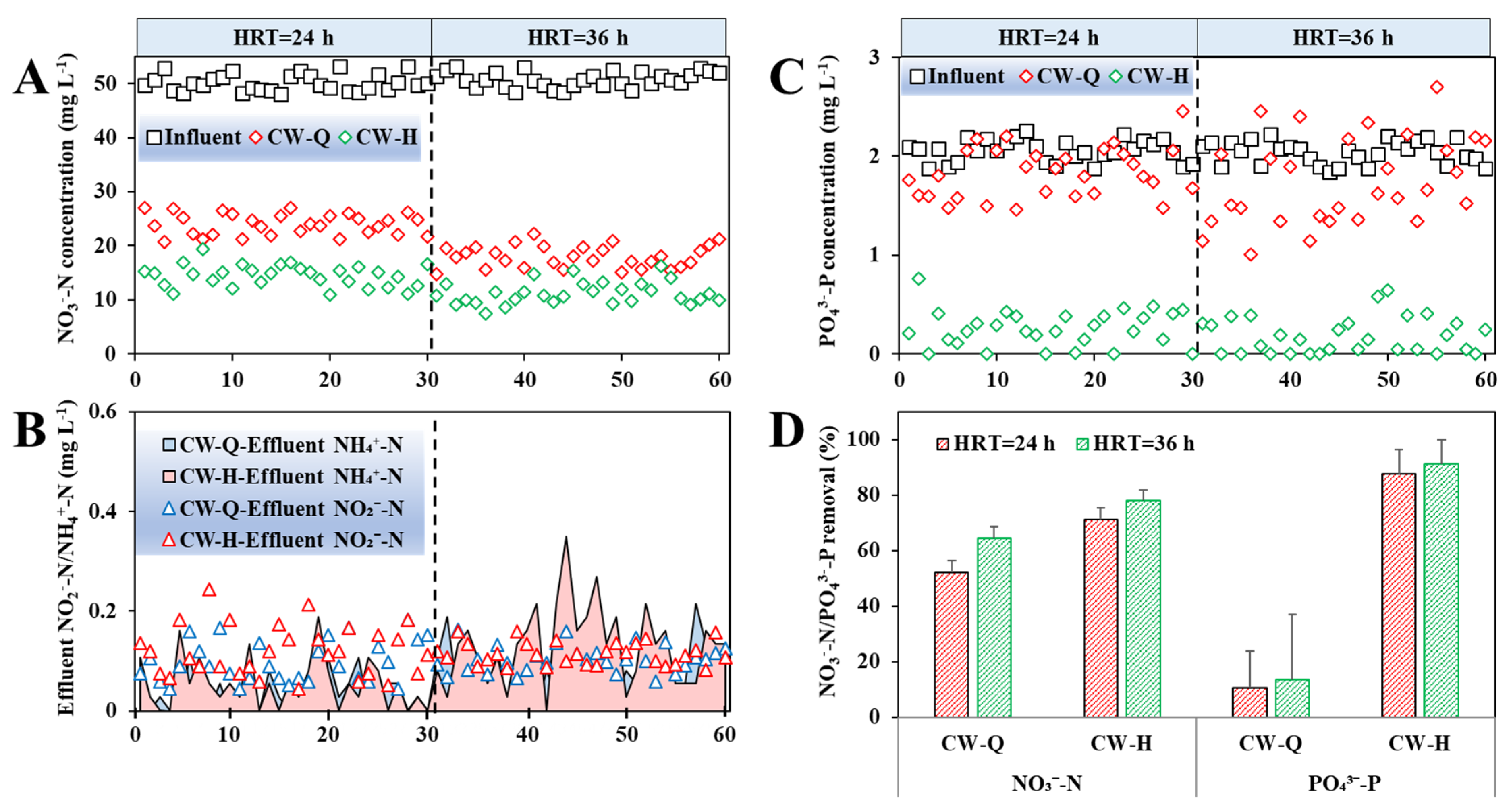

3.3. Impact of Hydraulic Retention Time (HRT) on NO3−-N and PO43−-P Removal

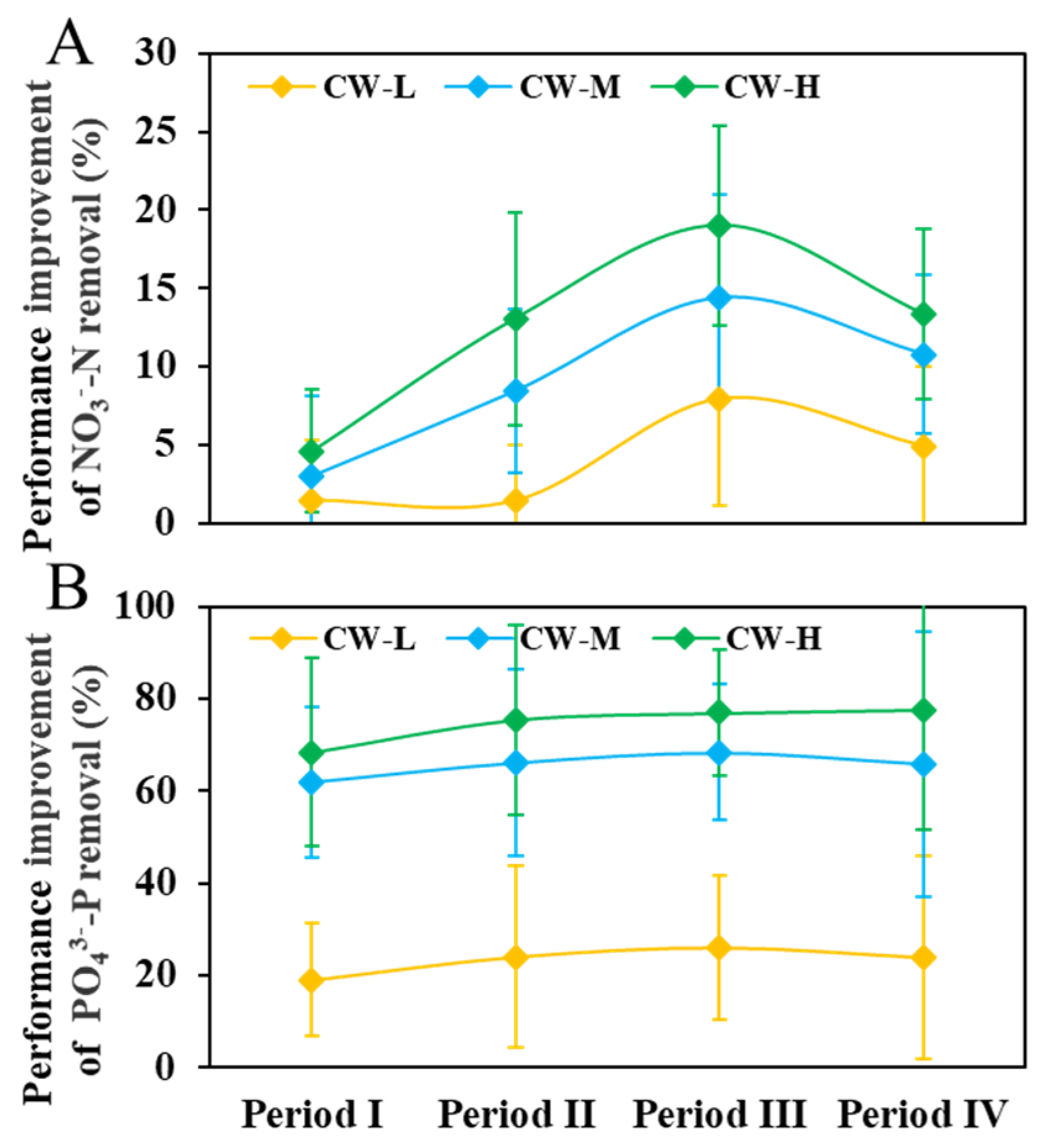

3.4. Quantitative Assessment of the Improvement in NO3−-N and PO43−-P Removal in CWs

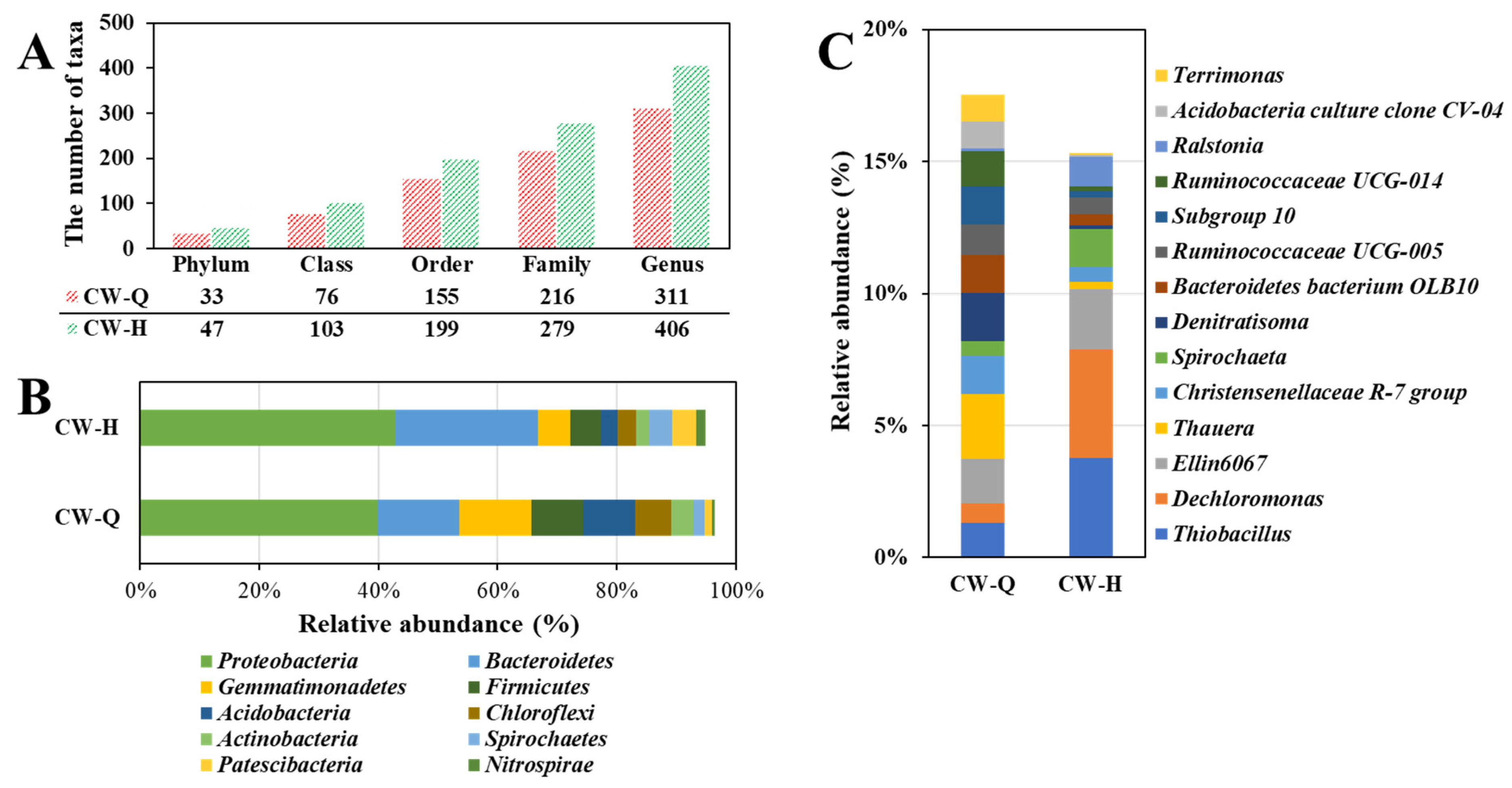

3.5. Microbial Communities on Wetland Substrate Surfaces

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Siderite enhanced the NO3−-N removal performance in CWs. The improvement is predominantly influenced by the dosage of siderite and the presence of organic carbon in the influent. Under carbon-limited conditions, the improvement in denitrification facilitated by siderite-driven autotrophic pathways is constrained. However, when an external organic carbon source is introduced, siderite-amended CWs demonstrate markedly superior NO3−-N removal efficiency compared to non-siderite CWs. Under an influent NO3−-N concentration of approximately 50 mg L−1 and COD/N ratios of 2 and 5, a 50% siderite substrate mass ratio yielded average NO3−-N removal enhancements of 13.07 ± 6.80% and 19.01 ± 6.37%, respectively, at a 24 h-HRT.

- (2)

- The improvement of PO43−-P removal by siderite was directly influenced by its dosage. At a 50% siderite proportion and an influent PO43−-P of 2 mg L−1, the PO43−-P removal efficiency was increased by 76.98 ± 13.82% over the control at 24 h-HRT.

- (3)

- The application of siderite increased both richness and evenness of the wetland microbial community. Prominent functional genera, including Dechloromonas (a denitrifying polyphosphate-accumulating organism) and Thiobacillus (an autotrophic denitrifier capable of utilizing CO2 as a carbon source), exhibited increased relative abundances in the siderite-amended CW compared to the control.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, G.; Li, Q.; Cai, R.; Mao, G.; Miao, R.; Liu, M.; Li, D.; Song, C. Quantitative effects of substrate, vegetation, and hydraulic loading on pollutant removal in constructed wetlands. Ecol. Eng. 2026, 223, 107836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntountounakis, I.; Margaritou, I.E.; Pervelis, I.; Kyrou, P.; Parlakidis, P.; Gikas, G.D. Pollutant removal efficiency of pilot-scale horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetlands treating landfill leachate. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, G.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Feng, Y. A review of enhanced strategies for nitrogen removal in constructed wetlands: From design, influencing factors to full-scale applications and challenges. Water Res. 2026, 288, 124662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, R.; Yan, P.; Wu, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, C.; Hu, Z.; Zhuang, L.; Guo, Z.; et al. Constructed wetlands for pollution control. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vymazal, J. Nitrogen removal in constructed wetlands. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2025, 48, 100668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dong, J.; Liu, L.; Zhu, G.; Liu, C. Screening of phosphate-removing substrates for use in constructed wetlands treating swine wastewater. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 54, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, K.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, T.; Wen, D.; Liu, A.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Z. Recent advances of constructed wetlands utilization under cold environment: Strategies and measures. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 201, 107530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, X.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, Y. Selection and optimization of the substrate in constructed wetland: A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 49, 103140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Qiu, L.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Nie, F.; Jiang, Q.; Cao, W. Study on substrates purification effect and microbial community structure of vertical subsurface flow constructed wetland under siphon effect. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 68, 106594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Liu, H.; Chu, Z.; Zhai, P.; Chen, T.; Wang, H.; Zou, X.; Chen, D. The effect of isomorphic substitution on siderite activation of hydrogen peroxide: The decomposition of H2O2 and the yield of ·OH. Chem. Geol. 2021, 585, 120555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Jin, J.; Han, Y.; Tao, Y.; Lu, C. Sustainable exploitation of siderite ore using fluidization roasting technology without reductant. Miner. Eng. 2025, 234, 109749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, M.E.Y.; Sarmiento, S.A.; Vera, L.E.; Drozd, V.; Durygin, A.; Chen, J.; Saxena, S.K. Siderite decomposition at room temperature conditions for CO2 capture applications. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 38, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, F.; Putnis, C.V.; Montes-Hernandez, G.; King, H.E. Siderite dissolution coupled to iron oxyhydroxide precipitation in the presence of arsenic revealed by nanoscale imaging. Chem. Geol. 2017, 449, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiskira, K.; Papirio, S.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Esposito, G. Fe(II)-mediated autotrophic denitrification: A new bioprocess for iron bioprecipitation/biorecovery and simultaneous treatment of nitrate-containing wastewaters. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2017, 119, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Gao, J.; Liu, L.; Mao, Y.; Kang, H.; Song, Z.; Cai, M.; Guo, P.; Chen, K. Performance and by-product generation in sulfur-siderite/limestone autotrophic denitrification systems: Enhancing nitrogen removal efficiency and operational insights. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 123042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, X.; Yang, S.; Xu, Z.; Feng, C.; Zhao, F. Enhanced nitrogen removal driven by S/Fe2+ cycle in a novel hybrid constructed wetland. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 426, 139113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Hu, H.; Chen, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, Q.; Zeng, C.; Shi, Q.; Song, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q. In-situ production of iron flocculation and reactive oxygen species by electrochemically decomposing siderite: An innovative Fe-EC route to remove trivalent arsenic. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 441, 129884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Ren, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, K.; Li, Y. Enhancement of arsenic adsorption during mineral transformation from siderite to goethite: Mechanism and application. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, M.; Gür, F.; Tümen, F. Cr(VI) reduction in aqueous solutions by siderite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2004, 113, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danková, Z.; Bekényiová, A.; Štyriaková, I.; Fedorová, E. Study of Cu(II) adsorption by siderite and kaolin. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 15, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Guo, H. Fluoride adsorption on modified natural siderite: Optimization and performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 223, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Kong, G.; Yu, X.; Guo, Z.; Kang, Y.; Kuang, S.; Zhang, J. Strengthening effect of different iron minerals for perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulphonic acid removal in constructed wetlands: Mechanisms of electron transfer and microbial effect. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 486, 150199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhang, X.; Qing, C.; Wang, J.; Yue, Z.; Liu, H.; Yang, Z. Simultaneous removal of nitrate and phosphate from wastewater by siderite based autotrophic denitrification. Chemosphere 2018, 199, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wei, D.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R. Sulfur-siderite autotrophic denitrification system for simultaneous nitrate and phosphate removal: From feasibility to pilot experiments. Water Res. 2019, 160, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, C.; Wei, D.; Liu, X.; Luo, W. Optimization of “sulfur–iron–nitrogen” cycle in constructed wetlands by adjusting siderite/sulfur (Fe/S) ratio. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 363, 121336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, H.C.; Sun, Y.L.; Cheng, H.Y.; Lu, S.Y.; Wang, A.J. Application of the sulfur-siderite composite filler: A case study of augmented performance and synergistic mechanism for low C/N wastewater treatment in constructed wetland. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 475, 146376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, T.; Sumona, M.; Gupta, B.S.; Sun, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhan, X. Utilization of iron sulfides for wastewater treatment: A critical review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2017, 16, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, B.; Ouyang, M.; Graham, N.; Yu, W. Enhancement of phosphate adsorption during mineral transformation of natural siderite induced by humic acid: Mechanism and application. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 393, 124730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wan, J.; Zhu, B. Natural siderite and calcium-derived Siderite/Ca composites for wastewater phosphate adsorption: Preparation, properties and mechanism. Colloid. Surf. A 2025, 723, 137314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yao, J.; Ma, B.; Knudsen, T.S.; Yuan, C. Siderite’s green revolution: From tailings to an eco-friendly material for the green economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, C.R.; Cravotta, C.A.; Capo, R.C.; Hedin, B.C.; Vesper, D.J.; Stewart, B.W. Multi-decadal geochemical evolution of drainage from underground coal mines in the Appalachian basin, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ren, S.; Wang, P.; Wang, B.; Hu, K.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Li, W.; et al. Autotrophic denitrification using Fe(II) as an electron donor: A novel prospective denitrification process. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Li, H.; Dong, H.; Liu, L.; Zhou, C.; Du, Z.; Dang, Y.; Holmes, D.E. Magnetite-augmented sulfur-siderite autotrophic denitrification: Deep nitrogen removal at ultra-low HRT from lab to pilot scale. Water Res. 2025, 284, 124034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, T.; Miah, M.J.; Khan, T.; Ove, A. Pollutant removal employing tidal flow constructed wetlands: Media and feeding strategies. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 382, 122874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, C.; Hu, H.; Wang, Q.; Zeng, C. Phosphate removal from aqueous solution by electrochemical coupling siderite packed column. Chemosphere 2021, 280, 130805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, B.; Chen, T.; Liu, H.; Qing, C.; Xie, J.; Xie, Q. Removal of phosphate from aqueous solution by activated siderite ore: Preparation, performance and mechanism. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017, 80, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Fu, Y.Y.; Zhou, K.; Tian, T.; Li, Y.S.; Yu, H.Q. Microbial mixotrophic denitrification using iron(II) as an assisted electron donor. Water Res. X 2023, 19, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Gao, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, T. Fe(II) enhances simultaneous phosphorus removal and denitrification in heterotrophic denitrification by chemical precipitation and stimulating denitrifiers activity. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffner, C.; Holzapfel, S.; Wunderlich, A.; Einsiedl, F.; Schloter, M.; Schulz, S. Dechloromonas and close relatives prevail during hydrogenotrophic denitrification in stimulated microcosms with oxic aquifer material. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021, 97, fiab004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petriglieri, F.; Singleton, C.; Peces, M.; Petersen, J.F.; Nierychlo, M.; Nielsen, P.H. “Candidatus Dechloromonas phosphoritropha” and “Ca. D. phosphorivorans”, novel polyphosphate accumulating organisms abundant in wastewater treatment systems. ISME J. 2021, 15, 3605–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Picardal, F. Neutrophilic, nitrate-dependent, Fe(II) oxidation by a Dechloromonas species. World J. Microb. Biotechnol. 2013, 29, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, R.A.; Achenbach, L.A.; Coates, J.D. Reduction of (per)chlorate by a novel organism isolated from paper mill waste. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 1, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, Y.; Dong, H.; Min, J.; Xu, H.; Sun, D.; Liu, X.; Dang, Y.; Qiu, B.; Mennella, T.; et al. Evidence of autotrophic direct electron transfer denitrification (DETD) by Thiobacillus species enriched on biocathodes during deep polishing of effluent from a municipal wastewater treatment plant. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.L.; Beck, J.V. Evidence for the calvin cycle and hexose monophosphate pathway in Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. J. Bacteriol. 1967, 94, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qiu, S.; Guo, J.; Ge, S. Light irradiation enables rapid start-up of nitritation through suppressing nxrB gene expression and stimulating ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 13297–13305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Cui, L.; Wang, J.; Lei, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, R.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Zhai, X.; Zhang, M.; et al. Effects of low temperature on rhizosphere phosphate-mineralizing microbial populations in constructed wetlands. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, T.; Jin, X.; Deng, S.; Guo, K.; Gao, Y.; Shi, X.; Xu, L.; Bai, X.; Shang, Y.; Jin, P.; et al. Oxygen sensing regulation mechanism of Thauera bacteria in simultaneous nitrogen and phosphorus removal process. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wu, N.; Yuan, Y.; Ruan, L.; He, J. Degradation of atrazine by an anaerobic microbial consortium enriched from soil of an herbicide-manufacturing plant. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 81, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elad, T.; Tang, K.; Pierrelée, M.; Jensen, M.M.; Bentzon, T.M.; Smets, B.F.; Dechesne, A.; Valverde, P.B. An integrated meta-omics approach for identifying candidate organic micropollutant degraders in complex microbial communities. Water Res. 2025, 286, 124217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Components | Influent Concentration (mg L−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Startup Period | Period I | Period II | Period III | Period IV | |

| ZnSO4·2H2O | 10.8 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 10.8 |

| CuSO4·5H2O | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Na2MoO4·2H2O | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| MnSO4·H2O | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| CoCl2·6H2O | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| H3BO4 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 |

| MgCl2 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 |

| CaCl2 | 16.6 | 16.6 | 16.6 | 16.6 | 16.6 |

| KNO3 | 361.0 | 361.0 | 361.0 | 361.0 | 361.0 |

| KH2PO4 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| C6H12O6·H2O | 80.0 | 0 | 80.0 | 200.0 | 200.0 |

| CH3COONa | 25.7 | 0 | 25.7 | 64.3 | 64.3 |

| Sample | Good’s Coverage | Chao1 | Observed Species | Pielou’s Evenness | Simpson | Shannon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CW-Q | 0.998 | 3280.43 | 3274.4 | 0.786 | 0.992 | 9.173 |

| CW-H | 0.995 | 3751.75 | 3642.1 | 0.811 | 0.993 | 9.593 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, C.; Guo, Q.; He, S.; Si, Z. Siderite as a Functional Substrate for Enhanced Nitrate and Phosphate Removal in Tidal Flow Constructed Wetlands. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010515

Li C, Guo Q, He S, Si Z. Siderite as a Functional Substrate for Enhanced Nitrate and Phosphate Removal in Tidal Flow Constructed Wetlands. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):515. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010515

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Chengxue, Qihao Guo, Siteng He, and Zhihao Si. 2026. "Siderite as a Functional Substrate for Enhanced Nitrate and Phosphate Removal in Tidal Flow Constructed Wetlands" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010515

APA StyleLi, C., Guo, Q., He, S., & Si, Z. (2026). Siderite as a Functional Substrate for Enhanced Nitrate and Phosphate Removal in Tidal Flow Constructed Wetlands. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010515