Dynamic Response of a Double-Beam System Subjected to a Harmonic Moving Load

Abstract

1. Introduction

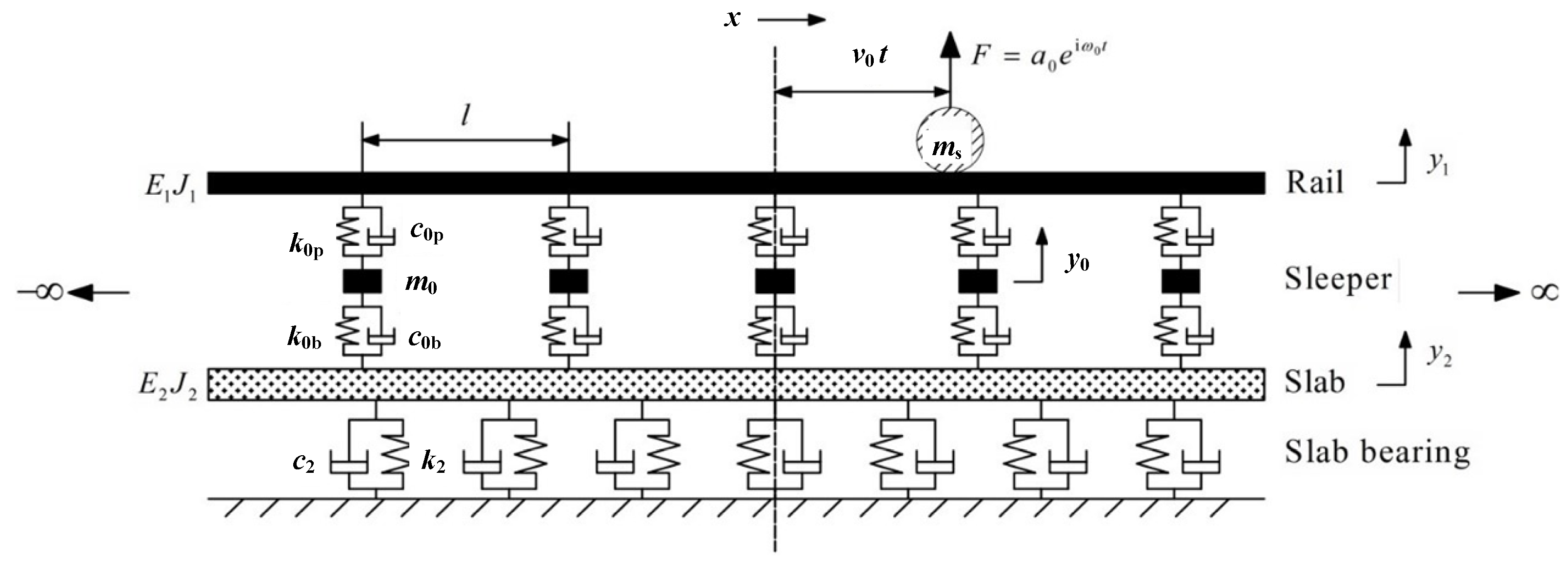

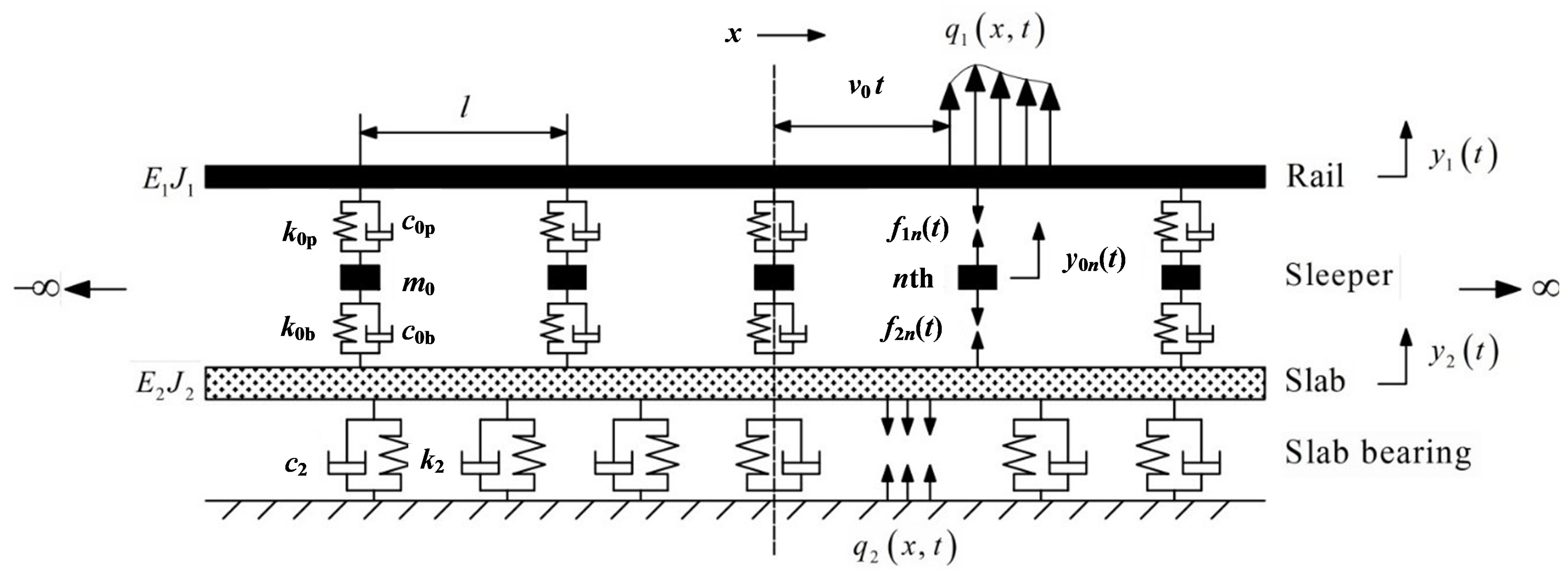

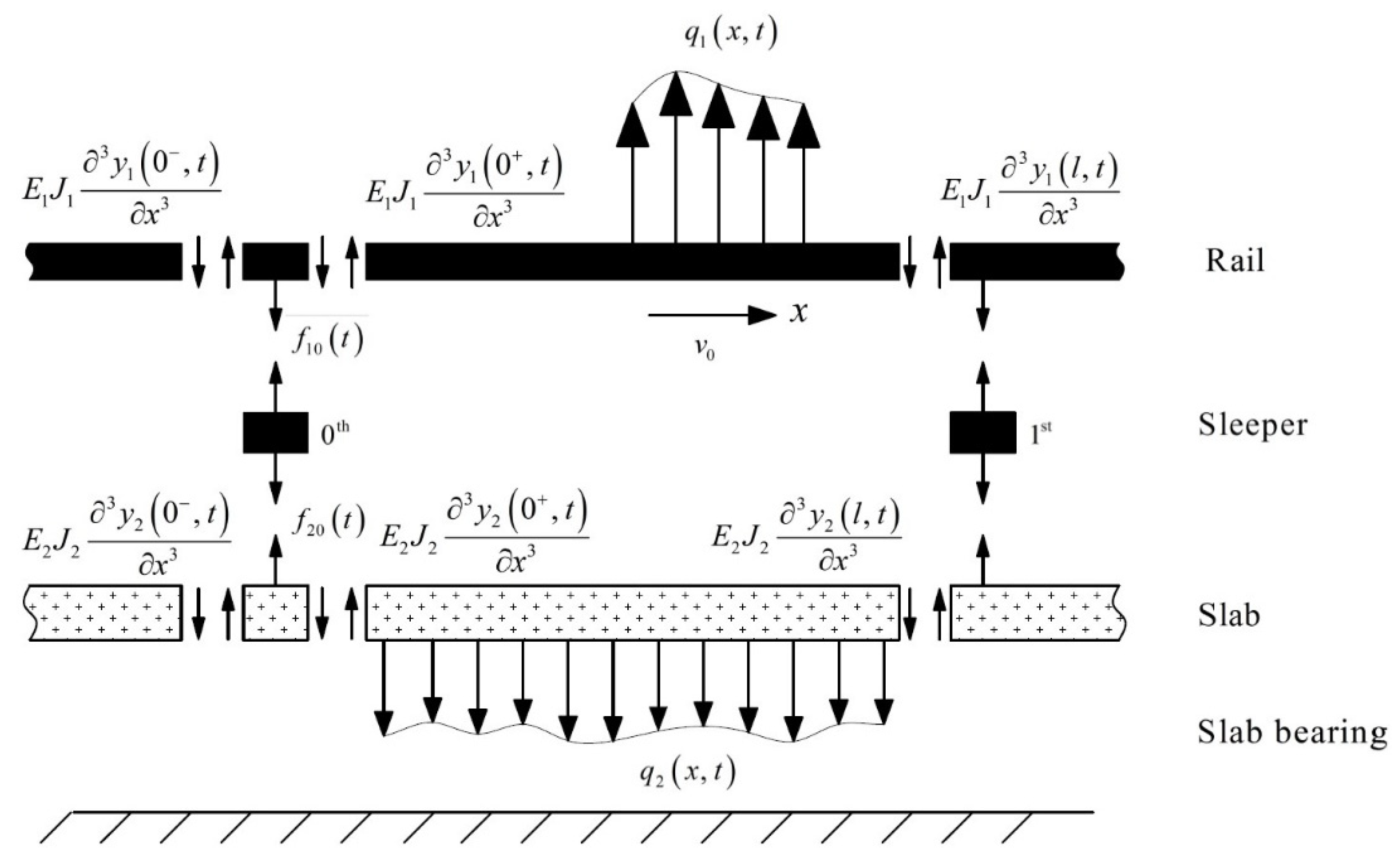

2. Description of the Whole Model

3. Double-Beam System with a Moving Harmonic Load

4. Interaction Between Wheel and Track

- (1)

- Calculate the displacement of the rail in frequency domain for a series of discretized in , for each ;

- (2)

- Obtain by selecting the value that corresponds to for each ;

- (3)

- Calculate by Simpson integration;

- (4)

- Calculate by Equation (48);

- (5)

- Calculate the dynamic response of this track-wheel system by the superposition of the response for each by Equation (49).

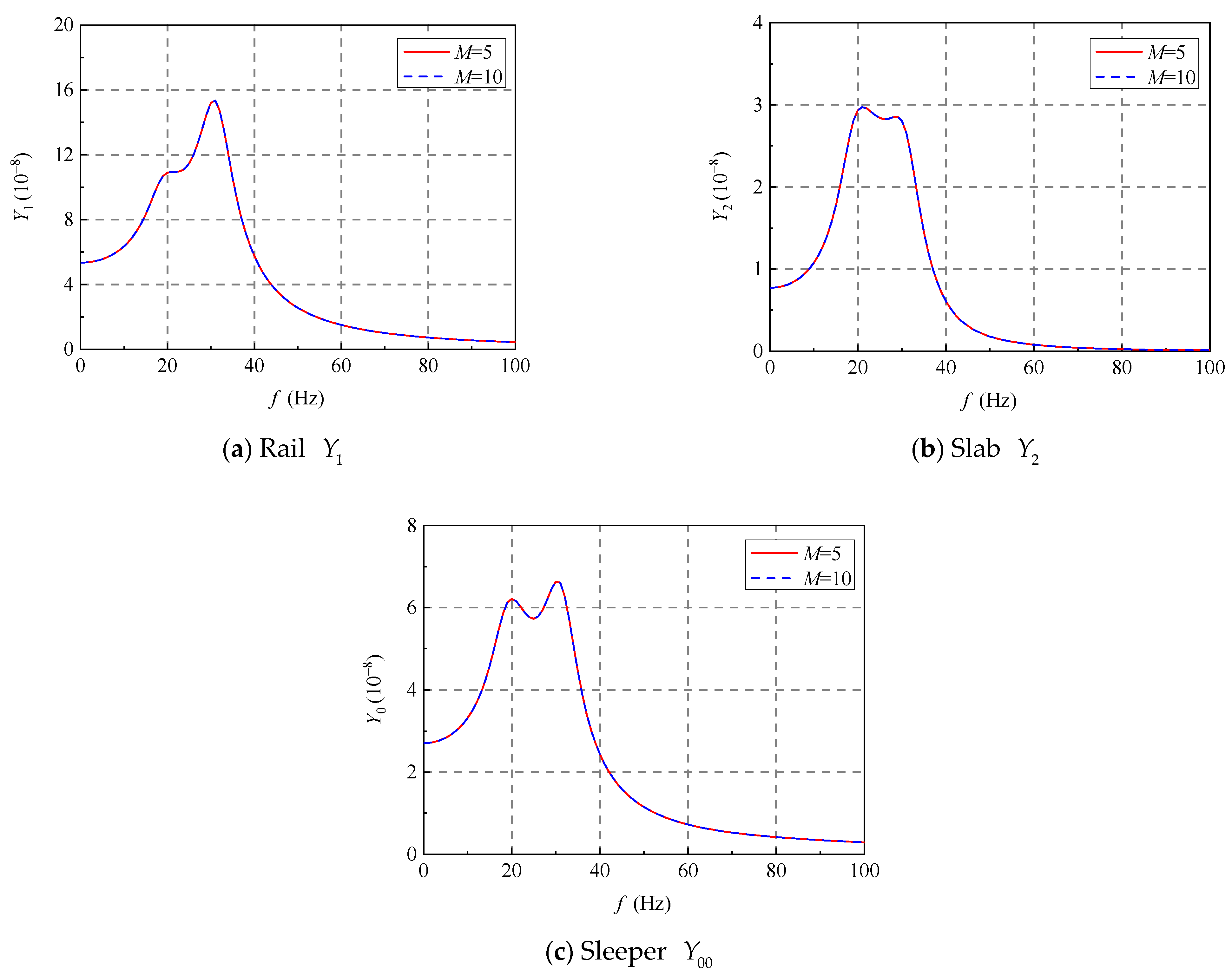

5. Numerical Results for Wheel–Track System

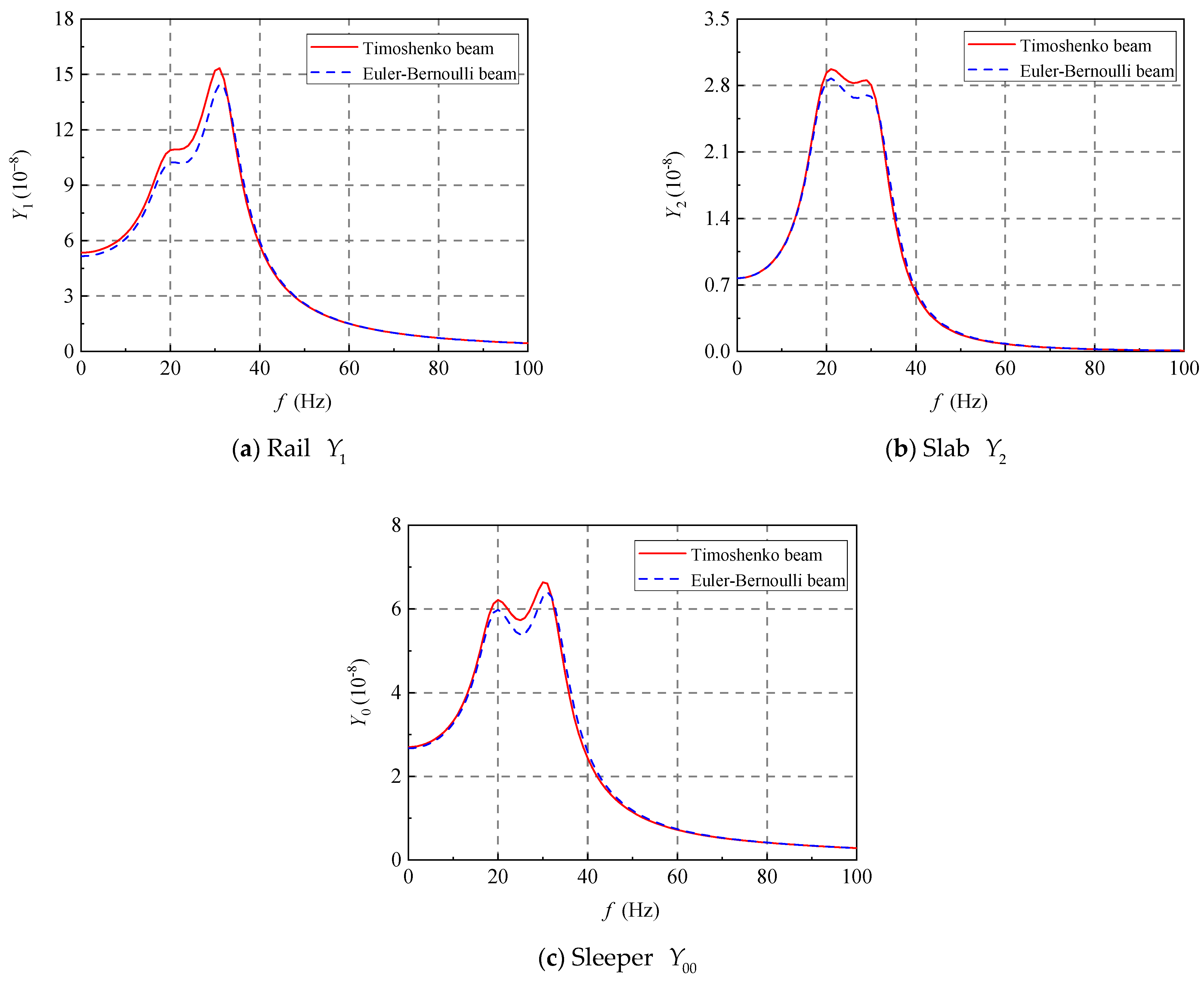

5.1. Comparison Between Timoshenko Beams and Euler–Bernoulli Beams

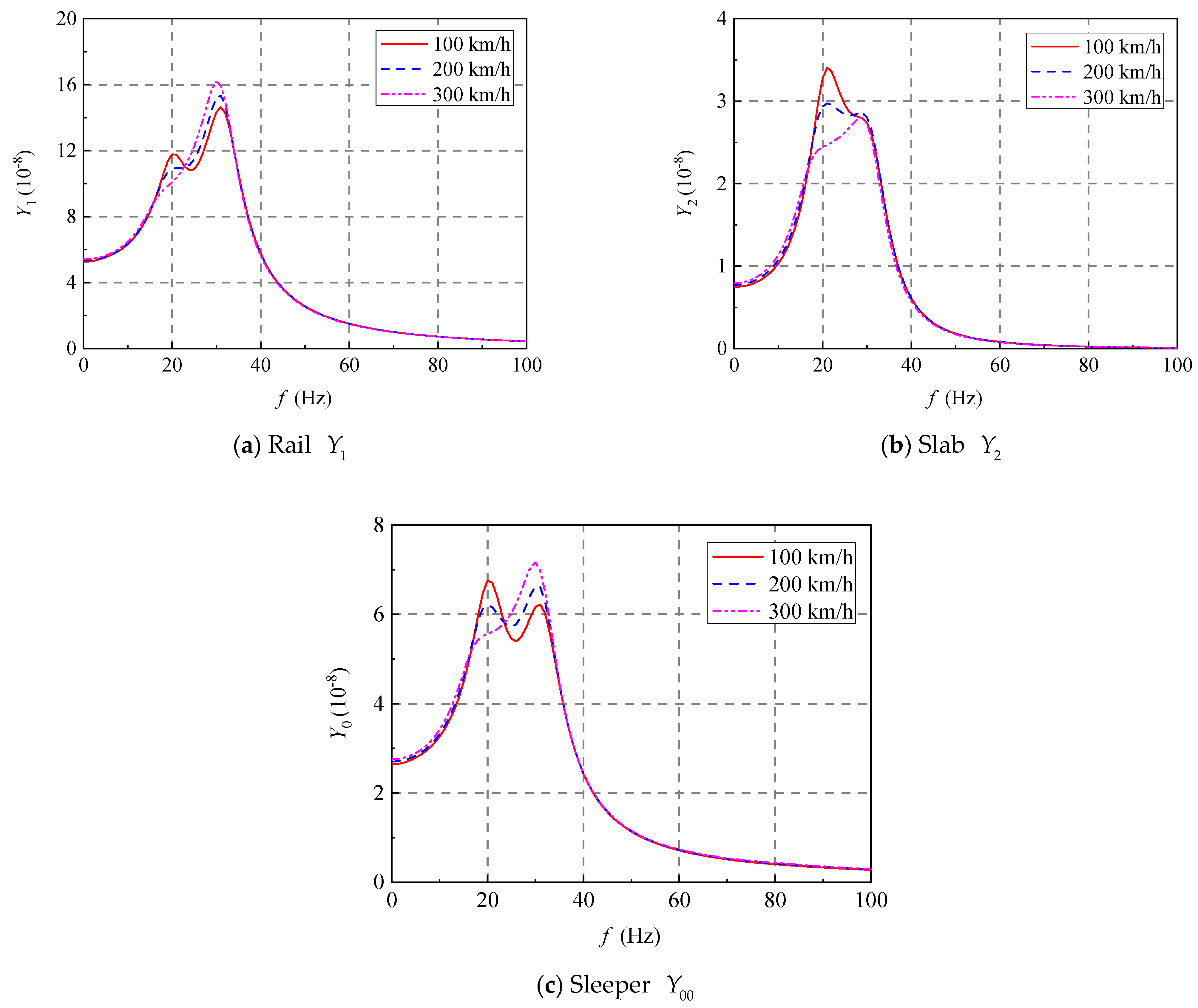

5.2. Effect of Load Velocity

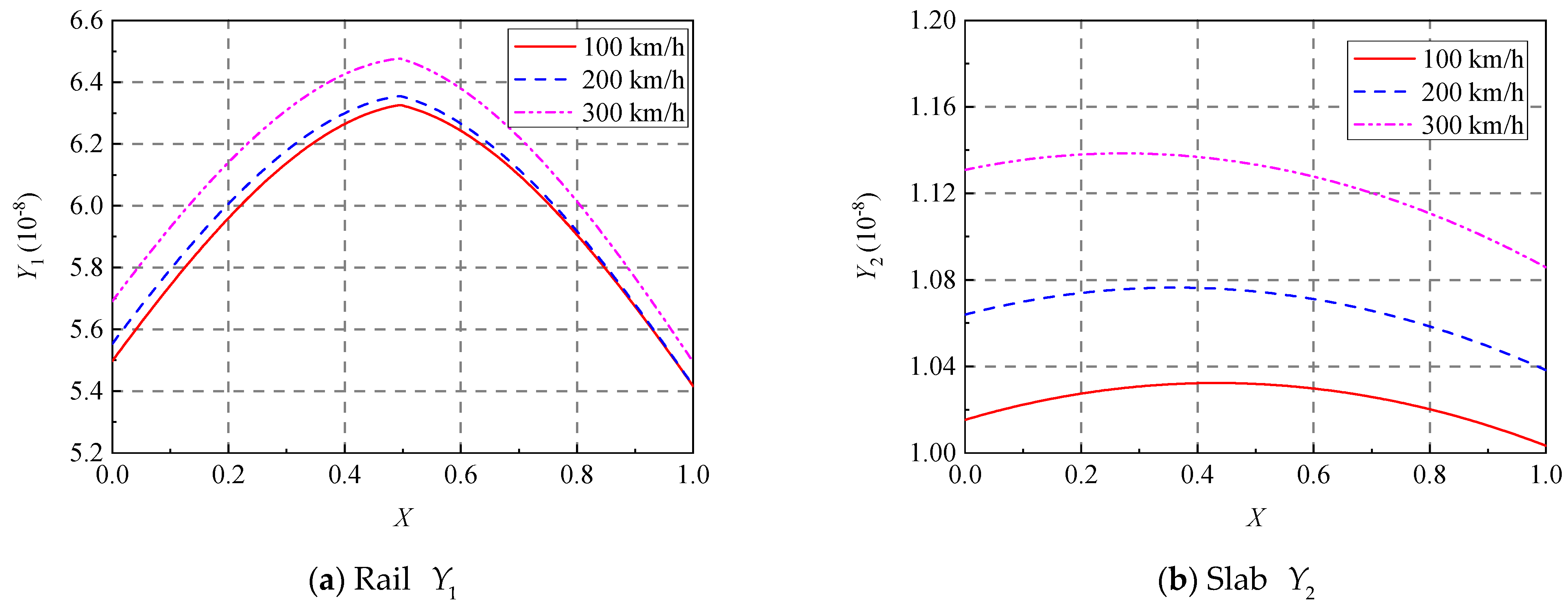

5.2.1. Vertical Displacements and Wheel–Track Interaction Force

5.2.2. Vertical Displacements and Wheel–Track Interaction Force

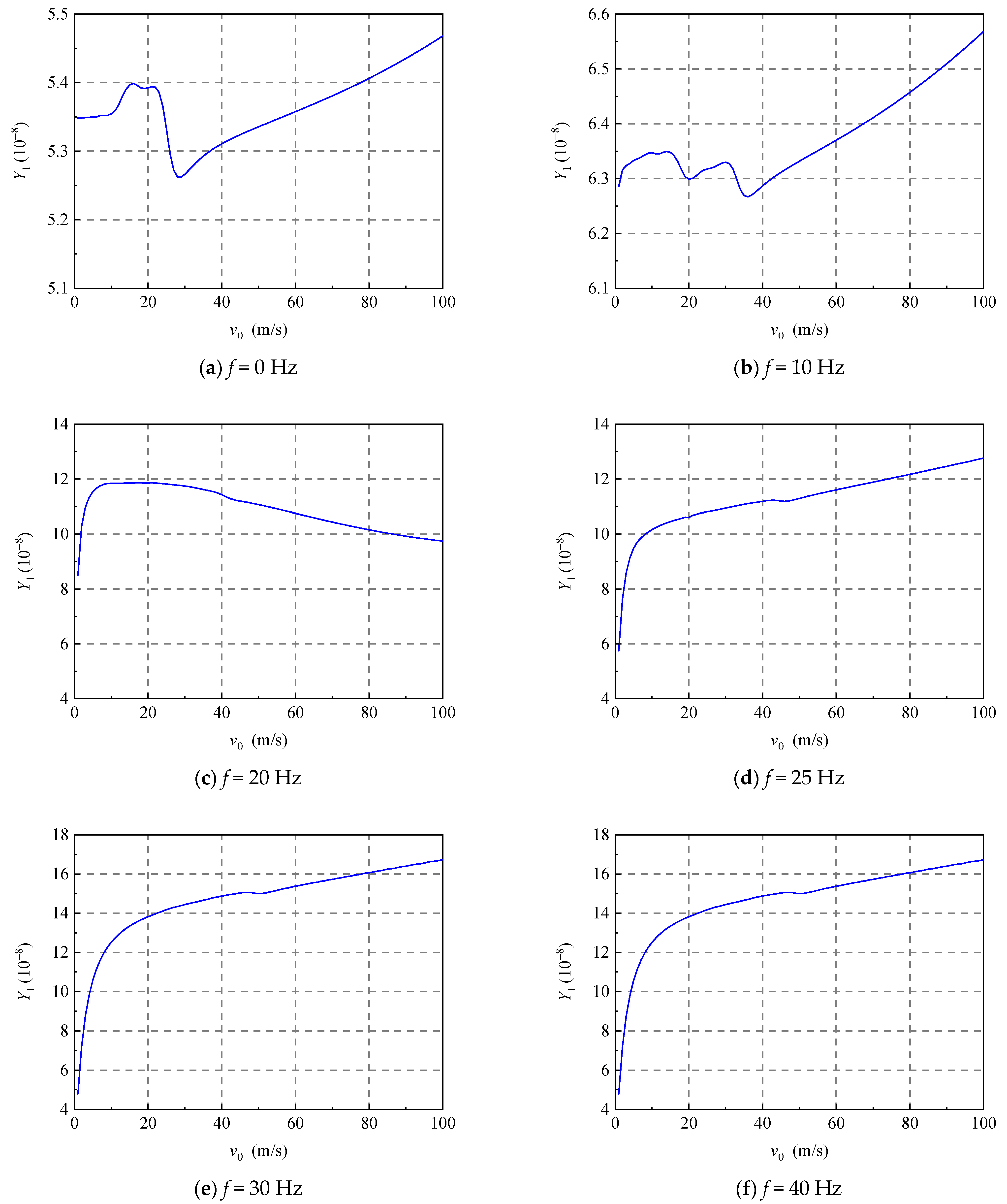

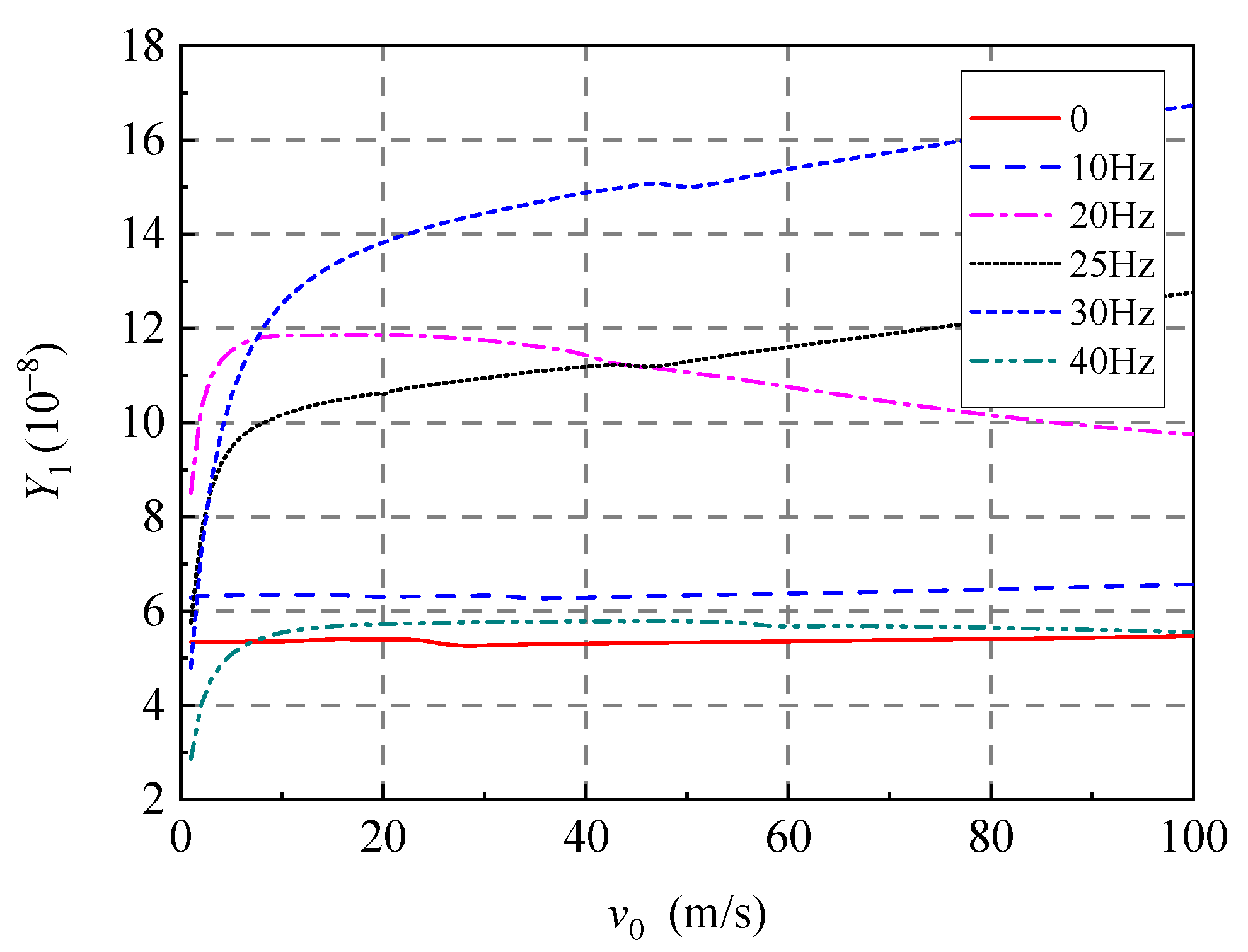

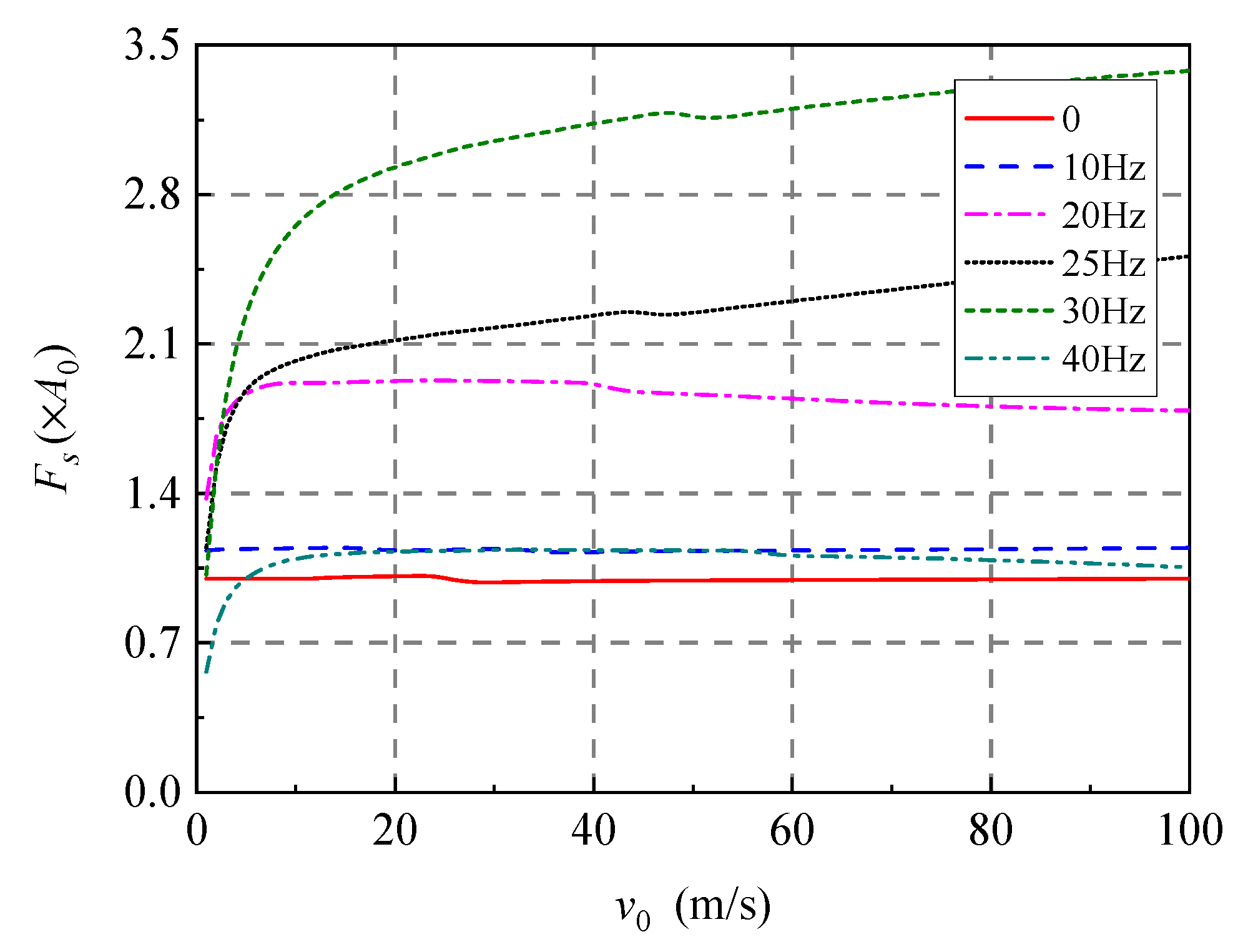

5.3. Effect of Load Frequency

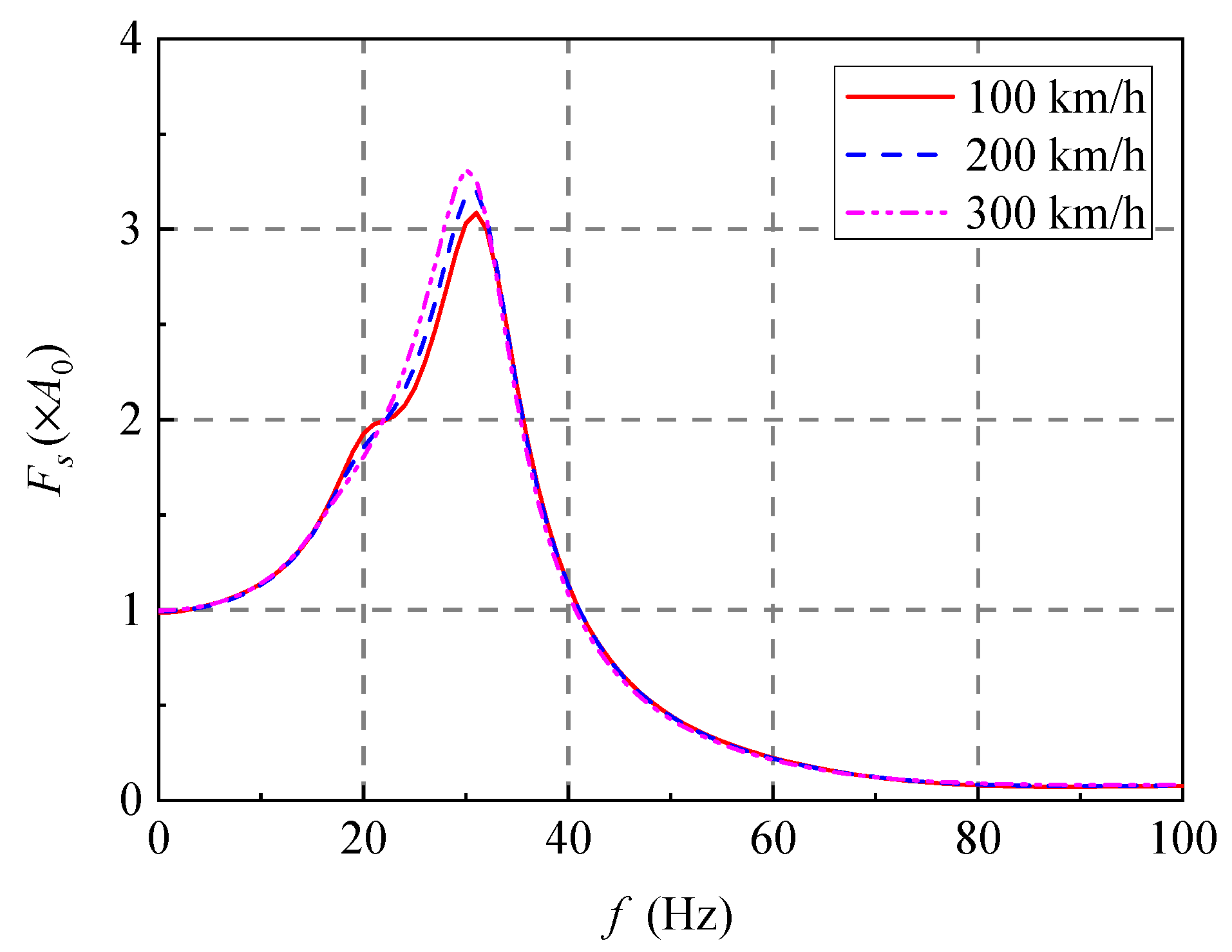

5.3.1. Vertical Displacements and Wheel–Track Interaction Force

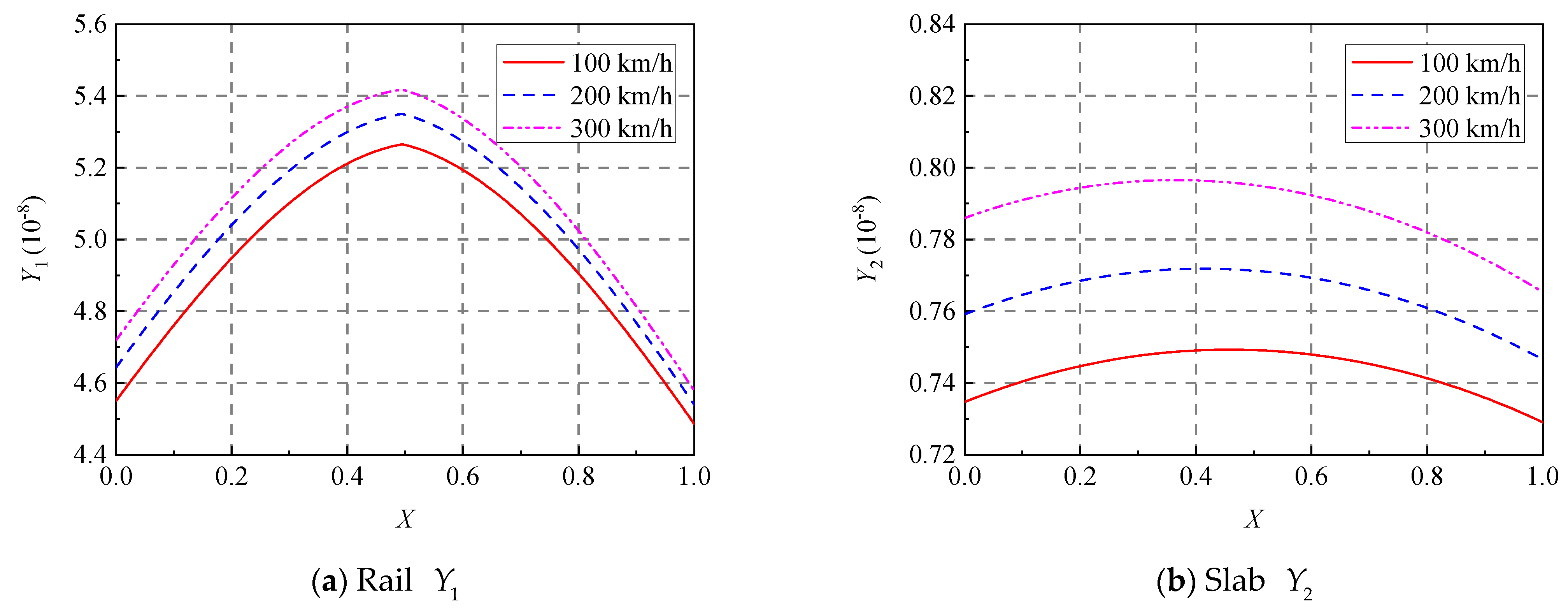

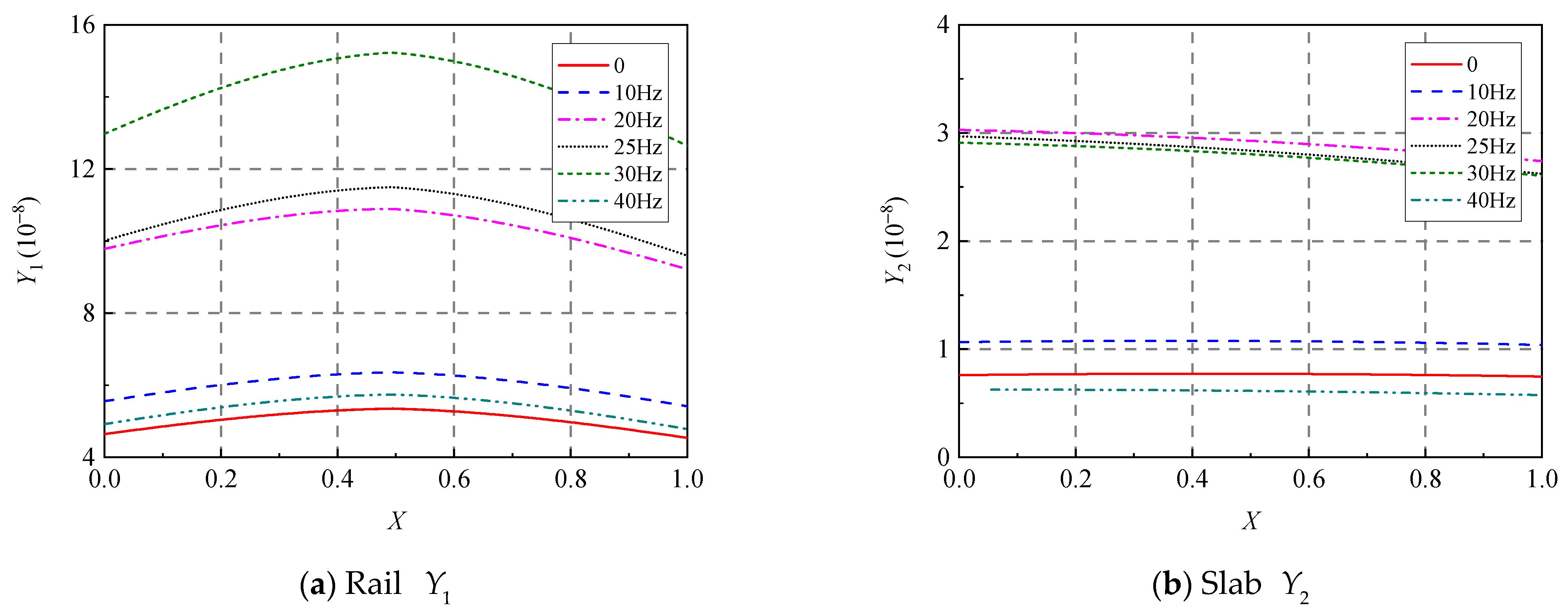

5.3.2. Deflections of the Rail and the Slab

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sheehan, J.P.; Debnath, L. On the dynamic response of an infinite Bernoulli-Euler beam. Pure Appl. Geophys. 1972, 97, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. A closed-form solution of a Bernoulli-Euler beam on a viscoelastic foundation under harmonic line loads. J. Sound Vib. 2001, 242, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. On dynamic analysis method for large-scale train-track-substructure interaction. Railw. Eng. Sci. 2022, 30, 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. An explicit representation of steady state response of a beam on an elastic foundation to moving harmonic line loads. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2003, 27, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulu, G.B.; Chen, R.; Wang, P.; Xu, J.M.; Chen, J.Y. Effect of polygonal wheel on the vehicle-track dynamic interaction in turnout and its transmission to the trailer bogie wheels. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2024, 62, 1713–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.; Nielsen, S.R.K. Vibrations of a track caused by variation of the foundation stiffness. Probabilistic Eng. Mech. 2003, 18, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, A.K.; Chandra, S.; Singh, A.B. Steady-state response of an elastically supported infinite beam to a moving load. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 291, 1148–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechitailo, N.V.; Lewis, K.B. Critical velocity for rails in hypervelocity launchers. J. Impact Eng. 2006, 33, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroma, S.G.; Hussein, M.F.M.; Owen, J.S. Vibration of a beam on continuous elastic foundation with nonhomogeneous stiffness and damping under a harmonically excited mass. J. Sound Vib. 2004, 333, 2571–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrovová, Z. A general procedure for the dynamic analysis of finite and infinite beams on piece-wise homogeneous foundation under moving loads. J. Sound Vib. 2010, 329, 2635–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, J.A.; Hunt, H.E.M. Ground vibration generated by trains in underground tunnels. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 294, 706–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.F.M.; Hunt, H.E.M. A power flow method for evaluating vibration from underground railways. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 293, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordan, P.; Mihaela, S.Q.; Marian, S.R. Dynamic Behavior of Railway Bridges Under High-Speed Traffic Loads. Rom. J. Transp. Infrastruct. 2024, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, L.; Deng, X.Y. An improved method for slab track-soil interaction considering soil surface deformation. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 2024, 52, 4260–4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Jones, C.J.C.; Thompson, D.J. A theoretical study on the influence of the track on train-induced ground vibration. J. Sound Vib. 2004, 272, 909–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlström, A.; Boström, A. Efficiency of trenches along railways for trains moving at sub- or supersonic speeds. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2007, 27, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, N.G. Considerations on second order beam theories. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1981, 17, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreles, M.A.; Botello, S.; Salinas, R. A root-finding technique to compute eigenfrequencies for elastic beams. J. Sound Vib. 2005, 284, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruge, P.; Birk, C. A comparison of infinite Timoshenko and Euler-Bernoulli beam models on Winkler foundation in the frequency- and time-domain. J. Sound Vib. 2007, 304, 932–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Huang, Y.H.; Shih, C.T. Response of an infinite Timoshenko beam on a viscoelastic foundation to a harmonic moving load. J. Sound Vib. 2001, 241, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, Q. Transient elastic wave propagation in an infinite Timoshenko beam on viscoelastic foundation. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2003, 40, 3211–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.O.M.; Zindeluk, M. Active control of waves in a Timoshenko beam. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2001, 38, 1749–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargarnovin, M.H.; Younesian, D.; Thompson, D.J.; Jones, C.J.C. Response of beams on nonlinear viscoelastic foundations to harmonic moving loads. Comput. Struct. 2005, 83, 1865–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, M. Non-linear vibration analysis of a functionally graded Timoshenko beam under action of a moving harmonic load. Compos. Struct. 2010, 92, 2532–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remington, P.J. Wheel/rail rolling noise—Part I: Theoretical analysis. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1987, 81, 1805–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, S. A linear wheel-track model to predict instability and short pitch corrugation. J. Sound Vib. 1999, 227, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempelmann, K.; Knothe, K. An extended linear model for the prediction of short-pitch corrugation. Wear 1996, 191, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belotserkovskii, P.M. The steady vibrations and resistance of a railway track to the uniform motion of an unbalanced wheel. J. Appl. Math. Mech. 2003, 67, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belotserkovskii, P.M. The interaction of an infinite wheel-train with a constant spacing between the wheels moving uniformly over a rail track. J. Appl. Math. Mech. 2004, 68, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.X.; Thompson, D.J. A double Timoshenko beam model for vertical vibration analysis of railway track at high frequencies. J. Sound Vib. 1999, 224, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.V.; Ordóñez, A.M.; Karnopp, B.H. Vibration of a double-beam system. J. Sound Vib. 2000, 229, 807–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Lu, Y.; Wang, S.L.; Liu, X. Vibration and buckling of a double-beam system under compressive axial loading. J. Sound Vib. 2008, 318, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, S.; Dang, J. Seismic damage prediction of RC buildings using machine learning. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 52, 3504–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridis, P.C.; Kavvadias, I.E.; Demertzis, K.; Iliadis, L.; Vasiliadis, L.K. Structural damage prediction of a reinforced concrete frame under single and multiple seismic events using machine learning algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, D.J. Vibration response and wave propagation in periodic structures. J. Eng. Ind. 1971, 93, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belotserkovskiy, P.M. On the oscillations of infinite periodic beams subjected to a moving concentrated force. J. Sound Vib. 1996, 193, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wheel: | |

| Mass of the wheel | |

| Constant velocity of the wheel | |

| Constant amplitude of the vertical concentrated force | |

| Angular frequency of the vertical concentrated force | |

| Rail: | |

| Young’s modulus of the rail | |

| Second moment of area of the rail cross-section | |

| Shear modulus of the rail | |

| Mass of the rail per unit length | |

| Cross-sectional area of the rail | |

| Shear force coefficient of the rail | |

| Sleeper: | |

| Sleeper spacing | |

| Concentrated mass of the sleeper | |

| Spring stiffness above and below the sleeper | |

| Damper viscosity above and below the sleeper | |

| Slab: | |

| Young’s modulus of the slab | |

| Second moment of area of the slab cross-section | |

| Shear modulus of the slab | |

| Mass of the slab per unit length | |

| Cross-sectional area of the slab | |

| Shear force coefficient of the slab | |

| Slab bearing: | |

| Spring stiffness of the slab bearing | |

| Damper viscosity of the slab bearing | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lu, M.; Wang, X.; Li, H. Dynamic Response of a Double-Beam System Subjected to a Harmonic Moving Load. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010514

Lu M, Wang X, Li H. Dynamic Response of a Double-Beam System Subjected to a Harmonic Moving Load. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):514. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010514

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Mingfei, Xuenan Wang, and Hui Li. 2026. "Dynamic Response of a Double-Beam System Subjected to a Harmonic Moving Load" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010514

APA StyleLu, M., Wang, X., & Li, H. (2026). Dynamic Response of a Double-Beam System Subjected to a Harmonic Moving Load. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010514