Optimization of AEBS for Heavy Goods Vehicles Incorporating Driver’s Control and 3D Visibility of Vulnerable Road Users

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Blind spots in any plane for HGVs: Develop a method to quantify driver blind spots and establish a 3D visibility evaluation function for external VRUs.

- (2)

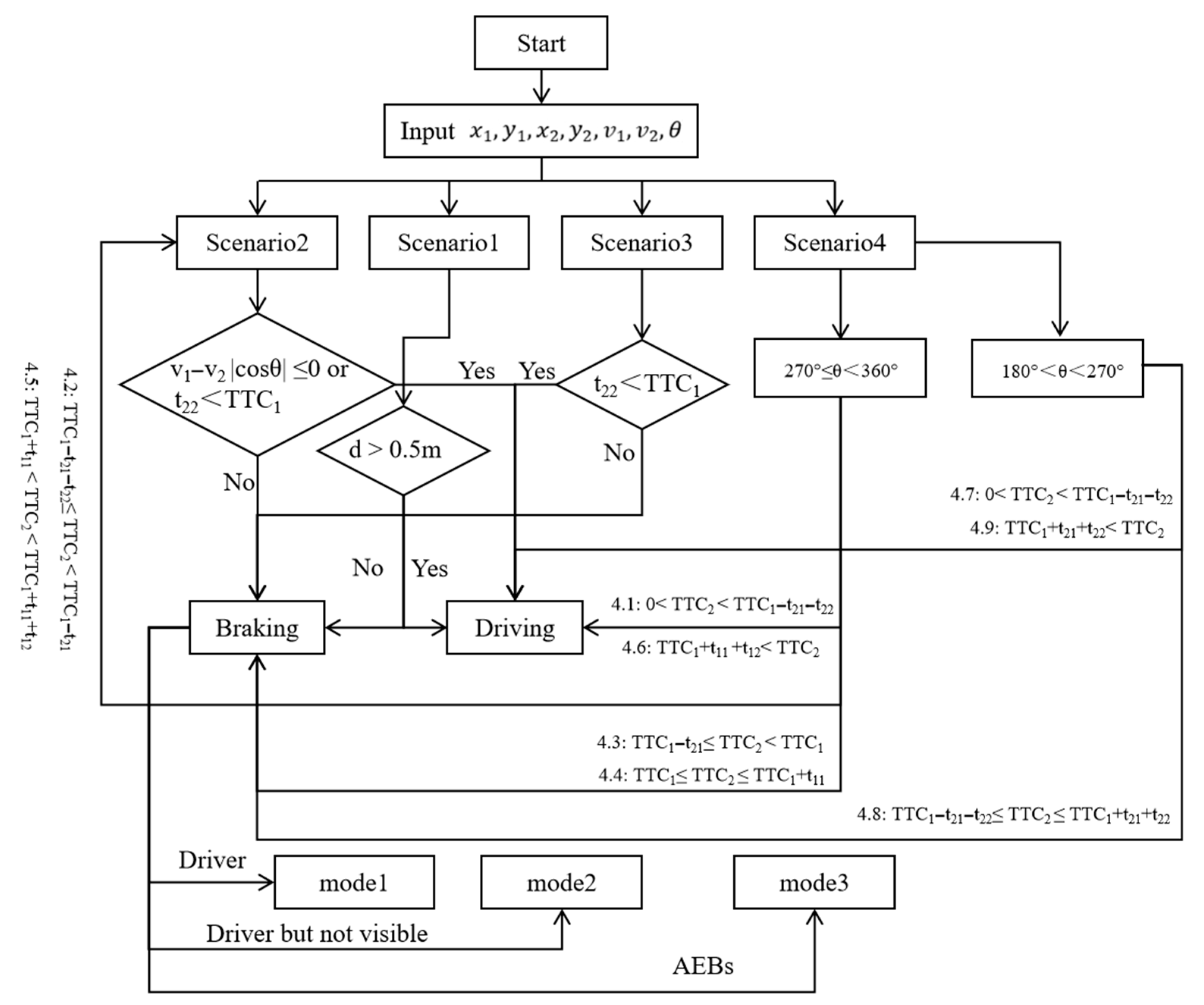

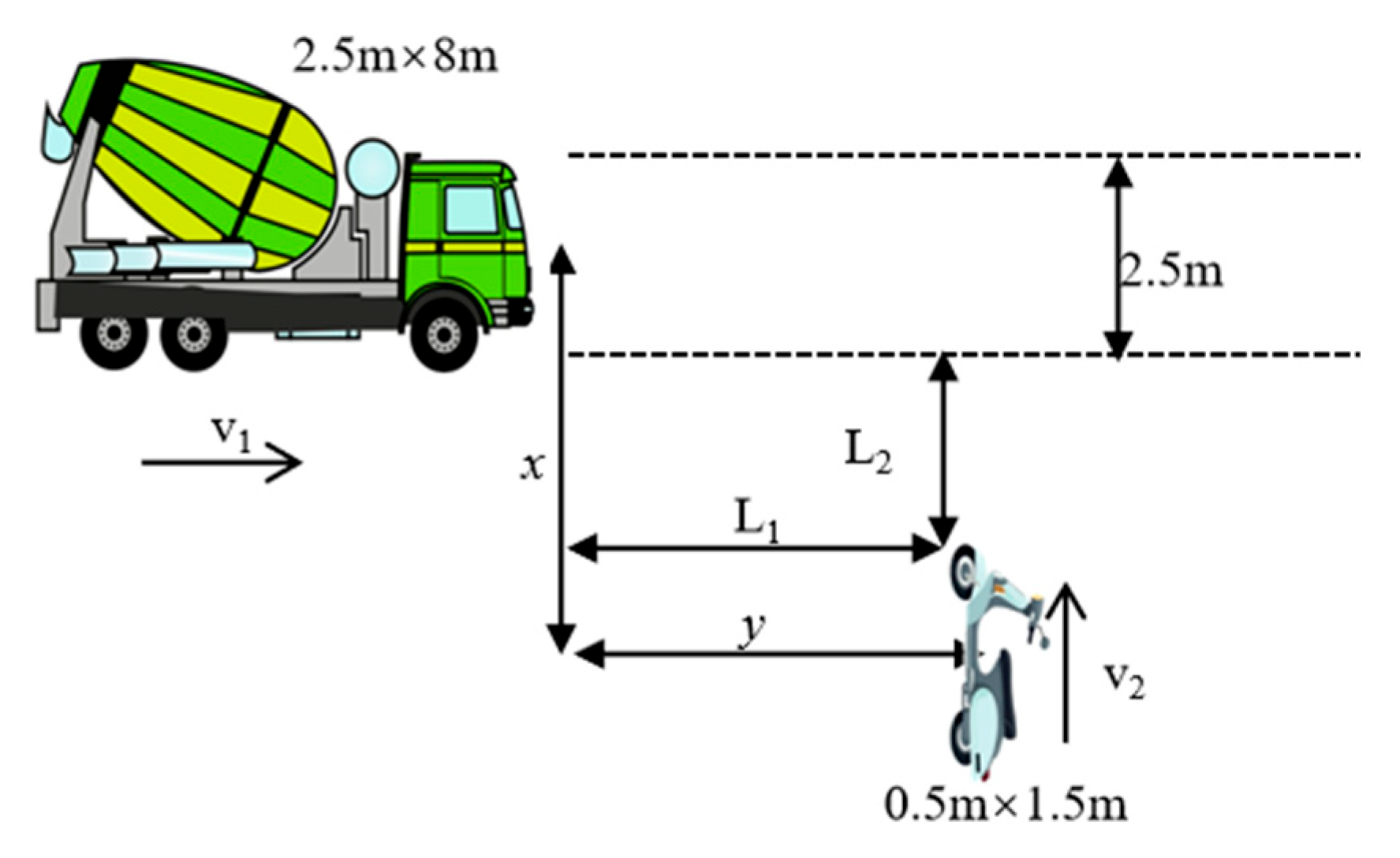

- Scenario modeling and 2D TTC: Analyze accident scenarios between HGVs and VRUs to summarize kinematic patterns, formalized as a scenario function. A novel 2D time to collision segmentation model is proposed based on the time difference for HGVs and VRUs to reach trajectory intersection points, serving as the braking trigger criterion (braking scenario function). Three braking modes are then introduced, incorporating VRU 3D visibility’s influence on driver response.

- (3)

- Integrated Driver-2D AEBS collision avoidance algorithm: Combine the visibility function, scenario function, braking scenario function, and braking modes into a unified algorithm that fuses driver intent and AEBS for VRU collision avoidance.

- (4)

- Model validation: Evaluate the proposed model under typical traffic conditions.

2. The Evaluation Function of 3D Visibility of VRUs

- (1)

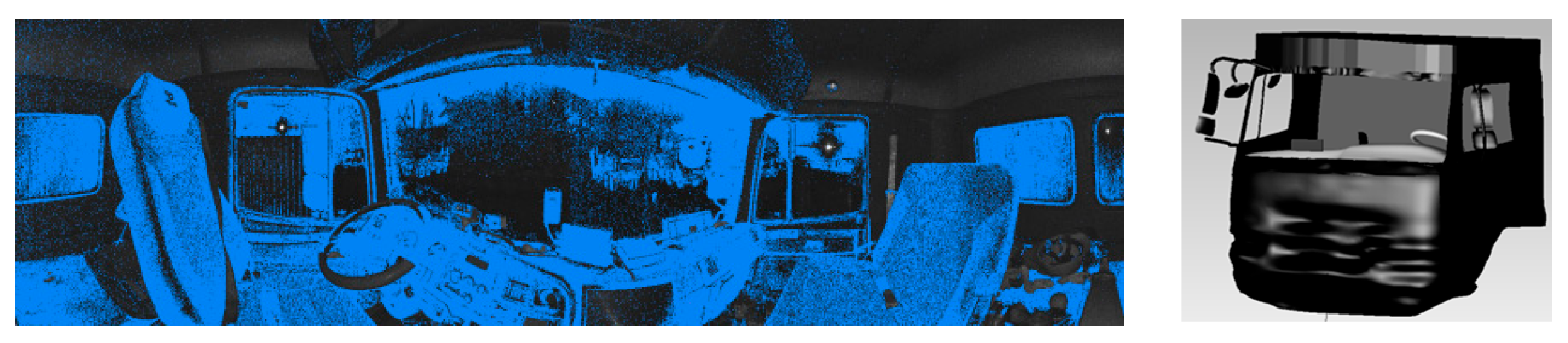

- Three-dimensional vehicle model construction: A prototype left-hand drive vehicle was selected, with fiducial targets deployed on the left, front, and right cabin surfaces as calibration benchmarks. Following laser scanner positioning and calibration—including instrument leveling and positional alignment—millimeter-level ranging resolution was set to optimize structural detail capture and processing efficiency. Three-dimensional point cloud data of internal and external cabin structures was subsequently acquired through laser scanning. Post-processing reconstructed the vehicle’s geometric profile as depicted in Figure 1, incorporating cutouts for side windows and the windshield while retaining the following sightline-critical cabin components: steering wheel, instrument panel, and OEM-installed displays.

- (2)

- Defining the geometric coordinate system: The vehicle model was imported into TracePro70 software, where a right-handed Cartesian coordinate system was established with its origin at the ground projection of the center point of the vehicle’s foremost front edge. The X-axis aligned with the front edge (positive direction toward the right-hand side), the Y-axis followed the vehicle centerline (positive direction forward along the travel path), and the Z-axis extended vertically upward, while the ground reference plane was defined at z = 0 mm.

- (3)

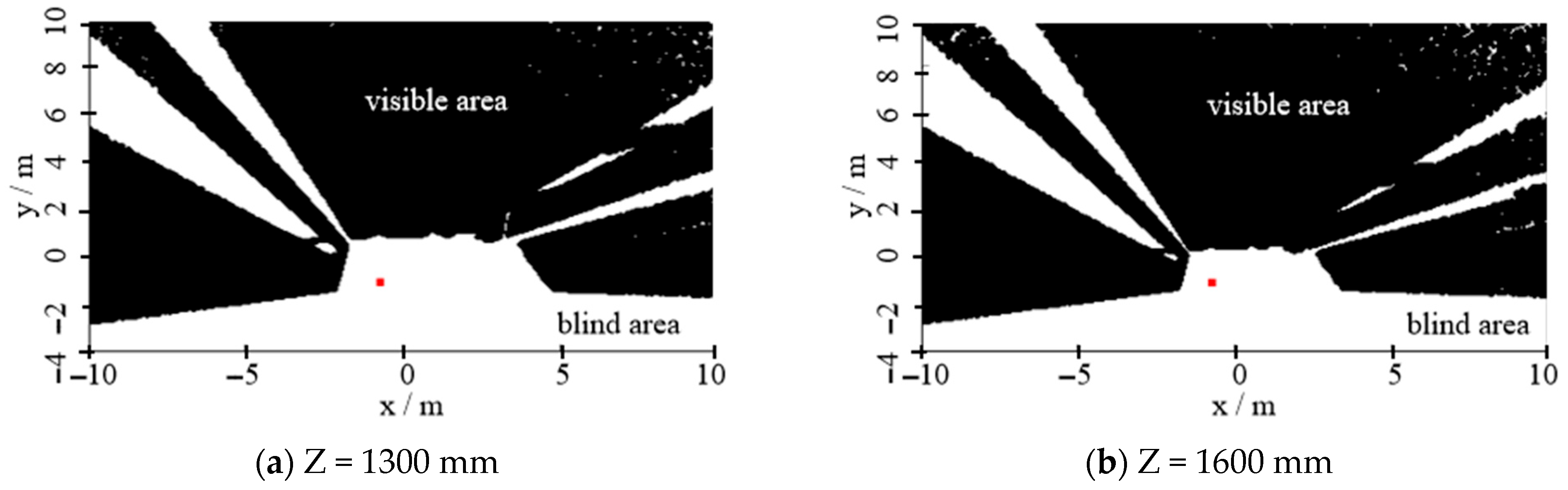

- Eyepoint configuration: Based on the Seating Reference Point—a fundamental vehicle design attribute defined during initial development—the center of the driver’s eyellipse was determined and marked to establish the eyepoint coordinates. In accordance with the Society of Automotive Engineers Standard [29], the 99th percentile eyellipse was adopted, with the eyepoint positioned at (700 mm, −1140 mm, 2550 mm) (As shown by the red dot in Figure 2). A 4 million ray source was then set at the eyepoint to simulate the driver’s line of sight, with ray count optimized to balance computational efficiency and ray distribution density (at least one ray of light in each 20 mm × 20 mm grid under unobstructed conditions). Rays were emitted omnidirectionally from the source.

- (4)

- Vehicle surface material configuration: All vehicle surfaces were assigned optically pure absorptive properties with zero reflectance and zero transmittance, ensuring the complete absorption of incident rays upon surface contact.

- (5)

- Data recording: Spatial coordinates and direction vectors of rays escaping the cabin were systematically recorded and archived.

- (6)

- Data processing: The escaped rays underwent computational processing to reconstruct the three-dimensional driver visibility volume.

3. Two-Dimensional Collision Algorithm Considering 3D Visibility of VRU

3.1. The Classification Function of Driving Scenarios

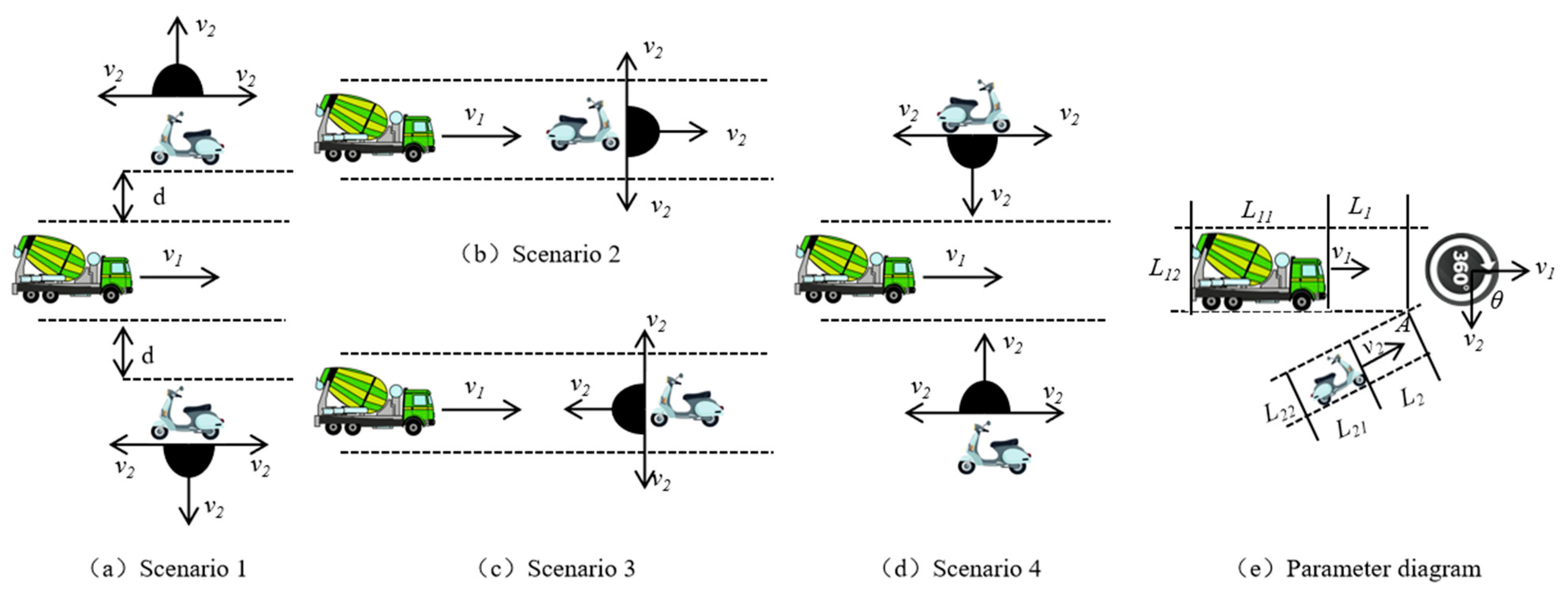

- (1)

- Scenario 1: Non-intersecting trajectories, VRU is on HGV’s right with 0°≤ θ ≤180° or VRU on HGV’s left with 180° ≤ θ ≤ 360°.

- (2)

- Scenario 2: Imminent collision, trajectories intersect and VRU is on HGV’s trajectory with 0° ≤ θ ≤ 90° or 270° ≤ θ ≤ 360°.

- (3)

- Scenario 3: Imminent collision, trajectories intersect and VRU is on HGV’s trajectory with 90° < θ < 270°.

- (4)

- Scenario 4: Imminent collision, potential conflict-non-aligned paths, trajectories intersect but VRU not on trajectory contour, VRU is on HGV’s right with 180° < θ < 360°, or VRU is on HGV’s left with 0° < θ < 180°.

3.2. The Extraction Function of 2D Collision Avoidance Scenario

3.3. The Braking Function of HGVs Under Different Control Modes

3.4. The Driver-2D AEBS Algorithm Considering 3D Visibility

4. Algorithm Validation and Analysis

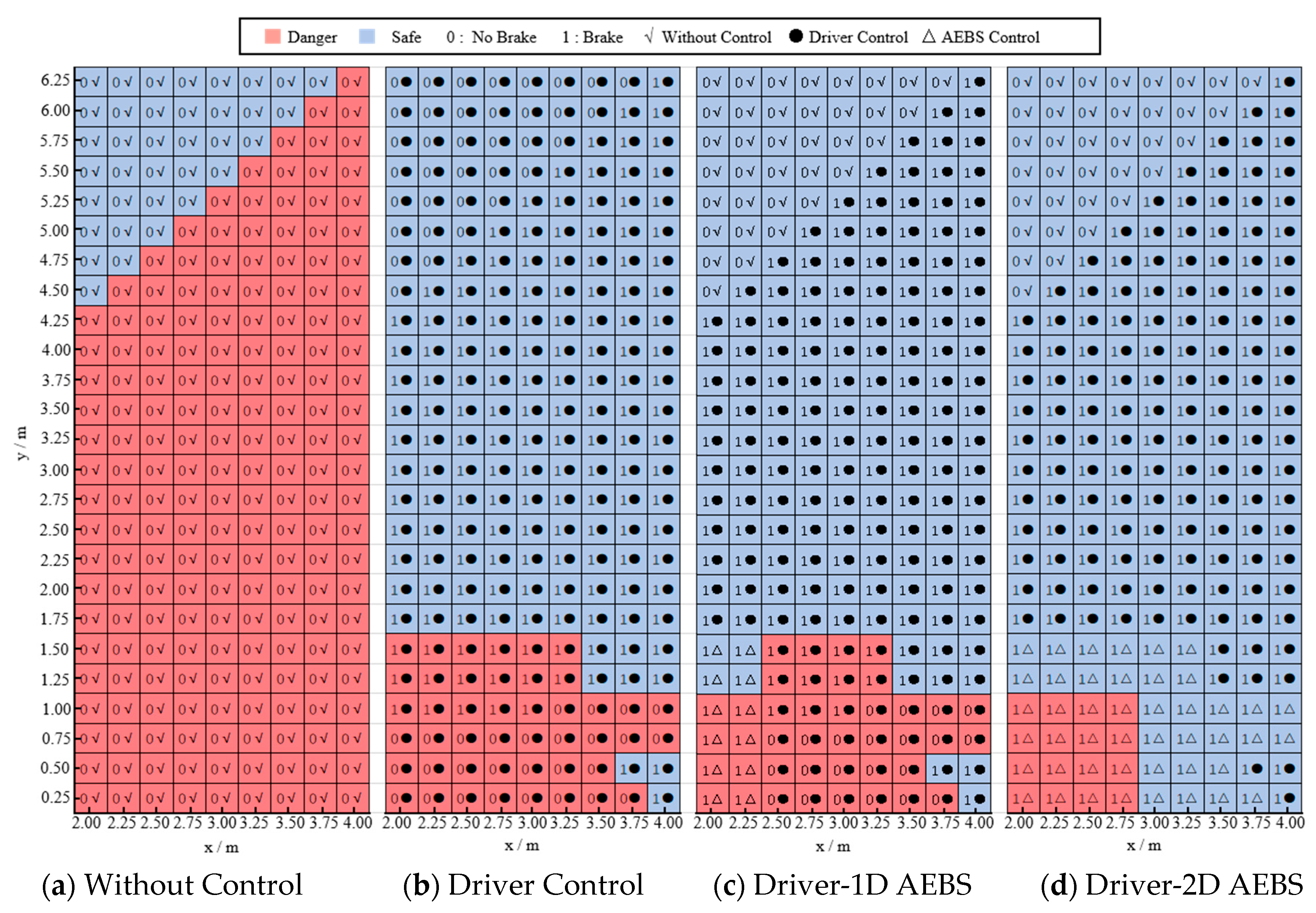

4.1. The Influence of the VRU’s Position

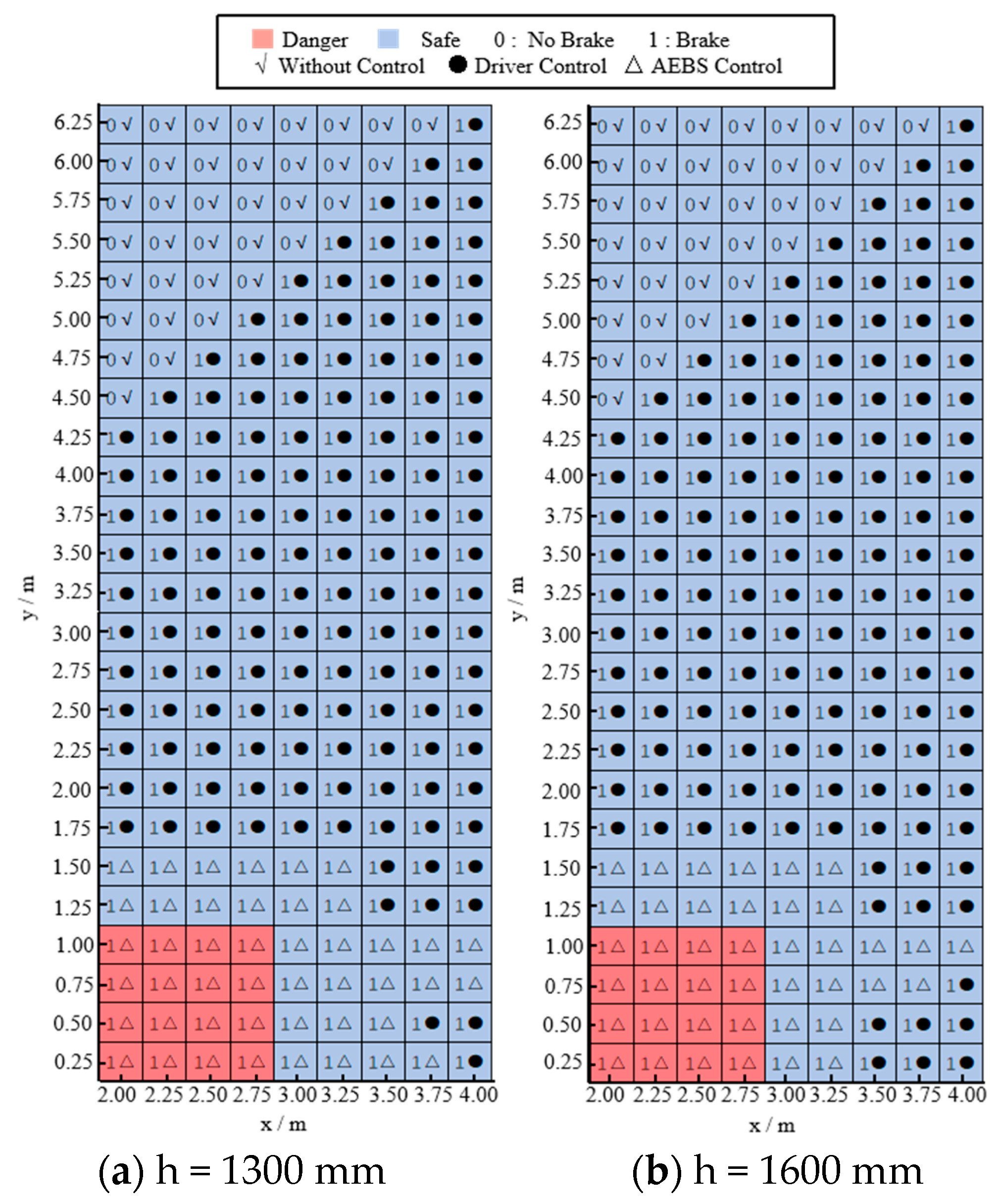

4.2. The Influence of the VRU’s Height

4.3. The Influence of the VRU’s Speed

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- (1)

- With the vision space, it is faster and easier to estimate the visibility of VRUs with any heights: The visibility of a VRU influences driving maneuvers (for instance, the brake) directly. In the proposed method, the 3D vision space of an HGV was first built up. Compared with the past blind spots on the ground plane, the vision space provides an accurate and practical basis for dealing with the blind spot risks. The vision space was transferred into the visibility function included in the Driver-2D AEBS.

- (2)

- The proposed Driver-2D AEBS is designed to address blind spots and 2D collision risks while avoiding excessive intervention: Based on the accident video data, a motion state scenario classification function for HGVs and VRUs was established. With the function, the driving status can be divided into four types. With the scenario classification function and 2D TTC model, the braking scenario extraction function was derived which can directly identify braking-required scenarios. The AEBS control strategy improved the adaptability to the working conditions and braking decision-making rationality. This exceeds the capability of fixed-width lateral triggering AEBS. In addition, three braking modes were included in the algorithm, incorporating the VRU visibility’s influence on driver response.

- (3)

- The validation results show that the proposed algorithm can significantly reduce collision risk zones while overcoming the limitations of conventional 1D TTC models that focus solely on longitudinal risks. By hybridizing driver control and 2D AEBS control, the system leverages the driver’s braking capability while utilizing AEBS as a safety-critical fallback, thereby preventing unnecessary braking interventions. For the AEBS integrated with 2D TTC, collisions can be prevented except in extreme cases. In such extreme cases, the collision speed is reduced by approximately 50%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2023; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Azizbek, M.; Dilnoza, B.; Sarvarbek, A. Causes of traffic accidents and measures to prevent them. Educ. Sci. Innov. Ideas World 2024, 37, 61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Afiqah, O.; Fauziana, L. Examining fatal motorcycle crashes in malaysia: Rider age, road attributes and collision partner dynamics. Int. J. Latest Technol. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. 2025, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blower, D.F. The Large Truck Crash Causation Study; UMTRI-2002-31; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Viadero-Monasterio, F.; Alonso-Rentería, L.; Pérez-Oria, J.; Viadero-Rueda, F. Radar-based pedestrian and vehicle detection and identification for driving assistance. Vehicles 2024, 6, 1185–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, H.; Umeda, M. Performance of AEB systems in preventing car-pedestrian collisions. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2025, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, X.; Glaser, Y.; Wu, X.; Xu, X. Developing an improved automatic preventive braking system based on safety-critical car-following events from naturalistic driving study data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 178, 106834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Yang, Y.; Wu, G.; Zhao, X.; Fang, S.; Liao, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, M. A systematic review of autonomous emergency braking system: Impact factor, technology, and performance evaluation. J. Adv. Transp. 2022, 2022, 1188089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Yin, X.; Liu, P.; Hou, Z.; Zhao, D. Study on the control algorithm of automatic emergency braking system (AEBS) for commercial vehicle based on identification of driving condition. Machines 2022, 10, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, P.; Song, B.; Hedrick, J.K. Development of a collision avoidance system. SAE Trans. 1998, 1, 1334–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; Chang, S.; Jiang, L.; Li, X. Research on regenerative brake technology of electric vehicle based on direct-drive electric-hydraulic brake system. Int. J. Veh. Des. 2016, 70, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lv, Z.; Liu, X. Algorithm and simulation verification of longitudinal collision avoidance for autonomous emergency break system based on PreScan. J. Automot. Saf. Energy 2017, 8, 136–143. [Google Scholar]

- Roșu, I.-A.; Carabulea, L.; Buzdugan, I.-D.; Antonya, C. Time-to-collision for the pedestrian protection system simulation. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 74, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viadero-Monasterio, F.; Meléndez-Useros, M.; Jiménez-Salas, M.; Boada, B.L. Robust adaptive control of heterogeneous vehicle platoons in the presence of network disconnections with a novel string stability guarantee. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2025, 11, 3578936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, S.; Graham, R. The format and presentation of collision warnings. In Ergonomics and Safety of Intelligent Driver Interfaces; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Kodaka, K.; Li, K. Crash probability estimation via quantifying driver hazard perception. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 116, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hu, L.; Peng, Y.; Wu, X.; Xiang, G.; Xu, Q. Research on drivers’ hazard perception before vehicle-to-powered two-wheeler crashes. Automot. Eng. 2024, 46, 498–509. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.; Morris, A. Quantifying accident risk and severity due to speed from the reaction point to the critical conflict in fatal motorcycle accidents. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 141, 105548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, J.; Yan, X.; Li, X.; Duan, K.; Yang, J.; Xue, Q. An improved automated braking system for rear-end collisions: A study based on a driving simulator experiment. J. Saf. Res. 2022, 80, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuwian, T.; Saeed, R.B.; Amin, A.A. Autonomous vehicle with emergency braking algorithm based on multi-sensor fusion and super twisting speed controller. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Jin, S. Optimization of AEB system for vertical driving condition of vehicle and two-wheeler intersection. J. Saf. Environ. 2023, 06, 1916–1925. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Y. Study on pre-crash scenarios and AEB optimization between vehicle and two-wheeler. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2022, 49, 501–509. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Xiang, G.; Deng, H.; Jiang, Z.; Peng, Y. Research on drivers’ hazard perception and visual characteristics before vehicle-to-powered two-wheeler collisions. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2025, 114, 575–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.J.; Lee, M.S.; Kang, N. Partial and full braking algorithm according to time-to-collision for both safety and ride comfort in an autonomous vehicle. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2020, 21, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teizer, J.; Allread, B.S.; Mantripragada, U. Automating the blind spot measurement of construction equipment. Autom. Constr. 2010, 19, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larue, C.; Giguère, D. Measurement and evaluation of blind spots in trucks—Rear view of vehicles. IRSST 1992, 5, 2404. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, Y.; Oikawa, S. Effect of A-Pillar Blind Spots on a Driver’s Pedestrian Visibility during Vehicle Turns at an Intersection. Stapp Car Crash J. 2024, 68, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 5006; Earth-Moving Machinery-Operator’s Field of View-Test Method and Performance Criteria. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Moore, A.; Yuan, J.; Ou, S.; Torres, J.R.; Sujan, V.; Siekmann, A. Key considerations in assessing the safety and performance of camera-based mirror systems. Safety 2023, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclaughlin, S.B. Analytic Assessment of Collision Avoidance Systems and Driver Dynamic Performance in Rear-End Crashes and Near-Crashes. 2007. Available online: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu (accessed on 30 October 2007).

- Viadero-Monasterio, F.; Gutiérrez-Moizant, R.; Meléndez-Useros, M.; López Boada, M.J. Static output feedback control for vehicle platoons with robustness to mass uncertainty. Electronics 2024, 14, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scenario | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | Maintain a lateral safety distance to avoid collision. | |

| Scenario 2 | If v1 − v2 |cosθ| ≤ 0 or t22 < TTC1, safe without braking, fbrake = 0. Otherwise, collision risk exists at current speed, fbrake = 1. | |

| Scenario 3 | If t22 < TTC1, safe without braking, fbrake = 0. If TTC1 < t22, collision risk exists at current speed, fbrake = 1. | |

| Scenario 4 (Symmetric for left/right VRU; illustrated for right side: 180° < θ < 360°) | Sub-scenario 4.1 | If 270° ≤ θ < 360° and 0 < TTC2 < TTC1 − t21 − t22, VRU will reach the edge of the predicted collision zone first, and VRU has enough time to cross the predicted collision zone, fbrake = 0. |

| Sub-scenario 4.2 | If 270° ≤ θ < 360° and TTC1 − t21 − t22 ≤ TTC2 < TTC1 − t21, VRU will reach the edge of the predicted collision zone first. It is necessary to estimate the fbrake according to the Scenario2 after VRU reaches the edge of the predicted collision zone (TTC2 ≤ t < TTC1 − t21). | |

| Sub-scenario 4.3 | If 270° ≤ θ < 360° and TTC1 − t21 ≤ TTC2 < TTC1, VRU will reach the edge of the predicted collision zone first. Collision risk exists at current speed, fbrake = 1. | |

| Sub-scenario 4.4 | If 270° ≤ θ < 360° and TTC1 ≤ TTC2 ≤ TTC1 + t11, HGV will reach the edge of the predicted collision zone first. Collision risk exists at current speed, fbrake = 1. | |

| Sub-scenario 4.5 | If 270° ≤ θ < 360° and TTC1 + t11 < TTC2 < TTC1 + t11 + t12, HGV will reach the edge of the predicted collision zone first. It is necessary to estimate the fbrake according to the Scenario2 after HGV reaches the edge of the predicted collision zone (TTC2 ≤ t < TTC1 + t11 + t12). | |

| Sub-scenario 4.6 | If 270° ≤ θ < 360° and TTC1 + t11 + t12 < TTC2, HGV will reach the edge of the predicted collision zone first, and HGV has enough time to cross the predicted collision zone, fbrake = 0. | |

| Sub-scenario 4.7 | If 180° ≤ θ < 270° and 0 < TTC2 < TTC1 − t21 − t22, VRU will reach the edge of the predicted collision zone first, and VRU has enough time to cross the predicted collision zone, fbrake = 0. | |

| Sub-scenario 4.8 | If 180° ≤ θ < 270° and TTC1 − t21 − t22 ≤ TTC2 ≤ TTC1 + t21 + t22. Collision risk exists at current speed, fbrake = 1. | |

| Sub-scenario 4.9 | If 180° ≤ θ < 270° and TTC1 + t21 + t22 < TTC2, and HGV has enough time to cross the predicted collision zone, fbrake = 0. | |

| x/m | y/m | fvisibility | fscenario | Without Control | Driver Control | Driver-1D AEBS | Driver-2D AEBS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fbrake | vcollision/(m/s) | fbrake | vcollision/(m/s) | fbrake | vcollision/(m/s) | fmode | vcollision/(m/s) | ||||

| 3.00 | 0.25 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | Smode3 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 0.50 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | Smode3 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 0.75 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | Smode3 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 1.00 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.80 | 1 | 0.80 | Smode3 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 1.25 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.80 | 1 | 0.80 | Smode3 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 1.50 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.25 | Smode3 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 1.75 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 2.00 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 2.25 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 2.50 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 2.75 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 3.00 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 3.25 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 3.50 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 3.75 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 4.00 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 4.25 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 4.50 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 4.75 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 5.00 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 5.25 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | Smode2 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 5.50 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | Smode1 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 5.75 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | Smode1 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 6.00 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | Smode1 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 6.25 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | Smode1 | 0.00 |

| VRU’s Speed/(m/s) | VRU | fvisibility | Without Control | Driver Control | Driver-2D AEBS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x/m | y/m | fbrake | vcollision/(m/s) | fbrake | vcollision/(m/s) | fbrake | vcollision/(m/s) | ||

| 1.00 | 3.00 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 0.50 | 0 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 1.00 | 1 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 1.25 | 1 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 1.50 | 1 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 2.00 | 3.00 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 0.50 | 0 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 1.00 | 1 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.80 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 1.25 | 1 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.80 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 1.50 | 1 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 3.00 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 |

| 3.00 | 0.50 | 0 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 1.00 | 1 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 1.12 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 1.25 | 1 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.80 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 1.50 | 1 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 4.00 | 3.00 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.95 |

| 3.00 | 0.50 | 0 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.95 | |

| 3.00 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.95 | |

| 3.00 | 1.00 | 1 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 1.12 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 1.25 | 1 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.80 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| 3.00 | 1.50 | 1 | 0 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Xie, B.; Song, M. Optimization of AEBS for Heavy Goods Vehicles Incorporating Driver’s Control and 3D Visibility of Vulnerable Road Users. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010516

Zhang X, Xie B, Song M. Optimization of AEBS for Heavy Goods Vehicles Incorporating Driver’s Control and 3D Visibility of Vulnerable Road Users. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):516. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010516

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xi, Binglei Xie, and Mingtao Song. 2026. "Optimization of AEBS for Heavy Goods Vehicles Incorporating Driver’s Control and 3D Visibility of Vulnerable Road Users" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010516

APA StyleZhang, X., Xie, B., & Song, M. (2026). Optimization of AEBS for Heavy Goods Vehicles Incorporating Driver’s Control and 3D Visibility of Vulnerable Road Users. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010516