Manna SafeioD: A Framework and Roadmap for Secure Design in the Internet of Drones

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement and Motivation

1.2. Goals and Contributions

- A threat assessment methodology that accounts for operational context variability and environmental factors specific to IoD deployments.

- A novel and clear definition of procedures for device risk analysis.

- Security control establishment and certificate validation processes.

- A CLI-based tool that provides a simple interface for interacting with the framework.

- Mathematical Formalism and Threat Modeling: We introduce a formal mathematical representation of IoD attacks, clearly defining the entities involved, attack behaviors, and related security aspects. This approach establishes a general model applicable to various attack scenarios, supporting rigorous analysis concerning model correctness, computational complexity, and systematic vulnerability assessments.

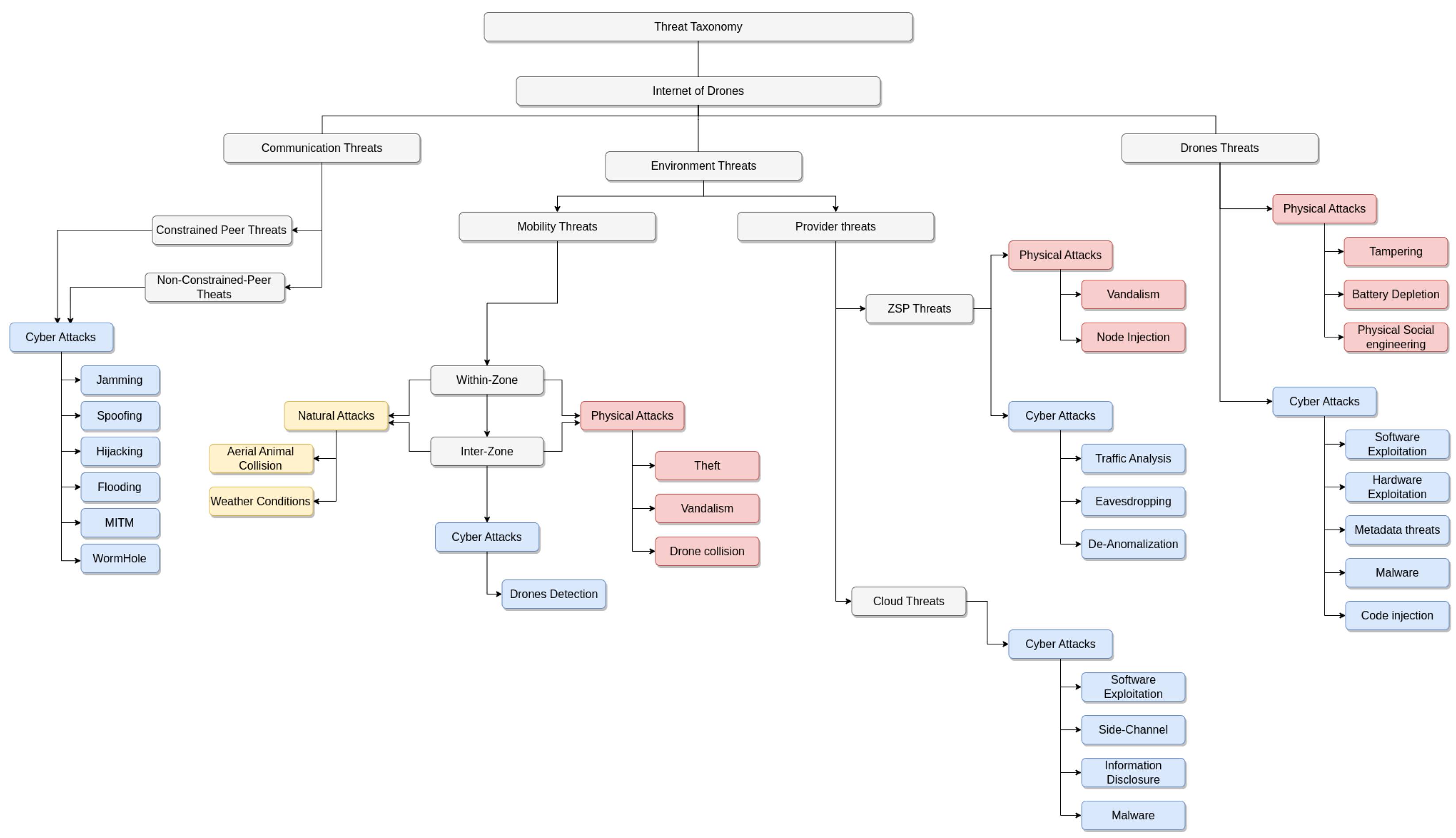

- Integrated Taxonomy of Attacks: We propose a unified attack taxonomy based on three critical dimensions: the primary threat source, the attack behavior, and associated privacy and security issues. This taxonomy comprehensively categorizes threats into Communication Threats, Environment Threats, and Drone Threats, providing a foundational framework for future research and threat mitigation strategies.

- RQ1 (Security Requirements Elicitation): Can the Manna SafeIoD framework effectively generate context-appropriate security requirements for heterogeneous IoD components, and to what extent can it recommend suitable lightweight implementations?

- RQ2 (Risk Assessment Validity): Does the risk propagation model accurately predict attack propagation patterns in IoD network topologies, and do the computed risk scores correlate with observed security outcomes?

- RQ3 (Cross-Context Applicability): Can the framework adapt its certification workflow to diverse operational contexts—spanning resource-constrained civilian devices to mission-critical military deployments—while maintaining acceptable usability for practitioners with varying security expertise?

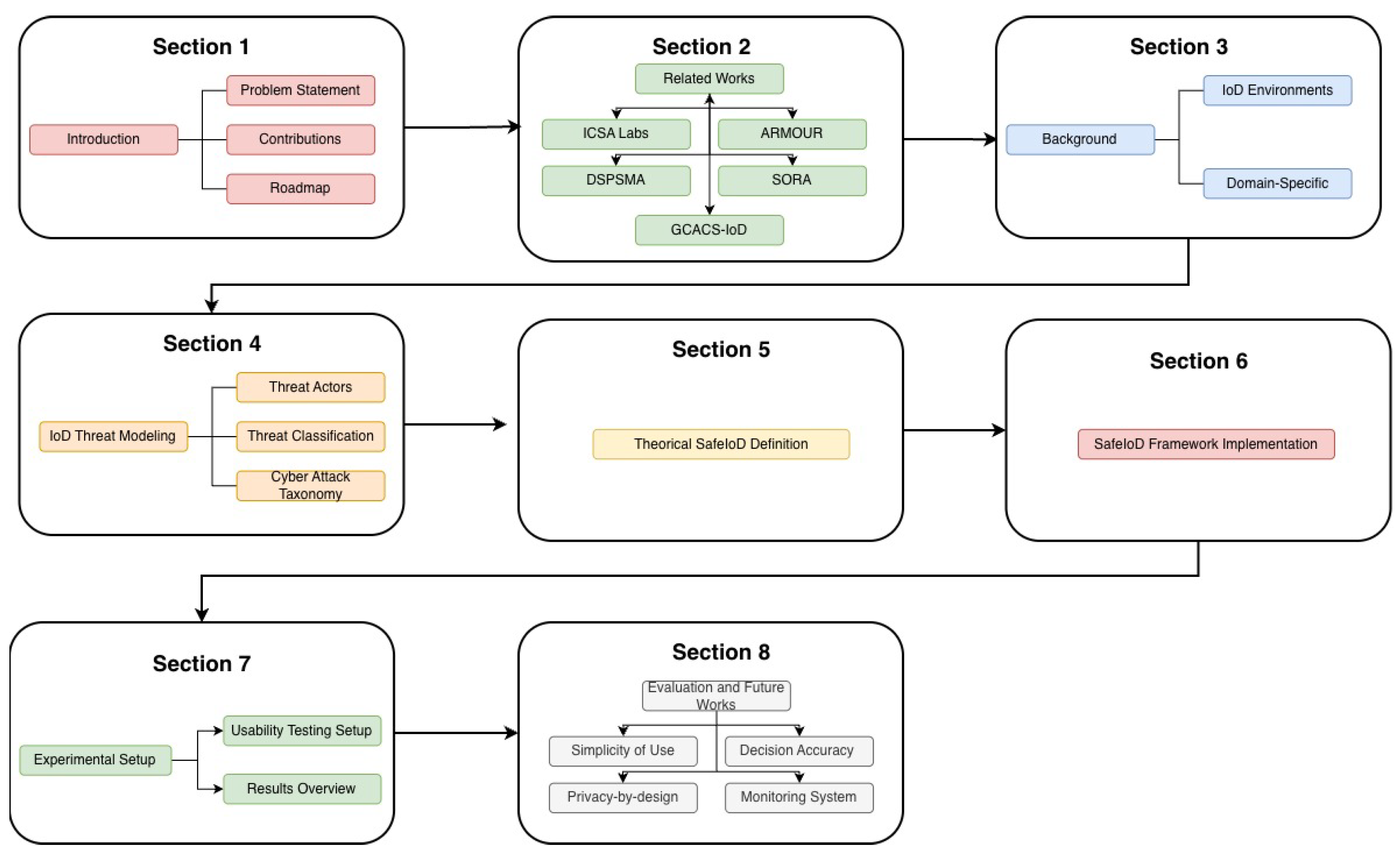

1.3. Paper Organization

2. Related Works

2.1. Common Criteria

2.2. ICSA Labs

2.3. ARMOUR

2.4. DSPSMA

2.5. SORA

2.6. GCACS-IoD

2.7. Other Certification Processes

3. Background

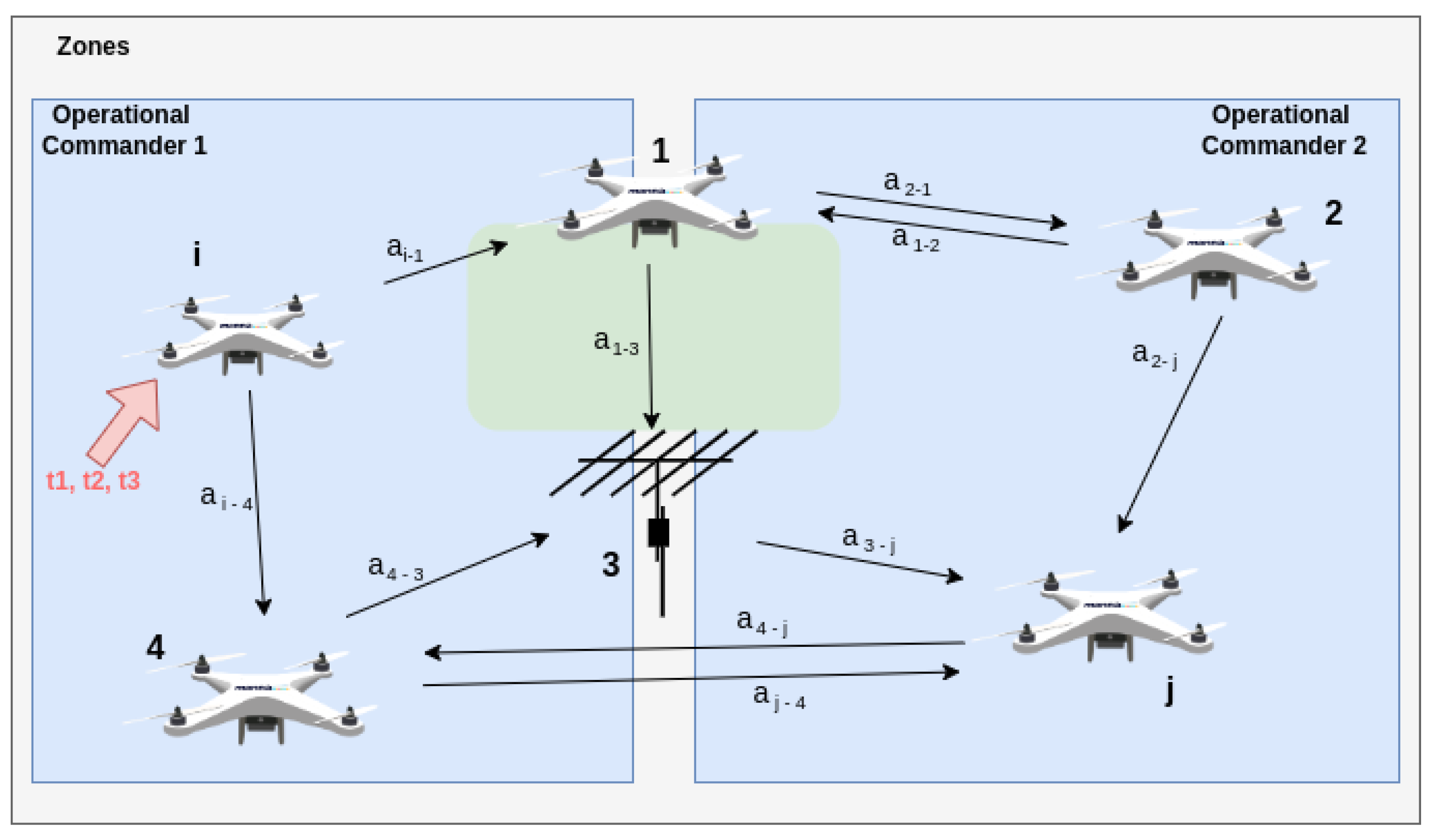

3.1. IoD Environments

- UAV Node (Drone): Defined as an aerial unit compliant with specific hardware and software protocols required to join the network. Beyond simple flight capabilities, this node must possess the computational resources to execute network tasks securely;

- Zone Service Provider (ZSP): While Gharibi et al. [1] originally coined this term for grounded airspace management, we expand its scope. In our framework, a ZSP represents any infrastructure entity—such as a Ground Control Station (GCS)—responsible for orchestrating navigation, enforcing policies, and guaranteeing Quality of Service (QoS) for connected nodes;

- Drone-as-a-Service (DaaS): This concept encapsulates the functional role of the UAV within the IoD. It signifies a paradigm where the drone acts as a service provider node, collaborating with other entities to fulfill specific user demands;

- Service Consumer (IoD User): The entity requesting services from the aerial network. Consumers range from human operators and government bodies to automated endpoints in external networks (e.g., a node in a VANET). Understanding the consumer’s profile is crucial for tailoring privacy levels;

- Operational Context (IoD Scenario): Refers to the physical and logical environment of deployment, such as dense urban centers or remote agricultural fields. Each context imposes unique constraints and security requirements that the IoD architecture must address.

3.2. Domain-Specific Implementations and Market Trends

- Disaster Management and Response: UAVs are critical assets for public safety during crises like tsunamis, floods, or hostile attacks [55]. In these scenarios, the primary function is the real-time transmission of high-bandwidth data (video feeds) to command centers to aid decision-making;

- Environmental Sensing: Functioning as airborne IoT nodes, drones extend the range of data acquisition networks. They are pivotal for tasks such as atmospheric pollution analysis and wildfire detection [56]. These units typically carry specialized payloads, including LIDAR, scatterometers, and spectrometers, to aggregate data from ground sensors or perform direct measurements;

- Infrastructure Integrity Assessment: In sectors like civil engineering and industrial manufacturing, UAVs provide a safer alternative for inspecting physical assets. By utilizing directed video streams and sensor telemetry, they allow experts to monitor hazardous industrial zones or construction progress remotely [57];

- Intelligent Transportation Support: Drones serve as a complementary layer to terrestrial traffic management [58,59]. They assist in identifying congestion, accidents, and road hazards. Furthermore, through integration with Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks (VANETs), aerial nodes can broadcast alerts to drivers. This application requires the handling of sensitive information, including license plates and driver behavior patterns;

- Public Security and Crowd Control: For civil surveillance, aerial units offer a vantage point for monitoring large gatherings or riots [60]. The architecture typically involves continuous video uplink to a central monitoring station to assess crowd dynamics;

- Smart Farming: Precision agriculture utilizes UAVs to optimize inputs and maximize yields, proving to be a time-efficient solution for modern farming [55]. Similarly to infrastructure monitoring, this domain relies heavily on visual and spectral sensors to assess crop health and soil conditions;

- Last-Mile Logistics: Although still facing regulatory hurdles, aerial delivery (e.g., Amazon Prime Air) represents a growing sector for transporting goods and medical supplies [61]. Security is paramount here, as the network must process precise geolocation data and customer details while ensuring safe path planning;

- Aerial Network Extension: A novel application involves using drones as flying base stations to enhance wireless coverage or throughput for ground users. In this configuration, the UAV becomes a critical infrastructure node, relaying massive amounts of user-generated traffic [62];

- Renewable Energy Infrastructure: IoD systems have become instrumental in the global energy transition, enabling efficient inspection and maintenance of solar farms, wind turbines, and power grid infrastructure [63]. Equipped with thermal imaging and LiDAR sensors, drones can detect panel defects, blade cracks, and transmission line anomalies in real-time, reducing inspection time by up to 70% compared to manual methods while eliminating worker exposure to hazardous conditions [64]. The market for drones in power generation and distribution is projected to reach USD 4.4 billion by 2030, reflecting the sector’s critical dependence on IoD for predictive maintenance and operational resilience [65].

4. IoD Threat Modeling

4.1. Threat Actors

- Privileged Insider: Government officials, institutional personnel, maintenance technicians with direct physical access to drones/ZSPs. Can bypass technical controls through physical access and insider knowledge.

- Proximate External: Malicious hackers, unauthorized surveillance entities operating within service zone range. Enable RF attacks, signal interception, and electronic warfare techniques.

- Unintentional: Wildlife collisions, adverse weather, electromagnetic interference from legitimate sources. Non-malicious but can significantly impact operations and mask malicious activities.

4.2. Threat Classification

- Natural Threats: Within the realm of IoD security, environmental vulnerabilities present pressing concerns that extend beyond traditional cybersecurity paradigms. Drones traversing airspace encounter various natural elements that can affect their operations, creating exploitable conditions for malicious actors. Environmental threats include meteorological phenomena such as wind shear, microbursts, electromagnetic storms, and atmospheric conditions that can disrupt navigation and communication systems. Neglecting these environmental factors provides attackers with opportunities to exploit adverse conditions, using weather patterns or aerial wildlife as cover for malicious activities, thereby disrupting IoD operations and compromising security postures [9].

- Physical Threats: Drones are inherently susceptible to physical attacks stemming from human intervention and environmental obstacles. These attacks encompass vandalism through deliberate damage or destruction of drone platforms [53], theft involving unauthorized appropriation of drone assets [69], and various forms of eavesdropping including ground-based signal interception and payload monitoring [70]. Physical threats pose substantial privacy and operational risks within the IoD ecosystem, causing direct harm to devices while exhibiting destructive behavior that can compromise mission integrity and data confidentiality.

- Cyber Threats: These threats exploit various network elements including drones, communication links (drone-to-drone and drone-to-infrastructure), cloud data storage systems, and ground control infrastructure. Cyber attacks often occur stealthily without causing immediate physical damage, making detection and attribution challenging. These threats are categorized into passive attacks such as automatic drone detection systems [71] and traffic analysis attacks [72], and active attacks including jamming techniques [73], various spoofing methods [74], hijacking attempts [23], and both software [75] and hardware exploitation techniques [76].

4.3. Cyber Attack Taxonomy

- Jamming Attacks: These constitute denial-of-service attacks targeting communication channels between drones and ground control systems or other network components. Jamming attacks disrupt radio frequency communications, making coordination between drones and ground control stations difficult or impossible. In such scenarios, affected drones lose situational awareness, navigation capabilities, and command reception, potentially resulting in mission failure or catastrophic incidents [21]. Advanced jamming techniques may employ frequency-hopping or adaptive algorithms to overcome anti-jamming countermeasures.

- Spoofing Attacks: These exploit vulnerabilities in data links between drones and ground control systems, enabling interception and manipulation of unencrypted or poorly protected signals to mislead drone navigation systems. Spoofing attacks can target various systems including GPS receivers, altimeters, and communication protocols, potentially resulting in loss of accurate positional information, trajectory deviation, or complete drone theft [5]. Sophisticated spoofing attacks may combine multiple signal sources to create convincing false environments that are difficult to detect.

- Hijacking Attacks: These involve transmission of unauthorized ground control signals designed to usurp legitimate control authority and force drones to respond to attacker commands. Hijacking attacks can result in complete loss of drone control, unauthorized mission redirection, or deliberate destruction through commands such as emergency shutdown during flight [53]. Advanced hijacking techniques may exploit authentication weaknesses or session management vulnerabilities to establish persistent unauthorized control.

- Flooding Attacks: These attacks aim to overwhelm networks and individual services with massive volumes of data packets, preventing drones from accessing critical network services. Flooding attacks are categorized into Denial of Service (DoS) attacks targeting individual components [77] and Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks leveraging multiple attack sources to amplify impact [78]. In IoD contexts, flooding attacks may specifically target bandwidth-constrained communication links or resource-limited drone processing capabilities.

- Wormhole Attacks: These represent sophisticated routing-based attacks where malicious actors strategically position compromised drones or infrastructure components to create unauthorized communication tunnels. In wormhole attacks, two malicious nodes establish covert communication channels that bypass normal network routing protocols. Node A intercepts data packets in geographical area X and transmits them to Node B, which replays them in a different location, creating false proximity relationships and enabling various secondary attacks. Related attack variants include selective forwarding [79] and black-hole attacks [80] that share similar methodological foundations.

- Hardware/Software Exploitation: Both drone platforms and ground control systems are vulnerable to various forms of malicious software including malware [81], trojan horse programs [82], keyloggers, and side-channel attacks [83]. These exploits may be embedded during manufacturing processes or introduced through subsequent software updates or maintenance procedures. In IoD environments, successful exploitation can result in complete loss of operational security, unauthorized access to confidential mission data, or persistent compromise of communication channels that enables long-term surveillance or sabotage activities.

5. Manna SafeIoD Framework Definition

- Standardization: The utilization of drones is not confined to a specific region or country; therefore, certification should be standardized to provide a harmonized process across different contexts, domains, and countries.

- Context: Effective certification requires assessing the operational context of the device, including its intended use, expected data flows, and environmental constraints. This assessment is particularly difficult because the final application scenario is frequently unknown at the time of manufacturing.

- Environment: IoD systems and devices operate in physical environments with variable conditions that can affect their level of security. Therefore, the maturity of a device may vary depending on the deployment aspects to which it may be exposed. At the end of the initial certification process, the device may be evaluated against a set of security requirements, but the initial tested configuration and maturity level may be affected due to software updates, changes in system configuration, or the need to be used in different operational contexts. Considering that software updates and patches are quite frequent due to the discovery of new vulnerabilities, it is necessary to define a lightweight recertification process design to reflect the changes introduced in the devices.

5.1. Context Establishment

- Deployment Environment: Detailed characterization of the physical and geographical environment, including:

- Type of setting: indoor/outdoor, urban/rural, controlled/uncontrolled airspace.

- Physical constraints: signal interference, electromagnetic exposure, terrain.

- Environmental factors: wind, precipitation, temperature extremes.

- Mission Operation Type: Definition of the intended mission profile, including:

- Purpose: surveillance, inspection, delivery, data collection.

- Tasks: payload delivery, sensing operations, communication relays.

- Regulatory Environment: Mapping of applicable legal and regulatory obligations:

- National/international aviation regulations (e.g., FAA, EASA, ANAC).

- Cybersecurity frameworks and data protection laws (e.g., GDPR, LGPD (Brazilian GRDP), ISO/IEC 27001 [87]).

- Domain-specific standards for communication and safety.

- Deployment and Maintenance Processes: Full lifecycle documentation:

- Initial installation, configuration routines, and security onboarding.

- Firmware updates, patch cycles, and preventive maintenance.

- Roles and responsibilities of operational personnel.

- Contingency Procedures: Preparedness for failure and emergencies:

- Protocols for link loss, GNSS spoofing, battery depletion.

- Emergency return, shutdown, or recovery protocols.

- Redundant communication mechanisms and fallback strategies.

5.2. Risk Assessment

- Threat Enumeration: This phase entails the systematic discovery of potential adverse events, mapping their origins and probable repercussions. The enumeration is data-driven, utilizing inputs such as device manufacturing specifications, operational mission profiles, and connectivity interfaces. This step is directly grounded in the IoD threat modeling previously established.

- Risk Quantification: Following identification, this process assigns a magnitude to the risk associated with the Target of Evaluation (ToE). Recognizing that quantification often suffers from subjectivity, our approach mitigates imprecision by employing a specialized expert system to standardize the estimation using industry-standard metrics (CVSS).

- Acceptability Analysis: The final stage involves benchmarking the calculated risk levels against pre-established security thresholds. This determines whether the residual risk falls within the tolerance levels defined by stakeholders or regulatory compliance frameworks.

- Phase 1 (Module Characterization): We treat every IoD entity as an abstract module. We define the multi-set of threat severity levels for a module as (Equation (1)). To establish a baseline, we select the threat with the maximum CVSS score () as the primary risk indicator (Equation (2)).The baseline risk estimation () for a single module is derived using Equation (3), which functions as a ratio of the threat magnitude () against the effectiveness of security controls.We map this numerical value to a qualitative severity scale:

- Phase 2 (Adjacency Analysis): We calculate the transmission potential between direct neighbors. This yields the coefficient , representing the probability of risk propagating from module x to y. This is computed by weighting the estimated risk of the neighbor () against the specific threat relationship of the link.

- Phase 3 (Path Aggregation): We determine the Total Transmission Coefficient. This involves identifying all valid propagation paths from a source i to any target j. The coefficient is the aggregate of sequential transmission probabilities () along these routes.

- Phase 4 (Event Probability): A threat detected on module i represents a probability, not a certainty. We calculate both the likelihood and the potential impact of the security event.

- Phase 5 (Systemic Integration): Finally, the global risk contributed by a source i is computed by integrating the local estimation, network transmission coefficients, and event probability.

Formalization of Systemic Propagation

- Inherent Threat Severity (): Derived from the CVSS Base Score of the vulnerability.

- Security Gap (): Represents the residual vulnerability after applying controls, calculated as .

- Balanced Profile (): Assigns equal importance to the existence of a known threat and the lack of mitigation. This is the default setting for general IoD certification.

- Threat-Centric Profile (): Used in high-threat environments (e.g., military zones) where the mere presence of a high-severity vulnerability (high CVSS) drives the risk score, regardless of partial mitigations.

- Control-Centric Profile (): Used in controlled environments where the focus is strictly on compliance gaps; risk is primarily driven by the absence of mandatory controls.

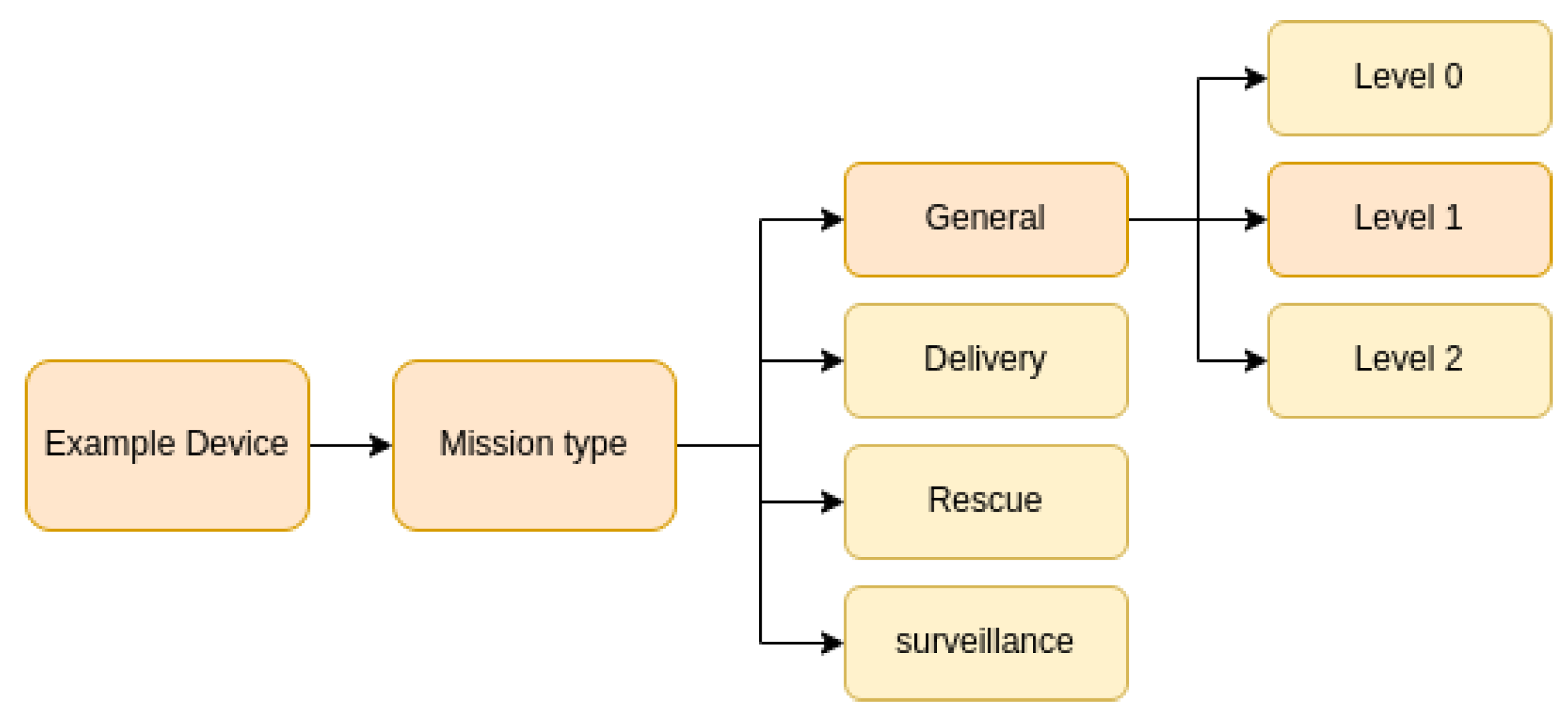

5.3. Maturity Report

- Level 0 (Do not fly) —Denotes the complete absence of security safeguards. Devices in this category face extreme exposure to threats and fail to comply with the essential security standards necessary for safe deployment.

- Level 1 (Operational necessity only) —Denotes that the device incorporates basic security protocols and meets minimum operational requirements, rendering it eligible for certification. However, additional security measures identified during modeling threat must be implemented within the stipulated timeframe to maintain certification.

- Level 2 (Safe to fly) —Indicates advanced security protocols and full compliance with basic and critical mission requirements. The evaluation process reveals no critical threats to the target system.

- Target of Evaluation (TOE): Within the framework of CC, a TOE encompasses a collection of software, firmware, and/or hardware, potentially accompanied by associated guidance. In our context, the TOE also encompasses the protocol under examination and the testing environment.

- Protection Profiles (Levels of Security): In this case designated as levels 0, 1, and 2, these profiles delineate the level of security corresponding to the risk posed by the scenario being evaluated.

- Certification entity: Consists of the device’s certification authority.

5.4. Security Requirements

- Qualify Mission Type This initial phase consolidates information derived from the Context Establishment and Risk Assessment phases. This classification informs subsequent security decisions by aligning them with the level of exposure, autonomy, and communication dependencies inherent to the mission.

- Identify Threats In this activity, we systematically identify threats applicable to the IoD system. Threats are categorized into three primary domains: Communication Threats, Environment Threats, Drone-Specific Threats. Each identified threat contributes to shaping the security posture required. Threat categorization should be performed based on the context presented in Section 4

- Identify Endpoint Hardware IoD systems depend on various physical endpoints, including base stations, routers, embedded controllers, and smart gateways. This phase focuses on cataloging and validating the hardware components within the IoD infrastructure, emphasizing the use of authenticated and certified components to reduce supply chain attacks and physical compromise.

- Identify Sensor Data Given that drones interact with the physical world primarily through sensors and actuators, this activity identifies the characteristics of all sensing components (e.g., cameras, altimeters, LIDARs, GPS receivers).

- Elicit Security Requirements The final activity synthesizes all prior analyses to elicit formalized security requirements.

- Authentication: In the domain of the IoD, the security requirements for authentication and integrity are paramount, given the context of communication between different devices at different layers and protocols. Specifically in the context of UAVs, due to resource constraints as described by [79], authentication schemes must be extremely lightweight to minimize computational overhead and data transfer requirements, ensuring efficient and secure communication between drones, ZSPs and other systems [92]. The verification of data integrity and authenticity is equally critical, ensuring that critical information, such as configuration files or flight plans, has not been tampered with by unauthorized parties [121].

- Access Control: IoD ecosystems are predominantly characterized by latency-sensitive operations, where stakeholders demand instantaneous telemetry from aerial nodes. However, providing unmediated, real-time access to UAVs creates a significant attack surface. Without rigorous data governance, a single compromised node could serve as a pivot point, jeopardizing the integrity of the entire network topology. Consequently, implementing granular access control protocols is mandatory. This is particularly critical in multi-layered architectures where distinct interaction privileges are required—for instance, differentiating between end-to-end transport permissions and service-layer application access [44].

- Network Security: The IoD ecosystem, being large and densely connected, requires proper network connection mechanisms to maximize the positive impact of the technology. If the network fails, all other security measures are compromised, affecting the entire IoD ecosystem. As highlighted [122], unsecured internet connections, particularly over WiFi and wireless networks, are frequently used for communication within the UAV network. Several works highlight the use of 5G [105] and 6G [107] mobile networks for the efficient implementation of IoD networks. In this context, it is necessary to think about encompassing the drone’s behavior in adverse situations, the confidentiality of communication between network nodes, and privacy. For instance, in a critical application, drones equipped with sensors collect data, which is then transmitted to a central server for analysis. Ensuring the security of this wireless communication is crucial to prevent unauthorized access to sensitive data, thereby safeguarding intellectual property and operational secrets.

- Data security: While legacy industrial control systems typically prioritize availability and integrity to mitigate economic loss, the Smart City paradigm necessitates a rebalancing of security objectives. The IoD introduces a complex triad of conflicting requirements. First, the heterogeneity of the fleet imposes strict resource constraints, demanding lightweight security mechanisms. Second, the mission-critical nature of UAV operations mandates rigorous protection standards despite these hardware limitations. Finally, the massive volume of high-frequency telemetry raises significant privacy concerns. As highlighted by Solangi et al. [123], uncontrolled data streams allow for the reconstruction of granular user profiles. Consequently, implementing robust data anonymization and obfuscation strategies is essential to reconcile operational efficiency with privacy preservation.

- Resilience: In the context of IoD, resilience is defined as the system’s capacity to sustain operational continuity even when partially subverted. Security mechanisms must facilitate the survival of critical functions despite the compromise of individual nodes. For example, if a UAV’s primary communication link is neutralized, the architecture should autonomously reroute tasks or activate auxiliary channels to prevent service disruption. Following the taxonomy proposed by Laszka et al. [124], we achieve this via three pillars: redundancy (provisioning spare components to absorb faults), diversity (utilizing heterogeneous technologies to limit common-mode vulnerabilities), and hardening (reinforcing individual elements against direct exploitation).

- Monitoring: Continuous behavioral analysis is the cornerstone of detecting malicious activities, typically implemented through Intrusion Detection Systems (IDSs). Within the IoD domain, this requirement bifurcates into two essential capabilities: pervasive infrastructure visibility and the agility to mitigate both known signatures and emergent zero-day threats. This surveillance is particularly critical given the heterogeneous nature of drone networks, which often integrate legacy hardware. Since these older components may lack support for modern security patches, real-time monitoring serves as the primary compensatory control against the exploitation of unpatched vulnerabilities.

- Physical Security: Establishing a root of trust often relies on hardware, as physically subverting silicon is significantly more resource-intensive and costly than software exploitation. Consequently, a secure hardware foundation is essential for embedded device integrity. Conversely, the physical layer presents unique risks; the existence of manufacturing backdoors or unsecured legacy debug interfaces (e.g., JTAG) can bypass software defenses, effectively compromising the entire device stack from the bottom up.

- Regulation and standard: To safeguard citizen privacy and national security, adherence to jurisdictional legal frameworks is mandatory. In our analysis, the device must demonstrate compliance with a constellation of statutes, including the Cybersecurity recommendations for 5G Networks, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) for data sovereignty, and the aviation-specific mandates of the NIS Directive. Furthermore, alignment with the Electronic Communications Code and relevant Cyber Security Laws—which govern the certification of devices and applications—is essential, as these regulations directly influence the architectural validity of the Drone Internet.

5.5. Certification Monitoring and Review

- Manufacturing Phase: The genesis of the device’s lifecycle lies in the manufacturing stage. This critical phase involves hardware assembly, firmware provisioning, and the initial configuration required for deployment in IoD environments. It is at this juncture that our framework is applied to execute the certification process, ensuring the device undergoes a rigorous conformity assessment based on Secure-by-Design principles. As articulated by Sequeiros et al. [125], this paradigm dictates that security attributes must be ingrained and optimized throughout the SDLC. Consequently, protection mechanisms are not merely added at the end but are actively monitored from initial requirements engineering and architectural design through to implementation and final validation. Figure 7 depicts the strategic integration of the framework within this design workflow.After the manufacturing the bootstrapping phase usually includes a set of processes by which an IoD device joins a network in a specific domain; e.g., surveillance [126], rescue [127], delivery [128]. During this phase, the device is configured for a specific context and the context information should be embedded label (which should be up-to-date).

- Operation: During the operation phase, the device delivers its intended functionality in the target environment. In this stage, continuous monitoring is essential to detect threats that may not have been identified during the initial certification—particularly emerging threats such as zero-day vulnerabilities. The Manna SafeIoD framework does not prescribe a specific mechanism for active vulnerability detection; rather, it is the responsibility of the certifying authority to define and implement appropriate monitoring procedures. These procedures must be explicitly stated on the certification label and transparently communicated to the IoD device’s manufacturer or supplier. Upon detection of a new threat, the manufacturer may determine that a software or hardware update is required. If such updates introduce substantial changes—particularly those affecting the device’s security posture—the device may be required to undergo a new certification cycle, and its existing security level or label may be suspended or revoked. To ensure compliance with operational security requirements, the device shall be subject to active runtime monitoring via the Manna SafeIoD governance architecture, detailed in the following section.

- Decommissioning: When the IoD device is no longer needed by the consumer or reaches the end of its life cycle and is no longer supported by the provider, a series of decommissioning processes must be executed. These include revoking certification for the device model, securely erasing all consumer and product-related files, both from the device and the certifying servers, revoking any cryptographic materials, and disassociating the device from consumer accounts, if the consumer still maintains an account with the provider.

6. Manna SafeIoD Framework Implementation

6.1. Establishing Context (User Interface)

- Device Classification: Type and category of IoD component under evaluation (drone, ZSP, gateway, ground control station).

- Mission Profile: Target operation type and criticality level.

- Data Handling Characteristics: Information storage requirements, data sensitivity classification (normal, sensitive, critical), and cloud integration dependencies.

- Network Topology: Type and frequency of interactions with Zone Service Providers (ZSPs) and other network entities.

- Regulatory Context: Applicable regulatory frameworks and compliance requirements (e.g., ANAC, FAA, EASA, GDPR, LGPD).

- Threat Exposure: Physical and cyber threat landscape, including potential adversarial access scenarios.

| Algorithm 1 Network Topology JSON Schema |

| { |

"topology_id": "string (UUID)", "nodes": [ { "node_id": "string (UUID)", "device_spec": "<Device Specification Object>", " mission_profile": "<Mission Profile Object>" } ], " edges": [ { "source": "string (node_id)", "target": "string (node_id)", "protocol": "enum (WiFi|LTE|5G|LoRa|Wired)", "encrypted": "boolean", "bidirectional": "boolean", "trust_level": "float [0.0-1.0]" } ] |

| } |

6.2. Risk Calculator

| Algorithm 2 IoD Risk Assessment and Propagation |

| Require: Context parameters C, IoD topology graph , threat database Ensure: Overall system risk , module risk vector , security requirements |

|

6.3. Security Requirements Generator

- User Response Analyzer: This component performs multi-level analysis on user responses, distinguishing between binary indicators (yes/no answers), categorical classifications (e.g., mission type: surveillance, delivery, inspection), and sensitivity gradations (e.g., data classification: normal, sensitive, critical). The analyzer implements a rule-based inference engine that correlates user inputs with the five security requirement elicitation activities presented in Figure 6. The extracted parameters are normalized and encapsulated in a structured requirements context object , which serves as input to the Security Requirements Selector component.

- Security Requirements Selector implements a constraint-based mapping algorithm that systematically selects appropriate security requirements from a curated repository aligned with the eight mandatory categories: Authentication, Access Control, Network Security, Data Security, Resilience, Monitoring, Physical Security, and Regulation (as defined in Table 6).Algorithm 3 formalizes the selection procedure. The algorithm iterates through the eight security categories, applying context-aware filters and risk-based prioritization to construct a tailored requirement set for each module i in the IoD ecosystem.The requirement database maintains a structured repository of security requirements sourced from established standards (ISO/IEC 27001, NIST Cybersecurity Framework), domain-specific best practices [106], and peer-reviewed IoD security research (as cataloged in Table 6). Each requirement entry includes metadata specifying applicable IoD component types (drone, ZSP, gateway, cloud service), implementation complexity ratings, and interdependencies with other requirements.

- Requirements Aggregator: consolidates individual module requirements into a comprehensive, system-level security specification. When multiple modules generate overlapping requirements (e.g., mutual authentication between drone and ZSP appears in requirements for both components), the aggregator merges them into unified, bidirectional requirements while preserving module-specific implementation details. he aggregator identifies cross-module dependencies using a directed acyclic graph (DAG) representation [133]. For instance, if Module A requires encrypted communication channels and Module B mandates key management infrastructure, the aggregator ensures both requirements are present and properly sequenced in the implementation roadmap. The aggregator also persists the complete requirement provenance chain—linking each requirement to its originating threat, risk score, context parameter, and applicable security standard—enabling full traceability throughout the certification lifecycle.

| Algorithm 3 Security Requirements Selection |

| Require: Requirements context , module risk vector , threat set , requirement database Ensure: Module-specific security requirements |

|

6.4. Output Interface

6.5. System Components

6.6. Modular Architecture and Scalability

6.6.1. Architectural Modularity Benefits

6.6.2. Practical Configuration Examples

6.6.3. Module Interdependency Management

7. Experimental Setup

7.1. Usability Testing Setup

7.1.1. Software Implementation Test Scenario for Drone Firmware

7.1.2. Software Implementation Test Scenario for Cloud Application Based for ZSP Integration

7.1.3. Hardware Implementation Test Scenario for UAV Security Modules

7.1.4. Hardware Implementation Test Scenario for Reconfigurable UAV Hardware

7.1.5. Certification Process Test Scenario with Military Application

7.2. Results Overview

- V1—Forced Telnet Authentication Bypass (CVSS 8.0): Partially mitigated through vendor-provided security patches;

- V2—Unprotected Telnet Service (CVSS 7.5): Mitigated via MAC filtering and SSID obfuscation;

- V3—Deauthentication Attack Susceptibility (CVSS 9.0): Unmitigated due to C2 software lacking encryption capabilities.

7.3. Research Limitations

7.3.1. Simulation and Experimental Validation Constraints

7.3.2. Participant Study

7.3.3. Framework Scope Boundaries

8. Evaluation and Future Works

8.1. Simplicity of Use

8.2. Decision Accuracy and Requirement Selection Validation

8.3. Algorithm Database Limitations and Design Rationale

8.4. Secure-by-Design Process

8.5. Privacy-by-Design Issues

8.6. Monitoring System

- represents the certification state matrix;

- denotes the trust state matrix;

- captures the behavioral observation matrix;

- defines the active policy configuration.

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gharibi, M.; Boutaba, R.; Waslander, S.L. Internet of drones. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 1148–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozmen, M.O.; Behnia, R.; Yavuz, A.A. IoD-crypt: A lightweight cryptographic framework for Internet of drones. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.06829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batth, R.S.; Nayyar, A.; Nagpal, A. Internet of robotic things: Driving intelligent robotics of future-concept, architecture, applications and technologies. In Proceedings of the 2018 4th International Conference on Computing Sciences (ICCS), Jalandhar, India, 30–31 August 2018; pp. 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, G.; Sharma, V.; Gupta, T.; Kim, J.; You, I. Internet of Drones (IoD): Threats, Vulnerability, and Security Perspectives. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.00203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; He, D.; Kumar, N.; Choo, K.K.R.; Vinel, A.; Huang, X. Security and Privacy for the Internet of Drones: Challenges and Solutions. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bor-Yaliniz, I.; Salem, M.; Senerath, G.; Yanikomeroglu, H. Is 5G ready for drones: A look into contemporary and prospective wireless networks from a standardization perspective. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2019, 26, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhunia, S.; Sengupta, S. Distributed adaptive beam nulling to mitigate jamming in 3D UAV mesh networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 26–29 January 2017; pp. 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Tao, X.; Darwazeh, I. Power allocation for proactive eavesdropping with spoofing relay in UAV systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 26th International Conference on Telecommunications (ICT), Hanoi, Vietnam, 8–10 April 2019; pp. 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Yahuza, M.; Idris, M.Y.I.; Ahmedy, I.B.; Wahab, A.W.A.; Nandy, T.; Noor, N.M.; Bala, A. Internet of Drones Security and Privacy Issues: Taxonomy and Open Challenges. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 57243–57270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Force, J.T. Risk management framework for information systems and organizations. NIST Spec. Publ. 2018, 800, 37. [Google Scholar]

- NIST SP 800-37 Rev. 2; Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy. National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2018.

- Ernst, D.; Martin, S. The Common Criteria for Information Technology Security Evaluation-Implications for China’s Policy on Information Security Standards. East-West Cent. Work. Pap. 2010, 108, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 20924:2024; Internet of Things (IoT) and Digital Twin—Vocabulary. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Mohamed, A.M.A.; Hamad, Y.A.M. IoT security: Review and future directions for protection models. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computing and Information Technology (ICCIT-1441), Tabuk, Saudi Arabia, 9–10 September 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, M.; Fagan, M.; Megas, K.N.; Scarfone, K.; Smith, M. IoT Device Cybersecurity Capability Core Baseline; US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020.

- Cybersecurity, C.I. Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity. 2018; p. 4162018. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/cswp/nist.cswp.04162018.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Kohler, C. The EU Cybersecurity Act and European standards: An introduction to the role of European standardization. Int. Cybersecur. Law Rev. 2020, 1, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, N.D.; Hdd, I.; EAL, C.C. Certification Report. Int. Cybersecur. Law Rev. 2010, 1, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, P.Y. A survey of cyberattack countermeasures for unmanned aerial vehicles. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 148244–148263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, J.; Ma, D.; Li, J.; Wei, J. Survey on unmanned aerial vehicle networks: A cyber physical system perspective. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2019, 22, 1027–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, R.; Oligeri, G.; Tedeschi, P. JAM-ME: Exploiting jamming to accomplish drone mission. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security (CNS), Washington, DC, USA, 10–12 June 2019; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sathyamoorthy, D.; Fitry, Z.; Selamat, E.; Hassan, S.; Firdaus, A.; Zaimy, Z. Evaluation of the vulnerabilities of unmanned aerial vehicles (uavs) to global positioning system (GPS) jamming and spoofing. Def. S T Tech. Bull. 2020, 13, 333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Joe, I. Security vulnerability analysis of Wi-Fi connection hijacking on the Linux-based robot operating system for drone systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Computing: Applications and Technologies, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 20–22 August 2018; pp. 473–482. [Google Scholar]

- Almulhem, A. Threat modeling of a multi-UAV system. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 142, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerappan, C.S.; Keong, P.L.K.; Balachandran, V.; Fadilah, M.S.B.M. Drat: A penetration testing framework for drones. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 16th Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA), Chengdu, China, 1–4 August 2021; pp. 498–503. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, K.P. The uav ground control station: Types, components, safety, redundancy, and future applications. Int. J. Unmanned Syst. Eng. 2016, 4, 37. [Google Scholar]

- McEnroe, P.; Wang, S.; Liyanage, M. A survey on the convergence of edge computing and AI for UAVs: Opportunities and challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 15435–15459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamh, F.E.; Karabiyik, U.; Rogers, M. A constructive direst security threat modeling for drone as a service. J. Digit. Forensics Secur. Law 2021, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; McLaughlin, K.; Laverty, D.; Sezer, S. STRIDE-based threat modeling for cyber-physical systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe), Torino, Italy, 26–29 September 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Górniak, S.; Atoui, R.; Fernandez, J.; Quemard, J.-P.; Schaffer, M. Standardisation in Support of the Cybersecurity Certification; Technical Report; European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA): Heraklion, Greece, 2020; Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/recommendations-for-european-standardisation-in-relation-to-csa-i (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Nassar, V. Common criteria for usability review. Work 2012, 41, 1053–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICSA. Internet of Things (IoT) Security Testing Framework; ICSA: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Matheu, S.N.; Hernandez-Ramos, J.L.; Skarmeta, A.F. Toward a cybersecurity certification framework for the Internet of Things. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2019, 17, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.Q.; AS, B.B.; Menon, M.; Ziegler, S.; AS, A.M.P.H.; DG, E.K.; Bianchi, S. Dynamic Security and Privacy Seal Model Analysis. Cited on 2020, 21, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC 15408; Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Evaluation Criteria for IT security—Part 1: Introduction and General Model. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Kang, S.; Kim, S. How to obtain common criteria certification of smart TV for home IoT security and reliability. Symmetry 2017, 9, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluvuri, S.P.; Bezzi, M.; Roudier, Y. A quantitative analysis of common criteria certification practice. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Trust, Privacy and Security in Digital Business, Munich, Germany, 2–3 September 2014; pp. 132–143. [Google Scholar]

- Keblawi, F.; Sullivan, D. Applying the common criteria in systems engineering. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2006, 4, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davri, E.C.; Darra, E.; Monogioudis, I.; Grigoriadis, A.; Iliou, C.; Mengidis, N.; Tsikrika, T.; Vrochidis, S.; Peratikou, A.; Gibson, H.; et al. Cyber Security Certification Programmes. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR), Virtual, 26–28 July 2021; pp. 428–435. [Google Scholar]

- Flatt, H.; Schriegel, S.; Jasperneite, J.; Trsek, H.; Adamczyk, H. Analysis of the Cyber-Security of industry 4.0 technologies based on RAMI 4.0 and identification of requirements. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 21st International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Berlin, Germany, 6–9 September 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Denney, E.; Pai, G.; Johnson, M. Towards a rigorous basis for specific operations risk assessment of UAS. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/AIAA 37th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), London, UK, 23–27 September 2018; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Asghari, O.; Ivaki, N.; Madeira, H. UAV operations safety assessment: A systematic literature review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, S.A.; Yahya, K.; Karuppiah, M.; Kharel, R.; Bashir, A.K.; Zikria, Y.B. GCACS-IoD: A certificate based generic access control scheme for Internet of Drones. Comput. Netw. 2021, 191, 107999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Bera, B.; Wazid, M.; Jamal, S.S.; Park, Y. iGCACS-IoD: An Improved Certificate-Enabled Generic Access Control Scheme for Internet of Drones Deployment. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 87024–87048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation, C. 679 of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC. In Proceedings of the 6th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Art Sgem, Albena, Bulgaria, 22–31 August 2016. OJ L119/1. [Google Scholar]

- Matheu, S.N.; Hernandez-Ramos, J.L.; Skarmeta, A.F.; Baldini, G. A survey of cybersecurity certification for the internet of things. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2020, 53, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellular Telecommunications Industry Association. CTIA Cybersecurity Certification Test Plan for IoT Devices; Cellular Telecommunications Industry Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Al Farsi, A.; Khan, A.; Mughal, M.R.; Bait-Suwailam, M.M. Privacy and security challenges in federated learning for uav systems: A systematic review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 86599–86615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasrouny, H.; Samhat, A.E.; Bassil, C.; Laouiti, A. VANet Security Challenges and Solutions: A Survey. Veh. Commun. 2017, 7, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, K.Y.; Girdler, T.; Vassilakis, V.G. A survey of cyber security threats and solutions for UAV communications and flying ad-hoc networks. Ad Hoc Netw. 2022, 133, 102894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccadoro, P.; Striccoli, D.; Grieco, L.A. An extensive survey on the Internet of Drones. Ad Hoc Netw. 2021, 122, 102600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, D.A.d.J.; Sarker, S.; Bilal, M.; Chamola, V.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. Opportunities and challenges of drones and internet of drones in healthcare supply chains under disruption. Prod. Plan. Control 2024, 36, 2009–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsamhi, S.H.; Ma, O.; Ansari, M.S.; Almalki, F.A. Survey on Collaborative Smart Drones and Internet of Things for Improving Smartness of Smart Cities. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 128125–128152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.; Diabat, A.; Sumari, P.; Gandomi, A.H. Applications, deployments, and integration of internet of drones (iod): A review. IEEE Sensors J. 2021, 21, 25532–25546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhatreh, H.; Sawalmeh, A.H.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Dou, Z.; Almaita, E.; Khalil, I.; Othman, N.S.; Khreishah, A.; Guizani, M. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A survey on Civil Applications and Key Research Challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 48572–48634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jońca, J.; Pawnuk, M.; Bezyk, Y.; Arsen, A.; Sówka, I. Drone-assisted monitoring of atmospheric pollution—A comprehensive review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooralishahi, P.; Ibarra-Castanedo, C.; Deane, S.; López, F.; Pant, S.; Genest, M.; Avdelidis, N.P.; Maldague, X.P. Drone-based non-destructive inspection of industrial sites: A review and case studies. Drones 2021, 5, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanpour, A.; Wang, T.; Vahidi-Shams, A.; Ectors, W.; Nakhaie, F.; Taheri, A.; Claudel, C. UAV-Based Intelligent Traffic Surveillance System: Real-Time Vehicle Detection, Classification, Tracking, and Behavioral Analysis. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.04624. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B.; Zhou, J.; Hong, Z.; Tang, J.; Huang, X. Vehicle Recognition and Driving Information Detection with UAV Video Based on Improved YOLOv5-DeepSORT Algorithm. Sensors 2025, 25, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.; Savkin, A.V. Strategies for optimized uav surveillance in various tasks and scenarios: A review. Drones 2024, 8, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastri, M.; Shrivastav, U. Optimizing Delivery Logistics: Enhancing Speed and Safety with Drone Technology. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.17253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.Y.; Park, K.; Kim, J.; Kim, J. Securing UAV flying base station for mobile networking: A review. Future Internet 2023, 15, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmaboud, A. The Internet of Drones: Requirements, Taxonomy, Recent Advances, and Challenges of Research Trends. Sensors 2021, 21, 5718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DJI Enterprise. Saving the Planet, One Renewable Energy Drone Inspection at a Time; DJI Enterprise: Shenzhen, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- SkyQuest Technology. Drones in Energy Sector Market Trends, Size, Share and Forecast 2032; SkyQuest Technology: Westford, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Derhab, A.; Cheikhrouhou, O.; Allouch, A.; Koubaa, A.; Qureshi, B.; Ferrag, M.A.; Maglaras, L.; Khan, F.A. Internet of drones security: Taxonomies, open issues, and future directions. Veh. Commun. 2022, 39, 100552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, G.K.; Gurjar, D.S.; Nguyen, H.H.; Yadav, S. Security threats and mitigation techniques in uav communications: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 112858–112897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; Gupta, R.; Tanwar, S. Blockchain envisioned UAV networks: Challenges, solutions, and comparisons. Comput. Commun. 2020, 151, 518–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altawy, R.; Youssef, A.M. Security, privacy, and safety aspects of civilian drones: A survey. ACM Trans. Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2016, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, V.; Pudi, V.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Elovici, Y. Security vulnerabilities of unmanned aerial vehicles and countermeasures: An experimental study. In Proceedings of the 2018 31st International Conference on VLSI Design and 2018 17th International Conference on Embedded Systems (VLSID), Pune, India, 6–10 January 2018; pp. 398–403. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan, R.A.; Emara, A.H.; Al-Sarem, M.; Elhamahmy, M. Internet of drones intrusion detection using deep learning. Electronics 2021, 10, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciancalepore, S.; Ibrahim, O.A.; Oligeri, G.; Di Pietro, R. PiNcH: An effective, efficient, and robust solution to drone detection via network traffic analysis. Comput. Netw. 2020, 168, 107044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Hernández, I.; Walter, T.; Alexander, K.; Clark, B.; Châtre, E.; Hegarty, C.; Appel, M.; Meurer, M. Increasing international civil aviation resilience: A proposal for nomenclature, categorization and treatment of new interference threats. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Technical Meeting of The Institute of Navigation, Reston, VA, USA, 28–31 January 2019; pp. 389–407. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, D.; Wu, H.; Jellinek, R.; Singh, V.; Ristenpart, T. Controlling UAVs with sensor input spoofing attacks. In Proceedings of the 10th {USENIX} Workshop on Offensive Technologies ({WOOT} 16), Austin, TX, USA, 8–9 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Blazy, O.; Bonnefoi, P.F.; Conchon, E.; Sauveron, D.; Akram, R.N.; Markantonakis, K.; Mayes, K.; Chaumette, S. An efficient protocol for UAS security. In Proceedings of the 2017 Integrated Communications, Navigation and Surveillance Conference (ICNS), Herndon, VA, USA, 18–20 April 2017; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rodday, N.M.; Schmidt, R.d.O.; Pras, A. Exploring security vulnerabilities of unmanned aerial vehicles. In Proceedings of the NOMS 2016-2016 IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium, Istanbul, Turkey, 25–29 April 2016; pp. 993–994. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, C.; Zhu, P. Defending against flooding attacks in the internet of drones environment. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Madrid, Spain, 7–11 December 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Salamh, F.E.; Karabiyik, U.; Rogers, M.; Al-Hazemi, F. Drone disrupted denial of service attack (3DOS): Towards an incident response and forensic analysis of remotely piloted aerial systems (RPASs). In Proceedings of the 2019 15th International Wireless Communications & Mobile Computing Sonference (IWCMC), Tangier, Morocco, 24–28 June 2019; pp. 704–710. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, S.; Yang, T.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, G. Survey of Attack Detection and Defense Technologies in Wireless Sensor Networks. In Advances in Intelligent Information Hiding and Multimedia Signal Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 440–447. [Google Scholar]

- Hassija, V.; Chamola, V.; Agrawal, A.; Goyal, A.; Luong, N.C.; Niyato, D.; Yu, F.R.; Guizani, M. Fast, reliable, and secure drone communication: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2021, 23, 2802–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleban, J.S.; Band, R.; Creutzburg, R. Hacking and securing the AR. Drone 2.0 quadcopter: Investigations for improving the security of a toy. In Proceedings of the Mobile Devices and Multimedia: Enabling Technologies, Algorithms, and Applications 2014, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2–6 February 2014; Volume 9030, pp. 168–179. [Google Scholar]

- Roder, A.; Choo, K.K.R.; Le-Khac, N.A. Unmanned aerial vehicle forensic investigation process: Dji phantom 3 drone as a case study. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.08649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.H.C.M.; da Silva, A.F. MELTWEB: A Transient Execution Attack to Capture Data in Fill Line Buffer. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2021, 20, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsard, C.; Massonet, P.; Dallons, G. Co-engineering security and safety requirements for cyber-physical systems. ERCIM News 2016, 106, 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Schmittner, C.; Ma, Z.; Schoitsch, E. Combined safety and security development lifecylce. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 13th International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN), Cambridge, UK, 22–24 July 2015; pp. 1408–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Sojka, M.; Kreč, M.; Hanzálek, Z. Case study on combined validation of safety & security requirements. In Proceedings of the 9th IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Embedded Systems (SIES 2014), Pisa, Italy, 18–20 June 2014; pp. 244–251. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC 27001; Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Information Security Management Systems—Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Li, Z.; Tang, Z.; Lv, J.; Li, H.; Han, W.; Zhang, Z. An information security risk assessment method for cloud systems based on risk contagion. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 5th Information Technology and Mechatronics Engineering Conference (ITOEC), Chongqing, China, 12–14 June 2020; pp. 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Selby, N.; Adib, F. Drone relays for battery-free networks. In Proceedings of the Conference of the ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 21–25 August 2017; pp. 335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Sindre, G.; Opdahl, A.L. Eliciting security requirements with misuse cases. Requir. Eng. 2005, 10, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 27000; Information Technology—Security Techniques—Information Security Management Systems—Overview and Vocabulary. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Lei, Y.; Zeng, L.; Li, Y.X.; Wang, M.X.; Qin, H. A lightweight authentication protocol for UAV networks based on security and computational resource optimization. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 53769–53785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, W.; Kou, L.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, L.; Da, Q.; Chen, L. A data authentication scheme for UAV ad hoc network communication. J. Supercomput. 2020, 76, 4041–4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, S.U.; Abbasi, I.A.; Algarni, F. A key agreement scheme for IoD deployment civilian drone. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 149311–149321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, S.U.; Abbasi, I.A.; Algarni, F. A mutual authentication and cross verification protocol for securing Internet-of-Drones (IoD). Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 72, 5845–5869. [Google Scholar]

- Rios, J.L.; Jung, J.; Johnson, M.A. Non-Repudiation for Drone-Related Data; NASA Technical Reports Server: Hampton, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo, M.; Zhang, J. Efficient, traceable and privacy-aware data access control in distributed cloud-based IoD systems. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 45206–45221. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.L.; Deng, Y.Y.; Weng, W.; Chen, C.H.; Chiu, Y.J.; Wu, C.M. A traceable and privacy-preserving authentication for UAV communication control system. Electronics 2020, 9, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, B.; Das, A.K.; Sutrala, A.K. Private blockchain-based access control mechanism for unauthorized UAV detection and mitigation in Internet of Drones environment. Comput. Commun. 2021, 166, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ullah, I.; Kumar, N.; Oubbati, O.S.; Qureshi, I.M.; Noor, F.; Khanzada, F.U. An efficient and secure certificate-based access control and key agreement scheme for flying ad-hoc networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 4839–4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrepati, R.R.; Guntur, S.R. DroneMap: An IoT network security in internet of drones; Development and Future of Internet of Drones (IoD): Insights, Trends and Road Ahead; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, E.K.; Chen, C.M.; Wang, F.; Khan, M.K.; Kumari, S. Joint-learning segmentation in Internet of drones (IoD)-based monitor systems. Comput. Commun. 2020, 152, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghelani, J.; Gharia, P.; El-Ocla, H. Gradient Monitored Reinforcement Learning for Jamming Attack Detection in FANETs. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 23081–23095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.; Alasmary, H.; Kumar, N.; Nayak, A. Saaf-iod: Secure and anonymous authentication framework for the internet of drones. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 73, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, A.; Chaudhry, S.A.; Ghani, A.; Bilal, M. A secure blockchain-oriented data delivery and collection scheme for 5G-enabled IoD environment. Comput. Netw. 2021, 195, 108219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cracknell, A.P. UAVs: Regulations and law enforcement. Int. J. Remote. Sens. 2017, 38, 3054–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, G.; Senthivel, S.G.; Balaganesh, S.; Rajakumar, B.R.; Ravichandran, V.; Guizani, M. MLB-IoD: Multi Layered Blockchain Assisted 6G Internet of Drones Ecosystem. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 72, 2511–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Jan, M.A.; Jolfaei, A.; Xu, M.; He, X.; Chen, J. A distributed and anonymous data collection framework based on multilevel edge computing architecture. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 16, 6114–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, C.; Rahul, K. Efficient QoS provisioning using SDN for end-to-end data delivery in UAV assisted network. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Networks and Telecommunications Systems (ANTS), Goa, India, 16–19 December 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, Z.; Raza, B.; Shah, H.; Khan, S.; Waheed, A. Towards blockchain-based secure storage and trusted data sharing scheme for IoT environment. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 36978–36994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinche, S.; Polo, O.; Raposo, D.; Femandes, M.; Boavida, F.; Rodrigues, A.; Pereira, V.; Silva, J.S. Assessing redundancy models for IoT reliability. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 19th International Symposium on “A World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks” (WoWMoM), Chania, Greece, 12–15 June 2018; pp. 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, S.; Singh, A.; Batra, S.; Kumar, N.; Yang, L.T. UAV-empowered edge computing environment for cyber-threat detection in smart vehicles. IEEE Netw. 2018, 32, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Hu, L.; Zhou, J.; Hu, J.; Zhao, K. A semantics-based approach to multi-source heterogeneous information fusion in the internet of things. Soft Comput. 2017, 21, 2005–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesenko, H.; Kharchenko, V.; Sachenko, A.; Hiromoto, R.; Kochan, V. An Internet of Drone-based multi-version post-severe accident monitoring system: Structures and reliability. In Dependable IoT for Human and Industry; River Publishers: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2022; pp. 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Prates, N.; Vergütz, A.; Macedo, R.T.; Santos, A.; Nogueira, M. A defense mechanism for timing-based side-channel attacks on IoT traffic. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2020-2020 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 7–11 December 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gangolli, A.; Mahmoud, Q.H.; Azim, A. A machine learning approach to predict system-level threats from hardware-based fault injection attacks on iot software. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual International Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering, Toronto, ON, Canada, 15–17 November 2022; pp. 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Samanth, S.; KV, P.; Balachandra, M. CLEA-256-based text and image encryption algorithm for security in IOD networks. Cogent Eng. 2023, 10, 2234123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, W.J.; Chang, J.C.; Chen, C.L. A highly secure IoT firmware update mechanism using blockchain. Sensors 2022, 22, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehret, A.; Del Rosario, E.; Gettings, K.; Kinsy, M.A. A hardware root-of-trust design for low-power soc edge devices. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE High Performance Extreme Computing Conference (HPEC), Waltham, MA, USA, 22–24 September 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, G. Unmanned aerial vehicles: Emerging policy and regulatory issues. J. Law Inf. Sci. 2013, 22, 201–236. [Google Scholar]

- Alladi, T.; Chamola, V.; Naren; Kumar, N. PARTH: A two-stage lightweight mutual authentication protocol for UAV surveillance networks. Comput. Commun. 2020, 160, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Yin, X.; Wang, X.; Hu, J. A review on security issues and solutions of the internet of drones. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2022, 3, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solangi, Z.A.; Solangi, Y.A.; Chandio, S.; bt. S. Abd. Aziz, M.; bin Hamzah, M.S.; Shah, A. The future of data privacy and security concerns in Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Innovative Research and Development (ICIRD), Bangkok, Thailand, 11–12 May 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Laszka, A.; Abbas, W.; Vorobeychik, Y.; Koutsoukos, X. Integrating redundancy, diversity, and hardening to improve security of industrial internet of things. Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2020, 6, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeiros, J.B.; Chimuco, F.T.; Samaila, M.G.; Freire, M.M.; Inácio, P.R. Attack and system modeling applied to IoT, cloud, and mobile ecosystems: Embedding security by design. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2020, 53, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeal, G.S. Drones and the future of aerial surveillance. Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 2016, 84, 354. [Google Scholar]

- Karaca, Y.; Cicek, M.; Tatli, O.; Sahin, A.; Pasli, S.; Beser, M.F.; Turedi, S. The potential use of unmanned aircraft systems (drones) in mountain search and rescue operations. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 36, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, L.D.P.; Guerriero, F.; Macrina, G. Using drones for parcels delivery process. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 42, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levner, E.; Tsadikovich, D. Fast Algorithm for Cyber-Attack Estimation and Attack Path Extraction Using Attack Graphs with AND/OR Nodes. Algorithms 2024, 17, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arat, F.; Akleylek, S. Attack path detection for IIoT enabled cyber physical systems: Revisited. Comput. Secur. 2023, 128, 103174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Salili, Z.A.; Al Ghamdi, G.S.; Al Ibrahim, N.; Alesse, R.A.; Saqib, N.A. A Comprehensive Analysis of Security Dimensions within the Growing Sphere of the Internet of Drones (IoD). In Proceedings of the 2024 Seventh International Women in Data Science Conference at Prince Sultan University (WiDS PSU), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 3–4 March 2024; pp. 176–182. [Google Scholar]

- Sezgin, A.; Boyacı, A. Rising Threats: Privacy and Security Considerations in the IoD Landscape. J. Aeronaut. Space Technol. 2024, 17, 219–235. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Wang, J.; Yu, G.; Guo, W.; Domeniconi, C.; Guo, M. Directed acyclic graph learning on attributed heterogeneous network. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 10845–10856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaila, M.G.; Sequeiros, J.B.; Simoes, T.; Freire, M.M.; Inacio, P.R. IoT-HarPSecA: A framework and roadmap for secure design and development of devices and applications in the IoT space. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 16462–16494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, G. Cybersecurity Risk Management Process for Unmanned Aerial Systems (Uas) at the Strategic Level. Ph.D. Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkels, A.; Gronvall, B.; Voigt, T. Contiki-a lightweight and flexible operating system for tiny networked sensors. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual IEEE International Conference on Local Computer Networks, Tampa, FL, USA, 16–18 November 2004; pp. 455–462. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood, R.T.; Ahmed, G.; Siddiqui, S. Simulating ML-based intrusion detection system for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) using COOJA simulator. In Proceedings of the 2022 16th International Conference on Open Source Systems and Technologies (ICOSST), Lahore, Pakistan, 14–15 December 2022; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, S.; Shafaei, S.; Jones, T.S.; Totaro, M.W. Secure Communication in Drone Networks: A Comprehensive Survey of Lightweight Encryption and Key Management Techniques. Drones 2025, 9, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delligatti, L. SysML Distilled: A Brief Guide to the Systems Modeling Language; Addison-Wesley Professional: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, B.T.; Bakirtzis, G.; Elks, C.R.; Fleming, C.H. Cyber-Physical Systems Modeling for Security Using SysML. In Proceedings of the Systems Engineering in Context, Charlottesville, VA, USA, 8–9 May 2019; pp. 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, N.U.I.; Lutfi, M.; Ahmed, I.; Akundi, A.; Cobb, D. Modeling and Analysis of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle System Leveraging Systems Modeling Language (SysML). Systems 2022, 10, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Zheng, J.; He, T.; Wei, S.; Shan, C.; Hu, C. B-uavm: A blockchain-supported secure multi-uav task management scheme. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 21240–21253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xu, J.; Fu, Y.; Tian, W. Security Analysis of UAV Swarm Based on Smart Contracts. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Robotics (ICICR), Dalian, China, 12–14 April 2024; pp. 46–51. [Google Scholar]

| Certification | IoD Specific | Context Adaptive | Risk Assess. | Risk Propag. | Threat Model | Sec. Req. Eng. | Maturity Levels | Lifecycle Coverage | Tool Support | Open Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common Criteria | – | – | ○ | – | ◐ | ◐ | ● | ○ | – | ● |

| ICSA Labs | – | – | ● | – | ◐ | ○ | ● | ◐ | – | – |

| ARMOUR | – | ○ | ◐ | – | ◐ | ○ | ● | ◐ | ◐ | – |

| DSPSMA | – | ○ | ◐ | – | ◐ | – | ○ | ◐ | ○ | ○ |

| SORA | ○ | ◐ | ◐ | – | ○ | – | ● | ○ | – | ● |

| GCACS-IoD | ● | – | ◐ | – | – | ◐ | – | – | – | ○ |

| Manna SafeIoD | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Characteristic | IoD | Cellular | Vehicular (VANET) | WSN | UWSN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Node Velocity | Rapid (>15 m/s) | Low mobility (<5 m/s) | Variable (Urban: ≈8 m/s; Highway: >20 m/s) | Quasi-static (Dependent on host) | Slow (Driven by water currents) |

| Mobility Pattern | Mission-dependent (3D) | Stochastic/Random | Constrained by road infrastructure | Mostly Random | Dictated by fluid dynamics |

| Verticality (Altitude) | Significant variation | Negligible | Negligible | Negligible | Significant variation |

| Topology Dynamism | High | High | High | Low | Low |

| Computational Capacity | Moderate | High | High | Limited | Limited |

| Power Limitations | Critical | Moderate | Relaxed | Critical | Critical |

| Entity | Description |

|---|---|

| Malicious Agent | Adversarial actor seeking to identify exploitable vulnerabilities. Ranges from nation-state actors with electronic warfare capabilities to opportunistic criminals using readily available attack tools. |

| IoD Device | Most vulnerable component serving as entry point. Encompasses drones, communication links, ground control stations, and supporting infrastructure with inherent resource constraints. |

| Actual Target | Critical system or asset the attacker ultimately seeks to compromise, including critical infrastructure, sensitive data repositories, or command systems beyond the immediate drone network. |

| Category | Sub-Category | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Communication | Constrained-peer | D2D comms under energy/computational limits preventing robust security |

| Non-constrained | Traditional vulnerabilities + mobile platforms/dynamic topology | |

| Environment | Within-zone | Restricted movements; attackers exploit flight patterns/airspace constraints |

| Inter-zone | Zone transitions via gates; vulnerabilities during handoff/boundary crossings | |

| Provider | ZSP-related | Ground-based control system vulnerabilities |

| Cloud-related | Targets: metadata, performance characteristics, operational parameters, ACL | |

| Drone | Dual-role | Both attack victims and tools; compromised units attack other components |

| Activity | Input | Technique | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualify Mission Type | Operational profile, context model, mission objectives | Classification heuristics, risk correlation | Categorized list of IoD mission types and associated critical assets |

| Identify Threats | Mission types, preliminary asset list | Misuse cases, threat modeling | Structured list of threats (communication, environment, drone-specific) |

| Identify Endpoint Hardware | Drone architecture, control station infrastructure, vendor documentation | Device profiling, authentication validation | Verified list of hardware endpoints and trusted vendors |

| Identify Sensors data | Types of onboard sensors, communication channels (e.g., RF, LTE, 5G) | Protocol analysis, communication stack mapping | List of sensor types and their associated transmission protocols |

| Elicit Security Requirements | Output of all preceding activities step 1 to step 4 | Structured analysis based on mandatory categories | Finalized list of security requirements |

| Category | Requirement | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| Authentication | Lightweight Authentication Schemes | [92] |

| Data Integrity and Authenticity | [93] | |

| Key Distribution and Management | [94] | |

| Mutual Authentication | [95] | |

| Non-Repudiation | [96] | |

| Access Control | Fine-grained | [97] |

| Privacy-preserving | [98] | |

| Environment transparency | [99] | |

| Secure Certificate | [100] | |

| Network Security | Network isolation | [101] |

| Timeliness | [102] | |

| Availability (jamming, DoS, etc.) | [103] | |

| Overhead minimization | [104] | |

| Mobile transmission security | [105] | |

| Security policy enforcement | [106] | |

| Blockchain approach | [107] | |

| Data Security | Anomalization techniques | [108] |

| Data flow control | [109] | |

| Secure external data storage | [110] | |

| Data loss mitigation | [97] | |

| Data encryption | [2] | |

| Resilience | Continuous operation | [111] |

| Operation intermittent | [111] | |

| Monitoring | Threat detection and response | [112] |

| Handle heterogeneous sources | [113] | |

| Infrastructure monitoring | [114] | |

| Physical Security | Side-Channel detection | [115] |

| Fault injection detection | [116] | |

| Encryption Engines | [117] | |

| Firmware Protection | [118] | |

| Hardware-Based Roots of Trust | [119] | |

| Regulation | Security policy enforcement | [106] |

| Protection legislation compliance | [120] | |

| Standard compliance | [106] |

| Field | Type | Valid Values | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| domain | Enum | {Agriculture, Surveillance, Delivery, Inspection, Emergency, Military, Other} | Application domain |

| phase | Enum | {Development, Operational} | System lifecycle phase |

| device_type | Enum | {Drone, ZSP, Gateway, GCS, Cloud} | IoD component category |

| mission_criticality | Integer | [1–5] | 1 = Low, 5 = Critical |

| data_sensitivity | Enum | {Non-Sensitive, PII, Critical} | Data classification level |

| stores_data | Boolean | {true, false} | Local data storage capability |

| cloud_integration | Boolean | {true, false} | Cloud service dependency |

| zsp_interaction | Enum | {None, Periodic, Continuous} | ZSP communication frequency |

| regulatory_framework | List[Enum] | {FAA, EASA, ANAC, GDPR, LGPD, ISO27001, MIL-STD} | Applicable regulations |

| environment | Enum | {Indoor, Urban, Rural, Maritime, Military} | Deployment environment |

| airspace_class | Enum | {Controlled, Uncontrolled, Restricted} | Airspace classification |

| Field | Type | Valid Values | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| device_id | String | UUID format | Unique device identifier |

| manufacturer | String | Free text | Device manufacturer |

| model | String | Free text | Device model designation |

| firmware_version | String | Semantic versioning | Current firmware version |

| comm_protocols | List[Enum] | {WiFi, LTE, 5G, LoRa, ADS-B, MAVLink} | Supported protocols |

| sensors | List[Enum] | {GPS, Camera, LIDAR, Altimeter, IMU, Thermal} | Onboard sensors |

| compute_class | Enum | {Constrained, Moderate, High} | Computational capability |

| has_tpm | Boolean | {true, false} | Hardware security module presence |

| has_secure_boot | Boolean | {true, false} | Secure boot capability |

| encryption_support | List[Enum] | {AES-128, AES-256, ChaCha20, ECC, RSA} | Supported cryptographic algorithms |

| Field | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| threat_id | String | Unique threat identifier (e.g., IOD-COMM-001) |

| category | Enum | {Communication, Environment, Drone, Provider, Physical, Cyber} |

| subcategory | String | Specific threat classification (e.g., Jamming, Spoofing) |

| cvss_base | Float [0.0–10.0] | CVSS v3.1 Base Score |

| cvss_vector | String | CVSS vector string (e.g., AV:N/AC:L/PR:N/UI:N/S:U/C:H/I:H/A:H) |

| applicable_devices | List[Enum] | Device types vulnerable to this threat |

| applicable_protocols | List[Enum] | Protocols through which threat manifests |

| mitigating_controls | List[String] | Security control identifiers that mitigate this threat |

| propagation_factor | Float [0.0–1.0] | Likelihood of lateral propagation ( coefficient base) |

| Threat ID | Category | Subcategory | CVSS | Applicable Devices | Mitigating Controls | Prop. Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOD-COMM-001 | Communication | GPS Spoofing | 8.1 | Drone, GCS | SC-AUTH-003, SC-NET-007 | 0.3 |

| IOD-CYBER-003 | Cyber | Firmware Tampering | 9.0 | Drone, ZSP, Gateway | SC-PHY-004, SC-PHY-005 | 0.7 |