1. Introduction

The transition to battery electric vehicles (BEVs) is paving the way for major changes in the automotive industry [

1]. The change in vehicle architecture enables a major redesign of critical subsystems aimed at developing innovative systems and technologies with the goal of improving safety, efficiency, and passenger comfort [

2,

3,

4]. One of the most attractive and challenging features of BEVs is the potential for integration of in-wheel-motors (IWMs) [

5,

6]. These allow for increased efficiency thanks to optimal control of the share of regenerative versus friction braking torque [

7,

8,

9]. In this context, brake-by-wire (BBW) systems enable the decoupling of the brake pedal from the effective braking action provided by the calipers, facilitating smooth blending of braking torques [

10,

11,

12]. Recent studies have further emphasized the importance of one-box electro-hydraulic systems, which integrate electric boosters and wheel-cylinder modules into a compact architecture, providing enhanced control and size benefits [

13,

14]. However, distributed BBW, i.e., a braking system which consists of four independent braking actuators (one per each corner), leads to the possibility of independently controlling each corner. This enables better integration of vehicle dynamics control systems, enhancing vehicle performance [

15,

16].

In [

17] a comprehensive overview of the main types of BBW actuators is provided: an electro-mechanical brake (EMB) is the best solution in terms of performance, while an electro-hydraulic brake (EHBs) holds an advantage thanks to the higher technological maturity [

18]. Studies show that BBWs are faster, more accurate, and more flexible than traditional braking systems. For example, the response time of a BBW system is 150

, which represents a reduction of 30% compared to traditional systems [

2]. The higher proportion of active control suggests the control algorithm as the key factor for the precise and rapid adjustment of braking pressure, aiming at friction compensation to address nonlinearities [

19,

20,

21], and at performance adjustment based on the driving style [

22,

23] sensed through the brake pedal sensor (BPS) [

10]. A number of contributions have focused on the optimization of centralized and distributed BBW systems: ref. [

24] focuses on the optimization of the booster motor driving centralized EHB systems; ref. [

25] focuses on linear and nonlinear optimization of EHB, EMB, and electro-wedge brake (EWB) control strategies; ref. [

26] provides optimization and the robust design of an EWB; and ref. [

27] provides a methodology for the design optimization of cam profiles in EMBs through particle swarm optimization.

The existing literature does not distinguish between the two fundamentally different phases of a braking event—namely, pad–disc gap closure and hydraulic pressure build-up—nor does it provide an integrated sizing methodology for the electro-mechanical and hydraulic subsystem. In addition, the distributed electro-hydraulic architecture, in which each wheel is equipped with an independent hydraulic actuator, has received limited attention from a design-optimization perspective.

Given the advantages of EHBs over EMBs and EWBs, this paper focuses on optimizing the design of a distributed EHB (DEHB) system like the one in

Figure 1, this being the best compromise in terms of performance level and technological maturity. The aim is to obtain the best trade-off between power consumption and braking performance, ultimately increasing the system’s overall efficiency. The mathematical model of the system accounts for two different phases of the braking event (the pads’ motion to reach the disc and the pressure build-up, namely Phase A and B, respectively). Such a mathematical model is then leveraged by a computational model to retrieve the relevant performance indicators. The optimization problem is set up by choosing the model parameters with the greatest impact as design variables by means of a sensitivity analysis. The cost function considers the efficiencies of the two transmissions as a function of the design variables and structural parameters. A genetic algorithm (GA) is then employed to solve the constrained optimization problem, thanks to its capability of working in complex and nonlinear search spaces. Once the optimized value of the design variables is obtained, the optimal solution is evaluated by comparing it with different commercially available electric motors to assess the optimization procedure’s benefits. Finally a dynamic analysis of the system during longitudinal braking maneuvers highlights the most important pros and cons of a distributed BBW solution for passenger car applications.

The novelty of the work lies in the development of a physics-based optimization framework, which has been specifically tailored to distributed electro-hydraulic systems and is able to simultaneously consider motor, transmission, and hydraulic parameters. Furthermore, while previous contributions mainly evaluated actuator performance at the component level, the present work integrates vehicle-level simulations, thereby linking the preliminary design to energy consumption and dynamic performance under realistic operating conditions.

2. Distributed Electro-Hydraulic Brake Model

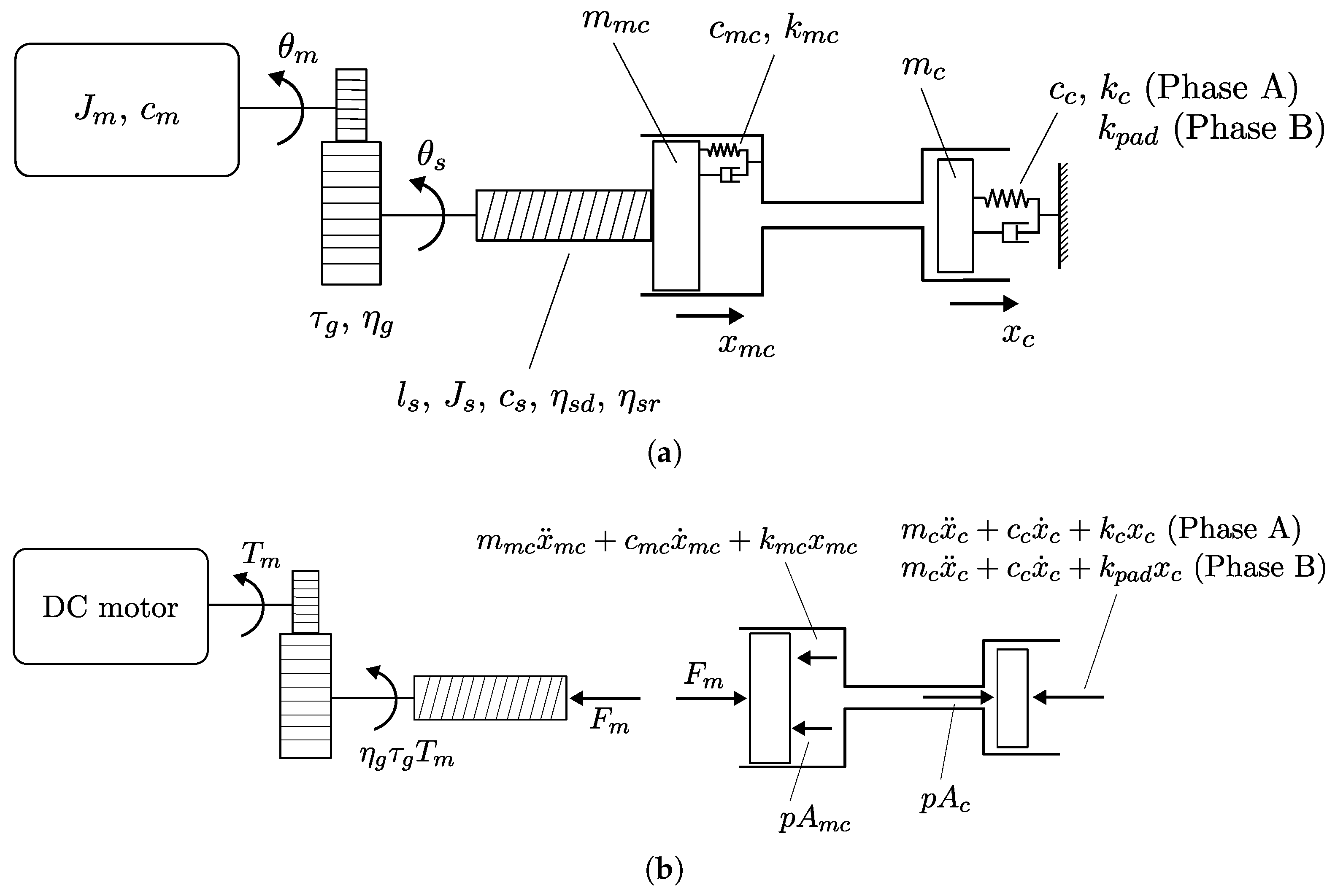

Figure 1 shows a schematization of a single EHB system. A DC motor (1) drives a gearbox (2), responsible for increasing the torque and reducing speed. Rotational motion is then converted to axial motion by means of a ball screw (3), leading to the displacement of the piston in the master cylinder (4). Finally, the hydraulic pipeline (5) delivers pressurized fluid to the brake caliper (7), displacing the brake pistons (8) and thus the brake pads. Due to the distributed nature of the system, each wheel corner is equipped with a complete system identical to the one previously described. In other words, the full setup is implemented independently at each corner. The mechanical model of the proposed solution is shown in

Figure 2a, and is equipped with a brushed DC motor, owing to its modeling and control simplicity.

Following the representation in

Figure 2a, a comprehensive mathematical model of the system can be developed for each of the two phases: (Phase A) clear the gap between pads and disc, and (Phase B) develop braking pressure.

Phase A is characterized by rapid displacement of the pad to fill the pad–disc clearance. Given the brief duration available to accelerate inertias, this is the most crucial part of the braking event in terms of required power. Since the purpose of the hydraulic fluid is only to displace the brake pads, the relative pressure does not exceed

bar. This makes it possible to neglect oil compressibility, which in turn means that the motion of the master cylinder piston only depends on the volume of fluid put into motion. The volume of hydraulic fluid inside the caliper (

) is computed as the product of number (

), cross section (

), and displacement (

) of the brake pistons. Since the fluid can be considered incompressible, continuity equations hold, thus the volume displaced in the caliper can be considered to be equal to volume exiting the master cylinder, with the latter being the product of master cylinder displacement (

) and area (

). The system reduces to a single degree of freedom (DoF), and the coupling between displacement of caliper piston and master cylinder is described by Equation (1).

The power balance approach can then be applied to the motor, master cylinder, and caliper piston, considering the forces reported in

Figure 2b. Since the system has a single DoF, the states of the motor and caliper piston can be written as functions of the master cylinder states, yielding Equation (2).

The generalized inertia, damping, and stiffness terms at the master cylinder during Phase A are defined in Equation (3). The contributions to inertia (Equation (3a)) and damping (Equation (3b)) are: motor (

,

), ball screw (

,

), master cylinder (

,

), and caliper piston (

,

). Stiffness terms (Equation (3c)) are related to the master cylinder’s (

) and caliper pistons’ oil-scrapers.

By manipulation of the forcing term in Equation (2), Equation (4a) is obtained, where

and

. The latter is then coupled with Equation (4b), which describes motor dynamics, to obtain the equations of motion for the electro-mechanical system during Phase A.

Phase B starts after the pad makes contact with the disc. Due to the high stiffness of the pads, displacement and velocities become close to zero. Relevant pressure is built up in the hydraulic circuit, making invalid the incompressibility assumption. Thus, conversely to what was the case in Phase A, separate dynamics for the master cylinder (Equation (5a)) and caliper piston (Equation (5b)) have to be considered. The two are coupled by Equation (5c), which models pressure dynamics. The equation of motion for the electro-mechanical system is obtained through coupling with the motor dynamics (Equation (5d)), yielding the following:

and are the generalized inertia and damping coefficients, respectively, which account for the motor, screw, and master cylinder. This highlights that the two parts of the system (motor plus master cylinder, and calipers) are described by two separate equations (Equation (5a) and Equation (5b), respectively) and coupled through the hydraulic fluid pressure.

The proposed mathematical model focuses on capturing the dominant electro-mechanical and hydraulic effects that are relevant for actuator sizing and optimization. High-frequency dynamics and strongly nonlinear phenomena such as brake pad thermal fade, hydraulic dynamics, or nonlinear seal friction are neglected since they depend on the design of the caliper, which is not subject of the optimization.

3. Optimization

In this section, optimization of the DEHB is discussed. The mathematical model is leveraged to compute the relevant outputs through an optimization framework. The GA then makes it possible to span the design space, in search of the optimal solution. The aim of the optimization is to provide a design for the system in terms of master cylinder size, transmission (i.e., gearset and ball screw) characteristics, and motor parameters. Calipers are not subject to optimization since their sizing is carried out during the design of the overall braking system. Different indicators are employed to characterize performance of the system. In particular, response time has considerable relevance since it is a safety-critical indicator. Maximum current and torque have high importance in the choice of electric motor. Finally, the required electric power should be optimized to reduce consumption and increase the efficiency of the vehicle.

3.1. Optimization Framework

The optimization framework characterizes the system’s mechanical and electrical behavior by mapping structural parameters to performance metrics. The workflow followed by the algorithm is detailed below.

The maximum pressure that must be provided by the braking system directly affects the maximum torque to be delivered by the DC motor. In particular Equations (5a)–(5c) can be written in steady-state conditions. Equation (7) shows the relationship between required pressure and axial force on the master cylinder, which depends on the bulk modulus and displaced volume of hydraulic fluid, spring stiffness, the pre-compression area of the master cylinder, and area and number of the caliper cylinders.

The latter can then be related to the equivalent torque at the motor through the transmission ratios and the efficiencies of the gearset and ball screw as follows:

Equations (7) and (8) allow for the computation of the necessary torque for a certain pressure level. This value can then be used to avoid oversizing the motor, by setting it as the setpoint for the maximum torque during Phase A, hence ensuring complete exploitation of the entire operating range of the motor during both phases of the braking event.

To introduce indicators of electrical performance into the framework, the motor has been parametrized as a function of rotor diameter (

), rotor length (

), and number of windings (

). This makes it possible to gain an insight into the preliminary sizing of the DC motor. In particular, rotor inertia can be immediately computed as in Equation (9), where

is the rotor density considering a composition of

steel and

copper.

This makes it possible to compute generalized inertia (), damping (), and stiffness () of the motor during Phase A, as stated in Equations (3a)–(3c). These values will then be used in the following steps to solve the equations of motion for the aforementioned phase.

The determination of the time needed to fill the pad–disc clearance, namely the time to contact (

), is the most crucial part of the design phase, due to the small amount of time available to accelerate inertias. In order to have a DC motor that is completely exploited during both Phase A and B, the design choice to have the same maximum torque for the two phases was made. Otherwise, one of the two phases could require a higher torque, leading to a motor that is oversized during one part of the braking event. The caliper piston’s motion time history can then be imposed as a piecewise constant since: (a) the pad–disc clearance is known, and (b) the clearance must be filled in the shortest amount of time, while ensuring a null final velocity to avoid pressure overshoot. Equation (4a) can then be solved for the time to contact. The result is the minimum time that ensures the clearance to be filled with a null final velocity, while requiring a maximum torque equal to the one necessary to provide

in steady-state conditions. Notice that, until now, the time to contact was only dependent on structural parameters and on maximum pressure, without any constraint on its maximum value. This will be tackled in

Section 3.3, where a constraint on the maximum value will be introduced in the optimization algorithm to guarantee fast responsiveness.

The design requires the maximum voltage to be 12 V, since the DEHB system must be powered directly by the vehicle’s low-voltage battery. The voltage is described by Equation (5d) in steady-state conditions, where electrical parameters can be approximated as reported in Equations (10a)–(10c).

where

,

is the minimum wire diameter able to withstand the maximum current, and

is a correction factor for magnetic flux density

in order to account for the different orientation of the windings with respect to the magnetic flux.

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

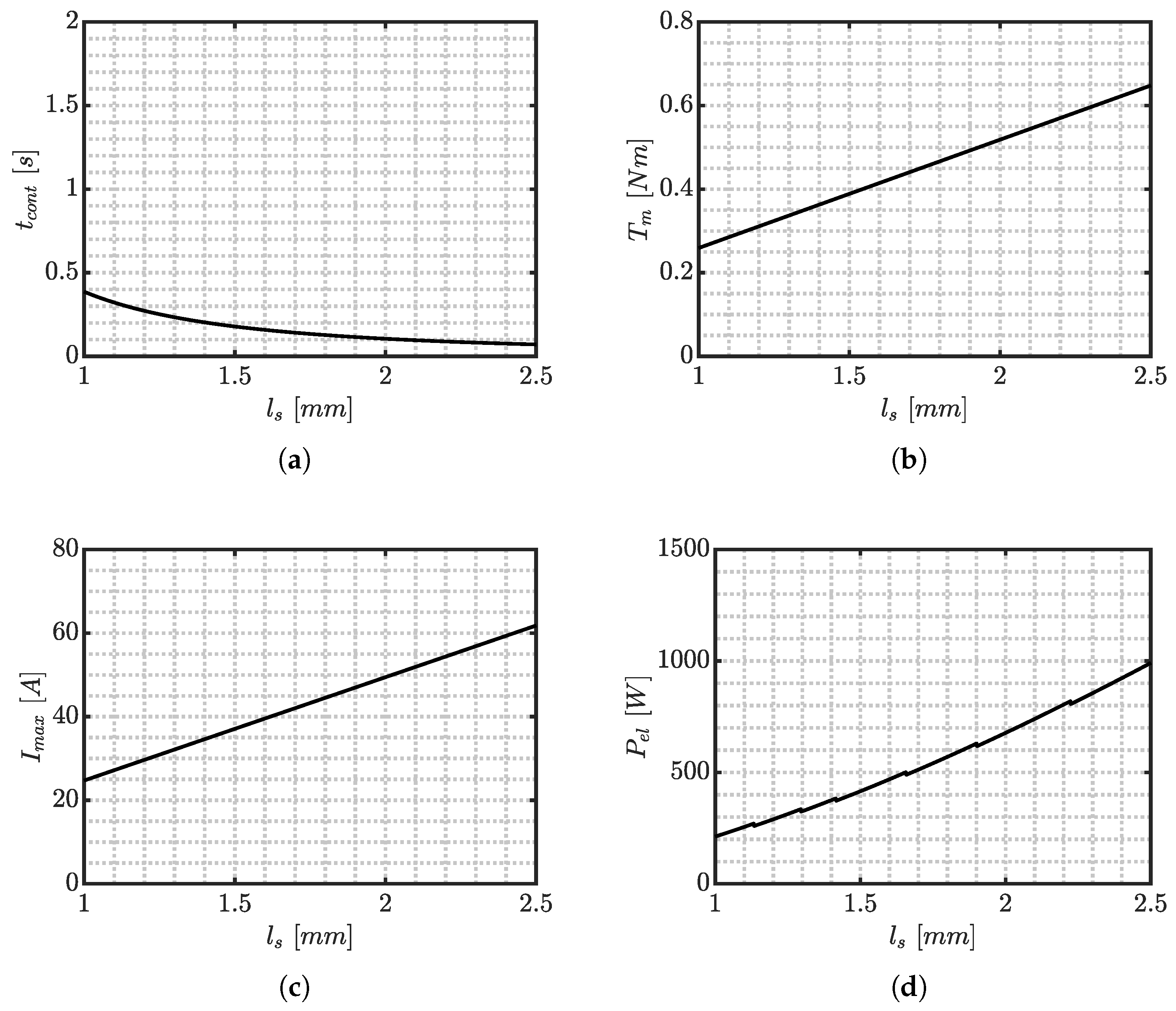

The sensitivity analysis allows to assess the most influential variables, as well as to gain an insight into where the optimal value of each design variable could be located. Due to the large number of variables, it was conducted by varying only one parameter at a time.

The master cylinder’s diameter plays the most important role: it increases the displacement needed to fill pad–disc clearance decreases leading to a lower time to contact (

Figure 3a). On the other hand, torque, as stated in Equation (7), increases due to the greater axial force needed to ensure maximum pressure (

Figure 3b,c). Current is proportional to torque since motor parameters (hence the torque constant) are kept fixed. Finally,

Figure 3d reports the behavior of the electric power, which increases with the diameter due to the increased inertia.

The ball screw lead and gearbox transmission ratio are closely related to peak torque and power. Their combination contributes to the overall transmission ratio and thus influences the size of the required DC motor. With an increasing lead for the ball screw (i.e., for the transmission ratio), the time to contact decreases while the maximum torque increases (

Figure 4a,b). Once again, the motor parameters are kept constant, thus the current is proportional to the torque (

Figure 4c).

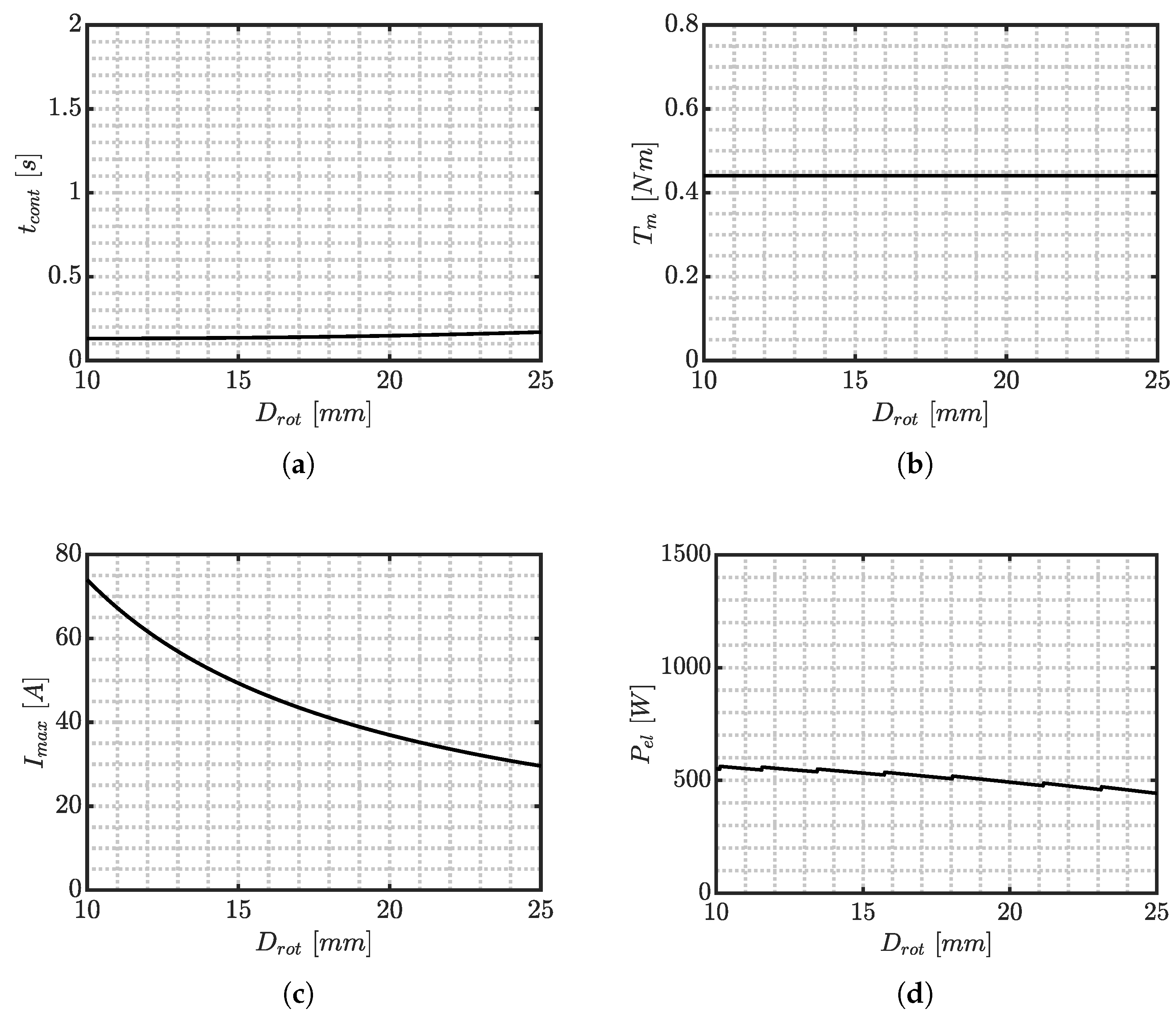

Electrical parameters (i.e., motor diameter, length, and number of coils) are strictly related to the maximum current due to their influence on the torque constant.

Figure 5c shows that maximum current decreases with an increasing rotor diameter. This is consistent with the increase in the torque constant (Equation (10c)).

3.3. Optimization Problem

The identified design variables, shown in

Table 1, were optimized through a GA. The GA was chosen thanks to its robustness and its ability to discover good solutions for difficult and highly-dimensional problems. Moreover it can easily handle highly nonlinear objective functions and multiple constraints through penalization, making it a suitable choice for braking system optimization [

28,

29]. The design space for each variable is summarized in

Table 1.

The objective functions (OFs) to be minimized are time to contact, maximum current, maximum torque, and peak power. The first one makes it possible to penalize systems with lower responsiveness. Current and torque ensure feasible sizing of the DC motor, as well as safe and reliable operation thanks to the lower maximum current. Peak power is used as an indicator of the overall consumption, which is crucial in improving the overall efficiency of the vehicle.

The cost function is then reported within Equation (11), where min–max normalization and weighting are used as follows:

Penalization is applied to the solutions that do not respect the following constraints:

The GA was run with a population of

individuals, which are coded in binary strings of

bits. Mutation with a probability of

and single-point crossover are applied to ensure diversity, and roulette wheel selection makes it possible to form the offspring depending on the fitness. The algorithm was iterated until convergence multiple times, and the optimal solution was consistently located within the same neighborhood. The results are reported within

Table 2a,b.

3.4. Comparison with Commercial Motors

A comparison with different commercial motors is summarized in

Table 3, where

and

have been approximated starting from the rotor dimensions computed through the optimization framework. The aim is to assess the feasibility of the proposed solution by comparing the main constructive parameters.

The optimized motor presents parameters that are comparable with commercially available DC motors, except for resistance and length, which are smaller. The optimized solution results in a more compact machine, especially in terms of length. It should be noted that the reduced motor size may be due to excessive simplifications in the relationship between rotor geometry and electrical properties, which would require a more thorough investigation of the space occupied by the windings layout. Nevertheless, the results are consistent with the fact that flat motors, i.e., motors with a high diameter-to-length ratio, are typically chosen for high-torque applications.

4. Performance Evaluation

The aim of this section is to quantify the results of the optimization procedure. At first, the quality of the approximated solution is evaluated by comparing the results with a high-fidelity multiphysics model. Following the dynamic behavior of the DEHB when coupled with vehicle dynamics control logics is investigated and, lastly, the performance is compared with a non-optimized solution. It should be noted that the multiphysics model is not intended as an experimentally validated reference, but as an independent modeling technique which incorporates additional effects and can be used to assess the robustness of the proposed optimization framework.

4.1. Comparison with the Multiphysics Model

The multiphysics model was developed in the MATLAB R2024b/Simulink/Simscape environment, allowing for comprehensive dynamic simulations of the entire system. The model integrates a permanent-magnet DC motor, whose voltage is provided by means of a controlled voltage source. A current sensor was introduced to measure the armature current. The DC motor drives a gearset, which is rigidly connected to a leadscrew. The axial motion of the leadscrew is then fed to an hydraulic cylinder, which represents the master cylinder. Oil scraper stiffness and damping have been modeled as lumped. The hydraulic cylinder is connected to the hydraulic circuit through an isothermal interface, which delivers hydraulic fluid through a rigid-walled pipe. The displaced fluid finally enters two hydraulic cylinders, which represent the caliper pistons, equipped with a hard stop which models pad–disc clearance.

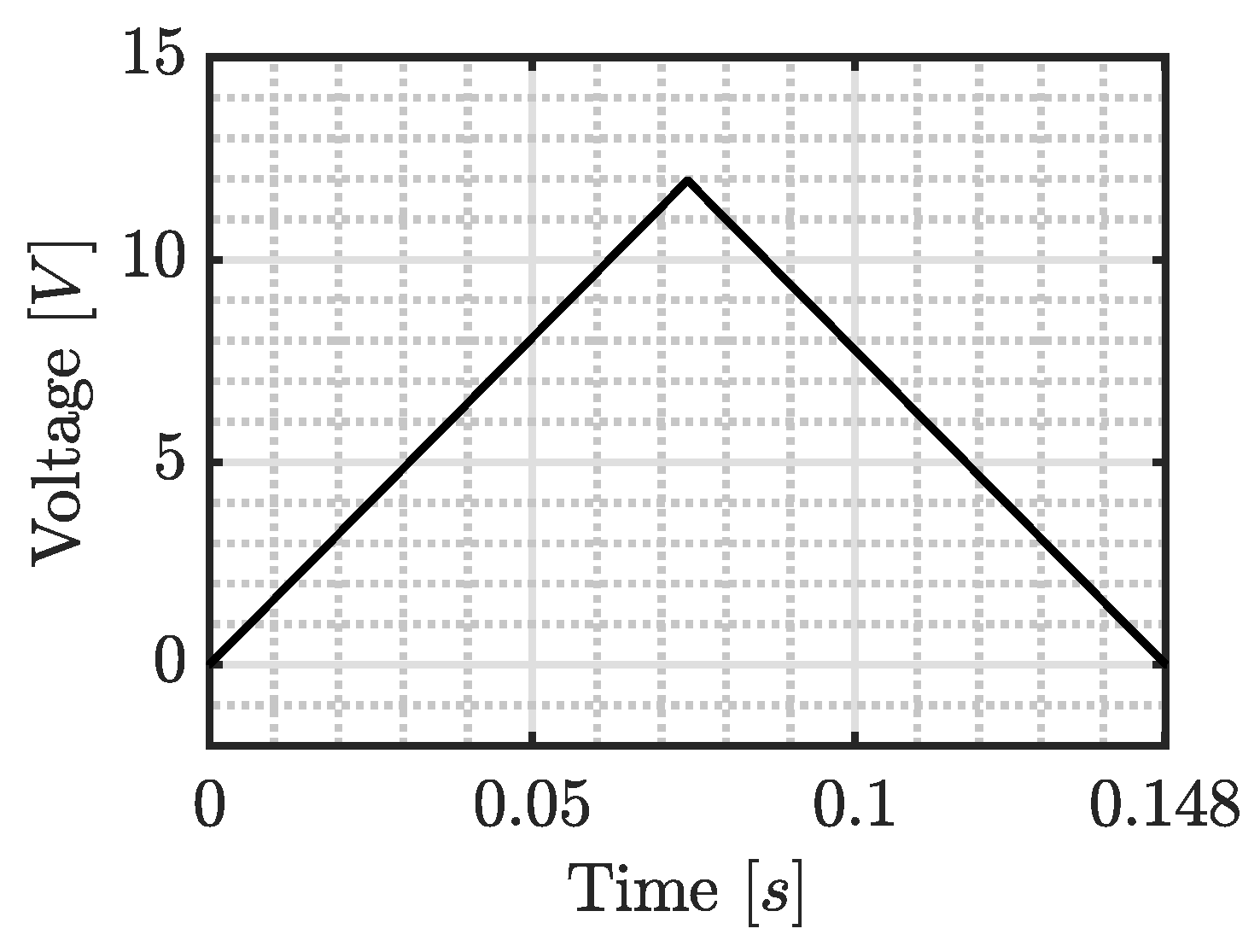

Figure 6 shows the voltage time history that drives the system to close the pad–disc gap in

and to reach

bar, as computed in step (4) of the optimization framework. Notice that the reference voltage of the motor drive—which can be produced through appropriate PWM—has a triangular shape. This ensures a null final velocity, thus reducing the overshoot caused by the pad–disc clearance being filled. By feeding such voltage time history into the DC motor in the multiphysics model, the coherence between the two presented models can be assessed.

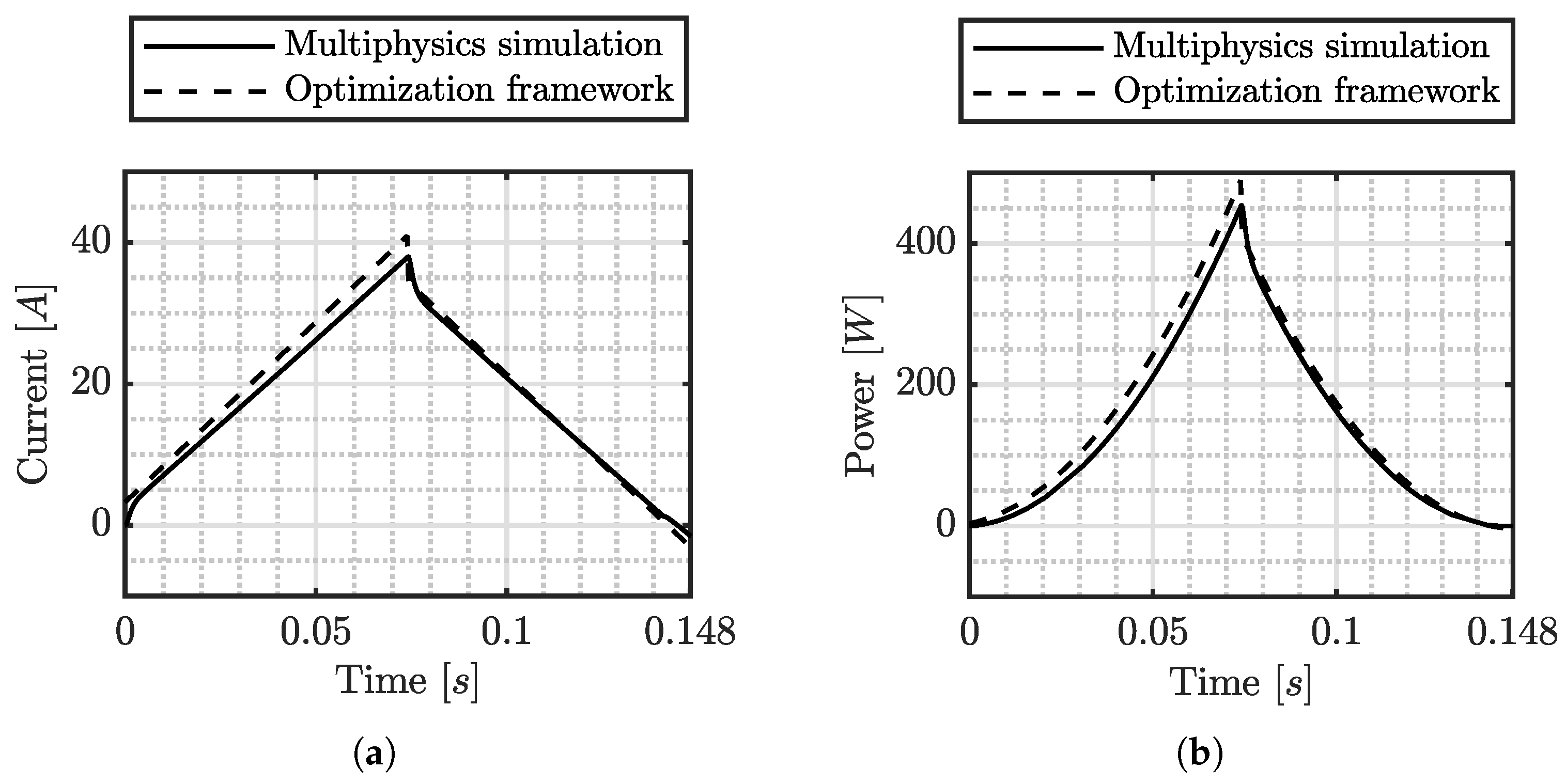

Figure 7a shows the behavior of the current during Phase A for the multiphysics model and optimization framework. The maximum current is 38

for the former, and

for the latter, leading to a percentage error of 7.6%. Steady-state conditions are not shown in the figure for the sake of clarity, but the steady-state current resulted in

during Phase B, showing perfect agreement with the optimization framework (

Table 2b). The same holds for

Figure 7b with the multiphysics model showing a maximum power of 454 W, i.e., the optimization framework overestimates by 7.7%. The comparison between the multiphysics model and the optimization framework indicates a satisfactory level of consistency between the two models, supporting the use of the proposed methodology for preliminary design and assessment of performance metrics.

4.2. Dynamic Behavior

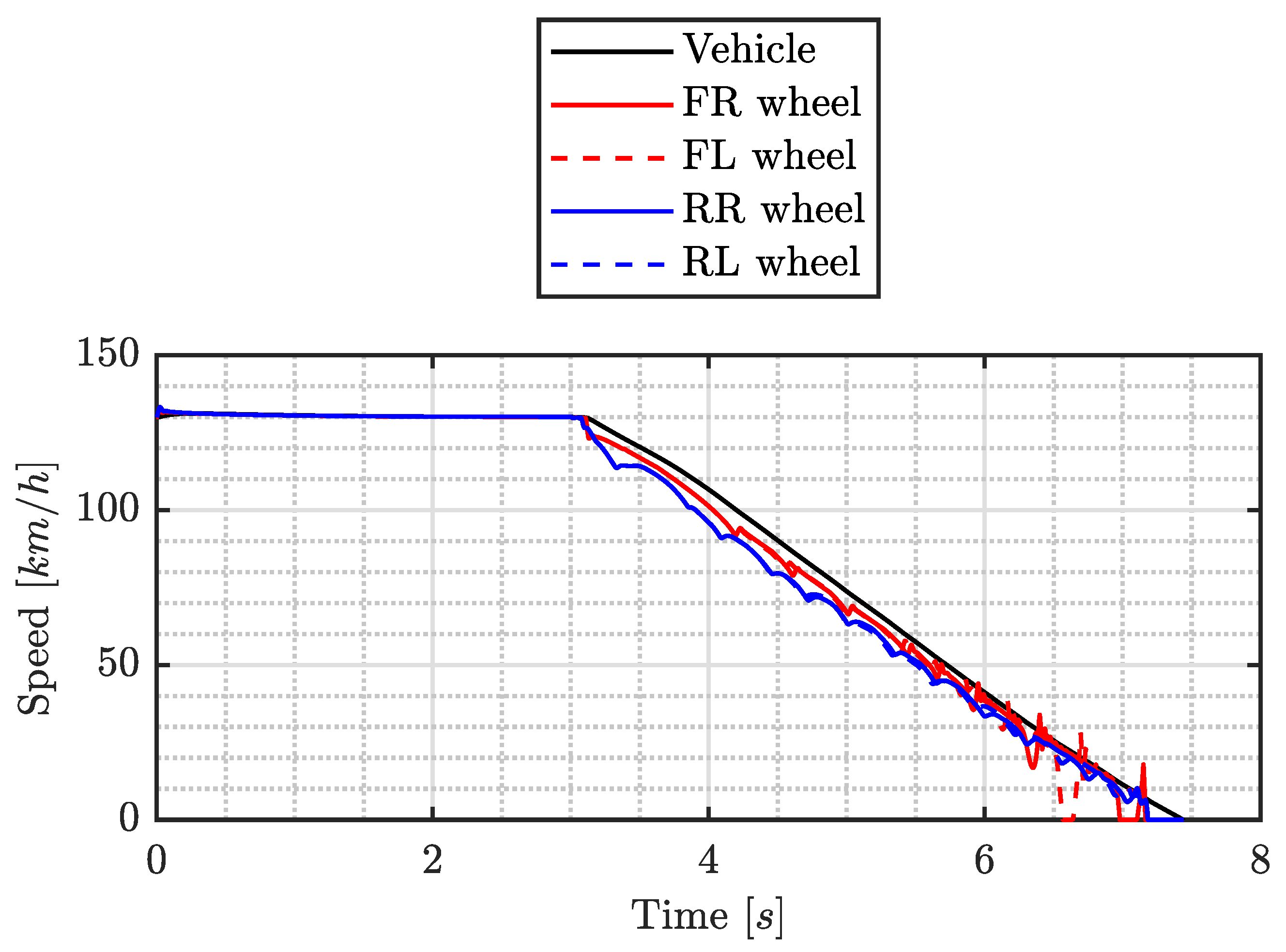

The dynamic behavior of the system when coupled with a high-level vehicle dynamics control logic was also studied. The vehicle is modeled as a 14 DoFs system, the low-level control logic for the braking pressure at each corner is constituted by a PID controller on the master cylinder position and a PID controller on the master cylinder pressure. The reference pressure to the latter controller is provided by a high-level ECU integrating longitudinal dynamics control through an acceleration threshold-based controller (henceforth, ABS), which prevents wheel locking. An emergency braking maneuver is performed from an initial speed of 130

/

. The time histories for the speed of vehicle and wheels are reported in

Figure 8, from which it is visible that wheel locking is avoided above the threshold for ABS deactivation.

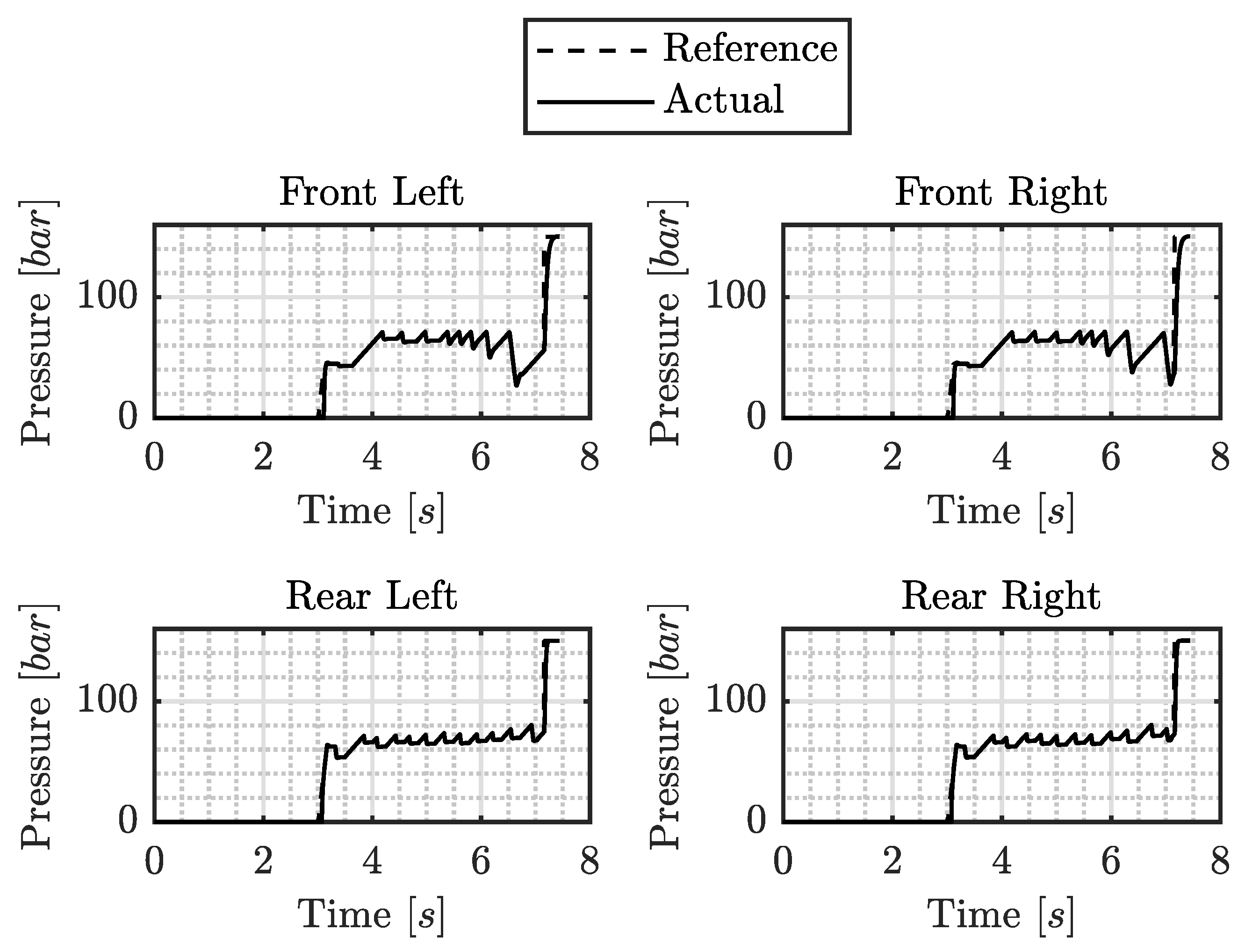

Figure 9 shows that the DEHB system accurately tracks pressure demand from the ECU.

The main performance indicators retrieved from the longitudinal maneuver are the mean fully developed deceleration MFDD = and the stopping distance SD = . With respect to the vehicle without longitudinal dynamics control, MFDD shows an increase of 31.5% and a stopping distance reduction of 15.7%. This indicates the good performance of the DEHB when coupled with vehicle dynamics control logic.

4.3. Comparison with a Non-Optimized Solution

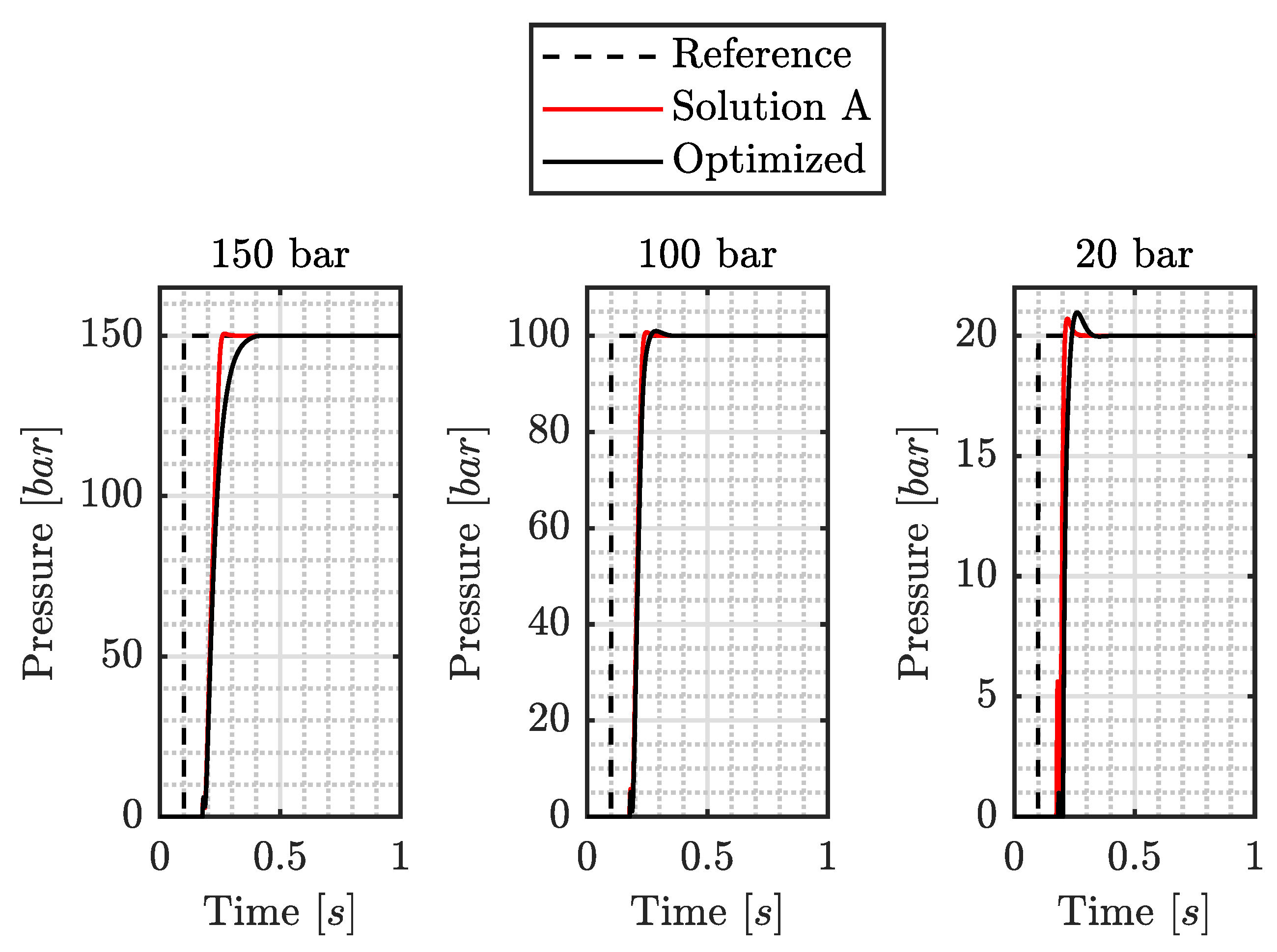

As a last step, in order to evaluate the results of the optimization, a comparison in terms of electrical performance between the two DEHB systems reported in

Table 4 is provided. Solution A refers to a non-optimized solution, which is driven by a commercial motor (Motor A in

Table 3).

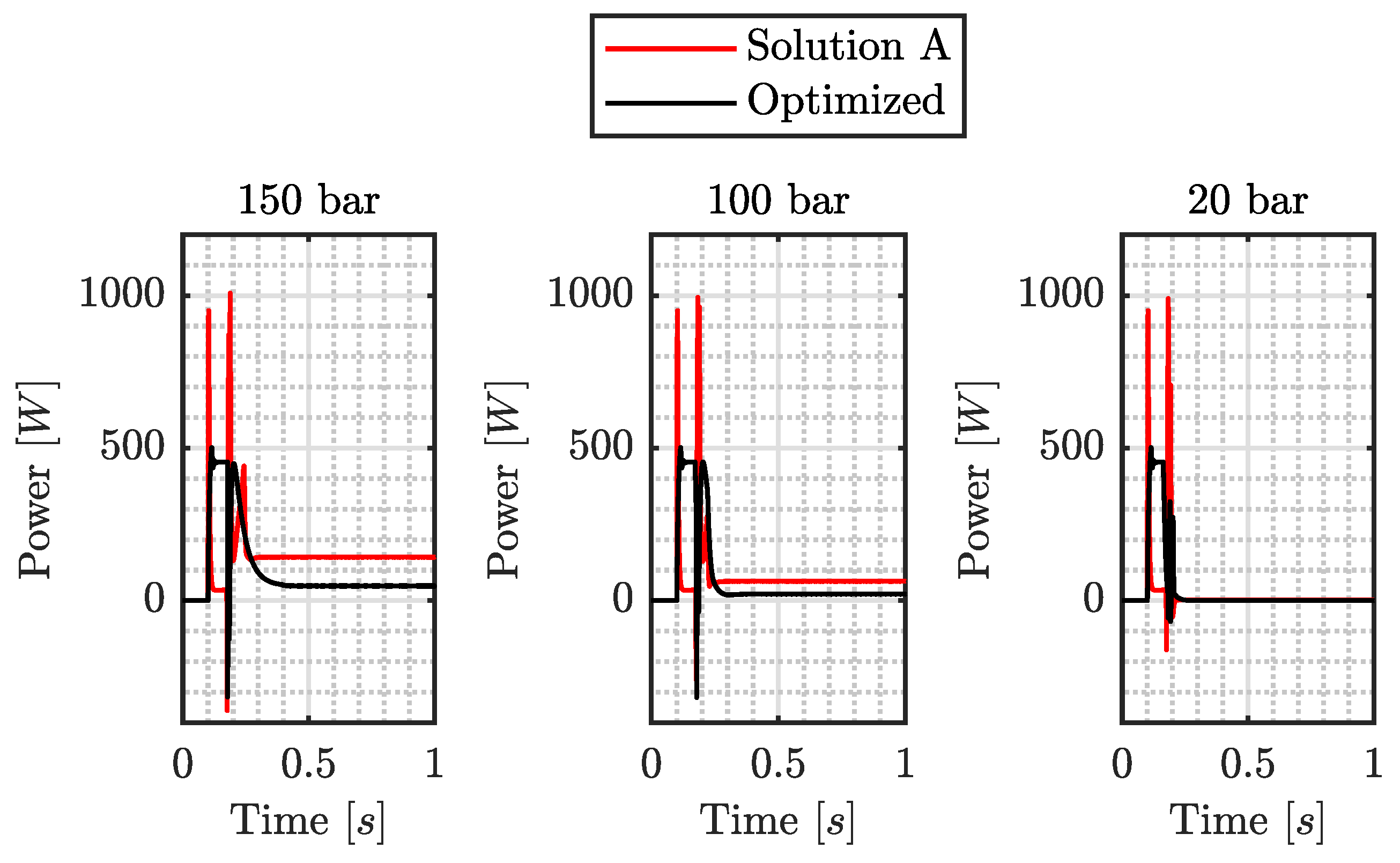

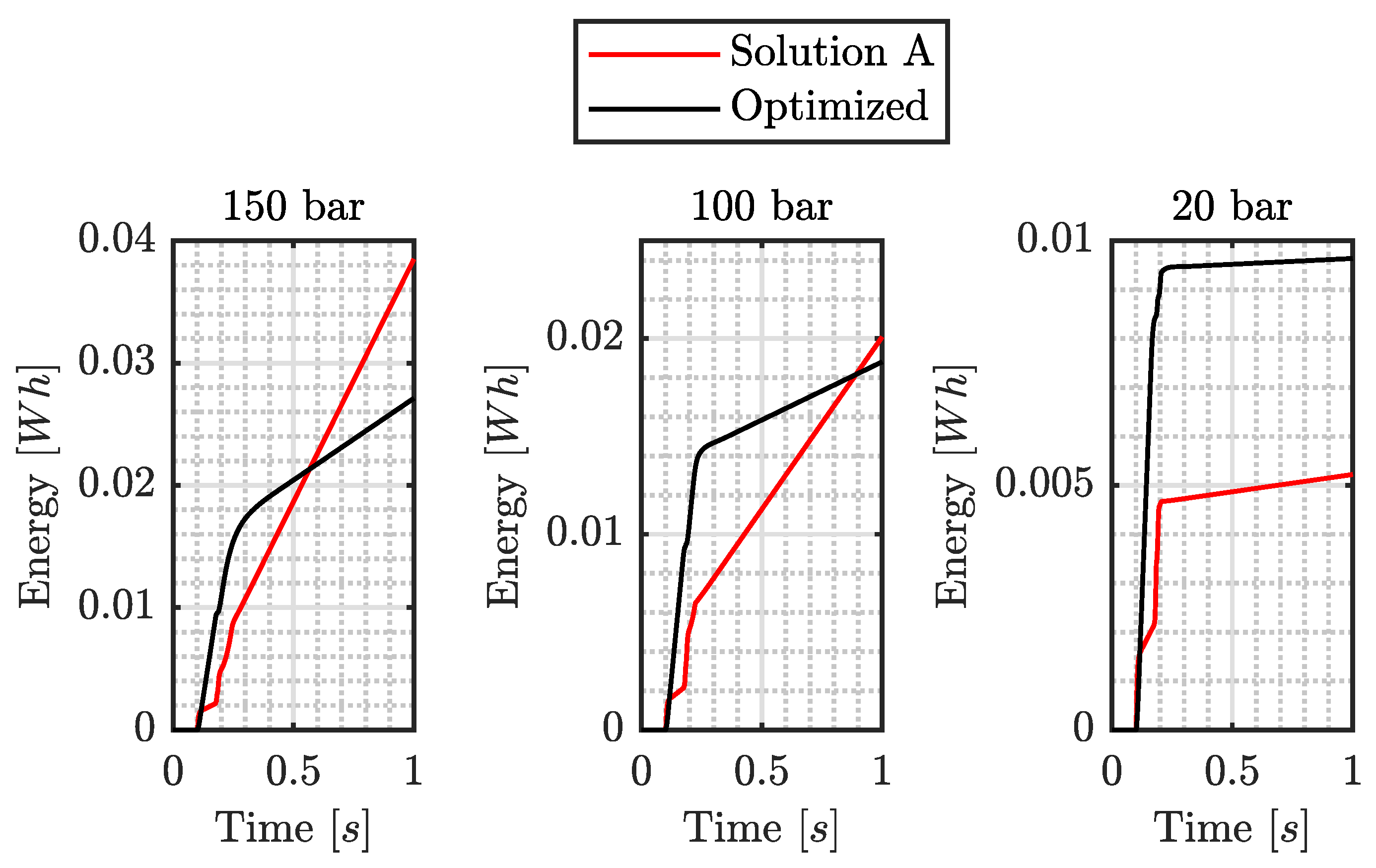

The comparison is carried out in terms of pressure steps at different pressure levels, which are reported in

Figure 10. The dynamics of the two solutions are comparable at 100 bar and 20 bar, while the optimized solution is slower at 150 bar, this being the maximum pressure considered during the design phase. From the plots of current and power (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12), the benefits of the optimization are visible, resulting in halved values. Finally,

Figure 13 reports electrical energy consumption: the optimized solution requires more energy during Phase A, but the required energy for the holding pressure is significantly reduced. This confirms that the design optimization significantly reduces power consumption, especially during long braking events.

A comparison between the two solutions during an emergency braking event shows a total energy consumption for the four corners that is halved for the optimized solution, highlighting once again the necessity of design optimization to increase the overall efficiency of the DEHB system.

5. Conclusions

The paper focuses on the development of an optimization framework for the optimal design of the mechanical and electrical parameters of a distributed electro-hydraulic brake. The framework is able to leverage the mathematical model of the system to compute all the relevant outputs for the optimization problem, with an error below 8% if compared to a multiphysics model. The sensitivity analysis highlights the most influencing variables, which are optimized through a genetic algorithm. The optimized system, when coupled with high-level vehicle dynamics control strategies, shows good dynamic performance during braking maneuvers. In particular, the introduction of an ABS logic allows for an increase of 31.5% in MFDD and a decrease of 15.7% in stopping distance. A comparison of the optimized solution with a non-optimized one makes it possible to highlight the benefits of the procedure, which reduces the required power by up to 50%.

The presented approach to the preliminary optimal sizing of distributed braking systems has produced encouraging results, outlining a methodology that can be further extended to enhance the modeling process—especially on the electrical side—by accounting for BLDC motors, which are commonly employed in these types of applications. Experimental validation of the proposed framework on a prototype would increase the scientific relevance of the work, making it possible to quantify the model–experiment agreement and to evaluate the robustness and performance of the optimized design in real-world braking scenarios where nonlinear behavior due to friction and pad thermal fade is not negligible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and M.V.; methodology, M.B.; software, M.B.; validation, G.G., M.G. and M.V.; formal analysis, G.G.; investigation, G.G. and M.G.; resources, M.V.; data curation, G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.; writing—review and editing, M.V. and G.G.; visualization, G.G.; supervision, M.V. and L.S.; project administration, M.V. and L.S.; funding acquisition, F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Volvo Cars Corporation.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not readily available due to confidentiality agreements and proprietary restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out in collaboration with Volvo Cars Corporation, whose support, technical expertise, and commitment to innovation greatly contributed to the success of this research. The authors are grateful for the opportunity to work closely with the company throughout the entire project.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Lorenzo Savi was employed by the company Volvo Car Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| Rotation |

| Rotational inertia |

| Damping |

| Torque |

| Armature resistance |

| Armature inductance |

| Armature voltage |

| I | Armature current |

| Torque constant |

| Rotor diameter |

| | Rotor length |

| Rotor density |

| Copper density |

| Winding wire diameter |

| Number of windings |

| Permanent magnet flux |

| Transmission ratio |

| Efficiency |

| Lead |

| Transmission ratio |

| Rotational inertia |

| Damping |

| Direct motion efficiency |

| Reverse motion efficiency |

| Axial force |

| Displacement |

| Piston mass |

| Oil scraper damping |

| Oil scraper stiffness |

| Piston surface |

| p | Hydraulic fluid pressure |

| Piston displacement |

| Piston mass |

| Oil scraper damping |

| Oil scraper stiffness |

| Pad stiffness |

| Number of caliper pistons |

| Piston surface |

| Caliper volume |

| Generalized mass at the master cylinder |

| Generalized inertia at the motor |

| Generalized damping |

| Generalized stiffness |

| Hydraulic fluid bulk modulus |

| Time to fill pad–disc clearance |

References

- Sanguesa, J.A.; Torres-Sanz, V.; Garrido, P.; Martinez, F.J.; Marquez-Barja, J.M. A review on electric vehicles: Technologies and challenges. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 372–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.P.; Li, S.H. Brake-by-wire system for passenger cars: A review of structure, control, key technologies, and application in X-by-wire chassis. eTransportation 2023, 18, 100–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savi, L.; Garosio, D.; Floros, D.; Travagliati, A.; Vignati, M.; Braghin, F. Benchmark of Conventional and by-Wire Brake System Layouts for Electric Vehicle Applications by Numerical Simulations; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanami, N.; Nikzadfar, K. A novel hierarchical controller for efficient and safe blending of hydraulic and regenerative braking systems in electric vehicles. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2025, 13, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignati, M.; Belloni, M.; Sabbioni, E.; Tarsitano, D. A Regenerative Braking Strategy for Independently Driven Electric Wheel Accounting for Contemporary Use of Electric and Hydraulic Brakes. In Proceedings of the Advances in Dynamics of Vehicles on Roads and Tracks II; Orlova, A., Cole, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1256–1268. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Zhuang, W.; Wei, W.; Yin, G. A State-of-the-Art Review on the Revolution of Structure and Control of Vehicle Chassis System: From Tradition to Distributed Chassis System. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2025, 38, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignati, M.; Belloni, M.; Tarsitano, D.; Sabbioni, E. Optimal Cooperative Brake Distribution Strategy for IWM Vehicle Accounting for Electric and Friction Braking Torques. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 1088805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, M.; Bracaccia, L.; Vignati, M.; Tarsitano, D. Thermomechanical Model Predictive Cascade Control for Blended Braking of an IWM Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference (VPPC), Milan, Italy, 24–27 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ping, X.; Shi, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, X. Energy recovery strategy for regenerative braking system of intelligent four-wheel independent drive electric vehicles. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 15, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumiel, J.Á.; Mabe, J.; Burguera, F.; Jiménez, J.; Barruetabeña, J. Next-Generation Pedal: Integration of Sensors in a Braking Pedal for a Full Brake-by-Wire System. Sensors 2023, 23, 6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydrich, M.; Ricciardi, V.; Ivanov, V.; Mazzoni, M.; Rossi, A.; Buh, J.; Augsburg, K. Integrated Braking Control for Electric Vehicles with In-Wheel Propulsion and Fully Decoupled Brake-by-Wire System. Vehicles 2021, 3, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, C.; Tong, Q. Optimal Torque Distribution Strategy for Electric Vehicles with Electro-Hydraulic Compound Braking System. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th CAA International Conference on Vehicular Control and Intelligence (CVCI), Changsha, China, 27–29 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xiong, L.; Zhuo, G.; Tian, W.; Li, J.; Shu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Xu, G. A Review of One-Box Electro-Hydraulic Braking System: Architecture, Control, and Application. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xiong, L.; Zhuo, G.; Shu, Q.; Zhao, X. Electro-Hydraulic Composite Braking Control Optimization for Front-Wheel-Driven Electric Vehicles Equipped with Integrated Electro-Hydraulic Braking System; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Di, Y.; Miao, X. Single-wheel failure stability control for vehicle equipped with brake-by-wire system. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydrich, M.; Lenz, M.; Ivanov, V.; Stoev, J.; Lecoutere, J. Concept of an Electromechanical Brake-By-Wire System for Battery-Electric Vehicles; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; Ge, W.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gongye, X. Review on the Development, Control Method and Application Prospect of Brake-by-Wire Actuator. Actuators 2020, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, L.; Wang, Y.; You, C.; Ma, L.; Song, J. Prototype of Distributed Electro-Hydraulic Braking System and Its Fail-Safe Control Strategy; SAE Technical Paper 2013-01-2066; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, R.; Todeschini, F.; Araújo, R.; Corno, M.; Freitas, D. Adaptive-Robust Friction Compensation in a Hybrid Brake-by-Wire Actuator. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part I J. Syst. Control Eng. 2013, 228, 769–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, C.; Manzie, C.; Good, M.C. Electromechanical Brake Modeling and Control: From PI to MPC. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2008, 16, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Sun, H.; Wang, N.; Niu, Z.; Wan, R. Sliding Mode Control of Hydraulic Pressure in Electro-Hydraulic Brake System Based on the Linearization of Higher-Order Model. Fluid Dyn. Mater. Process. 2020, 16, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, S. Variable boost characteristic control strategy of hydraulic systems for brake-by-wire based on driving style. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ding, R.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, R.; Zhao, B.; Liao, Y. Research on coordinated control of electro-hydraulic composite braking for an electric vehicle based on the Fuzzy-TD3 deep reinforcement learning algorithm. Control Eng. Pract. 2025, 157, 106248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yang, F. A design method for booster motor of brake-by-wire system based on intelligent electric vehicle. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2023, 2, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasteh, E.; Assadian, F. A Comparative Analysis of Brake-by-Wire Smart Actuators Using Optimization Strategies. Energies 2022, 15, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Kim, J.; Cheon, J.S.; Moon, H.i.; Chae, H.J. Multi-objective optimization and robust design of brake by wire system components. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars-Mech. Syst. 2013, 6, 1465–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Chen, X.; Yan, M.; Hang, P. Design and Optimization of a Novel Electronic Mechanical Brake Actuator Based on Cam. Actuators 2023, 12, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velumani, S.; Balasubramani, A. Optimization of Brake System Parameters Using Genetic Algorithm; SAE Technical Paper 2023-01-1881; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Li, J.; Qin, X. Braking performance oriented multi–objective optimal design of electro–mechanical brake parameters. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e02517141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

DEHB system layout: 1. electric motor; 2. gearbox; 3. ball screw; 4. master cylinder; 5. hydraulic pipeline; 6. brake fluid reservoir; 7. brake caliper; 8. brake pistons; and 9. brake disc.

Figure 1.

DEHB system layout: 1. electric motor; 2. gearbox; 3. ball screw; 4. master cylinder; 5. hydraulic pipeline; 6. brake fluid reservoir; 7. brake caliper; 8. brake pistons; and 9. brake disc.

Figure 2.

Lumped parameter model of the DEHB braking system. (a) Physical scheme of the model. (b) Representation of forces.

Figure 2.

Lumped parameter model of the DEHB braking system. (a) Physical scheme of the model. (b) Representation of forces.

Figure 3.

Influence of master cylinder diameter on (a) time to contact; (b) maximum torque required by the motor; (c) maximum motor current; and (d) electric power absorbed by the motor.

Figure 3.

Influence of master cylinder diameter on (a) time to contact; (b) maximum torque required by the motor; (c) maximum motor current; and (d) electric power absorbed by the motor.

Figure 4.

Influence of ball screw lead on (a) time to contact; (b) maximum torque required by the motor; (c) maximum motor current; and (d) electric power absorbed by the motor.

Figure 4.

Influence of ball screw lead on (a) time to contact; (b) maximum torque required by the motor; (c) maximum motor current; and (d) electric power absorbed by the motor.

Figure 5.

Influence of rotor diameter on (a) time to contact; (b) maximum torque required by the motor; (c) maximum motor current; and (d) electric power absorbed by the motor.

Figure 5.

Influence of rotor diameter on (a) time to contact; (b) maximum torque required by the motor; (c) maximum motor current; and (d) electric power absorbed by the motor.

Figure 6.

Reference voltage to the DC motor, as computed by the optimization framework, for a gap-closure transient of and a steady-state pressure of 150 bar.

Figure 6.

Reference voltage to the DC motor, as computed by the optimization framework, for a gap-closure transient of and a steady-state pressure of 150 bar.

Figure 7.

Comparison between the outputs of the multiphysics model (solid line) and of the optimization framework (dashed line) when the DC motor is supplied with the voltage time history computed by the latter, starting from the rest condition. (a) Current. (b) Power.

Figure 7.

Comparison between the outputs of the multiphysics model (solid line) and of the optimization framework (dashed line) when the DC motor is supplied with the voltage time history computed by the latter, starting from the rest condition. (a) Current. (b) Power.

Figure 8.

Velocity time history during ABS emergency braking maneuver for: vehicle (black line), front right wheel (red solid line), front left wheel (red dashed line), rear right wheel (blue solid line), and rear left wheel (blue dashed line).

Figure 8.

Velocity time history during ABS emergency braking maneuver for: vehicle (black line), front right wheel (red solid line), front left wheel (red dashed line), rear right wheel (blue solid line), and rear left wheel (blue dashed line).

Figure 9.

Braking pressure time history during ABS emergency braking for each corner: ECU reference (dashed line) and actual pressure (solid line).

Figure 9.

Braking pressure time history during ABS emergency braking for each corner: ECU reference (dashed line) and actual pressure (solid line).

Figure 10.

Comparison of two DEHB solutions—optimized (black line) and Solution A (red line)—when simulating an emergency braking maneuver on a high-friction road (pressure time history).

Figure 10.

Comparison of two DEHB solutions—optimized (black line) and Solution A (red line)—when simulating an emergency braking maneuver on a high-friction road (pressure time history).

Figure 11.

Comparison of two DEHB solutions—optimized (black line) and Solution A (red line)—when simulating an emergency braking maneuver on a high-friction road (current time history).

Figure 11.

Comparison of two DEHB solutions—optimized (black line) and Solution A (red line)—when simulating an emergency braking maneuver on a high-friction road (current time history).

Figure 12.

Comparison of two DEHB solutions—optimized (black line) and Solution A (red line)—when simulating an emergency braking maneuver on a high-friction road (power time history).

Figure 12.

Comparison of two DEHB solutions—optimized (black line) and Solution A (red line)—when simulating an emergency braking maneuver on a high-friction road (power time history).

Figure 13.

Comparison of two DEHB solutions—optimized (black line) and Solution A (red line)—when simulating an emergency braking maneuver on a high-friction road (energy time history).

Figure 13.

Comparison of two DEHB solutions—optimized (black line) and Solution A (red line)—when simulating an emergency braking maneuver on a high-friction road (energy time history).

Table 1.

List of the design variables and their respective bounds considered in the optimization of the DEHB system.

Table 1.

List of the design variables and their respective bounds considered in the optimization of the DEHB system.

| DV | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|

| | |

| | |

| | |

| | |

| | |

| 50 | 1000 |

Table 2.

Results of the optimization procedure.

Table 2.

Results of the optimization procedure.

| (a) DVs. | |

| DV | Optimal Value |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| 71 |

| (b) Outputs. | |

| Output | Optimal Value |

| |

| |

| 489 |

| |

| |

| 12 |

| |

| |

| |

Table 3.

Comparison, in terms of structural parameters, of the optimized motor with commercial motors.

Table 3.

Comparison, in terms of structural parameters, of the optimized motor with commercial motors.

| Parameter | Optimized | Motor A | Motor B | Motor C | Motor D | Motor E |

|---|

| [] | 0.0277 | 0.36 | 0.214 | 0.115 | 0.103 | 0.0821 |

| [/] | 0.0105 | 0.04243 | 0.067 | 0.0164 | 0.0385 | 0.0537 |

| [] | | | | | | |

| [] | 27 | 38 | 80 | 40 | 50 | 65 |

| [] | 45 | 90 | 175 | 71 | 108 | 131 |

Table 4.

Comparison of structural parameters of the optimized DEHB and a non-optimized DEHB (Solution A).

Table 4.

Comparison of structural parameters of the optimized DEHB and a non-optimized DEHB (Solution A).

| Parameter | Optimized | Solution A |

|---|

| | 20 |

| | 6 |

| | |

| [] | 0.0277 | 0.36 |

| [/] | 0.0105 | 0.04243 |

| [] | | |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |