Emerging Insights into the Molecular Basis of Osteoarthritis Pathogenesis and Treatment Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Osteoarthritis at the Synovial-Joint Scale

2.1. The Articular Cartilage in Osteoarthritis

2.2. The Synovial Cavity in Osteoarthritis

2.3. Subchondral Bone in Osteoarthritis

2.4. Bone Marrow in Osteoarthritis

3. Prominent Cell Types Associated with Osteoarthritis

3.1. Articular Chondrocytes in Osteoarthritis

3.2. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Osteoarthritis

3.3. Immune Cells Regulate Inflammation in Osteoarthritis with Inflammatory Cytokines

4. Molecular Pathways

4.1. WNT Signaling in Osteoarthritis

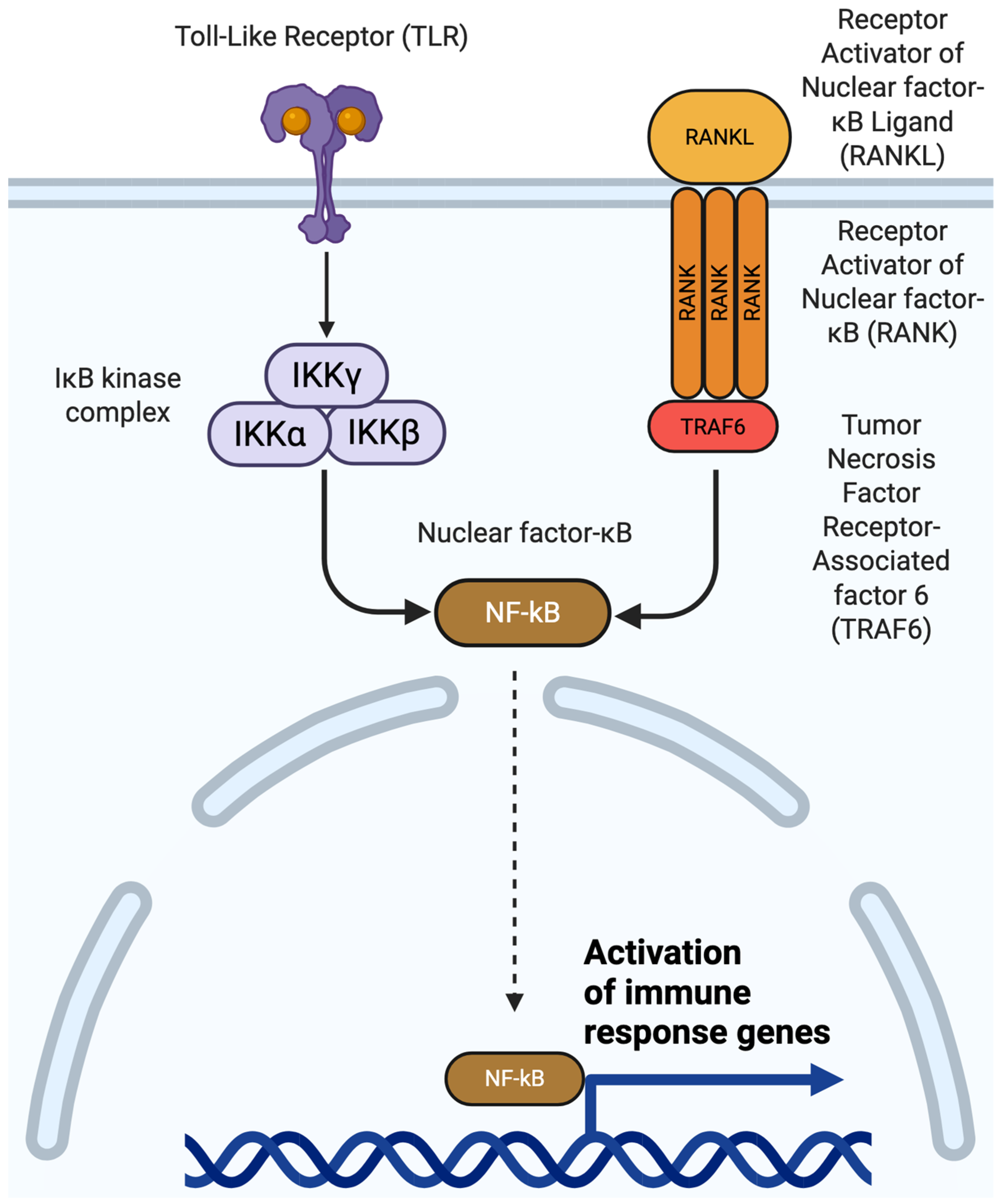

4.2. NF-κB Signaling in Osteoarthritis

4.3. RANK/RANKL Signaling in Osteoarthritis

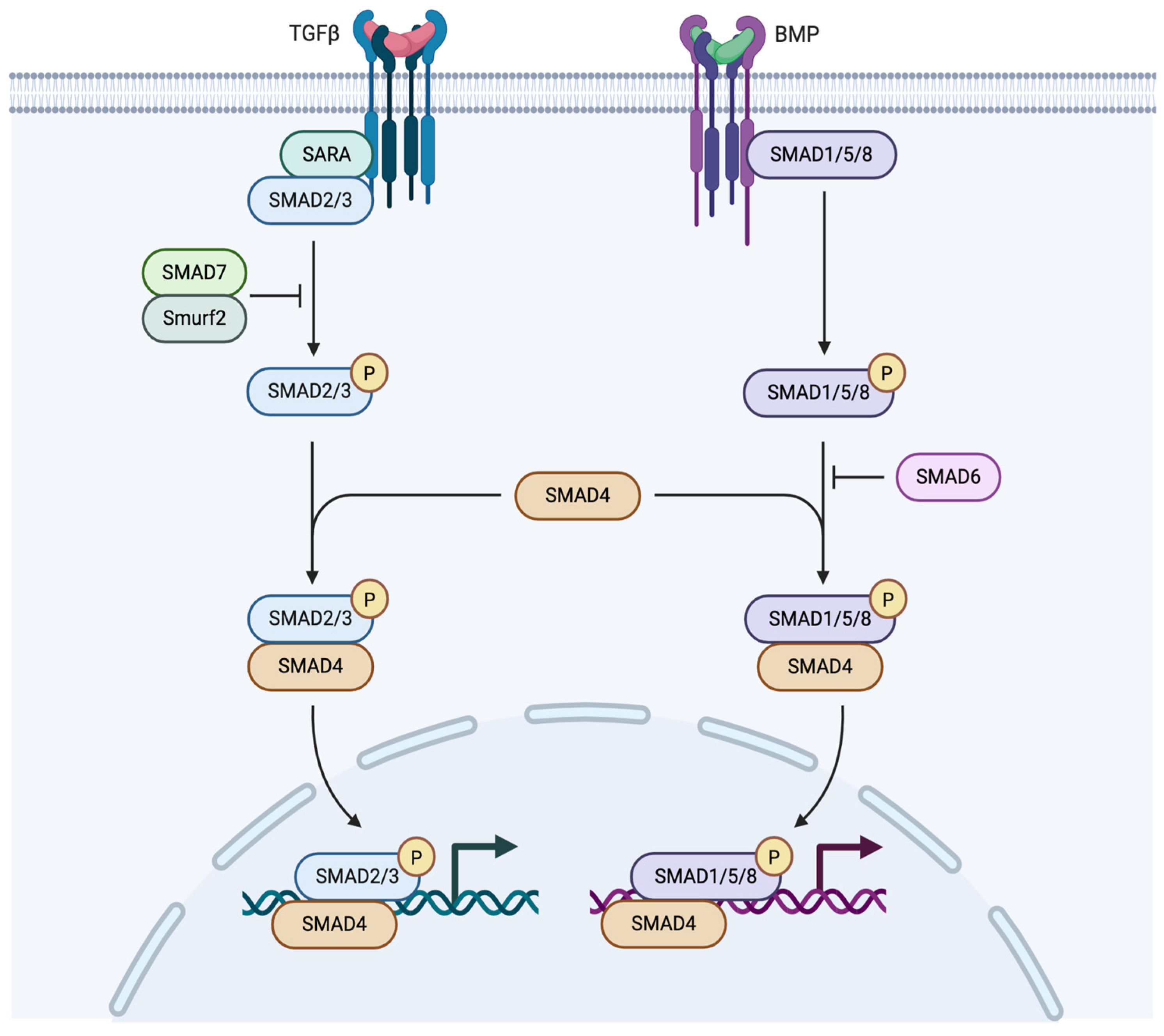

4.4. TGF-β Signaling in Osteoarthritis

4.5. Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signaling in Osteoarthritis

5. Major Transcription Factors Associated with Osteoarthritis

Transcription Factor Key Interactions in Osteoarthritis

- SOX9 interacting with: WNT, RUNX2, TGF, SMADS (from Smads), NF-κB.

- RELA/NF-κB: Self, SOX9, HIF-2α, AP1.

- AP1 interacting with: NF-κB, RUNX2, SOX9, MAPK.

6. Treatments for Osteoarthritis

6.1. Emerging Osteoarthritis Treatments

6.1.1. MSC Injection

6.1.2. Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation

6.1.3. Platelet-Rich Plasma

6.1.4. Pulsed Electromagnetic Field

6.1.5. Sprifermin

6.1.6. CK2.1

6.2. Additional Emerging Osteoarthritis Treatments

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2021 Osteoarthritis Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990–2020 and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e508–e522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, N.A.; Nilges, J.M.; Oo, W.M. Sex differences in osteoarthritis prevalence, pain perception, physical function and therapeutics. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2024, 32, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Jordan, J.M. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2010, 26, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucesoy, B.; Charles, L.E.; Baker, B.; Burchfiel, C.M. Occupational and genetic risk factors for osteoarthritis: A review. Work 2015, 50, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Moreno, M.; Rego, I.; Carreira-Garcia, V.; Blanco, F.J. Genetics in Osteoarthritis. Curr. Genom. 2008, 9, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhishek, A.; Doherty, M. Diagnosis and clinical presentation of osteoarthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 39, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaccioli, S.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Zis, P.; Rinonapoli, G.; Varrassi, G. Osteoarthritis: New Insight on Its Pathophysiology. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Yuan, Q.; Wan, X.; Yang, M.; Xu, P. Effect of immune cells on different cells in OA. JIR J. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 16, 2329–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasioli, D.J.; Kaplan, D.L. The roles of catabolic factors in the development of osteoarthritis. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2014, 20, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.H.; Jeon, S.; Park, J.; Ryu, J.H.; Mobasheri, A.; Matta, C.; Jin, E.-J. Progressing future osteoarthritis treatment toward precision medicine: Integrating regenerative medicine, gene therapy and circadian biology. Exp. Mol. Med. 2025, 57, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigkilidas, D.; Anand, A. The effectiveness of hyaluronic acid intra-articular injections in managing osteoarthritic knee pain. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2013, 95, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Felthaus, O.; Prantl, L. Adipose Tissue-Derived Therapies for Osteoarthritis: Multifaceted Mechanisms and Clinical Prospects. Cells 2025, 14, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigley, C.; Trivedi, J.; Meghani, O.; Owens, B.D.; Jayasuriya, C.T.; Shigley, C.; Trivedi, J.; Meghani, O.; Owens, B.D.; Jayasuriya, C.T. Suppressing Chondrocyte Hypertrophy to Build Better Cartilage. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tan, X.-N.; Hu, S.; Liu, R.-Q.; Peng, L.-H.; Li, Y.-M.; Wu, P. Molecular Mechanisms of Chondrocyte Proliferation and Differentiation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 664168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A.J.S.; Bedi, A.; Rodeo, S.A. The Basic Science of Articular Cartilage: Structure, Composition, and Function. Sports Health 2009, 1, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuasa, T.; Otani, T.; Koike, T.; Iwamoto, M.; Enomoto-Iwamoto, M.; Yuasa, T.; Otani, T.; Koike, T.; Iwamoto, M.; Enomoto-Iwamoto, M. Wnt/β-catenin signaling stimulates matrix catabolic genes and activity in articular chondrocytes: Its possible role in joint degeneration. Lab. Investig. 2008, 88, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.P.; Wei, X.C.; Li, P.C.; Chen, C.W.; Wang, X.H.; Jiao, Q.; Wang, D.M.; Wei, F.Y.; Zhang, J.Z.; Wei, L. The Role of miRNAs in Cartilage Homeostasis. Curr. Genom. 2015, 16, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, P.K.; Lambrou, G.I. The Involvement of MicroRNAs in Osteoarthritis and Recent Developments: A Narrative Review. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 2018, 29, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, C.A. Articular cartilage chondrons: Form, function and failure. J. Anat. 1997, 191, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Merchán, E.C.; Rodríguez-Merchán, E.C. Molecular Mechanisms of Cartilage Repair and Their Possible Clinical Uses: A Review of Recent Developments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallich, A.A.; Rath, E.; Atzmon, R.; Radparvar, J.R.; Fontana, A.; Sharfman, Z.; Amar, E. Chondral lesions in the hip: A review of relevant anatomy, imaging and treatment modalities. J. Hip Preserv. Surg. 2019, 6, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yin, H.; Yan, Z.; Li, H.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wei, F.; Tian, G.; Ning, C.; Li, H.; et al. The immune microenvironment in cartilage injury and repair. Acta Biomater. 2022, 140, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.-K.; Su, Y.-Z.; Wang, X.-X.; Bai, B.; Zhang, C.-Q.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Zhang, G.-L. Synovial Macrophages: Past Life, Current Situation, and Application in Inflammatory Arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 905356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lopez, E.; Coras, R.; Torres, A.; Lane, N.E.; Guma, M.; Sanchez-Lopez, E.; Coras, R.; Torres, A.; Lane, N.E.; Guma, M. Synovial inflammation in osteoarthritis progression. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2022, 18, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigoglou, S.; Papavassiliou, A.G. The NF-κB signalling pathway in osteoarthritis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 45, 2580–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Jing, Y.; Su, J.; Hu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Jing, Y.; Su, J. Subchondral bone microenvironment in osteoarthritis and pain. Bone Res. 2021, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Chen, Y.; Dou, C.; Dong, S. Microenvironment in subchondral bone: Predominant regulator for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-M.; Lin, C.; Stavre, Z.; Greenblatt, M.B.; Shim, J.-H. Osteoblast-Osteoclast Communication and Bone Homeostasis. Cells 2020, 9, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Huang, B.; Jing, Y.; Su, J. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: Identification, Classification, and Differentiation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 9, 787118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Mai, Y.; Fang, X.; Wang, Z.; Xue, S.; Chen, H.; Dang, Q.; Wang, X.; Tang, S.A.; Ding, C.; et al. Bone marrow lesions in osteoarthritis: From basic science to clinical implications. Bone Rep. 2023, 18, 101667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, J.; Bates, D.; Boyd, R.; Shah, K.; Barnard, A.; Huguenin, L.; Tenen, A.; Freitag, J.; Bates, D.; Boyd, R.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in the treatment of osteoarthritis: Reparative pathways, safety and efficacy—A review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2016, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkiraju, H.; Nohe, A. Role of Chondrocytes in Cartilage Formation, Progression of Osteoarthritis and Cartilage Regeneration. J. Dev. Biol. 2015, 3, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielty, C.M.; Kwan, A.P.L.; Holmes, D.F.; Schor, S.L.; Grant, M.E. Type X collagen, a product of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Biochem. J. 1985, 227, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Wu, R.W.H.; Lam, Y.; Chan, W.C.W.; Chan, D. Hypertrophic chondrocytes at the junction of musculoskeletal structures. Bone Rep. 2023, 19, 101698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaswal, A.P.; Kumar, B.; Roelofs, A.J.; Iqbal, S.F.; Singh, A.K.; Riemen, A.H.K.; Wang, H.; Ashraf, S.; Nanasaheb, S.V.; Agnihotri, N.; et al. BMP signaling: A significant player and therapeutic target for osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2023, 31, 1454–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, B.Y.; Little, C.B.; Chan, B.Y.; Little, C.B. The interaction of canonical bone morphogenetic protein- and Wnt-signaling pathways may play an important role in regulating cartilage degradation in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jin, C.; Hua, J.; Chen, Z.; Gao, W.; Xu, W.; Zhou, L.; Shan, L. Roles of microenvironment on mesenchymal stem cells therapy for osteoa. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 7069–7079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, V.; Matišić, V.; Kodvanj, I.; Bjelica, R.; Jeleč, Ž.; Hudetz, D.; Rod, E.; Čukelj, F.; Vrdoljak, T.; Vidović, D.; et al. Cytokines and Chemokines Involved in Osteoarthritis Pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, A.; Jung, S.H.; Pyo, S.; Kim, S.Y.; Jo, S.; Kim, L.; Lee, E.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, S.-R. 3′-Sialyllactose Protects SW1353 Chondrocytic Cells from Interleukin-1β-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 609817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, M.; Ma, Y.; Li, R.; Jin, X.; Gao, L.; Wang, Z. Changes of type II collagenase biomarkers on IL-1β-induced rat articular chondrocytes. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, F.; Fan, C.; Wang, C.; Ruan, H. Analysis of isoform specific ERK signaling on the effects of interleukin-1β on COX-2 expression and PGE2 production in human chondrocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 402, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Bau, B.; Yang, H.; Soeder, S.; Aigner, T. Freshly isolated osteoarthritic chondrocytes are catabolically more active than normal chondrocytes, but less responsive to catabolic stimulation with interleukin-1β. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Li, M.; Bai, R. The Wnt signaling cascade in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis and related promising treatment strategies. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 954454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietman, C.; Wu, B.; Lechner, S.; Shinar, A.; Sehgal, M.; Rossomacha, E.; Datta, P.; Sharma, A.; Gandhi, R.; Kapoor, M.; et al. Inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling ameliorates osteoarthritis in a murine model of experimental osteoarthritis. JCI Insight 2018, 3, 96308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigout, A.; Werkmann, D.; Menges, S.; Brenneis, C.; Henson, F.; Cowan, K.J.; Musil, D.; Thudium, C.S.; Gühring, H.; Michaelis, M.; et al. R399E, A Mutated Form of Growth and Differentiation Factor 5, for Disease Modification of Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022, 75, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, W.R.; Byers, B.A.; Su, D.; Geesin, J.; Herzberg, U.; Wadsworth, S.; Bendele, A.; Story, B. Intra-articular therapy with recombinant human GDF5 arrests disease progression and stimulates cartilage repair in the rat medial meniscus transection (MMT) model of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2017, 25, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkiraju, H.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Xu, X.; Jia, X.; Safran, C.B.K.; Nohe, A.; Akkiraju, H.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Xu, X.; Jia, X.; et al. CK2.1, a bone morphogenetic protein receptor type Ia mimetic peptide, repairs cartilage in mice with destabilized medial meniscus. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcu, K.B.; Otero, M.; Olivotto, E.; Borzi, R.M.; Goldring, M.B. NF-κB Signaling: Multiple Angles to Target OA. Curr. Drug Targets 2010, 11, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Mathews, L.A.; Cabarcas, S.M.; Zhang, X.; Yang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Young, M.R.; Klarmann, K.D.; Keller, J.R.; Farrar, W.L. Epigenetic Regulation of SOX9 by the NF-κB Signaling Pathway in Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 1454–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Wu, S.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.-P.; Wu, M.; Wu, S.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.-P. The roles and regulatory mechanisms of TGF-β and BMP signaling in bone and cartilage development, homeostasis and disease. Cell Res. 2024, 34, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratovic, D.; Atkins, G.J.; Findlay, D.M. Is RANKL a potential molecular target in osteoarthritis? Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2023, 32, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Liu, L.; Feng, H.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, H. Therapeutics of osteoarthritis and pharmacological mechanisms: A focus on RANK/RANKL signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 167, 115646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, X.; Xing, L.; Tian, F.; Wang, Y.; Fan, X.; Xing, L.; Tian, F. Wnt signaling: A promising target for osteoarthritis therapy. Cell Commun. Signal. 2019, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.-C.; Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.-C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.-C.; Jo, J.; Park, J.; Kang, H.K.; Park, Y.; Choi, M.-C.; Jo, J.; Park, J.; Kang, H.K.; Park, Y. NF-κB Signaling Pathways in Osteoarthritic Cartilage Destruction. Cells 2019, 8, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, P.J. How corticosteroids control inflammation: Quintiles Prize Lecture 2005. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 148, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasova, K.; Arteaga, M.B.; Kidtiwong, A.; Gueltekin, S.; Bileck, A.; Gerner, C.; Gerner, I.; Jenner, F.; Tarasova, K.; Arteaga, M.B.; et al. Dexamethasone: A double-edged sword in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salis, Z.; Sainsbury, A.; Salis, Z.; Sainsbury, A. Association of long-term use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with knee osteoarthritis: A prospective multi-cohort study over 4-to-5 years. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Li, F.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.G.; Zhang, B. TNF-α and RANKL promote osteoclastogenesis by upregulating RANK via the NF-κB pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 6605–6611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicco, G.D.; Marzano, E.; Mastrostefano, A.; Pitocco, D.; Castilho, R.S.; Zambelli, R.; Mascio, A.; Greco, T.; Cinelli, V.; Comisi, C.; et al. The Pathogenetic Role of RANK/RANKL/OPG Signaling in Osteoarthritis and Related Targeted Therapies. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monasterio, G.; Castillo, F.; Rojas, L.; Cafferata, E.A.; Alvarez, C.; Carvajal, P.; Núñez, C.; Flores, G.; Díaz, W.; Vernal, R. Th1/Th17/Th22 immune response and their association with joint pain, imagenological bone loss, RANKL expression and osteoclast activity in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis: A preliminary report. J. Oral Rehabil. 2018, 45, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, K.; Tu, F.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H. Synovial fibroblasts regulate the cytotoxicity and osteoclastogenic activity of synovial natural killer cells through the RANKL-RANK axis in osteoarthritis. Scand. J. Immunol. 2021, 94, e13069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadri, A.; Ea, H.K.; Bazille, C.; Hannouche, D.; Lioté, F.; Cohen-Solal, M.E. Osteoprotegerin inhibits cartilage degradation through an effect on trabecular bone in murine experimental osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58, 2379–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kraan, P.M. Differential Role of Transforming Growth Factor-beta in an Osteoarthritic or a Healthy Joint. J. Bone Metab. 2018, 25, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Li, S.; Chen, D.; Shen, J.; Li, S.; Chen, D. TGF-β signaling and the development of osteoarthritis. Bone Res. 2014, 2, 14002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowery, J.W.; Rosen, V. The BMP Pathway and Its Inhibitors in the Skeleton. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 2431–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Tian, G.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, F.; Tian, Z.; Huang, B.; Wei, F.; Zha, K.; Sun, Z.; et al. Research Progress on Stem Cell Therapies for Articular Cartilage Regeneration. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 8882505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catherine, B.; Nicolas, G.; Eva, L.; Celine, B.; Karim, B.; Catherine, B.; Nicolas, G.; Eva, L.; Celine, B.; Karim, B. Regulation and Role of TGFβ Signaling Pathway in Aging and Osteoarthritis Joints. Aging Dis. 2014, 5, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.H.; Li, Y.S.; Gao, X.; Lei, G.H.; Huard, J. Bone morphogenetic proteins for articular cartilage regeneration. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2018, 26, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hou, R.; Yin, R.; Yin, W. Correlation of Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 Levels in Serum and Synovial Fluid with Disease Severity of Knee Osteoarthritis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2015, 21, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Lou, Q.; Wang, L.; Min, S.; Zhao, M.; Quan, C.; Zhang, X.; Lou, Q.; Wang, L.; Min, S.; et al. Immobilization of BMP-2-derived peptides on 3D-printed porous scaffolds for enhanced osteogenesis. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 15, 015002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayas, R.; Reyes, R.; Arnau, M.R.; Évora, C.; Delgado, A. Injectable Scaffold for Bone Marrow Stem Cells and Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 to Repair Cartilage. Cartilage 2019, 12, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neefjes, M.; van Caam, A.P.M.; van der Kraan, P.M. Transcription Factors in Cartilage Homeostasis and Osteoarthritis. Biology 2020, 9, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Kim, D.J.; Shen, J.; Zou, Z.; O’Keefe, R.J. Runx2 plays a central role in Osteoarthritis development. J. Orthop. Transl. 2020, 23, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furumatsu, T.; Ozaki, T.; Asahara, H. Smad3 activates the Sox9-dependent transcription on chromatin. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Zheng, Q.; Engin, F.; Munivez, E.; Chen, Y.; Sebald, E.; Krakow, D.; Lee, B.; Zhou, G.; Zheng, Q.; et al. Dominance of SOX9 function over RUNX2 during skeletogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 19004–19009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wan, X.; Le, Q. Cross-regulation between SOX9 and the canonical Wnt signalling pathway in stem cells. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1250530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, B.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, J.; Kang, X. The role of NF-κB-SOX9 signalling pathway in osteoarthritis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liacini, A.; Sylvester, J.; Li, W.Q.; Huang, W.; Dehnade, F.; Ahmad, M.; Zafarullah, M. Induction of matrix metalloproteinase-13 gene expression by TNF-α is mediated by MAP kinases, AP-1, and NF-κB transcription factors in articular chondrocytes. Exp. Cell Res. 2003, 288, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, A.J.; Davis, R.J.; Whitmarsh, A.J.; Davis, R.J. Transcription factor AP-1 regulation by mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways. J. Mol. Med. 1996, 74, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Lu, Y.; Rothrauff, B.B.; Zheng, A.; Lamb, A.; Yan, Y.; Lipa, K.E.; Lei, G.; Lin, H. Mechanotransduction pathways in articular chondrocytes and the emerging role of estrogen receptor-α. Bone Res. 2023, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Lloris, R.; Viñals, F.; López-Rovira, T.; Harley, V.; Bartrons, R.; Rosa, J.L.; Ventura, F. Induction of the Sry-related factor SOX6 contributes to bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced chondroblastic differentiation of C3H10T1/2 cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003, 17, 1332–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Smits, P.; Dy, P.; Mitra, S.; Lefebvre, V. Sox5 and Sox6 are needed to develop and maintain source, columnar, and hypertrophic chondrocytes in the cartilage growth plate. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 164, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehentner, B.K.; Dony, C.; Burtscher, H. The transcription factor Sox9 is involved in BMP-2 signaling. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 1999, 14, 1734–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrmann, C.; Brockmueller, A.; Mueller, A.-L.; Shayan, P.; Shakibaei, M. Curcumin Attenuates Environment-Derived Osteoarthritis by Sox9/NF-kB Signaling Axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira Mendes, A.; Caramona, M.M.; Carvalho, A.P.; Lopes, M.C.; Ferreira Mendes, A.; Caramona, M.M.; Carvalho, A.P.; Lopes, M.C. Hydrogen peroxide mediates interleukin-1β-induced AP-1 activation in articular chondrocytes: Implications for the regulation of iNOS expression. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2003, 19, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thielen, N.G.M.; Neefjes, M.; Vitters, E.L.; van Beuningen, H.M.; Blom, A.B.; Koenders, M.I.; van Lent, P.L.E.M.; van de Loo, F.A.J.; Davidson, E.N.B.; van Caam, A.P.M.; et al. Identification of Transcription Factors Responsible for a Transforming Growth Factor-β-Driven Hypertrophy-like Phenotype in Human Osteoarthritic Chondrocytes. Cells 2022, 11, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristou, D.; Batistatou, A.; Sykiotis, G.; Varakis, I.; Papavassiliou, A. Activation of the JNK-AP-1 signal transduction pathway is associated with pathogenesis and progression of human osteosarcomas. Bone 2003, 32, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Cho, C.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.J.; Park, H.; Yu, J.H.; Lee, S.; Lee, K.-S.; et al. Blockade of the vaspin–AP-1 axis inhibits arthritis development. Exp. Mol. Med. 2025, 57, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motomura, H.; Seki, S.; Shiozawa, S.; Aikawa, Y.; Nogami, M.; Kimura, T. A selective c-Fos/AP-1 inhibitor prevents cartilage destruction and subsequent osteophyte formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 497, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamad, D.W.; Bensreti, H.; Dorn, J.; Hill, W.D.; Hamrick, M.W.; McGee-Lawrence, M.E. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-mediated signaling as a critical regulator of skeletal cell biology. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2022, 69, R109–R124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Jia, C.; Yang, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, B.; Wei, W.; Chang, Y. Activation of the kynurenine-aryl hydrocarbon receptor axis impairs the chondrogenic and chondroprotective effects of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in osteoarthritis rats. Hum. Cell 2022, 36, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheijen, B.; Bronk, M.; van de Meer, T.; Bernards, R. Constitutive E2F1 Overexpression Delays Endochondral Bone Formation by Inhibiting Chondrocyte Differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 3656–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pellicelli, M.; Picard, C.; Wang, D.; Lavigne, P.; Moreau, A. E2F1 and TFDP1 Regulate PITX1 Expression in Normal and Osteoarthritic Articular Chondrocytes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.-M.; Lu, X.-H.; Lin, J.; Hu, J.; Rong, Z.-J.; Xu, W.-C.; Liu, Z.-W.; Zeng, W.-T. Knockdown of FOXM1 attenuates inflammatory response in human osteoarthritis chondrocytes. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 68, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Lu, X.; Lin, J.; Ron, Z.; Fang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, W. FOXM1 activates JAK1/STAT3 pathway in human osteoarthritis cartilage cell inflammatory reaction. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 246, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Huang, H.; Pan, X.; Li, S.; Xie, Z.; Ma, Y.; Hu, B.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Shi, P. EGR1 promotes the cartilage degeneration and hypertrophy by activating the Krüppel-like factor 5 and β-catenin signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 2490–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zhan, W.; Chen, M.; Ruan, J.; Shen, C. VEGFA, MYC, and JUN are abnormally elevated in the synovial tissue of patients with advanced osteoarthritis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Quickelberghe, E.; De Sutter, D.; van Loo, G.; Eyckerman, S.; Gevaert, K.; Van Quickelberghe, E.; De Sutter, D.; van Loo, G.; Eyckerman, S.; Gevaert, K. A protein-protein interaction map of the TNF-induced NF-κB signal transduction pathway. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catheline, S.E.; Bell, R.D.; Oluoch, L.S.; James, M.N.; Escalera-Rivera, K.; Maynard, R.D.; Chang, M.E.; Dean, C.; Botto, E.; Ketz, J.P.; et al. IKKβ-NF-κB signaling in adult chondrocytes promotes the onset of age-related osteoarthritis in mice. Sci. Signal. 2021, 14, eabf3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, C.; Bai, X.; Pan, C.; Cai, D.; et al. Carpaine ameliorates synovial inflammation by promoting p65 degradation and inhibiting the NF-κB signalling pathway. Bone Jt. Res. 2025, 14, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, O.-J.; Kim, H.-J.; Woo, K.-M.; Baek, J.-H.; Ryoo, H.-M. FGF2-activated ERK Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Enhances Runx2 Acetylation and Stabilization. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 3568–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Li, Y.; Shang, C.; Shang, G.; Kou, H.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Liu, H. Sprifermin: Effects on Cartilage Homeostasis and Therapeutic Prospects in Cartilage-Related Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 786546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.-F.; O’Keefe, R.J.; Chen, D. TGF-β signaling in chondrocytes. Front. Biosci. A J. Virtual Libr. 2005, 10, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kraan, P.M. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-β in osteoarthritis. Discrepancy with reduced TGFβ signaling in normal joints. Osteoarthr. Cartil. Open 2022, 4, 100238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Sun, M.; Zhang, X. Protective Effect of Resveratrol on Knee Osteoarthritis and its Molecular Mechanisms: A Recent Review in Preclinical and Clinical Trials. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 921003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, C.; Moran, D.; Jamieson, V.; Spence, S.; Hill, S. A multicentre study of tenoxicam for the treatment of osteo-arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in general practice. J. Int. Med. Res. 1990, 18, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.L.; Murphy, C.L. HIF-2α—A mediator of osteoarthritis? Cell Res. 2010, 20, 977–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Arai, Y.; Kishida, T.; Terauchi, R.; Honjo, K.; Nakagawa, S.; Tsuchida, S.; Matsuki, T.; Ueshima, K.; Fujiwara, H.; et al. Hydrostatic Pressure Influences HIF-2 Alpha Expression in Chondrocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkiewicz, M.; Doyle, J.L.; Fudalewski, T.; Ispanovic, E.; Aghasi, M.; Haas, T.L. HIF-1α and HIF-2α play a central role in stretch-induced but not shear-stress-induced angiogenesis in rat skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2007, 583, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Tian, W. Elevated expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha regulated catabolic factors during intervertebral disc degeneration. Life Sci. 2019, 232, 116565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copp, G.; Robb, K.P.; Viswanathan, S.; Copp, G.; Robb, K.P.; Viswanathan, S. Culture-expanded mesenchymal stromal cell therapy: Does it work in knee osteoarthritis? A pathway to clinical success. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 626–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Huang, J.; Jiao, Z.; Nian, M.; Li, C.; Dai, Y.; Jia, S.; Zhang, X. Mesenchymal stem cells for osteoarthritis: Recent advances in related cell therapy. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2024, 10, e10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santolini, M.; Rios, J.L.; Custers, R.J.H.; Creemers, L.B.; Korpershoek, J.V. Mesenchymal stromal cell injections for osteoarthritis: In vitro mechanisms of action and clinical evidence. Knee 2025, 56, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cheng, R.-J.; Wu, Y.; Huang, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Advances in Stem Cell-Based Therapies in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthu, S.; Patil, S.C.; Jeyaraman, N.; Jeyaraman, M.; Gangadaran, P.; Rajendran, R.L.; Oh, E.J.; Khanna, M.; Chung, H.Y.; Ahn, B.-C. Comparative effectiveness of adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in the management of knee osteoarthritis: A meta-analysis. World J. Orthop. 2023, 14, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfstadt, J.I.; Cole, B.J.; Ogilvie-Harris, D.J.; Viswanathan, S.; Chahal, J. Current Concepts: The Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis. Sports Health 2014, 7, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wu, W.; Qu, X. Mesenchymal stem cells in osteoarthritis therapy: A review. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 448–461. [Google Scholar]

- Minas, T.; Gomoll, A.H.; Solhpour, S.; Rosenberger, R.; Probst, C.; Bryant, T. Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation for Joint Preservation in Patients with Early Osteoarthritis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2010, 468, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wright, K.T.; Perry, J.; Tins, B.; Hopkins, T.; Hulme, C.; McCarthy, H.S.; Brown, A.; Richardson, J.B. Combined Autologous Chondrocyte and Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Implantation in the Knee: An 8-year Follow Up of Two First-In-Man Cases. Cell Transplant. 2019, 28, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossendorf, C.; Steinwachs, M.R.; Kreuz, P.C.; Osterhoff, G.; Lahm, A.; Ducommun, P.P.; Erggelet, C. Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) for the treatment of large and complex cartilage lesions of the knee. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rehabil. Ther. Technol. SMARTT 2011, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Lim, R.; Owens, B.D. Latest Advances in Chondrocyte-Based Cartilage Repair. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowley, J.L.; Soti, V. Platelet-Rich Plasma Therapy: An Effective Approach for Managing Knee Osteoarthritis. Cureus 2023, 15, e50774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronesi, F.; Torricelli, P.; Giavaresi, G.; Sartori, M.; Cavani, F.; Setti, S.; Cadossi, M.; Ongaro, A.; Fini, M. In vivo effect of two different pulsed electromagnetic field frequencies on osteoarthritis. J. Orthop. Res. 2014, 32, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseychuk, O.; Akkiraju, H.; Dutta, J.; D’Angelo, A.; Bragdon, B.; Duncan, R.L.; Nohe, A. Inhibition of CK2 binding to BMPRIa induces C2C12 differentiation into osteoblasts and adipocytes. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2013, 7, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Bao, R.; Wei, P.; Bao, R. Intra-Articular Mesenchymal Stem Cell Injection for Knee Osteoarthritis: Mechanisms and Clinical Evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, L.A.; Ahmed, G.; Dakin, S.G.; Kendrick, B.; Price, A.; Salman, L.A.; Ahmed, G.; Dakin, S.G.; Kendrick, B.; Price, A. Osteoarthritis: A narrative review of molecular approaches to disease management. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2023, 25, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimedx Group, Inc. Protocol for the Clinical Evaluation Amniotic Fluid (AF) Product in Knee Osteoarthritis. Clinical trials.gov, Identifier: NCT02768155. Posted May 11, 2016. Updated October 2017. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02768155 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Redeker, J.I.; Schmitt, B.; Grigull, N.P.; Braun, C.; Büttner, A.; Jansson, V.; Mayer-Wagner, S.; Redeker, J.I.; Schmitt, B.; Grigull, N.P.; et al. Effect of electromagnetic fields on human osteoarthritic and non-osteoarthritic chondrocytes. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Xie, W.; Ye, W.; He, C. Effects of electromagnetic fields on osteoarthritis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 118, 109282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.E.; Malfait, A.M.; Block, J.A. Current status of nerve growth factor antibodies for the treatment of osteoarthritis pain. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2017, 35, 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Akkiraju, H.; Bonor, J.; Nohe, A. CK2.1, a novel peptide, induces articular cartilage formation in vivo. J. Orthop. Res. 2016, 35, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, X.; Gu, J.; Chen, M.; Zhao, F.; Aili, M.; Zhang, D. Multiple roles of ALK3 in osteoarthritis: A narrative review. Bone Jt. Res. 2023, 12, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Seo, J.; Lee, Y.; Park, K.; Perry, T.A.; Arden, N.K.; Mobasheri, A.; Choi, H. The current state of the osteoarthritis drug development pipeline: A comprehensive narrative review of the present challenges and future opportunities. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2022, 14, 1759720X221085952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.H.; Seo, J.; Lee, Y.; Park, K.; Kim, K.-R.; Kim, S.; Mobasheri, A.; Choi, H. TissueGene-C induces long-term analgesic effects through regulation of pain mediators and neuronal sensitization in a rat monoiodoacetate-induced model of osteoarthritis pain. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2023, 31, 1567–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, R.M.; Bliddal, H.; Blanco, F.J.; Schnitzer, T.J.; Peterfy, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, L.; Feng, S.; Conaghan, P.G.; Berenbaum, F.; et al. A Phase II Trial of Lutikizumab, an Anti–Interleukin-1α/β Dual Variable Domain Immunoglobulin, in Knee Osteoarthritis Patients with Synovitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 1056–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Hu, B.; Hu, S.; Zhang, X.; Hu, J. Small molecule inhibitors of osteoarthritis: Current development and future perspective. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1156913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unity Biotechnology, Inc. A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study of Single and Repeat Dose Administration of UBX0101 in Moderate to Severe, Painful Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Clinical trials.gov, Identifier: NCT04229225. Updated October 19, 2020. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04229225 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Chin, A.F.; Han, J.; Clement, C.C.; Choi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Browne, M.; Jeon, O.H.; Elisseeff, J.H. Senolytic treatment reduces oxidative protein stress in an aging male murine model of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Aging Cell 2023, 22, e13979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Huang, K.; Ji, B.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Ma, J.; Shen, S.; Zhang, J. miR-10a-5p Promotes Chondrocyte Apoptosis in Osteoarthritis by Targeting HOXA1. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2019, 14, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Lu, J.; Wu, Y.; Xu, H. MiR-18a-3p improves cartilage matrix remodeling and inhibits inflammation in osteoarthritis by suppressing PDP1. J. Physiol. Sci. JPS 2022, 72, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.S.; Park, S.J.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, H.A.; Hwang, H.S.; Park, S.J.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, H.A. MicroRNA-365 regulates IL-1β-induced catabolic factor expression by targeting HIF-2α in primary chondrocytes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, Z.; Pi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Mei, L.; Luo, Y.; Xie, J.; Mao, X. MicroRNA-375 exacerbates knee osteoarthritis through repressing chondrocyte autophagy by targeting ATG2B. Aging 2020, 12, 7248–7261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pathway | Role in OA | Relevant Treatments | Related Transcription Factors | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WNT | Promote chondrocyte hypertrophy and differentiation, joint homeostasis [43] | XAV939 (preclinical) | Lymphoid enhancer-binding factor/T-cell Factor (LEF/TCF) family | [43,44] |

| Bone morphogenetic protein/SMAD | Chondrocyte hypertrophy, MSC differentiation into chondrocytes | CK2.1 (Preclinical), GDF5 (Preclinical), R399E (Preclinical) | SMADs | [45,46,47] |

| Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) | Joint inflammation, chondrocyte catabolism | Aspirin, glucocorticoids (interfere with downstream effects of NF-κB) | RUNX2, SOX9, AP-1 | [48,49] |

| Transforming Growth Factor | Chondrocyte homeostasis, differentiation, hypertrophy, cartilage degradation | TissueGene-C (Late clinical trials) | AP-1, SOX9 | [50] |

| Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B (RANK) and RANK ligand (RANKL) | Various, the most significant effect seems to be in bone remodeling and inflammation | Denosumab (Ongoing clinical trials) | NF-κB | [51,52] |

| Transcription Factor | Related Signaling Molecules and Pathways | Function | Relevant Tissue/Cell Type | Related Treatments in Development/Research Relevant to OA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRY box transcription factor 6 (SOX6) | Bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) [82] | Chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation [83] | Articular Cartilage, synovial membrane | - |

| SRY box transcription factor 9 (SOX9) | BMPs, [84] Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) [75] | Chondrogenesis master regulator [73] | Articular cartilage | SOX9 protein delivery, Curcumin (early clinical, based on traditional Chinese medicine) [85] |

| Activator protein 1 (AP1) | Reactive oxygen species, Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), [86], mechanical stress [81], Mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK), NF-κB, TGF-β, [87] c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway [88] | Regulates genes involved in cartilage breakdown [89] and inflammation, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) production, WNT signaling | Chondrocytes, synovial membrane, subchondral bone | T-5224 (Preclinical) [90] |

| Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) | Kynurenine pathway [91] | Impairs chondrogenic/chondroprotective effects [92]; regulation of skeletal progenitor cells [91]; immune regulation [92] | Cartilage, Bone | - |

| E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F1) | Various | Chondrocyte differentiation [93] | Chondrocytes | - |

| Pituitary homeobox transcription factor 1 (PITX1) | E2F1, Transcription factor Dp-1 (TFDP1) [94] | Inhibit senescence [73] | Cartilage | - |

| Forkhead box protein M1 (FOXM1) | IL-1β [95] | Activates Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT), regulates genes that regulate cartilage degradation [96], WNT signaling, and apoptosis | Chondrocytes | - |

| Early growth response 1 (EGR1) | IL-1β [97] | Activates β-Catenin pathway, increases MMPs in response to inflammatory cytokines in OA; accelerates hypertrophy [97] | Cartilage, synovial tissue | - |

| MYC | Unclear | Unclear, elevated levels associated with worse disease progression [98] | Primarily synovial tissue | - |

| RELA (p65) key subunit of NF-κB | TNF [99], IL-1β, IL-6, [55] Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) [100] | Subunit of NF-κB, regulates inflammation, catabolic, and pro-inflammatory phenotypes | Chondrocytes, synovial tissue [101] | Multiple drugs that inhibit downstream effects of NF-κB are already available, like aspirin and glucocorticoid injections. |

| Runtrelated transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) | Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) [102], Indirectly activated by SMAD 1/5/8 [73] | Major switch for chondrocyte differentiation into the hypertrophic state. controls the expression of MMPs, aggrecanases [74] | Chondrocytes | Sprifermin [103] |

| SMADS | TGF-β [104] BMP [104] | Chondrocyte homeostasis, inflammation | Chondrocytes, articular cartilage | TGF-β inhibitors, [105] SMIs, Resveratrol [106], Tenoxicam [107] |

| Hypoxia-inducible factor 2 alpha (HIF-2α) | IL-1β [108] mechanical stress, [109,110] NF-κB [111] | Promotes catabolic activity, expression of MMP-13 [111] | Chondrocytes | - |

| Drug/Treatment | Target Pathway | Proposed Mechanism | Effect | Development Status | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) injections | Immune/inflammatory modulation Anti-apoptosis | Suppress interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), Interleukin-6 (IL-6) Differentiation into different cells in the joint Secrete B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) and Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) | Seems to have a generally positive effect on regeneration potential. Supplies healthier MSCs to support chondrogenesis and immune regulation | Late clinical trials | [120,126,127] |

| Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI) | Does not directly target the pathway | Implant the patient’s own healthy chondrocytes into the damaged joint | Reduced pain, improved joint function | FDA approved for specific cases in younger patients usually following acute injury. Not generally considered a primary treatment for osteoarthritis (OA) | [119] |

| Amniotic fluid injection | Does not directly target the pathway | Immunomodulation | Mixed, inconclusive results | Mid-stage clinical trials, labelled as “investigational” by the FDA | [128] |

| Plasma PRP | Does not directly target the pathway | Introduce various growth factors to induce regeneration that would otherwise not be accessible to the avascular tissue. | Seems to slow disease progression | Mid–late clinical trials labeled as “investigational” by the FDA. Legally can be applied “off label” because the FDA does not have the authority to regulate a person’s own bodily products. | [123] |

| Pulsed electromagnetic frequency (PEMF) | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), possibly Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) | Increases adenosine receptors A2A, A3 expression, suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokine release, and increases Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) secretion. Increases, express anti-apoptotic proteins | Results are mixed. Some sources claim it suppresses cartilage degeneration and enhances chondrocyte differentiation | Inconclusive. Several devices are approved for specific applications, not generally linked to OA. | [124,129,130] |

| Nerve growth factor (NGF) Blockade | Neurotrophin signaling | Blocking the effect of NGF, which stimulates nerve growth and is connected to acute and chronic pain | Promising symptom reduction, however, with the risk of inducing rapid progression of the disease | Clinical development stalled due to concerns of causing the rapid progression of OA | [131] |

| CK2.1 | BMP | Unknown | Stimulates chondrogenesis and cartilage repair, without hypertrophy | Preclinical | [132] |

| R399E 1 | BMP | Induction of aggrecan and SRY-box transcription factor 9 (SOX9); reduced collagen X; lower cartilage hypertrophy and osteogenic activity; cartilage repair | Cartilage structure improvement | Preclinical | [45,133] |

| GDF5 2 | BMP | Induction of aggrecan and SOX9; reduced collagen X; cartilage repair. Can also form osteophytes | Maintain cartilage homeostasis | Preclinical | [46,133] |

| Sprifermin | FGF-18 homologue | Binds to FGF3R, signals through Mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) to regulate Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) | Sustained anabolic effect on cartilage. Structural improvements | Completed phase 2 clinical trials. Inconsistent symptom relief in phase 2 has stalled any phase 3 trials | [103,134] |

| Tissue Gene-C (TG-C) | TGF-β1 | Inject chondrocytes and cells that overexpress TGF-β 1. Synthesize cartilage components | Improved OA metric scores | Late clinical, preparing for completion | [134,135] |

| Lutikizumab | Block interleukin 1α and 1β | Binds to inflammatory cytokines IL-1α and 1β | Improved pain score, did not affect the structural score | Discontinued for the treatment of OA after phase 2 clinical, now being considered for other inflammatory conditions | [136] |

| Denosumab | Receptor activator of NF-kappa B (RANK) and ligand of RANK (RANKL) (Related to NF-κB) | Bands to RANKL, preventing its activation of the RANK receptor | Reduces chondrocyte apoptosis, bone resorption. Reduces bone and cartilage degradation | Phase 2 ongoing | [51] |

| T-5224 | Upstream regulation of proteases and inflammatory cytokines | C-Fos/Activator protein 1 (AP-1) inhibitor | Protects cartilage, reduces osteophyte formation | Preclinical | [90] |

| XAV-939 | WNT inhibition | Inhibition of WNT by anticatabolic effects on chondrocytes, antifibrotic effects on synovial fibroblasts | Reduced OA severity | Preclinical | [44,137] |

| UBX0101 | DNA damage response, proapoptotic pathway | Inhibit p53/Murine duble minute 2 (MDM2) interaction, senolytic, remove senescent cells to reverse OA pathology | Promising animal model results failed to meet efficacy goals in human trials | Discontinued in phase 2 | [138,139] |

| AntagomiR-10a-5p | Homeobox gene HoxA1 | Interferes with the silencing of HOXA1 by miR-10a-5p | Suppresses IL-1β induced apoptosis | Preclinical | [140] |

| miR-18A3p | NF-κB | Binds to and negatively regulated Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Phosphatase 1 (PDP1) expression. | Improves matrix remodeling and suppresses inflammation | Preclinical | [141] |

| miR-365 | IL-1β | Possibly binds to Hypoxia-inducible factor 2 alpha (HIF-2α), suppresses IL-1β-induced expression of HIF-2α | Prevents MMP-13 expression in primary cultured chondrocytes, protecting cartilage from degradation in OA microenvironment | Preclinical | [142] |

| Antagomir of miR-375 | ATG-2B, a key autophagy gene | The antagomir inhibits mIR-375 from inhibiting ATG-2B, and thus it reduces apoptosis, promotes autophagy | Reduces apoptosis, promotes autophagy in mouse model | Preclinical | [143] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fracek, L.; Patel, A.; Pandit, V.; Tanim, M.T.H.; Nohe, A. Emerging Insights into the Molecular Basis of Osteoarthritis Pathogenesis and Treatment Strategies. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010050

Fracek L, Patel A, Pandit V, Tanim MTH, Nohe A. Emerging Insights into the Molecular Basis of Osteoarthritis Pathogenesis and Treatment Strategies. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010050

Chicago/Turabian StyleFracek, Luke, Aarushi Patel, Venu Pandit, Md Tamzid Hossain Tanim, and Anja Nohe. 2026. "Emerging Insights into the Molecular Basis of Osteoarthritis Pathogenesis and Treatment Strategies" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010050

APA StyleFracek, L., Patel, A., Pandit, V., Tanim, M. T. H., & Nohe, A. (2026). Emerging Insights into the Molecular Basis of Osteoarthritis Pathogenesis and Treatment Strategies. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010050