A Monte Carlo Based Method for Assessing Energy-Related Operational Risks in Railway Undertakings

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Technical capabilities for transport operations—electricity enables efficient and reliable railway operations; deficits in availability (e.g., power outages), inadequate quality (e.g., significant voltage drops at the ends of sections supplied from different traction substations), or reduced technical parameters (e.g., during adverse weather conditions) may negatively affect railway operations; these impacts may manifest as reduced rolling stock reliability, lower punctuality of train services, and potential safety degradation, directly leading to financial losses for railway undertakings; such effects may be mitigated through advanced technologies in railway traffic organization (timetabling) and railway traffic control;

- Economic efficiency of the company—energy costs account for approximately 21.8% of the total operating costs of a railway undertaking [1], making them a significant cost component; railway operators therefore seek to reduce these costs through effective energy management measures, including monitoring actual energy consumption [2] (e.g., installation of on-board energy meters), the use of energy-saving systems [3], and regenerative braking; operators may also influence energy-related costs through the selection of energy suppliers and contractual arrangements for electricity procurement;

- Environmental and social profile of the company—the use of electricity as a traction energy carrier contributes to the implementation of the European Union’s climate policy; as a result, railway undertakings participate in the decarbonization of the transport sector [4] and operate in accordance with the principles of sustainable development.

2. Railway Undertaking Operations from an Electrical Perspective: A Literature Review

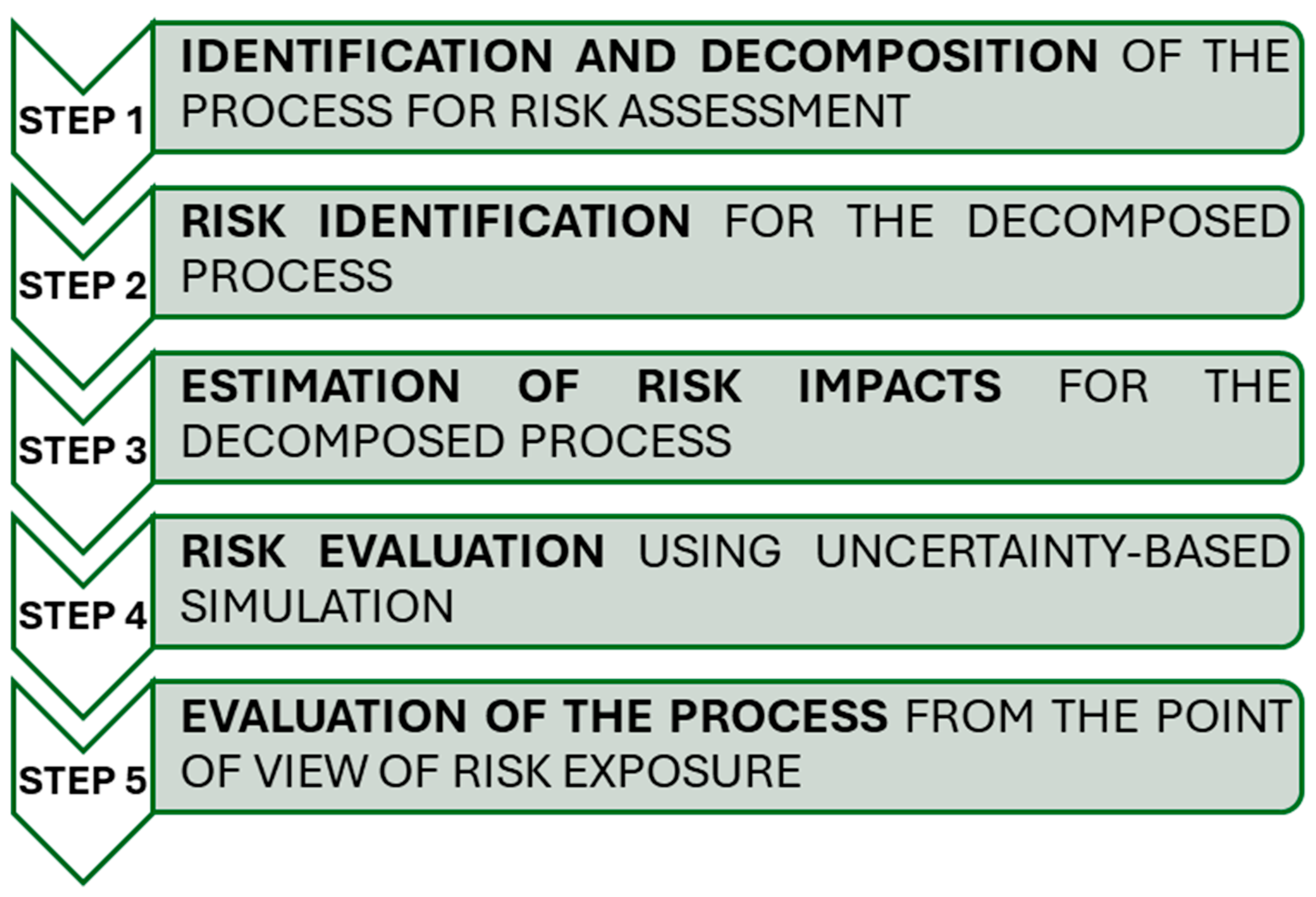

3. Method for Assessing the Risk of Railway Undertaking Operations from an Electrical Perspective

3.1. General Characteristics of the Method

- Identify: context (background of the problem) and risk (specific risks);

- Assess: estimate (estimating the probability, impact, and proximity of a given risk) and evaluate (evaluating the level of exposure to the risk of a given problem);

- Plan (develop a reaction to the materialization of risks);

- Implement (implement a reaction to risks and monitor the situation).

- Risks related to rolling stock;

- Risks related to energy infrastructure;

- Risks related to technical facilities;

- Risks related to transport organization and operation;

- Risks related to energy purchases;

- Risks related to external factors.

- Cause, i.e., an event that may cause a given risk to occur;

- Risk, i.e., an event which, if it occurs, may affect the achievement of the process objectives;

- Effect, i.e., the manner in which the process objectives are modified as a result of the materialization of a given risk.

- Total costs of the railway undertaking’s operations expressed in PLN/year;

- Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings expressed in PLN/year;

- Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort expressed in PLN/year;

- Costs related to electricity consumption by trains expressed in PLN/year;

- Profits related to the use of recuperation in the railway system expressed in PLN/year.

- G—set of risk group numbers,

- g—risk group number, g ∈ G, g ∈ ℕ,

- R(g)—set of risk numbers in group number g, g ∈ G,

- r—risk number, r ∈ ℕ,

- E(g,r)—expected value of risk number r belonging to group number g,

- P(g,r)—probability of occurrence of risk number r belonging to group number g,

- I(g,r)—impact of occurrence of risk number r belonging to group number g.

3.2. Assumptions for Risk Identification

- Risks related to rolling stock—this group of risks includes the consequences of electrical failures of traction vehicles that were assigned to operate a train and are no longer capable of continuing to operate, the consequences of the age of rolling stock (especially its electrical equipment), the consequences of damage to one or more traction vehicle components, which did not render them unfit for service, and failure to comply with eco-driving rules when driving traction vehicles;

- Risks related to energy infrastructure—this group of risks includes the consequences of damage to the catenary system at the operating control post or on the open line, the consequences of power supply interruptions in the catenary system, the consequences of power supply system overload, the consequences of the lack of energy recovery infrastructure, and the consequences of delays in the electrification of railway lines (consequences of not completing construction on time);

- Risks related to technical facilities—this group of risks includes the consequences of electrical failures in the technical facilities of railway undertakings, the consequences of using energy-intensive equipment in technical facilities, and the consequences of poor management of inventories of parts necessary for the repair of electric traction vehicles;

- Risks related to transport organization and operation—this group of risks includes the consequences of not having an electric traction vehicle with the appropriate parameters to operate a given train, the consequences of improper timetable scheduling from the point of view of energy recovery, excessive power consumption by electric traction vehicles, consequences of an electric traction vehicle breakdown at an operating control post or on the open line, and consequences of not installing eco-driving support devices in electric traction vehicles;

- Risks related to energy purchases—this group of risks includes the consequences of the economic situation in a given country and worldwide, especially on the energy market, and the consequences of delays in the electrification of railway lines (energy has been contracted but the infrastructure has not been built on time);

- Risks related to external factors—this group of risks includes the consequences of the economic situation in a given country and worldwide, especially on the energy market, the consequences of adverse weather conditions, the consequences of delays in the electrification of railway lines on the part of the contractor, and the consequences of a cyberattack on the power supply system.

3.3. Assumptions for Risk Estimation

- Total costs of the railway undertaking’s operations expressed in PLN/year

- The costs generated per passenger in 2024 amounted to 29.43 PLN/passenger [1].

- The number of passengers carried in 2024 amounted to approximately 407,533,000 passengers/year [1].

- Therefore, the total costs of passenger transport operations in 2024 amounted to approximately 12 billion PLN/year (11,993,696,190 PLN/year).

- The number of passenger trains operated in 2024 was 2,050,000 trains/year [1].

- As a result, the cost of operating a passenger train in 2024 was 5850.58 PLN/train.

- The operational work performed by passenger rail operators in 2024 amounted to 205,600,000 train-kilometers/year [1].

- Consequently, the distance traveled by passenger trains in 2024 amounted to 205,560,000 km/year.

- The average mileage of a passenger train is 100.29 km/train.

- The cost of operating one passenger train per kilometer in 2024 was 58.34 PLN/train-kilometer.

- Fuel accounts for 21.8% of the cost of operating a passenger train [1]—12.72 PLN/train-kilometer.

- Taking into account the average price of 1 MWh of energy needed for traction purposes (1400.9 PLN/MWh [1]) and the average price of m3 of fuel used for traction purposes (4874.2 PLN/m3 [1]), it can be estimated that the fuel component in the unit cost of operation can take a minimum value of 6.36 PLN/train-kilometer and a maximum value of 19.08 PLN/train-kilometer. This may result in the total costs of a passenger operator’s activities in 2024 ranging from 10,685,008,800 PLN/year to 13,299,732,000 PLN/year.

- 2.

- Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings expressed in PLN/year

- The number of passenger trains operated in 2024 was 2,050,000 trains/year [1].

- The punctuality rate for passenger trains in 2024 was 91.64% [1].

- The number of passenger trains running late in 2024 was therefore 171,380 trains.

- The average delay time for passenger trains in 2024 was 8.7 min/train [1].

- Compensation for each minute of delay, which the party causing the delay must pay to the party affected by the delay, in accordance with the Network Statement of the largest railway infrastructure manager in Poland—PKP Polskie Linie Kolejowe S.A., amounted to 5.85 PLN/min [62].

- The maximum compensation amount in 2024 was therefore 8,722,382.1 PLN/year.

- In an ideal situation, trains would run on schedule, so the total compensation amount could be 0 PLN/year, and the average amount would be 4,361,191.05 PLN/year.

- 3.

- Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort expressed in PLN/year

- Operational work that should have been performed by passenger trains in 2024, but was performed by replacement bus services, amounted to 3,800,000 train-kilometer [1].

- The cost of operating one passenger train per kilometer in 2024 was 58.34 PLN/train-kilometer.

- The cost of operating trains to carry out the above-mentioned operational work in 2024 would amount to approximately 221,673,373.16 PLN.

- The cost per vehicle-kilometer for bus transport in Poland is approximately 15 PLN/vehicle-km. As a result, the cost of the above-mentioned transport service would amount to approximately 57,000,000 PLN.

- The cost of reducing travel comfort can therefore be expressed as the difference between the cost of transport by train and by bus, i.e., approximately 164,692,000 PLN/year.

- Taking into account fluctuations in the cost per vehicle-kilometer in bus transport, it can be assumed that the minimum cost of reducing comfort would be 145,692,000 PLN/year, and the maximum 183,692,000 PLN/year.

- 4.

- Costs related to electricity consumption by trains expressed in PLN/year

- The total costs of passenger transport operations in 2024 amounted to approximately 12 billion PLN/year (11,993,696,190 PLN/year).

- Fuel accounts for 21.8% of passenger transport operators’ operating costs in 2024 [1], that is 2,614,625,769.42 PLN/year.

- In 2024, there were 1590 electric traction vehicles in operation, accounting for 78.4% of the market share [1]. Considering that the price of 1 m3 of diesel fuel is 3.48 times the price of 1 MWh of electricity, it can be assumed that the average electricity consumption costs are 2,049,866,603.23 PLN/year.

- It was assumed that costs may vary by +/−5%. Consequently, the minimum cost is approximately 1,947,373,273.07 PLN/year, and the maximum cost is approximately 2,152,359,933.39 PLN/year.

- 5.

- Profits related to the use of recuperation in the railway system expressed in PLN/year

- The average electricity consumption costs are 2,049,866,603.23 PLN/year.

- It was assumed that the profit from recuperation could be as follows: minimum 0% of costs (recuperation is not used), average 2.5%—51,246,665.08 PLN/year, and maximum 5%—102,493,330.16 PLN/year.

4. Risks of Railway Undertaking Operations from the Electrical Perspective—Results

4.1. Risk Identification

4.2. Risk Estimation

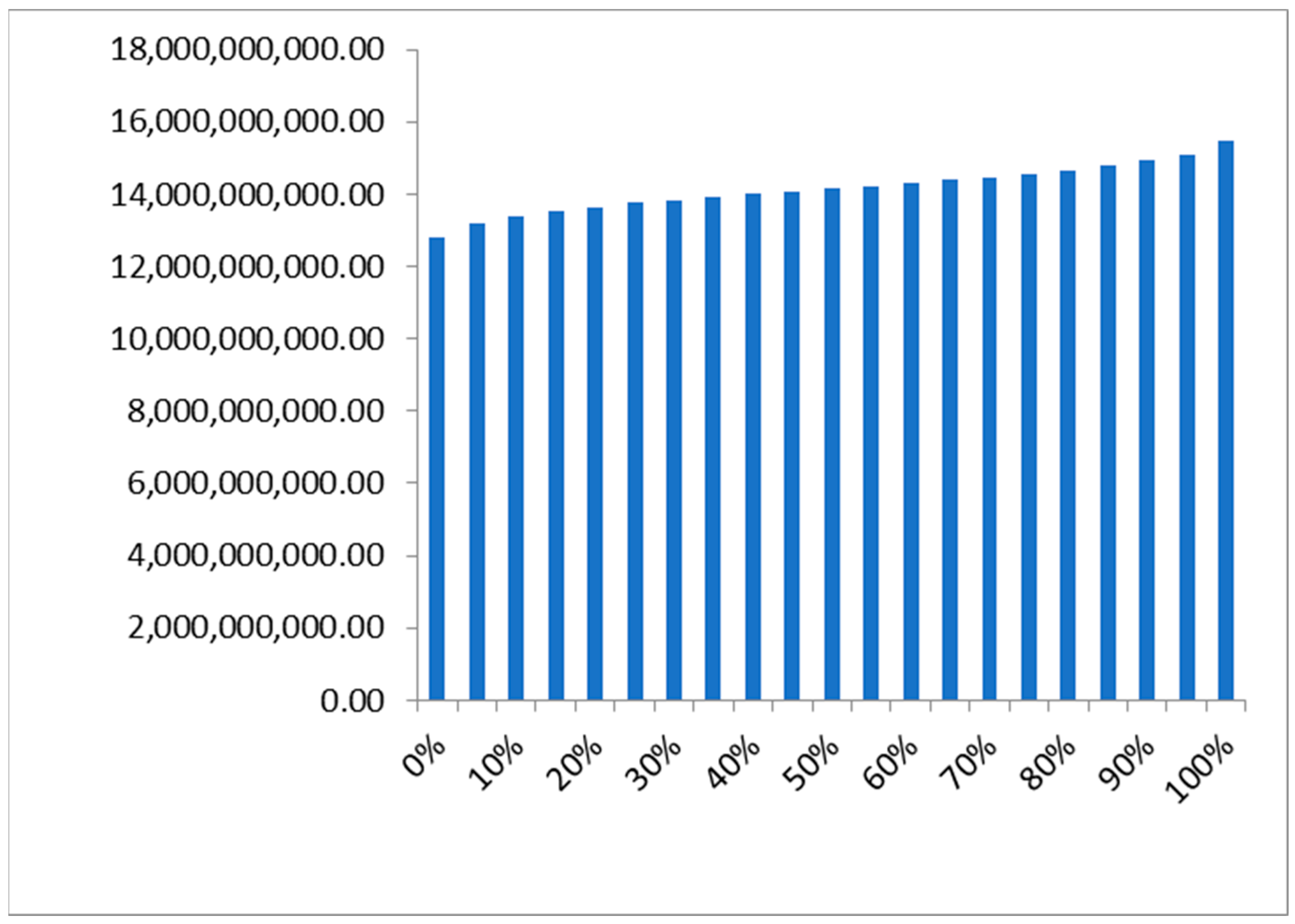

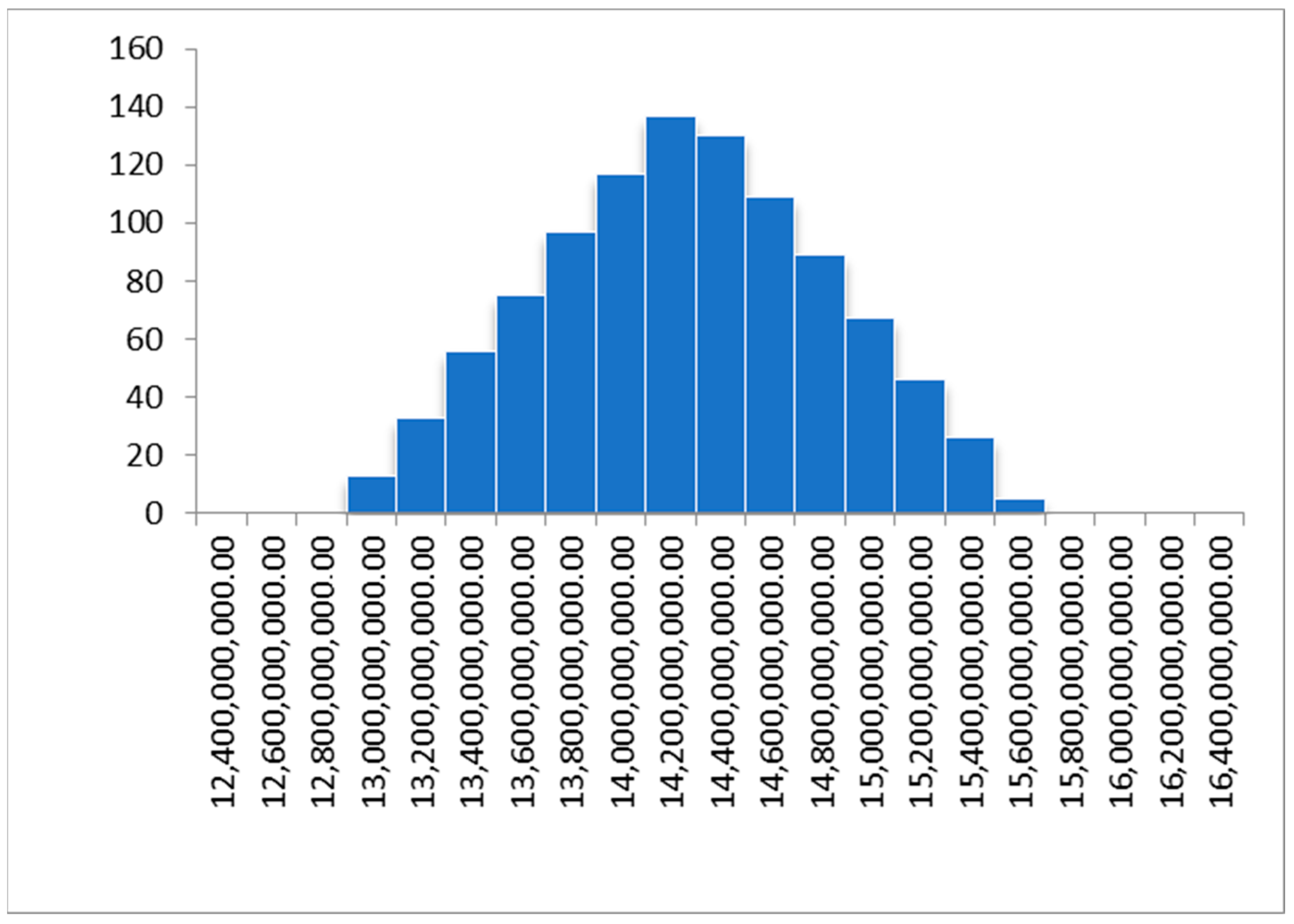

4.3. Risk Evaluation

5. Discussion: Assessment of the Risks of Railway Undertaking Operations from an Electrical Perspective

- Mean value—14,160,588,863.66 PLN/year;

- Number of trials—1000;

- Standard error—17,840,712.04 PLN/year;

- Minimum value—12,824,545,257.32 PLN/year;

- Maximum value—15,489,979,662.42 PLN/year;

- Median—14,159,617,595.70 PLN/year;

- Range—2,665,434,405.10 PLN/year;

- Standard deviation—564,455,149.31 PLN/year;

- Variance—318,609,615,576,962,000.00 (PLN/year)2;

- Skewness—0.00;

- Kurtosis—2.40.

6. Conclusions

- Identification of the process to be risk assessed and its decomposition into components;

- Identification of risks for the decomposed process;

- Estimation of risks for the decomposed process;

- Assessment of risks for the decomposed process;

- Evaluation of the process from the point of view of risk exposure.

- Some processes occurring at railway undertakings are complex; one such process is the operation of a railway undertaking from an electrical perspective; the results confirm that aggregated assessment obscures differences between risk categories, while process decomposition enables more differentiated and informative risk evaluation; this approach is therefore embedded in the method proposed in the article.

- The application of the risk description principle proposed by the M_o_R® methodology improves the interpretability and applicability of the results; identifying a set of causes makes it possible to better prevent the materialization of individual risks; identifying the effect facilitates their assessment.

- It is recommended to use publicly available data for risk assessment; this makes the developed method universal; changing the values of specific parameters that allow the national variable to be determined for individual countries will make it easy to compare risk exposure levels between countries; in addition, if the parameters are presented cyclically, it is easy to obtain national variable values for other periods of time; it should be noted that the universality of the proposed method refers to its structural framework and data requirements, rather than to uniform risk levels across countries; national specificities are captured through country-specific values of the adopted national variables.

- The use of a probabilistic risk model makes calculations more realistic; assigning an appropriate probability distribution to the national variable allows for the randomness of the materialization of individual risks to be reflected, thus enabling calculations that are close to reality; the use of this probabilistic risk model also has negative consequences, which is a general feature of model-based research; future research will focus on applying alternative probability distributions and comparing their results with those obtained using the triangular distribution in order to assess the sensitivity of the proposed method to distributional assumptions.

- The evaluation of the entire process from the point of view of risk exposure should be carried out in such a way that individual national variables are not included repeatedly in the calculations; using them once fully reflects issues related to the materialization of risks, and, in particular, the chances of making a profit or the risks of incurring a loss.

- Prioritize risk mitigation actions across different operational areas by comparing the simulated magnitude of potential losses and profits;

- Support cost-based decision-making by assessing how the materialization of specific energy-related risks may affect total operating costs;

- Identify critical sources of delay- and comfort-related losses, enabling targeted measures to reduce exposure to compensation claims and service quality degradation;

- Support strategic decisions on energy procurement and contracting, including risk-aware evaluation of electricity price volatility and market exposure;

- Assess the economic justification of investments in energy recovery systems and energy efficiency measures, based on the simulated profit potential;

- Although the empirical results are presented for the Polish railway market, the proposed framework is methodologically transferable and may be applied to other national contexts using country-specific input data.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Office of Rail Transport. Report on Rail Transport Market Operations 2024; The Office of Rail Transport: Warszawa, Poland, 2025.

- EN 50463-3; Railway Applications: Energy Measurement on Board Trains. Part 3, Data Handling. CENELEC: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- ISO 50001; Energy Management—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Chamaret, A.; Mannevy, P.; Clément, P.; Ernst, J.; Flerlage, H. Analysis, trends and expectations for low carbon railway. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 2684–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Government Commerce. Management of Risk: Guidance for Practitioners; AXELOS Ltd.: London, UK, 2010.

- Directive (EU) 2016/797 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2016 on the Interoperability of the Rail System Within the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02016L0797-20200528 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 1301/2014 of 18 November 2014 on the Technical Specifications for Interoperability Relating to the Energy Subsystem of the Rail System in the Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02014R1301-20230928 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Brenna, M.; Foiadelli, F.; Zaninelli, D. Electrical Railway Transportation Systems; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Profillidis, V. Railway Planning, Management, and Engineering; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, H.; Ding, Y.; Liu, Z.; Peng, H.; Xu, B. A Review Study on Traction Energy Saving of Rail Transport. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2013, 2013, 156548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, S.; Kondo, K. Recent Energy-Saving Technologies for Railway Traction Systems. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), Nagasaki, Japan, 9–13 November 2024; pp. 1850–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierzejewski, L.; Szeląg, A. Aktualne kierunki ograniczania zużycia energii elektrycznej w transporcie kolejowym. TTS Tech. Transp. Szyn. 2004, 11, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, H.; Roberts, C.; Hillmansen, S.; Schmid, F. An assessment of available measures to reduce traction energy use in railway networks. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 106, 1149–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, F. Analysis of factors affecting traction energy consumption of electric multiple unit trains based on data mining. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Rakha, H.A. Electric train energy consumption modeling. Appl. Energy 2017, 193, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Zhu, H.; Sun, X.; Lin, S. Evaluation of power supply capability and quality for traction power supply system considering the access of distributed generations. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2020, 14, 3644–3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingaitis, L.P.; Vaičiunas, G. The Influence of the Exploitation Conditions of the Rolling Stock on the Effectiveness of Recuperation. Transp. Eng. 2009, 30, 192–198. [Google Scholar]

- Urbaniak, M.; Kardas-Cinal, E.; Jacyna, M. Optimization of Energetic Train Cooperation. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartłomiejczyk, M.; Połom, M. Multiaspect measurement analysis of breaking energy recovery. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 127, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołębiowski, P.; Jacyna, M.; Stańczak, A. The Assessment of Energy Efficiency versus Planning of Rail Freight Traffic: A Case Study on the Example of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinayová, A.; Dömény, I.; Abramović, B.; Šipuš, D. Electrified and non-electrified railway infrastructure—Economic efficiency of rail vehicle change. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 74, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolorz, M. Railway service facilities and services provided to rail carriers in the activity of energy companies. Internet Q. Antitrust Regul. 2019, 8, 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- Szeląg, A.; Massel, A. Application of multi-criteria analysis for the selection of power supply system for electrification new lines in the existing railway network energized by 3 KV DC system. Arch. Transp. 2025, 74, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeląg, A. Zwiększanie efektywności energetycznej transportu szynowego. TTS Tech. Transp. Szyn. 2008, 12, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Energy saving in Rail: Consumption Assessment, Efficiency Improvement and Saving Strategies, Overview Report. Available online: https://rail-research.europa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/ERSIPB-EDSIPB-B-S2R-219-01_-_20240314_Energy_saving_measures_in_rail_report_changes__2_.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Energy Efficiency and CO2 Emissions. Available online: https://uic.org/sustainability/energy-efficiency-and-co2-emissions/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Alfieri, L.; Battistelli, L.; Pagano, M. Energy efficiency strategies for railway application: Alternative solutions applied to a real case study. IET Electr. Syst. Transp. 2017, 8, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak, M.; Jacyna, M. Wybrane zagadnienia wielokryterialnej optymalizacji ruchu kolejowego w aspekcie minimalizacji kosztów. Probl. Kolejnictwa 2015, 169, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kierzkowski, A.; Haładyn, S. Method for Reconfiguring Train Schedules Taking into Account the Global Reduction of Railway Energy Consumption. Energies 2022, 15, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Gao, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Dong, H. Train-Centric Communication Based Autonomous Train Control System. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćwil, M.; Bartnik, W.; Jarzębowski, S. Railway Vehicle Energy Efficiency as a Key Factor in Creating Sustainable Transportation Systems. Energies 2021, 14, 5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitarz, M. The Safety, Operation, and Energy Efficiency of Rail Vehicles—A Case Study for Poland. Energies 2024, 17, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 1302/2014 of 18 November 2014 Concerning a Technical Specification for Interoperability Relating to the Rolling Stock—Locomotives and Passenger Rolling Stock Subsystem of the Rail System in the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02014R1302-20250427 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Van der Spiegel, B.; Mondejar, J.A.R. Energy Metering of Trains: The European Experience. IEEE Electrif. Mag. 2020, 8, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, M.; Jafari Kaleybar, H.; Brenna, M.; Zaninelli, D. Energy Management Systems for Smart Electric Railway Networks: A Methodological Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzior, A.; Staszek, M. Energy Management in the Railway Industry: A Case Study of Rail Freight Carrier in Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 6875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2016/798 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2016 on Railway Safety. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02016L0798-20201023 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 402/2013 of 30 April 2013 on the Common Safety Method for Risk Evaluation and Assessment and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 352/2009. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02013R0402-20150803 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Gołębiowski, P. Ocena Ryzyka w Planowaniu Ruchu Kolejowego z Punktu Widzenia Operatora Przewozów Pasażerskich; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Warszawskiej: Warszawa, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- The Office of Rail Transport. Ekspertyza Dotycząca Praktycznego Stosowania Przez Podmioty Sektora Kolejowego Wymagań Wspólnej Metody Bezpieczeństwa w Zakresie Oceny Ryzyka (CSM RA) Opracowana w Formie Przewodnika. Available online: https://www.utk.gov.pl/download/1/12494/UTKCSMRAfinal2.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Licciardello, R.; Baldassarra, A.; Vitali, P.; Tieri, A.; Cruciani, M.; Vasile, A.N. Limits and opportunities of risk analysis application in railway systems. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2013, 134, 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Andrić, J.M.; Wang, J.; Zhong, R. Identifying the Critical Risks in Railway Projects Based on Fuzzy and Sensitivity Analysis: A Case Study of Belt and Road Projects. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macura, D.; Laketić, M.; Pamučar, D.; Marinković, D. Risk analysis model with interval type-2 fuzzy FMEA–Case study of railway infrastructure projects in the Republic of Serbia. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2022, 19, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.; Lin, W.; Stirling, A. An intelligent railway safety risk assessment support system for railway operation and maintenance analysis. Open Transp. J. 2013, 7, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinmohammadi, F.; Alkali, B.; Shafiee, M.; Bérenguer, C.; Labib, A. Risk evaluation of railway rolling stock failures using FMECA technique: A case study of passenger door system. Urban Rail Transit 2016, 2, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołębiowski, P.; Góra, I.; Bolzhelarskyi, Y. Risk assessment in railway rolling stock planning. Arch. Transp. 2023, 65, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaciłło, L.; Jacyna, M.; Szczepański, E.; Izdebski, M. Risk assessment for rail freight transport operations. Eksploat. I Niezawodn. 2021, 23, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedeliakova, E.; Hudakova, M.; Masar, M.; Lizbetinova, L.; Stasiak-Betlejewska, R.; Šulko, P. Sustainability of Railway Undertaking Services with Lean Philosophy in Risk Management—Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Feng, D.; Sun, X. Traction Power-Supply System Risk Assessment for High-Speed Railways Considering Train Timetable Effects. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2019, 68, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Yu, Q.; Sun, X.; Zhu, H.; Lin, S.; Liang, J. Risk assessment for electrified railway catenary system under comprehensive influence of geographical and meteorological factors. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2021, 7, 3137–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciszewski, T.; Wojciechowski, J.; Kornaszewski, M.; Krawczyk, G.; Kuźmińska-Sołśnia, B.; Hermanowicz, A. Assessment of the Risk of Failure in Electric Power Supply Systems for Railway Traffic Control Devices. Sensors 2025, 25, 4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, D.; Li, M.; Zhang, J. Electromagnetic Compatibility Risk Assessment Model for High-Speed Rail On-Board Signaling System. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2024, 66, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyrgała, D.; Jesień, L.; Kister, Ł.; Koniak, M.; Tolak, Ł. PKP Energetyka po Prywatyzacji—Bezpieczeństwo Dostaw Energii i Przewozów Kolejowych; Collegium Civitas Press: Warszawa, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Matsika, E.; O’Neill, C.; Battista, U.; Khosravi, M.; de Santiago Laporte, A.; Munoz, E. Development of risk assessment specifications for analysing terrorist attacks vulnerability on metro and light rail systems. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 1345–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidis, M.; Hirsch, R.; Majumdar, A. Metro railway safety: An analysis of accident precursors. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 1535–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, L. Railways and Energy; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, P.; Lingegård, S.; Borg, L.; Nyström, J. Procurement of railway infrastructure projects—A European benchmarking study. Civ. Eng. J. 2017, 3, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leśniak, A.; Janowiec, F. Risk Assessment of Additional Works in Railway Construction Investments Using the Bayes Network. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Ali, A.; Eliasson, J. European railway deregulation: An overview of market organization and capacity allocation. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2022, 18, 594–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 31000:2018; Risk Management—Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- IEC 31010:2019; Risk Management—Risk Assessment Techniques. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- PKP Polskie Linie Kolejowe S.A. Network Statement 2024/2025; PKP Polskie Linie Kolejowe S.A.: Warszawa, Poland, 2024.

| No. | Cause (Due to the Fact That …) | Risk (There is a Risk That …) | Effect (Which Will Cause …) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | … there may be a failure of the electric traction vehicle designated to operate a given train, making it impossible for it to continue operating, | … a given train may be operated by a diesel traction vehicle (with the same or lower parameters), | … the costs of operating a given train may be higher, travel comfort may be lower, and delays may occur. |

| 1.2 | … there may be a failure of the electric traction vehicle designated to operate a given train, making it impossible for it to continue operating, | … a given train may be replaced by a replacement bus service, | … travel comfort may be lower, and delays may occur. |

| 1.3 | … there may be a failure of the electric traction unit designated to operate a given train, making it impossible for it to continue operating, | … a given train may be replaced by a replacement train in the form of a traction vehicle (with the same or lower parameters) and carriages, | … the costs of operating a given train may be higher, travel comfort may be lower, and delays may occur. |

| 1.4 | … there may be a failure of the electric traction vehicle designated to operate a given train, making it impossible for it to continue operating, | … a given train may be canceled, | … claims for compensation may arise for failure to provide transport services at the appropriate level. |

| 1.5 | … the rolling stock may be outdated, | … energy consumption by electric traction vehicles may be higher than for modern rolling stock, | … electricity consumption costs may be higher. |

| 1.6 | … there may be a failure of components of the electric traction vehicle designated to operate a given train, | … the comfort of travel on a train composed of a given electric traction unit or driven by an electric traction vehicle in the carriages hauled by it may experience reduced comfort, | … claims for compensation may arise for failure to provide transport services at the appropriate level. |

| 1.7 | … traction vehicles are operated in an uneconomical manner, | … the energy consumption of electric traction vehicles may be higher than when eco-driving principles are applied, | … electricity consumption costs may be higher. |

| No. | Cause (Due to the Fact That …) | Risk (There is a Risk That …) | Effect (Which Will Cause …) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 | … failure of the catenary system at an operating control post or on the open line may occur, | … the train will have to wait for the restoration of traffic, which will cause a long delay or may result in damage to the traction vehicle, making it impossible to continue the journey, | … the railway operator may incur losses and claims for compensation may arise for failure to provide the transport service at the appropriate level. |

| 2.2 | … a power supply failure may occur at an operating control post or on the open line, | … the train will have to wait for the restoration of traffic, which will cause a long delay or may result in damage to the traction vehicle, making it impossible to continue the journey, | … the railway operator may incur losses and claims for compensation may arise for failure to provide the transport service at the appropriate level. |

| 2.3 | … there may be a power outage in the catenary system at an operating control post or on the open line, | … the train will have to wait for the restoration of traffic, which will cause a long delay or may result in damage to the traction vehicle, making it impossible to continue the journey, | … the railway operator may incur losses and claims for compensation may arise for failure to provide the transport service at the appropriate level. |

| 2.4 | … there may be an overload of the power supply system at an operating control post or on the open line, | … the train will have to wait for the restoration of traffic, which will cause a long delay or may result in damage to the traction vehicle, making it impossible to continue the journey, | … the railway operator may incur losses and claims for compensation may arise for failure to provide the transport service at the appropriate level. |

| 2.5 | … traction vehicles may not be equipped with on-board energy recovery devices, | … the ability to recover energy during braking and starting may be limited, | … the profits from the recuperation process (reduction in energy consumption) may not be that high. |

| 2.6 | … the infrastructure manager may have delays in the implementation of the railway electrification process, | … it will be necessary to continue using diesel traction vehicles instead of electric traction vehicles, | … the costs of operating a given train may be higher, and the purchased electric vehicles may not be used efficiently. |

| No. | Cause (Due to the Fact That …) | Risk (There is a Risk That …) | Effect (Which Will Cause …) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 | … there will be an electrical failure in the technical facilities (damage to the catenary system, power supply failure, etc.), | … trains departing from their originating stations will be delayed (known as “start-up delay”), | … the railway operator may incur losses (including the need to pay compensation for the delay caused) and claims for compensation may arise for failure to provide the transport service at the appropriate level. |

| 3.2 | … there will be an electrical failure in the technical facilities (damage to the catenary system, power supply failure, etc.), | … vehicles may not be properly prepared for departure (i.e., unable to complete the required technological process), | … the railway operator may incur losses (including the need to pay compensation for the delay caused) and claims for compensation may arise for failure to provide the transport service at the appropriate level. |

| 3.3 | … the technical facilities use equipment that is highly energy-intensive, | … energy consumption may be higher than that of modern devices, | … electricity consumption costs may be higher. |

| 3.4 | … in the technical facilities, devices are used in a manner characterized by high energy consumption, | … energy consumption may be higher than that of modern devices, | … electricity consumption costs may be higher. |

| 3.5 | … the technical facilities will run out of components for repairing traction vehicles, | … in the case of a breakdown of a traction vehicle that was planned to operate a train, it may not be possible to repair it, | … the costs of operating a given train may be higher, travel comfort may be lower, and delays may occur. |

| 3.6 | … there will be an electrical failure in the technical facilities (damage to the catenary system, power supply failure, etc.), | … there may not be enough space on the sidings for the next train/trains, | … the railway operator may incur losses (including the need to pay compensation for the delay caused) and claims for compensation may arise for failure to provide the transport service at the appropriate level. |

| No. | Cause (Due to the Fact That …) | Risk (There is a Risk That …) | Effect (Which Will Cause …) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.1 | … there may be a lack of traction vehicles with the appropriate parameters (adequate to the parameters declared in the timetable) to operate a given train, | … a traction vehicle may be assigned to operate a given train whose parameters are not appropriate in relation to the parameters specified in the timetable, | … the railway operator may incur losses (including the need to pay compensation for the delay caused) and claims for compensation may arise for failure to provide the transport service at the appropriate level. |

| 4.2 | … the train timetable may be arranged in an unreasonable manner from the point of view of energy recovery, | … the ability to recover energy during braking and starting may be limited, | … the benefits of the recuperation process (reduction in energy consumption) may not be as high as expected. |

| 4.3 | … the train timetable may be arranged in an unreasonable manner, and the train driver will have to use reduced travel times in order to maintain the train’s punctuality, | … energy consumption by electric traction vehicles may be higher than when normal driving times are used (where eco-driving principles can be applied), | … electricity consumption costs may be higher. |

| 4.4 | … an electric traction vehicle may suffer a breakdown at an operating control post or on the open line, which may prevent it from continuing its journey, | … other trains may be suspended or restricted, and delays will occur, | … the railway operator may incur losses (including the need to pay compensation for the delay caused) and claims for compensation may arise for failure to provide the transport service at the appropriate level. |

| 4.5 | … there may be a breakdown on the train’s main route, which may result in it being diverted to an alternative route, | … finding a reasonable detour route may be difficult due to the limitations of electric traction vehicles, | … the railway operator may incur losses and claims for compensation may arise for failure to provide the transport service at the appropriate level. |

| 4.6 | … electric traction vehicles may not be equipped with systems supporting rational driving (eco-driving support systems). | … energy consumption by electric traction vehicles may be higher than when eco-driving principles are applied, | … electricity consumption costs may be higher. |

| No. | Cause (Due to the Fact That …) | Risk (There is a Risk That …) | Effect (Which Will Cause …) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5.1 | … the economic situation in a given country and worldwide is uncertain, | … there may be an increase in the price of energy used for traction purposes, | … electricity consumption costs may be higher. |

| 5.2 | … the economic situation in a given country and worldwide is uncertain, | … there may be an increase in the price of energy used for non-traction purposes, | … electricity consumption costs may be higher. |

| 5.3 | … the economic situation in a given country and worldwide is uncertain, | … during the signing of the contract for electricity supply, the cost per kilowatt-hour or the duration of the fixed-rate contract may be overestimated, | … electricity consumption costs may be higher. |

| 5.4 | … there may be delays in the implementation of investments related to electrification, | … at the time of concluding the contract, the energy supplier’s offer may not be as attractive as it would be at the time of the planned implementation of the investment, | … electricity consumption costs may be higher. |

| No. | Cause (Due to the Fact That …) | Risk (There is a Risk That …) | Effect (Which Will Cause …) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6.1 | … the economic situation in a given country and worldwide is uncertain, | … an energy crisis may occur, | … electricity consumption costs may be higher, or there may be a shortage of electricity for traction and non-traction purposes. |

| 6.2 | … difficult weather conditions may occur, | … there may be disruptions in the supply of electricity for traction and non-traction purposes, | … the railway operator may incur losses and claims for compensation may arise for failure to provide the transport service at the appropriate level. |

| 6.3 | … there may be delays in the implementation of investments related to electrification, | … electric traction vehicles that were purchased for investment purposes at the right time may not be operated effectively, | … the railway operator may incur losses. |

| 6.4 | … a cyberattack on the power supply system may occur, | … there may be disruptions in the supply of electricity for traction and non-traction purposes, | … the railway operator may incur losses and claims for compensation may arise for failure to provide the transport service at the appropriate level. |

| No. | National Variables Describing the Impact | Proposed Probability Distribution for the National Variable |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | 1. Total costs of the railway undertaking’s operations 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 1. Triangular distribution (min. 10.685 billion PLN/year, mid. 11.994 billion PLN/year, max. 13.3 billion PLN/year) 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 1.2 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 1.3 | 1. Total costs of the railway undertaking’s operations 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 1. Triangular distribution (min. 10.685 billion PLN/year, mid. 11.994 billion PLN/year, max. 13.3 billion PLN/year) 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 1.4 | 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 1.5 | 4. Costs related to electricity consumption by trains | 4. Triangular distribution (min. 1.947 billion PLN/year, mid. 2.05 billion PLN/year, max. 2.152 billion PLN/year) |

| 1.6 | 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 1.7 | 4. Costs related to electricity consumption by trains | 4. Triangular distribution (min. 1.947 billion PLN/year, mid. 2.05 billion PLN/year, max. 2.152 billion PLN/year) |

| No. | National Variables Describing the Impact | Proposed Probability Distribution for the National Variable |

|---|---|---|

| 2.1 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 2.2 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings, 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 2.3 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 2.4 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 2.5 | 5. Profits related to the use of recuperation in the railway system | 5. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 51.247 million PLN/year, max. 102.493 million PLN/year) |

| 2.6 | 1. Total costs of the railway undertaking’s operations | 1. Triangular distribution (min. 10.685 billion PLN/year, mid. 11.994 billion PLN/year, max. 13.3 billion PLN/year) |

| No. | National Variables Describing the Impact | Proposed Probability Distribution for the National Variable |

|---|---|---|

| 3.1 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 3.2 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 3.3 | 4. Costs related to electricity consumption by trains | 4. Triangular distribution (min. 1.947 billion PLN/year, mid. 2.05 billion PLN/year, max. 2.152 billion PLN/year) |

| 3.4 | 4. Costs related to electricity consumption by trains | 4. Triangular distribution (min. 1.947 billion PLN/year, mid. 2.05 billion PLN/year, max. 2.152 billion PLN/year) |

| 3.5 | 1. Total costs of the railway undertaking’s operations 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 1. Triangular distribution (min. 10.685 billion PLN/year, mid. 11.994 billion PLN/year, max. 13.3 billion PLN/year) 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 3.6 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| No. | National Variables Describing the Impact | Proposed Probability Distribution for the National Variable |

|---|---|---|

| 4.1 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 4.2 | 5. Profits related to the use of recuperation in the railway system | 5. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 51.247 million PLN/year, max. 102.493 million PLN/year) |

| 4.3 | 4. Costs related to electricity consumption by trains | 4. Triangular distribution (min. 1.947 billion PLN/year, mid. 2.05 billion PLN/year, max. 2.152 billion PLN/year) |

| 4.4 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 4.5 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings, 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 4.6 | 4. Costs related to electricity consumption by trains | 4. Triangular distribution (min. 1.947 billion PLN/year, mid. 2.05 billion PLN/year, max. 2.152 billion PLN/year) |

| No. | National Variables Describing the Impact | Proposed Probability Distribution for the National Variable |

|---|---|---|

| 5.1 | 4. Costs related to electricity consumption by trains | 4. Triangular distribution (min. 1.947 billion PLN/year, mid. 2.05 billion PLN/year, max. 2.152 billion PLN/year) |

| 5.2 | 4. Costs related to electricity consumption by trains | 4. Triangular distribution (min. 1.947 billion PLN/year, mid. 2.05 billion PLN/year, max. 2.152 billion PLN/year) |

| 5.3 | 4. Costs related to electricity consumption by trains | 4. Triangular distribution (min. 1.947 billion PLN/year, mid. 2.05 billion PLN/year, max. 2.152 billion PLN/year) |

| 5.4 | 4. Costs related to electricity consumption by trains | 4. Triangular distribution (min. 1.947 billion PLN/year, mid. 2.05 billion PLN/year, max. 2.152 billion PLN/year) |

| No. | National Variables Describing the Impact | Proposed Probability Distribution for the National Variable |

|---|---|---|

| 6.1 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 4. Costs related to electricity consumption by trains | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 4. Triangular distribution (min. 1.947 billion PLN/year, mid. 2.05 billion PLN/year, max. 2.152 billion PLN/year) |

| 6.2 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| 6.3 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) |

| 6.4 | 2. Costs related to delays generated by trains of individual undertakings 3. Costs related to the deterioration of travel comfort | 2. Triangular distribution (min. 0 PLN/year, mid. 4.361 million PLN/year, max. 8.722 million PLN/year) 3. Triangular distribution (min. 145.962 million PLN/year, mid. 164.692 million PLN/year, max. 183.692 million PLN/year) |

| Risk Group Number . Risk Number . National Variable Number | Minimum Value (min.) [PLN/Year] | Most Likely Value (mid.) [PLN/Year] | Maximum Value (max.) [PLN/Year] | Average Value from Simulations [PLN/Year] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1.1. | 10,685,008,800.00 | 11,993,696,190.00 | 13,299,732,000.00 | 12,754,027,565.11 |

| 1.1.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 5,294,083.96 |

| 1.1.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 156,910,100.89 |

| 1.2.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 4,384,216.34 |

| 1.2.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 158,435,008.03 |

| 1.3.1. | 10,685,008,800.00 | 11,993,696,190.00 | 13,299,732,000.00 | 11,271,672,501.52 |

| 1.3.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 6,711,083.36 |

| 1.3.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 177,371,883.35 |

| 1.4.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 168,033,663.16 |

| 1.5.4. | 1,947,373,273.07 | 2,049,866,603.23 | 2,152,359,933.39 | 2,095,937,737.06 |

| 1.6.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 155,027,041.79 |

| 1.7.4. | 1,947,373,273.07 | 2,049,866,603.23 | 2,152,359,933.39 | 2,044,904,390.70 |

| Risk group—1 | 12,778,074,073.07 | 14,212,615,984.28 | 15,644,776,315.49 | 15,051,444,322.78 |

| Risk Group Number . Risk Number . National Variable Number | Minimum Value (min.) [PLN/Year] | Most Likely Value (mid.) [PLN/Year] | Maximum Value (max.) [PLN/Year] | Average Value from Simulations [PLN/Year] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 4,863,742.29 |

| 2.1.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 165,675,056.00 |

| 2.2.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 3,401,450.80 |

| 2.2.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 176,607,390.83 |

| 2.3.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 4,212,490.01 |

| 2.3.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 162,730,853.82 |

| 2.4.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 2,410,415.05 |

| 2.4.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 169,990,302.44 |

| 2.5.5. | 0.00 | 51,246,665.08 | 102,493,330.16 | 67,093,905.00 |

| 2.6.1. | 10,685,008,800.00 | 11,993,696,190.00 | 13,299,732,000.00 | 11,783,719,602.12 |

| Risk group—2 | 10,830,700,800.00 | 12,111,502,715.97 | 13,389,923,051.94 | 11,087,241,757.12 |

| Risk Group Number . Risk Number . National Variable Number | Minimum Value (min.) [PLN/Year] | Most Likely Value (mid.) [PLN/Year] | Maximum Value (max.) [PLN/Year] | Average Value from Simulations [PLN/Year] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 3,220,052.16 |

| 3.1.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 161,998,956.70 |

| 3.2.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 6,060,499.47 |

| 3.2.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 173,684,769.80 |

| 3.3.4. | 1,947,373,273.07 | 2,049,866,603.23 | 2,152,359,933.39 | 1,988,694,965.09 |

| 3.4.4. | 1,947,373,273.07 | 2,049,866,603.23 | 2,152,359,933.39 | 2,092,210,189.52 |

| 3.5.1. | 10,685,008,800.00 | 11,993,696,190.00 | 13,299,732,000.00 | 11,937,436,259.70 |

| 3.5.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 6,526,673.67 |

| 3.5.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 155,845,021.41 |

| 3.6.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 6,256,345.24 |

| 3.6.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 159,664,422.96 |

| Risk group–3 | 12,778,074,073.07 | 14,212,615,984.28 | 15,644,776,315.49 | 14,305,275,475.01 |

| Risk Group Number . Risk Number . National Variable Number | Minimum Value (min.) [PLN/Year] | Most Likely Value (mid.) [PLN/Year] | Maximum Value (max.) [PLN/Year] | Average Value from Simulations [PLN/Year] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.1.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 2,508,032.81 |

| 4.1.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 177,926,109.55 |

| 4.2.5. | 0.00 | 51,246,665.08 | 102,493,330.16 | 34,555,267.81 |

| 4.3.4. | 1,947,373,273.07 | 2,049,866,603.23 | 2,152,359,933.39 | 2,030,178,953.20 |

| 4.4.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 3,604,481.12 |

| 4.4.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 167,936,958.13 |

| 4.5.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 1,565,172.48 |

| 4.5.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 165,310,903.05 |

| 4.6.4. | 1,947,373,273.07 | 2,049,866,603.23 | 2,152,359,933.39 | 2,016,096,148.71 |

| Risk group–4 | 2,093,065,273.07 | 2,167,673,129.20 | 2,242,550,985.33 | 2,132,448,983.80 |

| Risk Group Number . Risk Number . National Variable Number | Minimum Value (min.) [PLN/Year] | Most Likely Value (mid.) [PLN/Year] | Maximum Value (max.) [PLN/Year] | Average Value from Simulations [PLN/Year] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.1.4. | 1,947,373,273.07 | 2,049,866,603.23 | 2,152,359,933.39 | 2,090,071,481.34 |

| 5.2.4. | 1,947,373,273.07 | 2,049,866,603.23 | 2,152,359,933.39 | 2,067,092,614.67 |

| 5.3.4. | 1,947,373,273.07 | 2,049,866,603.23 | 2,152,359,933.39 | 2,026,191,998.88 |

| 5.4.4. | 1,947,373,273.07 | 2,049,866,603.23 | 2,152,359,933.39 | 2,009,787,568.26 |

| Risk group–5 | 1,947,373,273.07 | 2,049,866,603.23 | 2,152,359,933.39 | 2,021,485,777.50 |

| Risk Group Number . Risk Number . National Variable Number | Minimum Value (min.) [PLN/Year] | Most Likely Value (mid.) [PLN/Year] | Maximum Value (max.) [PLN/Year] | Average Value from Simulations [PLN/Year] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.1.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 2,940,432.09 |

| 6.1.4. | 1,947,373,273.07 | 2,049,866,603.23 | 2,152,359,933.39 | 2,041,056,092.87 |

| 6.2.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 4,491,885.65 |

| 6.2.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 176,894,384.56 |

| 6.3.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 3,044,180.17 |

| 6.4.2. | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 5,179,572.13 |

| 6.4.3. | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 158,200,943.84 |

| Risk group–6 | 2,093,065,273.07 | 2,218,919,794.28 | 2,345,044,315.49 | 2,232,111,020.70 |

| National Variable Number | Minimum Value (min.) [PLN/Year] | Most Likely Value (mid.) [PLN/Year] | Maximum Value (max.) [PLN/Year] | Average Value from Simulations [PLN/Year] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10,685,008,800.00 | 11,993,696,190.00 | 13,299,732,000.00 | 12,942,881,246.52 |

| 2 | 0.00 | 4,361,191.05 | 8,722,382.10 | 4,790,567.93 |

| 3 | 145,692,000.00 | 164,692,000.00 | 183,962,000.00 | 158,907,277.82 |

| 4 | 1,947,373,273.07 | 2,049,866,603.23 | 2,152,359,933.39 | 2,092,922,820.64 |

| 5 | 0.00 | 51,246,665.08 | 102,493,330.16 | 75,157,549.91 |

| SUM | 12,778,074,073.07 | 14,161,369,319.20 | 15,542,282,985.33 | 14,160,588,863.66 |

| Percentile | Average Value from Simulations [PLN/Year] | Risk Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| 0% | 12,824,545,257.32 | 0 |

| 5% | 13,215,290,603.91 | 660,764,530.20 |

| 10% | 13,396,394,651.63 | 1,339,639,465.16 |

| 15% | 13,534,635,328.14 | 2,030,195,299.22 |

| 20% | 13,652,148,928.74 | 2,730,429,785.75 |

| 25% | 13,753,968,835.22 | 3,438,492,208.81 |

| 30% | 13,848,281,414.13 | 4,154,484,424.24 |

| 35% | 13,933,447,954.09 | 4,876,706,783.93 |

| 40% | 14,014,719,732.62 | 5,605,887,893.05 |

| 45% | 14,089,062,241.14 | 6,340,078,008.51 |

| 50% | 14,159,617,595.70 | 7,079,808,797.85 |

| 55% | 14,231,547,832.91 | 7,827,351,308.10 |

| 60% | 14,306,509,951.27 | 8,583,905,970.76 |

| 65% | 14,385,484,729.83 | 9,350,565,074.39 |

| 70% | 14,471,278,992.10 | 10,129,895,294.47 |

| 75% | 14,565,342,459.21 | 10,924,006,844.41 |

| 80% | 14,666,486,971.05 | 11,733,189,576.84 |

| 85% | 14,784,178,027.18 | 12,566,551,323.10 |

| 90% | 14,921,596,434.06 | 13,429,436,790.65 |

| 95% | 15,104,087,538.89 | 14,348,883,161.95 |

| 100% | 15,489,979,662.42 | 15,489,979,662.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gołębiowski, P.; Kukulski, J.; Góra, I.; Bolzhelarskyi, Y. A Monte Carlo Based Method for Assessing Energy-Related Operational Risks in Railway Undertakings. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010051

Gołębiowski P, Kukulski J, Góra I, Bolzhelarskyi Y. A Monte Carlo Based Method for Assessing Energy-Related Operational Risks in Railway Undertakings. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleGołębiowski, Piotr, Jacek Kukulski, Ignacy Góra, and Yaroslav Bolzhelarskyi. 2026. "A Monte Carlo Based Method for Assessing Energy-Related Operational Risks in Railway Undertakings" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010051

APA StyleGołębiowski, P., Kukulski, J., Góra, I., & Bolzhelarskyi, Y. (2026). A Monte Carlo Based Method for Assessing Energy-Related Operational Risks in Railway Undertakings. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010051