Oleanolic Acid and Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanistic Hypothesis of Therapeutic Potential

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Whenever a theory appears to you as the only possible one, take this as a sign that you have neither understood the theory nor the problem which it was intended to solve.”

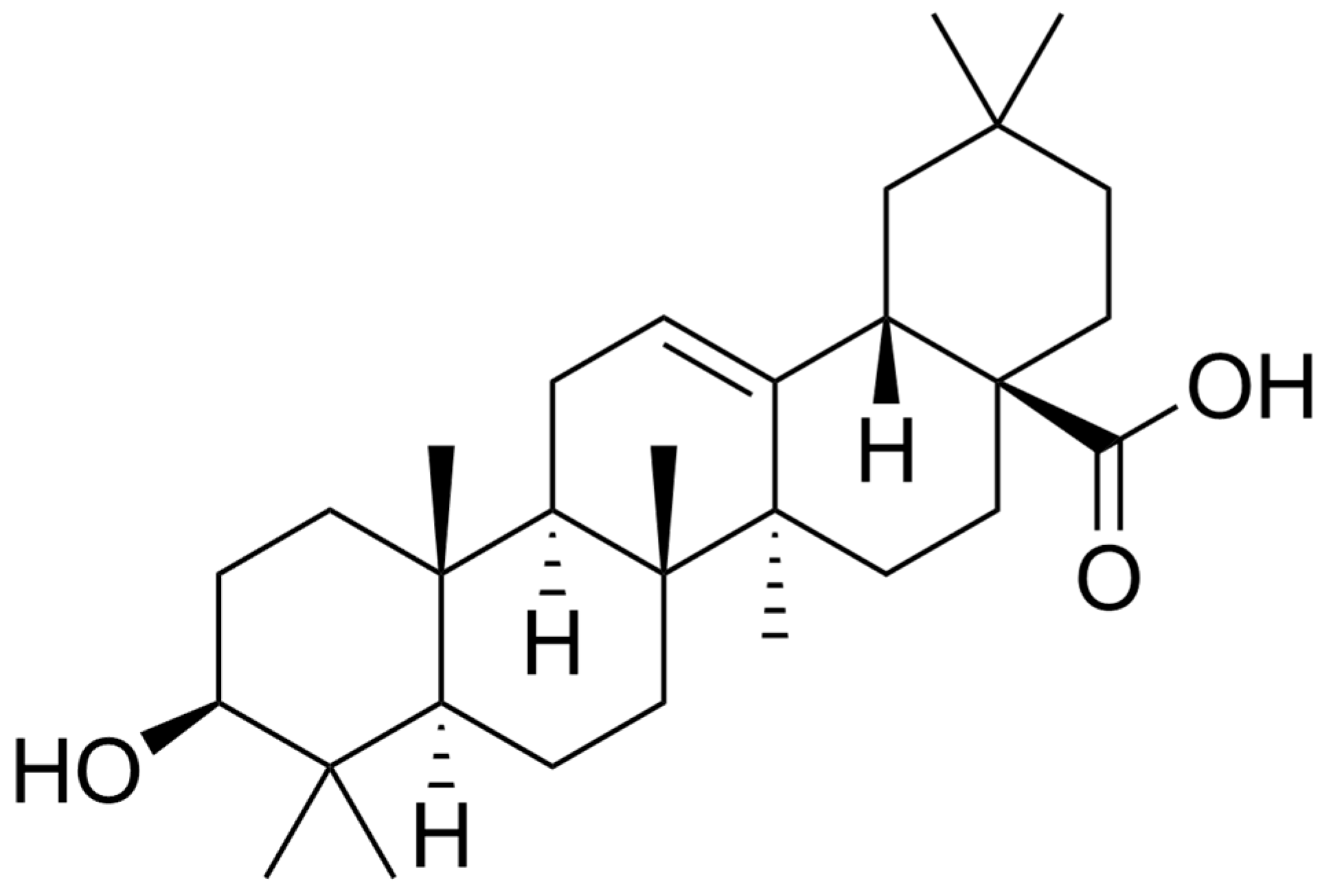

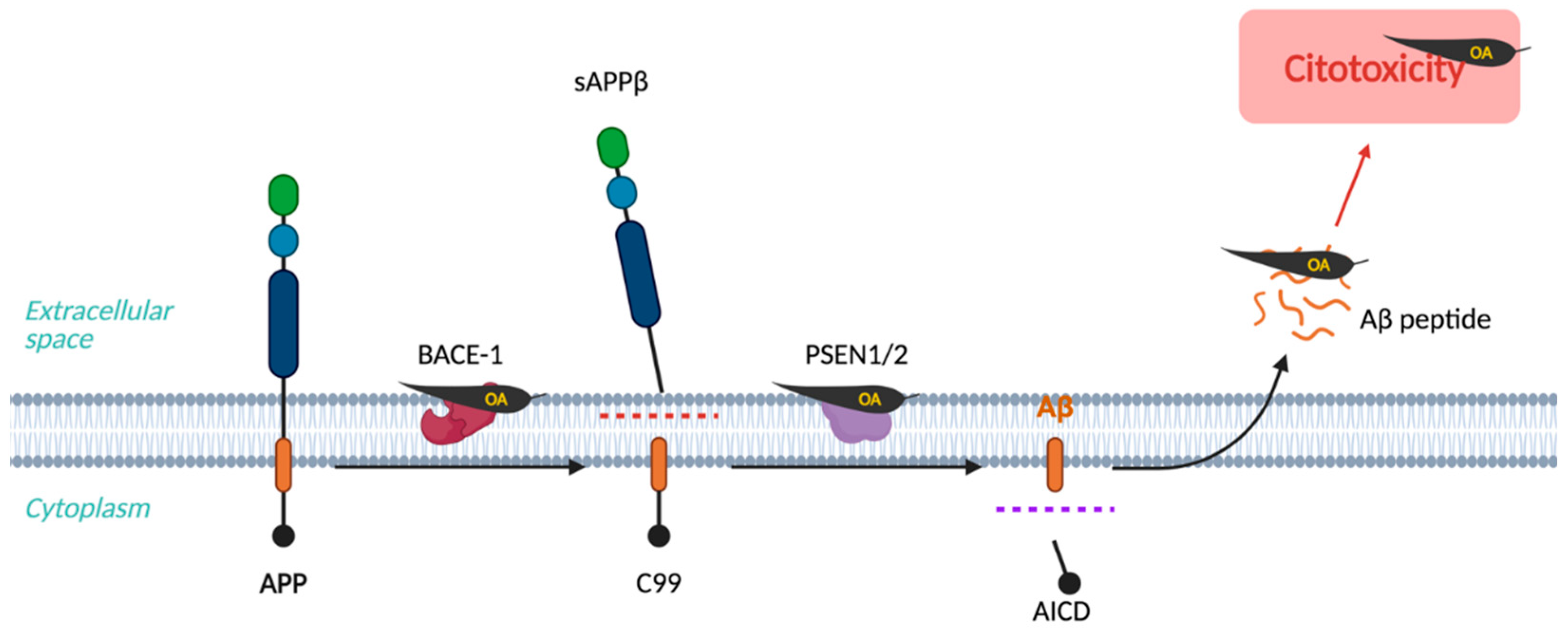

2. Amyloid Hypothesis

3. Tau Hypothesis

4. Cholinergic Hypothesis

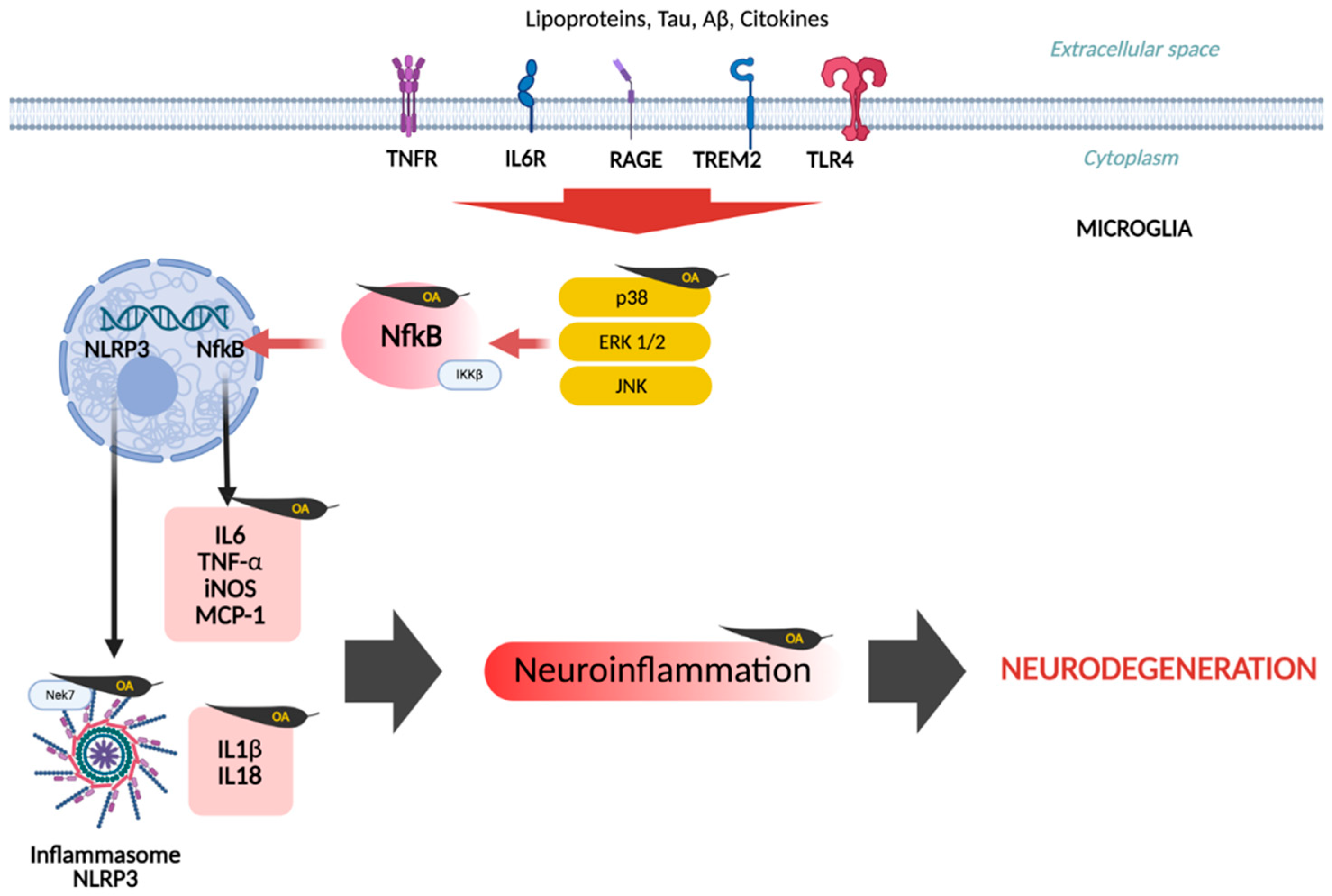

5. Neuroinflammatory Hypothesis

| Compound | Key Findings | Experimental Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDDO | Suppression of iNOS, COX2. | Microglia primary culture | [93] |

| Intraperitoneal injection 50 mg/kg/dayOA and Ery | Lower leukocyte recruitment, improved BBB integrity, attenuated TNF-α production; downregulated COX-2 and iNOS expression. | C57BL/J6 female mice, BV2 microglial cells (LPS or IFN-γ stimulation) | [94] |

| OA 0.5–10.0 μM | Dose-dependent reduction in IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β expression; reduced iNOS and NO synthesis. | BV2 cells (LPS stimulation) | [95] |

| 10, 20, 40 mg/kg (In vivo) 10, 20, 40 μM (In vitro) | Alleviated pain. Shifted microglia from M1 to M2. Inhibition of HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB | SNL-induced neuropathic pain mice & BV2 cells (LPS-stimulation) | [96] |

| OA (1, 10, 20, 30, 40 μM) | Improved neuronal viability; reduced IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β; inhibited sPLA2-IIA and intracellular Ca2+ fluxes. | DI-TNC1 astrocytes & SH-SY5Y neurons (Co-culture) | [97] |

| Malva parviflora extract (OA & Scopoletin) | Reduced astrogliosis, insoluble Aβ, and spatial learning deficits; improved phagocytosis, reduced microglial activation. | 5XFAD transgenic mice (AD model), microglia primary culture | [98] |

| 100 nM CDDO-Me | Reduced microglial activation and pro-inflammatory genes; enhanced phagocytosis and inhibited ROS. | BV2 cells, primary microglia, macrophages, and neurons | [33] |

| CDDO-MA (800 mg/kg) | Improved cognitive abilities; reduced neuroinflammatory and oxidative stress toxicity (no change in Aβ levels). | Tg19959 transgenic mice (AD model) | [31] |

| OA and N-substituted OA derivatives | Reduced TNF-α, IL-6, IL-17, IBA1, and iNOS expression; inhibited NF-κB signaling pathway. | THP-1 monocytes and RAW 264.7 macrophages | [23] |

| OA (5, 10, and 20 mg/kg) | Ameliorated motor deficits and depressive behaviors by reducing synuclein/neuroinflammation, restoring neurotransmitter levels, and activating the Nrf2-BDNF-Dopaminergic signaling pathways. | Male Swiss Albino mice (Rotenone-induced Parkinsonism + Chronic Unpredictable Stress). | [100] |

| OA (3, 10, and 30 mg/kg) | Antidepressant-like effects by reducing immobility time, increasing hippocampal BDNF levels, and reducing neuroinflammation (TNF-α and IL-6). | Female and male Swiss mice (Depression-like behavior induced by Maternal Separation). | [101] |

| Quinoa Saponins (OA-glucopyranosides) | Attenuated anxiety and depression-like behaviors by inhibiting the TLR4/NFkB pathway, reducing neuroinflammation, restoring the intestinal barrier, and modulating gut microbiota (increasing Lactobacillus). | Male C57BL/6J mice (LPS stimulation). | [104] |

| CDDO-TFEA 100 nM | Attenuated EAE clinical severity by suppressing Th1/Th17 cytokines (IL-17, IFN-γ), activating the Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant pathway, and promoting remyelination and oligodendrocyte preservation. | Female C57BL/6 mice (Experimental Induced Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis). | [103] |

| CDDO-Me 10 μM | Inhibited microglial activation and monocyte infiltration by suppressing NFkB and p38 MAPK phosphorylation; exerted neuroprotective effects by reducing vasogenic edema and neuronal death. | Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Status Epilepticus induced by Pilocarpine). | [105] |

| OA-Acetate. 10 mg/kg, 30 mg/kg | Attenuated EAE symptoms by inhibiting TLR2 signaling, reducing Th1/Th17 differentiation, and decreasing the expression of adhesion molecules and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ IL-17). | Female C57BL/6 mice (Experimental Induced Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis) | [102] |

| CDDO-EA and CDDO-TFEA. (400 or 800 mg/kg) | Significantly extended survival and delayed onset of motor symptoms; reduced oxidative stress, inhibited microglial/astrocytic activation, and strongly induced Nrf2/ARE target genes in the spinal cord. | G93A-SOD1 Transgenic Mice (Model for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis), NSC-34 Cell Culture | [106] |

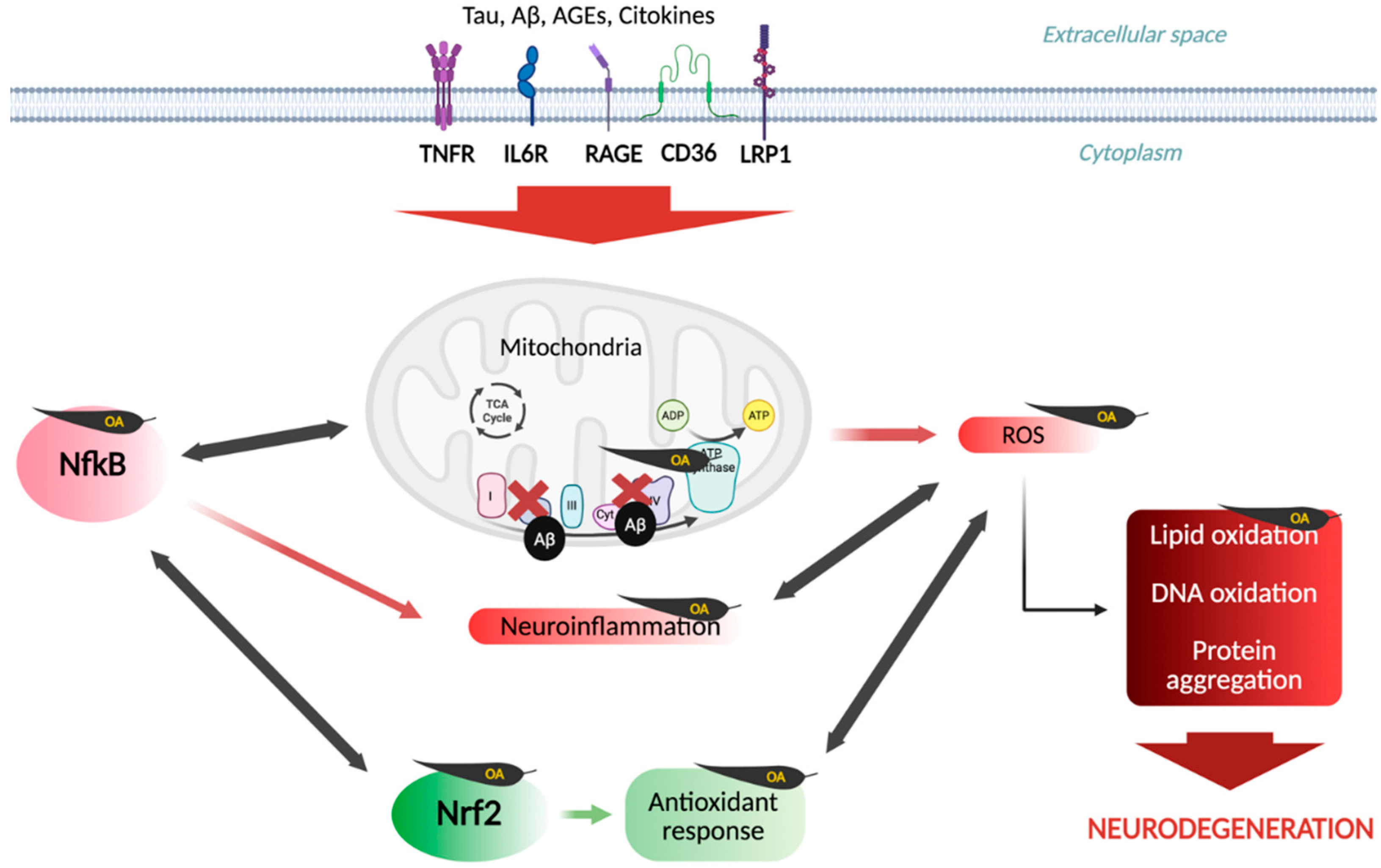

6. Oxidative Stress Hypothesis

| Compound | Key Findings | Experimental Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| OA, 10 μM, 15 μM, 25 μM | Increased STC-1 and UCP2 protein synthesis; reduced ROS, apoptosis, and Caspase-3 activity. | N2a/APP695swe cells (AD in vitro model) | [121] |

| S. chrysophylla extract (OA) | Strong scavenging activity and significant reduction in lipid peroxidation. | DPPH radical scavenging, lipid peroxidation (LPO) inhibition | [61] |

| Dipsacus asperoides saponins 1–300 mg/L | Preserved LDH activity; dose-dependent reduction in MDA concentrations. | Primary cortical and hippocampal neurons (Aβ treated) | [123] |

| CDDO-MA. 800 mg/kg in diet | Reduced carbonylated proteins; increased HO-1 expression. | Tg19959 transgenic mice (overexpressing human APP) | [31] |

| OA 10 μM | Reduced mitochondrial ROS in BV2 cells. Reestablished GSH levels. | BV2 microglial cells; Chemical radical assays | [95] |

| OA 0.5–10 μM | Limited direct radical scavenging. | ABTS/DPPH/ORAC/Rancimat | [119] |

| OA. 5–320 μM | OA demonstrated potent antioxidant activity (comparable to ascorbic acid at 320 μM). | DPPH, ABTS, and LPO inhibition | [29] |

| OA; CDDO-TFEA; CDDO-EA; CDDO-2P-Im | Potent induction of Phase II responses multitarget neuroprotectors by activating the Nrf2/ARE pathway and inhibiting NF-κB. | Maternal separation (mice), EAE (MS model), ALS (G93A mice), SAH (rat/mouse), AD (APP/PS1 mice). | [101,103,120,126,127,128] |

7. Metabolic Hypothesis

Crosstalk Mechanisms

| Compound | Key Findings | Experimental Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| OA 5, 10, 20 mg/kg from Cornus officinalis | Lower plasma glucose by stimulating acetylcholine (ACh) release that activates muscarinic M3 receptors on pancreatic beta-cells, leading to an increase in insulin secretion | Normal and STZ-induced diabetic Wistar rats; Isolated pancreatic islets | [81] |

| OA. 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg | Significant neuroprotection by modulating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and STAT-3/GSK-3β | Wistar rats. Neurotoxicity induced by Methylmercury | [150] |

| Pyrazole-fused OA | Potent selective alpha-glucosidase inhibition. IC50 = 2.64 ± 0.13 μM | In vitro assay. In silico: Molecular docking and SAR analysis | [149] |

| Indole-OA and methyl ester derivatives | Selective alpha-glucosidase inhibition Indole OA derivatives 4.02–5.30 μM, OA methyl ester derivatives 10 μM and 5.52 µM | In vitro: alpha-glucosidase inhibition assays; Kinetics: Lineweaver-Burk plots | [148] |

| OA (5, 10, and 20 mg/kg) | Activated the Nrf2-BDNF-Dopaminergic signaling pathways. | Male Swiss Albino mice (Rotenone-induced Parkinsonism + Chronic Unpredictable Stress). | [100] |

| CDDO-EA and CDDO-TFEA (400 or 800 mg/kg) | Reduced oxidative stress, strongly induced Nrf2/ARE target genes in the spinal cord. | G93A-SOD1 Transgenic Mice (Model for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis), NSC-34 Cell Culture | [106] |

| CDDO-Im 0.5 mg/kg | Improved neurological function by activating the Nrf2/ARE pathway. | Rat model of Post-Stroke Depression induced by Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion | [185] |

| 10 μM OA in TRLs | Inclusion of lipophilic bioactives in TRLs reduces microglial inflammatory response and ROS/NO synthesis. | BV2 microglial cells treated with synthetic TRLs | [169] |

| OA 80 mg/kg | Enhanced insulin signaling pathway by increasing the expression of insulin receptor and GLUT4 | STZ-induced diabetic male rats (Type 1 Diabetes model) | [186] |

| OA (10–200 μΜ) | Upregulation of AMPK and its downstream targets (TSC2, ULK1) while inhibition of mTOR | Colon Cancer (CC) cells (HCT116, SW480) | [189] |

8. Bioavailability

9. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| ACh | Acetylcholine |

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AMPK | Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase |

| APP | Amyloid precursor protein |

| BACE1 | Beta-secretase 1 |

| BChE | Butyrylcholinesterase |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CaMKII | Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II |

| CAT | Choline acetyltransferase |

| CDDO | 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic acid |

| CDDO-Im | CDDO Imidazoline |

| CDDO-MA | CDDO-methylamide |

| CDDO-Me | CDDO Methyl-ester |

| CDDO-TFEA | CDDO trifluoroethylamide |

| CDK5 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 |

| GSK-3β | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta |

| IDE | Insulin-degrading enzyme |

| IL1β | Interleukin-1beta |

| IL6 | Interleukin-6 |

| KEAP1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| LTD | Long-term depression |

| LTP | Long-term potentiation |

| MTBR-Tau243 | Microtubule-binding region Tau containing residue 243 |

| NbM | Nucleus basalis of Meynert |

| NFT | Neurofibrillary tangle |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B |

| NMDAR2B | N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit 2B |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| OA | oleanolic acid |

| PI3K/Akt | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Protein kinase B |

| PKC | Protein kinase C |

| PSEN1/PSEN2 | Presenilin 1/Presenilin 2 |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| STC-1 | Stanniocalcin-1 |

| Tau | Microtubule-associated protein Tau |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TrkB | Tropomyosin receptor kinase B |

| TRL | Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins |

| UA | Ursolic acid |

| UCP-2 | Uncoupling protein-2 |

| UPR | Unfolded protein response |

References

- Ferrari, C.; Sorbi, S. the Complexity of Alzheimer’S Disease: An Evolving Puzzle. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 1047–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2025 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 11, 332–384. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, C.E.; Kulminski, A.M. The Alzheimer’s Disease Exposome. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019, 15, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avgerinos, K.I.; Manolopoulos, A.; Ferrucci, L.; Kapogiannis, D. Critical assessment of anti-amyloid-β monoclonal antibodies effects in Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis highlighting target engagement and clinical meaningfulness. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bulck, M.; Sierra-Magro, A.; Alarcon-Gil, J.; Perez-Castillo, A.; Morales-Garcia, J.A. Novel approaches for the treatment of alzheimer’s and parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellano, J.M.; Ramos-Romero, S.; Perona, J.S. Oleanolic Acid: Extraction, Characterization and Biological Activity. Nutrients 2022, 14, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Aparicio, Á.; Correa-Rodríguez, M.; Castellano, J.M.; Schmidt-RioValle, J.; Perona, J.S.; González-Jiménez, E. Potential Molecular Targets of Oleanolic Acid in Insulin Resistance and Underlying Oxidative Stress: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkoe, D.J.; Hardy, J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolar, M.; Hey, J.; Power, A.; Abushakra, S. Neurotoxic Soluble Amyloid Oligomers Drive Alzheimer’s Pathogenesis and Represent a Clinically Validated Target for Slowing Disease Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabal, A.; Alonso-Cortina, V.; Gonzalez-Vazquez, L.O.; Naves, F.J.; Del Valle, M.E.; Vega, J.A. β-Amyloid precursor protein (βAPP) in human gut with special reference to the enteric nervous system. Brain Res. Bull. 1995, 38, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guénette, S.; Strecker, P.; Kins, S. APP Protein Family Signaling at the Synapse: Insights from Intracellular APP-Binding Proteins. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannuzzi, C.; Irace, G.; Sirangelo, I. Differential effects of glycation on protein aggregation and amyloid formation. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2014, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenetz, F.; Tomita, T.; Hsieh, H.; Seabrook, G.; Borchelt, D.; Iwatsubo, T.; Sisodia, S.; Malinow, R. APP Processing and Synaptic Function. Neuron 2003, 37, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, J.P.; Walsh, D.M.; Hofmeister, J.J.; Shankar, G.M.; Kuskowski, M.A.; Selkoe, D.J.; Ashe, K.H. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-β protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, D.M.; Klyubin, I.; Fadeeva, J.V.; Cullen, W.K.; Anwyl, R.; Wolfe, M.S.; Rowan, M.J.; Selkoe, D.J. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid b protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature 2002, 416, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.; Boehm, J.; Sato, C.; Iwatsubo, T.; Tomita, T.; Sisodia, S.; Malinow, R. AMPA-R Removal Underlies Aβ-induced Synaptic Depression and Dendritic Spine Loss. Neuron 2006, 52, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, G.M.; Li, S.; Mehta, T.H.; Garcia-Munoz, A.; Shepardson, N.E.; Smith, I.; Brett, F.M.; Farrell, M.A.; Rowan, M.J.; Lemere, C.A.; et al. Amyloid-β protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmalm, G.; Hong, W.; Wang, Z.; Liu, W.; O’Malley, T.T.; Sun, X.; Frosch, M.P.; Selkoe, D.J.; Portelius, E.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. Identification of neurotoxic cross-linked amyloid-β dimers in the Alzheimer’s brain. Brain 2019, 142, 1441–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Selkoe, D.J. A mechanistic hypothesis for the impairment of synaptic plasticity by soluble Aβ oligomers from Alzheimer’s brain. J. Neurochem. 2020, 154, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, J.; Selkoe, D.J. The Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Progress and Problems on the Road to Therapeutics. Science 2002, 297, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villeneuve, S.; Jagust, W.J. Imaging vascular disease and amyloid in the aging brain: Implications for treatment. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 2, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagno, G.; Ferro, F.; Fluca, A.L.; Janjusevic, M.; Rossi, M.; Sinagra, G.; Beltrami, A.P.; Moretti, R.; Aleksova, A. From brain to heart: Possible role of amyloid-β in ischemic heart disease and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Int. J. Molec. Sci. 2020, 21, 9655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turgut, G.Ç.; Pepe, N.A.; Ekiz, Y.C.; Şenol, H.; Şen, A. Therapeutic Potential of Nitrogen-Substituted Oleanolic Acid Derivatives in Neuroinflammatory and Cytokine Pathways: Insights From Cell-Based and Computational Models. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202500269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.O.; Ban, J.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Jeong, H.Y.; Lee, I.S.; Song, K.S.; Bae, K.; Seong, Y.H. Aralia cordata Protects Against Amyloid β Protein (25–35)–Induced Neurotoxicity in Cultured Neurons and Has Antidementia Activities in Mice. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 111, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, K.; Koike, S.; Ogasawara, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Koyama, K.; Kinoshita, K. Inhibition of amyloid β aggregation and protective effect on SH-SY5Y cells by triterpenoid saponins from the cactus Polaskia chichipe. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 3377–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, C.F.; Yang, Z.L. Triterpene saponins from the roots of Dipsacus asper and their protective effects against the Aβ25–35 induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cells. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, K.; Shimoyama, T.; Kawazu, R.; Sasaki, H.; Koyama, K.; Takahashi, K.; Kinoshita, K. Amyloid β aggregation inhibitory activity of triterpene saponins from the cactus Stenocereus pruinosus. J. Nat. Med. 2021, 75, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.d.A.; Ko, H.J.; Lee, H.; Aminul Haque, M.; Park, I.S.; Lee, D.S.; Woo, E. Oleanane triterpenoids from Akebiae Caulis exhibit inhibitory effects on Aβ42 induced fibrillogenesis. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2017, 40, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivatsa, V.S.; Parameswari, R.P.; Roy, A. Evaluation of the Antioxidant and Anti-Alzheimer’s Activity of Oleanolic Acid: An In-vitro Study. J. Clin. Diagnost. Res. 2025, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kanegan, M.J.; Dunn, D.E.; Kaltenbach, L.S.; Shah, B.; He, D.N.; McCoy, D.D.; Yang, P.; Peng, J.; Shen, L.; Du, L.; et al. Dual activities of the anti-cancer drug candidate PBI-05204 provide neuroprotection in brain slice models for neurodegenerative diseases and stroke. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumont, M.; Wille, E.; Calingasan, N.Y.; Tampellini, D.; Williams, C.; Gouras, G.K.; Liby, K.; Sporn, M.; Nathan, C.; Beal, M.F.; et al. Triterpenoid CDDO-methylamide improves memory and decreases amyloid plaques in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2009, 109, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chishti, M.A.; Yang, D.S.; Janus, C.; Phinney, A.L.; Horne, P.; Pearson, J.; Strome, R.; Zuker, N.; Loukides, J.; French, J.; et al. Early-onset Amyloid Deposition and Cognitive Deficits in Transgenic Mice Expressing a Double Mutant Form of Amyloid Precursor Protein 695. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 21562–21570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.A.; McCoy, M.K.; Sporn, M.B.; Tansey, M.G. The synthetic triterpenoid CDDO-methyl ester modulates microglial activities, inhibits TNF production, and provides dopaminergic neuroprotection. J. Neuroinflamm. 2008, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Sun, W.; Zhang, L.; Guo, W.; Xu, J.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y. Oleanolic Acid Ameliorates Aβ25-35 Injection-induced Memory Deficit in Alzheimer’s Disease Model Rats by Maintaining Synaptic Plasticity. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2018, 17, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitta, A.; Fukuta, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Nabeshima, T. Continuous Infusion of BETA-Amyloid Protein into the Rat Cerebral Ventricle Induces Learning Impairment and Neuronal and Morphological Degeneration. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1997, 73, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, E.R.; Lasky, D.J.; Rippentrop, O.J.; Clark, J.P.; Wright, S.; Jones, M.V.; Anderson, R.M. Reversal of neuronal tau pathology via adiponectin receptor activation. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, K.; Liu, F.; Gong, C.X.; Grundke-Iqbal, I. Tau in Alzheimer Disease and Related Tauopathies. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2010, 7, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, M.S.; Tewari, D.; Sharma, G.; Kabir, M.T.; Barreto, G.E.; Bin-Jumah, M.N.; Perveen, A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Ashraf, G.M. Molecular Mechanisms of ER Stress and UPR in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 2902–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busche, M.A.; Hyman, B.T. Synergy between amyloid-β and tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 1183–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Song, Z.; Tapayan, A.S.; Singh, K.; Wang, K.W.; Chien Hagar, H.T.; Zhang, J.; Kim, H.; Thepsuwan, P.; Kuo, M.; et al. Effects of Heparan Sulfate Trisaccharide Containing Oleanolic Acid in Attenuating Hyperphosphorylated Tau-Induced Cell Dysfunction Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 3356–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandar, C.C.; Sen, D.; Maity, A. Anti-inflammatory Potential of GSK-3 Inhibitors. Curr. Drug Targets 2021, 22, 1464–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Sze, S.C.W.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, P.; Wang, Y.; Deng, Q.; Yung, K.K.; Zhang, S. 20(S)-protopanaxadiol and oleanolic acid ameliorate cognitive deficits in APP/PS1 transgenic mice by enhancing hippocampal neurogenesis. J. Ginseng Res. 2021, 45, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarbox, H.E.; Branch, A.; Fried, S.D. Proteins with cognition-associated structural changes in a rat model of aging exhibit reduced refolding capacity. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadt3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Mesulam, M.M.; Cuello, A.C.; Farlow, M.R.; Giacobini, E.; Grossberg, G.T.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Vergallo, A.; Cavedo, E.; Snyder, P.J.; et al. The cholinergic system in the pathophysiology and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2018, 141, 1917–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciotto, M.R.; Higley, M.J.; Mineur, Y.S. Acetylcholine as a Neuromodulator: Cholinergic Signaling Shapes Nervous System Function and Behavior. Neuron 2012, 76, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahnestock, M.; Shekari, A. ProNGF and Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haam, J.; Yakel, J.L. Cholinergic modulation of the hippocampal region and memory function. J. Neurochem. 2017, 142, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, C.; Bordoni, B. Physiology, Acetylcholine; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam, M.M.; Guillozet, A.; Shaw, P.; Levey, A.; Duysen, E.G.; Lockridge, O. Acetylcholinesterase knockouts establish central cholinergic pathways and can use butyrylcholinesterase to hydrolyze acetylcholine. Neuroscience 2002, 110, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, P.B. Hepatotoxic Effects of Tacrine Administration in Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1994, 271, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Bloemer, J. Side effects of drugs used in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. In Side Effects of Drugs Annual; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.A.; Dar, T.A.; Dar, P.A.; Ganie, S.A.; Kamal, M.A. A Current Perspective on the Inhibition of Cholinesterase by Natural and Synthetic Inhibitors. Curr. Drug Metab. 2017, 18, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhadra, S.; Dalai, M.K.; Chanda, J.; Mukherjee, P.K. Evaluation of Bioactive Compounds as Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors from Medicinal Plants. In Evidence-Based Validation of Herbal Medicine; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 273–306. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, A.; Çağlar, P.; Dirmenci, T.; Gören, N.; Topçu, G. A Novel Isopimarane Diterpenoid with Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activity from Nepeta sorgerae, an Endemic Species to the Nemrut Mountain. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2012, 7, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X. Elsholtzia rugulosa: Phytochemical Profile and Antioxidant, Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease, Antidiabetic, Antibacterial, Cytotoxic and Hepatoprotective Activities. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2022, 77, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaei-Kahnamoei, M.; Saeedi, M.; Rastegari, A.; Shams Ardekani, M.R.; Akbarzadeh, T.; Khanavi, M. Phytochemical Analysis and Evaluation of Biological Activity of Lawsonia inermis Seeds Related to Alzheimer’s Disease. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 5965061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Muhammad, S.; Shah, M.R.; Khan, A.; Rashid, U.; Farooq, U.; Ullah, F.; Sadiq, A.; Ayaz, M.; Ali, M.; et al. Neurologically Potent Molecules from Crataegus oxyacantha; Isolation, Anticholinesterase Inhibition, and Molecular Docking. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, S.; Mirgos, M.; Morlock, G.E. Effect-directed analysis of fresh and dried elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) via hyphenated planar chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1426, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, J.; Bretón, J.L.; de la Fuente, G.; González, A.G. Terpenoids of the micromerias.-I. Two new triterpenic acids isolatedfrom micromeria benthami webb et berth. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967, 8, 4649–4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. An updated review on the parasitic herb of Cuscuta reflexa Roxb. J. Chin. Integr. Med. 2012, 10, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çulhaoğlu, B.; Yapar, G.; Dirmenci, T.; Topçu, G. Bioactive constituents of Salvia chrysophylla Stapf. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, S.; Singh, P.P.; Bora, P.S.; Sharma, U. Chemometric guided isolation of new triterpenoid saponins as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from seeds of Achyranthes bidentata Blume. Fitoterapia 2024, 175, 105925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loesche, A.; Köwitsch, A.; Lucas, S.D.; Al-Halabi, Z.; Sippl, W.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Csuk, R. Ursolic and oleanolic acid derivatives with cholinesterase inhibiting potential. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 85, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwajgier, D.; Baranowska-Wójcik, E. Terpenes and Phenylpropanoids as Acetyl- and Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors: A Comparative Study. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2019, 16, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, G.; Huerta-Reyes, M.; González-Cortazar, M.; Zamilpa, A.; Jiménez-Ferrer, E.; Silva-García, R.; Román-Ramos, R.; Aguilar-Rojas, A. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-acetylcholinesterase activities of Bouvardia ternifolia: Potential implications in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2015, 38, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thandivel, S.; Rajan, P.; Gunasekar, T.; Arjunan, A.; Khute, S.; Kareti, S.R.; Paranthaman, S. In silico molecular docking and dynamic simulation of anti-cholinesterase compounds from the extract of Catunaregam spinosa for possible treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępnik, K.; Kukula-Koch, W.; Plazinski, W.; Rybicka, M.; Gawel, K. Neuroprotective Properties of Oleanolic Acid—Computational-Driven Molecular Research Combined with In Vitro and In Vivo Experiments. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, N.; Friedrich, S.; Temml, V.; Schuster, D.; Siewert, B.; Csuk, R. N-methylated diazabicyclo [3.2.2]nonane substituted triterpenoic acids are excellent, hyperbolic and selective inhibitors for butyrylcholinesterase. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 227, 113947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, A.V.; Poptsov, A.I.; Heise, N.V.; Csuk, R.; Kazakova, O.B. Diethoxyphosphoryloxy-oleanolic acid is a nanomolar-inhibitor of butyrylcholinesterase. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2024, 103, e14506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loesche, A.; Kahnt, M.; Serbian, I.; Brandt, W.; Csuk, R. Triterpene-Based Carboxamides Act as Good Inhibitors of Butyrylcholinesterase. Molecules 2019, 24, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenol, H.; Çelik Turgut, G.; Şen, A.; Sağlamtaş, R.; Tuncay, S.; Gülçin, İ.; Gülaçtı, T. Synthesis of nitrogen-containing oleanolic acid derivatives as carbonic anhydrase and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Med. Chem. Res. 2023, 32, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, A.V.; Zueva, I.V.; Petrov, K.A. Synthesis and Cholinesterase Inhibitory Potency of 2,3-Indolo-oleanolic Acid and Some Related Derivatives. Molbank 2023, 2023, M1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, B.; Koch, L.; Hoenke, S.; Deigner, H.P.; Csuk, R. The presence of a cationic center is not alone decisive for the cytotoxicity of triterpene carboxylic acid amides. Steroids 2020, 163, 108713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenke, S.; Christoph, M.A.; Friedrich, S.; Heise, N.; Brandes, B.; Deigner, H.P.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Csuk, R. The Presence of a Cyclohexyldiamine Moiety Confers Cytotoxicity to Pentacyclic Triterpenoids. Molecules 2021, 26, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, S.J.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, H.E.; Park, S.J.; Gwon, Y.; Kim, H.; Zhang, J.; Shin, C.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Ryu, J.H. Oleanolic acid ameliorates cognitive dysfunction caused by cholinergic blockade via TrkB-dependent BDNF signaling. Neuropharmacology 2017, 113, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toide, K. Effects of scopolamine on extracellular acetylcholine and choline levels and on spontaneous motor activity in freely moving rats measured by brain dialysis. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1989, 33, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, G.; Comprido, D.; Duarte, C.B. BDNF-induced local protein synthesis and synaptic plasticity. Neuropharmacology 2014, 76, 639–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revest, J.M.; Le Roux, A.; Roullot-Lacarrière, V.; Kaouane, N.; Vallée, M.; Kasanetz, F.; Rougé-Pont, F.; Tronche, F.; Desmedt, A.; Piazza, P.V. BDNF-TrkB signaling through Erk1/2MAPK phosphorylation mediates the enhancement of fear memory induced by glucocorticoids. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Le, X.T.; Van Nguyen, T.; Phung, H.N.; Pham, H.T.N.; Nguyen, K.M.; Matsumoto, K. Ursolic acid and its isomer oleanolic acid are responsible for the anti-dementia effects of Ocimum sanctum in olfactory bulbectomized mice. J. Nat. Med. 2022, 76, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.B.; Tirupattur, S.P.; Vishwakarma, N.; Katwa, L.C. Essential Pieces of the Puzzle: The Roles of VEGF and Dopamine in Aging. Cells 2025, 14, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inada, C.; Niu, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Le, X.T.; Fujiwara, H. Possible involvement of VEGF signaling system in rescuing effect of endogenous acetylcholine on NMDA-induced long-lasting hippocampal cell damage in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. Neurochem. Int. 2014, 75, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Ohtake, H.; Oka, J.I.; Fujiwara, H. Endogenous acetylcholine regulates neuronal and astrocytic vascular endothelial growth factor expression levels via different acetylcholine receptor mechanisms. Neurochem. Int. 2018, 118, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.H.; Wu, Y.C.; Liu, I.M.; Cheng, J.T. Release of acetylcholine to raise insulin secretion in Wistar rats by oleanolic acid, one of the active principles contained in Cornus officinalis. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 404, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneka, M.T.; van der Flier, W.M.; Jessen, F.; Hoozemanns, J.; Thal, D.R.; Boche, D.; Brosseron, F.; Teunissen, C.; Zetterberg, H.; Jacobs, A.H.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2025, 25, 321–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solito, E.; Sastre, M. Microglia function in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2012, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, A.; Tremblay, M.Ã.; Wake, H. Never-resting microglia: Physiological roles in the healthy brain and pathological implications. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2014, 8, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; Khoury, J.E.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swardfager, W.; Lanctt, K.; Rothenburg, L.; Wong, A.; Cappell, J.; Herrmann, N. A meta-analysis of cytokines in Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 68, 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fruhwürth, S.; Zetterberg, H.; Paludan, S.R. Microglia and amyloid plaque formation in Alzheimer’s disease—Evidence, possible mechanisms, and future challenges. J. Neuroimmunol. 2024, 390, 578342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisht, K.; Sharma, K.P.; Lecours, C.; Gabriela Sánchez, M.; El Hajj, H.; Milior, G.; Olmos-Alonso, A.; Gómez-Nicola, D.; Luheshi, G.; Vallières, L.; et al. Dark microglia: A new phenotype predominantly associated with pathological states. Glia 2016, 64, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, V.H.; Holmes, C. Microglial priming in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 10, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Rodriguez, R. Oleanolic Acid and Related Triterpenoids from Olives on Vascular Function: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Perspectives. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015, 22, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, N.; Wang, Y.; Honda, T.; Gribble, G.W.; Dmitrovsky, E.; Hickey, W.F.; Maue, R.A.; Place, A.E.; Porter, D.M.; Spinella, M.J.; et al. A novel synthetic oleanane triterpenoid, 2-cyano-3,12-dioxoolean-1,9-dien-28-oic acid, with potent differentiating, antiproliferative, and anti-inflammatory activity. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 336–341. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, R.; Hernández, M.; Córdova, C.; Nieto, M. Natural triterpenes modulate immune-inflammatory markers of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: Therapeutic implications for multiple sclerosis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 166, 1708–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, J.M.; Garcia-Rodriguez, S.; Espinosa, J.M.; Millan-Linares, M.C.; Rada, M.; Perona, J.S. Oleanolic acid exerts a neuroprotective effect against microglial cell activation by modulating cytokine release and antioxidant defense systems. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, G.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z. Oleanolic acid administration alleviates neuropathic pain after a peripheral nerve injury by regulating microglia polarization-mediated neuroinflammation. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 12920–12928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xia, R.; Jia, J.; Wang, L.; Li, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Oleanolic acid protects against cognitive decline and neuroinflammation-mediated neurotoxicity by blocking secretory phospholipase A2 IIA-activated calcium signals. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 99, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano-Jiménez, E.; Jiménez-Ferrer Carrillo, I.; Pedraza-Escalona, M.; Ramírez-Serrano, C.E.; Álvarez-Arellano, L.; Cortés-Mendoza, J.; Herrera-Ruiz, M.; Jiménez-Ferrer, E.; Zamilpa, A.; Tortoriello, J.; et al. Malva parviflora extract ameliorates the deleterious effects of a high fat diet on the cognitive deficit in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease by restoring microglial function via a PPAR-γ-dependent mechanism. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingale, T.D.; Gupta, G.L. Oleanolic acid-based therapeutics ameliorate rotenone-induced motor and depressive behaviors in parkinsonian male mice via controlling neuroinflammation and activating Nrf2-BDNF-dopaminergic signaling pathways. Toxicol. Mech Methods 2024, 34, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.H.; Park, K.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Kang, W.C.; Jeon, M.; Min, J.W.; Lee, W.H.; Jung, S.Y.; Ryu, J.H. Effects of oleanolic acid and ursolic acid on depression-like behaviors induced by maternal separation in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 956, 175954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Lee, S.; Lim, H.; Lee, J.; Park, J.Y.; Kwon, H.J.; Lee, I.; Ryu, Y.; Kim, J.; Shin, T.; et al. Oleanolic Acid Acetate Alleviates Symptoms of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis in Mice by Regulating Toll-Like Receptor 2 Signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 556391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, T.K.; Belkadi, A.; Kesavapany, S.; Zaremba, A.; Loh, S.L.; Bai, L.; Cohen, M.L.; Meyer, C.; Liby, K.T.; Miller, R.H.; et al. Triterpenoid modulation of IL-17 and Nrf-2 expression ameliorates neuroinflammation and promotes remyelination in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Sci. Rep. 2011, 1, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, Y.; Wang, X.; Yan, F.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, S.; Song, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X. Quinoa Saponin Ameliorates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Behavioral Disorders in Mice by Inhibiting Neuroinflammation, Modulating Gut Microbiota, and Counterbalancing Intestinal Inflammation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 4700–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.E.; Park, H.; Lee, J.E.; Kang, T.C. CDDO-Me Inhibits Microglial Activation and Monocyte Infiltration by Abrogating NFκB- and p38 MAPK-Mediated Signaling Pathways Following Status Epilepticus. Cells 2020, 9, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neymotin, A.; Calingasan, N.Y.; Wille, E.; Naseri, N.; Petri, S.; Damiano, M.; Liby, K.T.; Risingsong, R.; Sporn, M.; Beal, M.F.; et al. Neuroprotective effect of Nrf2/ARE activators, CDDO ethylamide and CDDO trifluoroethylamide, in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.K.; Perry, R.H.; Blessed, G.; Tomlinson, B.E. Changes in brain cholinesterases in senile dementia of Alzheimer type. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1978, 4, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.N.; Schmitt, F.A.; Scheff, S.W.; Ding, Q.; Chen, Q.; Butterfield, D.A.; Markesbery, W.R. Evidence of increased oxidative damage in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 2005, 64, 1152–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manczak, M.; Anekonda, T.S.; Henson, E.; Park, B.S.; Quinn, J.; Reddy, P.H. Mitochondria are a direct site of Aβ accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease neurons: Implications for free radical generation and oxidative damage in disease progression. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 1437–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramov, A.Y.; Potapova, E.V.; Dremin, V.V.; Dunaev, A.V. Interaction of Oxidative Stress and Misfolded Proteins in the Mechanism of Neurodegeneration. Life 2020, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praticò, D.; Uryu, K.; Leight, S.; Trojanoswki, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.Y. Increased Lipid Peroxidation Precedes Amyloid Plaque Formation in an Animal Model of Alzheimer Amyloidosis. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 4183–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camandola, S.; Mattson, M.P. Brain metabolism in health, aging, and neurodegeneration. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 1474–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Guo, J.; Ye, X.Y.; Xie, Y.; Xie, T. Oxidative stress: The core pathogenesis and mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 77, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, P.; Cunha, R.A.; Oliveira, C. Neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010, 16, 2766–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, F.R.; Gantner, B.N.; Sakiyama, M.J.; Kayzuka, C.; Shukla, S.; Lacchini, R.; Cunniff, B.; Bonini, M.G. ROS production by mitochondria: Function or dysfunction? Oncogene 2024, 43, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swerdlow, R.H. Mitochondria and Mitochondrial Cascades in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 62, 1403–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, B.A.I.; Chinnery, P.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction in aging: Much progress but many unresolved questions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 2015, 1847, 1347–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sut, S.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Flores, G.A.; Cusumano, G.; Koyuncu, İ.; Yuksekdag, O.; Emiliani, C.; Venanzoni, R.; Angelini, P.; Selvi, S.; et al. Hypericum empetrifolium and H. lydium as Health Promoting Nutraceuticals: Assessing Their Role Combining In Vitro In Silico and Chemical Approaches. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, J.M.; Guinda, A.; MacÍas, L.; Santos-Lozano, J.M.; Lapetra, J.; Rada, M. Free radical scavenging and a-glucosidase inhibition, two potential mechanisms involved in the anti-diabetic activity of oleanolic acid. Grasas Aceites 2016, 67, e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ye, X.; Liu, R.; Chen, H.L.; Bai, H.; Liang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Hai, C. Antioxidant activities of oleanolic acid in vitro: Possible role of Nrf2 and MAP kinases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010, 184, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; He, J.; Zhang, H.; Yao, L.; Li, H. Oleanolic acid alleviates oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease by regulating stanniocalcin-1 and uncoupling protein-2 signalling. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2020, 47, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, L.; Schwartz, M.L.; Horvath, T.L. Mitochondria controlled by UCP2 determine hypoxia-induced synaptic remodeling in the cortex and hippocampus. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 90, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.H.; Liu, Y.; Hu, H.T.; Ren, H.M.; Chen, X.L.; Xu, J.H. The effects of the total saponin of Dipsacus asperoides on the damage of cultured neurons induced by beta-amyloid protein 25-35. Anat. Sci Int. 2002, 77, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Désiré, G.N.S.; Simplice, F.H.; Guillaume, C.W.; Kamal, F.Z.; Parfait, B.; Hermann, T.D.S.; Hervé, N.A.H.; Eglantine, K.W.; Linda, D.K.J.; Roland, R.N.; et al. Cashew (Anacardium occidentale) Extract: Possible Effects on Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal (HPA) Axis in Modulating Chronic Stress. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Msibi, Z.N.P.; Mabandla, M.V. Oleanolic Acid Mitigates 6-Hydroxydopamine Neurotoxicity by Attenuating Intracellular ROS in PC12 Cells and Striatal Microglial Activation in Rat Brains. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bojuan, L.; Youdong, Z.; Lei, W.; Lixin, X.; Jinyang, M. Oleanolic Acid Alleviates Neuronal Ferroptosis in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage by Inhibiting KEAP1-Nrf2 and NF-κB Pathways. Drug Dev Res. 2025, 86, e70105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.; Yoon, H.E.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, S.J.; Koh, E.S.; Hong, Y.A.; Park, C.W.; Chang, Y.S.; Shin, S.J. Oleanolic acid attenuates renal fibrosis in mice with unilateral ureteral obstruction via facilitating nuclear translocation of Nrf2. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uruno, A.; Kadoguchi-Igarashi, S.; Saito, R.; Koiso, S.; Saigusa, D.; Chu, C.T.; Suzuki, T.; Saito, T.; Saido, T.C.; Cuadrado, A.; et al. The NRF2 inducer CDDO-2P-Im provokes a reduction in amyloid β levels in Alzheimer’s disease model mice. J. Biochem. 2024, 176, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osama, A.; Zhang, J.; Yao, J.; Yao, X.; Fang, J. Nrf2: A dark horse in Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 64, 101206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, H.; Mathew, R.O.; Cui, T. The Dark Side of Nrf2 in the Heart. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftekharzadeh, B.; Maghsoudi, N.; Khodagholi, F. Stabilization of transcription factor Nrf2 by tBHQ prevents oxidative stress-induced amyloid β formation in NT2N neurons. Biochimie 2010, 92, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, M.S. Perturbed glycogen metabolism is an Alzheimer’s disease therapeutic target. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, e071567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, F.G.; Gonçalves, R.A.; Ferreira, S.T. Impaired insulin signalling and allostatic load in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 23, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F. Lipid metabolism and Alzheimer’s disease: Clinical evidence, mechanistic link and therapeutic promise. FEBS J. 2023, 290, 1420–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Chu, C.; Qin, Q.; Shen, H.; Wen, L.; Tang, Y.; Qu, M. Lipid metabolism and oxidative stress in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Brain Pathol. 2024, 34, e13202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squier, T.C. Oxidative stress and protein aggregation during biological aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2001, 36, 1539–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Johansen, V.B.I.; Legido-Quigley, C. Bridging brain insulin resistance to Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2024, 49, 939–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabi, F.; Moassesfar, M.; Nakhaie, T.; Bagherian, M.; Hosseinpour, N.; Hashemi, M. A systematic review on type 3 diabetes: Bridging the gap between metabolic dysfunction and Alzheimer’s disease. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, J.; Wandosell, F.; Hernández, F. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis and glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitors. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2010, 10, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothandan, D.; Singh, D.S.; Yerrakula, G.; Backkiyashree, D.; Pratibha, N.; Sophia, V.S.; Ramya, A.; Ramya, S.; Keshavini, S.; Jagadheeshwari, M. Advanced Glycation End Products-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease and Its Novel Therapeutic Approaches: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e61373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Folstein, M. Insulin, insulin-degrading enzyme and amyloid-β peptide in Alzheimer’s disease: Review and hypothesis. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Li, C. Linking type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6557–6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy revisited: A conversation with Christian de Duve. Autophagy 2008, 4, 740–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; De Felice, F.G.; Fernandez, S.; Chen, H.; Lambert, M.P.; Quon, M.J.; Krafft, G.A.; Klein, W.L. Amyloid beta oligomers induce impairment of neuronal insulin receptors. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.J.; Park, S.S.; Mok, J.O.; Lee, T.K.; Park, C.S.; Park, S.A. Increased expression of three-repeat isoforms of tau contributes to tau pathology in a rat model of chronic type 2 diabetes. Exp. Neurol. 2011, 228, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, J.M.; Guinda, A.; Delgado, T.; Rada, M.; Cayuela, J.A. Biochemical basis of the antidiabetic activity of oleanolic acid and related pentacyclic triterpenes. Diabetes 2013, 62, 1791–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwakalukwa, R.; Amen, Y.; Nagata, M.; Shimizu, K. Postprandial Hyperglycemia Lowering Effect of the Isolated Compounds from Olive Mill Wastes—An Inhibitory Activity and Kinetics Studies on α-Glucosidase and α-Amylase Enzymes. ACS Omega 2018, 5, 20070–20079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; He, H.; Ma, H.; Tu, B.; Li, J.; Guo, S.; Chen, S.; Cao, N.; Zheng, W.; Tang, X.; et al. Oleanolic acid indole derivatives as novel α-glucosidase inhibitors: Synthesis, biological evaluation, and mechanistic analysis. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 107, 104580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Ma, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, L.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, C.; Lin, L.; Sun, H.; et al. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Substituted Pyrazole-Fused Oleanolic Acid Derivatives as Novel Selective α-Glucosidase Inhibitors. Chem. Biodivers. 2023, 20, e202201178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Mehan, S.; Khan, Z.; Das Gupta, G.; Narula, A.S. Therapeutic potential of oleanolic acid in modulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR/STAT-3/GSK-3β signaling pathways and neuroprotection against methylmercury-induced neurodegeneration. Neurochem. Int. 2024, 180, 105876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, C.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Tan, L. Association between Alzheimer’s disease and metabolic syndrome: Unveiling the role of dyslipidemia mechanisms. Brain Netw. Disord. 2025, 1, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Qin, C. Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis: Standing at the crossroad of lipid metabolism and immune response. Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, M.A.; Laurent, B.; Plourde, M.; Wood, L. APOE and Alzheimer ’ s Disease: From Lipid Transport to Physiopathology and Therapeutics. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 630502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genin, E.; Hannequin, D.; Wallon, D.; Sleegers, K.; Hiltunen, M.; Combarros, O.; Bullido, M.J.; Engelborghs, S.; Deyn, P.; Berr, C.; et al. APOE and Alzheimer disease: A major gene with semi-dominant inheritance. Mol. Psychiatry 2011, 16, 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Liang, Z.; Huang, Y. APOE4 homozygosity is a new genetic form of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1241–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raulin, A.C.; Doss, S.V.; Trottier, Z.A.; Ikezu, T.C.; Bu, G.; Liu, C.C. ApoE in Alzheimer’s disease: Pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies. Mol. Neurodegener. 2022, 17, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Navia-Pelaez, J.M.; Choi SHo Miller, Y.I. Macrophage inflammarafts in atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2023, 34, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaji, S.; Berghoff, S.A.; Spieth, L.; Schlaphoff, L.; Sasmita, A.O.; Vitale, S.; Büschgens, L.; Kedia, S.; Zirngibl, M.; Nazarenko, T.; et al. Apolipoprotein E aggregation in microglia initiates Alzheimer’s disease pathology by seeding β-amyloidosis. Immunity 2024, 57, 2651–2668.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, S.; Jian, L.; Johnsen, R.; Chew, S.; Mamo, J.C.L. β-Amyloid or its precursor protein is found in epithelial cells of the small intestine and is stimulated by high-fat feeding. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2007, 18, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takechi, R.; Galloway, S.; Pallebage-Gamarallage, M.; Wellington, C.; Johnsen, R.; Mamo, J.C. Three-dimensional colocalization analysis of plasma-derived apolipoprotein B with amyloid plaques in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 131, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.P.; Pal, S.; Gennat, H.C.; Vine, D.F.; Mamo, J.C.L. The incorporation and metabolism of amyloid-β into chylomicron-like lipid emulsions. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2003, 5, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamo, J.C.L.; Jian, L.; James, A.P.; Flicker, L.; Esselmann, H.; Wiltfang, J. Plasma lipoprotein β-amyloid in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment. Ann. Clin. Biochem. Int. J. Lab. Med. 2008, 45, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, X.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liang, X.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. Gut-derived β-amyloid: Likely a centerpiece of the gut–brain axis contributing to Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2167172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudinova, N.V.; Berezov, T.T.; Koudinov, A.R. Multiple inhibitory effects of Alzheimer’s peptide Abeta1-40 on lipid biosynthesis in cultured human HepG2 cells. FEBS Lett. 1996, 395, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.L.; Aung, H.H.; Wilson, D.W.; Anderson, S.E.; Rutledge, J.C.; Rutkowsky, J.M. Triglyceride-Rich lipoprotein lipolysis products increase Blood-Brain barrier transfer coefficient and induce astrocyte lipid droplets and cell stress. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2017, 312, C500–C516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.F.; Anderson, S.; Mayo, P.; Aung, H.H.; Walton, J.H.; Rutledge, J.C. Characterizing blood–brain barrier perturbations after exposure to human triglyceride-rich lipoprotein lipolysis products using MRI in a rat model. Magn. Reson. Med. 2016, 76, 1246–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, G.L.; Kaye, J.A.; Moore, M.; Waichunas, D.; Carlson, N.E.; Quinn, J.F. Blood-brain barrier impairment in Alzheimer disease: Stability and functional significance. Neurology 2007, 68, 1809–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toscano, R.; Millan-Linares, M.C.; Lemus-Conejo, A.; Claro, C.; Sanchez-Margalet, V.; Montserrat-de la Paz, S. Postprandial triglyceride-rich lipoproteins promote M1/M2 microglia polarization in a fatty-acid-dependent manner. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 75, 108248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, J.M.; Castellano, J.M.; Garcia-Rodriguez, S.; Quintero-Flórez, A.; Carrasquilla, N.; Perona, J.S. Lipophilic Bioactive Compounds Transported in Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins Modulate Microglial Inflammatory Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Mudher, A. Alzheimer’s Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: A Critical Assessment of the Shared Pathological Traits. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trefts, E.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK: Restoring metabolic homeostasis over space and time. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 3677–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C. Unfolding the role of protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 4, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuanalo-Contreras, K.; Schulz, J.; Mukherjee, A.; Park, K.W.; Armijo, E.; Soto, C. Extensive accumulation of misfolded protein aggregates during natural aging and senescence. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 14, 1090109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niccoli, T.; Partridge, L. Ageing as a Risk Factor for Disease. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, R741–R752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoli, D.; Boulay, K.; Kazak, L.; Pollak, M.; Mallette, F.; Topisirovic, I.; Hulea, L. mTOR as a central regulator of lifespan and aging. F1000Research 2019, 8, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilman, P.; Podlutskaya, N.; Hart, M.J.; Debnath, J.; Gorostiza, O.; Bredesen, D.; Richardson, A.; Strong, R.; Galvan, V. Inhibition of mTOR by Rapamycin Abolishes Cognitive Deficits and Reduces Amyloid-β Levels in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Richardson, A.; Strong, R.; Oddo, S. Inducing Autophagy by Rapamycin Before, but Not After, the Formation of Plaques and Tangles Ameliorates Cognitive Deficits. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeffer, C.A.; Klann, E. mTOR signaling: At the crossroads of plasticity, memory and disease. Trends Neurosci. 2010, 33, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado, A.; Kügler, S.; Lastres-Becker, I. Pharmacological targeting of GSK-3 and NRF2 provides neuroprotection in a preclinical model of tauopathy. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado, A. Structural and functional characterization of Nrf2 degradation by glycogen synthase kinase 3/β-TrCP. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 88, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotolongo, K.; Ghiso, J.; Rostagno, A. Nrf2 activation through the PI3K/GSK-3 axis protects neuronal cells from Aβ-mediated oxidative and metabolic damage. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahn, G.; Park, J.S.; Yun, U.J.; Lee, Y.J.; Choi, Y.; Park, J.S.; Baek, S.H.; Choi, B.Y.; Cho, Y.S.; Kim, H.K.; et al. NRF2/ARE pathway negatively regulates BACE1 expression and ameliorates cognitive deficits in mouse Alzheimer’s models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 12516–12523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, T.P.; Johnson, D.A.; Johnson, J.A. Activation of the Nrf2-ARE pathway by siRNA knockdown of Keap1 reduces oxidative stress and provides partial protection from MPTP-mediated neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology 2012, 33, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.; Liu, H.; Ping, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhi, L.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, F.; Song, C.; Zhang, Z.; Song, J. CDDO-Im exerts antidepressant-like effects via the Nrf2/ARE pathway in a rat model of post-stroke depression. Brain Res. Bull. 2021, 173, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukundwa, A.; Mukaratirwa, S.; Masola, B. Effects of oleanolic acid on the insulin signaling pathway in skeletal muscle of streptozotocin-induced diabetic male Sprague-Dawley rats. J. Diabetes 2016, 8, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, M.; Gartlon, J.; Dawson, L.A.; Atkinson, P.J.; Pardon, M.C. A state of delirium: Deciphering the effect of inflammation on tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 94, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Yuan, D. MiR-155/GSK-3β mediates anti-inflammatory effect of Chikusetsusaponin IVa by inhibiting NF-κB signaling pathway in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cell. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Cao, Y.; Li, P.; Tang, X.; Yang, M.; Gu, S.; Xiong, K.; Li, T.; Xiao, T. Oleanolic Acid Induces Autophagy and Apoptosis via the AMPK-mTOR Signaling Pathway in Colon Cancer. J. Oncol. 2021, 2021, 8281718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Hang, T.J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wu, X.L.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Y. Determination of oleanolic acid in human plasma and study of its pharmacokinetics in Chinese healthy male volunteers by HPLC tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2006, 40, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.J.; Liu, X.; Li, P.M.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X.L. Pharmacokinetic profiles of oleanolic acid formulations in healthy Chinese male volunteers. Chin. Pharm. J. 2010, 45, 621–626. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, J.; Chang, Q.; Chan, C.K.; Meng, Z.Y.; Wang, G.N.; Sun, J.B.; Wang, Y.T.; Tong, H.H.Y.; Zheng, Y. Formulation development and bioavailability evaluation of a self-nanoemulsified drug delivery system of oleanolic acid. AAPS PharmSciTech 2009, 10, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Huang, X.; Dou, J.; Zhai, G.; Lequn, S. Self-microemulsifying drug delivery system for improved oral bioavailability of oleanolic acid: Design and evaluation. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013, 8, 2917–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, M.; Castellano, J.M.; Perona, J.S.; Guinda, Á. GC-FID determination and pharmacokinetic studies of oleanolic acid in human serum. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2015, 29, 1687–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-González, A.; Espinosa-Cabello, J.M.; Cerrillo, I.; Montero-Romero, E.; Rivas-Melo, J.J.; Romero-Báez, A.; Jiménez-Andreu, M.D.; Ruíz-Trillo, C.A.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, A.; Martínez-Ortega, A.J.; et al. Bioavailability and systemic transport of oleanolic acid in humans, formulated as a functional olive oil. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 9681–9694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Lozano, J.M.; Rada, M.; Lapetra, J.; Guinda, Á.; Jiménez-Rodríguez, M.C.; Cayuela, J.A.; Lugo, A.A.; Vilches-Arenas, A.; Gómez-Martín, A.M.; Ortega-Calvo, M.; et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes in prediabetic patients by using functional olive oil enriched in oleanolic acid: The PREDIABOLE study, a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2019, 21, 2526–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, J.M.; Quintero-Flórez, A.; Carrasquilla, N.; Montero, E.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, A.; Castellano, J.M.; Perona, J.S. Bioactive compounds in pomace olive oil modulate the inflammatory response elicited by postprandial triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in BV-2 cells. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 8987–8999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, O.J.; Pujadas, M.; Gleeson, S.B.; Mesa-García, M.D.; Pastor, A.; Kotronoulas, A.; Fitó, M.; Covas, M.I.; Fernández Navarro, J.R.; Espejo, J.A.; et al. Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometric determination of triterpenes in human fluids: Evaluation of markers of dietary intake of olive oil and metabolic disposition of oleanolic acid and maslinic acid in humans. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2017, 990, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Main Findings | Experimental Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| OA and nitrogen-substituted derivatives | Significant reduction in APP expression; inhibition of PSEN1 and PSEN2 | LPS-stimulated SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells | [23] |

| OA-rich ethanolic extract from Aralia cordata | Restored cell viability to 76.2% and 80% (at 1 and 5 μM) against Aβ(25–35) toxicity | Primary Sprague-Dawley rat brain cultures | [24] |

| OA saponins from Polaskia chichipe | Restored cell viability (76% and 74%); reduced Aβ(42) aggregation by 80% | SH-SY5Y cells and Thioflavin-T assay | [25] |

| OA saponins from Dipsacus asper | Reduced Aβ(25–35)-induced cytotoxicity by 26.7% | PC12 neuronal cells | [26] |

| Asperosaponin C from Akebia quinata | Significant reduction in Aβ(42) aggregation | Thioflavin-T (Th-T) assay | [28] |

| OA ranging from 5 μM to 320 μM | Anti-aggregation effect on Aβ(1–42); inhibition of BACE1 activity | In vitro assays (DPPH, ABTS, LPO) | [29] |

| 0.4 μg/mL Nerium oleander Fraction 4 (35% OA) | Neuroprotective effects against ischemic-like injury | Rat brain slices (Oxygen-glucose deprivation) | [30] |

| 800 mg of CDDO-MA/kg of chow | Improved spatial memory; decreased Aβ(42) concentrations; enhanced microglial phagocytic activity | Tg19959 mice (expressing human APP with KM670/671NL and V717F mutations) | [31] |

| OA (21.6 mg/kg) | Improved performance in maze and spatial tests; preserved neuronal and mitochondrial morphology; restored NMDAR2B, CaMKII, and PKC levels | Rats with intracerebroventricular (ICV) injections of Aβ | [34] |

| 10 nM CDDO (2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic acid) | Enhanced microglial phagocytic activity | TNF or LPS stimulated BV2 microglial cells | [33] |

| Compound | Main Findings | Experimental Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen-substituted OA derivatives | 90% reduction in Tau expression | SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell cultures | [23] |

| 5 μM OA-linked heparan sulfate derivative | Tau aggregation inhibition; reduced p-Tau-induced cytotoxicity; decreased ER stress and UPR activation | 0.5 μM p-Tau treated SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell cultures | [40] |

| 30 μM Nerium oleander Fraction 4 (35% OA) | Restored cell viability against Tau-induced neuronal degeneration | Biolistic transfection of Tau in neuronal models | [30] |

| Compound | Main Findings | Experimental Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| OA-rich plant extracts (Elsholtzia rugulosa, Lawsonia inermis, Crataegus oxyacantha) | Significant AChE inhibitory effects; associated with mood-stabilizing properties | In vitro Ellman’s assay, modified Ellman’s assay | [55,56,57] |

| Isolated OA from Salvia chrysophylla (25–200 μg/mL) | High AChE inhibitory activity, comparable to galantamine (positive control) | In vitro Ellman’s assay | [61] |

| OA ranging from 5 μM to 320 μM | 17.27 ± 0.05% at 20 μM, 84.82 ± 0.08% At 320 μM AChE inhibitory activity similar to donepezil | In vitro enzymatic assay | [29] |

| OA, 11-oxo-OA, methyl esters-OA | AChE inhibition, 11.62 ± 2.82, 4.22 ± 0.68, 3.46 ± 0.56 respectively. BChE inhibition inactive | In vitro Ellman’s assay | [63] |

| 3-O-acetylated-OA | High binding energy to BChE; theoretical strong ligand-protein interaction | In silico molecular docking analysis | [68] |

| OA | AChE inhibition IC50 9.22 µM | TLC-bioautography | [67] |

| OA derivatives | AChE inhibition 0.78 ± 0.09 (compound 9), BChE 38.8 ± 6.7 (compound 1) vs. donezepil 0.01 ± 0.0001, 5.26 ± 0.27 | In vitro Ellman’s assay | [72] |

| diethoxyphosphoryloxy-OA | BChE inhibitor Ki = 6.59 nM and Ki′ = 1.97 nM | In vitro Ellman’s assay | [69] |

| (3β)-Acetyloxy-OA derivatives | Potent BChE inhibition (95%), AChE marginal inhibition (25%) | In vitro Ellman’s assay | [68] |

| OA (0.625, 1.25, 2.5, or 5 mg/kg in ICR mice), OA 30 μM in primary neuron culture | Reversal of ACh deficits via TrkB receptor activation; increased BDNF expression and induction of LTP via MAPK ERK1/2 pathway | Male ICR mice scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment. Primary neuron culture from Sprague-Dawley | [75] |

| OA 24 mg/kg from Ocimum sanctum | Improved short- and long-term spatial memory | Olfactory bulbectomized (OBX) Swiss albino mice | [79] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Espinosa-Cabello, J.M.; Fernández-Aparicio, Á.; González-Jiménez, E.; Perez-Muñoz, G.; Castellano, J.M.; Perona, J.S. Oleanolic Acid and Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanistic Hypothesis of Therapeutic Potential. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010494

Espinosa-Cabello JM, Fernández-Aparicio Á, González-Jiménez E, Perez-Muñoz G, Castellano JM, Perona JS. Oleanolic Acid and Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanistic Hypothesis of Therapeutic Potential. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):494. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010494

Chicago/Turabian StyleEspinosa-Cabello, Juan M., Ángel Fernández-Aparicio, Emilio González-Jiménez, Gisela Perez-Muñoz, José María Castellano, and Javier S. Perona. 2026. "Oleanolic Acid and Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanistic Hypothesis of Therapeutic Potential" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010494

APA StyleEspinosa-Cabello, J. M., Fernández-Aparicio, Á., González-Jiménez, E., Perez-Muñoz, G., Castellano, J. M., & Perona, J. S. (2026). Oleanolic Acid and Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanistic Hypothesis of Therapeutic Potential. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010494