1. Introduction

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have attracted significant attention in recent years, not only due to their wide range of applications but also because of their malicious usage, including: smuggling, transfer of hazardous loads, unauthorized surveillance, cyberattacks, jamming, and more [

1]. Additionally, UAVs are extensively employed in military operations. It is well known that even inexpensive commercial models or amateur-built drones can cause severe damage to vehicles and infrastructure [

2]. Consequently, there has been rapid development in counter-Unmanned Aerial Systems (cUAS) [

3]. UAV prevention typically begins with the detection stage, followed by classification and neutralization through kinetic (physical) or non-kinetic (electronic) means [

4]. In some approaches, detection and classification are performed in a combined manner [

5].

Detecting the presence of UAVs can be accomplished using various types of sensors, including: visual, audio, radar, and radio frequency (RF) sensors [

6]. Most advanced cUAS utilize multi-modal analysis by fusing data from multiple sensors [

7]. However, when considering standalone solutions, RF-based systems are preferable. They are least sensitive to unfavorable environmental conditions such as poor weather or acoustic noise. The primary limitation of RF-based detection is its inability to identify fully autonomous UAVs that operate in radio silence [

8].

Numerous methods have been proposed in the literature for detecting or classifying RF transmissions. Many of these methods were developed specifically for spectrum sensing in cognitive radio applications, e.g., [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Conventional detection of RF signals can be either non-parametric or parametric. Methods in the first category are referred to as blind, as they do not require any a priori knowledge of the properties of the signals being detected. Energy detection is a typical blind method that identifies transmitter activity solely by estimating the power at the receiver’s input [

18]. However, this method requires an accurate estimation of noise variance and suffers from the so-called SNR wall problem, which can be mitigated using a constant false alarm rate algorithm [

19]. Another group of non-parametric methods is based on the eigenvalue decomposition of the covariance matrix [

20,

21]. For example, the ratio between the largest and smallest eigenvalue reflects the temporal correlation between received samples and may serve as an indicator of an ongoing transmission.

Parametric detection schemes rely on known characteristics of transmitted signals. One approach is to use a matched filter, which is equivalent to correlating the received waveform with a local reference pattern [

9]. Another method involves estimating the cyclic features of received signals and matching them to known values. Under the assumption that the target signals are cyclostationary, their carrier frequencies, symbol rates, or other periodic features can be estimated by identifying corresponding peaks in the spectral coherence function [

22,

23]. Cyclic analysis can also be performed in a blind manner, where the detection of peaks in the spectral coherence function (SCF) indicates the presence of a transmission.

Another group consists of machine learning (ML)-based methods that use algorithms such as support vector machines, random forests, k-nearest neighbors, discriminant analysis, and artificial neural networks [

8,

24]. Deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are especially valued for their ability to perform combined detection and classification of RF transmissions without requiring prior identification and extraction of specific features [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Instead, raw samples or their transforms are provided as input data [

30]. Some approaches employ computer vision techniques to recognize and classify transmissions on spectrograms [

5,

31,

32] or other transforms that provide graphical representations of the received waveforms’ features [

33].

Despite the undeniable advantages of CNNs, their use can be constrained by computational resource limitations. Processing data with large neural networks typically requires powerful processing units (CPUs and GPUs), which are unsuitable for UAV detectors deployed on portable, energy-efficient devices. Therefore, more conventional and less resource-intensive approaches may be preferable in such applications.

In this paper, a hypothesis is stated that it is possible to classify the model of a UAV based on the statistical characteristics of its transmissions. These statistics can be obtained by estimating fundamental parameters of transmitter activity, such as duration, bandwidth, and center frequency. It is assumed that the distributions of these parameters, or their derivatives, reveal features unique to each UAV model within the analyzed set. This conventional and straightforward approach offers relatively low complexity, as it relies on energy detection based on the spectrogram. Moreover, it does not require the extensive training phase typical of ML methods.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the methodology and procedures used to analyze RF transmissions to identify their unique features.

Section 3 presents the results based on a dataset containing captured waveforms from eight UAV models, followed by a discussion of these results in

Section 4. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the contributions and outcomes and suggests directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

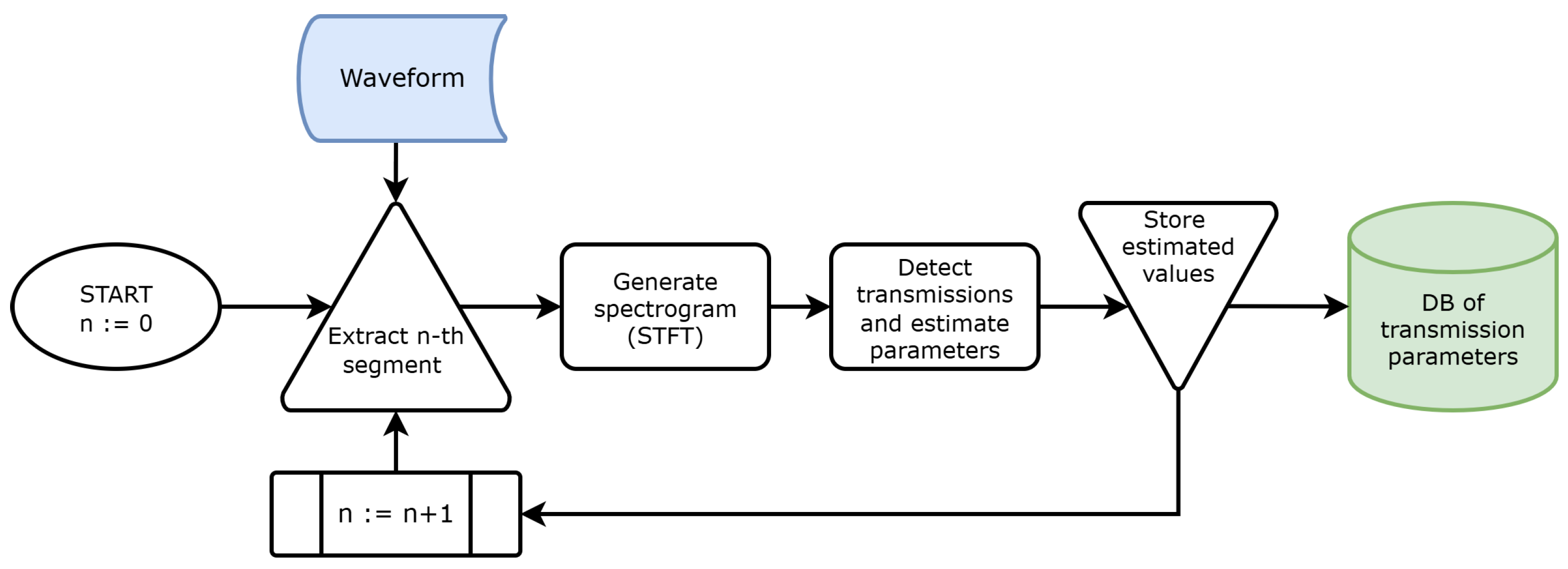

To estimate the statistical characteristics of UAV transmissions, it is necessary to capture the relevant signals using an appropriate receiver. Most UAVs operate in the ISM frequency bands of 2.45 GHz or 5.8 GHz, which span bandwidths of 100 MHz and 150 MHz, respectively. A dual-receiver software-defined radio (SDR) capable of maintaining sampling rates exceeding 100 Msps on each channel is recommended for this task. SDRs provide streams of IQ samples that represent waveforms captured at a specified center frequency. However, raw time-domain samples are unsuitable for statistical analysis because two or more transmissions may occur simultaneously within the same band, resulting in superimposed, indistinguishable waveforms. Therefore, it is necessary to transform the waveforms to obtain their time–frequency representations. The short-time Fourier transform (STFT) is used for this purpose. A spectrogram, which is the output of STFT, is calculated for each segment of the received sample stream, as shown in

Figure 1. The segment length is set to 20 ms based on preliminary observations of UAV transmission durations. It was found that transmissions rarely exceed several milliseconds, so a single segment is likely to contain an entire transmission or even multiple transmissions. Waveforms are recorded in complex short data format, meaning that both the real and imaginary components are stored as 16-bit integers. With a sampling rate of 125 MHz, each segment consists of 2.5 million samples (10 million bytes).

Spectrograms are calculated for each segment using the STFT, according to the following formula:

where

is the input waveform,

is the Hamming window function,

m denotes the number of samples by which each window is offset from the beginning of the analyzed waveform, and

is the number of samples per window. A spectrogram represents the distribution of received power on the time–frequency plane. Providing appropriate spectral resolution is necessary for accurately detecting regions corresponding to transmissions. In terms of frequency, a resolution of 100 kHz was assumed, so the number of FFT points in each STFT window is expressed as

, where

is the sampling rate in samples per second. The temporal resolution was set to 40 μs. However, to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), the spectrogram is initially calculated with 2 μs resolution, and then every 20 consecutive columns are averaged. This means that the hop size between consecutive STFT windows for the initial spectrogram calculation is set to

samples. Temporal averaging reduces the variance of the spectrogram in the time domain, which improves the accuracy of determining the time intervals during which transmission is active.

An example spectrogram of a waveform sampled at

= 125 MHz is shown in

Figure 2a. In this segment, a total of nine transmissions are present. Six wideband transmissions correspond to a video stream from the UAV to the remote controller (RC), while three short, narrowband transmissions represent control packets from the RC to the UAV. As shown, the video packets are transmitted at the same center frequency, whereas the control transmissions follow a frequency-hopping scheme. A slice of the spectrogram at the center frequency of the video channel (approximately −26 MHz) is shown in

Figure 2b. In consequence of temporal averaging, the time instants corresponding to the beginnings and endings of the six video transmissions are clearly visible.

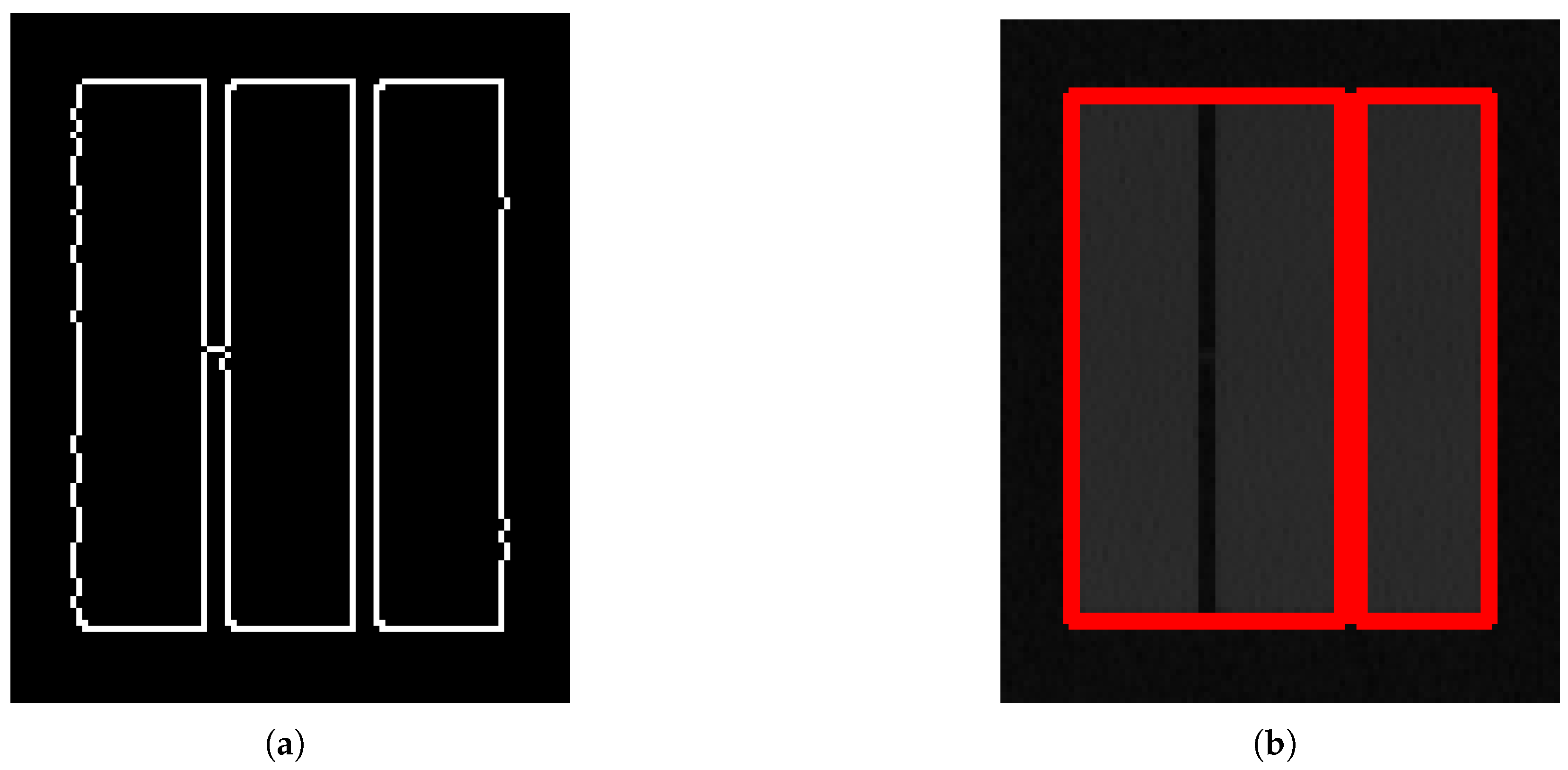

Once a spectrogram is generated, it undergoes further processing to identify regions corresponding to actual transmissions. A straightforward approach for this task would be to apply energy detection to waveforms corresponding to specific frequency bins (as shown in

Figure 2b). Energy detection involves identifying segments of the waveform where consecutive values exceed a predefined threshold. However, applying this procedure individually to all frequency bins of the spectrogram is computationally inefficient. Therefore, in this work, an alternative approach based on computer vision techniques was employed. The procedure is illustrated in

Figure 3. First, the spectrogram is normalized and converted to a grayscale image. This involves mapping the magnitude spectrogram values proportionally onto an array of bytes ranging from 0 (black, representing the lowest spectrogram value) to 255 (white, representing the highest value). Next, a two-dimensional convolution with a 5 px by 5 px Gaussian filter is applied to slightly blur the image. This blurring acts as a low-pass filter, reducing noise variance while preserving transitions related to transmitter activity. The blurred image is then processed using an edge detection function that employs the Canny algorithm. The Canny algorithm is a widely used method for detecting vertical, horizontal, and diagonal edges in images, making it suitable for this application. Since the Canny algorithm implements hysteresis thresholding, two thresholds must be specified; in this case, they were set to 10 and 20, respectively. Subsequently, contours—defined as closed shapes bounded by multiple edges—are detected throughout the image. Each contour is then enclosed within a bounding rectangle, the interior of which is assumed to represent a region with active transmission. All the aforementioned processing steps are implemented using the OpenCV library with the respective functions: GaussianBlur(), Canny(), findContours(), and boundingRect(). Example results are presented in

Figure 4.

Transmission durations and their bandwidths are estimated based on the width and height of the rectangles’ interiors, respectively. Each unit on the vertical axis corresponds to 100 kHz, while units on the horizontal axis represent a 40 μs raster. Despite applying Gaussian blurring, some residual artifacts or clutter caused by noise or interference may lead to false detections. To mitigate this, lower bounds are established for the transmission dimensions on the spectrogram. Based on observations, it is assumed that a UAV transmission lasts not less than 200 μs and has a bandwidth of at least 500 kHz. Therefore, rectangles smaller than 5 pixels in any dimension are discarded. Additionally, transmissions that are clipped—partially extending beyond the spectrogram—can result in erroneous estimates of duration or bandwidth. To exclude such partially captured transmissions, rectangles with at least one side touching the spectrogram border are also discarded.

Apart from durations and bandwidths, start times and center frequencies are estimated for each valid transmission. These estimates are stored in separate CSV files for each recording (i.e., for each specific scenario involving a given UAV).

The resulting data on fundamental parameters of UAV transmissions are analyzed to obtain statistical information useful for classifying UAV models. The first step is to identify all possible bandwidths for a given UAV. Next, transmissions are clustered based on their bandwidths, and further analysis of the distribution of transmission durations is conducted separately for each cluster. Additional statistics are also determined to enhance the classification of UAV models. The steps outlined above are explained in greater detail in the next section.

3. Results

The approach proposed in this paper is evaluated using a large dataset consisting of binary files containing streams of samples of received signals from UAVs paired with RCs. The data were collected during a measurement campaign conducted in an anechoic chamber. This campaign involved recording transmissions from eight UAV models across various scenarios, including landed, take-off, and hovering states. (For three models, measurements in the hovering state were omitted due to issues with remote control operation in the indoor environment.) For each scenario, a waveform with a total duration of 32 s was captured. The recordings were made using an NI Ettus USRP X410 SDR, simultaneously in the 2.4 GHz and 5.8 GHz bands, with a sampling rate of 125 MHz in each band.

Table 1 lists all the UAV models used in the measurements; the numbers assigned to each model are used for further reference.

The last column shows the total number of transmissions detected for each UAV. Significant differences between these values are evident, primarily because some scenarios could not be conducted with DJI Matrice models. Additionally, variations in packet transmission rates may occur due to differences in the radio interfaces used, which can vary even among drones of the same brand.

3.1. Analysis of Transmission Bandwidths

As mentioned earlier, the analysis began by estimating the distribution of observed transmission bandwidths. For each UAV, histograms were generated using all captured waveforms (i.e., without distinguishing between flight modes or frequency bands). An example of such a histogram, obtained for the DJI Mini 2, is shown in

Figure 5. Distinct peaks corresponding to the typical bandwidths for this UAV are clearly visible. The histogram bin resolution was set to 100 kHz. A bin center is considered to represent a valid transmission bandwidth if the sum of its count and the counts of ±2 neighboring bins constitute at least five percent of all observations. For the tested DJI models, five possible bandwidths were identified; their distributions are shown in

Table 2. Tested Autel drones also utilize a subset of five possible bandwidths, although most differ from those of DJI. The respective distributions are provided in

Table 3.

3.2. Analysis of Transmission Durations

Although bandwidth-related statistics may be useful for classifying UAV manufacturers, they are insufficient to distinguish between specific models, as some models—particularly those from DJI—may use the same set of bandwidths. Therefore, further analysis of transmission durations is necessary. The durations were analyzed independently for each identified bandwidth of a particular UAV model. The corresponding histograms for the DJI Mini 2 are shown in

Figure 6. Once again, significant peaks are observed, corresponding to typical durations. In this case, a bin center is considered to represent a valid duration if the sum of its quantity and the quantities of the two neighboring bins on either side constitutes at least a two percent share of the observations corresponding to the given UAV and bandwidth.

To assess the accuracy of bandwidth and duration estimations, the root mean squared error (RMSE) was calculated as follows:

where

represents the estimated values and

is the true value of given parameter (bandwidth or duration). RMSE was computed individually for each bandwidth–duration pair. For bandwidth estimation, the minimum and maximum RMSE values are 28 kHz and 377 kHz, respectively, with a weighted average of 69 kHz. For duration estimation, RMSE values ranged from 16 μs to 349 μs, with a weighted average of 62 μs.

To validate the estimation, each considered duration value was verified by visually inspecting the spectrogram of a sample transmission corresponding to that value. For DJI models, the identification of all possible durations was confirmed to be accurate. However, this was not the case for Autel models due to their specific transmission scheme, in which packets are transmitted sequentially.

A series consists of a few (3–5) packets separated by short breaks. However, during these breaks, the transmitter is not deactivated; instead, it transmits a non-modulated carrier wave, as shown in the spectrograms in

Figure 7. This characteristic causes errors in duration estimation because a contour extracted from the spectrogram may correspond either to the edges of a single packet or to the combined edges of multiple packets. For example, for a single packet duration of 0.9 ms, estimated values of 1.9 ms, 2.9 ms, and 3.9 ms were sometimes returned—corresponding to 2, 3, and 4 packets (including breaks), respectively. This is illustrated in

Figure 8, where the first two transmissions were incorrectly detected as a single transmission. Nevertheless, valid results were returned an order of magnitude more frequently than erroneous ones.

For clarity of presentation, the occurrence rate of each duration for every UAV model and bandwidth is shown in

Supplementary Material. Instead, a summary of all identified bandwidth–duration pairs for each UAV model is provided in

Table 4 and

Table 5. In the case of DJI, there is a clear distinction between short, relatively narrowband transmissions and longer, wideband transmissions (9 MHz or more). The former are considered control or telemetry packets, while the latter carry video streams. Conversely, for Autel devices, transmission types are more difficult to differentiate. Generally, Autel packets are shorter than those of DJI but may be transmitted in series, as mentioned above. As before, it is assumed that transmissions with a bandwidth of at least 9 MHz carry video packets.

The inspection of the obtained results allows us to conclude that the combined statistics related to bandwidths and durations are sufficient for the classification of UAVs. It can be observed that none of the possible bandwidth–duration pairs are the same for any two UAV models from different manufacturers. Moreover, for each model, a specific feature has been identified that distinguishes it from all other models from the same brand. For DJI models, it was found that:

Mini 2 is the only device that utilizes a 1.2 MHz bandwidth,

Air 2S is the only device that transmits with [9 MHz, 0.6 s],

Mavic 3 is the only model that transmits with 36 MHz, along with [9 MHz, 1.1 ms],

Matrice 30 is the only model that does not transmit with a duration of 1.1 ms,

Matrice 300 is the only model that transmits with [9 MHz, 0.7 s], as well as with 2.2 MHz and 18 MHz.

For Autel models, the following features were identified:

Evo Nano is the only device that transmits with a 13.6 MHz bandwidth,

Evo Lite is the only device that transmits with 9 MHz, along with [1.2 MHz, 0.8 ms],

Evo II Pro is the only model that transmits with 18 MHz, along with [1.2 MHz, 0.8 ms].

3.3. Analysis of Frequency Hops

In addition to bandwidth and duration statistics, additional features are desired to enhance classification confidence. It was observed that the center frequency of transmissions is not constant. For short, narrowband packets, the frequency hops with each transmission, whereas for long, wideband packets, it changes less frequently. An investigation was conducted to determine whether the relative frequency offsets between hops exhibit regular patterns characteristic of specific UAV models.

This analysis was based on a subset of the original dataset, limited to transmissions longer than 1 ms and wider than 1 MHz. These restrictions were applied to filter the transmissions, retaining only those believed to contain video packets. In practice, it is known that such packets are transmitted by a UAV, whereas narrowband transmissions may originate from an RC, which is likely to be outside the detector’s range.

An example histogram of frequency hops is shown in

Figure 9. The highest peak occurs at 0 Hz, as video transmission is typically conducted at a constant carrier frequency most of the time. However, significant bars are also observed at non-zero frequencies, corresponding to typical frequency hops. Histograms were analyzed for each possible bandwidth–duration pair to determine the relationship between transmission parameters and the distribution of hops. It was found that frequency hops may vary with transmission bandwidth, while duration does not have a significant impact.

Table 6 presents the most frequent frequency hop values observed for each analyzed UAV. Cells marked with a “-” indicate that no transmissions with those parameters were captured for the given UAV in the 2.4 GHz band. Conversely, a cell marked with “N” indicates that no frequency hops were observed between consecutive transmissions.

It is evident that distinguishing between UAV models of the same brand is challenging because they use very similar frequency hopping parameters. An exception is the DJI Mini 2, which hops across 18 MHz-wide transmissions by ±8.4 MHz—this value differs from all other DJI drones. However, identical configurations are observed for the DJI Mini 2 and the Autel Evo II Pro, which may lead to misclassification if the classifier relies solely on bandwidth and hop values.

3.4. Classification Perfromance

To assess the performance of the proposed approach, a UAV classification model was implemented and evaluated. The classifier operates on a set of bandwidth and duration estimates obtained from a given number of detected transmissions. The distributions of these estimates are analyzed to identify clusters that constitute at least two percent of the observations. Each such cluster is assigned a corresponding bandwidth–duration pair. Next, the detected pairs are compared with the pairs identified for different UAV models (

Table 4 and

Table 5). The confidence metric for each UAV model is calculated as follows:

where

is the number of detected bandwidth–duration pairs that match the pairs identified for a given UAV model, and

is the total number of pairs for that UAV model. For example, consider an analyzed set of transmissions with two clusters corresponding to the bandwidth–duration pairs [1.2 MHz, 0.8 ms] and [9 MHz, 0.9 ms]. This results in a confidence of 1.0 for UAV 7 (2 of 2 pairs match), 0.5 for UAV 8 (1 of 2 pairs match), 0.14 for UAV 6 (1 of 7 pairs match), and 0.0 for all other UAV models. The predicted UAV model is the one with the highest confidence. Occasionally, the highest confidence level may be shared by more than one UAV model. In such cases, all these models are presented as the classifier’s output, as they are considered equally likely.

The performance of the classifier can be evaluated using the confusion matrix. This matrix illustrates the relationship between the actual classes (UAV models) and the classification predictions obtained from limited data sets. Three confusion matrices are provided, each corresponding to a different amount of data used for classification. A set of N (100, 300, or 1000) bandwidth–duration estimates was input to the classifier. The classification was repeated 10,000 times, each time with a different randomly selected set of estimates. The corresponding confusion matrices are shown in

Figure 10.

It is evident that there is no confusion between DJI and Autel UAVs. Moreover, over 95% accuracy in classification is observed for UAVs 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8. However, for UAV 8, many trials resulted in models 7 and 8 being equally likely. Additionally, UAV 3 was often misclassified as UAV 2, although accuracy improved significantly with an increased amount of input data. UAV 6 proved to be the most challenging to be classified correctly, as it was frequently mistaken for UAV 7, even with more input data. This difficulty arises because UAV 7 has only two identified bandwidth–duration pairs, one of which is shared with UAV 6. When this shared pair is detected in the input data, at least three other pairs must be matched for the confidence in UAV 6 to exceed that of UAV 7.

4. Discussion

The results presented in

Section 3 demonstrate that the statistical analysis of fundamental parameters related to RF transmissions—specifically bandwidths, durations, and center frequencies—can be useful for classifying UAVs. The analyzed parameters enable clear discrimination between different UAV brands and also allow for distinguishing models within the same brand when multiple parameters are combined for classification.

The distribution of frequency hops has been identified as a feature that may be unique to certain UAV models. However, this is not always the case, as multiple models have been found to follow hopping schemes with identical relative frequency offsets. Furthermore, beyond the analysis of video transmissions, it was observed that frequency hops in control packets exhibit an irregular distribution without significant peaks. The unpredictability of the hopping pattern in this context is likely a countermeasure against RF jamming. Consequently, the usefulness of such hopping distributions for UAV classification is questionable.

A visual examination of the obtained spectrograms reveals that UAV transmissions often include reference signals that create distinctive patterns on the time–frequency plane. Examples can be seen in

Figure 7b,c, where a window with muted frequency components appears in one of the packets near the center frequency. Similarly, many DJI transmissions contain symbols modulated with Zadoff–Chu sequences, producing diagonal lines or checkerboard-like patterns in the spectrogram. Classification confidence may be enhanced by integrating the recognition of these patterns with the approach proposed in this paper.

The results presented in

Section 3.4 demonstrate the strong overall performance of the proposed classification method. The values along the main diagonals of the confusion matrices are significantly higher than the off-diagonal values, and in most cases, they exceed 95%. However, for UAVs 6 and 7, a notable level of ambiguity is observed due to the sharing of some bandwidth–duration pairs. This similarity in RF transmissions from different sources is a common challenge, as also reported in other studies addressing the problem of UAV classification [

28,

30,

32].

5. Conclusions

In this paper, the author proposes a simple method for determining the UAV manufacturer and model based on the statistical analysis of parameters obtained through conventional time–frequency analysis of received RF signals. Another original aspect is the use of a set of low-complexity algorithms from the computer vision domain. These algorithms are applied to spectrograms to detect respective transmissions and estimate their basic parameters. It is demonstrated that the empirical distributions of packet durations, bandwidths, and frequency hops can be combined to distinguish between UAV models within the analyzed group.

The proposed method offers UAV classification accuracy comparable to that of methods described in the literature, as evidenced by the corresponding confusion matrices [

28,

30,

32,

33]. However, the superiority of the method presented in this paper lies in the fact that, unlike others, it is not based on CNNs. This means it does not require extensive training, nor does it need a high-performance processing unit to operate in real time. Consequently, it can be deployed on low-cost platforms such as single-board computers or Internet of Things (IoT) devices.

Although this research focuses on a limited set of UAV models, it is expected that unique features can be identified for other devices as well. To extend the scope to include more UAVs, it would be necessary to obtain a new dataset. While some datasets are publicly available, they contain data captured at lower sampling rates, which may affect the results because some transmissions could fall outside the recorded frequency band [

34,

35,

36,

37].

To further validate the proposed approach, evaluations should be conducted using transmissions captured under more realistic conditions than those inside an anechoic chamber. One initial method could involve simulating the wireless channel effects by introducing noise and fading to the original waveform samples. Alternatively, an SDR could be used to retransmit signals from the original waveforms, which can then be re-captured in real-world environments or passed through a wireless channel emulator. However, it is important to note that UAVs may perform spectrum sensing, meaning their transmissions are influenced by the presence of other signals in the ISM bands, such as WiFi or Bluetooth. This aspect cannot be replicated when retransmitting recorded waveforms. Therefore, the optimal approach is to record actual UAV transmissions in real-world environments.