Exploring the Potential of Lee Silverman Voice Treatment BIG for Improving Balance and Gait in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

Exclusion Criteria Included

- Atypical disease characteristics

- Previous participation in LSVT BIG

- Use of a duodopa pump or Deep Brain Stimulation

- Cognitive impairment or dementia affecting comprehension or ability to follow program instructions (Mini-Mental State Examination score ≤ 24) [46]

- Cardiovascular conditions limiting engagement in high-amplitude exercise.

2.3. Measurement Outcomes

2.3.1. Balance Assessments

2.3.2. Gait Assessments

2.4. Equipment Required

2.5. Assessors

2.6. Intervention

- Maximal Daily Exercises: Seven multidirectional, high-amplitude full-body exercises performed repetitively, with two in a seated position and five standing.

- Functional Component Tasks: Five functional activities, including a standard sit-to-stand task and four individualized exercises tailored to each patient’s daily life and goals, based on clinical evaluation.

- Hierarchy Tasks: One to three complex, multilevel tasks progressively increased in difficulty over the four-week program, customized to each patient’s real-life goals and interests.

- BIG Walking: Gait training emphasizing increased step length, arm swing, posture, and walking speed.

- Carryover Assignment: Activities assigned to patients to integrate BIG movements into real-world conditions.

- Homework: Daily independent practice of “Maximal Daily Exercises,” “Functional Component Tasks (sit-to-stand, reaching into a cupboard, turning in bed, fastening a button),” and “Hierarchy Tasks (cooking a full meal, dressing from start to finish, walking to store and back)” outside supervised sessions.

2.7. Experimental Procedure

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

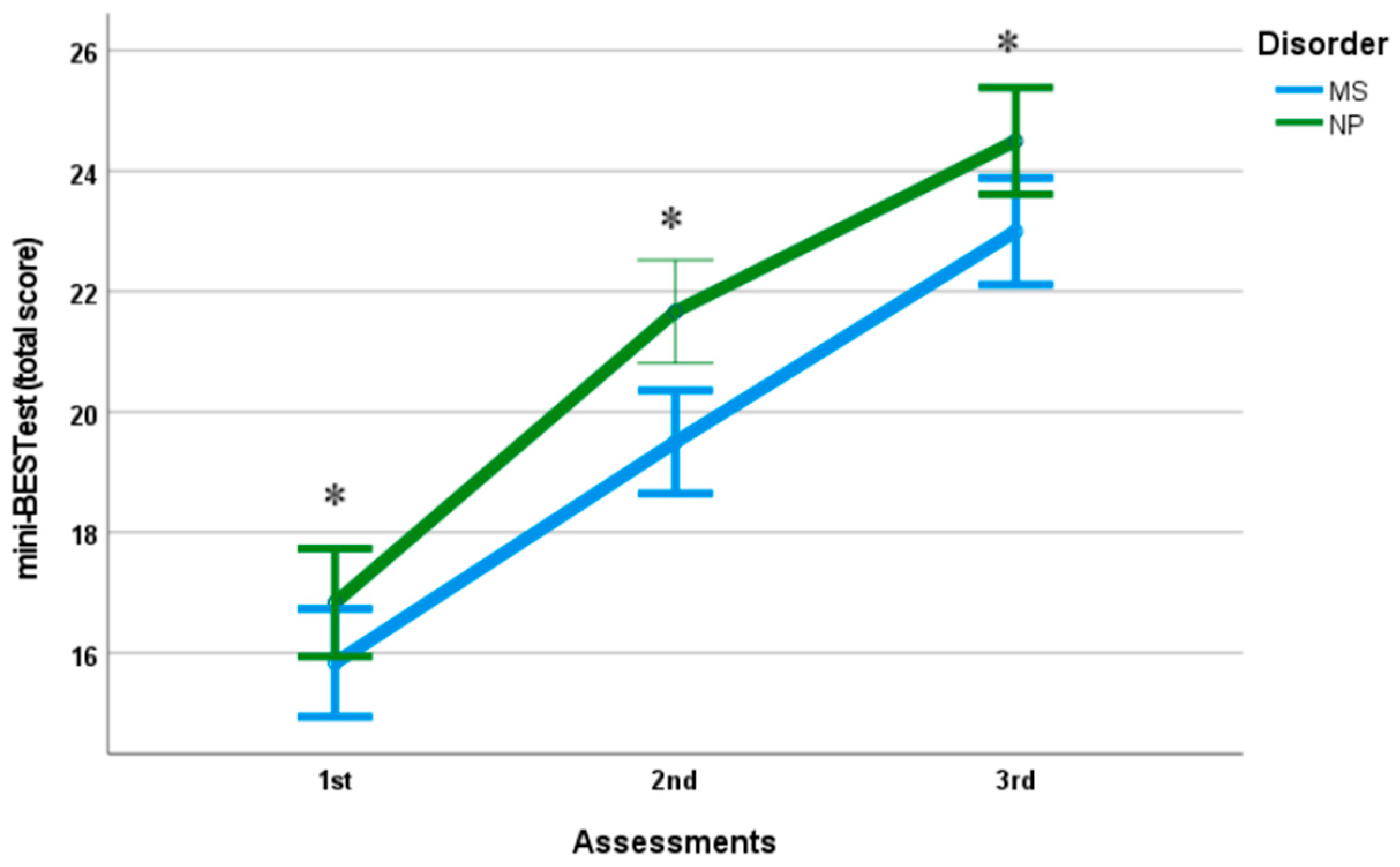

3.2. Balance

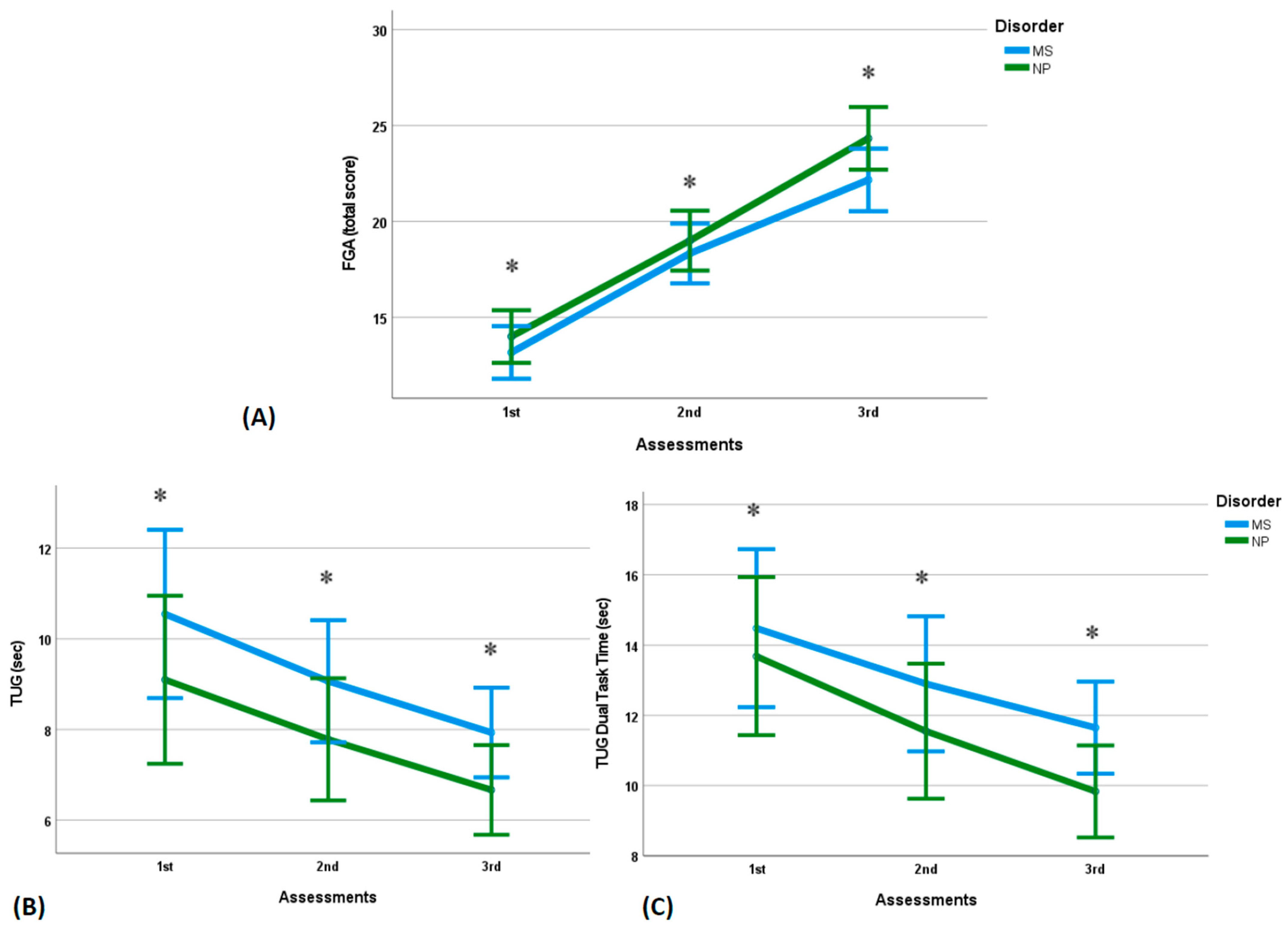

3.3. Gait Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ebersbach, G.; Ebersbach, A.; Edler, D.; Kaufhold, O.; Kusch, M.; Kupsch, A.; Wissel, J. Comparing exercise in Parkinson’s disease-the Berlin BIG Study. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 1902–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryans, L.A.; Palmer, A.D.; Anderson, S.; Schindler, J.; Graville, D.J. The Impact of Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT LOUD®) on Voice, Communication, and Participation: Findings from a Prospective, Longitudinal Study. J. Commun. Disord. 2020, 89, 106031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, T.; Huang, M.; Kong, X.; Wang, M.; Chen, X.; Feng, X.; Wie, C.; Wenig, X.; Xu, F. Lee Silverman Voice Treatment to improve speech in Parkinson’s disease: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Park. Dis. 2021, 2021, e3366870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.; Ebersbach, G.; Ramig, L.; Sapir, S. LSVT LOUD and LSVT BIG: Behavioral Treatment Programs for Speech and Body Movement in Parkinson Disease. Park. Dis. 2012, 2012, e391946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, B.G.; Fox, C.M.; Ramig, L.O.; McFarland, D.H. Intensive Amplitude-specific Therapeutic Approaches for Parkinson’s Disease. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 2008, 24, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterka, M.; Odorfer, T.; Schwab, M.; Volkmann, J.; Zeller, D. LSVT-BIG therapy in Parkinson’s disease: Physiological evidence for proprioceptive recalibration. BMC Neurol. 2020, 20, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konczak, J.; Krawczewski, K.; Tuite, P.; Maschke, M. The perception of passive motion in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 2007, 254, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, A.; Khan, N.; Defazio, G.; Rothwell, J.C.; Berardelli, A. Pathophysiology of somatosensory abnormalities in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 9, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuno, A.; Matsushima, A.; Saito, M.; Sakurai, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Yoshiki, S. Quantitative assessment of the gait improvement effect of LSVT BIG® using a wearable sensor in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, J.; Malfroid, K.; Nyffeler, T.; Bohlhalter, S.; Vanbellingen, T. Application of LSVT BIG Intervention to Address Gait, Balance, Bed Mobility, and Dexterity in People with Parkinson Disease: A Case Series. Phys. Ther. 2014, 94, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkin, C. LSVT®BIG Exercise-Induced Neuroplasticity in People with Parkinson’s Disease: An Assessment of Physiological and Behavioral Outcomes. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI, USA, 2020. ProQuest Number: 27741888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, M.W.; O’Callaghan, B.P.F.; Diamond, P.; Liegey, J.; Hughes, G.; Lowery, M.M. Quantitative clinical assessment of motor function during and following LSVT-BIG® therapy. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2020, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucet, B.M.; Blanchard, M.; Franc, I. Effects of LSVT BIG® on Bradykinesia During Activities of Daily Living. OTJR Occup. Ther. J. Res. 2025, 15394492251367275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaghiani, Z.; Tahan, N.; Ganjeh, S.; Baghban, A.A.; Khoshdel, A.; Shoeibi, A. Evaluating the Impact of Adding Lee Silverman Voice Treatment BIG into Routine Physiotherapy on Both Motor and Nonmotor Functions in Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease. Dubai Med. J. 2025, 8, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, M.N.; Rischbieth, B.; Schammer, T.T.; Seaforth, C.; Shaw, A.J.; Phillips, A.C. Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT)-BIG to improve motor function in people with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 32, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.Y.; Oh, H.M.; Bok, S.K.; Chang, W.H.; Choi, Y.; Chun, M.H.; Han, S.J.; Han, T.R.; Jee, S.; Jung, S.H.; et al. KSNR Clinical Consensus Statements: Rehabilitation of Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Neurorehabil. 2020, 13, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarci, O.; Wingerchuk, D. Epidemiology and natural history of multiple sclerosis: New insights. Cur. Opin. Neurol. 2006, 19, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amatya, B.; Khan, F.; Galea, M. Rehabilitation for people with multiple sclerosis: An overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019, 14, CD012732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelleher, K.J.; Spence, W.; Solomonidis, S.; Apatsidis, D. The characterisation of gait patterns of people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2010, 32, 1242–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, S.; Khan, F.; Kesselring, J. Rehabilitation interventions in multiple sclerosis: An overview. J. Neurol. 2012, 259, 1994–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barin, L.; Salmen, A.; Disanto, G.; Babačić, H.; Calabrese, P.; Chan, A.; Kamm, C.P.; Kesselring, J.; Kuhle, J.; Gobbi, C.; et al. The disease burden of Multiple Sclerosis from the individual and population perspective: Which symptoms matter most? Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2018, 25, 12–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, F.; Rochester, L.; Paul, L.; Rafferty, D.; O’Leary, C.; Evans, J. Walking and talking: An investigation of cognitive—Motor dual tasking in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2009, 15, 1215–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkul, C.; Eldemir, K.; Yildirim, M.S.; Cobanoglu, G.; Eldemir, S.; Guzel, N.A.; Irkec, C.; Guclu-Gunduz, A. Relationship between sensation and balance and gait in multiple sclerosis patients with mild disability. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 87, 105690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fling, B.W.; Dutta, G.G.; Schlueter, H.; Cameron, M.H.; Horak, F.B. Associations between Proprioceptive Neural Pathway Structural Connectivity and Balance in People with Multiple Sclerosis. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, M.; Munari, D.; Geroin, C.; Gajofatto, A.; Benedetti, M.D.; Midiri, A.; Carla, F.; Picelli, A.; Waldner, A.; Smania, N. Sensory integration balance training in patients with multiple sclerosis: A randomized, controlled trial. Mult. Scler. 2015, 21, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L.J.; McCoy, S.C.; Castellano, V.; Gutierrez, G.; Stevens, J.E.; Walter, G.A.; Vandenborne, K. Resistance training improves strength and functional capacity in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2004, 10, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, A.E.G. Exercise in Multiple Sclerosis. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 24, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feltham, M.G.; Collett, J.; Izadi, H.; Wade, D.T.; Morris, M.G.; Meaney, A.J.; Howells, K.; Sackley, C.; Dawes, H. Cardiovascular adaptation in people with multiple sclerosis following a twelve week exercise programme suggest deconditioning rather than autonomic dysfunction caused by the disease. Results from a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 49, 765–774. [Google Scholar]

- Halabchi, F.; Alizadeh, Z.; Sahraian, M.A.; Abolhasani, M. Exercise prescription for patients with multiple sclerosis; potential benefits and practical recommendations. BMC Neurol. 2017, 17, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duff, W.R.D.; Andrushko, J.W.; Renshaw, D.W.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Farthing, J.P.; Danielson, J.; Evans, C.D. Impact of Pilates Exercise in Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. MS Care 2018, 20, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalron, A.; Rosenblum, U.; Frid, L.; Achiron, A. Pilates exercise training vs. physical therapy for improving walking and balance in people with multiple sclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2016, 31, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soysal Tomruk, M.; Zu, M.Z.; Kara, B.; İdiman, E. Effects of Pilates exercises on sensory interaction, postural control and fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2016, 7, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alphonsus, K.B.; Su, Y.; D’Arcy, C. The effect of exercise, yoga and physiotherapy on the quality of life of people with multiple sclerosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther. Med. 2019, 43, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.; Taylor-Piliae, R.E. The effects of Tai Chi on physical and psychosocial function among persons with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Med. 2017, 31, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Jing, Y.; Li, Y.; Lian, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Z. Rehabilitation treatment of multiple sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1168821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldanzi, C.; Crispiatico, V.; Foresti, S.; Groppo, E.; Rovaris, M.; Cattaneo, D.; Vitali, C. Effects of Intensive Voice Treatment (The Lee Silverman Voice Treatment [LSVT LOUD]) in Subjects With Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study. J. Voice 2022, 36, 585.e1–585.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, V.; Egan, M.; Sauvé-Schenk, K. LSVT BIG in late stroke rehabilitation: A single-case experimental design study. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 86, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffitt, R.M.; Henderson, W.; Scholl, S.; Nettleton, M. Lee Silverman Voice Treatment BIG® for a Person With Stroke. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 72, 7205210010p1–7205210010p6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffitt, R.; Henderson, W.; Stupps, M.; Binder, L.; Irlmeier, B.; Knapp, E. Feasibility of the Lee Silverman voice treatment-BIG intervention in stroke. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2021, 41, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Lancaster, G.A.; Campbell, M.J.; Thabane, L.; Hopewell, S.; Coleman, C.L.; Bond, C.M. Defining Feasibility and Pilot Studies in Preparation for Randomised Controlled Trials: Development of a Conceptual Framework. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Kotob, R.; Giangregorio, L.M. Pilot and feasibility studies in exercise, physical activity, or rehabilitation research. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018, 4, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, C.G.; Poewe, W.; Rascol, O.; Sampaio, C.; Stebbins, G.T.; Counsell, C.; Giladi, N.; Holloway, R.G.; Moore, C.G.; Wenning, G.K.; et al. Movement Disorder Society Task Force on Rating Scales for Parkinson’s Disease. Movement Disorder Society Task Force report on the Hoehn and Yahr staging scale: Status and recommendations. Mov. Disord. 2004, 19, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motl, R.; Neal, W.; Backus, D.; Hebert, J.; McCully, K.; Bethoux, F.; Plummer, P.; Ng, A.; Lowman, J.; Schmidt, H.; et al. Middle-range scores from the patient determined disease steps scale reflect varying levels of walking dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2024, 24, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, L.K.R.; Scianni, A.A.; Lima, L.O.; de Carvalho Lana, R.; Rodrigues-De-Paula, F. The Mini-BESTest is an independent predictor of falls in Parkinson Disease. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2020, 24, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallin, A.; Kierkegaard, M.; Franzén, E.; Johansson, S. Test-Retest Reliability of the Mini-BESTest in People with Mild to Moderate Multiple Sclerosis. Phys. Ther. 2021, 101, pzab045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorenzato, E.; Cauzzo, S.; Weis, L.; Garon, M.; Pistonesi, F.; Cianci, V.; Nasi, L.M.; Vianello, F.; Zecchinelli, L.A.; Pezzoli, G.; et al. Optimal MMSE and MoCA cutoffs for cognitive diagnoses in Parkinson’s disease: A data-driven decision tree model. J. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 466, 123283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchignoni, F.; Horak, F.; Godi, M.; Nardone, A.; Giordano, A. Using psychometric techniques to improve the Balance Evaluation Systems Test: The mini-BESTest. J. Rehabil. Med. 2010, 42, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulou, S.I.; Billis, E.; Gedikoglou, I.A.; Michailidou, C.; Nowicky, A.V.; Skrinou, D.; Michailidi, F.; Chandrinou, D.; Meligkoni, M. Reliability, validity and minimal detectable change of the Mini-BESTest in Greek participants with chronic stroke. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2019, 35, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, J.V.; Horak, F.B.; Tran, V.K.; Nutt, J.G. Multiple balance tests improve the assessment of postural stability in subjects with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006, 77, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrisley, D.M.; Marchetti, G.F.; Kuharsky, D.K.; Whitney, S.L. Reliability, internal consistency, and validity of data obtained with the functional gait assessment. Phys. Ther. 2004, 84, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulou, S.; Kellari, A.; Gedikoglou, I.A.; Kozonaki, D.G.; Nika, P.; Sakellari, V. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Psychometric Characteristics of the Greek Functional Gait Assessment Scale in Healthy Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchet, O.; Fantino, B.; Allali, G.; Muir, S.W.; Montero-Odasso, M.; Annweiler, C. Timed Up and Go test and risk of falls in older adults: A systematic review. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2011, 15, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, E.; Galvin, R.; Keogh, C.; Horgan, F.; Fahey, T. Is the Timed Up and Go test a useful predictor of risk of falls in community dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahya, M.; Moon, S.; Ranchet, M.; Vukas, R.R.; Lyons, E.K.; Pahwa, R.; Akinwuntan, A.; Devos, H. Brain activity during dual task gait and balance in aging and age-related neurodegenerative conditions: A systematic review. Exp. Gerontol. 2019, 128, 110756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. How to Understand the 95% Confidence Interval Around the Relative Risk, Odds Ratio, and Hazard Ratio: As Simple as It Gets. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2023, 84, 23f14933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacson, S.; O’Brien, A.; Lazaro, J.D.; Ray, A.; Fluet, G. The JFK BIG study: The impact of LSVT BIG® on dual task walking and mobility in persons with Parkinson’s disease. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2018, 30, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishel, S.C.; Hotchkiss, M.E.; Brown, S.A. The impact of LSVT BIG therapy on postural control for individuals with Parkinson disease: A case series. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2020, 36, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna, G.; Pardo-Cocuy, L.F.; Garzón, A.; Benítez, A.; Parada-Gereda, H.M. Effectiveness of Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT®BIG) for improving motor function in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 104, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissoneault, C.; Datta, S.; Rose, D.K.; Waters, M.J.; Khanna, A.; Daly, J.J. Innovative Long-Dose Neurorehabilitation for Balance and Mobility in Chronic Stroke: A Preliminary Case Series. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrini, C.; Gervasoni, E.; Perini, G.; Cosentino, C.; Putzolu, M.; Montesano, A.; Pelosin, E.; Prosperini, L.; Cattaneo, D. Mobility and balance rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2023, 69, 104424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemková, E.; Hamar, D. The Effect of Task-Oriented Sensorimotor Exercise on Visual Feedback Control of Body Position and Body Balance. Hum. Mov. 2010, 11, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, S.H.; Ilbeigi, S.; Ahmadi, M.M.; Yousefi, M.; Mousavi-Mirzaei, M. Comparative effects of sensory motor and virtual reality interventions to improve gait, balance and quality of life MS patients. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzinger, G.M.; Fisher, B.E.; McEwen, S.; Beeler, J.A.; Walsh, J.P.; Jakowec, M.W. Exercise-enhanced neuroplasticity targeting motor and cognitive circuitry in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházková, M.; Tintera, J.; Špaňhelová, S.; Prokopiusova, T.; Rydlo, J.; Pavlikova, M.; Prochazka, A.; Rasova, K. Brain activity changes following neuroproprioceptive “facilitation, inhibition” physiotherapy in multiple sclerosis: A parallel group randomized comparison of two approaches. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 57, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavazzi, E.; Cazzoli, M.; Pirastru, A.; Blasi, V.; Rovaris, M.; Bergsland, N.; Baglio, F. Neuroplasticity and Motor Rehabilitation in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review on MRI Markers of Functional and Structural Changes. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 707675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straudi, S.; Martinuzzi, C.; Pavarelli, C.; Sabbagh Charabati, A.; Benedetti, M.G.; Foti, C.; Bonato, M.; Zancato, E.; Basaglia, N. A task-oriented circuit training in multiple sclerosis: A feasibility study. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, H.M.; Shalaby, M.N.; Ali, S.A.; Soubhy, Z.H. Effect of Task Oriented Approach on Balance in Ataxic Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Med. J. Cairo Univ. 2019, 87, 4789–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmani, S.; Mousavi, S.H.; Navardi, S.; Hosseinzadeh, F.; Pashaeypoor, S. The barriers and facilitators to health-promoting lifestyle behaviors among people with multiple sclerosis during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A content analysis study. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombard, Y.; Baker, G.R.; Orlando, E.; Fancott, C.; Bhatia, P.; Casalino, S.; Onate, K.; Denis, J.L.; Pomey, M.P. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddocks, M.; Fettes, L.; Takemura, N.; Bayly, J.; Talbot-Rice, H.; Turner, K.; Tiberini, R.; Harding, R.; Murtagh, E.M.F.; Siegert, R.J.; et al. Functional goals and outcomes of rehabilitation within palliative care: A multicentre prospective cohort study. BMC Palliat. Care 2025, 24, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouça-Machado, R.; Rosário, A.; Caldeira, D.; Castro Caldas, A.; Guerreiro, D.; Venturelli, M.; Tinazzi, M.; Schena, F.; Ferreira, J. Physical Activity, Exercise, and Physiotherapy in Parkinson’s Disease: Defining the Concepts. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2019, 7, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; He, Y.; He, M. The comprehensive impact of exercise interventions on cognitive function and quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paltamaa, J.; Sjögren, T.; Peurala, S.; Heinonen, A. Effects of physiotherapy interventions on balance in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Rehabil. Med. 2012, 44, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snook, E.M.; Motl, R.W. Effect of Exercise Training on Walking Mobility in Multiple Sclerosis: A Meta-Analysis. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 2008, 23, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Yang, Y.R.; Tsai, Y.A.; Wang, R.Y. Cognitive and motor dual task gait training improve dual task gait performance after stroke—A randomized controlled pilot trial. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, L.; Peterson, E.; O’Malley, N.; Galvin, R.; Finlayson, M.; Coote, S. Development of the Better Balance Program for People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Complex Fall-Prevention Intervention. Int. J. MS Care 2021, 23, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | MS. 2 Group Mean (SD) 1 | PD 3 Group Mean (SD) 1 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N 4 | 6 | 6 | NA 9 |

| Sex (W:M) 5 | 5W:1M | 6M | NA |

| Age | 45 ± 8 | 68 ± 3 | NA |

| Mini-BESTest 6 | 15.83 ± 0.98 | 16.83 ± 0.98 | p > 0.05 |

| FGA 7 | 13.2 ± 1.6 | 14 ± 1.4 | p > 0.05 |

| TUG 8 | 10.5 ± 2.7 | 9.1 ± 0.9 | p > 0.05 |

| Variables | MS. 2 Group—Mean (SD) 1—[95% CI] | PD 3 Group—Mean (SD) 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Ass 4 | 2nd Ass | 3rd Ass | 1st Ass | 2nd Ass | 3rd Ass | |

| mini-BESTest 5 (from total score/28) | 15.83 (0.98) [15.046–16.614] | 19.50 (0.84) * [18.8, 20.2] | 23.00 (0.89) * [22.3, 23.7] | 16.83 (0.98) [16, 17.6] | 21.67 (1.03) * [20.8, 22.5] | 24.50 (1.05) * [23.7, 25.3] |

| R leg standing time (sec) | 9.02 (4.68) [5.28, 12.8] | 13.50 (5.04) * [9.47, 17.5] | 15.80 (4.54) * [12.2, 19.4] | 14.53 (3.46) [11.8, 17.3] | 18.05 (1.94) * [16.5, 19.6] | 19.20 (1.49) * [18, 20.4 |

| L leg standing time (sec) | 9.32 (3.40) * [6.6, 12] | 15.38 (3.16) * [12.9, 17.9] | 18.55 (2.09) * [16.9, 20.2] | 14.00 (2.54) [11.3, 16.7] | 18.33 (1.55) * [17.1, 19.6] | 19.35 (1.09) * [18.5, 20.2] |

| Foam standing time (sec) | 11.82 (4.11) * [8.53, 15.1] | 17.50 (5.27) * [13.3, 21.7] | 21.38 (4.94) * [17.4, 25.3] | 19.37 (2.87) * [17.1, 21.7] | 26.43 (2.27) * [24.6, 28.3] | 29.43 (0.91) * [28.7, 30.2] |

| Incline Standing Time (sec) | 21.18 (2.65) * [19.1, 23.3] | 29.07 (1.76) * [27.7, 30.5] | 30.00 (0.00) * [30, 30] | 25.27 (3.75) * [22.3, 28.3] | 30.00 (0.00) * [30, 30] | 30.00 (0.00) * [30, 30] |

| FGA 6 (from total score/30) | 13.17 (1.60) [11.9, 14.4] | 18.33 (2.34) * [16.5, 20.2] | 22.17 (2.04) * [20.5, 23.8] | 14.00 (1.41) [12.9, 15.1] | 19.00 (0.63) * [18.5, 19.5] | 24.33 (1.50) * [23.1, 25.5] |

| TUG (sec) | 10.55 (2.73) [8.37, 12.7] | 9.07 (1.76) * [7.66, 10.5] | 7.93 (1.49) * [6.74, 9.12] | 9.10 (0.92) [8.36, 9.84] | 7.78 (1.14) * [6.87, 8.69] | 6.66 (0.37) * [6.36, 6.96] |

| Variables | Group | N 1 | Mean Difference ± SD 2, [95% CI] | Leven’s Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miniBEST 3 | MS 4 | 6 | 7.17 ± 0.98, [6.39, 7.95] | t(9.976) = −0.859, p > 0.05 |

| NP 5 | 6 | 7.67 ± 1.03, [6.85, 8.49] | ||

| TUG 6 | MS | 6 | 2.617 ± 1.60, [1.34, 3.9] | t(7.200) = 0.253, p > 0.05 |

| NP | 6 | 2.433 ± 0.77, [1.82, 3.05] | ||

| TUGdual 7 | MS | 6 | 2.833 ± 2.00, [1.23, 4.43] | t(9.337) = 0.986, p > 0.05 |

| NP | 6 | 3.850 ± 1.53, [2.63, 5.07] | ||

| FGA 8 | MS | 6 | 9.00 ± 1.26, [7.99, 10] | t(8.805) = −1.451, p > 0.05 |

| NP | 6 | 10.33 ± 1.86, [8.84, 11.8] | ||

| Foam 9 | MS | 6 | 9.577 ± 1.33, [8.52, 10.6] | t(7.902) = −0.451, p > 0.05 |

| NP | 6 | 10.067 ± 2.36, [8.18, 12] | ||

| Incline 10 | MS | 6 | 8.817 ± 2.64, [6.71, 10.9] | t(8.988) = 2.178, p > 0.05 |

| NP | 6 | 4.733 ± 3.75, [1.73, 7.73] | ||

| RLegStand 11 | MS | 6 | 6.783 ± 3.24, [4.19, 9.37] | t(9.351) = 1.270, p > 0.05 |

| NP | 6 | 4.667 ± 2.47, [2.69, 6.65] | ||

| LLegStand 12 | MS | 6 | 9.233 ± 2.19, [7.48, 11] | t(9.498) = 3.411, p = 0.007 |

| NP | 6 | 5.35 ± 1.73, [3.97, 6.73] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aloupis, K.; Bania, T.; Trachani, E.; Tsepis, E.; Gotsopoulou, A.; Lampropoulou, S. Exploring the Potential of Lee Silverman Voice Treatment BIG for Improving Balance and Gait in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010484

Aloupis K, Bania T, Trachani E, Tsepis E, Gotsopoulou A, Lampropoulou S. Exploring the Potential of Lee Silverman Voice Treatment BIG for Improving Balance and Gait in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):484. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010484

Chicago/Turabian StyleAloupis, Konstantinos, Theofani Bania, Eftychia Trachani, Elias Tsepis, Antigoni Gotsopoulou, and Sofia Lampropoulou. 2026. "Exploring the Potential of Lee Silverman Voice Treatment BIG for Improving Balance and Gait in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010484

APA StyleAloupis, K., Bania, T., Trachani, E., Tsepis, E., Gotsopoulou, A., & Lampropoulou, S. (2026). Exploring the Potential of Lee Silverman Voice Treatment BIG for Improving Balance and Gait in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010484