Towards Intelligent Manufacturing: Machine Learning, Deep Learning, and Computer Vision for Tool Wear Estimation in Milling and Micromilling Processes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Questions Formulation and Keyword Selection

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Quality Evaluation Criteria

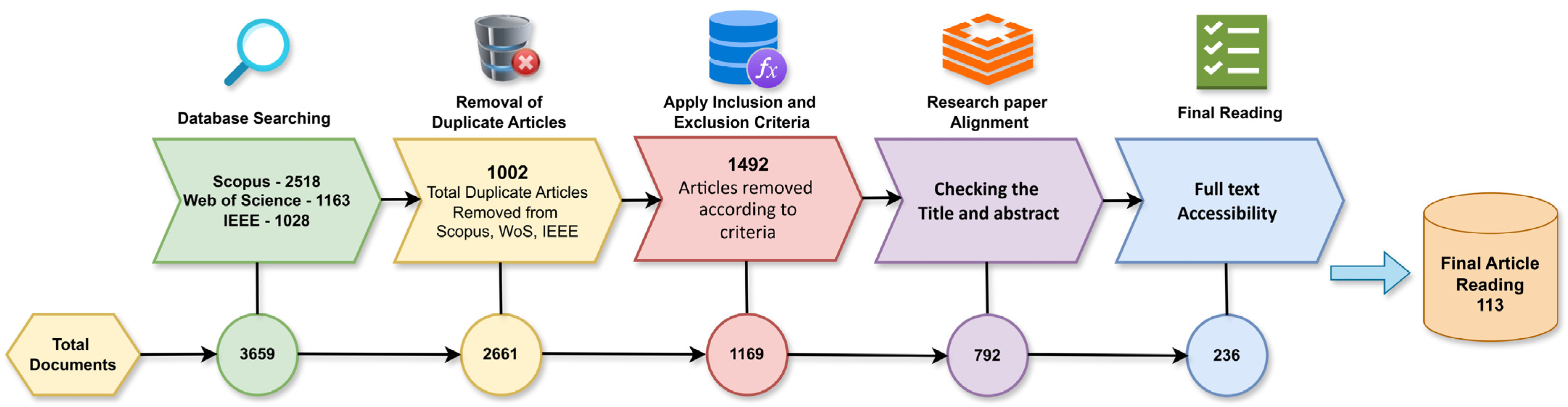

2.4. PRISMA Implementation

3. Background Study

3.1. Milling and Micromilling Process

3.2. Types of Wear

4. Role of Predictive Maintenance

4.1. Fundamentals of Predictive Maintenance

- (a)

- Corrective Maintenance

- (b)

- Preventive Maintenance

- (c)

- Predictive Maintenance

- (d)

- Prescriptive Maintenance

4.2. Predictive Maintenance in the Machining Process

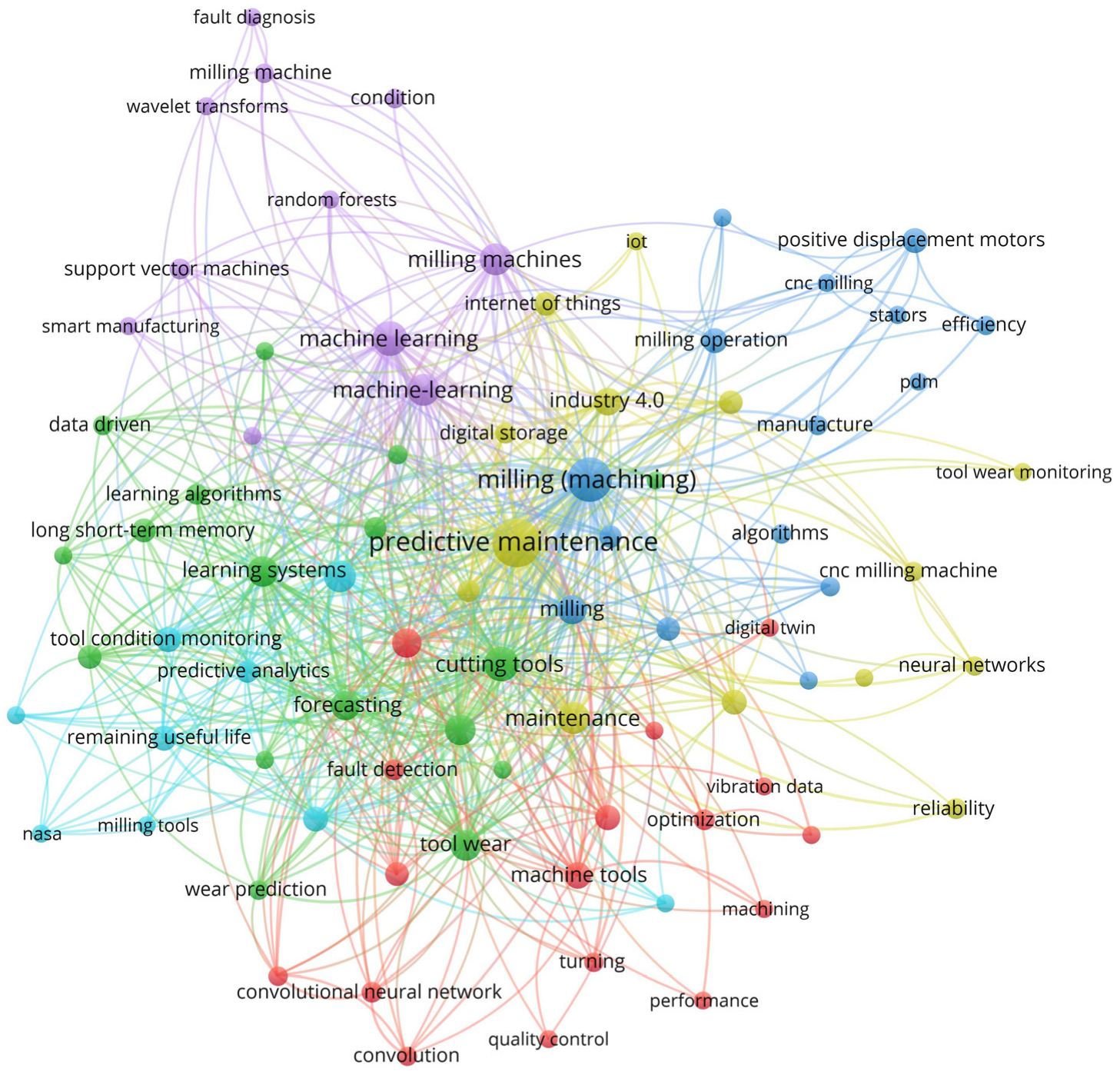

5. Approaches Used in Predictive Maintenance

5.1. Knowledge-Based System

5.2. Physics-Based Model

5.3. Data-Driven Model

6. Data-Driven Model Used in Milling and Micromilling

6.1. Sensors

6.1.1. Accelerometer Sensor

6.1.2. Acoustic Emission Sensor

6.1.3. Current Sensor

6.1.4. Dynamometer

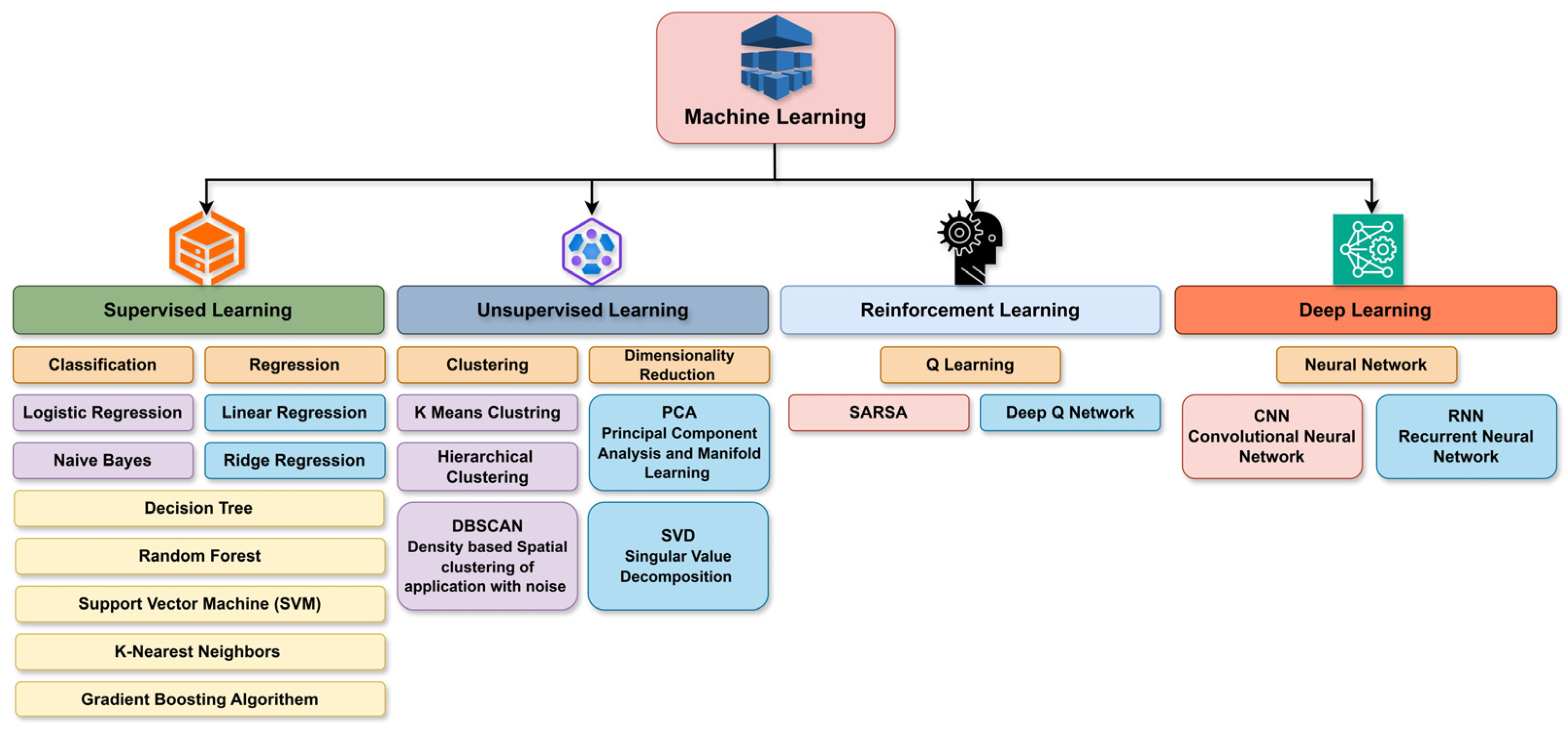

6.2. Machine Learning Model

6.3. Deep Learning Model

6.4. Computer Vision Approach

7. Recent Advancement

7.1. Reinforcement Learning Model

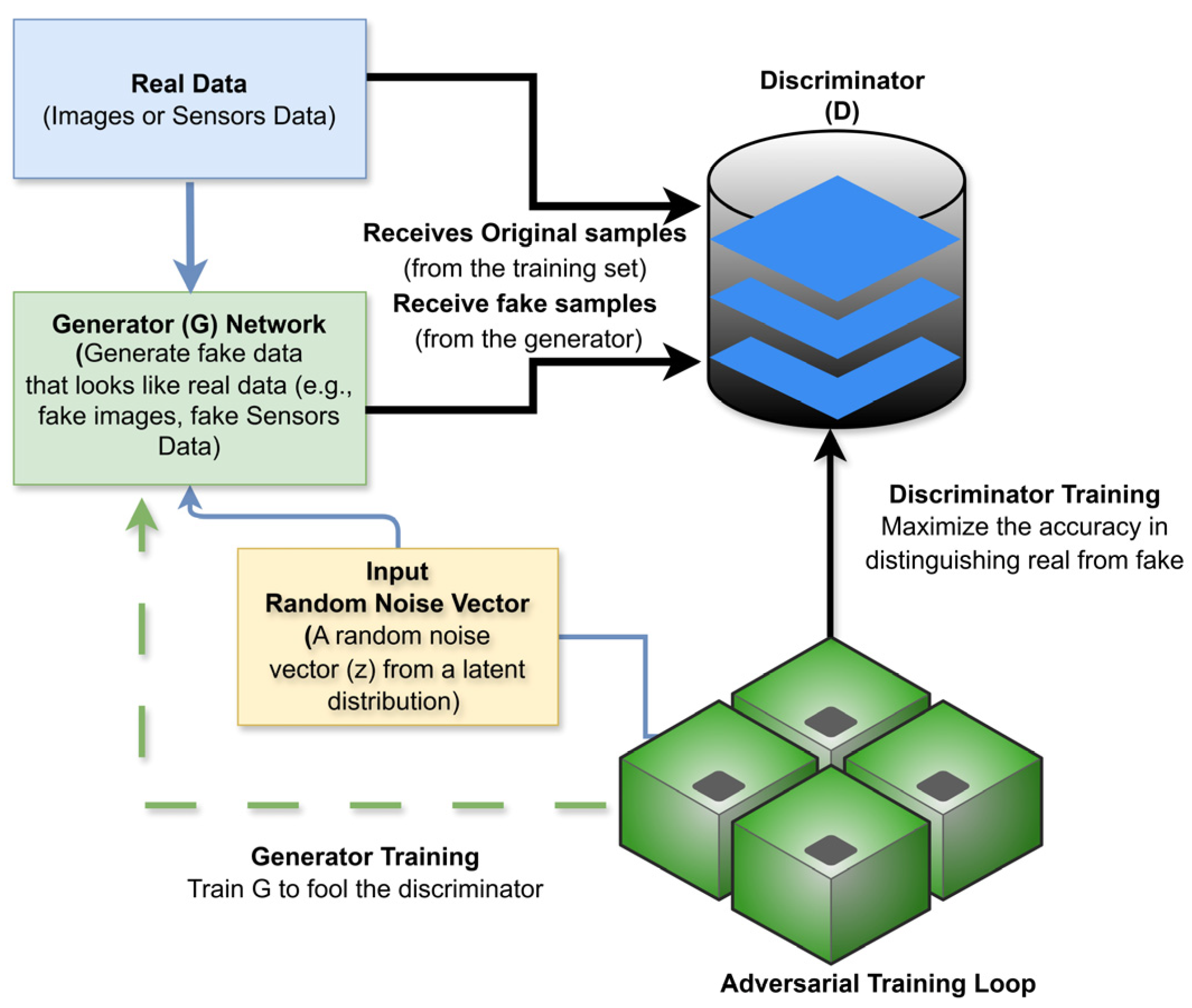

7.2. Generative Adversarial Network

7.3. Transfer Learning

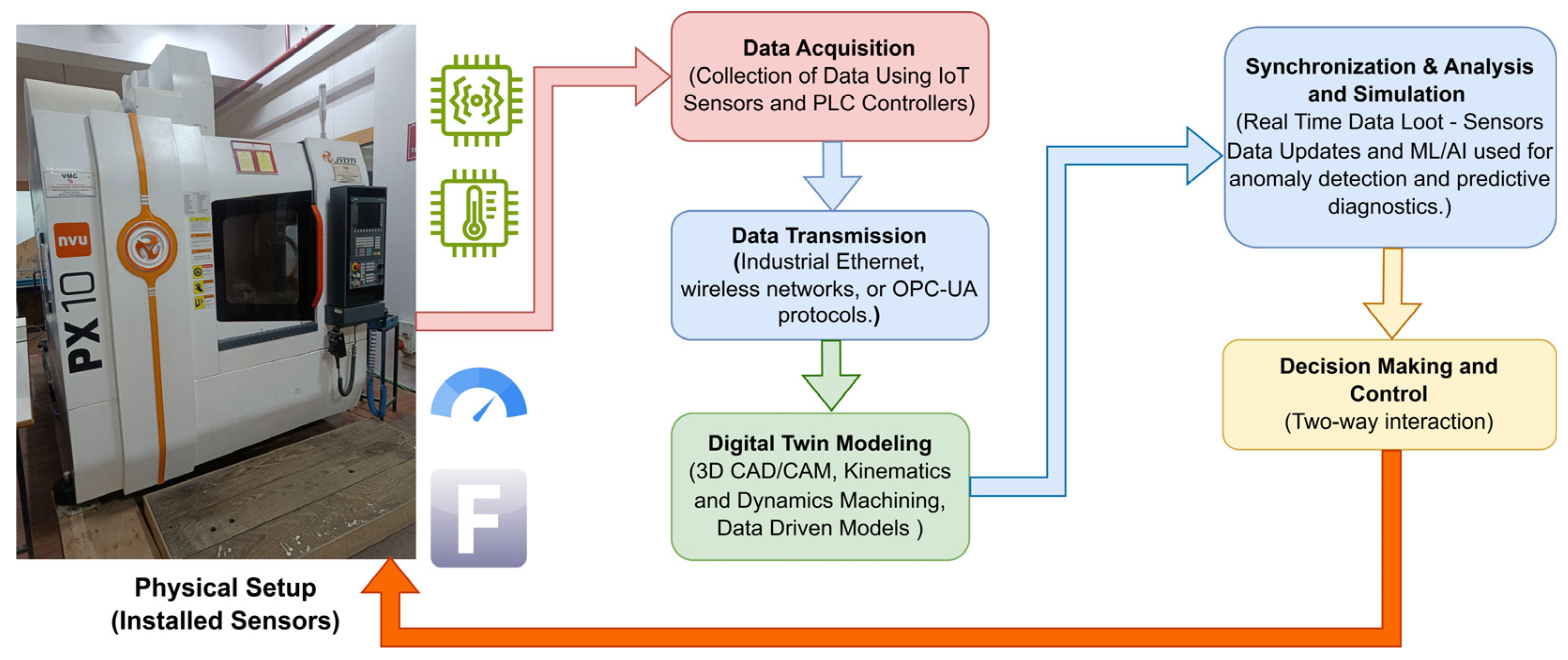

7.4. Digital Twin

7.5. Explainable AI (XAI)

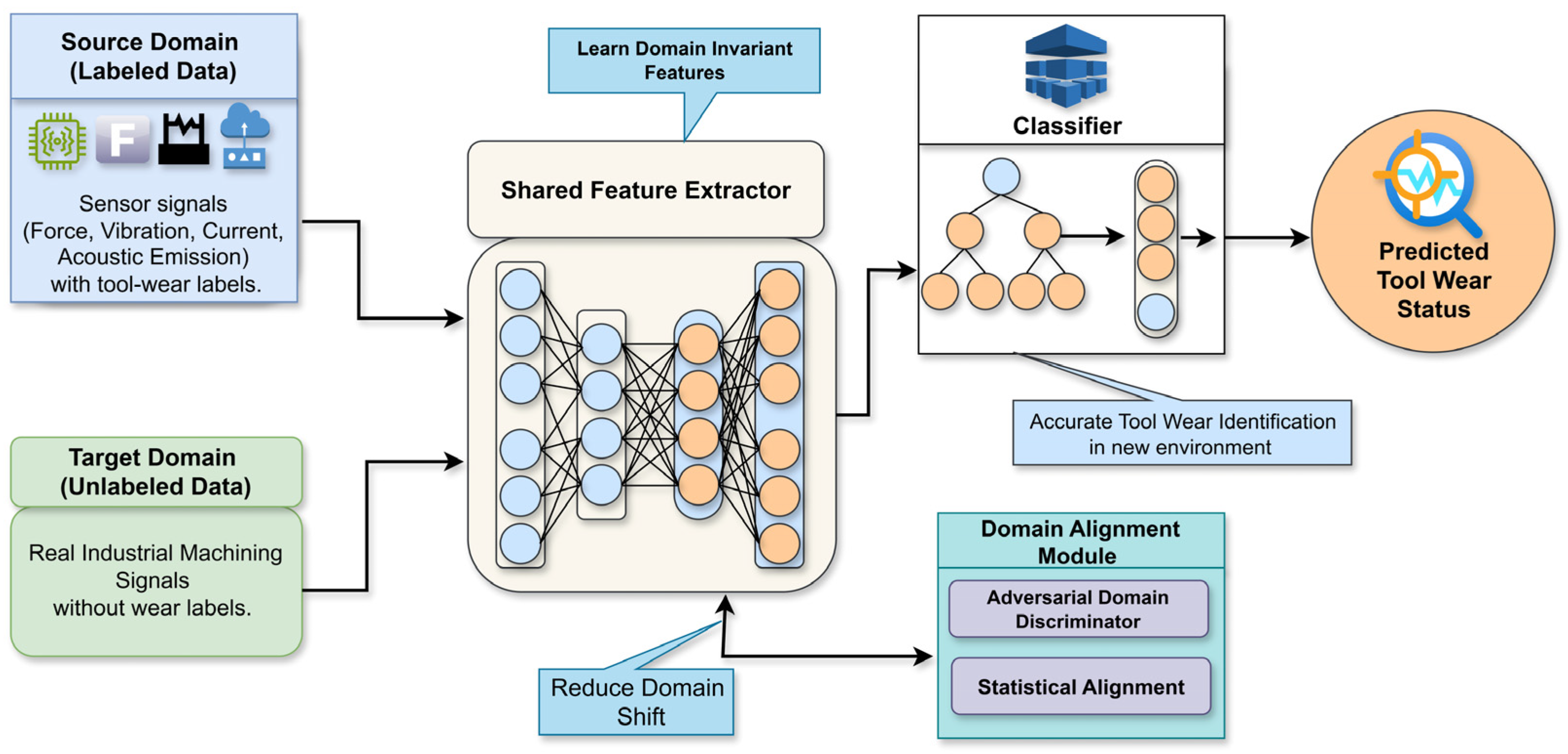

7.6. Domain Adaptation

7.7. Multi-Modal Fusion

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AE | Acoustic Emission |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| BPNN | Back Propagation Neural Network |

| CWT | Continuous Wavelet Transform |

| CCD | Charge-Coupled Device |

| CNC | Computer Numerical Control |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| EDoF | Extended Depth of Field |

| FFBP | Feed Forward Back Propagation |

| FFNN | Feed Forward Neural Network |

| GAN | Generative adversarial network |

| GBR | Gradient Boosting Regressor |

| Grad-CAM | Gradient-Weighted Class Activation Mapping |

| HMM | Hidden Markov Model |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| KPCA_IRBF | Kernel Principal Component Analysis with an Integrated Radial Basis Function |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLP | Multi-layer Perceptron |

| MQL | Minimum Quantity Lubrication |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| NF-MQL | Nano Fluid Minimum Quantity Lubrication |

| PdM | Predictive Maintenance |

| PEM | Proton Exchange Membrane |

| PIOC | Population–Intervention–Outcome–Context |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| ResNet | Residual Network |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RQ | Research Question |

| RUL | Remaining Useful Life |

| RVM | Relevance Vector Machine |

| SARSA | State-Action-Reward-State-Action |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| SCNN-Ex | Statistical Convolutional Neural Network Extension |

| SHAP | Shapley Additive Explanations |

| SVG | Support Vector Gradient |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| TCN–LSTM | Temporal Convolutional Network–Long Short-Term Memory |

| VMD | Variational Mode Decomposition |

| TFMTF | Time-Frequency Markov Transition Field |

| XAI | Explainable AI |

| XGB | Extreme Gradient and Boosting |

References

- Johansson, D.; Lindvall, R.; Windmark, C.; M’sAoubi, R.; Can, A.; Bushlya, V.; Ståhl, J.-E. Assessment of metal cutting tools using cost performance ratio and tool life analyses. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 38, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gackowiec, P. General overview of maintenance strategies—Concepts and approaches. Multidiscip. Asp. Prod. Eng. 2019, 2, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bona, G.; Cesarotti, V.; Arcese, G.; Gallo, T. Implementation of Industry 4.0 technology: New opportunities and challenges for maintenance strategy. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 180, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, K.; Sung, S.; Park, D. Prediction of the CNC tool wear using the machine learning technique. In Proceedings of the 6th Annual Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence, CSCI 2019, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 5–7 December 2019; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warke, V.; Kumar, S.; Bongale, A.; Kamat, P.; Kotecha, K.; Selvachandran, G.; Abraham, A. Improving the useful life of tools using active vibration control through data-driven approaches: A systematic literature review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 128, 107367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA Transparent Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. 2018. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Gao, S.; Duan, X.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, Y. Generic Cutting Force Modeling with Comprehensively Considering Tool Edge Radius, Tool Flank Wear and Tool Runout in Micro-End Milling. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ercetin, A.; Aslantaş, K.; Özgün, Ö.; Perçin, M.; Chandrashekarappa, M.P.G. Optimization of Machining Parameters to Minimize Cutting Forces and Surface Roughness in Micro-Milling of Mg13Sn Alloy. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.K. Influence of Microphone Tilt Angle on Instability Identification in Micromilling of Thin-walled Ti6Al4V. Manuf. Lett. 2023, 35, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, D.; Choong, Z.J.; Shi, Y.; Hedley, J.; Zhao, Y. Diamond micro-milling of lithium niobate for sensing applications. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2016, 26, 095005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeni, A.; Metelli, A.; Cappellini, C.; Attanasio, A. Experimental optimization of process parameters in CuNi18Zn20 micromachining. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriakose, S.; Parenti, P.; Cataldo, S.; Annoni, M. Green-State Micromilling of Additive Manufactured AISI316 L. J. Micro-Nano-Manuf. 2019, 7, 010904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Jia, Z.; Wang, H.; Si, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W. Tool wear appearance and failure mechanism of coated carbide tools in micro-milling of Inconel 718 super alloy. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 2016, 68, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad, S.S.; Ghani, J.A.; Haron, C.H.C.; Yazid, H. Wear Mechanism of Multilayer Coated Carbide Cutting Tool in the Milling Process of AISI 4340 under Cryogenic Environment. Materials 2022, 15, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, M.; Hafiz, M.; Ghani, J.; Izamshah, R.; Rahman, M.; Mohamad, W.; Mohamed, S. The effect of pulsating lubrication method on rake face cutting tool during end milling of inconel 718. Results Eng. 2023, 17, 100764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altas, E.; Gokkaya, H.; Karatas, M.A.; Ozkan, D. Analysis of surface roughness and flank wear using the taguchi method in milling of niti shape memory alloy with uncoated tools. Coatings 2020, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, X.; Zeng, K.; Shen, J.; Jiang, F.; Liu, Z.; Luo, W. Investigation on the exit burr formation in micro milling. Micromachines 2021, 12, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.N.; Bolar, G. Influence of End Mill Geometry on Milling Force and Surface Integrity While Machining Low Rigidity Parts. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. C 2021, 102, 1503–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Huang, X.; Li, S.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, X. Real-time reliability analysis of micro-milling processes considering the effects of tool wear. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2023, 200, 110582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeni, A.; Cappellini, C.; Ginestra, P.S.; Attanasio, A. Analytical modeling of micro-milling operations on biocompatible Ti6Al4V titanium alloy. Procedia CIRP 2022, 110, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munaro, R.; Attanasio, A.; Del Prete, A. Tool Wear Monitoring with Artificial Intelligence Methods: A Review. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yao, X.; Zhang, J.; Jin, H. Tool condition monitoring and remaining useful life prognostic based on awireless sensor in dry milling operations. Sensors 2016, 16, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindvall, R.; Bermejo, J.M.B.; Herrero, B.C.; Sirén, S.; Åberg, L.M.; Norgren, S.; M’Saoubi, R.; Bushlya, V.; Ståhl, J.-E. Degradation of multi-layer CVD-coated cemented carbide in finish milling compacted graphite iron. Wear 2023, 522, 204724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatakar, K.; Shah, V.; Binali, R.; Salur, E.; Sağlam, H.; Mikolajczyk, T.; Patange, A.D. Monitoring Built-Up Edge, Chipping, Thermal Cracking, and Plastic Deformation of Milling Cutter Inserts through Spindle Vibration Signals. Machines 2023, 11, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, P.; Santos, J.; Rocha, E. Challenges in predictive maintenance—A review. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 40, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achouch, M.; Dimitrova, M.; Ziane, K.; Karganroudi, S.S.; Dhouib, R.; Ibrahim, H.; Adda, M. On Predictive Maintenance in Industry 4.0: Overview, Models, and Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pech, M.; Vrchota, J.; Bednář, J. Predictive maintenance and intelligent sensors in smart factory: Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, F.; Glawar, R.; Nemeth, T. PriMa: A prescriptive maintenance model for cyber-physical production systems. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2019, 32, 482–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyad, S.; Kumar, S.; Bongale, A.; Bongale, A.; Patil, S.; Bongale, A.M. Estimating Remaining Useful Life in Machines Using Artificial Intelligence: A Scoping Review; Libraries, University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gharib, H.; Kovács, G. Implementation and Possibilities of Fuzzy Logic for Optimal Operation and Maintenance of Marine Diesel Engines. Machines 2024, 12, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.L.; Nascimento, D.C.; Cocolo, C.; Nicola, M.J.; Alonso, C.; Ribeiro, L.G.; Ennes, A.; Louzada, F. Reliability-Centered Maintenance: Analyzing Failure in Harvest Sugarcane Machine Using Some Generalizations of the Weibull Distribution. Model. Simul. Eng. 2018, 2018, 1241856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Pei, H.; Pang, Z.; Si, X.; Zheng, J. A Sequential Bayesian Updated Wiener Process Model for Remaining Useful Life Prediction. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 5471–5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camci, F.; Chinnam, R.B. Health-state estimation and prognostics in machining processes. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2010, 7, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, M.; Zuo, H.; Xie, J. Remaining useful life prognostics for aeroengine based on superstatistics and information fusion. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2014, 27, 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouin, M.; Gouriveau, R.; Hissel, D.; Péra, M.-C.; Zerhouni, N. Prognostics PEM fuel cell in a particle filtering framework. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyad, S.; Kumar, S.; Bongale, A.; Kamat, P.; Patil, S.; Kotecha, K. Data-Driven Remaining Useful Life Estimation for Milling Process: Sensors, Algorithms, Datasets, and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 110255–110286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.; Stammers, J.; Dominguez-Caballero, J. The application of machine learning to sensor signals for machine tool and process health assessment. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. B J. Eng. Manuf. 2021, 235, 1543–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-C.; Chang, Y.-J.; Liu, S.-L.; Chen, S.-P. Data-driven prognostics of remaining useful life for milling machine cutting tools. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Prognostics and Health Management (ICPHM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 17–20 June 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanraj, T.; Shankar, S.; Rajasekar, R.; Sakthivel, N.R.; Pramanik, A. Tool condition monitoring techniques in milling process—A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 1032–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenov, D.Y.; Gupta, M.K.; da Silva, L.R.R.; Kiran, M.; Khanna, N.; Krolczyk, G.M. Application of measurement systems in tool condition monitoring of Milling: A review of measurement science approach. Measurement 2022, 199, 111503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauptfleischová, B.; Novotný, L.; Falta, J.; Machálka, M.; Sulitka, M. In-Process Chatter Detection in Milling: Comparison of the Robustness of Selected Entropy Methods. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 6, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, J.L.F.; de Barrena, T.F.; García, A.; de Buruaga, M.S.; Badiola, X.; Vicente, J. A novel machine learning-based methodology for tool wear prediction using acoustic emission signals. Sensors 2021, 21, 5984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hase, A.; Wada, M.; Koga, T.; Mishina, H. The relationship between acoustic emission signals and cutting phenomena in turning process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 70, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzugaray-Franz, R.; Diez-Cifuentes, E.; Leal-Muñoz, E.; José, M.V.-S.; Vizán-Idoipe, A. Determination of Tool Wear in Peripheral Milling Operations Based on Acoustic Emission Signals. In Proceedings of the XV Ibero-American Congress of Mechanical Engineering, Madrid, Spain, 22–24 November 2022; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara, M.A.; Abrão, A.M.; Rubio, J.C.C.; Godoy, G.C.D.; Cordeiro, B.S. Determination of the critical undeformed chip thickness in micromilling by means of the acoustic emission signal. Precis. Eng. 2016, 46, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, K.S.B.; Venter, G.S.; Rodrigues, A.R. Experimental correlation between acoustic emission and stability in micromilling of different grain-sized materials. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 109, 2173–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Liu, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Tool wear condition monitoring by combining variational mode decomposition and ensemble learning. Sensors 2020, 20, 6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sun, W. Tool Wear Condition Monitoring in Milling Process Based on Current Sensors. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 95491–95502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, T.; Lee, C.; Zhao, R.; Jeon, S. A Simple Optical System for Miniature Spindle Runout Monitoring. Measurement 2017, 102, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, H.B.; Lima, V.T. Evaluation of Cutting Forces and Prediction of Chatter Vibrations in Milling. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2004, 26, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totis, G.; Bortoluzzi, D.; Sortino, M. Development of a universal, machine tool independent dynamometer for accurate cutting force estimation in milling. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2024, 198, 104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, F.B.; Rodrigues, A.R.; Coelho, R.T.; De Souza, A.F. Size effect and minimum chip thickness in micromilling. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2015, 89, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Duan, X.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, Y. Investigation of the tool flank wear influence on cutter-workpiece engagement and cutting force in micro milling processes. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2024, 209, 111104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Gonçalves, G. Remaining Useful Life prediction and challenges: A literature review on the use of Machine Learning Methods. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 63, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Refaie, A.; Al-atrash, M.; Lepkova, N. Prediction of the remaining useful life of a milling machine using machine learning. MethodsX 2025, 14, 103195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. Tool condition prognostics using logistic regression with penalization and manifold regularization. Appl. Soft Comput. J. 2018, 64, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.U.; Kumar, R.; Khan, A.; Singh, J.; Anwar, S.; Verma, A.; Haber, R. Sustainable machining of Inconel 718 using minimum quantity lubrication: Artificial intelligence-based process modelling. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brillinger, M.; Wuwer, M.; Hadi, M.A.; Haas, F. Energy prediction for CNC machining with machine learning. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2021, 35, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, N.; Duan, C.; Lu, L.; Chen, D. Relevance vector machine for tool wear prediction. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2019, 127, 573–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Jennings, C.; Terpenny, J.; Gao, R.X.; Kumara, S. A Comparative Study on Machine Learning Algorithms for Smart Manufacturing: Tool Wear Prediction Using Random Forests. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. Trans. ASME 2017, 139, 071018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checa, D.; Urbikain, G.; Beranoagirre, A.; Bustillo, A.; de Lacalle, L.N.L. Using Machine-Learning techniques and Virtual Reality to design cutting tools for energy optimization in milling operations. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2022, 35, 951–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Li, X.; Yin, Y.; Hong, J. Milling chatter detection by multi-feature fusion and Adaboost-SVM. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2021, 156, 107671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-H.; Le, T.-T.; Nguyen, A.-T.; Hoang, X.-T.; Nguyen, N.-T.; Nguyen, N.-K. Optimization of milling conditions for AISI 4140 steel using an integrated machine learning-multi objective optimization-multi criteria decision making framework. Measurement 2025, 242, 115837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z. Force sensor based tool condition monitoring using a heterogeneous ensemble learning model. Sensors 2014, 14, 21588–21602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiang, Z.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, W. Tool Wear State Identification Based on SVM Optimized by the Improved Northern Goshawk Optimization. Sensors 2023, 23, 8591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val, S.; Lambán, M.P.; Lucia, J.; Royo, J. Analysis and Prediction of Wear in Interchangeable Milling Insert Tools Using Artificial Intelligence Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.C.; Brito, L.C.; da Silva, M.B.; Duarte, M.A.V. Tool wear monitoring in micromilling using Support Vector Machine with vibration and sound sensors. Precis. Eng. 2021, 67, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, T. Time varying and condition adaptive hidden Markov model for tool wear state estimation and remaining useful life prediction in micro-milling. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2019, 131, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Bai, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Xu, X.; Wang, T. Tool wear monitoring strategy during micro-milling of TC4 alloy based on a fusion model of recursive feature elimination-bayesian optimization-extreme gradient boosting. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A.; Kulkarni, V.; Joshi, S.S. Tool life stage prediction in micro-milling from force signal analysis using machine learning methods. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. Trans. ASME 2021, 143, 054501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Swart, T.G. A Comprehensive Review of Deep Learning: Architectures, Recent Advances, and Applications. Information 2024, 15, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Kamal, K.; Ratlamwala, T.A.H.; Hussain, G.; Alqahtani, M.; Alkahtani, M.; Alatefi, M.; Alzabidi, A. Tool Health Monitoring of a Milling Process Using Acoustic Emissions and a ResNet Deep Learning Model. Sensors 2023, 23, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabacak, Y.E. Deep learning-based CNC milling tool wear stage estimation with multi-signal analysis. Eksploat. I Niezawodn. 2023, 25, 168082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y. A holistic approach for improving milling machine cutting tool wear prediction. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 30329–30342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Li, H. Intelligent monitoring of milling tool wear based on milling force coefficients by prediction of instantaneous milling forces. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2024, 208, 111033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Huo, D. Tool condition monitoring in micro milling of brittle materials. Precis. Eng. 2024, 87, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Xie, Q.; Yuan, Q.; Huang, H.; Li, Y. Research on a real-time monitoring method for the wear state of a tool based on a convolutional bidirectional LSTM model. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagri, S.; Manwar, A.; Varghese, A.; Mujumdar, S.; Joshi, S.S. Tool wear and remaining useful life prediction in micro-milling along complex tool paths using neural networks. J. Manuf. Process 2021, 71, 679–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Sha, K.; Tao, Y.; Ju, B.; Chen, Y. A Hybrid Deep Learning Model as the Digital Twin of Ultra-Precision Diamond Cutting for In-Process Prediction of Cutting-Tool Wear. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliyannan, D.; Thangamuthu, M.; Pradeep, P.; Gnansekaran, S.; Rakkiyannan, J.; Pramanik, A. Tool Condition Monitoring in the Milling Process Using Deep Learning and Reinforcement Learning. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2024, 13, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenov, D.Y.; da Silva, L.R.R.; Ercetin, A.; Der, O.; Mikolajczyk, T.; Giasin, K. State-of-the-art review of applications of image processing techniques for tool condition monitoring on conventional machining processes. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 130, 57–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, N.; Umar, M.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.M. Enhanced Fault Diagnosis in Milling Machines Using CWT Image Augmentation and Ant Colony Optimized AlexNet. Sensors 2024, 24, 7466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, J. On-line tool wear measurement for ball-end milling cutter based on machine vision. Comput. Ind. 2013, 64, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Robles, L.; Azzopardi, G.; Alegre, E.; Petkov, N. Machine-vision-based identification of broken inserts in edge profile milling heads. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2017, 44, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szydłowski, M.; Powałka, B.; Matuszak, M.; Kochmański, P. Machine vision micro-milling tool wear inspection by image reconstruction and light reflectance. Precis. Eng. 2016, 44, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, J.; Jha, S. Fuzzy c-means clustering based colour image segmentation for tool wear monitoring in micro-milling. Precis. Eng. 2021, 72, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H. Machine Learning: Algorithms, Real-World Applications and Research Directions. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Taisch, M. Integrated optimisation of multi-pass cutting parameters and tool path with hierarchical reinforcement learning towards green manufacturing. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 91, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xuan, J.; Shi, T. Alternative multi-label imitation learning framework monitoring tool wear and bearing fault under different working conditions. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 54, 101749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Zhang, J.; Gao, R.X.; Wang, P.; Ragai, I. Anomaly detection in milling tools using acoustic signals and generative adversarial networks. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 48, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Vakharia, V.; Chaudhari, R.; Vora, J.; Pimenov, D.Y.; Giasin, K. Tool wear prediction in face milling of stainless steel using singular generative adversarial network and LSTM deep learning models. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 121, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Huang, H.; Guo, R.; Yang, P. Tool Wear Prediction Based on Attention Long Short-term Memory Network with Small Samples. Sens. Mater. 2023, 35, 2321–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Qiu, C.; Lin, Y.; Chen, M.; Jia, X.; Li, B. A weighted adaptive transfer learning for tool tip dynamics prediction of different machine tools. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zou, B.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Ding, H.; Xue, K. Milling force prediction model based on transfer learning and neural network. J. Intell. Manuf. 2021, 32, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sun, W.; Ye, C.; Peng, B.; Fang, X.; Lin, C.; Wang, G.; Kumar, A.; Sun, W. Time-frequency Representation-enhanced Transfer Learning for Tool Condition Monitoring during milling of Inconel 718. Eksploat. I Niezawodn. 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacharalampopoulos, A.; Alexopoulos, K.; Catti, P.; Stavropoulos, P.; Chryssolouris, G. Learning More with Less Data in Manufacturing: The Case of Turning Tool Wear Assessment through Active and Transfer Learning. Processes 2024, 12, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Ahmad, R.; Li, D.; Ma, Y.; Hui, J. Industrial applications of digital twins: A systematic investigation based on bibliometric analysis. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lang, Z.Q.; Gui, Y.; Zhu, Y.P.; Laalej, H. Digital twin-based anomaly detection for real-time tool condition monitoring in machining. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 75, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Hu, T.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wei, Y. A hybrid predictive maintenance approach for CNC machine tool driven by Digital Twin. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2020, 65, 101974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, S.; Thangamuthu, M.; Gnanasekaran, S.; Rakkiyannan, J. Digital Twin-Driven Tool Condition Monitoring for the Milling Process. Sensors 2023, 23, 5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiand, C.; Kiswanto, G.; Baskoro, A.S.; Hasymi, Z.; Ko, T.J. Tool Wear Monitoring in Micro-Milling Based on Digital Twin Technology with an Extended Kalman Filter. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, D.; Wen, W.; Soon, H.G.; Kumar, A.S. Micro-milling digital twin for real-time tool condition monitoring. Manuf. Lett. 2024, 41, 1231–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Abuhmed, T.; El-Sappagh, S.; Muhammad, K.; Alonso-Moral, J.M.; Confalonieri, R.; Guidotti, R.; Del Ser, J.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Herrera, F. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): What we know and what is left to attain Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence. Inf. Fusion 2023, 99, 101805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, P.; Zamani, M.; Mostafaei, A. Machine learning prediction of mechanical properties in metal additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 91, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Jatti, V.S.; Sefene, E.M.; Paliwal, S. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) and Supervised Machine Learning-based Algorithms for Prediction of Surface Roughness of Additively Manufactured Polylactic Acid (PLA) Specimens. Appl. Mech. 2023, 4, 668–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.J.; Sohaib, M.; Kim, J.M. An explainable ai-based fault diagnosis model for bearings. Sensors 2021, 21, 4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabono, A.G.; Yahya, B.N.; Lee, S.L. Hybrid domain adaptation for sensor-based human activity recognition in a heterogeneous setup with feature commonalities. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2021, 24, 1501–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentner, N.; Susto, G.A. Heterogeneous domain adaptation and equipment matching: DANN-based Alignment with Cyclic Supervision (DBACS). Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 187, 109821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.; Kang, S. Domain-adaptive active learning for cost-effective virtual metrology modeling. Comput. Ind. 2022, 135, 103572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Zhou, R.; Ahmed, F. Multi-Modal Machine Learning in Engineering Design: A Review and Future Directions. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2024, 24, 010801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotubadi, S.V.; Pallissery, S.S.; Nguyen, V. Multi-Modal Explainable Artificial Intelligence for neural network-based tool wear detection in machining. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 144, 110141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, M.; Garland, A.; Cillessen, D.; Adamczyk, J.; Bolintineanu, D.; Heiden, M.; Fowler, E.; Boyce, B.L. Unsupervised multimodal fusion of in-process sensor data for advanced manufacturing process monitoring. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 78, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjourian, N.; Nguyen, V. Multimodal Object Detection using Depth and Image Data for Manufacturing Parts. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.09062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RQ No. | Research Questions | Discussion |

|---|---|---|

| RQ 1 | What is the difference between Milling and Micromilling processes? | Discussion: Milling and the Micromilling Process are studied. |

| RQ 2 | What types of input data (e.g., cutting forces, vibration signals, temperature, images) are used to predict tool life? | Understand the role of sensor data and image data in the prediction of tool life. |

| RQ 3 | Which machine learning, deep learning models, and computer vision techniques have been used for tool life prediction in milling and micromilling processes? | Identify types of ML, DL models, and computer vision techniques. |

| RQ 4 | How effective are different algorithms in predicting tool life, and what performance metrics are commonly used? | Compare accuracy, robustness, and limitations across algorithms. |

| RQ 5 | What are the current developments and future directions in the application of artificial intelligence for tool life prediction in machining industries? | Provide insights into ongoing research gaps, potential improvements, or new opportunities. |

| Factors | Explanation | Keywords Used |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Area of Application | “Machining” OR “Milling” OR “Milling Process” OR “Milling Operation” OR “Milling Machine” OR “Micro-Machining” OR “Micromilling” OR “Micro milling Process” OR “Micro Milling Operation” OR “Micro Milling Machine” |

| Intervention | Types of Sensors and AI Models used in the methodology | “Sensors” OR “Decision-making model” OR “Algorithms” OR “Artificial Intelligence” OR “Machine Learning” OR “Data-driven Model” OR “deep learning” OR “neural networks” OR “support vector machine” OR “random forest” OR “XGBoost” OR “Multimodal Analysis” OR “Explainable AI” OR “Fault Diagnosis” OR “Digital Twin” OR “Machine Vision” OR “Computer Vision” |

| Outcome | Represent the Specific outcome | “Remaining Useful Life” OR “Predictive Maintenance” OR “Prediction” OR “Burr Formation” OR “Tool Wear” OR “Tool Wear Monitoring” OR “Optimization” OR “tool life prediction” OR “tool wear estimation” OR “RUL estimation” OR “tool degradation” OR “cutting tool monitoring” |

| Context | Environment and Condition | “Machining Operations” OR “Machining Methods” |

| Database (Scopus, Web of Science and IEEE) | Search | Query Number of Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Master Keywords | “Machining” OR “Micromachining” OR “Milling” OR “Micromilling” OR “Micro-Milling” | 2518: Scopus 1163: Web of Science 1028: IEEE |

| Primary Keywords | “Cutting Tools” OR “Predictive Maintenance” OR “PdM” OR “Tool Condition Monitoring” OR “Remaining Useful Life” OR “RUL” OR “Tool Wear” OR “Cutting Force” OR “Tool Wear Monitoring” | |

| Secondary Keywords | “Machine Learning” OR “ML” OR “Deep Learning” OR “Data Driven model” OR “Sensors” OR “Industry 4.0” OR “Fault Detection” OR “Multi-model Analysis” OR “Explainable AI” OR “Fault Diagnosis” OR “Machine Vision” OR “Computer Vision” |

| Aspect | Conventional Milling (Macro-Milling) | Micromilling |

|---|---|---|

| Tool Size | Large Tools; Size 6 mm to 50 mm [1] | Micro Tools; Size 5 µm to 3 mm [13] |

| Tool Wear Behavior | Gradual flank and crater wear [14] | Rapid edge rounding, micro chipping [7,13] |

| Chip thickness vs. edge radius | Chip thickness > Edge Radius [15] | Chip thickness = Edge Radius [7] |

| Burr formation | Normal burr formation based on chip formation [16] | Large burr due to plowing [17] |

| Surface Roughness (Ra) | Typically, between 0.4 µm and 2 mm | Between 50 nm and 200 nm [8,11] |

| Dimensional Tolerance | ±10 µm to 50 µm [18] | ±1 µm to 5 µm [10,19] |

| Applications | Automotive, aerospace, structural machining [1] | MEMS, micro-molds, optics, biomedical micro components [10,20] |

| Sr.No. | Title | Machine Type | Year | Model and Methods Used | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Size effect and minimum chip thickness in micromilling” | Micromilling | 2015 | Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | The minimum uncut chip thickness (h_min) was found between 22% and 36% | [52] |

| 2 | “A Comparative Study on Machine Learning Algorithms for Smart Manufacturing: Tool Wear Prediction Using Random Forests” | Milling | 2017 | Random Forests, feed-forward back propagation (FFBP), ANN, and Support Vector Regression (SVR) | RFs outperform both FFBP, ANNs, and SVR in accuracy | [60] |

| 3 | “Prediction of the CNC tool wear using the machine learning technique” | Milling | 2019 | Support Vector Machine XGBoost Random Forest | Accuracy rate SVM: 62.90% XGBoost: 99.30% RF: 99.30% | [4] |

| 4 | “Time varying and condition adaptive hidden Markov model for tool wear state estimation and remaining useful life prediction in micromilling” | Micromilling | 2019 | Improved Hidden Markov Model | Accuracy rate of RUL prediction in Test (1 to 5) 87.2%, 90.7%, 89.4%, 86.7%, 91.0 | [68] |

| 5 | “Relevance vector machine for tool wear prediction” | Milling Turning | 2019 | Relevance Vector Machine (RVM) andIntegrated radial basis function-based kernel principal component analysis (KPCA_IRBF) | KPCA_IRBF reduced RMSE by over 30%. Compressed the average width of the confidence interval by more than 90%. | [59] |

| 6 | “Tool wear monitoring in micromilling using Support Vector Machine with vibration and sound sensors” | Micromilling | 2021 | Support Vector Machine model trained using four different kernels: Linear, Radial Basis Function (RBF), Polynomial, Sigmoid | Classification accuracy up to 97.54%. | [67] |

| 7 | “Energy prediction for CNC machining with machine learning” | CNC Machine | 2021 | Decision Tree Random Forest Boosted Random Forest | RF model gives the most accurate energy demand. | [58] |

| 8 | “The application of machine learning to sensor signals for machine tool and process health assessment” | Milling | 2021 | Supervised Classification k-Nearest Neighbor, Naive Bayes Decision Tree Multiclass SVM Classification ensemble Deep learning Convolutional neural network Unsupervised Dimensionality reduction Principal component analysis Clusteringk-Means clustering, Gaussian mixture model (GMM), Hierarchical clustering | The detection and classification accuracies of simulated failure modes approached 100% under certain conditions, indicating the potential effectiveness of these methods in real-world applications. | [37] |

| 9 | “Tool life stage prediction in micromilling from force signal analysis using machine learning methods” | Micromilling | 2021 | Logistic RegressionRandom Forest SVM | RF model achieved the highest accuracy of 88.5%. Accuracy increased by 40% to 73% by adding new tool force data | [70] |

| 10 | “Real-time reliability analysis of micromilling processes considering the effects of tool wear” | Micromilling | 2023 | Multi-objective Dandelion Optimizer (MDO), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) Direct Monte Carlo simulation (D-MCS) High-dimensional model representation with stochastic configuration network (HDMR-SCN) | Reliability probability comparison: D-MCS: 98.30% HDMR-SCN: 98.16% | [19] |

| 11 | “Intelligent monitoring of milling tool wear based on milling force coefficients by prediction of instantaneous milling forces” | Milling | 2024 | Temporal Convolutional Network–Long Short-Term Memory-based neural network model. (TCN–LSTM) | TCN–LSTM-based neural network model that effectively predicts milling forces from spindle current signals. The method allows without being affected by variations in spindle speeds, feeds, and depths of cut | [75] |

| 12 | “Sustainable machining of Inconel 718 using minimum quantity lubrication: Artificial intelligence-based process modeling” | Micromilling | 2024 | K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) Gaussian Regression Decision Tree Logistic Regression | The Decision Tree model outperformed R2 values MQL Dataset: 0.915 NF-MQL Dataset: 0.931 The Gaussian Regression (GR) R2 values MQL Dataset: 0.903 NF-MQL dataset: 0.915 | [57] |

| 13 | “Investigation of the tool flank wear influence on cutter-workpiece engagement and cutting force in micro milling processes” | Micromilling | 2024 | Cutting Force Analytical Model | The inclusion of tool wear (VB) improves force prediction accuracy by up to 70% points, especially along the Z-axis, which is most sensitive. Fy Force benefits the most from including VB—RMSE is reduced by about 60% at the end of the cut. | [53] |

| 14 | “Tool Condition Monitoring in the Milling Process Using Deep Learning and Reinforcement Learning” | Milling | 2024 | Feed Forward Neural Network (FFNN)Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) SARSA (State-Action-Reward-State-Action)Q-Learning | The SARSA algorithm outperformed other models and achieved an accuracy of 98.66%. Other model accuracy Q-learning: 98.50% FFNN: 98.16% LSTM: 94.85% | [80] |

| 15 | “Prediction of the remaining useful life of a milling machine using machine learning” | Milling | 2025 | Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) Regressor Random Forest Regressor (RF Regressor) Decision Tree Regressor (DT Regressor) Support Vector Regression (SVR) Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) | MLP Regressor provided the best performance metrics Accuracy: 99% Adjusted R-squared: 0.99 MAE: 3.7 MSE: 23.13 | [55] |

| 16 | “Research on a real-time monitoring method for the wear state of a tool based on a convolutional bidirectional LSTM model” | Milling | 2019 | CLSTMCBLSTMCABLSTM | Accuracy RateCLSTM 93.64%CBLSTM 95.15%CABLSTM 96.97% | [77] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Joshi, V.; Sayyad, S.; Bongale, A.; Kumar, S.; Warke, V.; Suresh, R. Towards Intelligent Manufacturing: Machine Learning, Deep Learning, and Computer Vision for Tool Wear Estimation in Milling and Micromilling Processes. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010485

Joshi V, Sayyad S, Bongale A, Kumar S, Warke V, Suresh R. Towards Intelligent Manufacturing: Machine Learning, Deep Learning, and Computer Vision for Tool Wear Estimation in Milling and Micromilling Processes. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):485. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010485

Chicago/Turabian StyleJoshi, Vaibhav, Sameer Sayyad, Arunkumar Bongale, Satish Kumar, Vivek Warke, and R. Suresh. 2026. "Towards Intelligent Manufacturing: Machine Learning, Deep Learning, and Computer Vision for Tool Wear Estimation in Milling and Micromilling Processes" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010485

APA StyleJoshi, V., Sayyad, S., Bongale, A., Kumar, S., Warke, V., & Suresh, R. (2026). Towards Intelligent Manufacturing: Machine Learning, Deep Learning, and Computer Vision for Tool Wear Estimation in Milling and Micromilling Processes. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010485