Seismic Failure Mechanism Shift in RC Buildings Revealed by NDT-Supported, Field-Calibrated BIM-Based Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

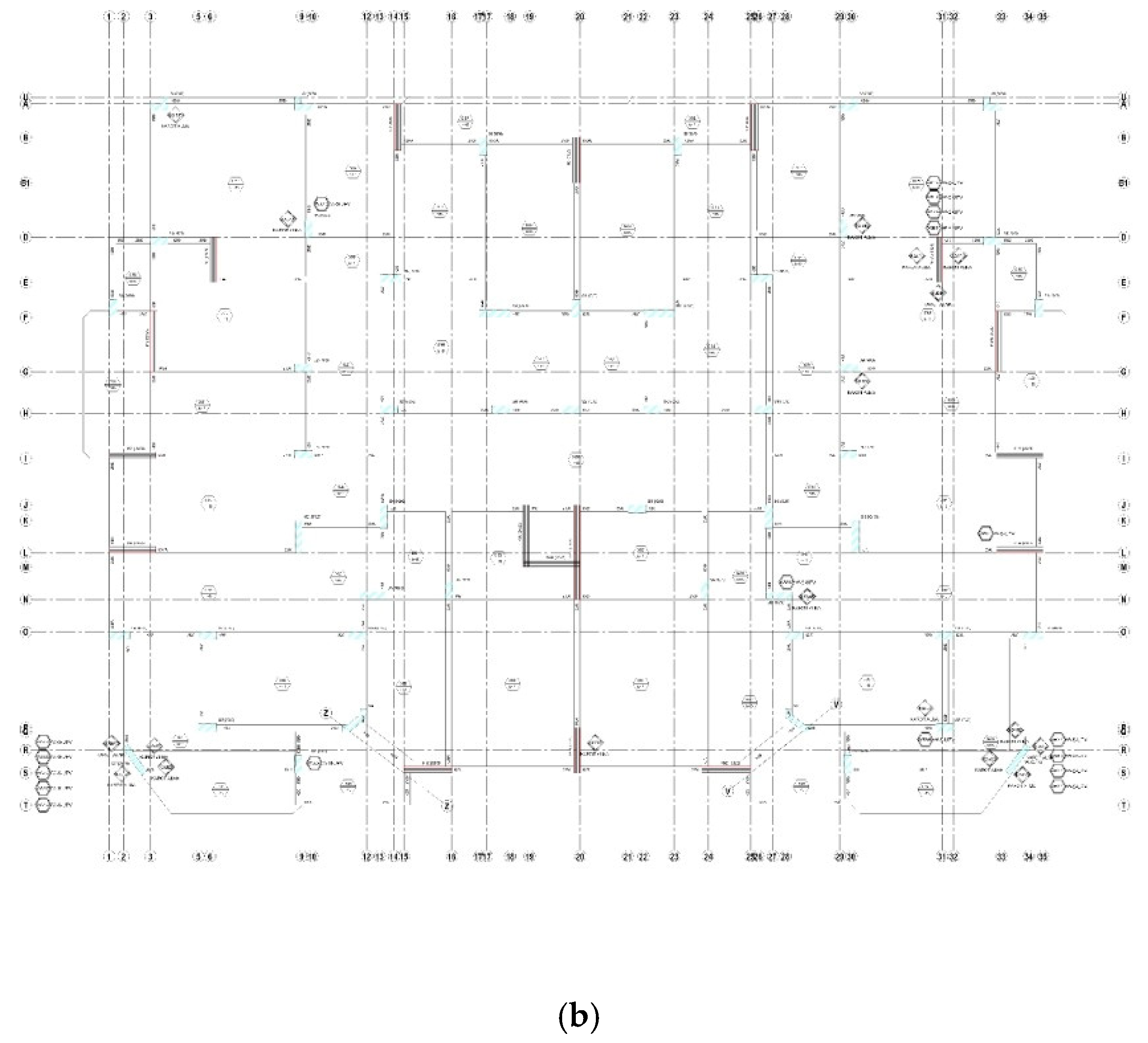

2.1. Case Study Building and Field Investigations

2.2. Testing Methodologies and Calibration Framework

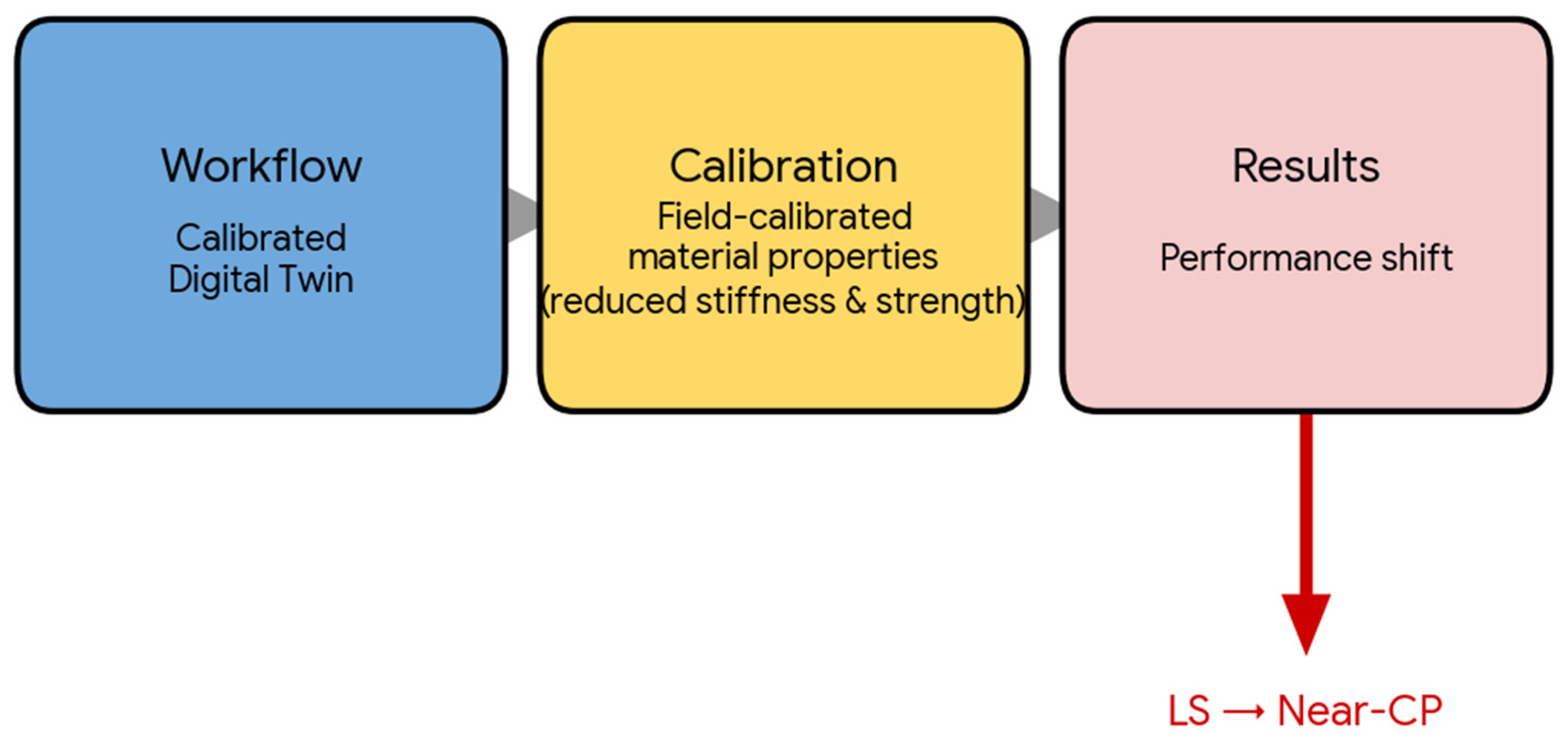

2.3. Data Integration Workflow

- Data Collection and Pre-Processing. Field measurements, including both destructive and NDT data, were digitized, cleaned, and organized together with descriptive metadata to ensure traceability. Recorded attributes included structural element type, test location, measurement conditions, and associated uncertainties.

- Model Development in BIM. A detailed building information model was developed using a BIM-based structural modeling platform (ProtaStructure), in which geometry, member dimensions, and reinforcement layouts were represented as parametric entities. The BIM model served as the digital backbone for subsequent integration of calibrated material properties and analytical modeling.

- Data Embedding and Calibration. NDT-derived strength estimates were calibrated against core test results using the regression coefficients defined in Section 2.2. The calibrated material parameters were then embedded into the BIM model as custom property sets (Psets) assigned at the element level. This approach ensured that material properties reflected field-measured characteristics rather than nominal design assumptions, while preserving spatial variability among structural components.

- Digital Twin Synchronization. The BIM model was subsequently extended into a Level-2 static digital twin, enabling periodic semantic updates based on post-earthquake field observations and calibrated test results. Although real-time bi-directional data exchange was not implemented, the adopted configuration provides a traceable and sufficiently responsive framework for post-earthquake engineering assessments that require rapid yet controlled model updates.

2.4. Digital Twin Modeling and Seismic Performance Analysis

- Plastic hinge rotations for primary and secondary members;

- Interstory drift limits of approximately 0.7%, 2.5%, and 4.0% for IO, LS, and CP, respectively [45];

- Shear and axial capacity ratios for critical vertical elements;

- Global stability verification for P–Δ effects and torsional irregularities [50].

2.5. Interoperability Challenges in BIM–DT Data Exchange

3. Results

3.1. Field Investigation Findings

3.2. Calibrated Digital Twin Model

3.3. Seismic Performance Analysis Results

3.4. Comparison with Uncalibrated Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Comparison with Existing Literature

4.3. Implications of the Study

4.3.1. Practical Implications

4.3.2. Theoretical Implications

4.4. Limitations of the Study

4.5. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BIM | Building Information Modeling |

| CoV | Coefficient of Variation |

| CP | Collapse Prevention |

| DBE | Design-Basis Earthquake |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| GPR | Ground-Penetrating Radar |

| IO | Immediate Occupancy |

| LS | Life Safety |

| MCE | Maximum-Considered Earthquake |

| MVDs | Model View Definitions |

| Near-CP | Near-Collapse Prevention |

| NDT | Non-Destructive Testing |

| PBEE | Performance-Based Earthquake Engineering |

| PGA | Peak Ground Acceleration |

| Psets | Property Sets |

| Pushover | Nonlinear Static (Pushover) Analysis |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| RC | Reinforced Concrete |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodologies |

| UPV | Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity |

References

- Işık, E.; Avcil, F.; Hadzima-Nyarko, M.; İzol, R.; Büyüksaraç, A.; Arkan, E.; Radu, D.; Özcan, Z. Seismic Performance and Failure Mechanisms of Reinforced Concrete Structures Subject to the Earthquakes in Türkiye. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suquillo, B.; Rojas, F.; Massone, L.M. Seismic Performance Evaluation of a Chilean RC Building Damaged during the Mw8.8 Chile Earthquake. Buildings 2024, 14, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maidiawati, S.; Subiyanto, B. Seismic Analysis of Damaged Buildings Based on Post-Earthquake Investigation of the 2018 Palu Earthquake. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaulagain, H.; Rodrigues, H.; Spacone, E.; Varum, H. Seismic Response of Current RC Buildings in Kathmandu Valley. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2015, 53, 791–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, G.A.; Dong, Y.; Zhai, C. Performance-based probabilistic framework for seismic risk, resilience, and sustainability assessment of reinforced concrete structures. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2020, 23, 1454–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEMA. Seismic Performance Assessment of Buildings (FEMA P-58); Federal Emergency Management Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- EN 1998-1; Eurocode 8: Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance—Part 1: General Rules, Seismic Actions and Rules for Buildings. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- ASCE/SEI 41-17; Seismic Evaluation and Retrofit of Existing Buildings. American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2017.

- PEER Tall Buildings Initiative (PEER-TBI). Guidelines for Performance-Based Seismic Design of Tall Buildings; Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Amini, M.I. Earthquake Performance and Cost Comparison of Core Wall and Tunnel Formwork RC High-Rise Buildings. Master’s Thesis, Istanbul Kültür University, Istanbul, Türkiye, 2022. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11413/8709 (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Bagasi, O.; Nawari, N.O.; Alsaffar, A. BIM and AI in Early Design Stage: Advancing Architect–Client Communication. Buildings 2025, 15, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, O.O.; Nawari, N.O.; Lawal, O. AI-Enabled Cognitive Predictive Maintenance of Urban Assets Using City Information Modeling—Systematic Review. Buildings 2025, 15, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, S.; Jin, X.; Das, P.; Gunasekara, K.; Samaratunga, M. A strategic framework for digital maturity of design and construction through a systematic review and application. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2022, 31, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.O.; Sabadini, F.S.; Costa, K.A.; Hernandez Mena, C.; NikooFard, V.; Ribeiro, R.B. Maturity model for the implementation of digital twins in a Brazilian public health unit. Res. Soc. Dev. 2025, 14, e7114849393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Kim, H.Y.; Shin, M.H. Quantitative and Qualitative Benefits of Using BIM in Design and Construction Stages for Railway Development. Buildings 2025, 15, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammag, B.Q.D.; Jian, D.; Dammag, A.Q.; Alshawabkeh, Y.; Almutery, S.; Habibullah, A.; Baik, A. Modeling Ontology-Based Decay Analysis and HBIM for the Conservation of Architectural Heritage: The Big Gate and Adjacent Curtain Walls in Ibb, Yemen. Buildings 2025, 15, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Ji, H.W.; Kwak, H.; Chung, T.; Bae, M. Schema-Agnostic Data Type Inference and Validation for Exchanging JSON-Encoded Construction Engineering Information. Buildings 2025, 15, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Moeilak, L.S.M.; Abuhalimeh, D.; Mattar, Y.; Beheiry, S. Barriers to Integrating BIM and Sustainable Practices in UAE Construction Projects: An Analytic Hierarchy Process Approach. In Proceedings of the 5th European International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management (IEOM), Rome, Italy, 26–28 July 2022; pp. 390–401. Available online: https://ieomsociety.org/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Matarneh, R.; Hamed, S. Barriers to the Adoption of Building Information Modeling in the Jordanian Building Industry. Open J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 7, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porco, F.; Ruggieri, S.; Uva, G. Seismic assessment of irregular existing buildings: Appraisal of the influence of compressive strength variation by means of nonlinear conventional and multimodal static analysis. Ing. Sismica 2018, 35, 64–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Zaidi, S.K.A.; Jain, S.C.; Krishna, K.V.S.M. Reliability of Non-Destructive Testing Methods in the Assessment of the Strength of Concrete Columns Reinforced with Two Layers of Transverse Confining Stirrups: Empirical Evidence. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 8, 3450–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekhteraey, N.; Ekhteraei, M.; Sattari, M.A. Non-Destructive Concrete Strength Prediction Using AI: A Comparative Study of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models. Res. Sq. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdal, M.; Şimşek, O. Bazı tahribatsız deney metotlarının vakum uygulanmış betonların basınç dayanımlarının belirlenmesindeki performanslarının incelenmesi. Gazi Üniversitesi Mühendislik Mimar. Fakültesi Derg. 2013, 21, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tuncay, E.; Köken, E.; Kılınçarslan, Ş. Estimation of Concrete Strength Properties through the Response Surface Methodology, Genetic Algorithm, and Artificial Neural Networks. Mühendislik Bilim. Ve Tasarım Derg. 2022, 10, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawil, D.; Martín-Pérez, B.; Sanchez, L.F.M.; Noël, M. Detection of corrosion effects on prestressed concrete bridge deck slabs from the Champlain Bridge through non-destructive testing techniques. Struct. Concr. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoła, J.; Bien, J.; Sadowski, L.; Schabowicz, K. Non-Destructive and Semi-Destructive Diagnostics of Concrete Structures in Assessment of Their Durability. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 2015, 63, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-C.; Lee, S.-H.; Park, M.; Kim, K.-S. Remaining Service Life Evaluation of Reinforced Concrete Buildings Considering Failure Probability of Members. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2025, 19, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, M.E. Physics-guided self-supervised few-shot learning for ultrasonic defect detection in concrete structures. Buildings 2025, 15, 4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselton, C.B.; Goulet, C.A.; Mitrani-Reiser, J.; Beck, J.L.; Deierlein, G.G.; Porter, K.A.; Stewart, J.P.; Taciroğlu, E. An assessment to benchmark the seismic performance of a code-conforming reinforced-concrete moment-frame building. In Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center (PEER) Report 2008, Report No. PEER 2007/12; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C42/C42M; Standard Test Method for Obtaining and Testing Drilled Cores and Sawed Beams of Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM C805/C805M; Standard Test Method for Rebound Number of Hardened Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM C597; Standard Test Method for Pulse Velocity Through Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- ASTM C803/C803M; Standard Test Method for Penetration Resistance of Hardened Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- Breysse, D.; Balayssac, J.P.; Biondi, S.; Borosnyói, A.; Candigliota, E.; Chiauzzi, L.; Grantham, M.; Gunes, O.; Luprano, V.; Pfister, V.; et al. Non-destructive assessment of in-situ concrete strength: Comparison of approaches through an international benchmark. Mater. Struct. 2017, 50, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trtnik, G.; Kavčič, F.; Turk, G. Prediction of Concrete Strength Using Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity and Artificial Neural Networks. Ultrasonics 2009, 49, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, T.; Ulucan, M.; Alyamaç, K.E. Development of Combined Methods Using Non-Destructive Test Methods to Determine the In-Place Strength of High-Strength Concretes. Processes 2023, 11, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 12504-1; Testing Concrete—Part 1: Cored Specimens—Taking, Examining and Testing in Compression. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Miano, A.; Ebrahimian, H.; Jalayer, F.; Prota, A. Reliability Estimation of the Compressive Concrete Strength Based on Non-Destructive Tests. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolborea, B.; Baera, C.; Dan, S.; Gruin, A.; Burduhos-Nergis, D.-D.; Vasile, V. Concrete Compressive Strength by Means of Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity and Moduli of Elasticity. Materials 2021, 14, 7018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofaro, M.T.; Viti, S.; Tanganelli, M. New predictive models to evaluate concrete compressive strength using the SonReb method. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 26, 100962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, M.E.; Fenerli, C. Investigation of the Integrated Use of NDT Methods and BIM Technology in Performance Analysis Studies of Earthquake-Affected Reinforced Concrete Structures. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Non-Destructive Testing in Civil Engineering (NDT-CE 2025), Izmir, Turkey, 24–26 September 2025; Volume 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.K.; Cao, H. Combining Multiple NDT Methods to Improve Testing Effectiveness. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 1310–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chow, C.L.; Lau, D. Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Non-Destructive Defect Detection for Civil Infrastructure. Autom. Constr. 2025, 171, 105996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musella, C.; Serra, M.; Menna, C.; Asprone, D. Building Information Modeling and artificial intelligence: Advanced technologies for the digitalisation of seismic damage in existing buildings. Struct. Concr. 2021, 22, 2761–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TBDY-2018; Türkiye Bina Deprem Yönetmeliği (Turkish Seismic Code). AFAD: Ankara, Türkiye, 2018.

- Gupta, B.; Kunnath, S.K. Adaptive spectra-based pushover procedure for seismic evaluation of structures. Earthq. Spectra 2000, 16, 367–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneş, N.; Ulucan, Z.Ç. Comparison of Two Differently Designed Seismically Isolated Buildings. Fırat Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2020, 32, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Q. Computer-Vision and Machine-Learning-Based Seismic Damage Assessment of Reinforced Concrete Structures. Buildings 2023, 13, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.V.; Tatipamula, M.; Nguyen, H.X. Cloud-Based Digital Twinning for Structural Health Monitoring Using Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 3820–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivori, D.; Ierimonti, L.; Venanzi, I.; Ubertini, F.; Cattari, S. An Equivalent Frame Digital Twin for the Seismic Monitoring of Historic Structures: A Case Study on the Consoli Palace in Gubbio, Italy. Buildings 2023, 13, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, M.E. A Framework for Leveraging Semantic Interoperability between BIM Applications. In ECPPM 2021—eWork and eBusiness in Architecture, Engineering and Construction; CRC Press: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibenik, G.; Kovacic, I. Proposal for a Discipline-Specific Open Exchange Framework. In Proceedings of the 35th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction (ISARC 2018), Berlin, Germany, 20–25 July 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Eastman, C.; Solihin, W. Rules and Validation Processes for Interoperable BIM Data Exchange. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2020, 7, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Deng, X. Interoperability Analysis of IFC-Based Data Exchange between Heterogeneous BIM Software. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2018, 24, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, M.; Eastman, C.; Teizer, J. An Ontology-Based Analysis of the Industry Foundation Class Schema for Building Information Model Exchanges. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2015, 29, 940–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proverbio, E.; Venturi, V. Reliability of Nondestructive Tests for On-Site Concrete Strength Assessment. In Proceedings of the 10DBMC International Conference on Durability of Building Materials and Components, Lyon, France, 17–20 April 2005; p. TT8-227. [Google Scholar]

- Oke, D.A.; Oladiran, G.F.; Raheem, S.B. Correlation between Destructive Compressive Testing (DT) and Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) for Concrete Strength. Int. J. Eng. Res. Gen. Sci. 2017, 3, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, A.F. Statistical equations to estimate the in-situ concrete compressive strength from non-destructive tests. J. Eng. 2018, 24, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, A.M. Properties of Concrete, 5th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.A.R.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Bi, W.; Al-Dhubai, F.M.A. Seismic Vulnerability Assessment of Residential RC Buildings in Yemen Using Incremental Dynamic Analysis (IDA). Buildings 2025, 15, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandak, N.; Kumavat, H. SonReb Method for Evaluation of Compressive Strength of Concrete. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 810, 012071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Gardoni, P.; Hurlebaus, S. Predicting Concrete Compressive Strength Using Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity and Rebound Number. ACI Mater. J. 2011, 108, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maidi, M.; Lifshitz Sherzer, G.; Shufrin, I.; Gal, E. Seismic Resilience of CRC- vs. RC-Reinforced Buildings: A Long-Term Evaluation. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, G.; Ecemiş, A.S.; Korkmaz, S.Z.; Arslan, M.H.; Korkmaz, H.H. Building damages after Elazığ, Turkey earthquake on January 24, 2020. Nat. Hazards 2021, 109, 161–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 206; Concrete—Specification, Performance, Production and Conformity. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- Ubertini, F.; Cavalagli, A.; Comanducci, G. Vibration-Based Structural Health Monitoring of a Historic Bell Tower Using Output-Only Measurements and Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Struct. Health Monit. 2016, 15, 438–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, A.; Li, J. Progressive Finite Element Model Calibration of a Long-Span Suspension Bridge Based on Ambient Vibration and Static Measurements. Eng. Struct. 2010, 32, 2546–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahari, S.F.; Abazarsa, F.; Ghannad, M.; Taciroğlu, E. Response-Only Modal Identification of Structures Using Strong Motion Data. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2013, 42, 1219–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajfar, P. A Nonlinear Analysis Method for Performance-Based Seismic Design. Earthq. Spectra 2000, 16, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, K.; Krawinkler, H. Global Collapse of Frame Structures Under Seismic Excitations; Report No. 152; The John A. Blume Earthquake Engineering Center, Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffarzadeh, H.; Talebian, N.; Kohandel, R. Seismic Demand Evaluation of Medium Ductility RC Moment Frames Using Nonlinear Procedures. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2013, 12, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülkan, P.; Sözen, M.A. Inelastic Responses of Reinforced Concrete Structures to Earthquake Motions. ACI J. Proc. 1974, 71, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AFAD. 6 Şubat 2023 Kahramanmaraş Depremleri Raporu (Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes Report); Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD): Ankara, Türkiye, 2023.

- TMMOB İnşaat Mühendisleri Odası. 6 Şubat 2023 Kahramanmaraş Depremleri Teknik Raporu; TMMOB İnşaat Mühendisleri Odası: Ankara, Türkiye, 2023; Available online: https://www.imo.org.tr/Eklenti/8624,deprem-rapor-2-webpdf.pdf?0 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Benek, M.; Aktan, S. Seismic Risk Evaluation of Existing Reinforced Concrete Buildings: A Case Study for Çanakkale-Türkiye. J. Adv. Res. Nat. Appl. Sci. 2024, 10, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulay, T.; Priestley, M.J.N. Seismic Design of Reinforced Concrete and Masonry Buildings; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Borzi, B.; Pinho, R.; Crowley, H. Simplified Pushover-Based Vulnerability Analysis for Large-Scale Assessment of RC Buildings. Eng. Struct. 2008, 30, 804–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, F.; Fenves, G.L.; Scott, M.H. Open System for Earthquake Engineering Simulation (OpenSees); Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2000; Available online: https://opensees.berkeley.edu/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Işık, E.; Ulu, A.E.; Aydın, M.C. A Case Study on the Updates of Turkish Rapid Visual Screening Methods for Reinforced-Concrete Buildings. Bitlis Eren Univ. J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.H.; Dai, K.Y.; Li, Y.S. Variability in Corrosion Damage Models and Its Effect on Seismic Collapse Fragility of Aging Reinforced Concrete Frames. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 295, 123654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobarah, A. Seismic Assessment of Existing Reinforced Concrete Structures. Prog. Struct. Eng. Mater. 2000, 2, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevim, B.; Ayvaz, Y.; Akbulut, S.; Aydiner, M.F.; Uzun, S.; Ari, A. Seismic Performance and Damage Evaluation of Reinforced Concrete Structures Based on Field Investigation Made after February 6, 2023, Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes. J. Earthq. Tsunami 2024, 18, 2350032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbaş, Y.; Mercimek, Ö.; Anıl, Ö.; Çelik, A.; Akkaya, S.T. Design Deficiencies, Failure Modes and Recommendations for Strengthening in Reinforced Concrete Structures Exposed to the 6 February 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes (Mw 7.7 and Mw 7.6). Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 3153–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, K.; Ishida, T.; Kishi, T. Multi-Scale Modeling of Structural Concrete, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-415-46554-0. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti, V.; Arezzo, D.; Carbonari, S.; Gara, F. Dynamic Monitoring of Buildings as a Diagnostic Tool during Construction Phases. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 46, 103764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauria, M.; Azzalin, M. Digital Transformation in the Construction Sector: A Digital Twin for Seismic Safety in the Lifecycle of Buildings. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B.; Gil, A.; Bolina, F.; Tutikian, B. Thermal damage evaluation of full-scale concrete columns exposed to high temperatures using scanning electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction. DYNA 2018, 85, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test Method | N (Samples) | Mean (MPa) | Std. Dev. (MPa) | CoV (%) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core (Destructive) | 18 | 18.6 | 3.9 | 21.0 | Baseline (ASTM C42) |

| Schmidt Hammer (NDT) | 18 | 23.4 | 4.5 | 19.2 | ASTM C805 |

| UPV (NDT) | 18 | 22.6 | 3.7 | 16.4 | ASTM C597 |

| Windsor Probe (NDT) | 18 | 21.9 | 4.2 | 19.1 | ASTM C803 |

| SonReb (Combined) | 18 | 22.99 | 3.2 | 13.9 | Rebound + UPV |

| WinSonReb (Combined) | 18 | 21.33 | 2.8 | 13.1 | Rebound + UPV + Windsor |

| Method | Input Parameters | Typical R2 Range | Mean Absolute Error (MAE, %) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rebound Hammer (NDT) | R | 0.50–0.70 | 15–25 | [38] |

| UPV (NDT) | V | 0.60–0.75 | 12–20 | [39] |

| SonReb | R, V | 0.80–0.90 | 8–12 | [40] |

| WinSonReb | R, V, W | 0.85–0.93 | 5–10 | [41] |

| AI-based Models | R, V, W (+features) | 0.90–0.98 | <5 | [43] |

| Test Method | N (Samples) | Mean (MPa) | Std. Dev. (MPa) | CoV (%) | R2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core (Destructive) | 18 | 18.60 | 3.9 | 21.0 | – | – |

| Schmidt Hammer (NDT) | 18 | 23.40 | 4.5 | 19.2 | – | – |

| UPV (NDT) | 18 | 22.60 | 3.7 | 16.4 | – | – |

| Windsor Probe (NDT) | 18 | 21.90 | 4.2 | 19.1 | – | – |

| SonReb (Combined) | 18 | 22.99 | 3.2 | 13.9 | 0.87 | <0.05 |

| WinSonReb (Combined) | 18 | 21.33 | 2.8 | 13.1 | 0.87 | <0.05 |

| Parameter | Design Model (Nominal) | Calibrated Digital Twin (Field-Based) | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concrete Strength (fck, MPa) | 20.0 | 18.6 | –7.0 |

| Reinforcement Yield Strength (fyk, MPa) | 420 | 415 | –1.2 |

| Modulus of Elasticity (E, MPa) | 30,000 | 27,500 | –8.3 |

| Concrete Class (EN 206 [65]) | C20/25 | C16/20 | — |

| Coefficient of Variation (CoV, %) | — | >20 | — |

| Story | Direction | Drift Ratio (%) | ASCE 41-17 Limit (%) | Performance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | X | 1.8 | 2.5 | LS OK |

| 6 | Y | 3.4 | 2.5 | >LS |

| 5 | X | 2.1 | 2.5 | LS OK |

| 5 | Y | 2.8 | 2.5 | Slight Exceedance |

| 4–1 | X | ≤2.0 | 2.5 | LS OK |

| 4–1 | Y | ≤2.5 | 2.5 | LS OK |

| Parameter | Direction X | Direction Y |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Base Shear (kN) | 2050 | 1980 |

| Roof Displacement (m) | 0.19 | 0.21 |

| Performance Point Displacement (m) | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| Performance Level | LS | Near-CP |

| Fundamental Period (s) | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| Dominant Mode Type | Translational | Torsional |

| Parameter | Uncalibrated Model | Calibrated DT | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Period (s) | 0.72 | 0.85 | +18.1 |

| Max. Base Shear (kN) | 2280 | 1980 | −13.2 |

| Roof Displacement (m) | 0.13 | 0.16 | +22.0 |

| Performance Level | LS | Near-CP | — |

| Reference | Focus | Key Findings | Distinction of This Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| [56,57,58] | NDT overestimation in RC structures | Uncalibrated NDT yields 15–25% higher predicted strength | Confirms and quantifies bias through WinSonReb calibration |

| [44] | Regression calibration post-earthquake | Regression improves correlation but limited to strength refinement | Extends calibration to behavioral prediction (failure mode shift) |

| [73,74] | Field-observed RC damage patterns | Column and wall hinging near cores | Replicated via DT-based calibrated analysis |

| [86] | BIM–DT integration | Conceptual frameworks for data interoperability | Provides validated, field-calibrated empirical workflow |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Eren, M.E.; Fenerli, C. Seismic Failure Mechanism Shift in RC Buildings Revealed by NDT-Supported, Field-Calibrated BIM-Based Models. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010455

Eren ME, Fenerli C. Seismic Failure Mechanism Shift in RC Buildings Revealed by NDT-Supported, Field-Calibrated BIM-Based Models. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):455. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010455

Chicago/Turabian StyleEren, Mehmet Esen, and Cenk Fenerli. 2026. "Seismic Failure Mechanism Shift in RC Buildings Revealed by NDT-Supported, Field-Calibrated BIM-Based Models" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010455

APA StyleEren, M. E., & Fenerli, C. (2026). Seismic Failure Mechanism Shift in RC Buildings Revealed by NDT-Supported, Field-Calibrated BIM-Based Models. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010455