RDINet: A Deep Learning Model Integrating RGB-D and Ingredient Features for Food Nutrition Estimation

Abstract

1. Introduction

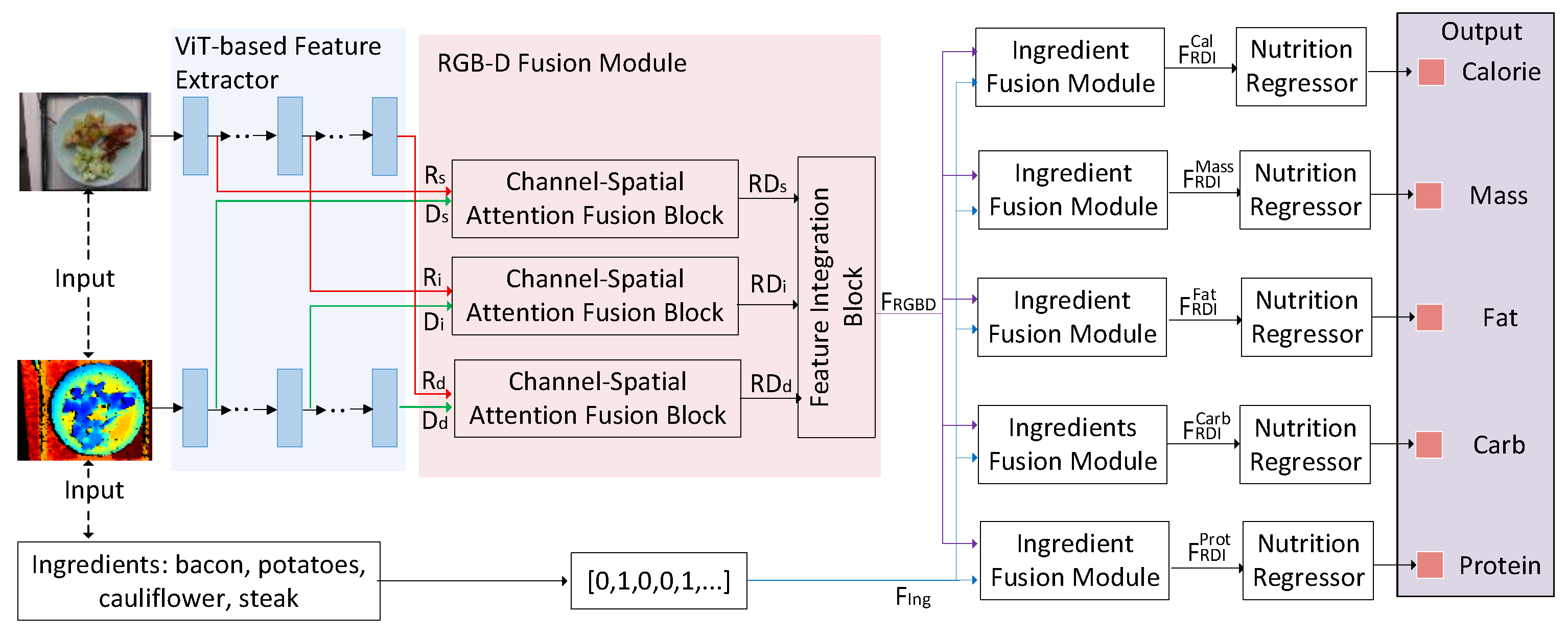

- We design an RGB-D fusion module that integrates appearance features from RGB images and geometric priors from depth images, achieving joint understanding of food appearance and geometric morphology without explicit 3D reconstruction, thereby effectively reducing nutritional estimation errors.

- We propose an ingredient fusion module centered on cross-attention, which leverages cross-attention mechanisms to dynamically modulate visual feature responses using ingredient priors. This design not only effectively alleviates the challenge of distinguishing visually similar ingredients with vastly different nutritional profiles but also compensates for the missing information caused by nutritionally critical components that are difficult to recognize visually. By doing so, the model can reliably infer latent nutritional attributes from explicit visual observations, significantly reducing nutrient estimation errors. This constitutes the core methodological innovation of our work.

- We evaluated RDINet on the public dataset Nutrition5k, and the results demonstrate its excellent performance across multiple nutrient estimation tasks, outperforming existing methods.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Methods

2.2. Image-Based Methods

2.3. Volume Modeling Approaches

2.4. Ingredient Fusion Methods

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methods

| Algorithm 1: Algorithm of RDINet |

| input: images |

| images |

| ingredients |

| ground truth values |

| training epochs |

| batch size |

| model |

| output: |

| Initialize all weights |

| for do |

| Divide {} to minibatches with size |

| for ∈ minibatches do |

| for do |

| for do |

| for do |

| backward () |

| update all weights |

| end |

| end |

| return |

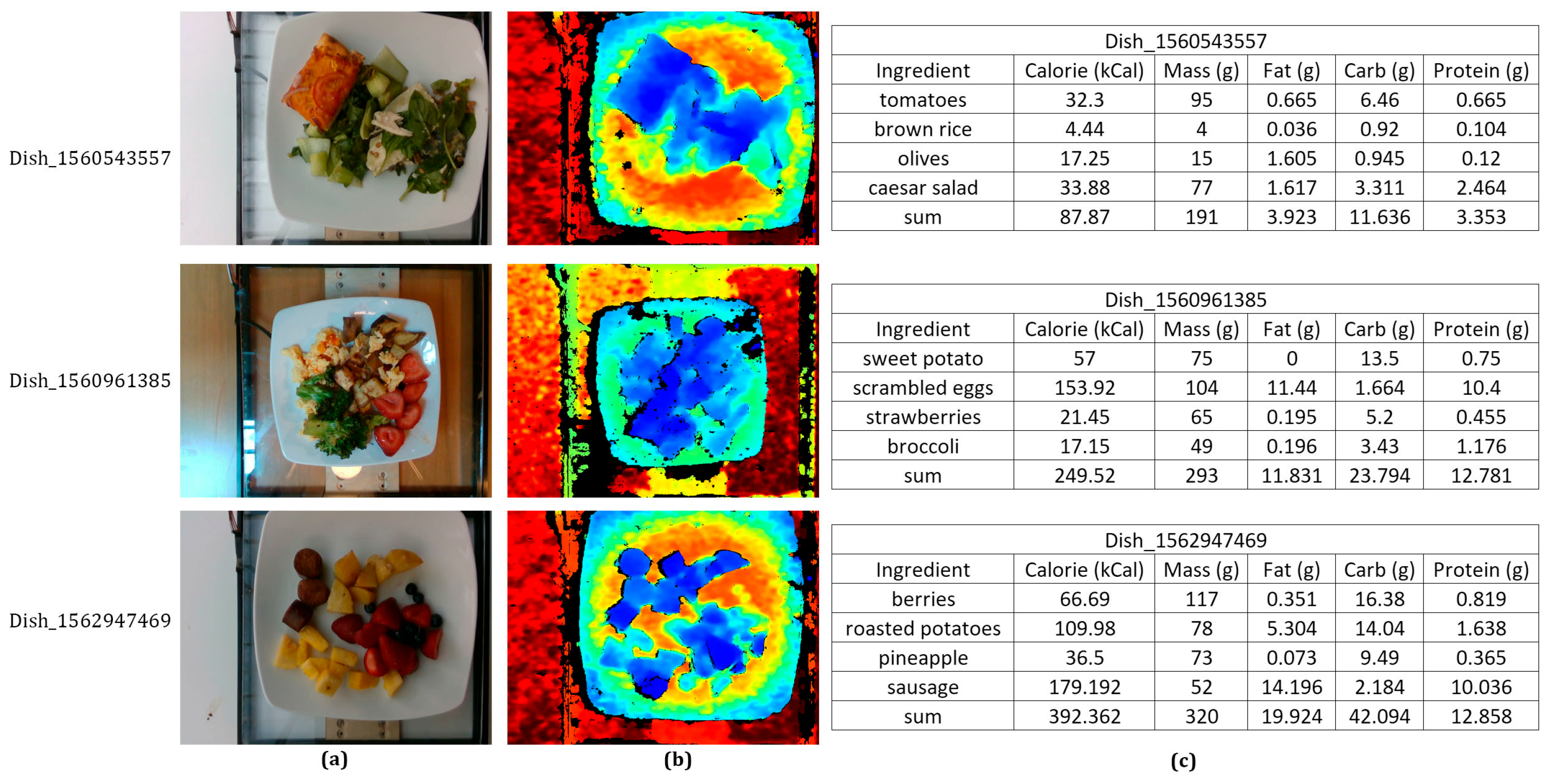

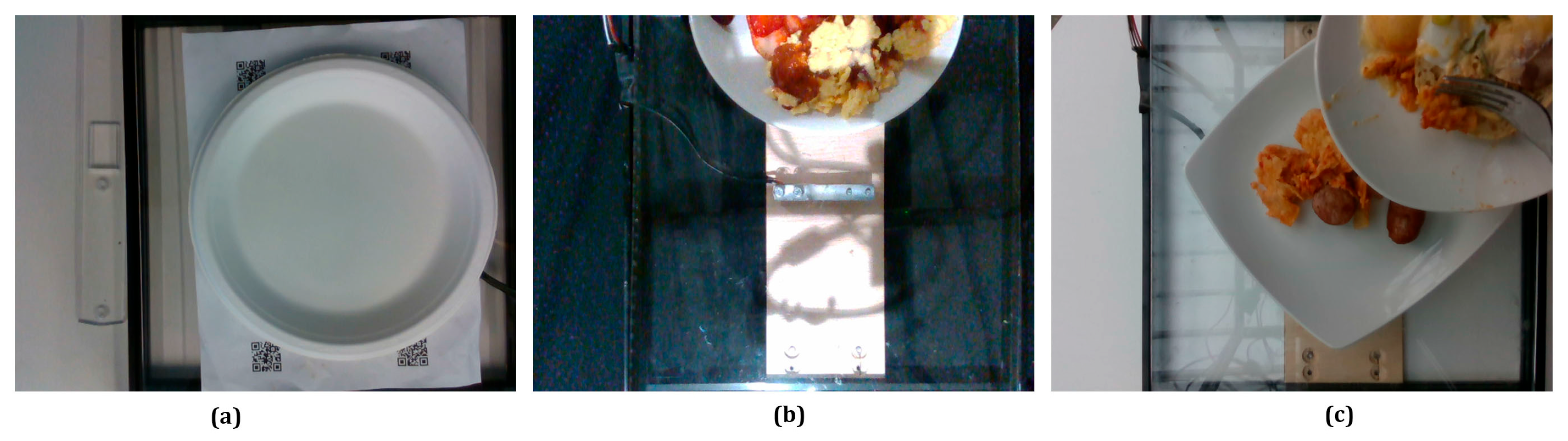

3.2. Dataset

3.3. ViT-Based Feature Extractor

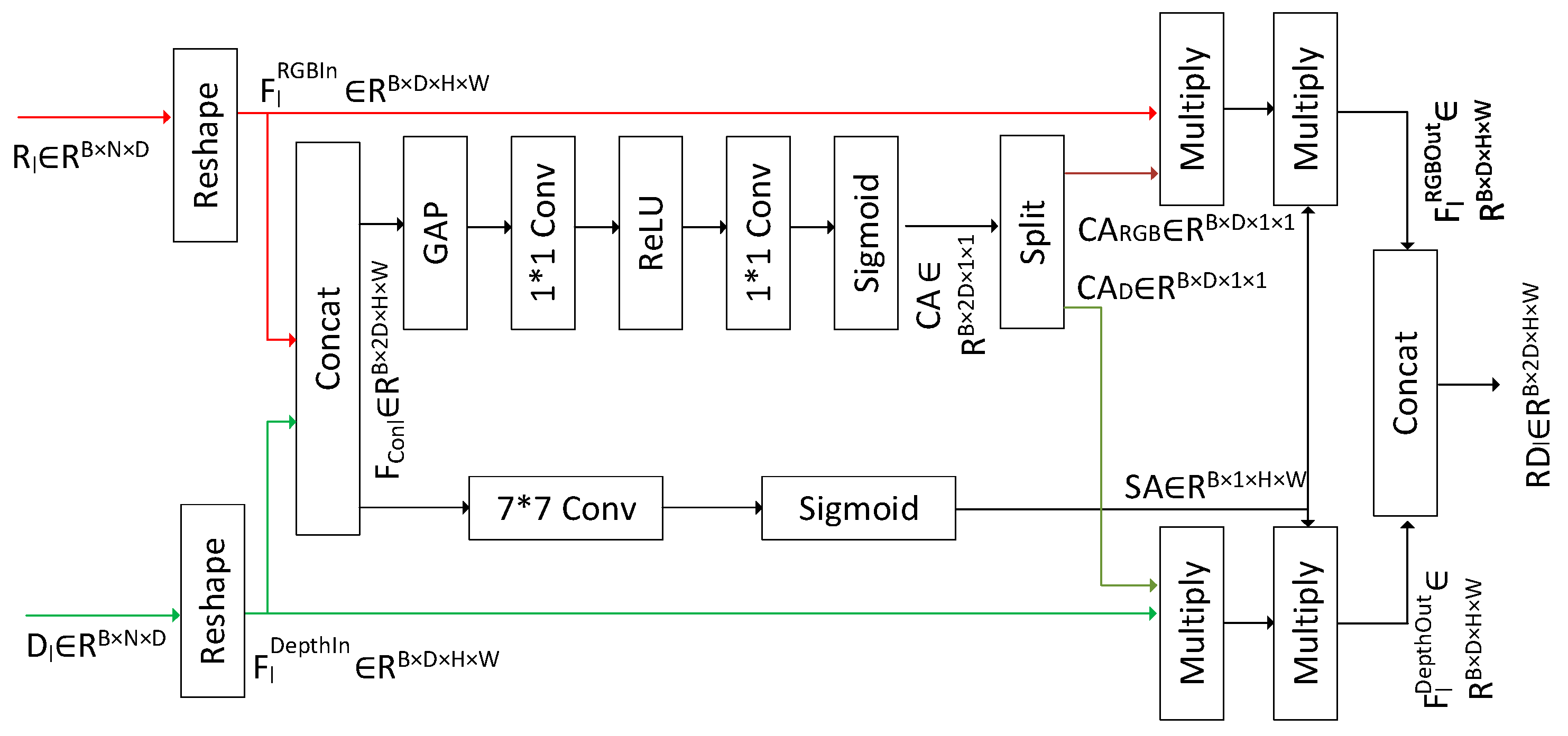

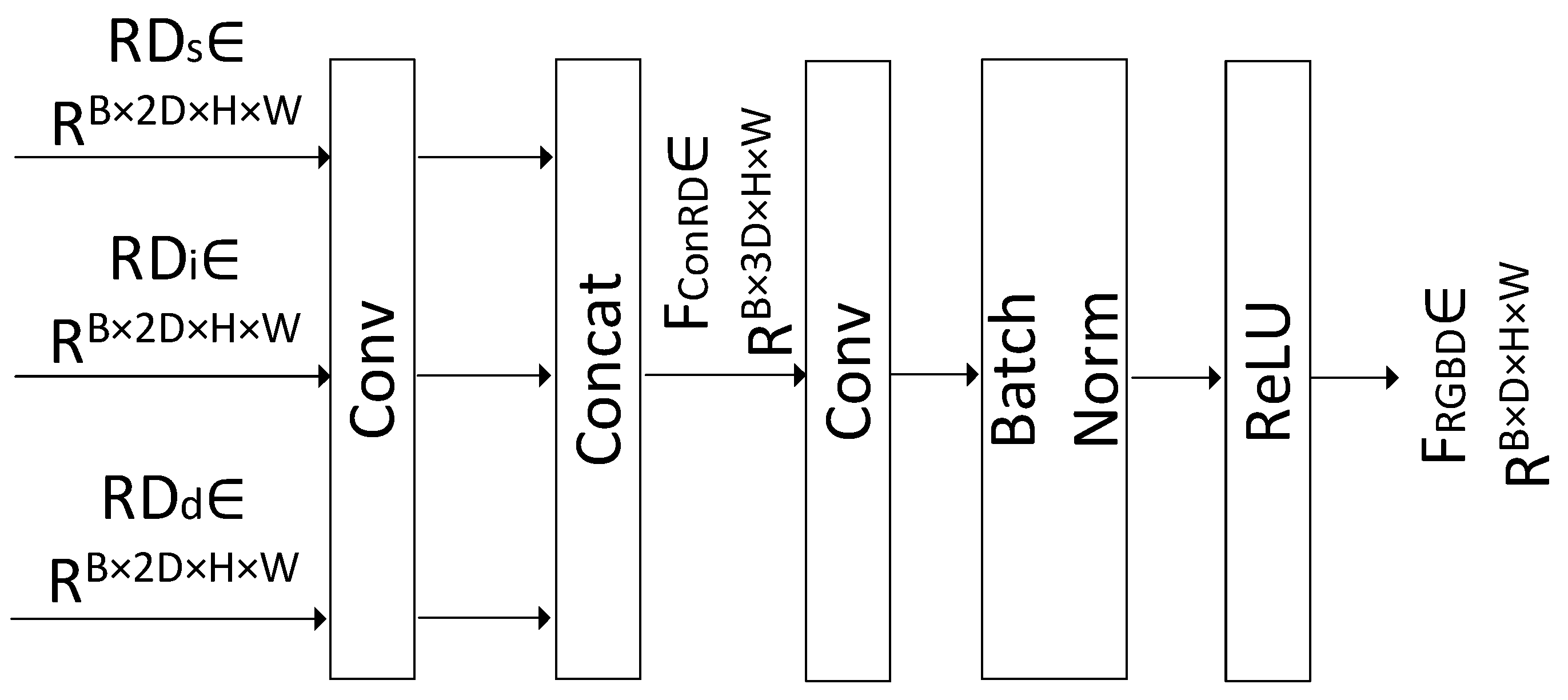

3.4. RGB-D Fusion Module

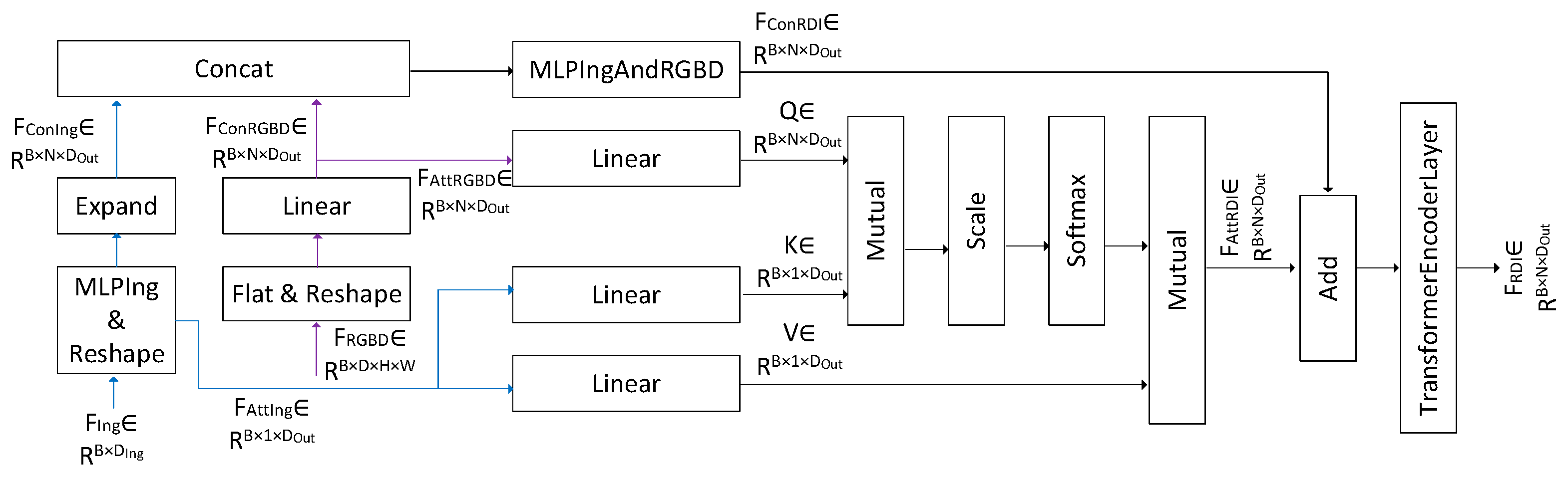

3.5. Ingredient Fusion Module

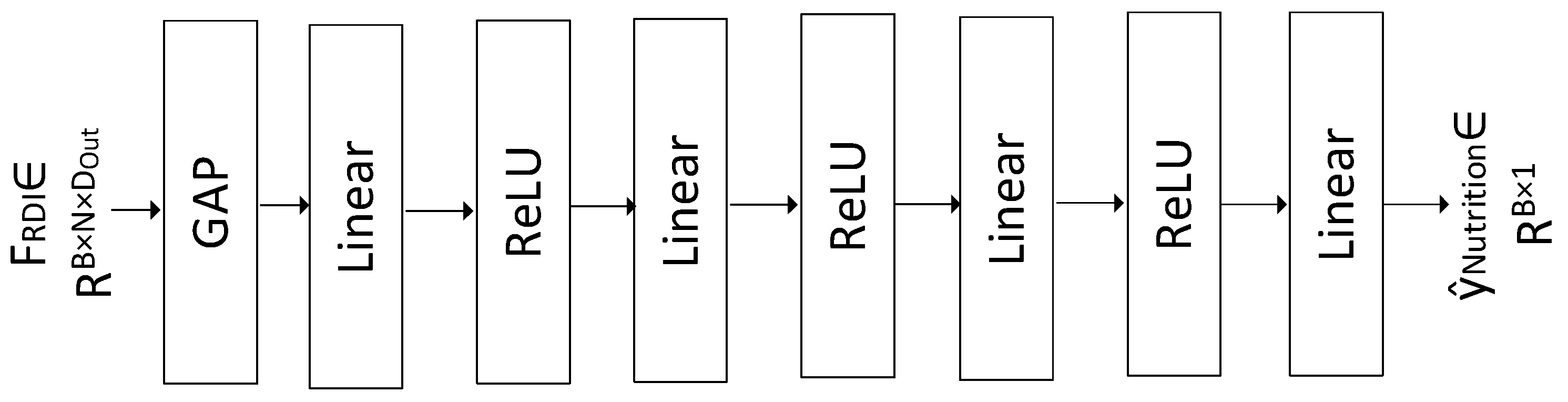

3.6. Nutrition Regressor

3.7. Loss Function

3.8. Evaluation Metrics

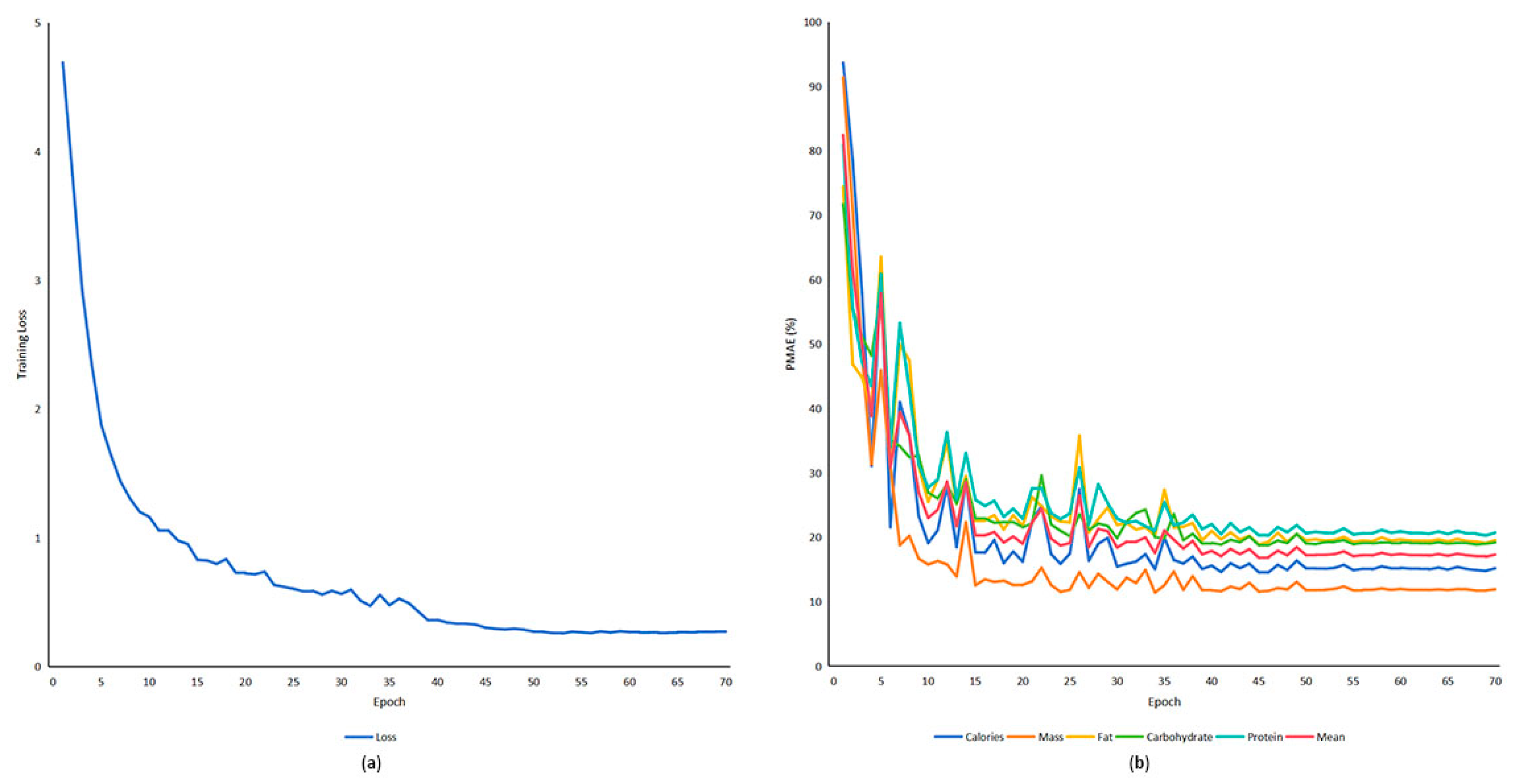

4. Results

4.1. Implementation Details

4.2. Experimental Results

4.3. Ablation Experiments

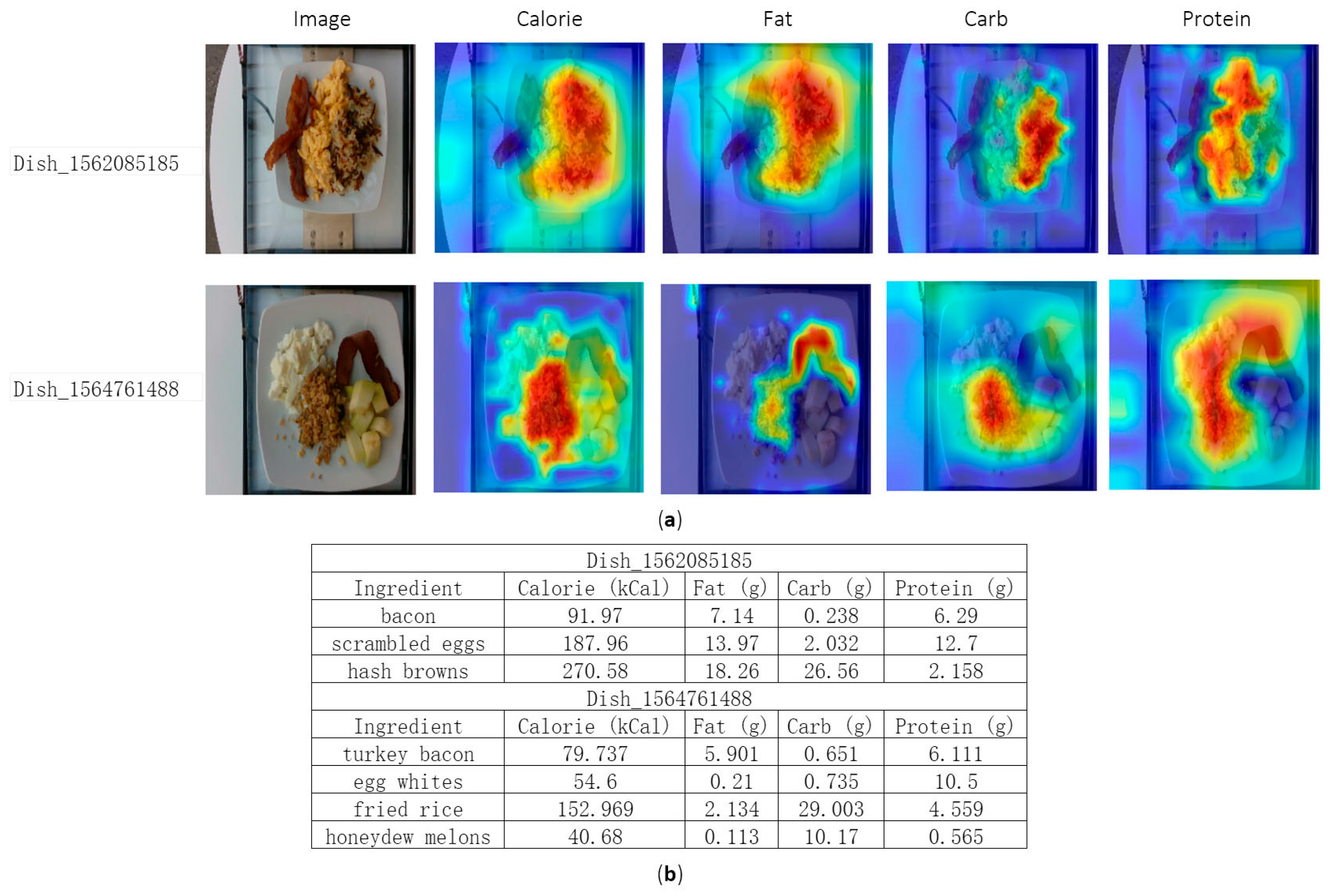

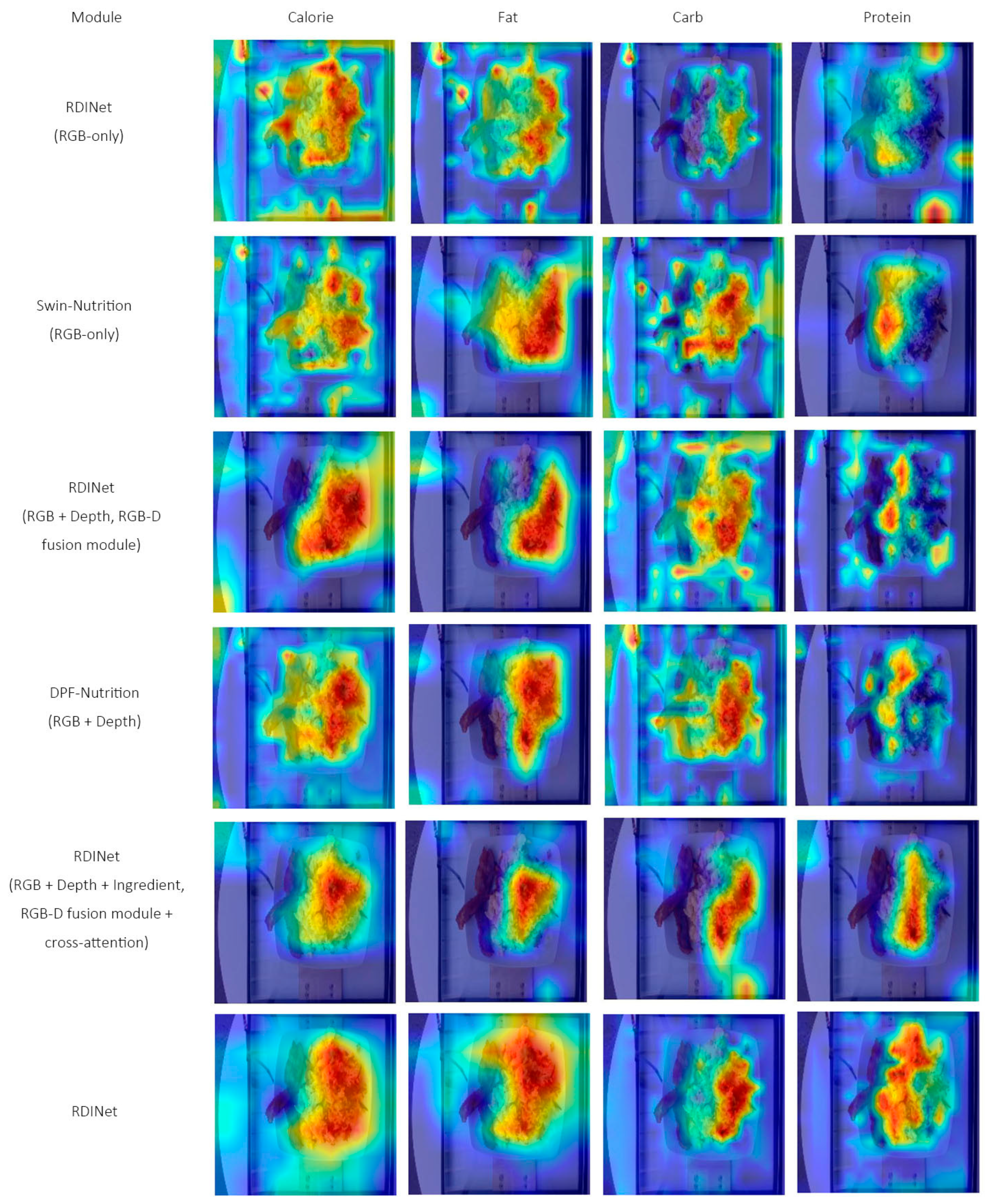

4.4. Visualization Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Black, R.E.; Victora, C.G.; Walker, S.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Christian, P.; De Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; et al. Maternal and Child Undernutrition and Overweight in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. Lancet 2013, 382, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Feng, Z.; Xiong, H.; Min, W.; Li, P.; Jiang, S. DSDGF-Nutri: A Decoupled Self-Distillation Network with Gating Fusion For Food Nutritional Assessment. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Dublin, Ireland, 27–31 October 2025; pp. 5218–5227. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W.C.; Sampson, L.; Stampfer, M.J.; Rosner, B.; Bain, C.; Witschi, J.; Hennekens, C.H.; Speizer, F.E. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1985, 122, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subar, A.F.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Mittl, B.; Zimmerman, T.P.; Thompson, F.E.; Bingley, C.; Willis, G.; Islam, N.G.; Baranowski, T.; McNutt, S.; et al. The Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour Dietary Recall (ASA24): A Resource for Researchers, Clinicians, and Educators from the National Cancer Institute. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 1134–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotwanvirat, P.; Prachansuwan, A.; Sridonpai, P.; Kriengsinyos, W. Advancements in Using AI for Dietary Assessment Based on Food Images: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e51432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albaladejo, L.; Giai, J.; Deronne, C.; Baude, R.; Bosson, J.-L.; Bétry, C. Assessing Real-Life Food Consumption in Hospital with an Automatic Image Recognition Device: A Pilot Study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2025, 68, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cofre, S.; Sanchez, C.; Quezada-Figueroa, G.; López-Cortés, X.A. Validity and Accuracy of Artificial Intelligence-Based Dietary Intake Assessment Methods: A Systematic Review. Br. J. Nutr. 2025, 133, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappan, A.; Bosch, M.; Zhu, F.; Boushey, C.J.; Kerr, D.A.; Ebert, D.S.; Delp, E.J. Personal Dietary Assessment Using Mobile Devices; Bouman, C.A., Miller, E.L., Pollak, I., Eds.; SPIE: San Jose, CA, USA, 2009; p. 72460Z. [Google Scholar]

- Ege, T.; Yanai, K. Multi-Task Learning of Dish Detection and Calorie Estimation. In Proceedings of the Joint Workshop on Multimedia for Cooking and Eating Activities and Multimedia Assisted Dietary Management, Stockholm, Sweden, 15 July 2018; pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Situju, S.F.; Takimoto, H.; Sato, S.; Yamauchi, H.; Kanagawa, A.; Lawi, A. Food Constituent Estimation for Lifestyle Disease Prevention by Multi-Task CNN. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2019, 33, 732–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Shao, Z.; Kerr, D.A.; Boushey, C.J.; Zhu, F. An End-to-End Image-Based Automatic Food Energy Estimation Technique Based on Learned Energy Distribution Images: Protocol and Methodology. Nutrients 2019, 11, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanail, I.; Vasiloglou, M.F.; Stathopoulou, T.; Ghosh, A.; Baumann, M.; Faeh, D.; Mougiakakou, S. A Feasibility Study to Assess Mediterranean Diet Adherence Using an AI-Powered System. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.; Tai, C.A.; Chen, Y.; Xi, P.; Wong, A. NutritionVerse-Direct: Exploring Deep Neural Networks for Multitask Nutrition Prediction from Food Images. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.07814. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; He, Y.; Khanna, N.; Boushey, C.J.; Delp, E.J. Model-Based Food Volume Estimation Using 3D Pose. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, Melbourne, Australia, 15–18 September 2013; pp. 2534–2538. [Google Scholar]

- Puri, M.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, Q.; Divakaran, A.; Sawhney, H. Recognition and Volume Estimation of Food Intake Using a Mobile Device. In Proceedings of the 2009 Workshop on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Snowbird, UT, USA, 7–8 December 2009; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.-C.; Jia, W.; Yue, Y.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.-N.; Fernstrom, J.D.; Sun, M. Model-Based Measurement of Food Portion Size for Image-Based Dietary Assessment Using 3D/2D Registration. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2013, 24, 105701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, A.; Johnston, N.; Rathod, V.; Korattikara, A.; Gorban, A.; Silberman, N.; Guadarrama, S.; Papandreou, G.; Huang, J.; Murphy, K. Im2Calories: Towards an Automated Mobile Vision Food Diary. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1233–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Stathopoulou, T.; Vasiloglou, M.F.; Christodoulidis, S.; Stanga, Z.; Mougiakakou, S. An Artificial Intelligence-Based System to Assess Nutrient Intake for Hospitalised Patients. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2021, 23, 1136–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thames, Q.; Karpur, A.; Norris, W.; Xia, F.; Panait, L.; Weyand, T.; Sim, J. Nutrition5k: Towards Automatic Nutritional Understanding of Generic Food. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 8899–8907. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, G.A.; Loo, C.K. A Comprehensive Survey of Image-Based Food Recognition and Volume Estimation Methods for Dietary Assessment. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, G.; Smailagic, A.; Siewiorek, D.P. Wearable Context-Aware Food Recognition for Calorie Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2008 12th IEEE International Symposium on Wearable Computers, Pittaburgh, PA, USA, 28 September–1 October 2008; pp. 119–120. [Google Scholar]

- Chotwanvirat, P.; Hnoohom, N.; Rojroongwasinkul, N.; Kriengsinyos, W. Feasibility Study of an Automated Carbohydrate Estimation System Using Thai Food Images in Comparison With Estimation by Dietitians. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 732449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruede, R.; Heusser, V.; Frank, L.; Roitberg, A.; Haurilet, M.; Stiefelhagen, R. Multi-Task Learning for Calorie Prediction on a Novel Large-Scale Recipe Dataset Enriched with Nutritional Information. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Milan, Italy, 10–15 January 2021; pp. 4001–4008. [Google Scholar]

- Kusuma, J.D.; Yang, H.-L.; Yang, Y.-L.; Chen, Z.-F.; Shiao, S.-Y.P.K. Validating Accuracy of a Mobile Application against Food Frequency Questionnaire on Key Nutrients with Modern Diets for mHealth Era. Nutrients 2022, 14, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Tran, L.M.; Hoang, N.T.; Trương, D.T.T.; Tran, T.H.T.; Huynh, P.N.; Koch, B.; McCloskey, P.; Gangupantulu, R.; Folson, G.; et al. Relative Validity of a Mobile AI-Technology–Assisted Dietary Assessment in Adolescent Females in Vietnam. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 116, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folson, G.K.; Bannerman, B.; Atadze, V.; Ador, G.; Kolt, B.; McCloskey, P.; Gangupantulu, R.; Arrieta, A.; Braga, B.C.; Arsenault, J.; et al. Validation of Mobile Artificial Intelligence Technology–Assisted Dietary Assessment Tool Against Weighed Records and 24-Hour Recall in Adolescent Females in Ghana. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 2328–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-A.; Huang, T.-T.; Yen, L.-H.; Wu, P.-H.; Chen, K.-W.; Kung, H.-H.; Liu, C.-Y.; Hsu, C.-Y. Precision Nutrient Management Using Artificial Intelligence Based on Digital Data Collection Framework. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Li, J. Computer Vision-Based Food Calorie Estimation: Dataset, Method, and Experiment. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.07632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; He, J.; Vinod, G.; Raghavan, S.; Czarnecki, C.; Ma, J.; Mahmud, T.I.; Coburn, B.; Mao, D.; Nair, S.; et al. MetaFood3D: 3D Food Dataset with Nutrition Values. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.01966. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Palsani, D.; Mondal, A.C. Nutritional Content Detection Using Vision Transformers- An Intelligent Approach. Int. J. Innov. Res. Eng. Manag. 2024, 11, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Gao, X.; Wang, X.; Deng, Z. Visual Transformers for Food Image Recognition: A Comprehensive Review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2503.18997. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, Y.; Ege, T.; Cho, J.; Yanai, K. DepthCalorieCam: A Mobile Application for Volume-Based FoodCalorie Estimation Using Depth Cameras. In Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on Multimedia Assisted Dietary Management, Nice, France, 21 October 2019; pp. 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Ng, A.B.; See, S. Nutrition Estimation for Dietary Management: A Transformer Approach with Depth Sensing. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2025, 27, 6047–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oquab, M.; Darcet, T.; Moutakanni, T.; Vo, H.; Szafraniec, M.; Khalidov, V.; Fernandez, P.; Haziza, D.; Massa, F.; El-Nouby, A.; et al. DINOv2: Learning Robust Visual Features without Supervision. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2304.07193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Wu, W.; Huang, Z. DPF-Nutrition: Food Nutrition Estimation via Depth Prediction and Fusion. Foods 2023, 12, 4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, W.; Min, W.; Hou, S.; Luo, M.; Li, T.; Zheng, Y.; Jiang, S. Vision-Based Food Nutrition Estimation via RGB-D Fusion Network. Food Chem. 2023, 424, 136309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2018, Proceedings of the 15th European Conference, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11211, pp. 3–19. ISBN 978-3-030-01233-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Enhancing Food Image Recognition by Multi-Level Fusion and the Attention Mechanism. Foods 2025, 14, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saffar, M.; Baiee, W.R. Nutrition Information Estimation from Food Photos Using Machine Learning Based on Multiple Datasets. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2022, 11, 2922–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhang, C.; Geng, B. Deep Multimodal Data Fusion. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, F. Multi-Modality Cross Attention Network for Image and Sentence Matching. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10938–10947. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Bu, T.; Hu, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X. Coarse-to-Fine Nutrition Prediction. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 3651–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image Is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Hou, S.; Jia, W.; Zheng, Y. Rapid Non-Destructive Analysis of Food Nutrient Content Using Swin-Nutrition. Foods 2022, 11, 3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.-P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. Pyramid Vision Transformer: A Versatile Backbone for Dense Prediction without Convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Categories | Samples | Image/Video | Depth | Ingredients | Nutrition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECUSTFD [28] | 19 | 2978 | Image | N | N | Mass |

| MetaFood3D [29] | 108 | 637 | Video | Y | N | Calories, Mass, Fat, Carbs and Protein |

| Nutrition5k [19] | 250 | 5006 | Image and Video | Y | Y | Calories, Mass, Fat, Carbs and Protein |

| Multimodal Data | Methods | Calorie PMAE (%) | Mass PMAE (%) | Fat PMAE (%) | Carb. PMAE (%) | Protein PMAE (%) | Mean PMAE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGB | Google-Nutrition-rgb [19] | 30.2 | 24.6 | 40.8 | 37.0 | 36.4 | 34.5 |

| Coarse-to-Fine Nutrition [44] | 29.4 | 25.7 | 42.2 | 38.3 | 39.8 | 35.1 | |

| ViT [45] | 25.6 | 21.4 | 37.6 | 33.2 | 34.9 | 30.5 | |

| Swin-Nutrition [46] | 23.7 | 19.8 | 32.4 | 29.4 | 31.7 | 27.4 | |

| RGB + Depth | Google-Nutrition-rgbd [19] | 23.4 | 23.7 | 25.1 | 30.4 | 25.2 | 25.6 |

| DPF-Nutrition [35] | 19.6 | 15.7 | 27.0 | 26.1 | 24.9 | 22.7 | |

| RGB-D Net [36] | 20.2 | 15.4 | 26.2 | 27.8 | 25.8 | 23.1 | |

| RGB + Depth + Ingredient | DSDGF-Nutri [2] | 16.2 | 11.8 | 24.5 | 22.4 | 22.9 | 19.6 |

| RDINet | 14.9 | 11.2 | 19.7 | 18.9 | 19.5 | 16.8 |

| Methods | Mass PMAE (%) |

|---|---|

| Google-Nutrition-rgb | 31.0 |

| Coarse-to-Fine Nutrition | 22.4 |

| ViT | 20.1 |

| Swin-Nutrition | 16.9 |

| RDINet (RGB-only) | 18.2 |

| Methods | Calorie PMAE (%) | Mass PMAE (%) | Fat PMAE (%) | Carb. PMAE (%) | Protein PMAE (%) | Mean PMAE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGB | 28.3 | 23.7 | 38.8 | 39.1 | 37.2 | 33.4 |

| Depth | 26.7 | 21.9 | 35.7 | 34.2 | 33.3 | 30.4 |

| RGB + Depth (channel attention) | 23.1 | 19.2 | 28.5 | 30.4 | 29.1 | 26.1 |

| RGB + Depth (spatial attention) | 24.0 | 20.1 | 29.7 | 31.2 | 30.3 | 27.1 |

| RGB + Depth (channel–spatial attention, RGB-D Fusion Module) | 21.5 | 17.3 | 25.8 | 28.3 | 26.7 | 23.9 |

| RGB + Depth + Ingredient (RGB-D Fusion Module + cross-attention) | 16.8 | 12.9 | 21.5 | 20.7 | 21.2 | 18.6 |

| RGB + Depth + Ingredient (RGB-D Fusion Module + self-attention) | 19.2 | 15.1 | 24.3 | 23.5 | 23.8 | 21.2 |

| RGB + Depth + Ingredient (RGB-D Fusion Module + cross-attention + self-attention, RGB-D Fusion Module + Ingredient Fusion Module) | 14.9 | 11.2 | 19.7 | 18.9 | 19.5 | 16.8 |

| Methods | Calorie PMAE (%) | Mass PMAE (%) | Fat PMAE (%) | Carb. PMAE (%) | Protein PMAE (%) | Mean PMAE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One layer (11) | 17.7 | 19.5 | 26.3 | 25.0 | 24.8 | 22.7 |

| Two layers (6, 11) | 15.9 | 13.9 | 23.8 | 22.8 | 23.2 | 19.9 |

| Thress layers (0, 6, 11) | 14.9 | 11.2 | 19.7 | 18.9 | 19.5 | 16.8 |

| Four layers (0, 4, 8, 11) | 14.6 | 11.1 | 19.9 | 19.3 | 19.8 | 16.9 |

| Methods | Calorie PMAE (%) | Mass PMAE (%) | Fat PMAE (%) | Carb. PMAE (%) | Protein PMAE (%) | Mean PMAE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGG16 | 22.0 | 17.8 | 28.4 | 30.2 | 25.1 | 24.7 |

| InceptionV3 | 21.8 | 17.1 | 26.0 | 28.8 | 24.3 | 23.6 |

| ResNet-18 | 21.3 | 16.7 | 25.8 | 27.4 | 24.1 | 23.1 |

| ResNet-50 | 20.9 | 16.4 | 25.7 | 26.8 | 23.6 | 22.7 |

| PVT | 16.2 | 13.2 | 23.3 | 24.6 | 22.4 | 19.9 |

| DINOv2 | 14.9 | 11.2 | 19.7 | 18.9 | 19.5 | 16.8 |

| Methods | Calorie PMAE (%) | Mass PMAE (%) | Fat PMAE (%) | Carb. PMAE (%) | Protein PMAE (%) | Mean PMAE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shared ingredient fusion | 17.1 | 13.1 | 25.3 | 24.7 | 23.6 | 20.8 |

| Separate ingredient fusion | 14.9 | 11.2 | 19.7 | 18.9 | 19.5 | 16.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kuang, Z.; Gao, H.; Yu, J.; Sun, D.; Zhao, J.; Sun, L. RDINet: A Deep Learning Model Integrating RGB-D and Ingredient Features for Food Nutrition Estimation. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010454

Kuang Z, Gao H, Yu J, Sun D, Zhao J, Sun L. RDINet: A Deep Learning Model Integrating RGB-D and Ingredient Features for Food Nutrition Estimation. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):454. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010454

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuang, Zhejun, Haobo Gao, Jiaxuan Yu, Dawen Sun, Jian Zhao, and Lei Sun. 2026. "RDINet: A Deep Learning Model Integrating RGB-D and Ingredient Features for Food Nutrition Estimation" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010454

APA StyleKuang, Z., Gao, H., Yu, J., Sun, D., Zhao, J., & Sun, L. (2026). RDINet: A Deep Learning Model Integrating RGB-D and Ingredient Features for Food Nutrition Estimation. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010454