Unveiling the Extremely Low Frequency Component of Heart Rate Variability

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Preprocessing

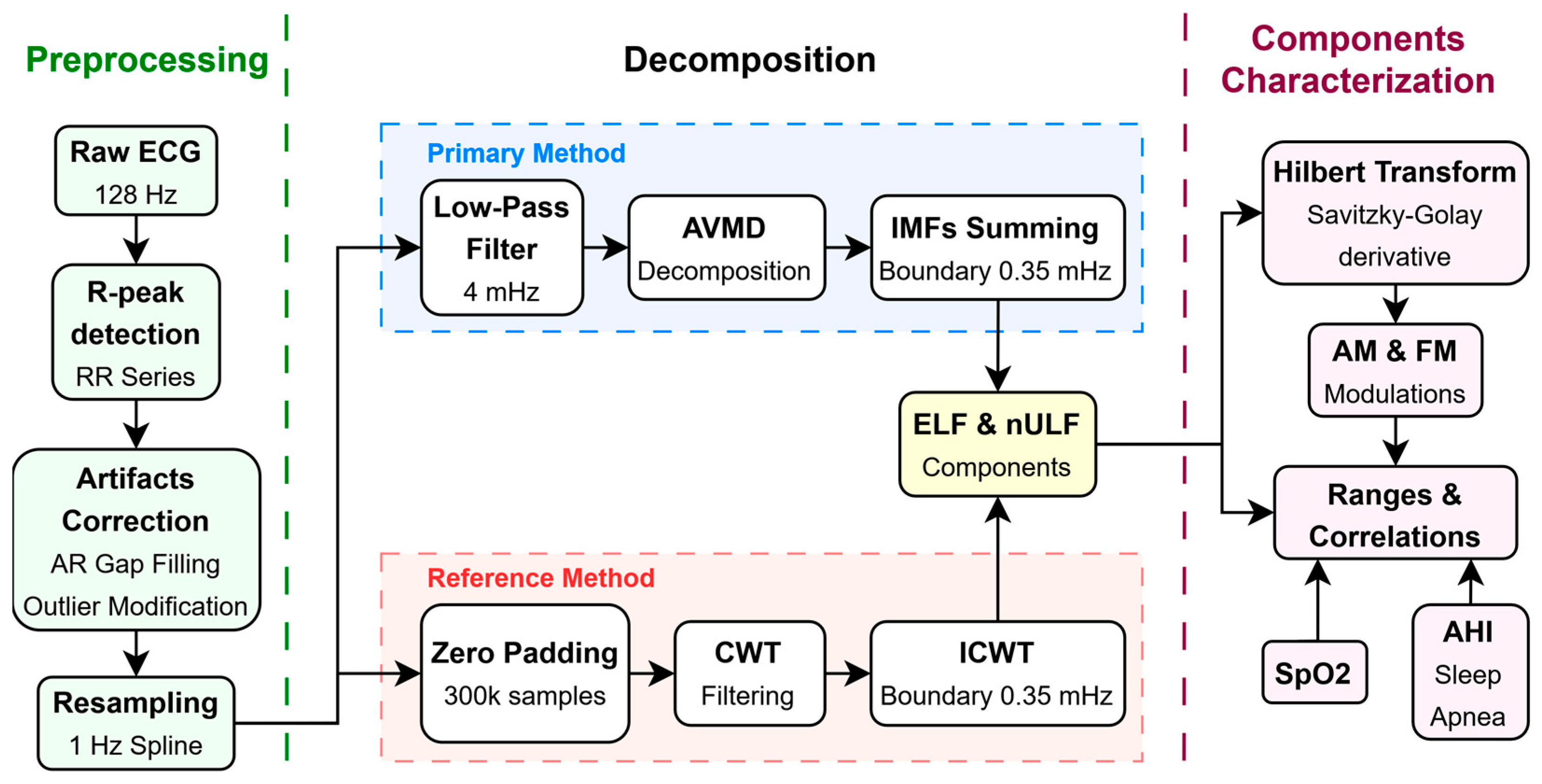

2.3. HRV Decomposition

2.4. Modulations Extraction

2.5. Analysis of ELF and nULF Properties

2.6. Coupling Between Analyzed Signals

3. Results

3.1. HRV Preprocessing

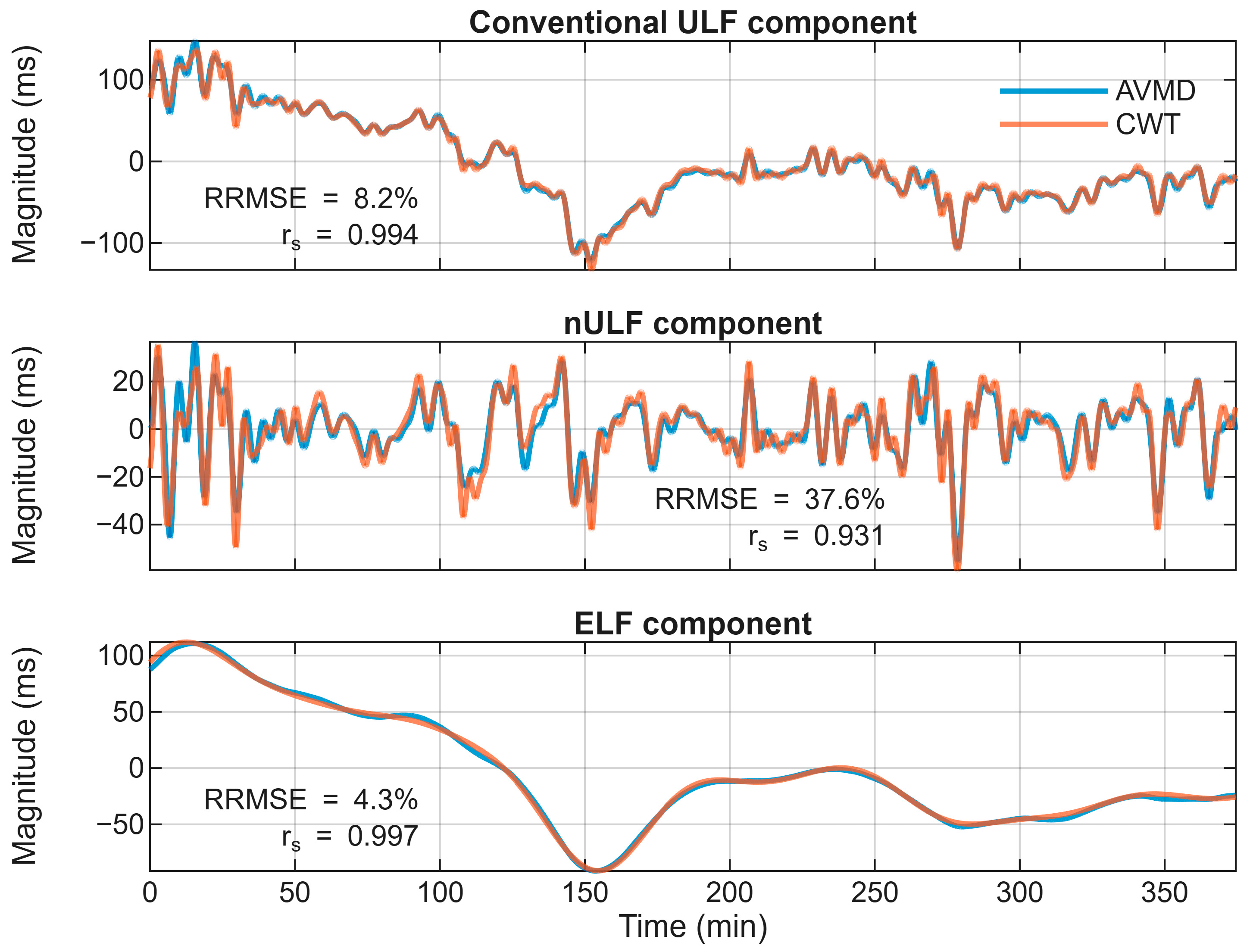

3.2. Extraction of ELF and nULF Components

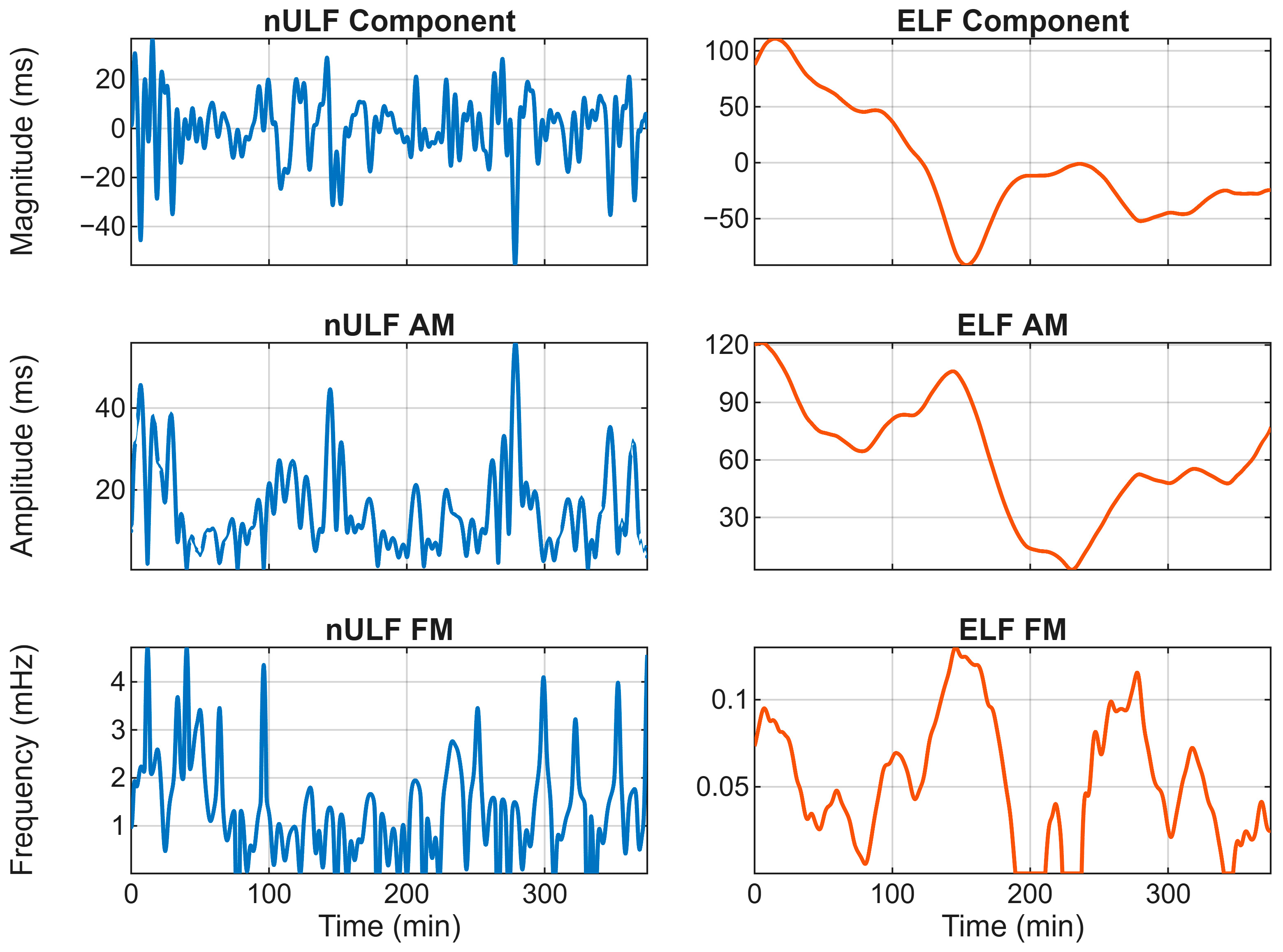

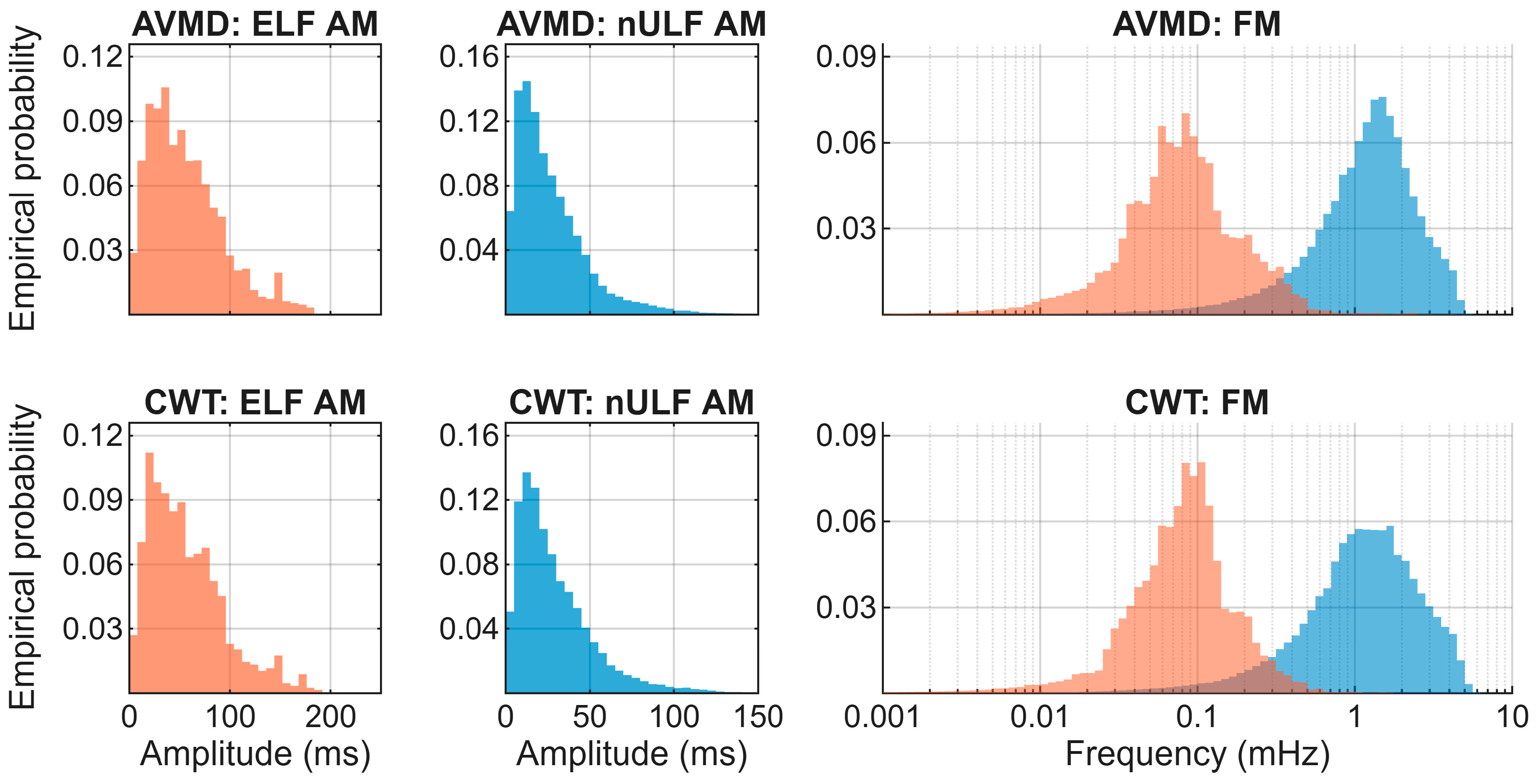

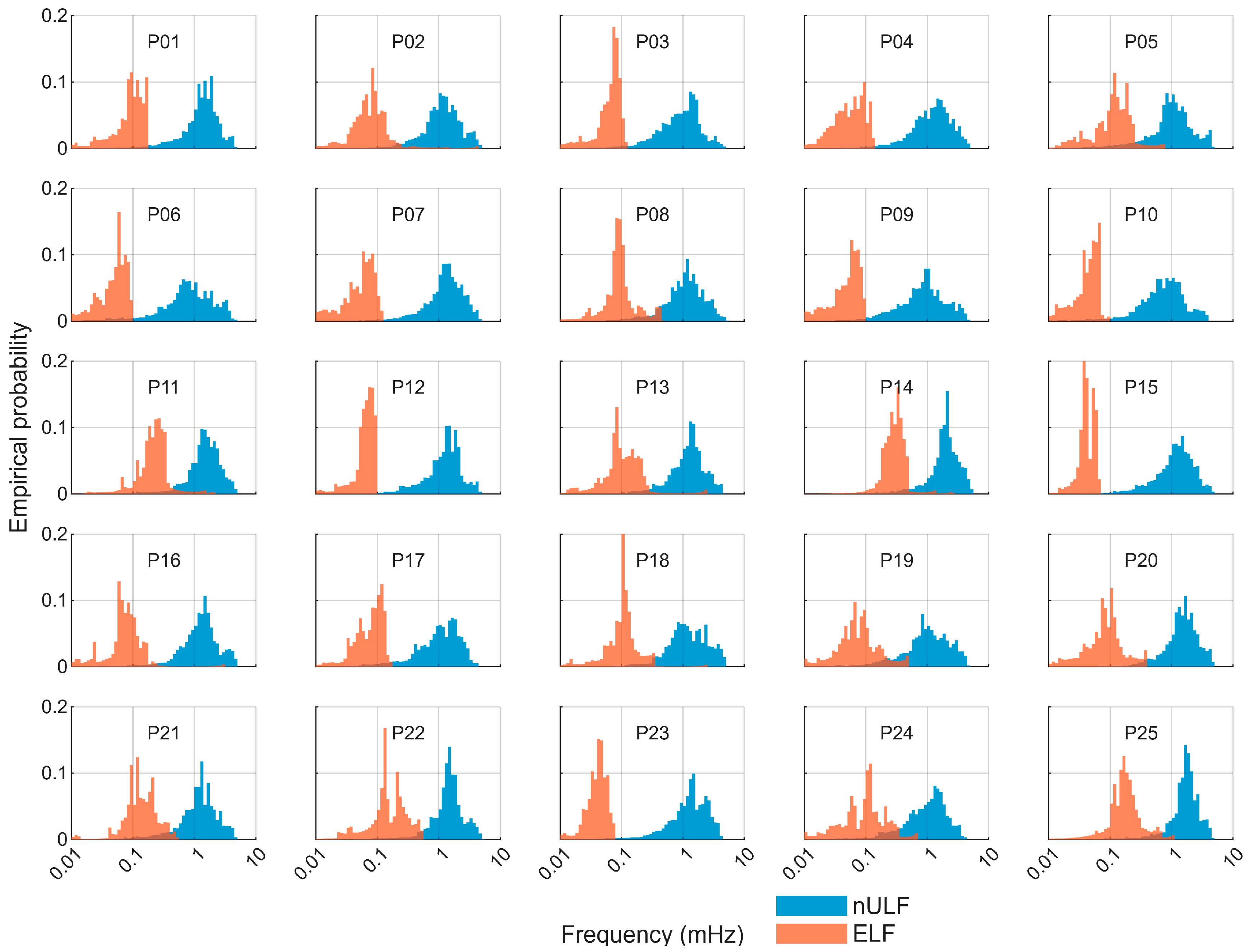

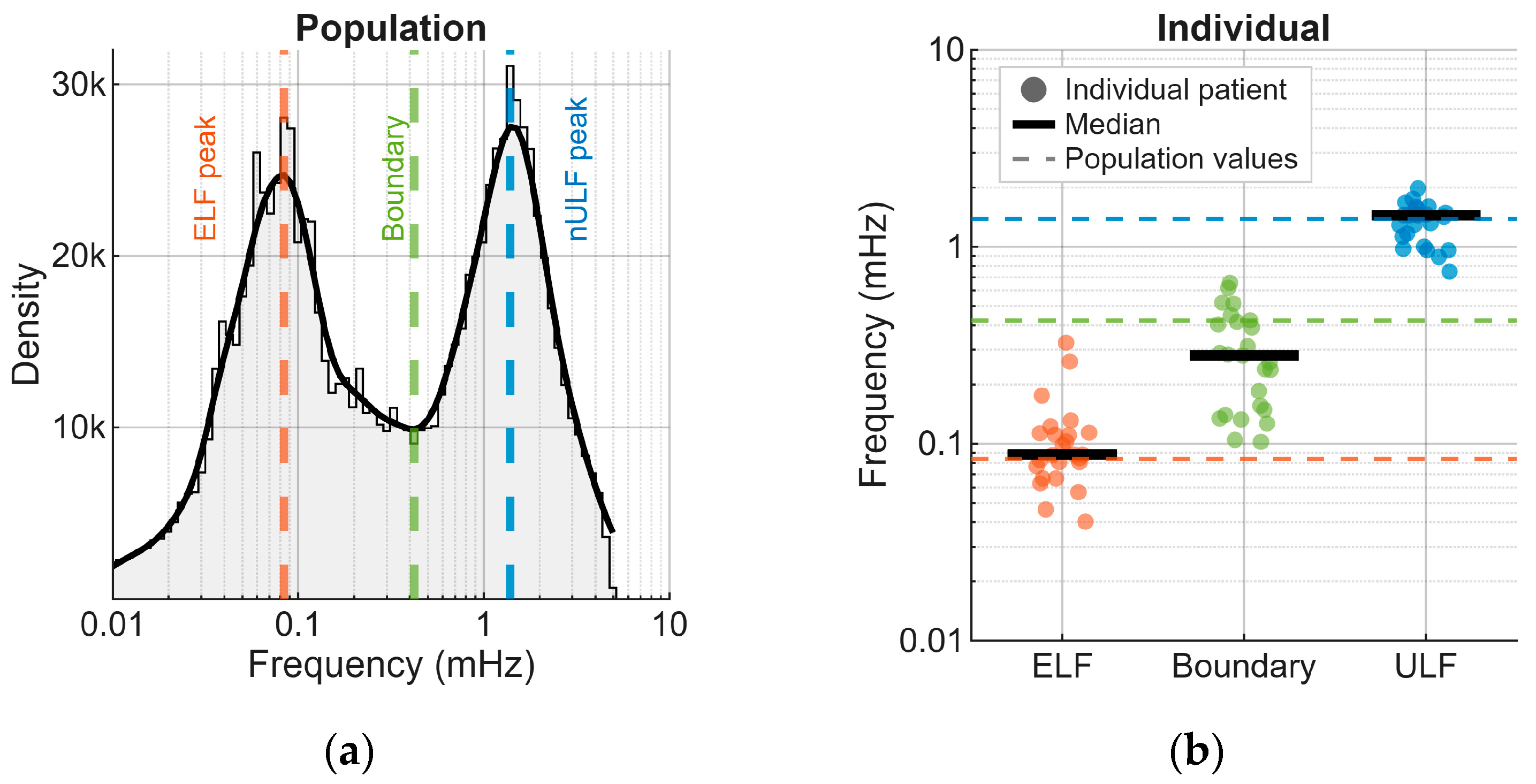

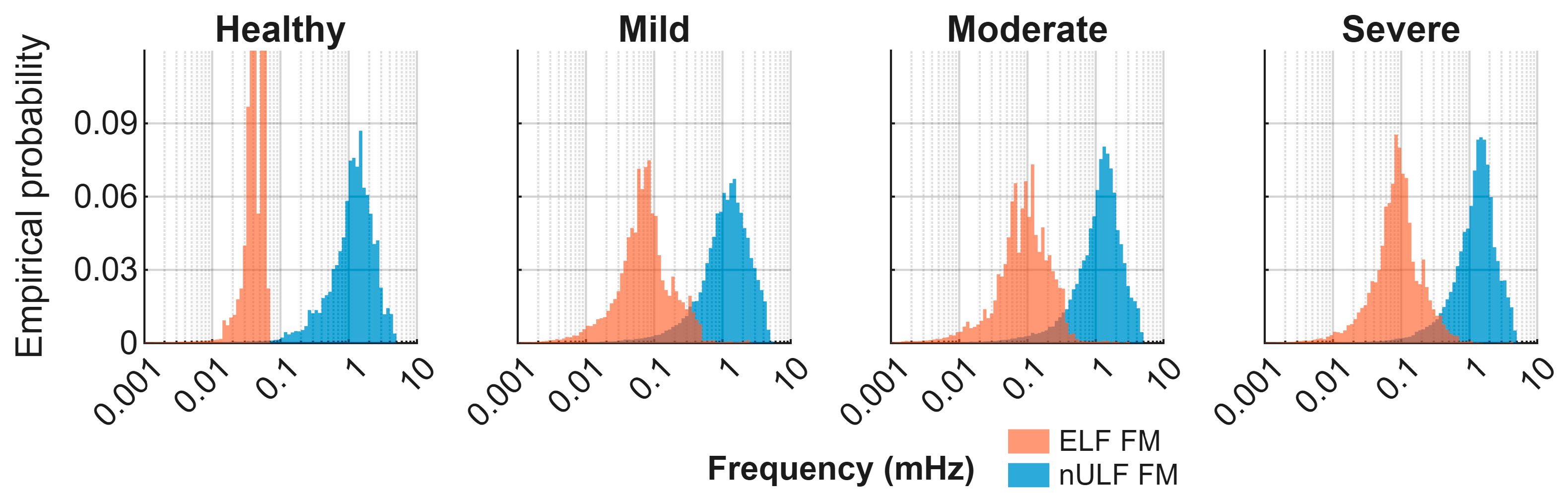

3.3. Properties of Extracted Components

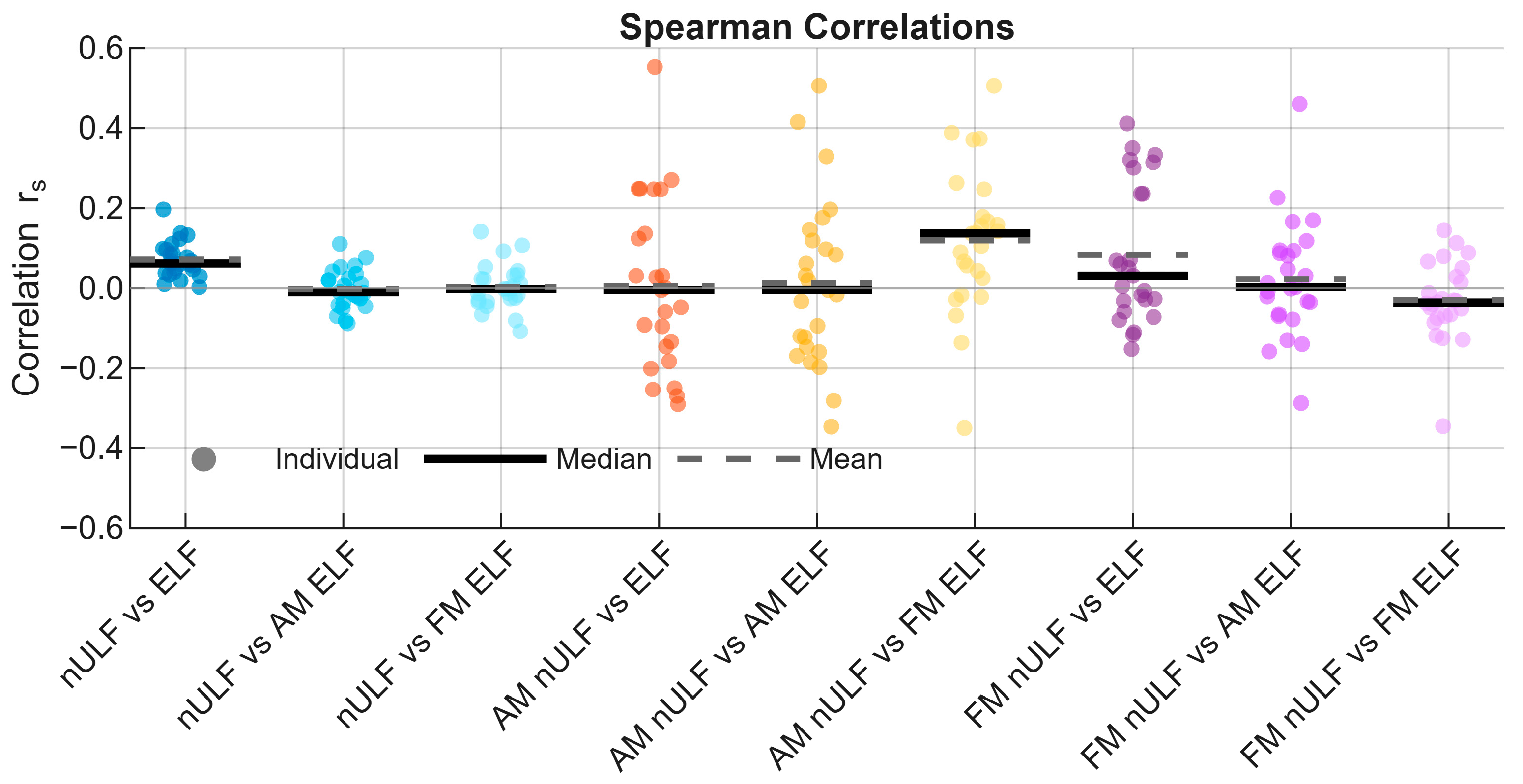

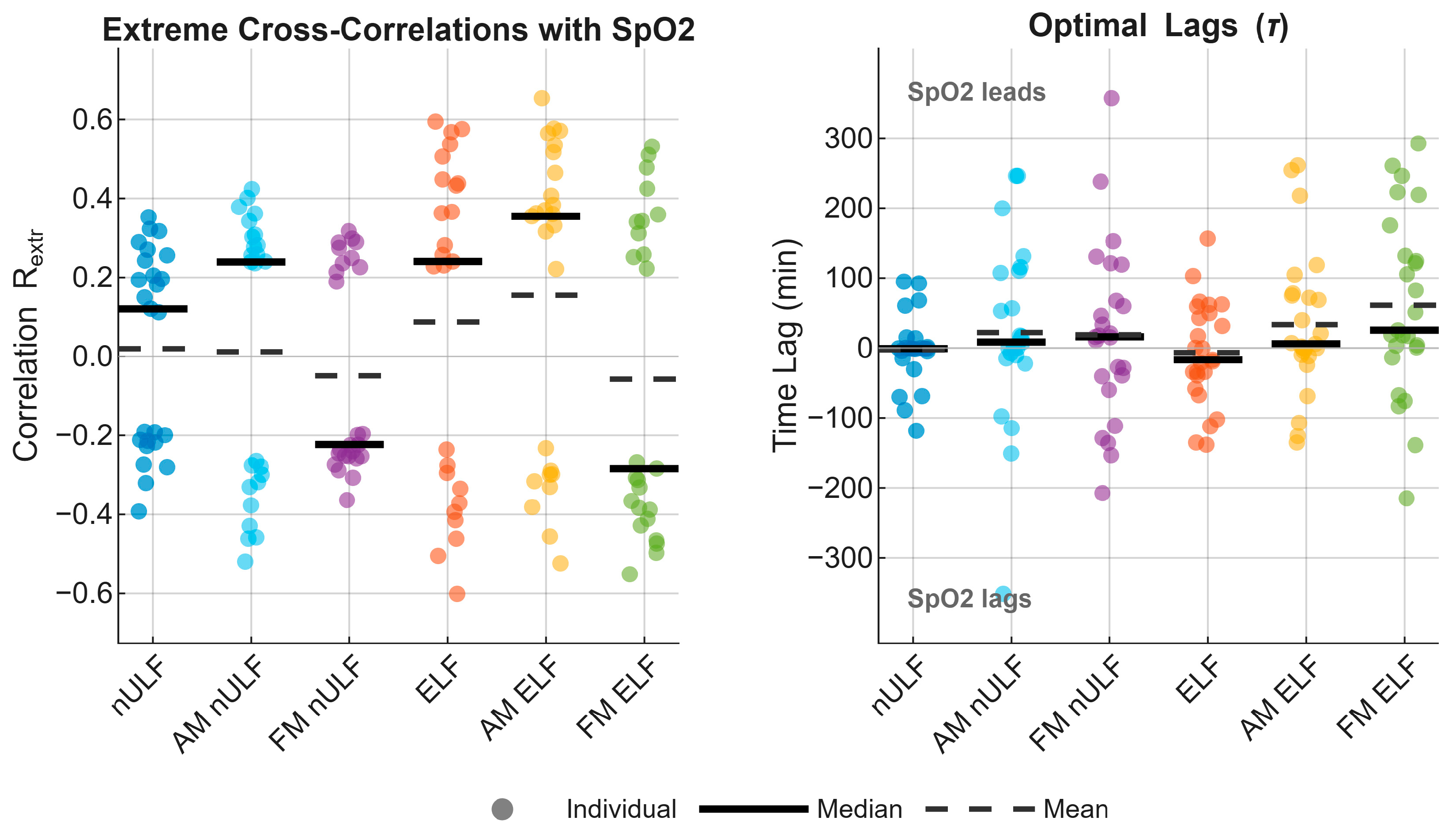

3.4. Correlations

4. Discussion

4.1. Novelty of the Work

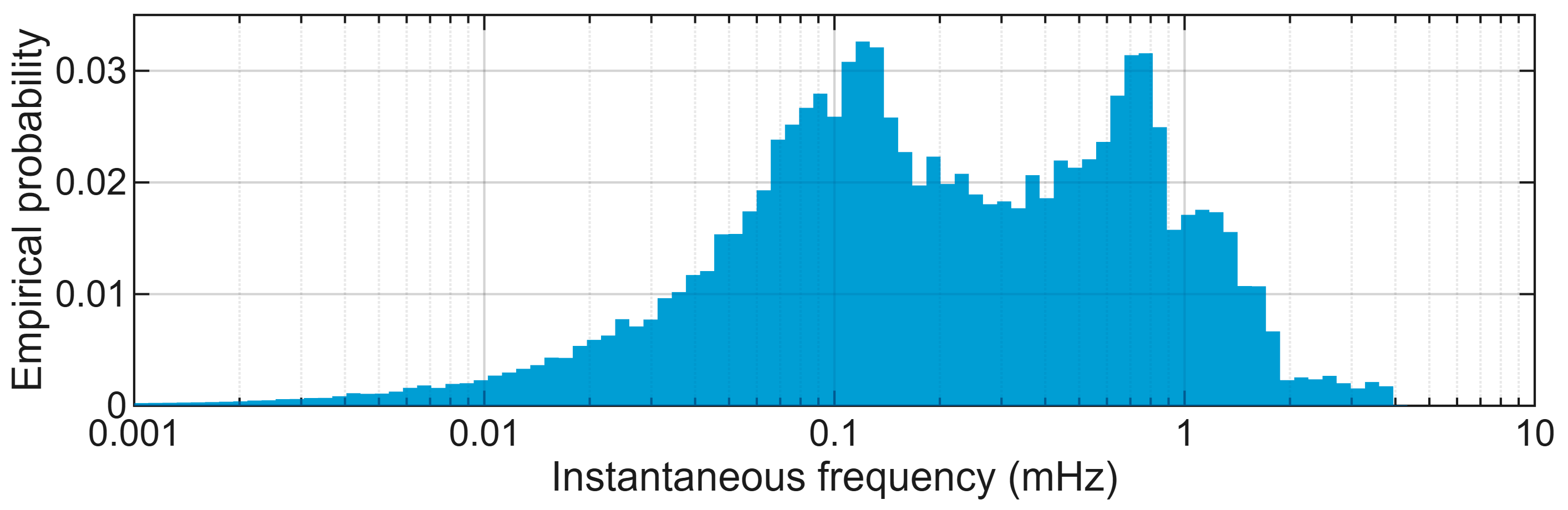

4.2. Bimodality of the Conventional ULF Component

4.3. Amplitude and Frequency Properties of ELF and nULF

4.4. Relationships of ELF and nULF to Physiological Processes

4.5. Limitations of the Work and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHI | Apnea-Hypopnea Index |

| AM | Amplitude Modulation |

| ANS | Autonomic Nervous System |

| AVMD | Adaptive Variational Mode Decomposition |

| BLG | Blood Glucose Level |

| BPV | Blood Pressure Variability |

| CGM | Continuous Glucose Monitoring |

| CWT | Continuous Wavelet Transform |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| EDA | Electrodermal Activity |

| ELF | Extremely Low Frequency |

| EMG | Electromyogram |

| EOG | Electrooculogram |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| FM | Frequency Modulation |

| HF | High Frequency |

| HRV | Heart Rate Variability |

| HT | Hilbert Transform |

| ICWT | Inverse Continuous Wavelet Transform |

| IMF | Intrinsic Mode Function |

| LF | Low Frequency |

| nULF | Narrowed Ultra-low Frequency |

| PPG | Photoplethysmogram |

| PSG | Polysomnography |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RRMSE | Relative Root Mean Square Error |

| SAS | Sleep Apnea Syndrome |

| SGF | Savitzky–Golay Filter |

| SpO2 | Peripheral Oxygen Saturation |

| ULF | Ultra-low Frequency |

| VLF | Very Low Frequency |

References

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieciński, S.; Kostka, P.S.; Tkacz, E.J. Heart rate variability analysis on electrocardiograms, seismocardiograms and gyrocardiograms on healthy volunteers. Sensors 2020, 20, 4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbimbo, C.; Spallazzi, M.; Ferrari-Pellegrini, F.; Villa, A.; Zilioli, A.; Mutti, C.; Parrino, L.; Lazzeroni, D. Heart rate variability and cognitive performance in adults with cardiovascular risk. Cereb. Circ.-Cogn. Behav. 2022, 3, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejía-Mejía, E.; Kyriacou, P.A. Photoplethysmography-Based Pulse Rate Variability and Haemodynamic Changes in the Absence of Heart Rate Variability: An In-Vitro Study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieciński, S.; Tkacz, E.J.; Kostka, P.S. Heart rate variability analysis on electrocardiograms, seismocardiograms and gyrocardiograms of healthy volunteers and patients with valvular heart diseases. Sensors 2023, 23, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regueiro-Oliveira, O.L.; Osorio-Romero, L.F.; Sanchez-Mendez, L.D. Which indices of heart rate variability are the best predictors of mortality after acute myocardial infarction? Meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Electrocardiol. 2024, 84, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva-Tsaneva, G.; Lebamovski, P.; Tsanev, Y.-A. Impact of Prolonged High-Intensity Training on Autonomic Regulation and Fatigue in Track and Field Athletes Assessed via Heart Rate Variability. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelushi, A.M.; Manathunga, C.H.; Gamage, N.G.S.S.; Nakayama, T. Assessing Cardiac Sympatho-Vagal Balance Through Wavelet Transform Analysis of Heart Rate Variability. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, S.; Ferrero, R.; Pegoraro, P.A.; Toscani, S. Application of Taylor-Fourier Analysis to Photoplethysmography Signals for Instantaneous Heart Rate Measurement. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 4019414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uryga, A.; Olszewski, B.; Pietroń, D.; Kasprowicz, M. Impact of signal length and window size on heart rate variability and pulse rate variability metrics. Physiol. Meas. 2025, 46, 075006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuda, E.; Yoshida, Y. Influence of Posture and Sleep Duration on Heart Rate Variability in Older Subjects. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyono, K.; Hayano, J.; Kwak, S.; Watanabe, E.; Yamamoto, Y. Non-Gaussianity of low frequency heart rate variability and sympathetic activation: Lack of increases in multiple system atrophy and Parkinson disease. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, P.F.; Miller, D.P.; Allen, M.T.; Handy, J.D.; Servatius, R.J. Cardiorespiratory Response to Moderate Hypercapnia in Female College Students Expressing Behaviorally Inhibited Temperament. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 588813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, K.; Polak, A.G. Comparison of multiband filtering, empirical mode decomposition and short-time Fourier transform used to extract physiological components from long-term heart rate variability. Metrol. Meas. Syst. 2021, 28, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, K.; Polak, A.G. Derivation of frequency components from overnight heart rate variability using an adaptive variational mode decomposition. In Proceedings of the 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Mexico City, Mexico, 1–5 November 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, A.G.; Klich, B.; Saganowski, S.; Prucnal, M.A.; Kazienko, P. Processing photoplethysmograms recorded by smartwatches to improve the quality of derived pulse rate variability. Sensors 2022, 22, 7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, K.; Polak, A.G. Online Algorithm for Deriving Heart Rate Variability Components and Their Time–Frequency Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prucnal, M.A.; Polak, A.G.; Kazienko, P. Improving the quality of pulse rate variability derived from wearable devices using adaptive, spectrum and nonlinear filtering. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 102, 107336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Mejía, E.; Kyriacou, P.A. Duration of photoplethysmographic signals for the extraction of Pulse Rate Variability Indices. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 80, 104214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panday, K.R.; Panday, D.R. Heart Rate Variability (HRV). J. Clin. Exp. Cardiol. 2018, 9, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberger, A.L.; Amaral, L.A.; Glass, L.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Ivanov, P.C.; Mark, R.G.; Mietus, J.E.; Moody, G.B.; Peng, C.K.; Stanley, H.E. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: Components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. Circulation 2000, 101, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropotov, J.D. The enigma of infra-slow fluctuations in the human EEG. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 928410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltola, M.E.; Leitinger, M.; Halford, J.J.; Vinayan, K.P.; Kobayashi, K.; Pressler, R.M.; Mindruta, I.; Mayor, L.C.; Lauronen, L.; Beniczky, S. Routine and sleep EEG: Minimum recording standards of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology and the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2023, 64, 602–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liliefors, H.W. On the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test for Normality with Mean and Variance Unknown. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1967, 62, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesaragi, N.P.; Sharma, A.; Patidar, S.; Acharya, U.R. Automated diagnosis of coronary artery disease using scalogram-based tensor decomposition with heart rate signals. Med. Eng. Phys. 2022, 110, 103811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savitzky, A.; Golay, M.J.E. Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures. Anal. Chem. 1964, 36, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.; Rath, D.; Diebold, U. Why and How Savitzky–Golay Filters Should Be Replaced. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2022, 2, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-K.; Sheu, J.-C.; Hsue, C. Overcoming the negative frequencies-instantaneous frequency and amplitude estimation using osculating circle method. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2011, 19, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.D. Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences; Brooks/Cole Publishing: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, L.J.; Kristo, D.; Strollo, P.J.; Friedman, N.; Malhotra, A.; Patil, S.P.; Ramar, K.; Rogers, R.; Schwab, R.J.; Weaver, E.M.; et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2009, 5, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, M.H.; Maywood, E.S.; Brancaccio, M. Generation of circadian rhythms in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijk, D.J.; Landolt, H.P. Sleep physiology, circadian rhythms, waking performance and the development of sleep-wake therapeutics. In Sleep-Wake Neurobiology and Pharmacology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 441–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, S.; Takaoka, Y.; Toyoura, M.; Kohira, S.; Ohta, M. Core body temperature changes in school-age children with circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorder. Sleep Med. 2021, 87, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refinetti, R. Circadian rhythmicity of body temperature and metabolism. Temperature 2020, 7, 321–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martchenko, A.; Martchenko, S.E.; Biancolin, A.D.; Brubaker, P.L. Circadian rhythms and the gastrointestinal tract: Relationship to metabolism and gut hormones. Endocrinology 2020, 161, bqaa167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begemann, K.; Rawashdeh, O.; Olejniczak, I.; Pilorz, V.; de Assis, L.V.M.; Osorio-Mendoza, J.; Oster, H. Endocrine regulation of circadian rhythms. Npj Biol. Timing Sleep 2025, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerkema, M.P. Ultradian rhythms. In Biological Rhythms; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.D.; Wilsterman, K.; Smarr, B.L.; Kriegsfeld, L.J. Evidence for a coupled oscillator model of endocrine ultradian rhythms. J. Biol. Rhythms 2018, 33, 475–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalafatakis, K.; Russell, G.M.; Lightman, S.L. MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY: Does circadian and ultradian glucocorticoid exposure affect the brain? Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 180, R73–R89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lightman, S.L.; Conway-Campbell, B.L. Circadian and ultradian rhythms: Clinical implications. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 296, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.D.; Newman, M.; Kriegsfeld, L.J. Ultradian rhythms in heart rate variability and distal body temperature anticipate onset of the luteinizing hormone surge. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannahoff-Khalsa, D.; Schult, R.; Sramek, B.B. Ultradian Hemodynamics and Autonomic-Central Nervous System Activity During Sleep: A Pilot Study with Insights for Hypertension. Integr. Med. Rep. 2022, 1, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blessing, W.W. Thermoregulation and the ultradian basic rest–activity cycle. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 156, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, E.; Le, T.D.; Jouvet, P.; Noumeir, R. Heart rate and body temperature relationship in children admitted to PICU-A machine learning approach. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 72, 2352–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S.L.; Wood, S.; Koshiaris, C.; Law, K.; Glasziou, P.; Stevens, R.J.; McManus, R.J. Blood pressure variability and cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2016, 354, i4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narita, K.; Hoshide, S.; Kario, K. Short-to long-term blood pressure variability: Current evidence and new evaluations. Hypertens. Res. 2023, 46, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, A.; Rawal, K. A review on physiological signals: Heart rate variability and skin conductance. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computing, Communications, and Cyber-Security (IC4S 2019), Gdańsk, Poland, 12–13 October 2019; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechyporenko, A.; Frohme, M.; Strelchuk, Y.; Omelchenko, V.; Gargin, V.; Ishchenko, L.; Alekseeva, V. Galvanic Skin Response and Photoplethysmography for Stress Recognition Using Machine Learning and Wearable Sensors. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarman, L.R.; Elliott, J.L.; Lees, T.; Clifton-Bligh, R.; Simpson, A.M.; Nassif, N.; Lal, S. Heart rate variability as a potential non-invasive marker of blood glucose level. Hum. Physiol. 2021, 47, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansukhani, M.P.; Kara, T.; Caples, S.M.; Somers, V.K. Chemoreflexes, sleep apnea, and sympathetic dysregulation. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2014, 16, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labarca, G.; Gower, J.; Lamperti, L.; Dreyse, J.; Jorquera, J. Chronic intermittent hypoxia in obstructive sleep apnea: A narrative review from pathophysiological pathways to a precision clinical approach. Sleep Breath. 2020, 24, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccoli, G.; Amici, R. Sleep and autonomic nervous system. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2020, 15, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, M.J.; Wallace, D.A.; Purcell, S.; Sofer, T. Reproducibility in computational sleep research: A call for action. Sleep 2024, 47, zsad143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, V.C.C.; Bandeira, P.M.; Azevedo, J.C.M. Heart rate variability in adults with obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review. Sleep Sci. 2019, 12, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M.; Altin, R.; Ozeren, A.; Kart, L.; Bilge, M.; Unalacak, M. Cardiac autonomic activity in obstructive sleep apnea: Time-dependent and spectral analysis of heart rate variability using 24-hour Holter electrocardiograms. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2004, 31, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, S.; Wu, H.W.; Hwang, G.S.; Kim, H.J. Clinical implication of heart rate variability in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome patients. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2015, 26, 1592–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, A.; Hayano, J.; Ito, N.; Miyata, S.; Yasuma, F.; Yasuda, Y. Very low frequency component of heart rate variability as a marker for therapeutic efficacy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: Preliminary study. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2019, 24, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attar, E.T. Detailed evaluation of sleep apnea using heart rate variability: A machine learning and statistical method using ECG data. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1636983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polak, A.G.; Prucnal, M.A.; Adamczyk, K. Analysis of the Relationship Between Electrodermal Activity and Blood Glucose Level in Diabetics. In Proceedings of the International Work-Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering, Cham, Switzerland, 15–17 July 2024; pp. 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | RRMSE (%) Mean ± SD | rs Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| ULF | 13.7 ± 4.4 | 0.998 ± 0.007 |

| nULF | 34.2 ± 9.4 | 0.930 ± 0.042 |

| ELF | 13.2 ± 10.7 | 0.979 ± 0.028 |

| Central Interval | ELF AM (ms) | nULF AM (ms) | ELF FM (mHz) | nULF FM (mHz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% | 7.4–149 | 3.2–88 | 0.009–0.396 | 0.11–3.88 |

| 99% | 2.9–173 | 1.5–125 | 0.002–0.874 | 0.02–4.49 |

| Parameter | Population Based (mHz) | Individual Median (mHz) | Individual Range (mHz) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ELF Peak | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.04–0.33 |

| Boundary | 0.42 | 0.28 | 0.10–0.66 |

| nULF Peak | 1.39 | 1.44 | 0.75–1.98 |

| Apnea Severity | AHI Range | No. of Patients | ELF FM (mHz) | nULF FM (mHz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | <5 | 1 | 0.015–0.062 | 0.14–3.69 |

| Mild | 5–15 | 10 | 0.008–0.407 | 0.09–3.95 |

| Moderate | 15–30 | 6 | 0.008–0.365 | 0.10–3.81 |

| Severe | ≥30 | 8 | 0.011–0.414 | 0.16–3.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Adamczyk, K.; Polak, A.G. Unveiling the Extremely Low Frequency Component of Heart Rate Variability. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010426

Adamczyk K, Polak AG. Unveiling the Extremely Low Frequency Component of Heart Rate Variability. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):426. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010426

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdamczyk, Krzysztof, and Adam G. Polak. 2026. "Unveiling the Extremely Low Frequency Component of Heart Rate Variability" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010426

APA StyleAdamczyk, K., & Polak, A. G. (2026). Unveiling the Extremely Low Frequency Component of Heart Rate Variability. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010426