Productivity Simulation of Multilayer Commingled Production in Deep Coalbed Methane Reservoirs: A Coupled Stress-Desorption-Flow Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

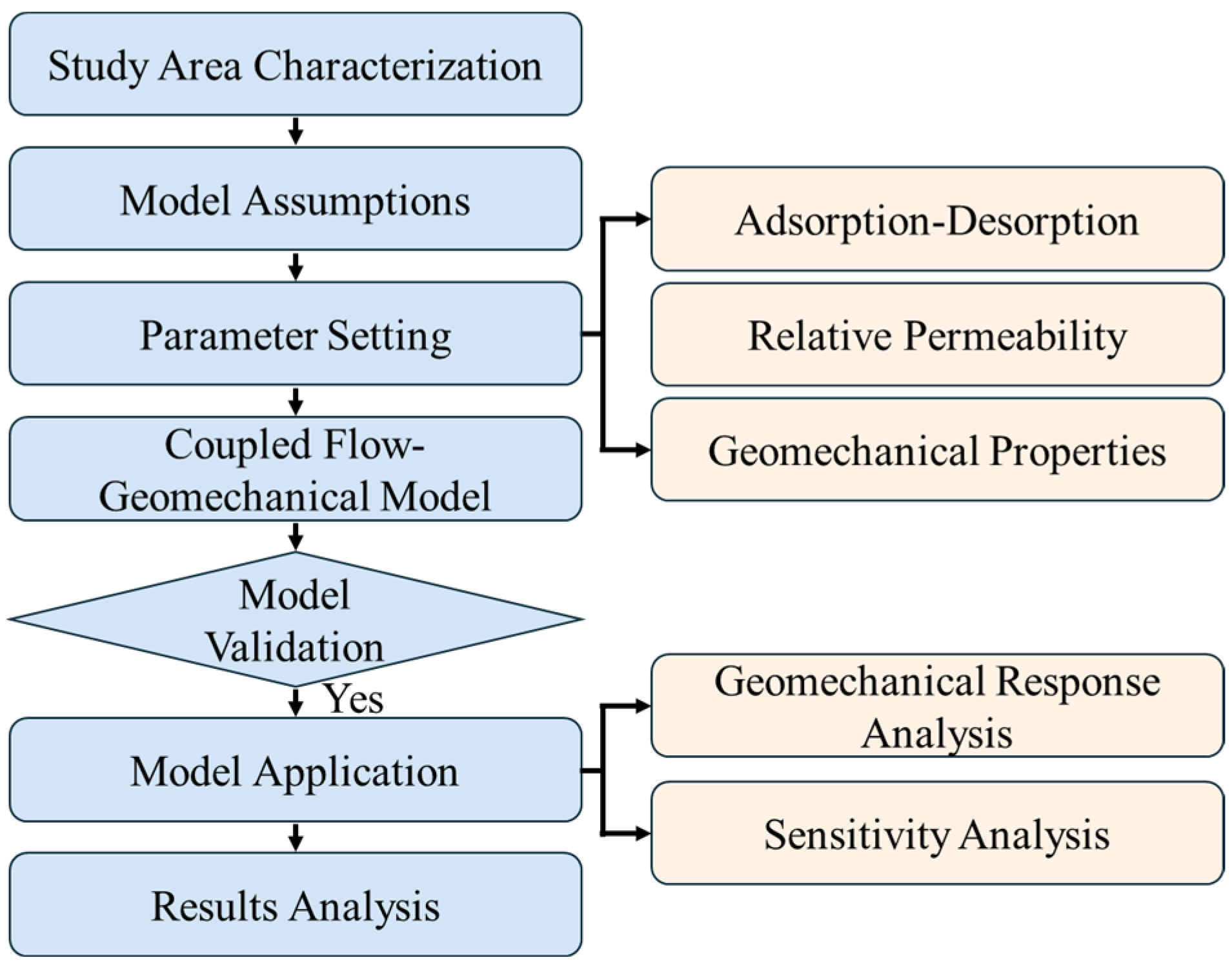

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Regional Overview

2.2. Experimental Material

2.3. Model Assumptions

2.4. Parameter Setting

2.4.1. Relative Permeability Data

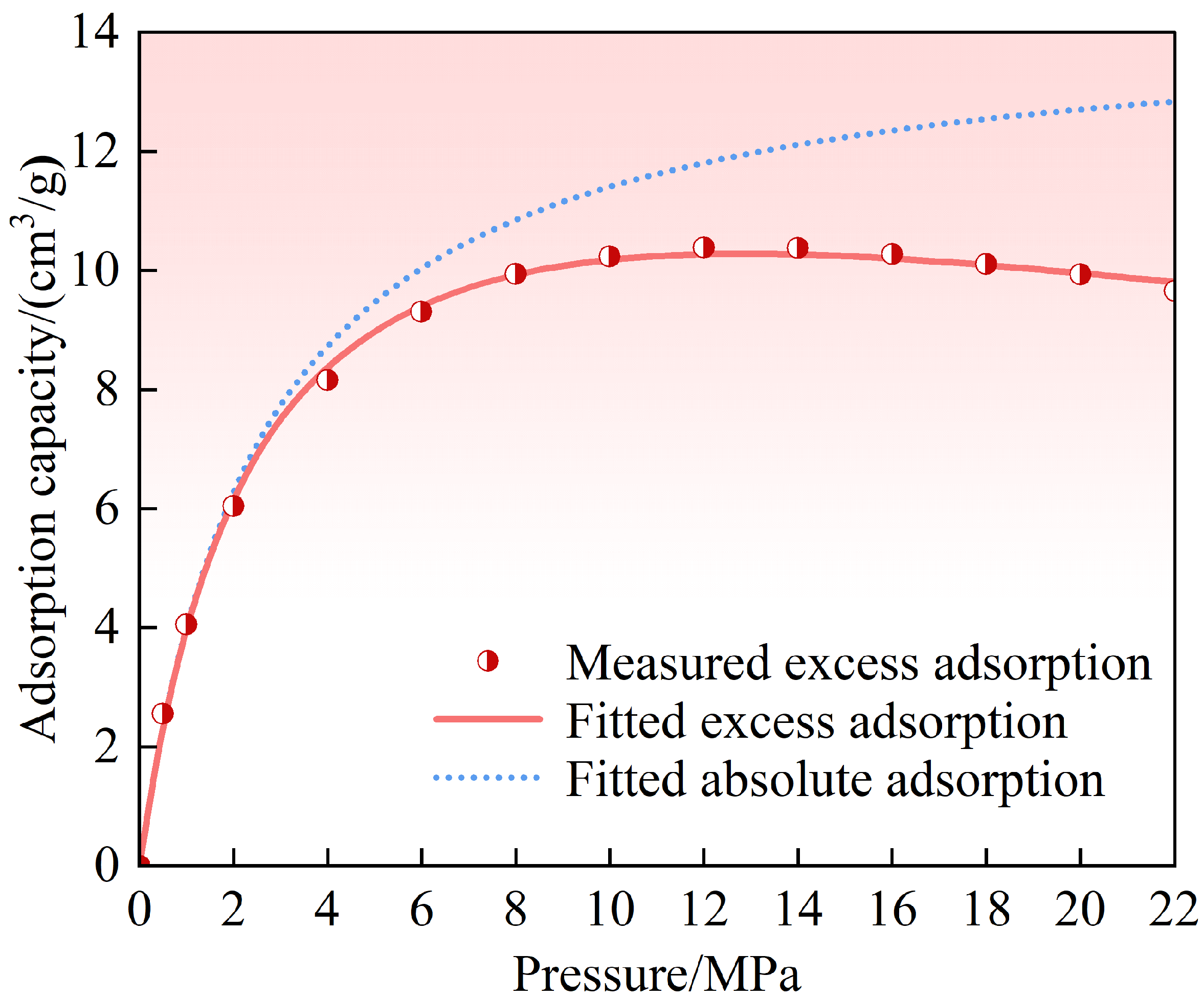

2.4.2. Methane Adsorption–Desorption Parameters

2.4.3. Geomechanical Properties

2.5. Model Validation

3. Results and Analysis

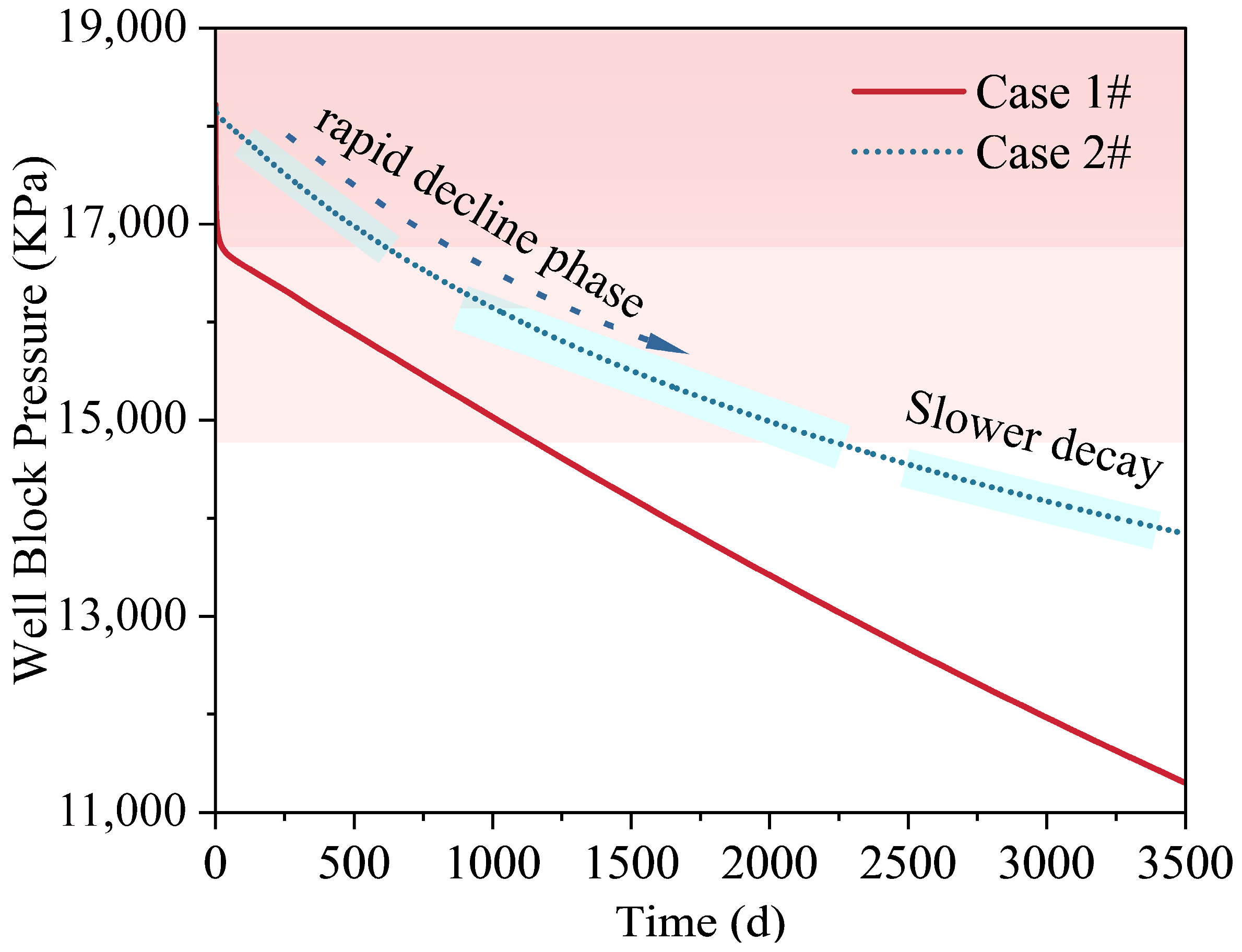

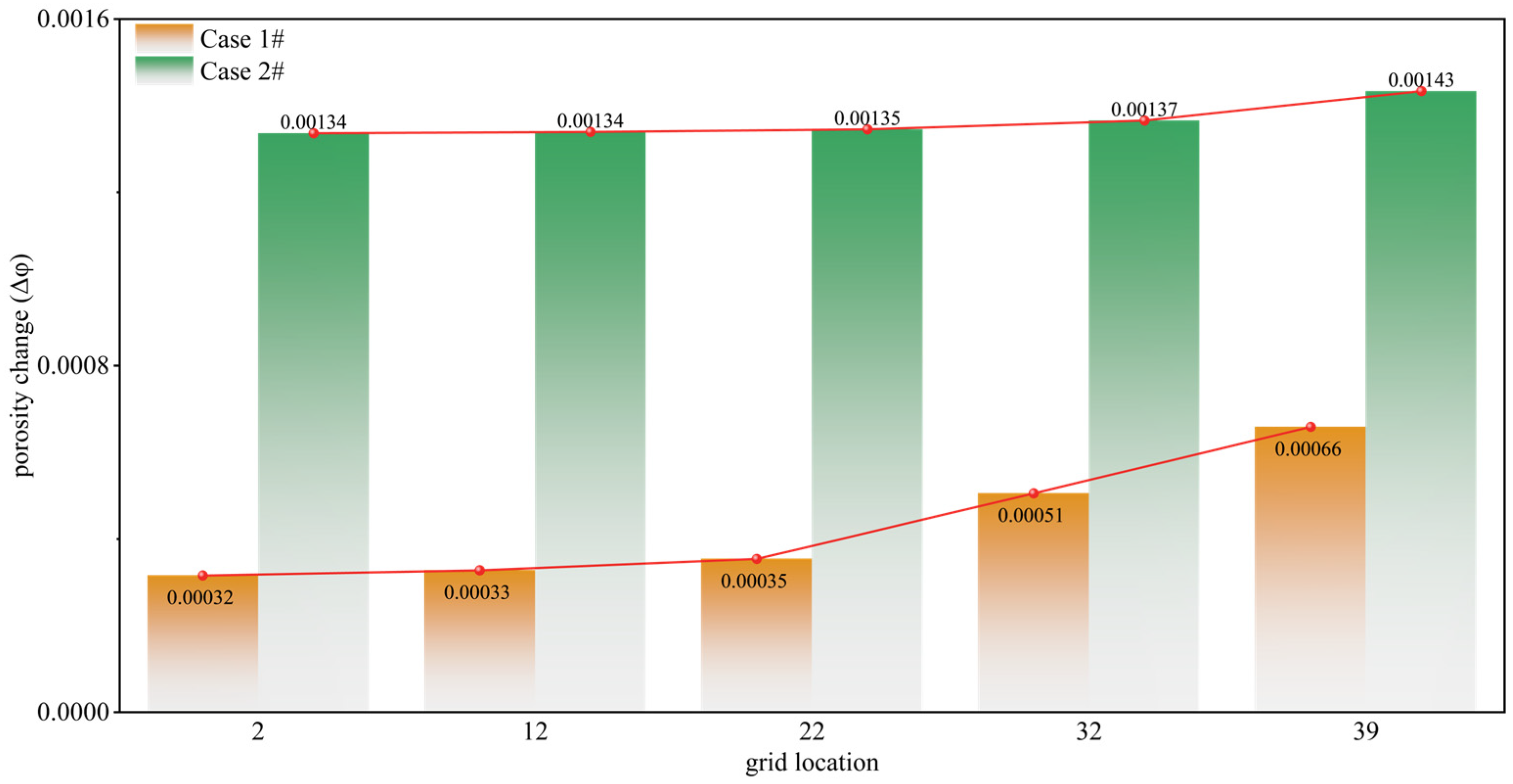

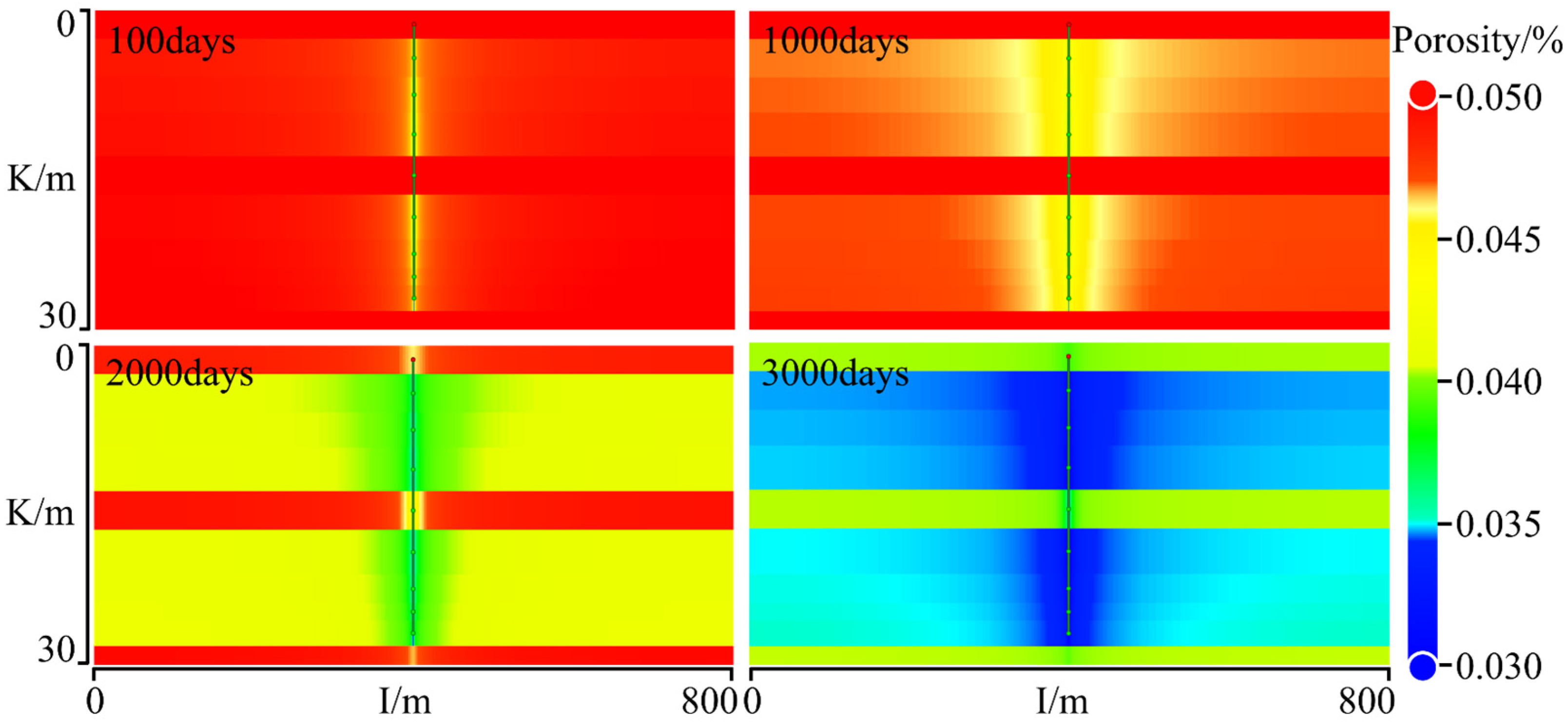

3.1. Analysis of the Geomechanical Response

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

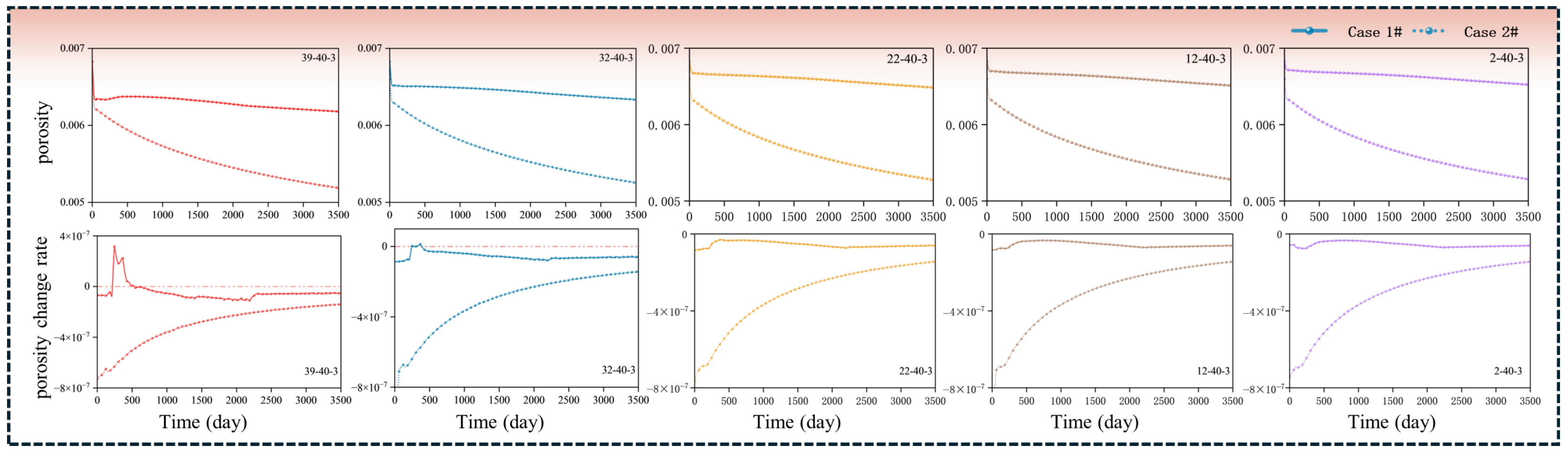

3.2.1. Reservoir Porosity

3.2.2. Natural Fracture Permeability

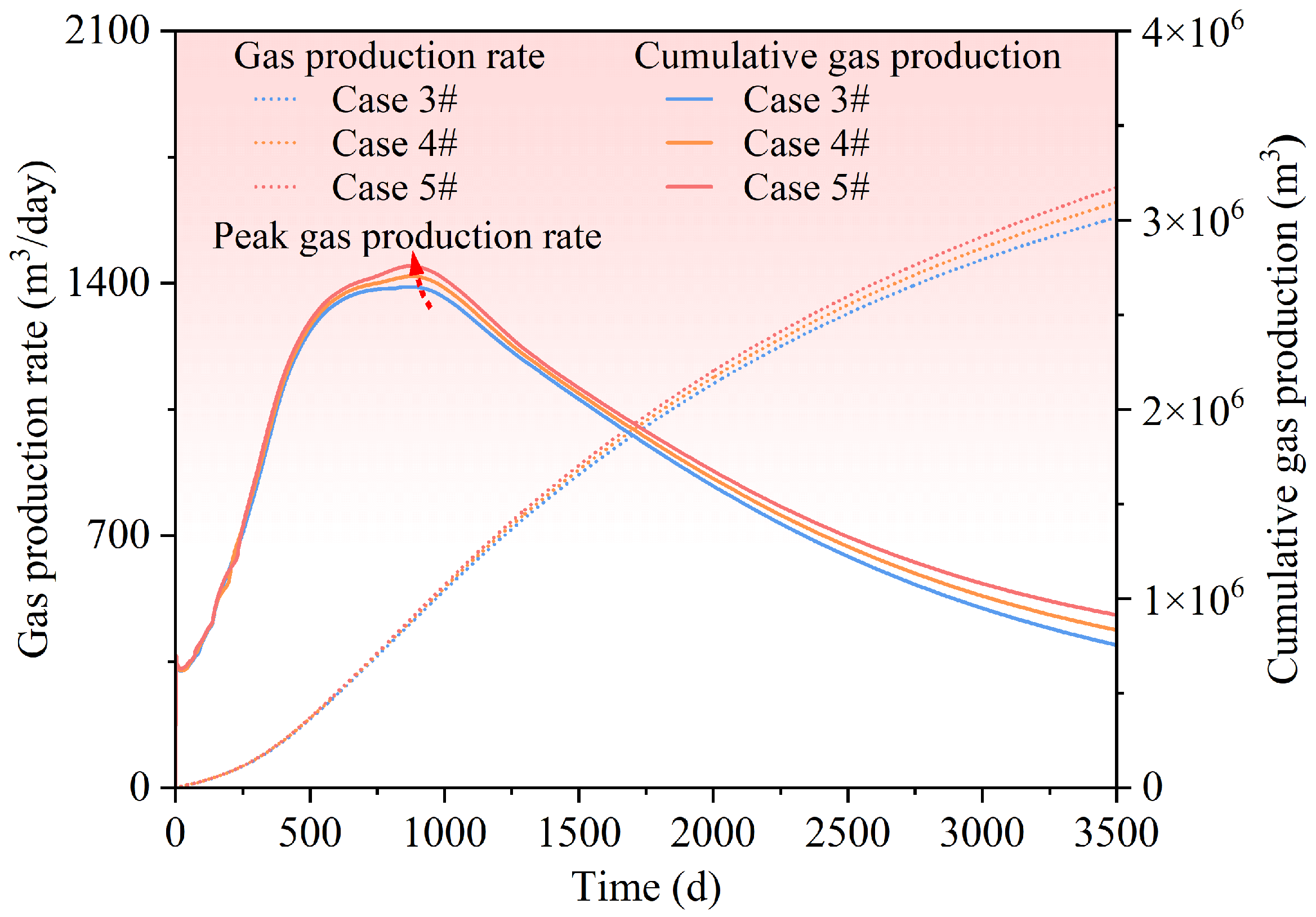

3.2.3. Stimulated Reservoir Volume (SRV)

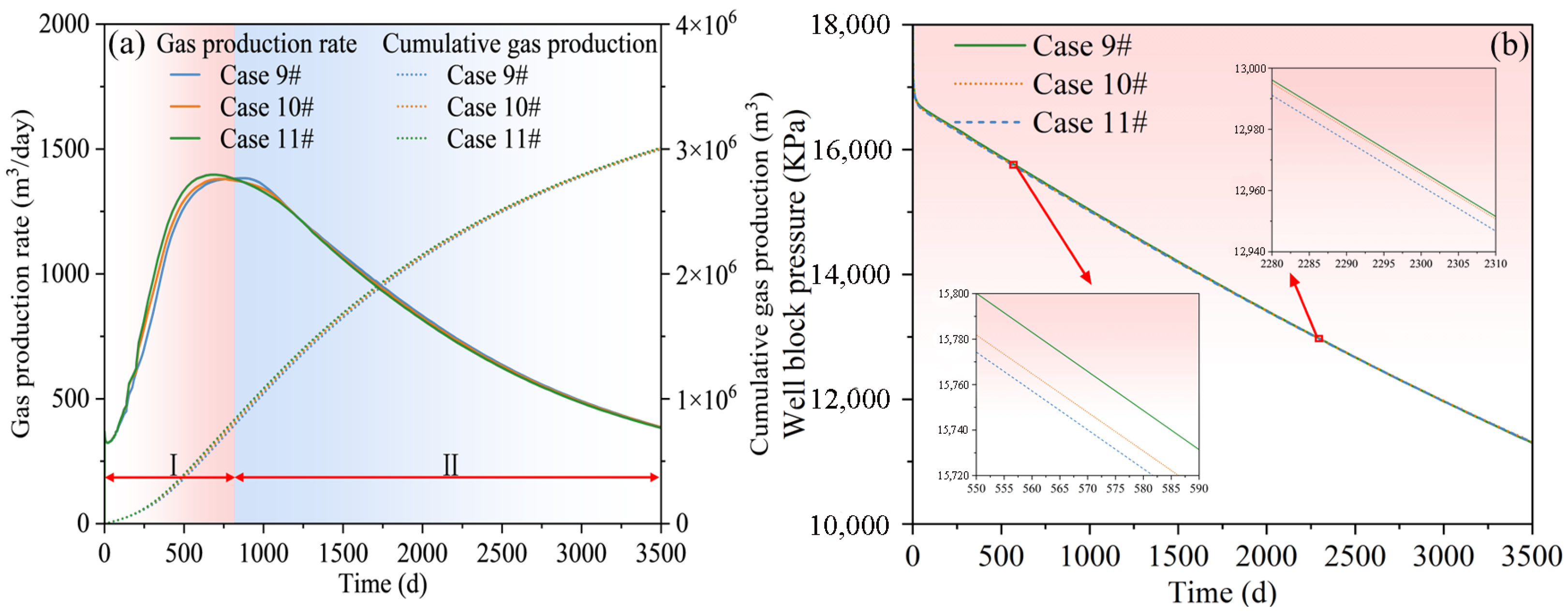

3.2.4. Hydraulic Fracture Permeability

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, B.; Nie, B.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, S.; Li, Z.; Luo, X. Enhanced coalbed methane extraction by high-strength electric detonation technology: Numerical study and field test. Fuel 2025, 396, 135340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Han, S.; Ren, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, W.; Guo, Z.; Yang, Y. Characteristics of middle-high-rank coal reservoirs and prospects for CBM exploration and development in western Guizhou, China. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2024, 11, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuhua, C.; Luo, J.; Wu, C.; Hu, X.; Yang, Y.; Wei, C. A model of evaluating dynamical process of the interlayer interference of tight gas and coalbed methane and its application. Gas Sci. Eng. 2025, 134, 205528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, B.; Guo, P.; Zhang, X. Fracture propagation characteristics driven by liquid CO2 BLEVE for coalbed methane recovery. Fuel 2025, 381, 133162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xu, J.; Shu, L.; Yan, F.; Pang, B.; Peng, S. Exploration of the induced fluid-disturbance effect in CBM co-production in a superimposed pressure system. Energy 2023, 265, 126347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Song, X.; Li, G.; Shi, Y.; Wang, G.; Ji, J.; Xu, F.; Song, Z. An integrated multi-objective optimization method to improve the performance of multilateral-well geothermal system. Renew. Energy 2021, 172, 1233–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Qin, Y.; Tang, D.; Shen, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, S. A comprehensive review of deep coalbed methane and recent developments in China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2023, 279, 104369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, S.; He, H.; He, X.; Zhao, Z.; Niu, X.; Xiong, X.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, X.; Hou, Y.; et al. Coal-rock gas: Concept, connotation and classification criteria. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Shi, Y.; Xu, F.; Song, X.; Li, G.; Wang, G.; Lv, Z. The magnitudes of multi-physics effects on geothermal reservoir characteristics during the production of enhanced geothermal system. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Vandeginste, V.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Chang, X.; Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, C.; Luo, J.; Quan, F.; et al. Control mechanism of pressure drop rate on coalbed methane productivity by using production data and physical simulation technology. Fuel 2026, 406, 137060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Mendhe, V.A.; Singh, V.P.; Shukla, P.; Murthy, S. Unveiling the petrographical, palynological, palynofacies and geochemical archives of coal and shaly coal deposits in the Mandakini–B block of Talcher Basin: An insight into the paleoecology, depositional environment, kerogen type and source rock potential. Gondwana Res. 2024, 132, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Niu, D.; Luan, Z.; Dang, H.; Pan, X.; Sun, P. Kinetic characteristics of secondary hydrocarbon generation from oil shale and coal at different maturation stages: Insights from open-system pyrolysis. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2025, 308, 104845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirico, E.; Bonal, L.; Montagnac, G.; Beck, P.; Reynard, B. New insights into the structure and formation of coals, terrestrial and extraterrestrial kerogens from resonant UV Raman spectroscopy. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2020, 282, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-J.; Huang, W.-L.; Hsu, A.; Huang, S.-Y.L. Characterization of kerogens and coals using fluorescence measured in situ at elevated temperatures. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2008, 75, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Tao, S.; Sun, B.; Tang, S.; Chen, S.; Wen, Y.; Ye, J. Genesis and accumulation mechanism of external gas in deep coal seams of the Baijiahai uplift, Junggar Basin, China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2024, 286, 104506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, S.; Feng, G.; Li, G. Research on acidizing blockage removal to enhance gas production in low-yield coalbed methane horizontal wells. Fuel 2026, 404, 136197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Huang, B.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, M.; Li, Y. Gas-phase production equation for CBM reservoirs: Interaction between hydraulic fracturing and coal orthotropic feature. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 213, 110428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Yao, Y.; Liu, D.; Qiu, Y. CO2-enhanced methane recovery in deep coalbeds: Displacement and diffusion/pressure-driven behaviors. Gas Sci. Eng. 2025, 143, 205730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, S.; Zhong, G.; Feng, P.; Chang, C.; Li, H. Characteristics of in-situ stress field of coalbed methane reservoir in the eastern margin of Ordos Basin. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2025, 301, 104715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Qin, Y.; Guo, T.; Shen, J.; Yang, Y. Supercritical methane adsorption in coal and implications for the occurrence of deep coalbed methane based on dual adsorption modes. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Deng, Z.; Hu, H.; Ding, R.; Tian, F.; Zhang, T.; Ma, Z.; Wang, D. Pore structure of deep coal of different ranks and its effect on coalbed methane adsorption. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 59, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Wang, M.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Z.; Xiu, C.; Jia, G.; Li, Q.; Lu, D. Field experiment of stress sensitivity effect in the Mabidong CBM block, southern Qinshui Basin, China. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 222, 211441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, P.; Xu, H.; Tang, D.; Zhao, T. A dynamic prediction model of reservoir pressure considering stress sensitivity and variable production. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 225, 211688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, K.; Chen, T.; Zhou, L.; Li, B. Engineering sweet spot evaluation of deep coal seam: Algorithm construction and application integrated with geological sweet spot—A case study in Ordos Basin, China. SPE J. 2025, 30, 2530–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Wang, E.; Liu, Q.; Jia, H.; Wang, D. Vibration-enhanced coalbed methane recovery: Coupled vibration-thermo-hydro-mechanical modeling. Gas Sci. Eng. 2025, 139, 205634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Song, X.; Xu, F.; Li, G.; Shi, Y.; Ji, J. Contributions of thermo-poroelastic and chemical effects to the production of enhanced geothermal system based on thermo-hydro-mechanical-chemical modeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Lu, H.; Huang, L.; Luo, P. A molecular dynamics study of methane/water diffusion and water-blocking effects in coalbed methane. Fuel 2025, 386, 134234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Hu, S.; Zhang, X.; Feng, G.; Sun, X. Numerical investigation of seepage characteristics of propped fracture in coalbed methane reservoirs. Gas Sci. Eng. 2023, 110, 204863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.R. Material-balance techniques for coal-seam and Devonian shale gas reservoirs with limited water influx. SPE Reserv. Eng. 1993, 8, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaei-Farouji, M.; Misch, D.; Sachsenhofer, R.F. A review of influencing factors and study methods of carbon capture and storage (CCS) potential in coals. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2023, 277, 104351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Gong, B.; Wu, H.; Huang, H.; Zhao, H. Intelligent coalbed methane drainage optimization: A deep reinforcement learning-driven life-cycle strategy. Energy AI 2025, 22, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Qin, Y.; Yang, D.; Wang, G.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, F. Experimental investigation of gas diffusion kinetics and pore-structure characteristics during coalbed methane desorption within a coal seam. Gas Sci. Eng. 2024, 121, 205173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, L.D. A new interpretation of the response of coal permeability to changes in pore pressure, stress and matrix shrinkage. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2016, 162, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Gan, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Cao, P. Research and application of seismic exploration technology in coalbed methane exploration in Hujiertai block, Yili. Coal Technol. 2025, 44, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, L.D. Coupled flow and geomechanical processes during gas production from coal seams. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2009, 79, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, P.-L.; Nguyen, X.-X.; Dong, J.-J. A novel method to estimate the Stress-Dependent Kozeny-Carman constant of Low-Permeability, clastic sedimentary rocks. J. Hydrol. 2023, 621, 129595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Liang, Y.; Elsworth, D.; Yao, Q.; Fu, X.; Kang, J.; Hao, Y.; Wang, M. Permeability evolution and production characteristics of inclined coalbed methane reservoirs on the southern margin of the Junggar Basin, Xinjiang, China. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2023, 171, 105581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Song, X.; Ji, J.; Wu, X.; Li, G.; Xu, F.; Shi, Y.; Wang, G. Evolution of fracture aperture and thermal productivity influenced by chemical reaction in enhanced geothermal system. Renew. Energy 2022, 186, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Huang, W.; Chen, X.; Hu, W.; et al. Numerical modeling of deep coalbed methane accumulation in the central-eastern Ordos Basin, China. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2024, 11, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Pan, Z.; Durucan, S. Analytical models for coal permeability changes during coalbed methane recovery: Model comparison and performance evaluation. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2014, 136, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Han, D.; Xu, H.; Chu, X.; Qin, Y. Modeling of gas migration in a dual-porosity coal seam around a borehole: The effects of three types of driving forces in coal matrix. Energy 2023, 264, 126181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Huang, W.; Cui, Z.; Liu, L.; Duan, L.; Zhao, Y. Play fairway mapping and strategies for efficient production of low-rank coalbed methane in the Surat block, Australia. Oil Gas Geol. 2025, 46, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, Z.; Wang, E.; Feng, X.; Kong, X.; Wang, D. Synchronous inversion of coal seam gas pressure and permeability based on a dual porosity/dual permeability model and surrogate optimization algorithm. Nat. Resour. Res. 2023, 32, 2115–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Kang, T.; Kang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Zhu, W.; Guo, J.; Zhang, B. Investigation of limonene leaching effects on methane adsorption–desorption behaviors in various rank coals: Insights from surface chemical composition and chemical structure analyses. Fuel 2025, 379, 133047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Lun, Z.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, D. Influences of controlled microwave field irradiation on physicochemical property and methane adsorption and desorption capability of coals: Implications for coalbed methane (CBM) production. Fuel 2021, 301, 121022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, Y.; Wu, C.; Yi, T.; Li, Y.; Tang, J.; Chen, J. Optimization methods of production layer combination for coalbed methane development in multi-coal seams. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2018, 45, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 35210.2-2020; Determination Methods of Methane Isothermal Adsorption of Shale—Part 2: Gravimetric Method. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Hu, K.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Thaika, M.A. A developed dual-site Langmuir model to represent the high-pressure methane adsorption and thermodynamic parameters in shale. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2023, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, K.; Hu, Y.; Nie, Z.; Shi, Y. Coalbed methane extraction: Characteristics of damage-seepage evolution and dynamic response of methane transport in non-homogeneous coal seams under cavitation. Gas Sci. Eng. 2025, 142, 205689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Meng, Z.; Li, G. Diffusion characteristics of methane in various rank coals and the control mechanism. Fuel 2021, 283, 118959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, D.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Ren, K. Study on in situ stress testing method based on Kaiser effect of acoustic emission and COMSOL simulation. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 17, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, J.X.; Zhu, Y.; Rudolph, V.; Chen, Z. Impact of gas adsorption on coal relative permeability: A laboratory study. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2025, 194, 106191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Layer No. | Lithology | Thickness (m) | Porosity (%) | Permeability (mD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix | Fracture | Matrix | Fracture | |||

| 1 | Sandstone | 2.7 | 7.19 | N/A | 36 | N/A |

| 2 | Coal | 3.6 | 8.24 | 5 | PermI = PermJ = 0.56 PermK = 0.056 | PermI = PermJ = 20 PermK = 2 |

| 3 | 3.3 | |||||

| 4 | 4.1 | |||||

| 5 | Sandstone | 3.6 | 7.19 | N/A | 36 | N/A |

| 6 | Coal | 4.2 | 8.24 | 5 | PermI = PermJ = 0.48 PermK = 0.048 | PermI = PermJ = 18 PermK = 1.8 |

| 7 | 2.7 | |||||

| 8 | 1.6 | |||||

| 9 | 2.4 | |||||

| 10 | Sandstone | 1.8 | 7.19 | N/A | 36 | N/A |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Gas Critical Adsorption Pressure (kPa) | 2570 |

| Gas Maximum Adsorbed Volume (m3/kg) | 0.01434 |

| Gas Adsorption Constant (1/kPa) | 0.000389105 |

| Coal Density (kg/m3) | 1380 |

| Mechanical Parameter | Value | Mechanical Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young’s Modulus (GPa) | 5.591 | Horizontal Stress Gradient (KPa/m) | 15.1 |

| Poisson’s Ratio | 0.473 | Vertical Stress Gradient (KPa/m) | 19.4 |

| Biot’s Coefficient | 0.994 | Friction Angle (°) | 40.0 |

| Maximum Horizontal Stress (MPa) | 30.190 | Matrix Shrinkage Model | Palmer-Mansoori |

| Minimum Horizontal Stress (MPa) | 22.790 | Yield Criterion | Mohr-Coulomb |

| Vertical Stress (MPa) | 38.204 |

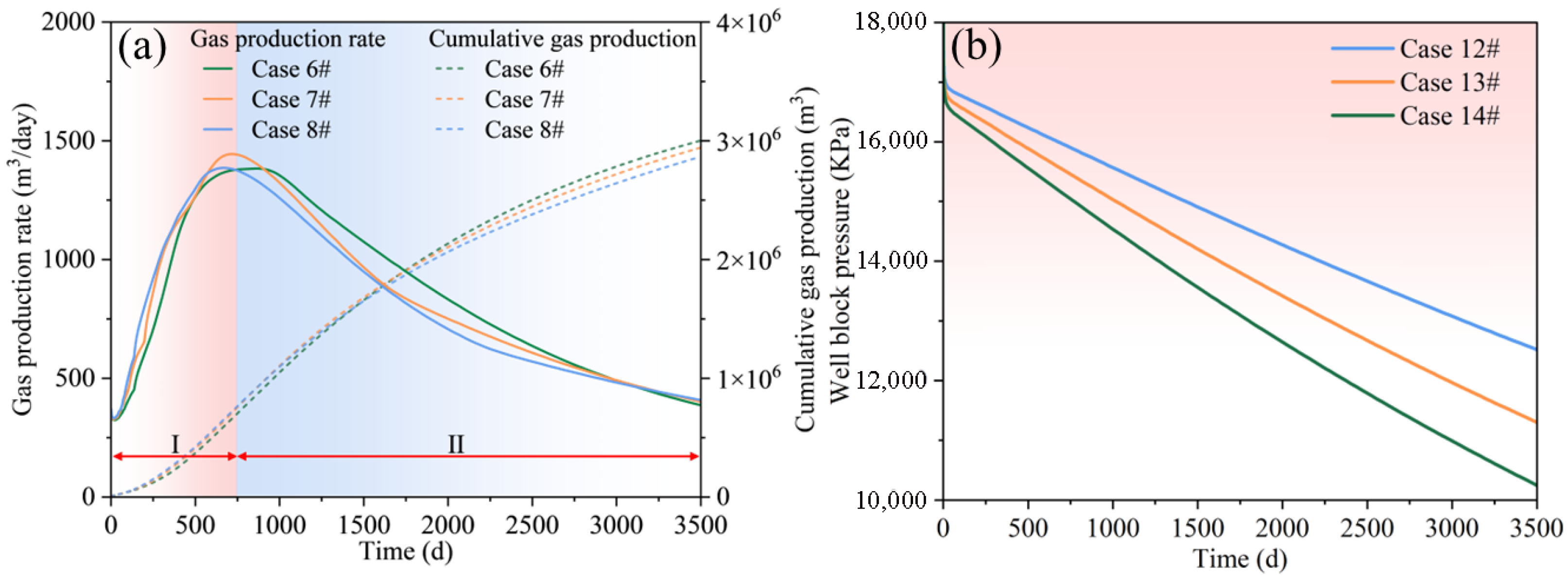

| Case | Geomechanics | Porosity (%) | Natural Fracture Perm (mD) | SRV (m3) | Hydraulic Fracture Perm (mD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1# | Coupled | 8.24 | 20 | 9.466 × 105 | 2000 |

| 2# | Uncoupled | ||||

| 3# | Coupled | 10.00 | 20 | 9.466 × 105 | 2000 |

| 4# | 15.00 | ||||

| 5# | 20.00 | ||||

| 6# | 8.24 | 20 | 9.466 × 105 | 2000 | |

| 7# | 30 | ||||

| 8# | 40 | ||||

| 9# | 8.24 | 20 | 1.000 × 106 | 2000 | |

| 10# | 2.000 × 106 | ||||

| 11# | 3.000 × 106 | ||||

| 12# | 8.24 | 20 | 9.466 × 105 | 1500 | |

| 13# | 2000 | ||||

| 14# | 2500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mu, Z.; Wang, R.; Zhang, P.; Zeng, C.; Han, M.; Wei, Q.; Yin, P.; Wang, H. Productivity Simulation of Multilayer Commingled Production in Deep Coalbed Methane Reservoirs: A Coupled Stress-Desorption-Flow Model. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010041

Mu Z, Wang R, Zhang P, Zeng C, Han M, Wei Q, Yin P, Wang H. Productivity Simulation of Multilayer Commingled Production in Deep Coalbed Methane Reservoirs: A Coupled Stress-Desorption-Flow Model. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010041

Chicago/Turabian StyleMu, Zongjie, Rui Wang, Panpan Zhang, Changhui Zeng, Mingchen Han, Qilong Wei, Pengbo Yin, and Hu Wang. 2026. "Productivity Simulation of Multilayer Commingled Production in Deep Coalbed Methane Reservoirs: A Coupled Stress-Desorption-Flow Model" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010041

APA StyleMu, Z., Wang, R., Zhang, P., Zeng, C., Han, M., Wei, Q., Yin, P., & Wang, H. (2026). Productivity Simulation of Multilayer Commingled Production in Deep Coalbed Methane Reservoirs: A Coupled Stress-Desorption-Flow Model. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010041