A Review of Numerical Simulation Tools for Coupling Earth’s Interior and Lithospheric Stress Fields

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fundamental Equations

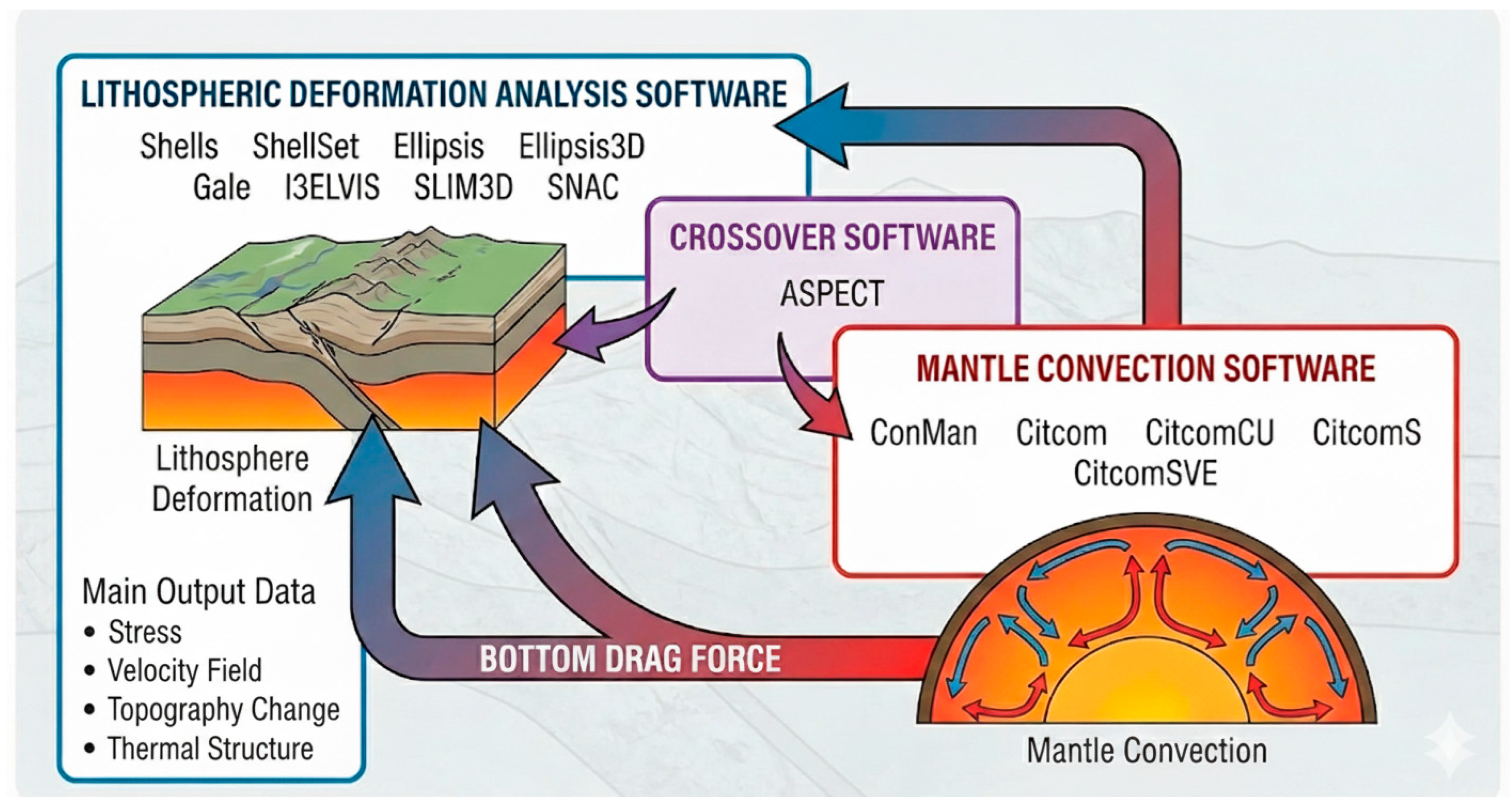

3. Numerical Simulation Software for Global Stress Field

3.1. Lithospheric Deformation Analysis Software

3.1.1. Shells Software Series

3.1.2. Ellipsis Software Series

3.1.3. Gale

3.1.4. I3ELVIS

3.1.5. SLIM3D

3.1.6. SNAC

3.2. Mantle Convection Analysis Software

3.2.1. ConMan

3.2.2. Citcom Software Series

3.2.3. ASPECT

4. Application in the Analysis of Global Stress Field

4.1. Applications of Shells Software Series

4.2. Applications of Ellipsis Software Series

4.3. Applications of Gale

4.4. Applications of I3ELVIS

4.5. Applications of SNAC

4.6. Applications of ASPECT

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hager, B.H.; O’Connell, R.J. A simple global model of plate dynamics and mantle convection. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1981, 86, 4843–4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreemer, C.; Holt, W.E.; Haines, A.J. An integrated global model of present-day plate motions and plate boundary deformation. Geophys. J. Int. 2003, 154, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karato, S.-I.; Wu, P. Rheology of the upper mantle: A synthesis. Science 1993, 260, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Huang, Y.R.; Gao, A.J. The tectonic stress field of chinese continent deduced from a great number of earthquakes. Chin. J. Geophys. 1989, 32, 636–647. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Q.M. Long-range effects of mid-ocean ridge dynamics on earthquakes, magmatic activities, and mineralization events in plate subduction zones. Earth Sci. Front. 2024, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.P.; Hui, P.; Wang, B.; Sun, S.S.; Yao, H.J.; Liu, J.L.; Zang, R.T.; Li, Y.C.; Luo, Q.X. Transform faults and transfer faults: Plate boundary and intra-continental tectonic dynamics transition. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2025, 68, 3867–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.G.; He, X.H.; Xu, S.F.; Zheng, W.J.; Liu, T.; Liu, Z.L. Earthquake relocation and regional stress field around the eastern Himalayan syntaxis. Rev. Geophys. Planet. Phys. 2023, 54, 667–683. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, X.Y. A research on the conversion of gravity field into regional tectonic stress field. Chin. J. Geophys. 1994, 37, 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F.X.; Xiao, Y.; Miao, Y.W. Inversion of tectonic stress field in Sichuan-Yunnan area using EGM2008 model and ground gravity observation. J. Geod. Geodyn. 2015, 35, 445–448. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, J.L.; Hui, L.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Li, Z.Y. Research on horizontal tectonic stress field based on EGM2008 in western Sichuan. J. Geod. Geodyn. 2019, 39, 307–312. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, F.R.; Cui, X.F.; Zhao, J.T. Analysis of global tectonic stress field. Earth Sci. Front. 2003, 10, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, F.R.; Cui, X.F.; Zhao, J.T.; Chen, Q.; Li, H. Regional division of the recent tectonic stress field in China and adjacent area. Chin. J. Geophys. 2004, 47, 654–662. [Google Scholar]

- Zoback, M.L.; Zoback, M.D. Tectonic stress field of the continental united states. Geol. Soc. Am. Mem. 1989, 172, 523–540. [Google Scholar]

- Zoback, M.L.; Zoback, M.D.; Adams, J.; Assumpção, M.; Bell, S.; Bergman, E.A.; Blümling, P.; Brereton, N.R.; Denham, D.; Ding, J.; et al. Global patterns of tectonic stress. Nature 1989, 341, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gripp, A.E.; Gordon, R.G. Current plate velocities relative to the hotspots incorporating the NUVEL-1 global plate motion model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1990, 17, 1109–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoback, M.L. First-and second-order patterns of stress in the lithosphere: The World Stress Map Project. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1992, 97, 11703–11728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Y.; Wei, D.P.; Chen, Q.F.; Chen, H. An analysis on short-wave components of the global stress field. Acta Seism. Sin. 2003, 25, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Y.; Wei, D.P. Global plate motions and the influence on the stress fields near the plate boundary. J. Grad. Sch. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2004, 21, 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; MUuller, R.D. Three-dimensional finite-element modelling of the tectonic stress field in continental Australia. Geol. Soc. Am. Mem. 2003, 372, 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lithgow-Bertelloni, C.; Guynn, J.H. Origin of the lithospheric stress field. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2004, 109, B01408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Holt, W.E. Plate motions and stresses from global dynamic models. Science 2012, 335, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundall, P.A. Formulation of a three-dimensional distinct element model—Part I. A scheme to detect and represent contacts in a system composed of many polyhedral blocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1988, 25, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresi, L.; Zhong, S.; Gurnis, M. The accuracy of finite element solutions of Stokes’s flow with strongly varying viscosity. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 1996, 97, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.; Choi, E.; Thoutireddy, P.; Gurnis, M.; Aivazis, M. GeoFramework: Coupling multiple models of mantle convection within a computational framework. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2006, 7, Q06001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, J.; Sacek, V. Benchmark comparison study for mantle thermal convection using the CitcomCU numerical code. In Proceedings of the 15th International Congress of the Brazilian Geophysical Society and EXPOGEF, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 31 July –3 August 2017; pp. 1630–1635. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, S.; Kang, K.; A, G.; Qin, C. CitcomSVE: A three-dimensional finite element software package for modeling planetary mantle’s viscoelastic deformation in response to surface and tidal loads. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2022, 23, e2022GC010359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronbichler, M.; Heister, T.; Bangerth, W. High accuracy mantle convection simulation through modern numerical methods. Geophys. J. Int. 2012, 191, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, W.; Hodkinson, L. Gale: Large scale tectonics modelling with free software. In Proceedings of the AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, San Francisco, CA, USA, 10–14 December 2007; p. 343. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.; Bird, P. SHELLS: A thin-shell program for modeling neotectonics of regional or global lithosphere with faults. J. Geophys. Res. 1995, 100, 22129–22131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J.B.; Bird, P.; Carafa, M.M.C. ShellSet v1.1.0 parallel dynamic neotectonic modelling: A case study using Earth5-049. Geosci. Model Dev. 2024, 17, 6153–6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.-S.; Lavier, L.; Gurnis, M. Thermomechanics of mid-ocean ridge segmentation. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2008, 171, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ye, Z.R. Effects of mantle flow on generation and distribution of global lithospheric stress field. Chin. J. Geol. 2005, 48, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresi, L.N.; Lenardic, A. Three-dimensional numerical simulations of crustal deformation and subcontinental mantle convection. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1997, 150, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerya, T.V.; Yuen, D.A. Robust characteristics method for modelling multiphase visco-elasto-plastic thermo-mechanical problems. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2007, 163, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukao, Y.; Obayashi, M.; Inoue, H.; Nenbai, M. Subducting slabs stagnant in the mantle transition zone. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1992, 97, 4809–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, W.R. Modes of continental lithospheric extension. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1991, 96, 20161–20178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navier, H. Mémoire sur les lois du mouvement des fluides. Mémoires De L’académie R. Des Sci. 1827, 6, 389–440. [Google Scholar]

- Helffrich, G.R.; Wood, B.J. The Earth’s mantle. Nature 2001, 412, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moresi, L.; Dufour, F.; Mühlhaus, H.B. A Lagrangian integration point finite element method for large deformation modeling of viscoelastic geomaterials. J. Comput. Phys. 2003, 184, 476–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, C.; Moresi, L.; Müller, D.; Albert, R.; Dufour, F. Ellipsis 3D: A particle-in-cell finite-element hybrid code for modelling mantle convection and lithospheric deformation. Comput. Geosci. 2006, 32, 1769–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.A.; Sobolev, S.V. SLIM3D: A tool for three-dimensional thermomechanical modeling of lithospheric deformation with elasto-visco-plastic rheology. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2008, 171, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.D.; Raefsky, A.; Hager, B.H. Conman: Vectorizing a finite element code for incompressible two-dimensional convection in the Earth’s mantle. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 1990, 59, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, P.; Kong, X. Computer simulations of California tectonics confirm very low strength of major faults. GSA Bull. 1994, 106, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, P. New finite element techniques for modeling deformation histories of continents with stratified temperature-dependent rheology. J. Geophys. Res. 1989, 94, 3967–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tackley, P.J. Self-consistent generation of tectonic plates in three-dimensional mantle convection. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1998, 157, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresi, L.N.; Solomatov, V.S. Numerical investigation of 2D convection with extremely large viscosity variations. Phys. Fluids 1995, 7, 2154–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresi, L.; Gurnis, M. Constraints on the lateral strength of slabs from three-dimensional dynamic flow models. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1996, 138, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; McNamara, A.; Tan, E.; Moresi, L.; Gurnis, M. A benchmark study on mantle convection in a 3D spherical shell using CitcomS. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2008, 9, Q10017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Zuber, M.T.; Moresi, L.; Gurnis, M. Role of temperature-dependent viscosity and surface plates in spherical shell models of mantle convection. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2000, 105, 11063–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Zhong, S.; Geruo, A. CitcomSVE-3.0: A three-dimensional finite-element software package for modeling load-induced deformation and glacial isostatic adjustment for an earth with a viscoelastic and compressible mantle. Geosci. Model Dev. 2025, 18, 1445–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glerum, A.; Thieulot, C.; Fraters, M.; Blom, C.; Spakman, W. Nonlinear viscoplasticity in ASPECT: Benchmarking and applications to subduction. Solid Earth 2018, 9, 267–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, P. Testing hypotheses on plate-driving mechanisms with global lithosphere models including topography, thermal structure, and faults. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1998, 103, 10115–10129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, P.; Liu, Z.; Rucker, W.K. Stresses that drive the plates from below: Definitions, computational path, model optimization, and error analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2008, 113, B11406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunini, L.; Jiménez-Munt, I.; Fernandez, M.; Vergés, J.; Bird, P. Neotectonic deformation in central Eurasia: A geodynamic model approach. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2017, 122, 9461–9484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xiong, X.S.; Li, Q.S.; Lu, Z.W.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wu, G.W.; Wang, S. Deep seismic exploration and lithospheric structure in southeastern margin of tibetan plateau. East China Geol. 2025, 46, 16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney, D.L.; Teyssier, C.; Rey, P.F. The consequences of crustal melting in continental subduction. Lithosphere 2009, 1, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Lee, C. Effects of temporal plume–slab interaction on the partial melting of the subducted oceanic crust. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 113, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, C.; Kim, S.-S. Tectonics and volcanism in East Asia: Insights from geophysical observations. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 113, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Leng, W.; Chen, L. Continental tip with thinned lithosphere and thickened crust is a favorable location for subduction initiation. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2023, 128, e2023JB027067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tackley, P.J. Self-consistent generation of tectonic plates in time-dependent, three-dimensional mantle convection simulations. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2000, 1, 2000GC000036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heck, H.J.; Tackley, P.J. Planforms of self-consistently generated plates in 3D spherical geometry. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L19312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Forsyth, D.W. Rayleigh wave phase velocities, small-scale convection, and azimuthal anisotropy beneath southern California. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2006, 111, B07306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, N.P.; Bennett, R.A.; Spinler, J.C.; Humphreys, E.D. Small-scale upper mantle convection and crustal dynamics in southern California. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2008, 9, Q08006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A, G.; Wahr, J.; Zhong, S. Computations of the viscoelastic response of a 3D compressible Earth to surface loading: An application to glacial isostatic adjustment in Antarctica and Canada. Geophys. J. Int. 2012, 192, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. The influence of uncertain mantle density and viscosity structures on the calculations of deep mantle flow and lateral motion of plumes. Geophys. J. Int. 2023, 233, 1916–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assuncao, J.; Sacek, V. Heat Transfer Regimes in Mantle Dynamics Using the CitcomCU Software. In Proceedings of the 15th International Congress of the Brazilian Geophysical Society, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 31 July–3 August 2017; pp. 1636–1639. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E.-S.; Gurnis, M. Thermally induced brittle deformation in oceanic lithosphere and the spacing of fracture zones. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2008, 269, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negredo, A.; Clemente, C.; Carminati, E.; Jiménez-Munt, I.; Verges, J.; Fullea, J.; Torné, M. Thermo-mechanical modelling of subducting plate delamination in the northern Apennines. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly 2021, Virtual, 19–30 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Faucher, A.; Gueydan, F.; Van Hunen, J. Strike-slip faulting in extending upper plates: Insight from the aegean. EGUsphere 2024, 569, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, K.; McKenzie, D.; Ho, T. A lithosphere–asthenosphere boundary—A global model derived from multimode surface-wave tomography and petrology. In Lithospheric Discontinuities; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- van Zelst, I.; Crameri, F.; Pusok, A.E.; Glerum, A.; Dannberg, J.; Thieulot, C. 101 geodynamic modelling: How to design, interpret, and communicate numerical studies of the solid Earth. Solid Earth 2022, 13, 583–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perchuk, A.L.; Gerya, T.V.; Zakharov, V.S.; Griffin, W.L. Depletion of the upper mantle by convergent tectonics in the Early Earth. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerya, T.V.; Yuen, D.A. Characteristics-based marker-in-cell method with conservative finite-differences schemes for modeling geological flows with strongly variable transport properties. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2003, 140, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.D.; Cannon, J.; Qin, X.; Watson, R.J.; Gurnis, M.; Williams, S.; Pfaffelmoser, T.; Seton, M.; Russell, S.H.J.; Zahirovic, S. GPlates: Building a Virtual Earth Tharough Deep Time. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2018, 19, 2243–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crameri, F. Geodynamic diagnostics, scientific visualisation and StagLab 3.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 2018, 11, 2541–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Software | Developer/Institution | License Type | Community Support and Maintenance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shells/ShellSet | P. Bird (UCLA)/J. May | Open Source (GPL/Academic) | Academic maintenance; support via documentation and user groups. |

| Ellipsis/Ellipsis3D | CIG/L. Moresi | Open Source (GPL) | Legacy support; succeeded by Underworld, community support via CIG. |

| Gale | CIG/VPAC/Monash Univ. | Open Source (GPL) | Supported by CIG (Computational Infrastructure for Geodynamics); extensive manuals and forums. |

| I3ELVIS | T. Gerya (ETH Zurich) | Academic/Proprietary | Code often shared upon collaboration/request; support limited to research group. |

| SNAC | Caltech/CIG | Open Source | CIG hosted; community-driven updates. |

| Citcom Series | CIG (originally Caltech) | Open Source (GPL) | Strong CIG support; regular benchmarks and active user forums. |

| SLIM3D | GFZ Potsdam | Academic | Internal maintenance; specialized use cases. |

| Software | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shells | Based on the thin shell theory, the lithosphere is modeled as a thin elastic/plastic shell. | Low computational cost; the simulation of plate flexure and large-scale horizontal movements is intuitive and easy to understand. | Simplifies 3D problems to 2D horizontal equilibrium, ignoring vertical fine-scale structures and complex deep processes. |

| Shellset | Extends thin shell theory by integrating layered shell elements with viscoelastic/anisotropic rheological properties to adapt to layered lithospheric structures. | Balances accuracy and efficiency; supports time-dependent processes (e.g., viscoelasticity) for neotectonic simulation; uses Eulerian mesh and particle tracking to record material deformation history. | Static refinement setup has a steep learning curve; thin shell approximation limits 3D simulations; small geological material elements fail to transmit key information (e.g., heat); resolution is mesh-constrained with high storage demands; lacks dynamic adaptive mesh refinement capability, leading to poor flexibility in mesh adjustment during simulation and poor compatibility with other modules. |

| Ellipsis3D | Full 3D thermo-mechanical finite element method, coupling heat conduction and deformation to simulate lithosphere–mantle interactions. | Captures 3D volumetric processes; achieves realistic rheological responses via thermo-mechanical coupling. | Extremely high computational requirements (large memory/CPU consumption); time-consuming transient global simulations; no adaptive mesh refinement support. |

| Gale | Three-dimensional spectral element method with high-order polynomial spatial discretization, simulating wave propagation and quasi-static deformation. | High accuracy; strong versatility; simulates dynamic and quasi-static processes simultaneously. | Complex spectral element implementation; high-order basis functions require large memory for global models. |

| I3ELVIS | Three-dimensional finite element difference method with adaptive mesh refinement, focusing on lithosphere–asthenosphere interactions and rifting processes. | High flexibility in simulating strong rheological transition zones; high efficiency in resource utilization, avoiding excessive resolution in stable zones. | Finite difference stencils poorly handle complex curvature regions; high computational resource requirements; large number of markers to process. |

| SLIM3D | Three-dimensional spherical finite elements, incorporating Earth’s curvature and spherical harmonic function properties to simulate global lithospheric deformation. | Accurate global deformation simulation via spherical geometry; adapts to large-scale tectonic force simulation. | Complex spherical mesh generation; high computational cost (comparable to full 3D finite elements); closed-loop model of mantle heat flux, lithospheric melting, and buoyancy-driven flow. |

| SNAC | Explicit Lagrangian finite difference method, simulating lithospheric elasto-viscoplastic dynamic deformation. | Strong capability in simulating highly nonlinear deformation; supports strain weakening and elasto-viscoplastic rheology; accurately captures fault localization. | Explicit time integration limited by stability conditions (small time steps); extremely time-consuming for long-term global simulations; lower efficiency than implicit finite element method for slow quasi-static deformation. |

| Software | Numerical Methods and Core Equations | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| ConMan | Two-dimensional finite element method; solves mantle convection equations with infinite Prandtl number. | Open-source and lightweight, easy to use, suitable for studying fundamental mantle convection mechanisms (e.g., laminar flow, and plumes). | Two-dimensional only, unable to simulate global 3D convection; low computational efficiency, unsuitable for large-scale problems. |

| Citcom | Three-dimensional finite element method; PETSc-based parallel solver with MPI + OpenMP hybrid parallelism. | Modular design; supports multi-physics coupling; suitable for regional mantle convection. | Simplifying assumptions are required for global-scale simulations; computational cost for complex rheology is high. |

| CitcomCU | Three-dimensional finite element method; PETSc-based DMPlex adaptive mesh; supports spherical geometry. | Suitable for global mantle convection–plate motion coupled simulations; supports complex boundary conditions; strong GPS/seismic data assimilation capability. | Requires simplifying assumptions for global simulations; high computational cost for complex rheology. |

| CitcomS | Three-dimensional spherical finite element method; global mantle convection model based on spherical harmonic function expansion. | High precision; supports complex physical processes and temperature-dependent viscosity; multi-scale coupling via Pyre framework. | High computational cost for high-resolution simulations (large number of time steps); only supports spherical geometry, poor regional problem adaptability. |

| CitcomSVE | CitcomS extension incorporates the Sub-Viscosity Envelope (SVE) model. | Realistically simulates mantle flow layering; supports fine-scale mantle plume–lithosphere interaction simulation. | SVE parameterization requires specialized geological knowledge and has a strong dependence on initial models. |

| ASPECT | Spectral Element Method with Adaptive Mesh Refinement (AMR); solves the complete Navier–Stokes equations with full inertia terms; supports complex rheologies including power law, viscoelasticity, and partial melting. | Focuses on high-gradient regions via AMR (reduces computational cost while ensuring accuracy); uses block triangular preconditioning and Algebraic Multi-Grid (AMG) to solve Stokes equation saddle-point problems; supports large-scale simulations (hundreds of millions of unknowns); 2D/3D compatible, modular design facilitates new physical process integration. | High-resolution simulations demand supercomputing time on the order of months, leading to high computational costs; memory requirements are stringent (109 meshes require more than 1 TB of memory). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, D.; Jiang, C.; Lan, X.; Tian, J. A Review of Numerical Simulation Tools for Coupling Earth’s Interior and Lithospheric Stress Fields. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010039

Zhang D, Jiang C, Lan X, Tian J. A Review of Numerical Simulation Tools for Coupling Earth’s Interior and Lithospheric Stress Fields. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Danhua, Cheng Jiang, Xiaowen Lan, and Jiayong Tian. 2026. "A Review of Numerical Simulation Tools for Coupling Earth’s Interior and Lithospheric Stress Fields" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010039

APA StyleZhang, D., Jiang, C., Lan, X., & Tian, J. (2026). A Review of Numerical Simulation Tools for Coupling Earth’s Interior and Lithospheric Stress Fields. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010039