A Novel Stability Criterion Based on the Swing Projection Polygon for Gait Rehabilitation Exoskeletons

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Human Motion Capture Data (HMCD)-Based Planning: This approach leverages motion data from healthy subjects to generate reference trajectories for patients. Techniques such as Complementary Limb Motion Estimation (CLME) and personalized gait modeling using neural networks have been developed to accommodate individual variability [6,7].

- (2)

- Gait planning based on model and geometric constraints analyzes the forward and inverse kinematic solutions of a robot based on hip and ankle joint motion parameters to generate periodic gait patterns for exoskeletons [8]. This method was pioneered by Kajita et al. in 2003 [9]. Their approach maintained a constant height for the centroid of mass (COM) and incorporated predictive optimal control to achieve precise gait planning. Subsequent research has built upon this foundation through the integration of zero-moment point (ZMP) stability theory. This evolution has led to innovations such as the virtual ZMP plane method, which provides a theoretical basis for simulation and analysis [10].

- (3)

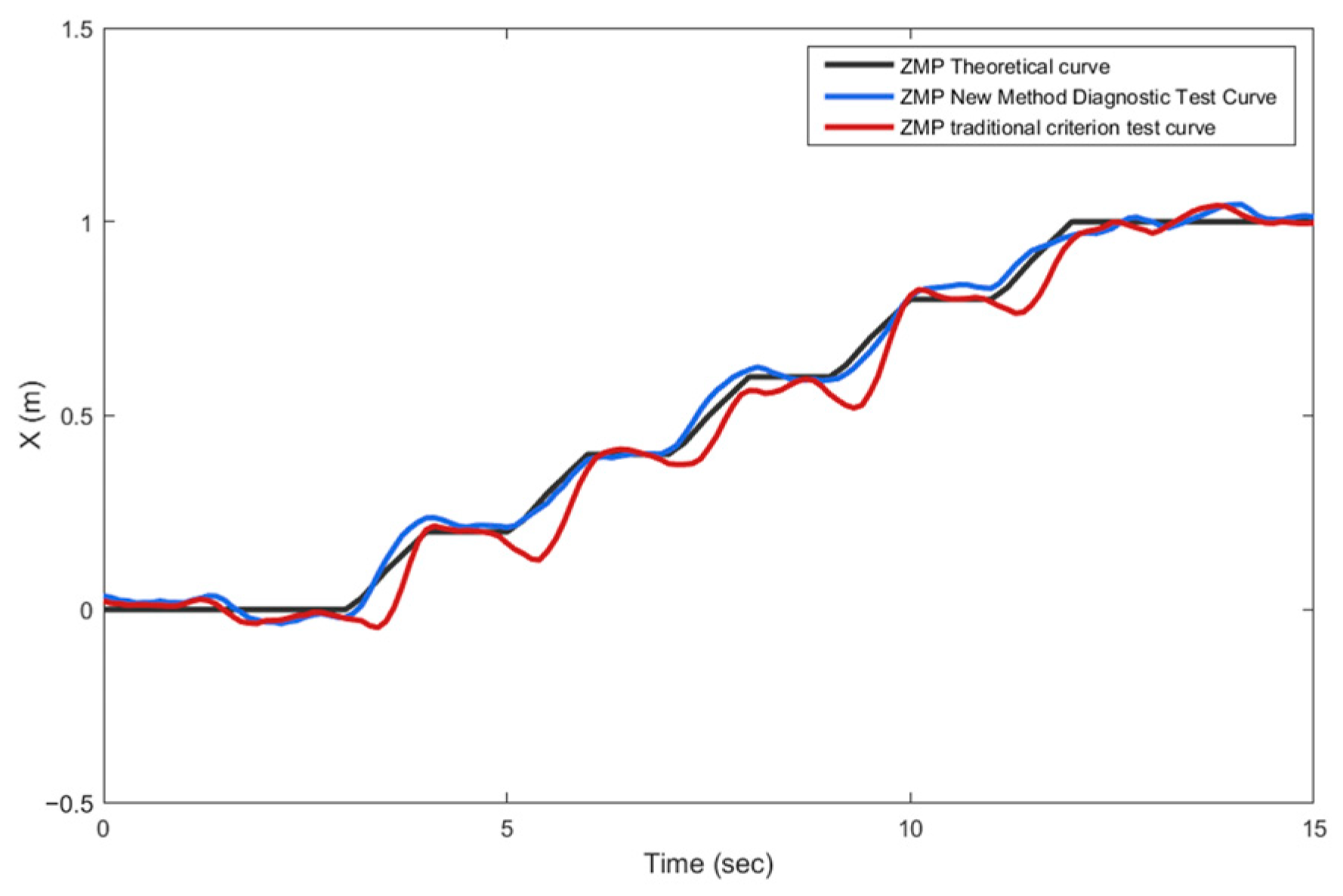

- Gait planning based on the zero-moment point (ZMP) stability criterion ensures stable locomotion by maintaining the ZMP within a predefined stability region throughout the gait cycle. Grounded in the ZMP and center of gravity (COG) stability theory, the COG trajectory is derived from a predefined ZMP trajectory. For instance, Reference [11] presents an extension of an offline ZMP-based gait planning methodology. This approach generates optimal gait trajectories by pre-planning hip and ankle joint trajectories and integrating optimization algorithms such as particle swarm optimization (PSO) and genetic algorithms (GAs) [12]. Computer-aided optimization is employed to determine the center-of-mass position, thereby facilitating ZMP stability evaluation and a quantitative analysis of the stability margin within the planning framework. Finally, the specific joint angles for the gait configuration are computed using inverse kinematics.

- (4)

- In gait planning methods based on learning, a critical aspect is the accurate recognition of human movement intent through human–robot interaction, which enables real-time gait adaptation and planning within the coupled human–robot system. For example, Reference [13] introduced a method based on an adaptive Hopf oscillator, which integrates kinematic parameters from the hip and knee joints during human gait cycles and learns adaptive oscillator parameters to convert these inputs into drive signals for joint motion control. Similarly, deep learning approaches have shown considerable promise for gait planning applications. In Reference [14], hip and knee joint data serve as training samples. Predefined joint motion signals—including angles, angular velocities, and accelerations that reflect movement intent—are fed into a pre-trained LSTM network to generate gait trajectories. This process facilitates adaptive gait planning for the lower limbs through control of the hip and knee joints. Meanwhile, Reference [15] utilizes center-of-mass trajectory data to optimize patient-specific gait parameters. In another approach, Reference [16] analyzes human–robot interaction (HRI) forces during gait and employs Gaussian process (GP) regression to model the HRI dynamics. The continuous monitoring of these interaction forces throughout the gait cycle allows for real-time torque compensation, thereby facilitating online gait planning for the exoskeleton system.

- (1)

- To address dynamic instability caused by disturbances during walking, this paper analyzes the limitations of traditional Zero-Moment Point (ZMP) criteria, particularly during the late single-leg support phase, and proposes a novel stability criterion based on the swing projection polygon to effectively evaluate stability in this critical gait phase.

- (2)

- To enhance gait stability and smoothness, this paper introduces a recurrent gait planning approach based on Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural networks. This method overcomes the non-intuitive and discontinuous nature of existing ZMP-based planning, and its feasibility and correctness are validated by incorporating the periodic characteristics of human gait.

2. Dynamic Stability Mechanism Analysis of Lower Limb Rehabilitation Robots

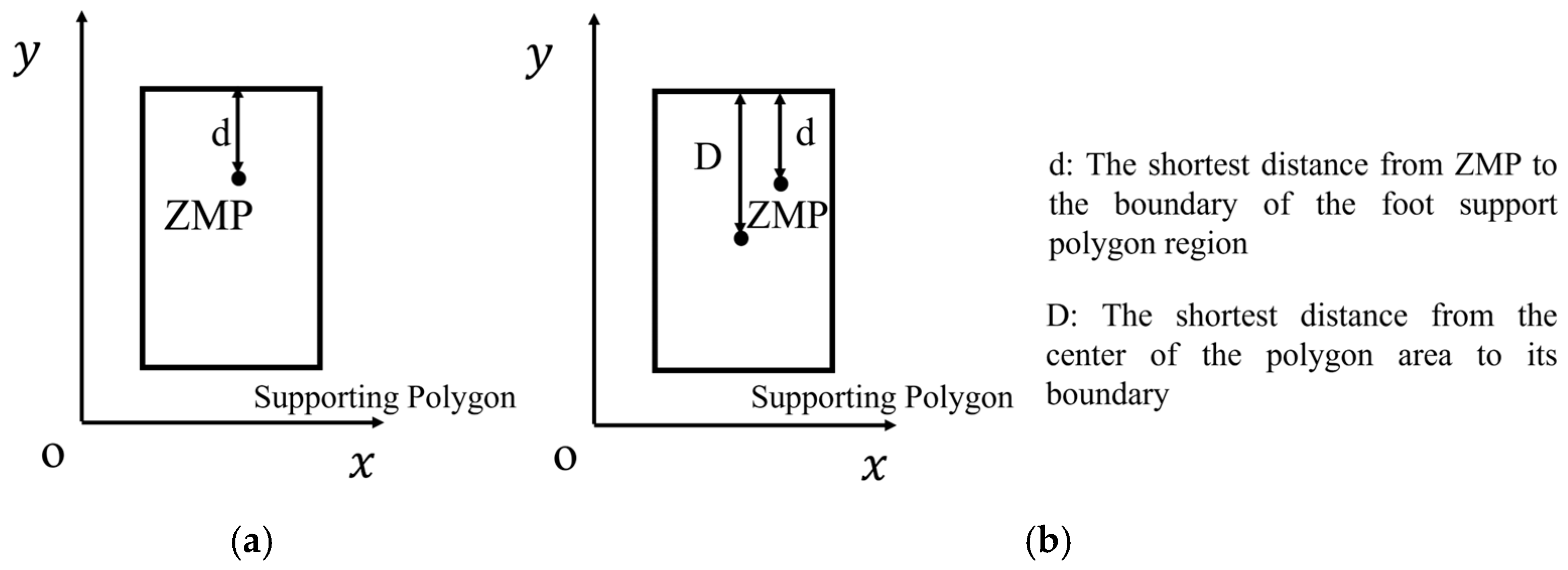

2.1. ZMP Stability Criterion Method

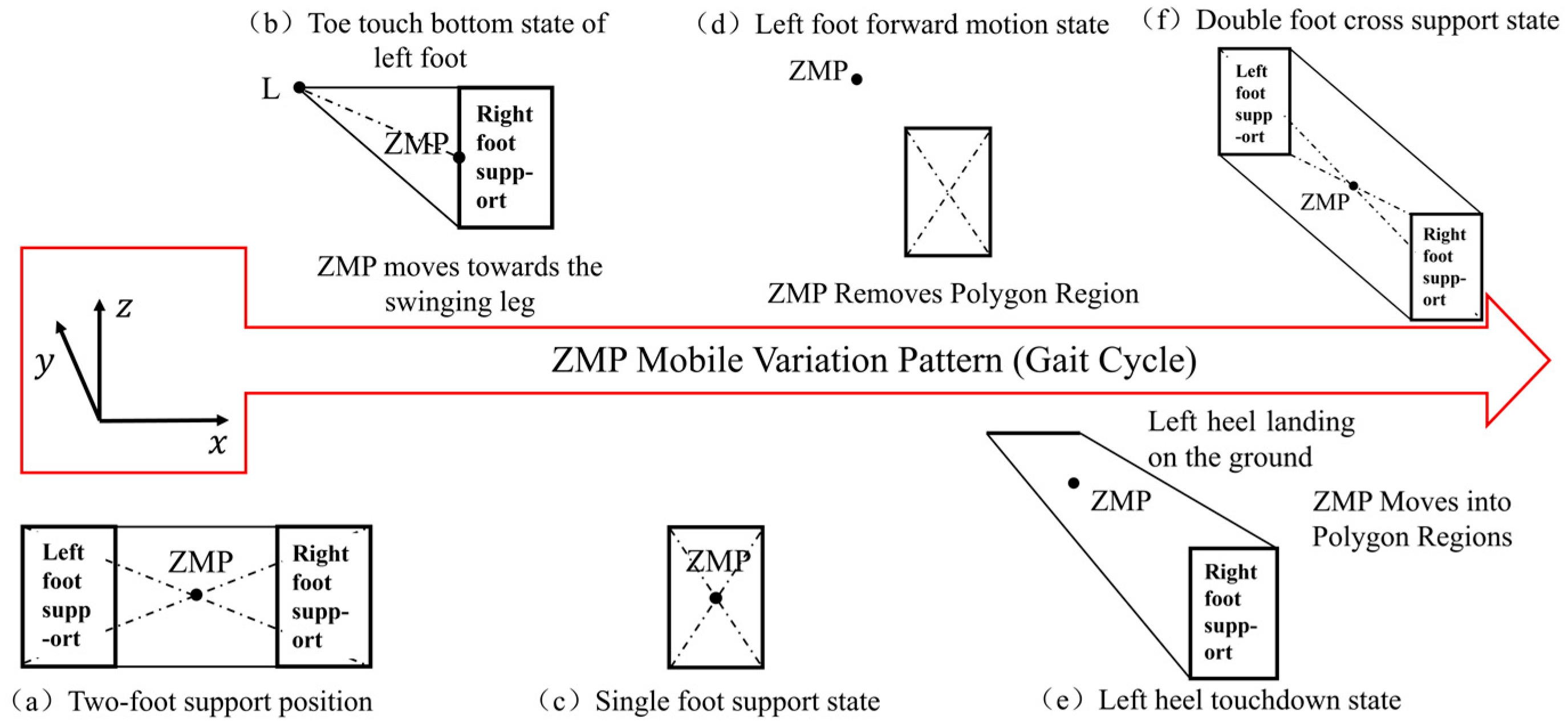

2.2. Analysis of Stability Criteria for Single-Leg Supported Oscillating Projected Polygons Based on ZMP Method

2.3. Research on Stability Criteria for Single-Leg Supported Oscillating Projected Polygons Based on ZMP

- : X coordinate of zero moment point ZMP;

- : X coordinate of the COR of the stable polygon;

- : Y coordinate of zero moment point ZMP;

- : Y coordinate of the COR of the stable polygon;

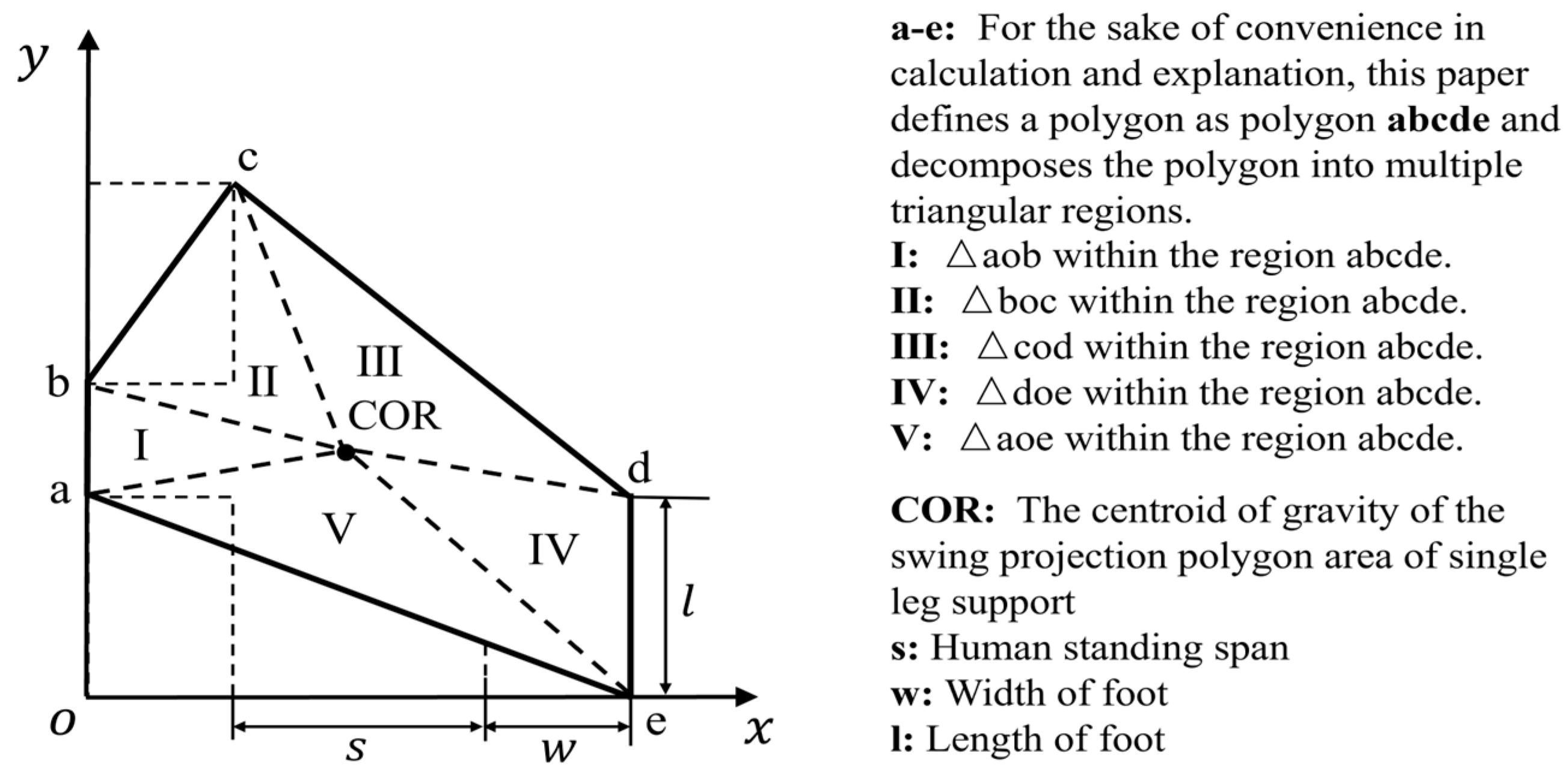

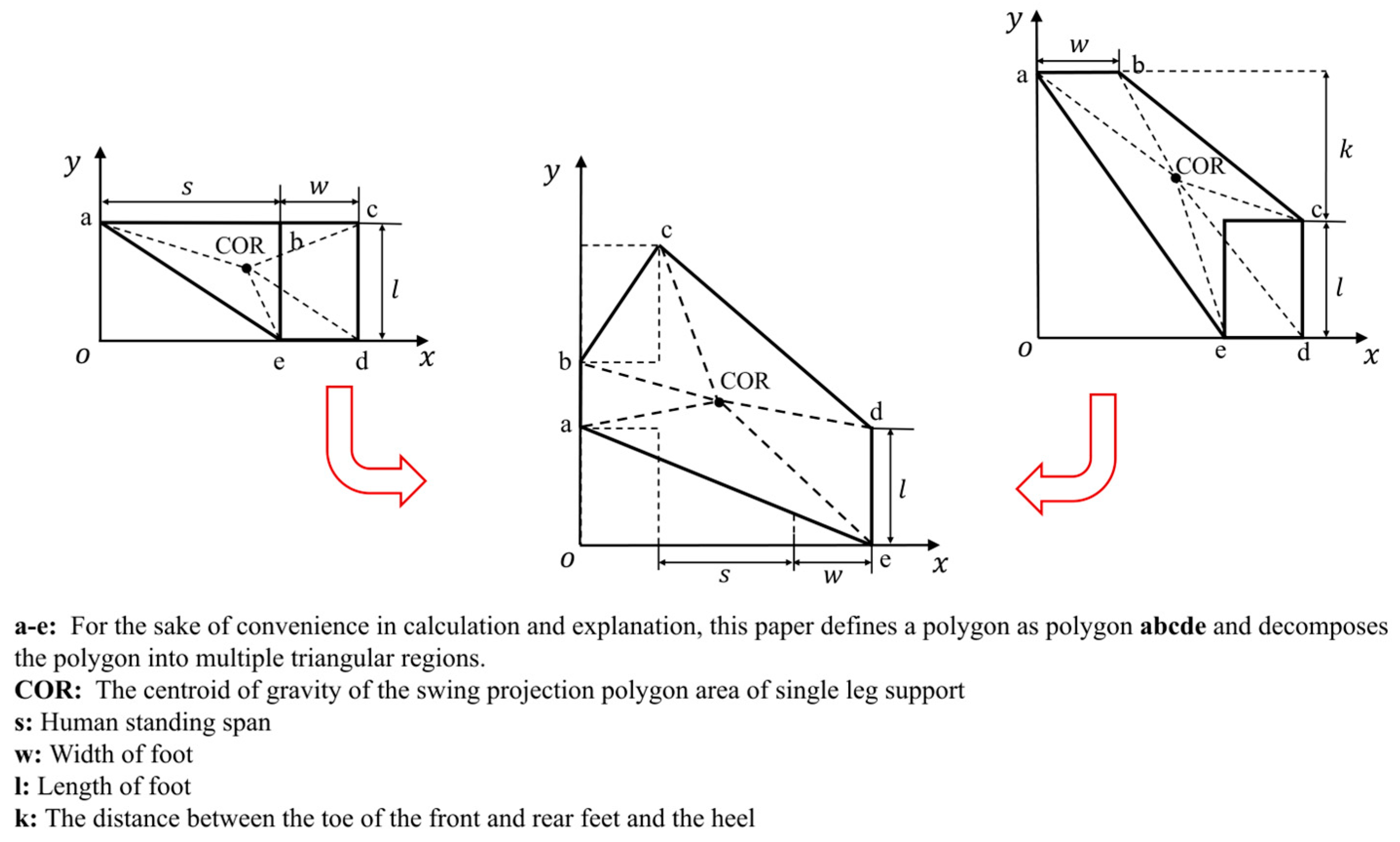

2.4. Analysis and Research on Stability Criteria Methods for Single-Leg Support Oscillating Projected Polygons

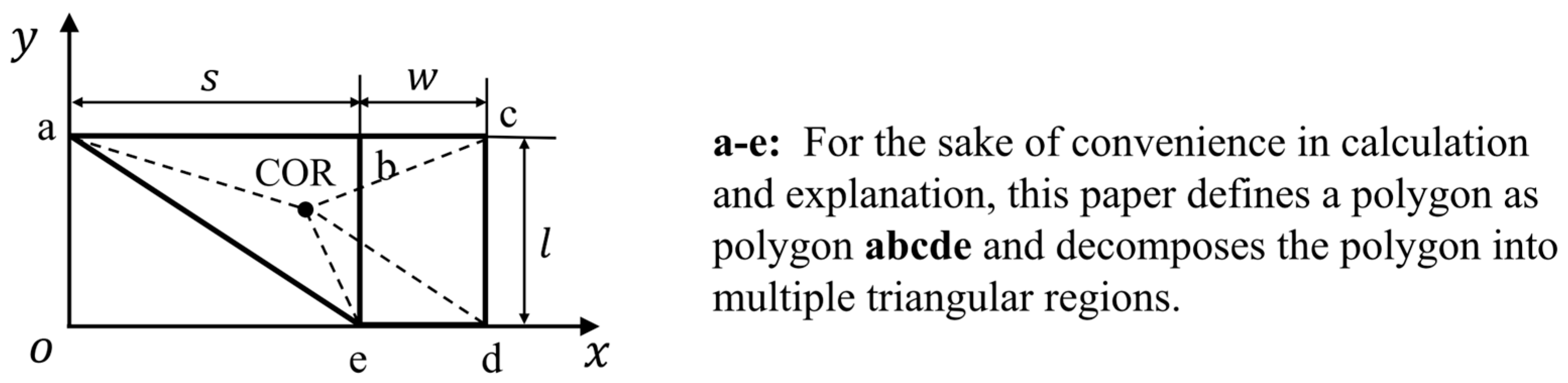

- where , , , , and are the coordinate values of points a, b, c, d, and e in Figure 4, respectively.

- Region I

- 2.

- Region Ⅱ

- 3.

- Region Ⅲ

- 4.

- Region Ⅳ

- 5.

- Region Ⅴ

- ➀

- Region

- ➁

- Region

3. ZMP-Based Stable Gait Planning Method

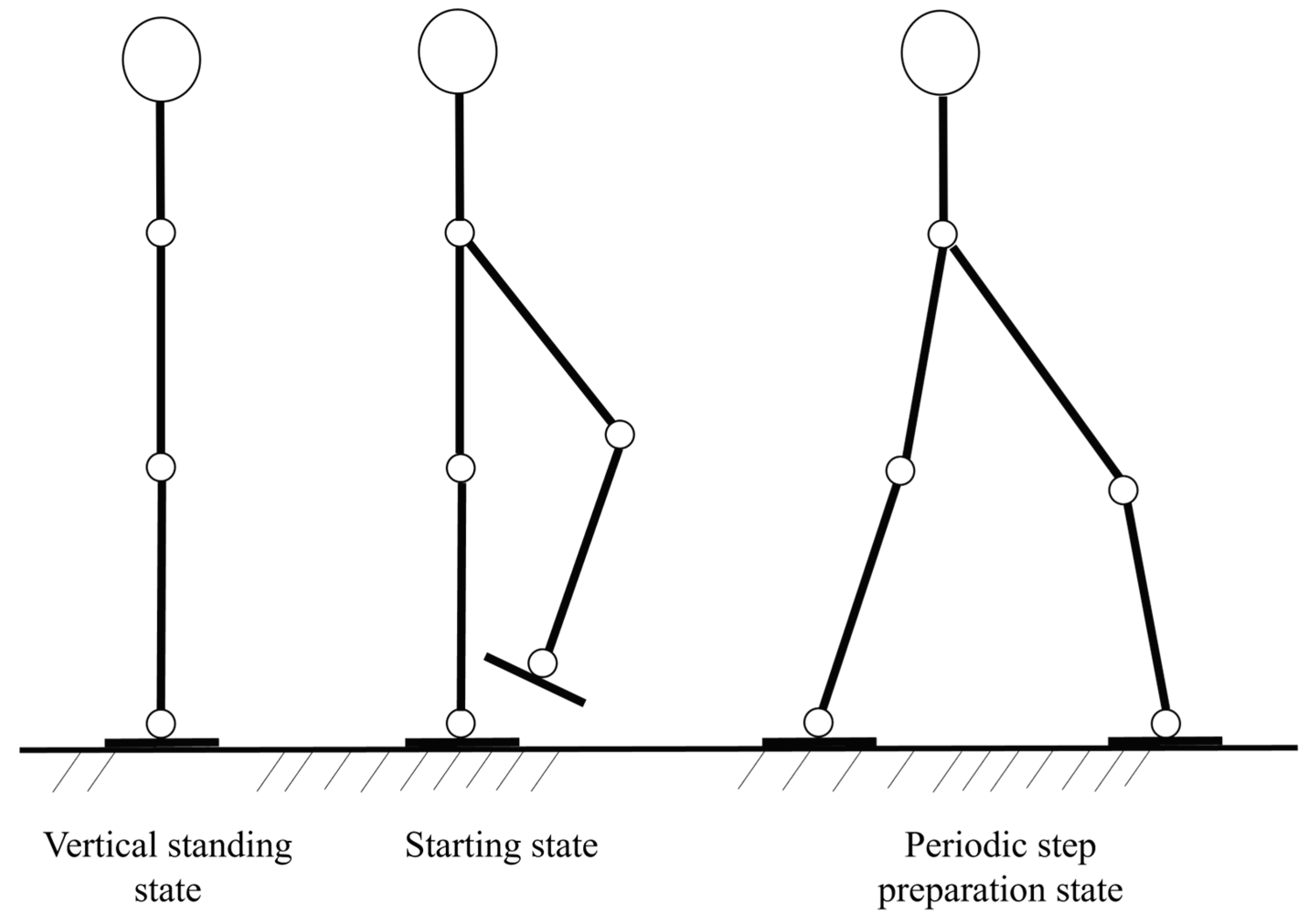

3.1. Gait Planning Method Based on Geometric Constraints

3.2. ZMP Stable Gait Planning Method Based on Whale Optimization Algorithm

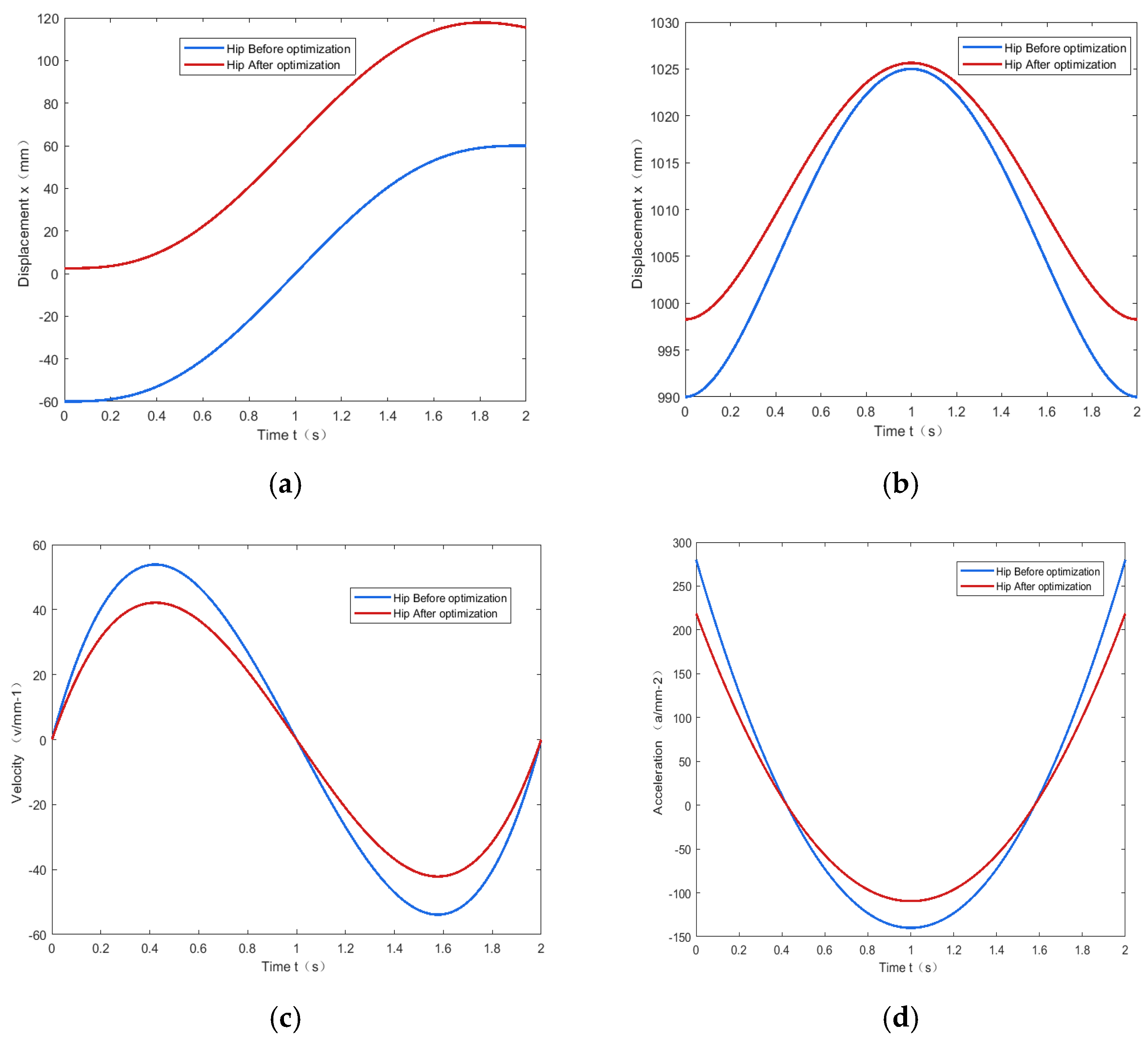

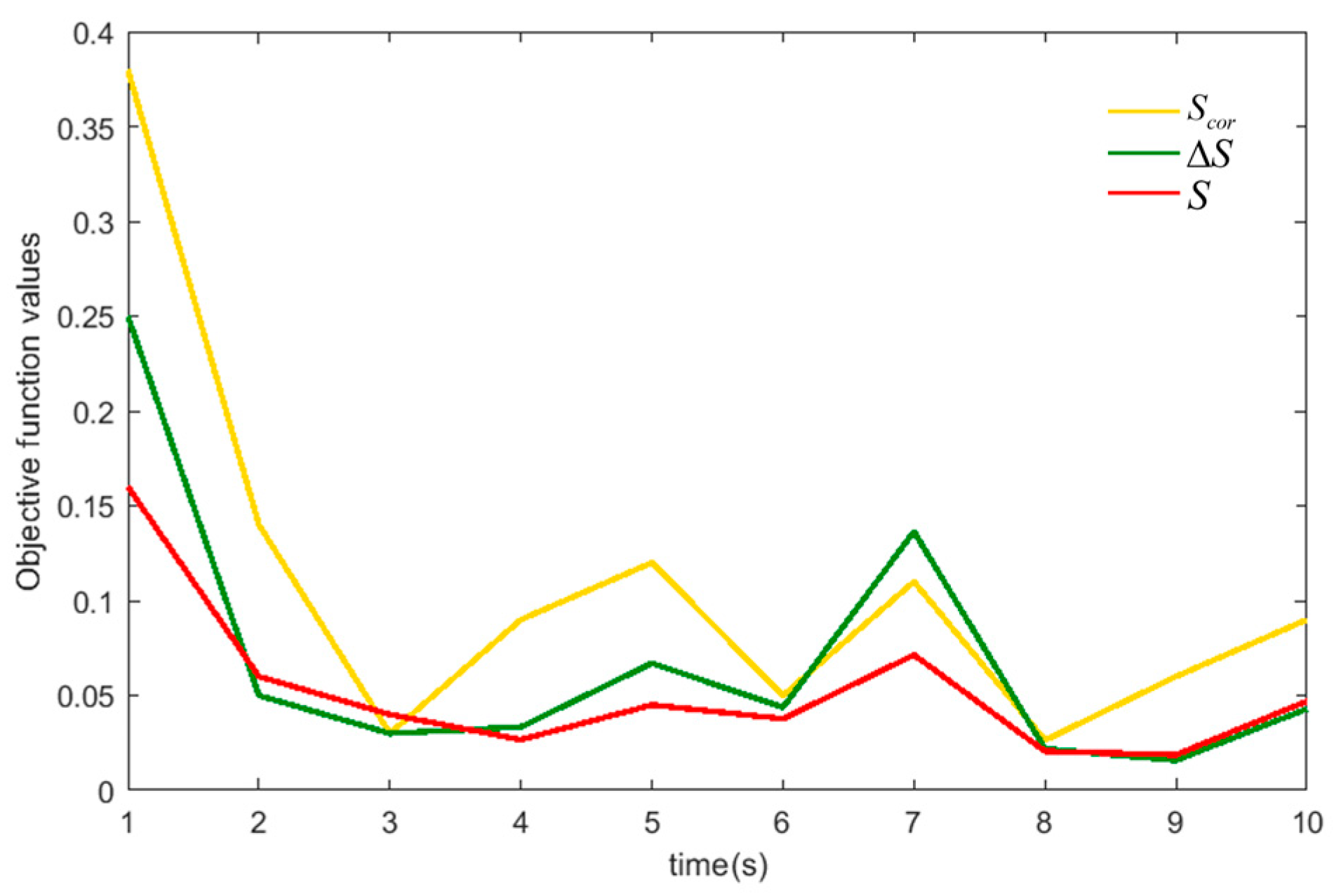

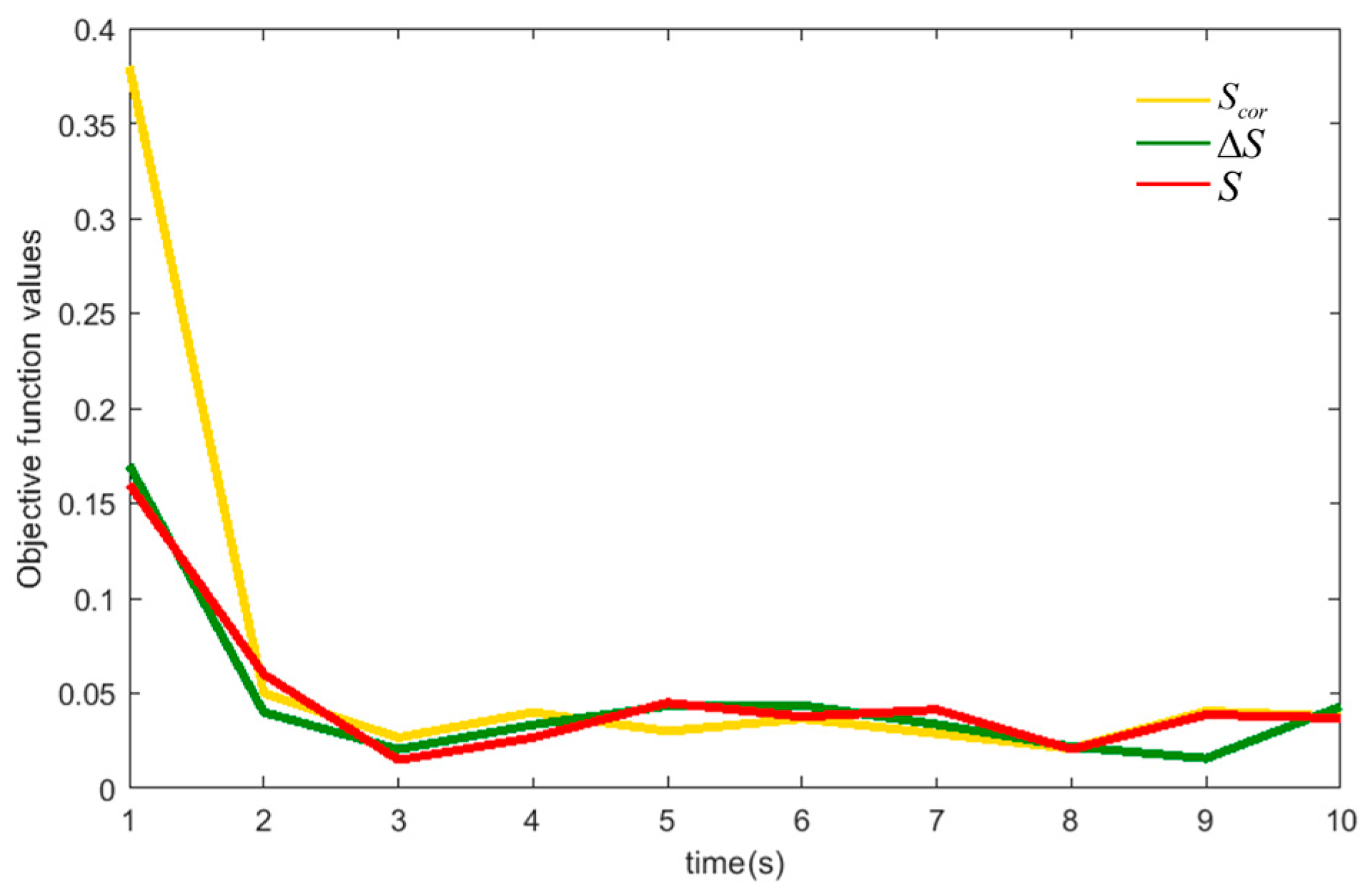

Gait Parameter Optimization

3.3. Analysis of Gait Planning Parameter Optimization Results

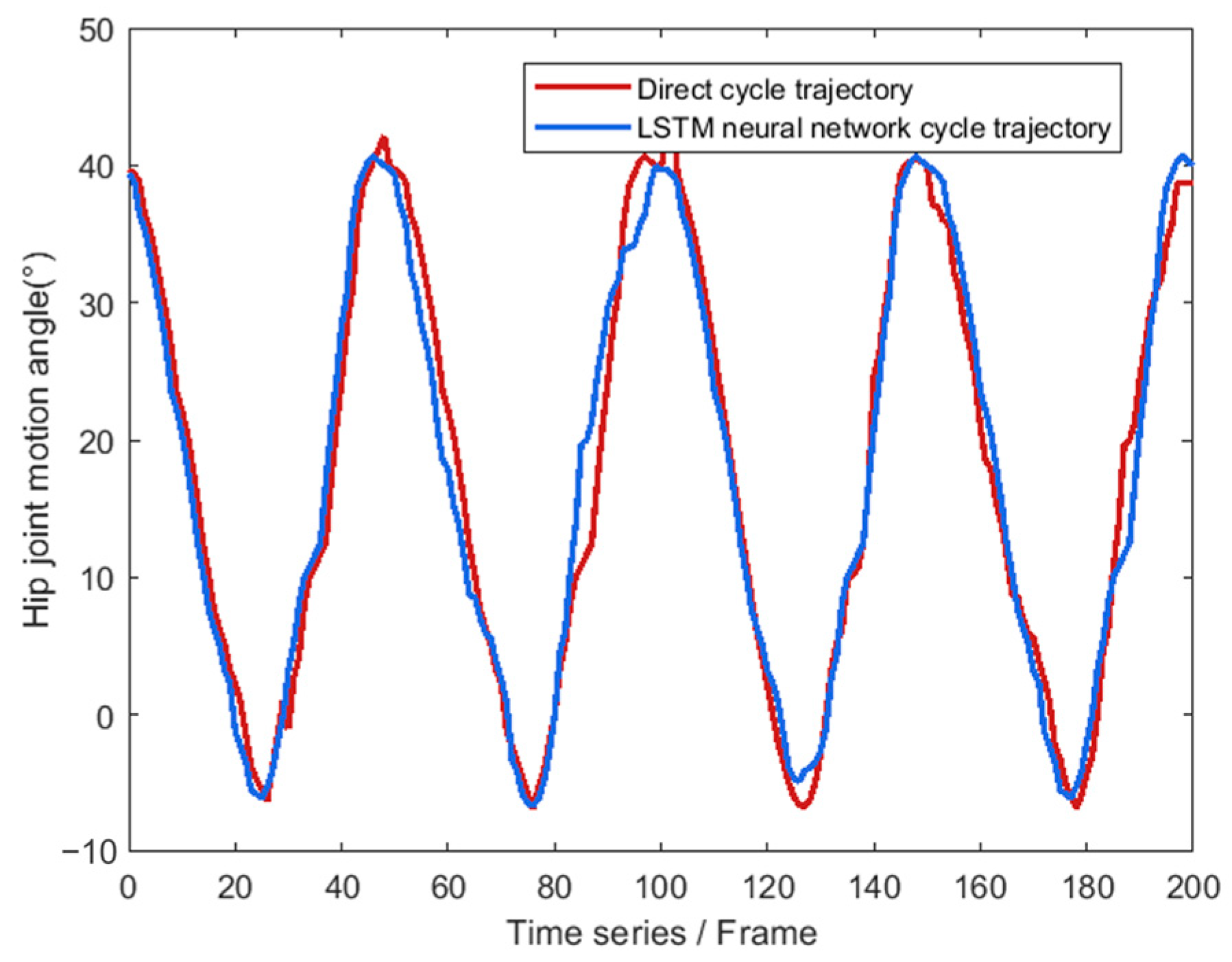

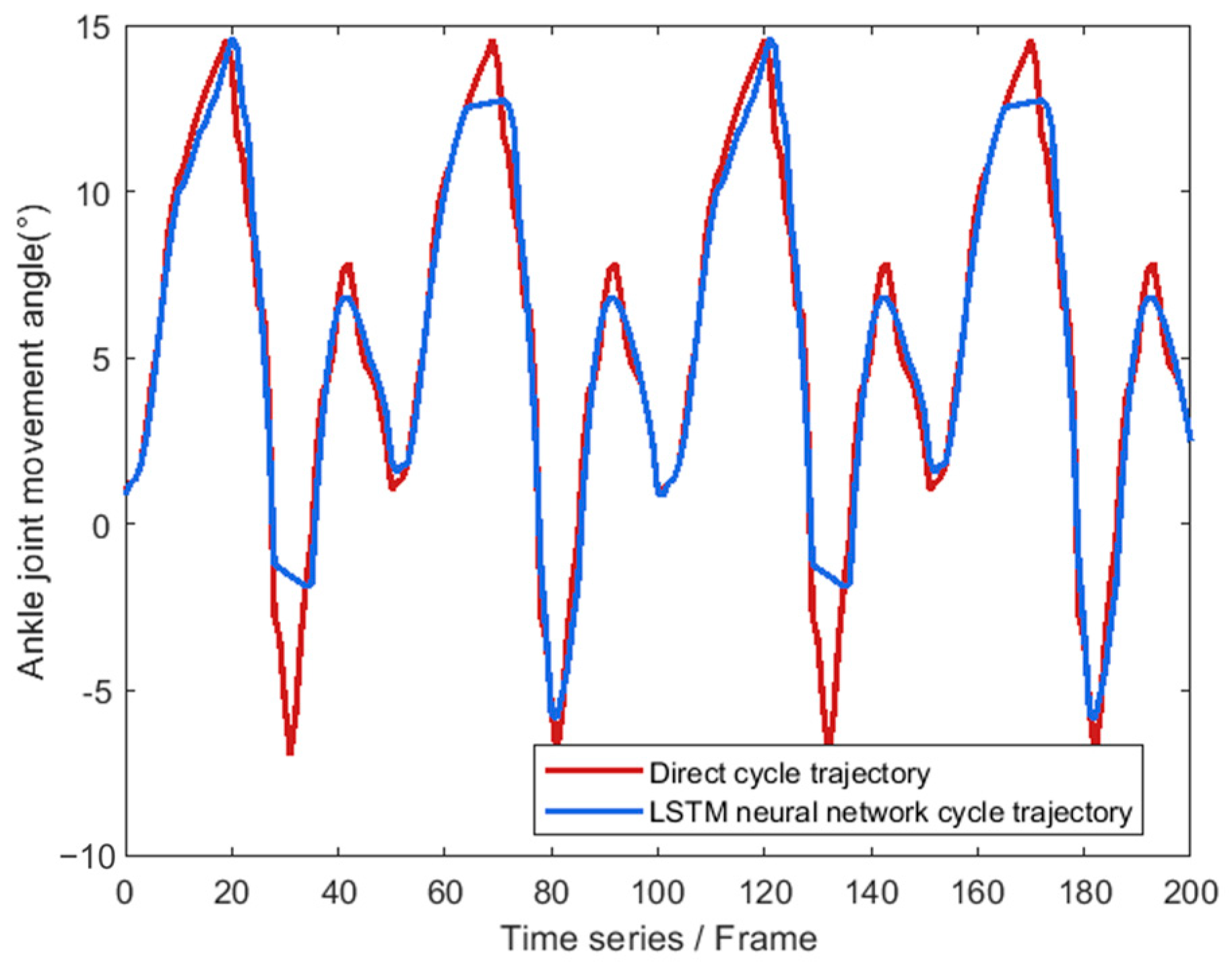

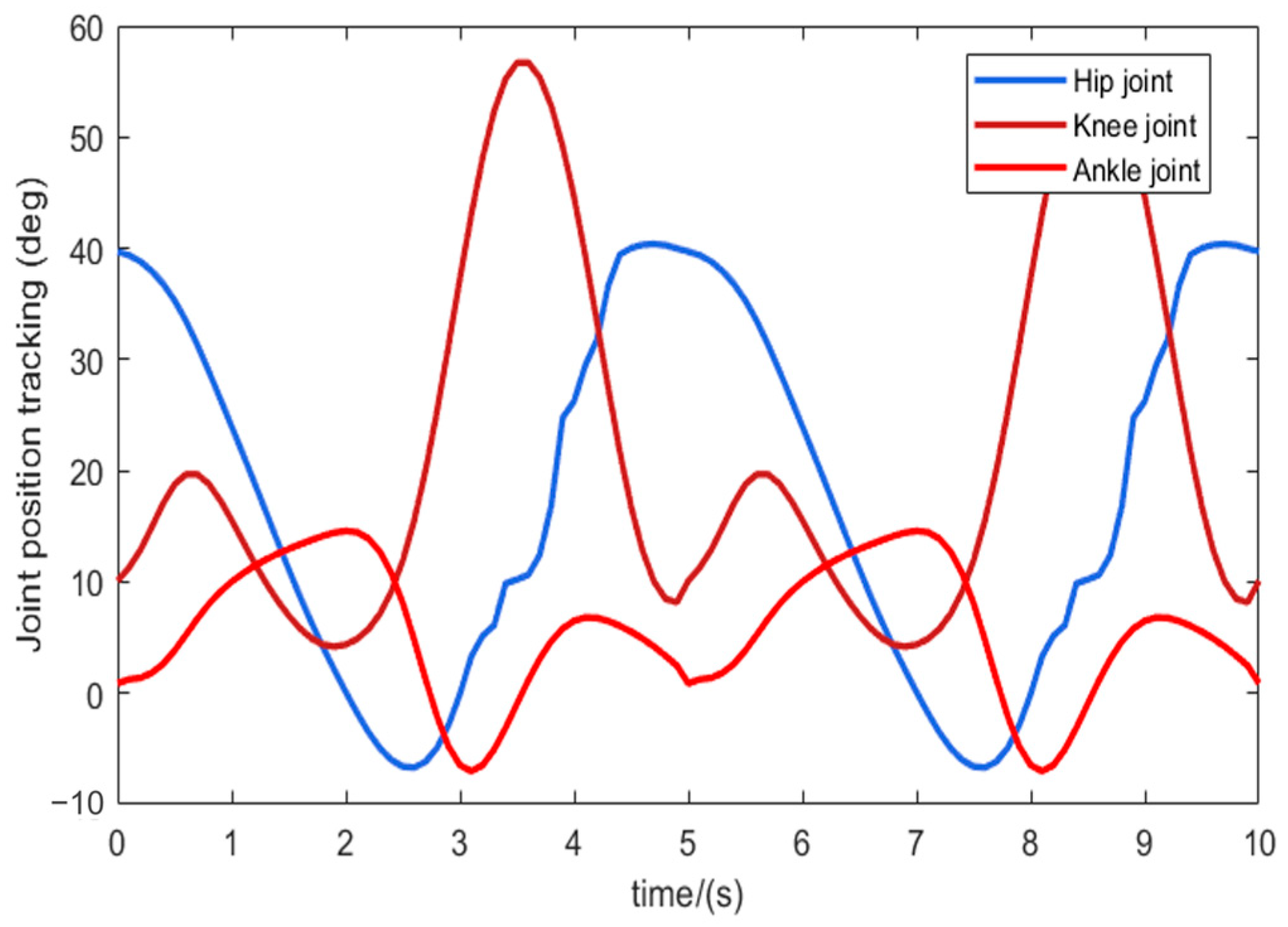

4. Cycle Gait Generation Method of Lower Limb Exoskeleton Rehabilitation Robot Based on LSTM Neural Network

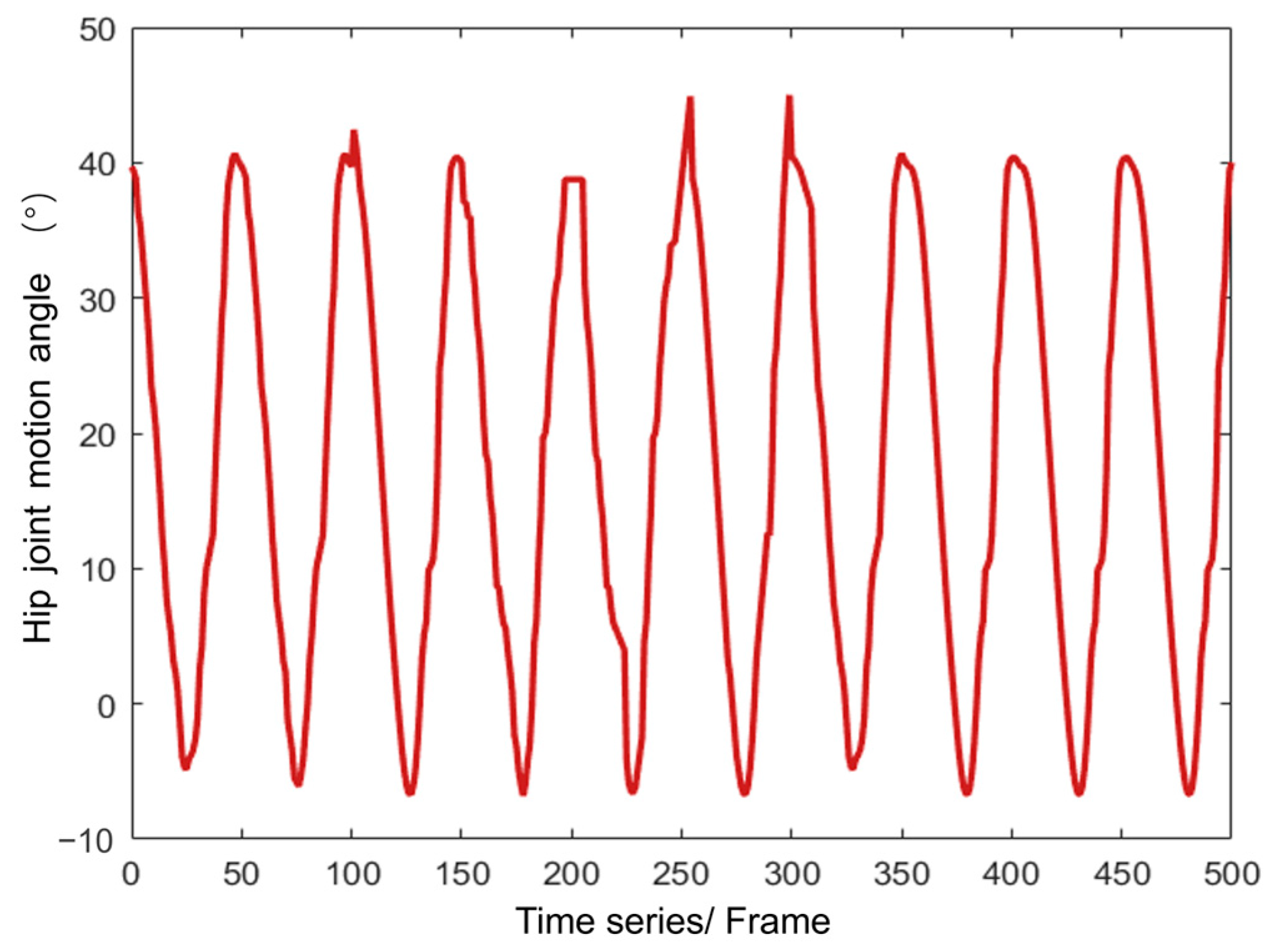

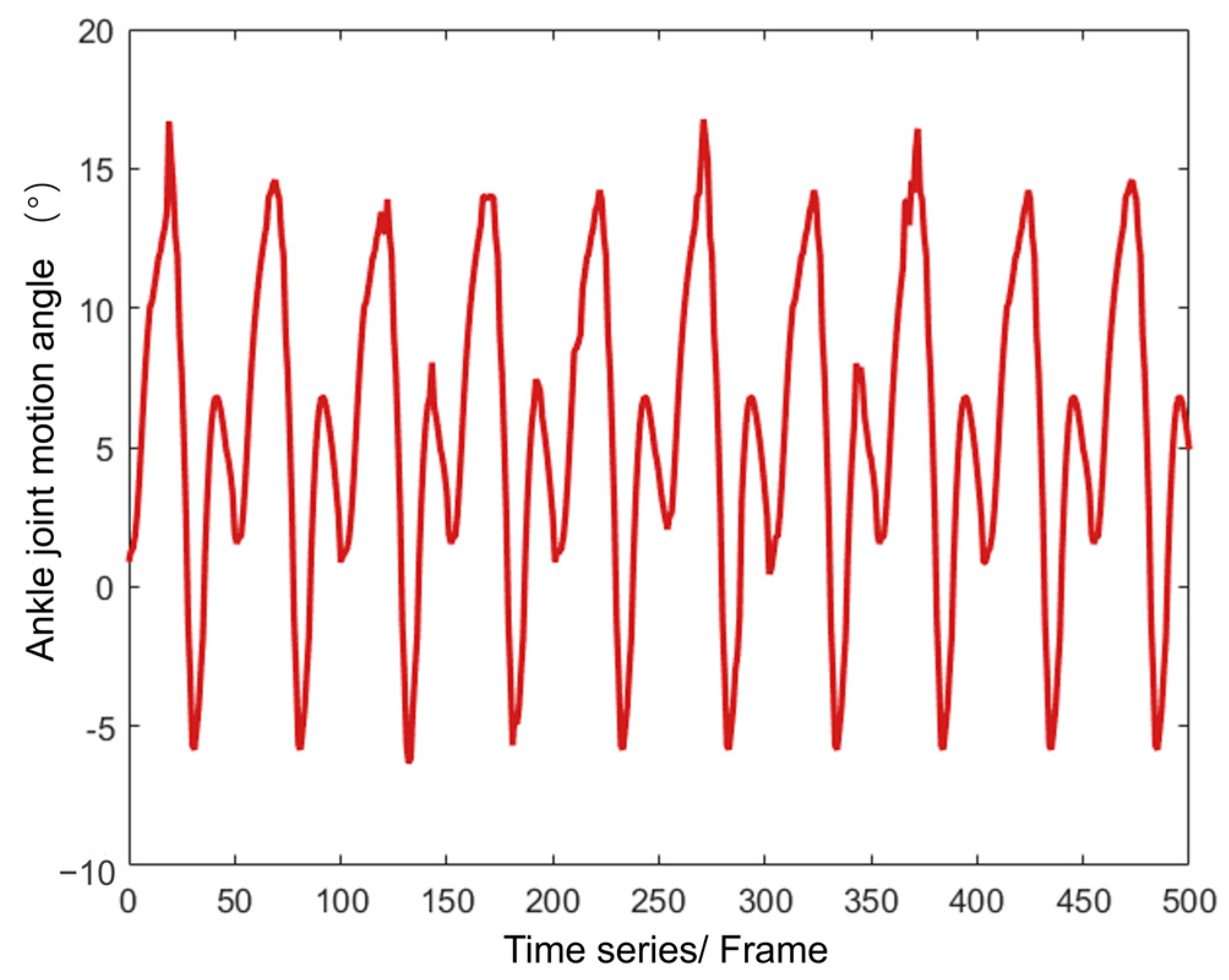

4.1. Construction of the Sample Set for the Cyclic Gait Prediction Model

4.2. Data Preprocessing for Lower Limb Exoskeleton Rehabilitation Robots Based on Phase Space Reconstruction

- , joint angle sequence length;

- , the number of state points in the reconstructed phase space;

- : the number of subsequences;

- : Sequence label.

4.3. Establishment of a Joint Angle Sequence Prediction Model for Walking Motion in Lower-Limb Exoskeleton Robots

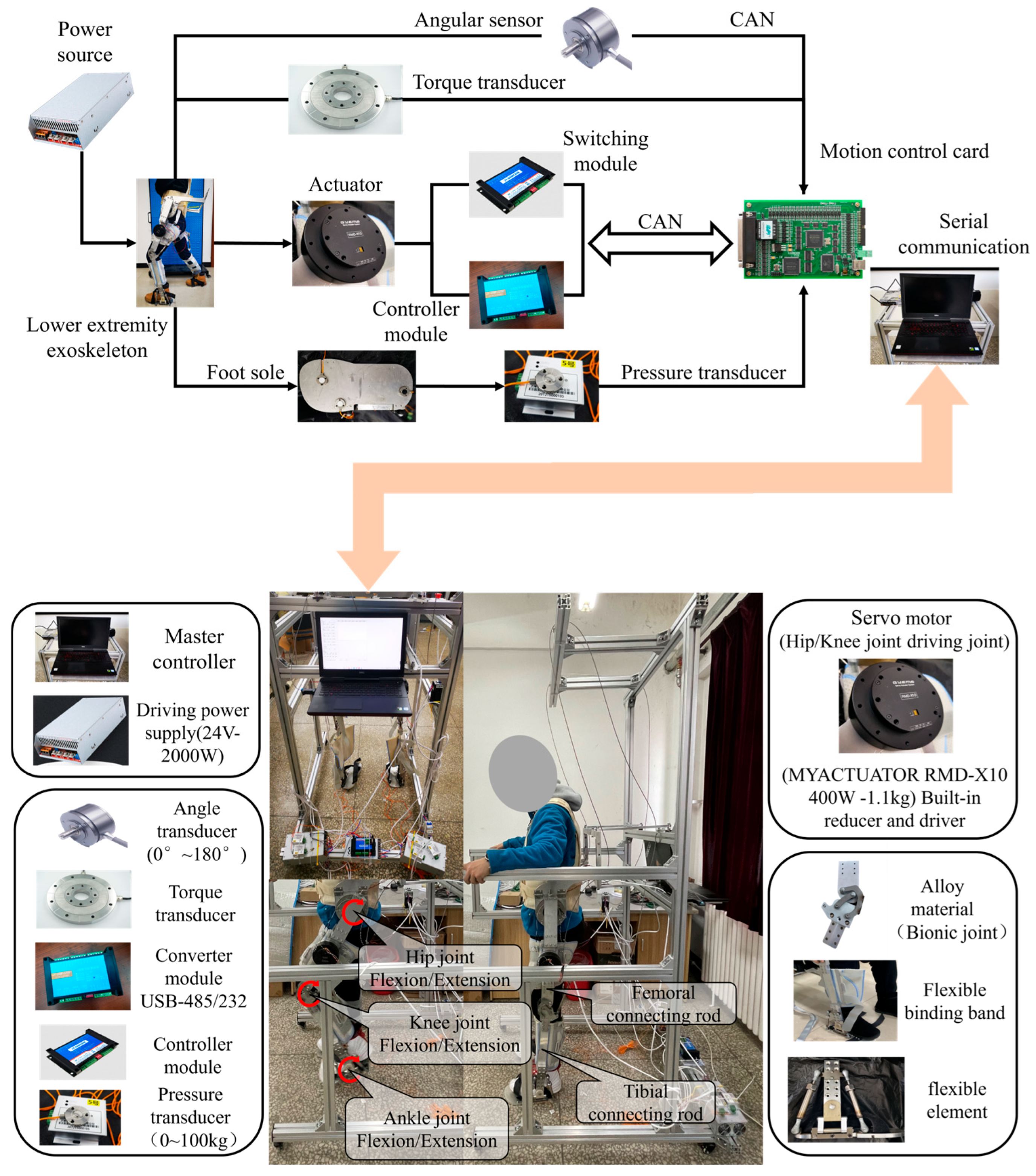

5. Experimental Analysis of Lower Limb Exoskeleton Rehabilitation Robots

5.1. Hardware System Design for Lower Limb Exoskeleton Rehabilitation Robot

5.1.1. Drive System Design

5.1.2. Auxiliary System Design

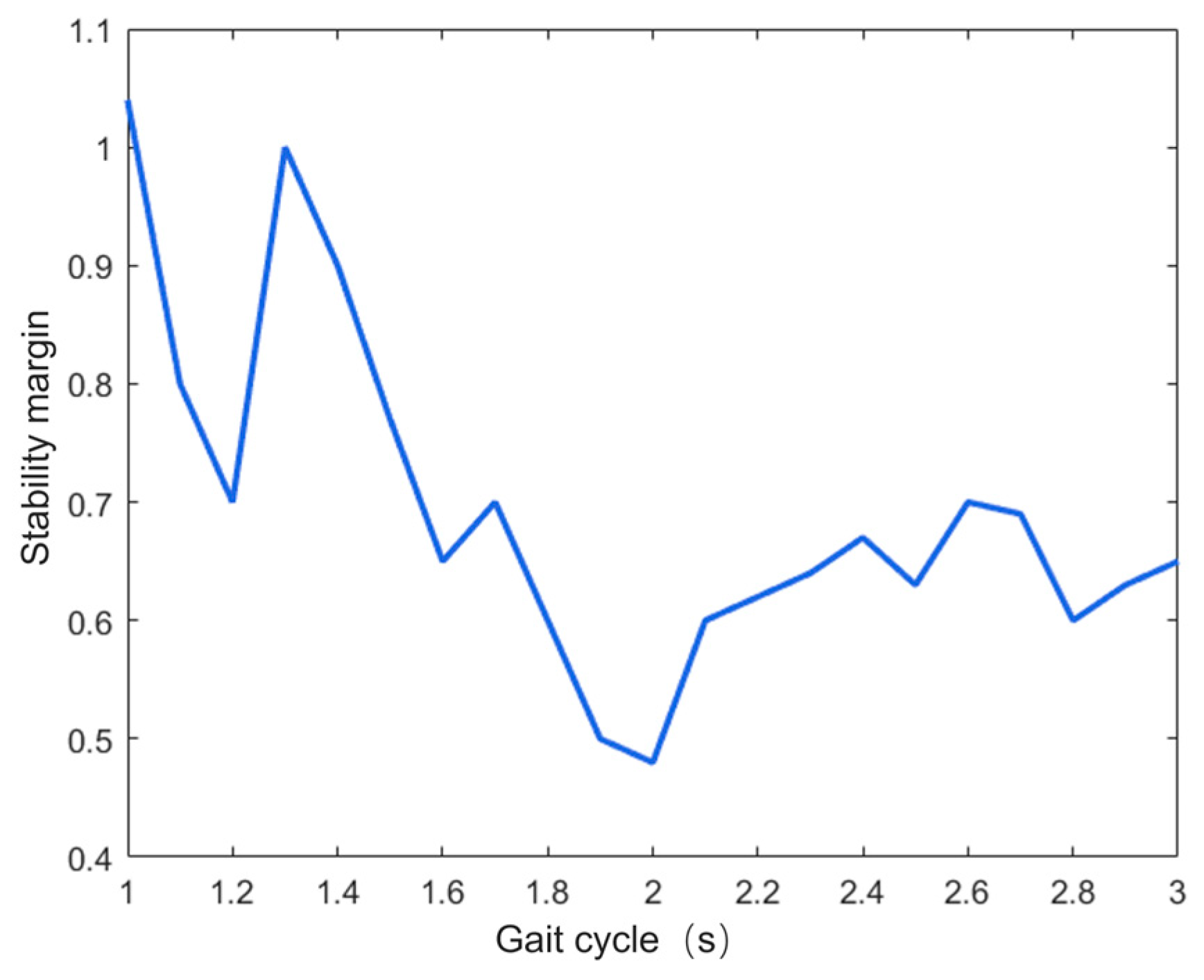

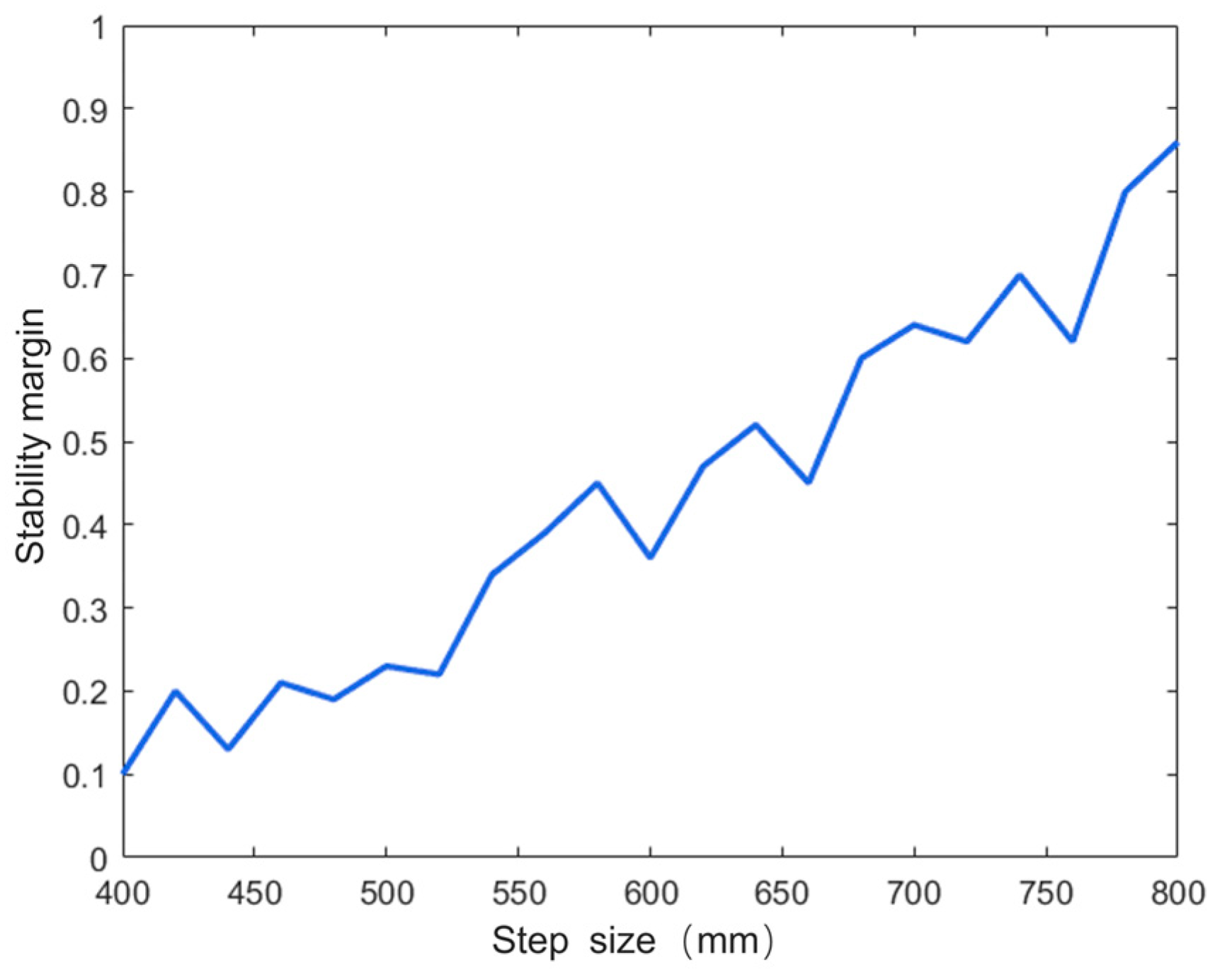

5.2. Study on Factors Affecting the Dynamic Stability of Lower-Limb Exoskeleton Rehabilitation Robots

5.2.1. The Influence of Gait Cycle on Dynamic Stability

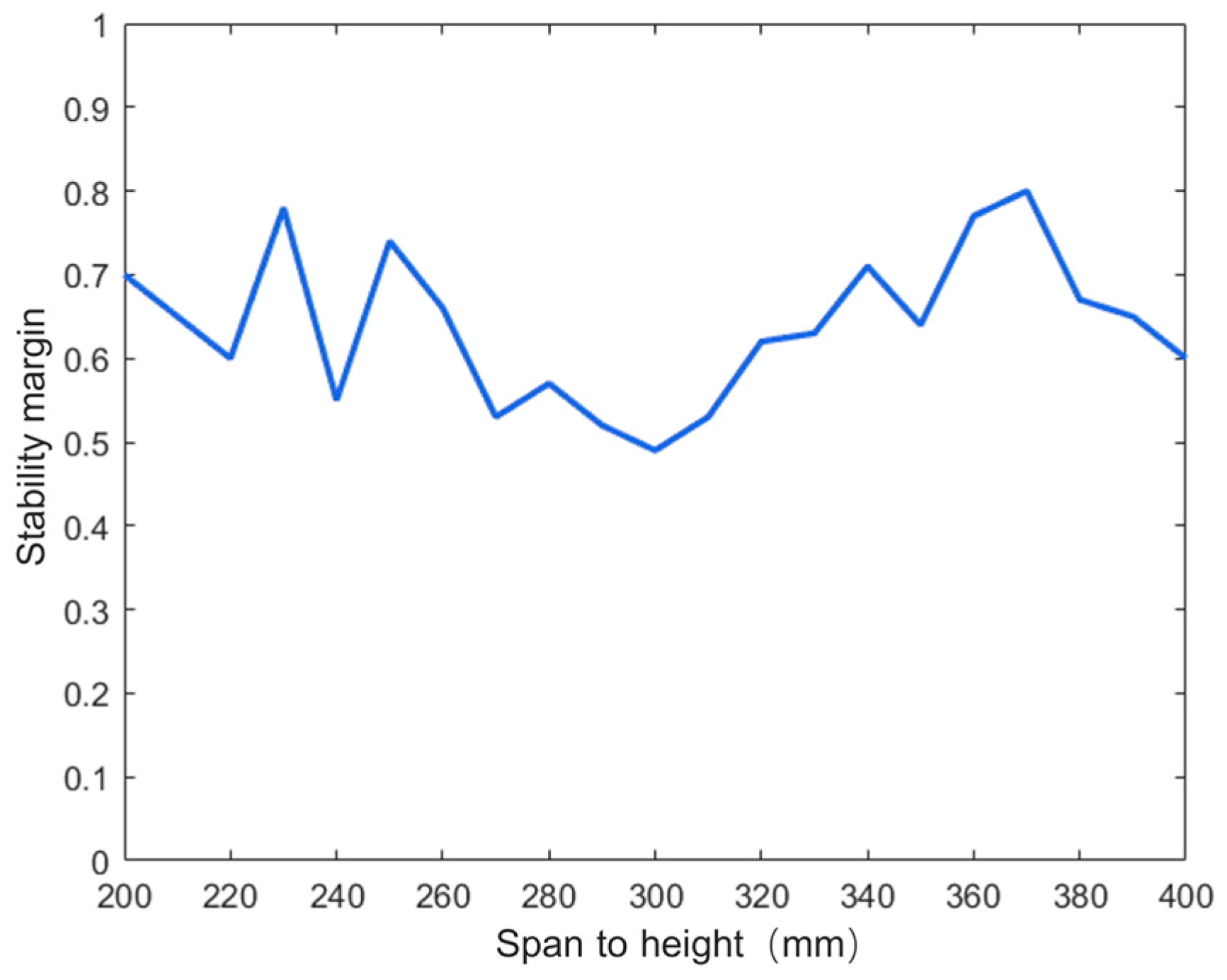

5.2.2. The Effect of Step Length on Dynamic Stability

5.2.3. The Effect of Clearance Height on Dynamic Stability

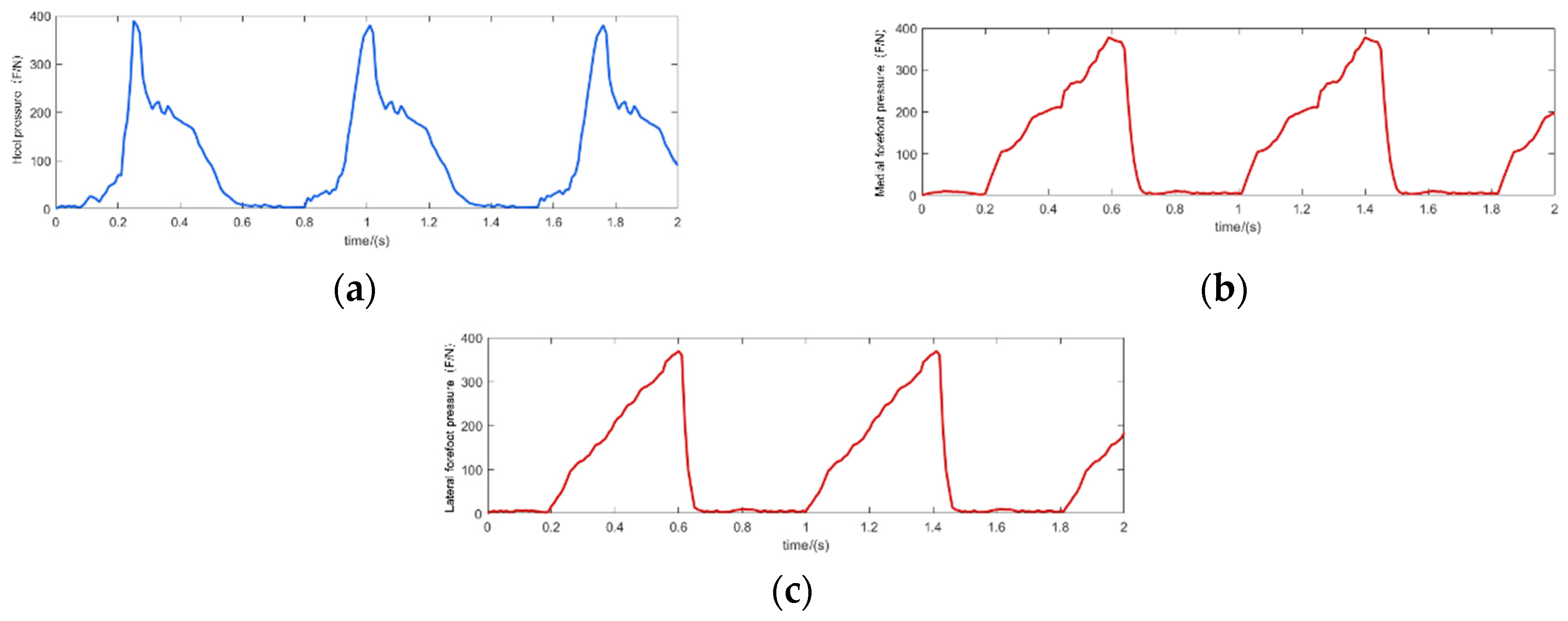

5.3. Experimental Analysis of Dynamic Stability Characteristics of Walking Posture

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, F.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Tan, M.; Yu, J. Adaptive Gait Training of a Lower Limb Rehabilitation Robot Based on Human–Robot Interaction Force Measurement. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2024, 5, 0115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Sun, Y.; Song, R.; Wei, Z. Dynamic movement primitives modulation-based compliance control for a new sitting/lying lower limb rehabilitation robot. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 44125–44134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Peng, H.; Zheng, M.; Wei, Z.; Fan, T.; Song, R. Trajectory deformation-based multi-modal adaptive compliance control for a wearable lower limb rehabilitation robot. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2024, 32, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, P.; Fang, D. Research on the Influence of Exoskeletons on Human Characteristics by Modeling and Simulation Using the AnyBody Modeling System. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, D.; Yu, H.; Cheng, B.; Niu, J. A multistage hemiplegic lower-limb rehabilitation robot: Design and gait trajectory planning. Sensors 2024, 24, 2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallery, H.; Van Asseldonk, E.H.; Buss, M.; Van Der Kooij, H. Reference trajectory generation for rehabilitation robots: Complementary limb motion estimation. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2008, 17, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfister, A.; West, A.M.; Bronner, S.; Noah, J.A. Comparative abilities of Microsoft Kinect and Vicon 3D motion capture for gait analysis. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 2014, 38, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Su, C.; Huang, L.; Huang, S.; Xie, L. Personalized passive training control strategy for a lower limb rehabilitation robot with specified step lengths. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2025, 18, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajita, S.; Kanehiro, F.; Kaneko, K.; Yokoi, K.; Hirukawa, H. The 3D linear inverted pendulum mode: A simple modeling for a biped walking pattern generation. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. Expanding the Societal Role of Robotics in the Next Millennium, Maui, HI, USA, 29 October–3 November 2001; IEEE: New York, NJ, USA, 2001; Volume 1, pp. 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Sczesny-Kaiser, M.; Höffken, O.; Aach, M.; Cruciger, O.; Grasmücke, D.; Meindl, R.; Schildhauer, T.; Schwenkreis, P.; Tegenthoff, M. HAL® exoskeleton training improves walking parameters and normalizes cortical excitability in primary somatosensory cortex in spinal cord injury patients. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2015, 12, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiwaki, K.; Kagami, S. Simultaneous planning of CoM and ZMP based on the preview control method for online walking control. In Proceedings of the 11th IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots, Bled, Slovenia, 26–28 October 2011; IEEE: New York, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 745–751. [Google Scholar]

- Jafar, K.; Sadjaad, O. Real-time walking pattern generation for a lower limb exoskeleton, implemented on the Exposed robot. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2019, 116, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Cheng, H.; Yue, C.; Huang, R.; Guo, H. Dynamic Balance Gait for Walking Assistance Exoskeleton. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 2018, 2018, 7847014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santacruz, C.; Nakamura, Y. Walking motion generation of humanoid robots: Connection of orbital energy trajectories via minimal energy control. In Proceedings of the IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots, Bled, Slovenia, 26–28 October 2011; IEEE: New York, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 695–700. [Google Scholar]

- Duschau-Wicke, A.; Caprez, A.; Riener, R. Patient-cooperative Control Increases Active Participation of Individuals with SCI During Robot-aided Gait Training. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2010, 7, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A.; Vreede, K.S.; Häglund, V.; Kawamoto, H.; Sankai, Y.; Borg, J. Gait Training Early after Stroke with a New Exoskeleton–the Hybrid Assistive Limb: A Study of Safety and Feasibility. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2014, 11, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Wang, Z.; Pang, Z.; Sun, J.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, H. Electrically driven lower limb exoskeleton rehabilitation robot based on anthropomorphic design. Machines 2022, 10, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlalolini, D.; Chevallereau, C.; Aoustin, Y. Comparison of different gaits with rotation of the feet for a planar biped. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2009, 57, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. Analysis and experimental research on stability characteristics of squatting posture of wearable lower limb exoskeleton robot. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 125, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, N.; Hasan, S.; Mashud, G.A.; Bhujel, S. Neural Network for Enhancing Robot-Assisted Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. Actuators 2025, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Ai, Q.; Meng, W.; Liu, Q.; Xie, S.Q. Individualized gait trajectory prediction based on fusion LSTM networks for robotic rehabilitation training. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (AIM), Delft, The Netherlands, 12–16 July 2021; IEEE: New York, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 988–993. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Jiang, H.; Gao, M.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Pang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jiao, Y. Research on Iterative Learning Method for Lower Limb Exoskeleton Rehabilitation Robot Based on RBF Neural Network. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Jiao, W. Control Method of Lower Limb Rehabilitation Robot Based on Nonlinear Time Series Prediction Model and Sensor Technology. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 152532–152543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Dong, J.; Teng, R.; Liu, P.; Yue, X.; Zhang, X. A Hierarchical Distributed Control System Design for Lower Limb Rehabilitation Robot. Technologies 2025, 13, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leerskov, K.S.; Spaich, E.G.; Jochumsen, M.R.; Andreasen Struijk, L.N.S. Design and Demonstration of a Hybrid FES-BCI-Based Robotic Neurorehabilitation System for Lower Limbs. Sensors 2025, 25, 4571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Zhou, L. Kinematic analysis and dynamic optimization simulation of a novel unpowered exoskeleton with parallel topology. J. Robot. 2019, 2019, 2953830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Du, Y.; Sun, X.; Lin, J. Study of humanoid robot gait based on human walking captured data. In Proceedings of the 2015 34th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Hangzhou, China, 28–30 July 2015; IEEE: New York, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 4480–4485. [Google Scholar]

| Number of Network Layers and Number of Neurons per Layer | Mean Square Error | |

|---|---|---|

| Hip Exoskeleton Motion Angle | Ankle Exoskeleton Motion Angle | |

| Monolayer (100 neurons) | 0.0130 | 0.0110 |

| Monolayer (200 neurons) | 0.0056 | 0.0061 |

| Monolayer (300 neurons) | 0.0045 | 0.0093 |

| Double layer (100 neurons) | 0.0090 | 0.0047 |

| Double layer (200 neurons) | 0.0021 | 0.0064 |

| Double layer (300 neurons) | 0.0024 | 0.0037 |

| Three layers (100 neurons) | 0.0045 | 0.0022 |

| Three layers (200 neurons) | 0.0033 | 0.0019 |

| Three layers (300 neurons) | 0.0011 | 0.0012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gao, M.; Yang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Ni, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhu, G.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Bu, J.; Wu, B. A Novel Stability Criterion Based on the Swing Projection Polygon for Gait Rehabilitation Exoskeletons. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010402

Gao M, Yang W, Zhong Y, Ni Y, Jiang H, Zhu G, Li J, Wang Z, Bu J, Wu B. A Novel Stability Criterion Based on the Swing Projection Polygon for Gait Rehabilitation Exoskeletons. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):402. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010402

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Moyao, Wei Yang, Yuexi Zhong, Yingxue Ni, Huimin Jiang, Guokai Zhu, Jing Li, Zhanli Wang, Jiaqi Bu, and Bo Wu. 2026. "A Novel Stability Criterion Based on the Swing Projection Polygon for Gait Rehabilitation Exoskeletons" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010402

APA StyleGao, M., Yang, W., Zhong, Y., Ni, Y., Jiang, H., Zhu, G., Li, J., Wang, Z., Bu, J., & Wu, B. (2026). A Novel Stability Criterion Based on the Swing Projection Polygon for Gait Rehabilitation Exoskeletons. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010402